#alcovasaurus

Note

you like dinos? name every dino

Aardonyx Abdarainurus Abelisaurus Abrictosaurus Abrosaurus Abydosaurus Acantholipan Acanthopholis Achelousaurus Acheroraptor Achillesaurus Achillobator Acristavus Acrocanthosaurus Acrotholus Adamantisaurus Adasaurus Adelolophus Adeopapposaurus Adratiklit Adynomosaurus Aegyptosaurus Aeolosaurus Aeolosaurus Aepyornithomimus Aerosteon Afromimus Afrovenator Agathaumas Agilisaurus Agrosaurus Agujaceratops Agujaceratops Agustinia Ahshislepelta Ajkaceratops Ajnabia Akainacephalus Alamitornis Alaskacephale Albalophosaurus Albertaceratops Albertadromeus Albertavenator Albertonykus Albertosaurus Albinykus Alcmonavis Alcovasaurus Alectrosaurus Aletopelta Algoasaurus Alioramus Alioramus Allosaurus Allosaurus Allosaurus Almas Alnashetri Altirhinus Altispinax Alvarezsaurus Alxasaurus Amanzia Amargasaurus Amargatitanis Amazonsaurus Ambiortus Ambopteryx Ampelosaurus Amphicoelias Amtocephale Amurosaurus Amygdalodon Anabisetia Analong Anasazisaurus Anchiceratops Anchiornis Anchisaurus Andesaurus Angolatitan Angulomastacator Anhuilong Aniksosaurus Animantarx Ankylosaurus Anodontosaurus Anomalipes Anoplosaurus Anserimimus Antarcticavis Antarctopelta Antarctosaurus Antarctosaurus Antarctosaurus Antarctosaurus Antetonitrus Antrodemus Anzu Aoniraptor Aorun Apatoraptor Apatornis Apatosaurus Apatosaurus Appalachiosaurus Apsaravis Aquilarhinus Aquilops Arackar Aragosaurus Aralosaurus Aratasaurus Archaeoceratops Archaeoceratops Archaeodontosaurus Archaeopteryx Archaeopteryx Archaeorhynchus Archaeornithoides Archaeornithomimus Archaeornithomimus Archaeornithura Arcovenator Arcusaurus Arenysaurus Argentinosaurus Argyrosaurus Aristosuchus Arkansaurus Arkharavia Arrhinoceratops Arrudatitan Asfaltovenator Asiaceratops Asiaceratops Asiahesperornis Asiatosaurus Asiatosaurus Astrophocaudia Asylosaurus Atacamatitan Atlantosaurus Atlantosaurus Atlasaurus Atlascopcosaurus Atrociraptor Atsinganosaurus Aublysodon Aucasaurus Augustynolophus Auroraceratops Aurornis Australodocus Australotitan Australovenator Austrocheirus Austroposeidon Austroraptor Austrosaurus Avaceratops Aviatyrannis Avimimus Avimimus Avisaurus

Baalsaurus Bactrosaurus Bactrosaurus Bagaceratops Bagaraatan Bagualia Bagualosaurus Bahariasaurus Bainoceratops Bainoceratops Bajadasaurus Balaur Bambiraptor Banji Bannykus Baotianmansaurus Baptornis Barapasaurus Barilium Barosaurus Barrosasaurus Barsboldia Baryonyx Bashanosaurus Batyrosaurus Batyrosaurus Baurutitan Bauxitornis Bayannurosaurus Beg Beibeilong Beiguornis Beipiaognathus Beipiaosaurus Beishanlong Bellusaurus Berberosaurus Berthasaura Bicentenaria Bienosaurus Bissektipelta Bistahieversor Blasisaurus Blikanasaurus Bohaiornis Bolong Boluochia Bonapartenykus Bonapartenykus Bonapartesaurus Bonatitan Bonitasaura Borealopelta Borealosaurus Boreonykus Borogovia Bothriospondylus Brachiosaurus Brachyceratops Brachylophosaurus Brachytrachelopan Bradycneme Brasilotitan Bravasaurus Bravoceratops Breviceratops Brighstoneus Brodavis Brodavis Brodavis Brodavis Brohisaurus Brontomerus Brontosaurus Buitreraptor Burianosaurus Buriolestes Byronosaurus

Caenagnathasia Caenagnathus Caihong Calamosaurus Callovosaurus Camarasaurus Camarasaurus Camarasaurus Camarasaurus Camarillasaurus Camelotia Camposaurus Camptodontornis Camptosaurus Campylodoniscus Canadaga Canardia Carcharodontosaurus Carcharodontosaurus Cardiodon Carnotaurus Caseosaurus Cathartesaura Caudipteryx Caudipteryx Cedarosaurus Cedarpelta Cedrorestes Centrosaurus Ceramornis Cerasinops Ceratonykus Ceratops Ceratosaurus Ceratosaurus Ceratosaurus Ceratosuchops Cerebavis Cetiosauriscus Cetiosaurus Changchengornis Changchunsaurus Changmiania Changyuraptor Changzuiornis Chaoyangia Chaoyangsaurus Charonosaurus Chasmosaurus Chasmosaurus Chasmosaurus Chebsaurus Chenanisaurus Chialingosaurus Chiappeavis Chiayusaurus Chiayusaurus Chilantaisaurus Chilesaurus Chindesaurus Chingkankousaurus Chinshakiangosaurus Chirostenotes Choconsaurus Chondrosteosaurus Chongmingia Choyrodon Chromogisaurus Chuandongocoelurus Chuanjiesaurus Chuanqilong Chubutisaurus Chungkingosaurus Chupkaornis Chuxiongosaurus Cimolopteryx Cimolopteryx Citipati Citipes Claosaurus Coahuilaceratops Coelophysis Coelurus Colepiocephale Coloradisaurus Comahuesaurus Compsognathus Compsosuchus Concavenator Conchoraptor Concornis Condorraptor Confuciusornis Confuciusornis Confuciusornis Confuciusornis Convolosaurus Coronosaurus Corythoraptor Corythosaurus Corythosaurus Craspedodon Craterosaurus Cretaaviculus Crichtonpelta Crichtonsaurus Cristatusaurus Crittendenceratops Cruxicheiros Cryolophosaurus Cumnoria

Dacentrurus Daemonosaurus Dakotadon Dakotaraptor Dalianraptor Daliansaurus Dandakosaurus Daspletosaurus Daspletosaurus Datanglong Datonglong Datousaurus Daurlong Daxiatitan Deinocheirus Deinodon Deinonychus Deltadromeus Demandasaurus Denversaurus Diabloceratops Diamantinasaurus Dicraeosaurus Dilong Dilophosaurus Diluvicursor Dineobellator Dinheirosaurus Diplodocus Diplodocus Diplodocus Dongbeititan Dongyangopelta Dongyangosaurus Draconyx Dracoraptor Dracovenator Dreadnoughtus Dromaeosauroides Dromaeosaurus Dromiceiomimus Drusilasaura Dryosaurus Dryptosaurus Dubreuillosaurus Duriatitan Duriavenator Dynamoterror Dyoplosaurus Dysalotosaurus Dysganus Dysganus Dysganus Dysganus Dyslocosaurus Dzharaonyx Dzharatitanis

Echinodon Edmontonia Edmontonia Edmontosaurus Edmontosaurus Efraasia Einiosaurus Ekrixinatosaurus Elaltitan Elaphrosaurus Elmisaurus Elopteryx Elrhazosaurus Emausaurus Enaliornis Enaliornis Enaliornis Enantiophoenix Enigmosaurus Eoabelisaurus Eocarcharia Eoconfuciusornis Eocursor Eodromaeus Eogranivora Eolambia Eomamenchisaurus Eoraptor Eosinopteryx Eotrachodon Eotriceratops Eotyrannus Eousdryosaurus Epachthosaurus Epanterias Epichirostenotes Epidexipteryx Equijubus Erectopus Erketu Erliansaurus Erlikosaurus Erythrovenator Eshanosaurus Eucamerotus Eucercosaurus Eucnemesaurus Eucnemesaurus Euhelopus Euoplocephalus Europasaurus Europatitan Europelta Euskelosaurus Eustreptospondylus Evgenavis Evgenavis

Falcarius Falcatakely Ferganasaurus Ferrisaurus Foraminacephale Fosterovenator Fostoria Fruitadens Fukuipteryx Fukuiraptor Fukuisaurus Fukuititan Fukuivenator Fulgurotherium Fumicollis Fushanosaurus Fusuisaurus Futalognkosaurus Fylax

Galeamopus Galeamopus Galleonosaurus Gallimimus Gallornis Galvesaurus Gannansaurus Gansus Gansus Ganzhousaurus Gargantuavis Gargoyleosaurus Garrigatitan Garudimimus Gasosaurus Gasparinisaura Gastonia Gastonia Geminiraptor Genusaurus Genyodectes Geranosaurus Gettyia Gideonmantellia Giganotosaurus Gigantoraptor Gigantspinosaurus Gilmoreosaurus Gilmoreosaurus Gilmoreosaurus Gilmoreosaurus Giraffatitan Glacialisaurus Glishades Glyptodontopelta Gnathovorax Gobihadros Gobioolithus Gobioolithus Gobipteryx Gobiraptor Gobisaurus Gobititan Gobivenator Gojirasaurus Gondwanatitan Gongpoquansaurus Gongxianosaurus Gorgosaurus Goyocephale Graciliceratops Graciliraptor Gravitholus Gryphoceratops Gryposaurus Gryposaurus Gryposaurus Gryposaurus Guaibasaurus Gualicho Guanlong Guemesia

Hadrosaurus Haestasaurus Hagryphus Halimornis Halszkaraptor Hamititan Hanssuesia Haplocanthosaurus Haplocanthosaurus Haplocheirus Harpymimus Haya Heptasteornis Herrerasaurus Hesperonychus Hesperornis Hesperornis Hesperornis Hesperornis Hesperornis Hesperornis Hesperornis Hesperornis Hesperornis Hesperornis Hesperornis Hesperornithoides Hesperosaurus Heterodontosaurus Hexing Hexinlusaurus Heyuannia Hippodraco Histriasaurus Hollanda Homalocephale Hongshanornis Hoplitosaurus Horshamosaurus Hortalotarsus Huabeisaurus Hualianceratops Huallasaurus Huanansaurus Huanghetitan Huangshanlong Huaxiagnathus Huayangosaurus Hudiesaurus Huehuecanauhtlus Huinculsaurus Hulsanpes Hungarosaurus Hylaeosaurus Hypacrosaurus Hypacrosaurus Hypselosaurus Hypselospinus Hypsilophodon

Iaceornis Iberospinus Ibirania Ichthyornis Ichthyovenator Ignavusaurus Iguanacolossus Iguanodon Iguanodon Iguanodon Ilokelesia Imperobator Incisivosaurus Indosaurus Indosuchus Ingentia Intiornis Invictarx Irisosaurus Irritator Isaberrysaura Isanosaurus Isasicursor Ischioceratops Isisaurus Issi Itapeuasaurus Itemirus Iuticosaurus Iyuku

Jainosaurus Jakapil Jaklapallisaurus Janenschia Jaxartosaurus Jeholornis Jeholornis Jeholornis Jeholosaurus Jeyawati Jianchangornis Jianchangosaurus Jiangjunosaurus Jiangshanosaurus Jiangxisaurus Jianianhualong Jibeinia Jinbeisaurus Jinfengopteryx Jingshanosaurus Jinguofortis Jintasaurus Jinyunpelta Jinzhousaurus Jiuquanornis Jiutaisaurus Jixiangornis Jobaria Judiceratops Judinornis Juratyrant Juravenator

Kaatedocus Kaijiangosaurus Kaijutitan Kakuru Kamuysaurus Kangnasaurus Kansaignathus Kaririavis Karongasaurus Katepensaurus Kayentavenator Kazaklambia Kelmayisaurus Kelumapusaura Kentrosaurus Kerberosaurus Khaan Khinganornis Kholumolumo Khulsanurus Kileskus Kinnareemimus Klamelisaurus Kol Kompsornis Kookne Koparion Koreaceratops Koreanosaurus Koshisaurus Kosmoceratops Kotasaurus Kritosaurus Kryptops Kulceratops Kulindadromeus Kunbarrasaurus Kundurosaurus Kuru Kurupi Kuszholia

Labocania Laevisuchus Laiyangosaurus Lajasvenator Lamarqueavis Lamarqueavis Lamarqueavis Lambeosaurus Lambeosaurus Lambeosaurus Lanzhousaurus Lapampasaurus Laplatasaurus Lapparentosaurus Laquintasaura Latenivenatrix Latirhinus Latirhinus Lavocatisaurus Leaellynasaura Ledumahadi Leinkupal Leonerasaurus Lepidus Leptoceratops Leptorhynchos Leshansaurus Lesothosaurus Lessemsaurus Levnesovia Lexovisaurus Leyesaurus Liaoceratops Liaoningosaurus Liaoningotitan Liaoningvenator Ligabueino Ligabuesaurus Liliensternus Limaysaurus Limenavis Limusaurus Lingwulong Lingyuanosaurus Linhenykus Linheraptor Linhevenator Lirainosaurus Liubangosaurus Llukalkan Lohuecotitan Longicrusavis Longipteryx Longirostravis Longusunguis Lophorhothon Lophostropheus Loricatosaurus Losillasaurus Lourinhasaurus Luanchuanraptor Lucianovenator Lufengosaurus Lufengosaurus Luoyanggia Lurdusaurus Lusotitan Lusovenator Lycorhinus Lythronax

Maaqwi Machairasaurus Machairoceratops Macrocollum Macrogryphosaurus Macrurosaurus Macrurosaurus Magnamanus Magnapaulia Magnosaurus Magyarosaurus Magyarosaurus Mahakala Mahuidacursor Maiasaura Maip Majungasaurus Malarguesaurus Malawisaurus Maleevus Mamenchisaurus Mamenchisaurus Mamenchisaurus Mamenchisaurus Mamenchisaurus Mamenchisaurus Manidens Mantellisaurus Mapusaurus Maraapunisaurus Marmarospondylus Marshosaurus Martharaptor Masiakasaurus Massospondylus Massospondylus Matheronodon Maxakalisaurus Mbiresaurus Medusaceratops Megalosaurus Megapnosaurus Megapnosaurus Megaraptor Mei Melanorosaurus Mendozasaurus Menefeeceratops Mengciusornis Menucocelsior Meraxes Mercuriceratops Meroktenos Metriacanthosaurus Microceratus Microceratus Micropachycephalosaurus Microraptor Microraptor Microraptor Microvenator Mierasaurus Minmi Minotaurasaurus Miragaia Mirarce Mirischia Mnyamawamtuka Moabosaurus Mochlodon Mochlodon Mongolostegus Monkonosaurus Monolophosaurus Mononykus Montanoceratops Morelladon Moros Morrosaurus Mosaiceratops Murusraptor Mussaurus Muttaburrasaurus Muyelensaurus Mymoorapelta Mystiornis

Naashoibitosaurus Nambalia Nankangia Nanningosaurus Nanosaurus Nanshiungosaurus Nanuqsaurus Nanyangosaurus Narambuenatitan Narindasaurus Nasutoceratops Natovenator Navajoceratops Nebulasaurus Nedcolbertia Nedoceratops Neimongosaurus Nemegtomaia Nemegtonykus Neogaeornis Neosodon Neovenator Neuquenornis Neuquenraptor Ngwevu Nhandumirim Niebla Nigersaurus Ningyuansaurus Ninjatitan Niobrarasaurus Nipponosaurus Noasaurus Nodocephalosaurus Nodosaurus Nomingia Nopcsaspondylus Normanniasaurus Notatesseraeraptor Nothronychus Notoceratops Notocolossus Notohypsilophodon Nqwebasaurus Nullotitan Nuthetes

Oceanotitan Ohmdenosaurus Ojoceratops Ojoraptorsaurus Oksoko Olorotitan Omeisaurus Omeisaurus Omeisaurus Omeisaurus Omeisaurus Omeisaurus Omeisaurus Omeisaurus Omnivoropteryx Ondogurvel Oohkotokia Oplosaurus Orkoraptor Ornatops Ornitholestes Ornithomimus Ornithomimus Ornithomimus Ornithopsis Orodromeus Orthomerus Oryctodromeus Osmakasaurus Ostafrikasaurus Ostromia Ouranosaurus Overoraptor Overosaurus Oviraptor Owenodon Oxalaia Ozraptor

Pachycephalosaurus Pachyrhinosaurus Pachyrhinosaurus Pachyrhinosaurus Padillasaurus Palaeopteryx Palintropus Paludititan Pampadromaeus Pamparaptor Panamericansaurus Pandoravenator Panguraptor Panoplosaurus Panphagia Pantydraco Papiliovenator Parabohaiornis Parahesperornis Parahesperornis Parahongshanornis Paralitherizinosaurus Paranthodon Parapengornis Pararhabdodon Parasaurolophus Parasaurolophus Parasaurolophus Paraxenisaurus Pareisactus Parksosaurus Paronychodon Paronychodon Parvicursor Pasquiaornis Pasquiaornis Patagonykus Patagonykus Patagopteryx Patagosaurus Patagotitan Pawpawsaurus Pectinodon Pedopenna Pegomastax Pelecanimimus Pellegrinisaurus Peloroplites Pelorosaurus Pendraig Penelopognathus Pengornis Pentaceratops Perijasaurus Petrobrasaurus Phaedrolosaurus Philovenator Phuwiangosaurus Phuwiangvenator Phyllodon Piatnitzkysaurus Pilmatueia Pinacosaurus Pinacosaurus Piscivoravis Pitekunsaurus Piveteausaurus Planicoxa Plateosaurus Plateosaurus Plateosaurus Platypelta Plesiohadros Pneumatoraptor Poekilopleuron Polacanthus Polarornis Polyodontosaurus Polyonax Potamornis Powellvenator Pradhania Prenocephale Prenoceratops Priconodon Proa Probactrosaurus Probrachylophosaurus Proceratosaurus Procompsognathus Proornis Propanoplosaurus Prosaurolophus Protarchaeopteryx Protoceratops Protoceratops Protognathosaurus Protohadros Psittacosaurus Psittacosaurus Psittacosaurus Psittacosaurus Psittacosaurus Psittacosaurus Psittacosaurus Psittacosaurus Psittacosaurus Psittacosaurus Psittacosaurus Psittacosaurus Pterospondylus Puertasaurus Pukyongosaurus Pulanesaura Punatitan Pycnonemosaurus Pyroraptor

Qantassaurus Qianzhousaurus Qiaowanlong Qijianglong Qinlingosaurus Qiupalong Qiupanykus Quetecsaurus Quilmesaurus

Rahiolisaurus Rahonavis Rajasaurus Rapator Rapaxavis Rapetosaurus Raptorex Ratchasimasaurus Rativates Rayososaurus Rebbachisaurus Regaliceratops Regnosaurus Rhabdodon Rhabdodon Rhadinosaurus Rhinorex Rhoetosaurus Rhomaleopakhus Riabininohadros Rinchenia Rinconsaurus Riojasaurus Riparovenator Rugocaudia Rugops Rukwatitan Ruyangosaurus

Sahaliyania Saichania Saltriovenator Sanjuansaurus Sanpasaurus Santanaraptor Sanxiasaurus Sapeornis Sarahsaurus Sarcosaurus Sarmientosaurus Saturnalia Saurolophus Saurolophus Sauroniops Sauropelta Saurophaganax Sauroplites Sauroposeidon Saurornithoides Saurornitholestes Saurornitholestes Savannasaurus Scansoriopteryx Scelidosaurus Schizooura Schleitheimia Scipionyx Sciurumimus Scolosaurus Scolosaurus Scutellosaurus Secernosaurus Sefapanosaurus Segisaurus Segnosaurus Seitaad Sektensaurus Serendipaceratops Serikornis Shamosaurus Shanag Shantungosaurus Shanweiniao Shanxia Shanyangosaurus Shaochilong Shengjingornis Shenqiornis Shenzhousaurus Shidaisaurus Shingopana Shishugounykus Shixinggia Shri Shuangbaisaurus Shuangmiaosaurus Shunosaurus Shuvuuia Siamodon Siamosaurus Siamotyrannus Siamraptor Siats Sibirotitan Sierraceratops Sigilmassasaurus Silvisaurus Similicaudipteryx Sinocalliopteryx Sinocephale Sinoceratops Sinornithoides Sinornithomimus Sinornithosaurus Sinornithosaurus Sinosauropteryx Sinosaurus Sinosaurus Sinotyrannus Sinovenator Sinraptor Sinraptor Sinusonasus Sirindhorna Skorpiovenator Smitanosaurus Songlingornis Sonidosaurus Sonorasaurus Soriatitan Soroavisaurus Spectrovenator Sphaerotholus Sphaerotholus Sphaerotholus Spiclypeus Spinophorosaurus Spinops Spinosaurus Spinostropheus Staurikosaurus Stegoceras Stegoceras Stegopelta Stegosaurus Stegosaurus Stegosaurus Stegouros Stellasaurus Stenonychosaurus Stenopelix Stokesosaurus Streptospondylus Struthiomimus Struthiosaurus Struthiosaurus Struthiosaurus Styracosaurus Styracosaurus Suchomimus Suchosaurus Suchosaurus Sulcavis Supersaurus Suskityrannus Suuwassea Suzhousaurus Syngonosaurus Szechuanosaurus

Tachiraptor Talarurus Talenkauen Talos Tamarro Tambatitanis Tangvayosaurus Tanius Tanius Tanycolagreus Taohelong Tapuiasaurus Tarbosaurus Tarchia Tarchia Tarchia Tastavinsaurus Tatankacephalus Tataouinea Tatisaurus Taurovenator Tawa Tazoudasaurus Tehuelchesaurus Telmatosaurus Tendaguria Tengrisaurus Tenontosaurus Tenontosaurus Teratophoneus Terminocavus Tethyshadros Texacephale Texasetes Thanatotheristes Thanos Thecocoelurus Thecodontosaurus Theiophytalia Therizinosaurus Thescelosaurus Tianyulong Tianyuornis Tianyuraptor Tianzhenosaurus Tienshanosaurus Timimus Timurlengia Tingmiatornis Titanoceratops Titanosaurus Titanosaurus Tlatolophus Tochisaurus Tonganosaurus Tongtianlong Tornieria Torosaurus Torosaurus Torvosaurus Torvosaurus Torvosaurus Tototlmimus Tralkasaurus Transylvanosaurus Tratayenia Traukutitan Triceratops Triceratops Trierarchuncus Trigonosaurus Trinisaura Triunfosaurus Troodon Tsaagan Tsagantegia Tsintaosaurus Tuebingosaurus Tugulusaurus Tuojiangosaurus Turanoceratops Turiasaurus Tylocephale Tyrannosaurus Tyrannotitan

Uberabatitan Ubirajara Udanoceratops Ultrasaurus Ulughbegsaurus Unaysaurus Unenlagia Unenlagia Unescoceratops Unquillosaurus Urbacodon Utahceratops Utahraptor Uteodon

Vahiny Valdoraptor Valdosaurus Vallibonavenatrix Variraptor Vayuraptor Vectaerovenator Vectiraptor Vegavis Velafrons Velocipes Velociraptor Velociraptor Velocisaurus Venenosaurus Vescornis Vespersaurus Veterupristisaurus Viavenator Vitakridrinda Volgatitan Volkheimeria Vorona Vouivria Vulcanodon

Wakinosaurus Walgettosuchus Wamweracaudia Wannanosaurus Weewarrasaurus Wellnhoferia Wendiceratops Wiehenvenator Wintonotitan Wuerhosaurus Wuerhosaurus Wulagasaurus Wulatelong Wulong

Xenoceratops Xenoposeidon Xenotarsosaurus Xianshanosaurus Xiaosaurus Xiaotingia Xingtianosaurus Xingxiulong Xinjiangovenator Xinjiangtitan Xiongguanlong Xixianykus Xixiasaurus Xiyunykus Xuanhanosaurus Xuanhuaceratops Xunmenglong Xuwulong

Yamaceratops Yamatosaurus Yandangornis Yangavis Yangchuanosaurus Yangchuanosaurus Yanornis Yanornis Yaverlandia Yehuecauhceratops Yi Yimenosaurus Yingshanosaurus Yinlong Yixianornis Yixianosaurus Yizhousaurus Yongjinglong Ypupiara Yuanchuavis Yuanmousaurus Yueosaurus Yulong Yunganglong Yunmenglong Yunnanosaurus Yunnanosaurus Yunnanosaurus Yunyangosaurus Yurgovuchia Yutyrannus Yuxisaurus

Zalmoxes Zalmoxes Zanabazar Zapalasaurus Zaraapelta Zby Zephyrosaurus Zhanghenglong Zhenyuanlong Zhongjianornis Zhongjianosaurus Zhongornis Zhongyuansaurus Zhouornis Zhuchengceratops Zhuchengtyrannus Ziapelta Zigongosaurus Zizhongosaurus Zuniceratops Zuolong Zuoyunlong Zupaysaurus Zuul

455 notes

·

View notes

Text

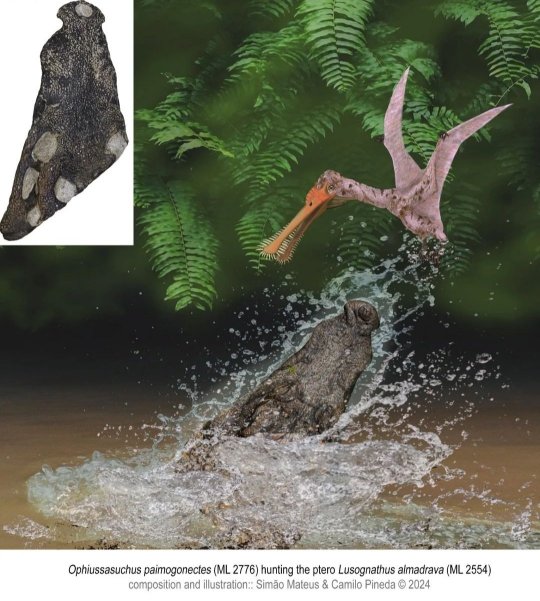

Ophiussasuchus: The Lourinhã Goniopholid

Not even a full three weeks into 2024 and we already have three new pseudosuchians, personally, I'm pretty satisfied with this developement.

The newest one is Ophiussasuchus paimogonectes ("crocodile from Portugal that swims at Paimogo beach"), a goniopholid Neosuchian from the Late Jurassic Lourinhã Formation of Portugal.

Ophiussasuchus is known from a single specimen, but one thats quite complete, preserving almost the entirety of the skull in 3D and only missing a chunk of the right side of the end of the skull.

The skull of Ophiussasuchus is mesorostine and platyrostral. In simple terms, its of medium length and width and has a flattened skull. Platyrostry is pretty much the standard for goniopholids, but mesorostry is more noticable in that there are some other genera in the group with short snouts (like Nannosuchus) and long snouts (like Anteopthalmosuchus and Hulkepholis). Another more general feature of this animal is that it was a medium-sized member of its family, with estimates suggesting a length of somewhere between 2.5 to 3 meters.

As often the case, the devil lies in the detail. Ophiussasuchus is thought to have been most closely related to Hulkepholis and Anteophthalmosuchus, two goniopholids from the Early Cretaceous of Europe. However it displays several features that indicate an intermediate position. A nasopharyngeal duct is visible on the palate, but in its closest relatives the duct is enclosed and in the more basal American forms the duct is more open. Interestingly, the palate also features small palatal fenestrae, which are not seen in any other goniopholids aside from Siamosuchus. Interestingly, these two features are not just leftovers from its ancestry. Analysis suggest that the palate of the ancestor of Ophiussasuchus likely looked like that of the other European taxa, which in turn means that this anatomy was reversed in Ophiussasuchus. It's unclear if Ophiussasuchus simply lost that anatomy or if it actually converged with the more basal forms.

Anteophthalmosuchus and Hulkepholis, longirostrine relatives of Ophiussasuchus from the early Cretaceous. Figure from Arribas et al. 2019

Ophiussasuchus lived during the Late Jurassic (Kimmeridgian to Tithonian) in the Lourinhã Formation of Portugal. The Lourinha is perhaps most famous as "Europe's Morrison", sharing much fauna with its American counterpart. Just as an example both formations feature Allosaruus, Torvosaurus and some animals found in the Lourinhã Formation are at the very least related to American forms. Examples for the latter are Lusotitan and Brachiosaurus, Dinheirosaurus and Supersaurus as well as Miragaia and Alcovasaurus.

Goniopholids are also present in both formations, the Morrison featuring Amphicotylus, Eutretauranosuchus and Diplosaurus and Lourinhã being home to Ophiussasuchus.

Reconstruction below by Simão Mateus and Camilo Pineda

Obligatory wikipedia and paper links

Ophiussasuchus - Wikipedia

A new Portuguese goniopholidid (palaeo-electronica.org)

#Lourinhã Formation#goniopholidae#pseudosuchia#croc#crocodile#ophiussasuchus#prehistory#jurassic#portugal#paleontology#palaeoblr#long post

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Caihong vs Hesperornithoides

Factfiles:

Caihong juji

Artwork by @i-draws-dinosaurs, written by @i-draws-dinosaurs

Name meaning: Rainbow with big crest

Time: 161 million years old (Oxfordian stage of the Late Jurassic)

Location: Tiaojishan Formation, China

It’s always a special treat to hear the announcement of a dinosaur with known colours, because it gives the most direct impression of how truly stunning these animals would have been to witness in real life. And Caihong might just be the most spectacular of them all so far, described in 2018 from an immaculate full-body fossil that preserves detailed feathers! Caihong’s feathers are longer than some other floofy dinosaurs, and would have had the appearance of a luxurious mane along its neck. Not only that, the fossil preserves feather microstructures that in life would have made this dinosaur gloriously iridescent!

Now iridescent dinosaurs aren’t new, Microraptor has been decked out in fabulous starling-esque plumage for a while now, but Caihong absolutely takes it to the next level. Its whole body was covered in iridescent black, including the enormous tail, but the real star of the show are the platelet-like melanosomes found on the head, neck, and the base of the tail. Different from the usual iridescent melanosomes, the structure of these tiny organelles reflects brilliantly iridescent colours, like those on the heads of hummingbirds and particularly the bright purple feathers on the necks of the trumpeter family. Caihong would have put on an absolutely dazzling jewel-toned display in the treetops or on the forest floor of prehistoric China!

Hesperornithoides miessleri

Artwork by Gabriel Ugueto, written by @zygodactylus

Name Meaning: Miessler’s Western Bird Form

Time: 156 to 147 million years ago (Kimmeridgian to Tithonian stages of the Late Jurassic)

Location: Jimbo Quarry, Morrison Formation, Wyoming

Say hello to Lori! Hesperornithoides is a vital newly named dinosaur known from material that had been excavated a few decades ago, taking that long to describe properly. You see, while we have Avialans - “protobirds” - from the Late Jurassic, we don’t have other birdy dinosaurs we’d expect from this time, such as Dromaeosaurs and Troodontids. However, with the description of Lori and other troodons from places like the Morrison, we finally have those missing links! Having more feathered dinosaurs known from times before Archaeopteryx is important for adding more robust evidence to the idea that birds are living dinosaurs - not that we need much after the discovery of the Jehol biota, but, the more evidence the better. At about a meter long and half a meter high, it is possible that Hesperornithoides was a juvenile, and may have gotten at least somewhat bigger. A slender animal with raised sickle claws, like other Troodontids, it would have looked like a small pointy bird in its environment. In fact, Hesperornithoides showcases that we have yet to find everything from the Morrison Formation - it is possible that even more mysteries lie in this interesting and famous extinct ecosystem. Lori lived in a transitional wetland environment, which would have gone through extreme seasonality. As Lori was found in a resting position, it seems that this is where Hesperornithoides lived, rather than just having been preserved there. It probably used its wings to help with predatory behaviors and in display. Its environment, the Morrison Formation, is one of the most diverse dinosaur ecosystems and one of the best known; however, its organization is something of a mess, so it isn’t clear which exact habitats Lori would have been associated with. It is a safe bet to say, however, that it lived alongside dinosaurs similar to Camarasaurus, Camptosaurus, Dryosaurus, Alcovasaurus, Gargoyleosaurus, Hesperosaurus, Stegosaurus, Haplocanthosaurus, Dyslocosaurus, Apatosaurus, Brontosaurus, Barosaurus, Diplodocus, Galeamopus, Supersaurus, Kaatedocus, Allosaurus, Fosterovenator, Coelurus, and Ornitholestes.

DMM Round One Masterpost

#dmm#dinosaur march madness#dinosaurs#dmm round one#dmm rising stars#palaeoblr#paleontology#bracket#march madness#polls#caihong#hesperornithoides

134 notes

·

View notes

Text

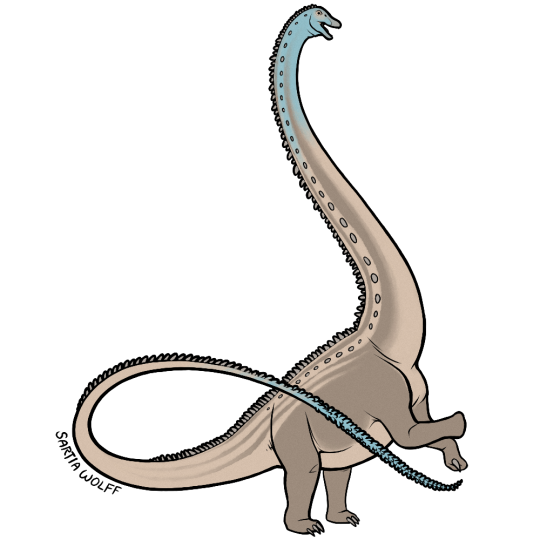

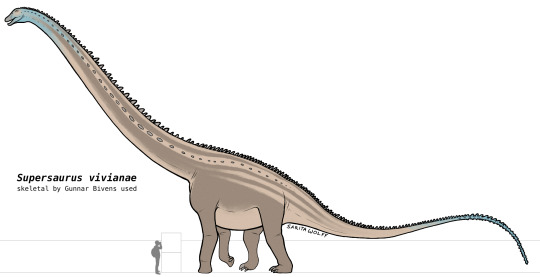

#Archovember Day 7 - Supersaurus vivianae

Living in Late Jurassic North America, the diplodocid Supersaurus vivianae was one of the largest and longest sauropods to ever exist. With larger specimens reaching 33–35 metres (108–115 ft) long and weighing an estimated 35–40 metric tons (39–44 short tons), it was matched only by the Late Cretaceous titanosaur Argentinosaurus.

As a diplodocid, Supersaurus would have used it’s long, peg-like teeth to strip food from branches and swallow it without chewing, instead relying on gastroliths (small stones) to break down plant material in its gizzard. Due to the high stress stripping branches would place on its teeth, diplodocids continuously replaced their teeth throughout their lives, usually in less than 35 days! Supersaurus could have had as many as 5 teeth developing per tooth socket.

Supersaurus, like other diplodocids, had a long, whiplike tail which tapered at the end. They could have snapped this tail like a bullwhip, generating a sonic boom. This could have been used in mating displays or to ward off predators.

Being the largest animals living at the time, there weren’t many, if any, predators in the Morrison Formation that could have preyed on adult Supersauruses. However, young Supersauruses would have had a multitude of large theropods to look out for, including Allosaurus, Saurophaganax, Ceratosaurus, Torvosaurus, and Marshosaurus. Supersaurus would have lived alongside a variety of other sauropods such as Haplocanthosaurus, Smitanosaurus, Amphicoelias, Apatosaurus, Brontosaurus, Diplodocus, Brachiosaurus, Camarasaurus, Dystrophaeus, and the rare Barosaurus. There were a lot of Ornithischians in this formation as well, though not as numerous and diverse as the sauropods. They included the early ornithopods Camptosaurus, Dryosaurus, Nanosaurus, and Uteodon, the stegosaurians Alcovasaurus, Hesperosaurus, and Stegosaurus, the ankylosaurians Gargoyleosaurus and Mymoorapelta, and the heterodontosaur Fruitadens.

#my art#SaritaDrawsPalaeo#Supersaurus#Supersaurus vivianae#diplodocid#sauropods#saurischians#dinosaurs#archosaurs#archosauromorphs#reptiles#Archovember#Archovember2023

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

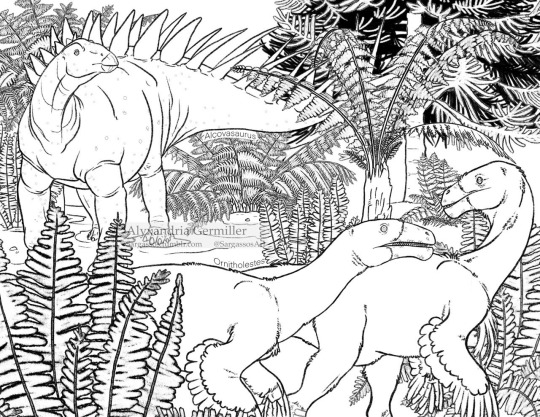

Dinovember, day 26; This alcovasaurus is highly suspicious of these passing ornitholestes.

This is actually the last page of dinosaurs I have. The next one is a pterosaur, and the last three will be marine reptiles. But they're all fossils from Morrison or Sundance, and I wanted to include them! Onward! The end is in sight!

EDIT, 1/11/22: This entire Dinovember series has been compiled and is now available for purchase on Gumroad! The pages can be printed, or thrown into a digital program! Check it out HERE!

#art#digital art#sketch#lineart#coloring book#dinovember coloring book#dinovember#dinovember 2021#drawdinovember#dinosaur#dinosaurs#morrison formation#late jurassic#theropod#ornitholestes#stegosaurid#alcovasaurus#miragaia#miragaia longispinus

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alcovasaurus based on Vritra from FGO.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

✨🖤💛dinosaur gallery🖤💛✨

prints (large and mini!) available in my store!

——— http://fleebites.storenvy.com

#paleontology#paleo art#sauropod#sauropods#dreadnoughtus#dreadnoughtus schrani#diplodocus#nyctosaur#ankylosaurus#quetzalcoatlus#styracosaurus#ichthyosaur#helicoprion#stegosaurus#alcovasaurus#deinonychus#raptor#dinosaurs#dinosaur

53 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Day 8 of my palette challenge (palettes found here) brings the first of the 2016 dinosaurs - Alcovasaurus in #70, trying to get rid of an itch.

132 notes

·

View notes

Text

Day 14: Alcovasaurus longispinus (Miragaia longicollum)

Alcovasaurus is once be a kentrosaurus sp, then it supposed be a stegosaurid, and now more Dacentrurinae as this specie is renamed to Miragaia longicollum.

#my art#dinosaur#animals#dinosaurs#paleoart#dinosauria#ornithoscelida#ornithischia#genasauria#thyreophora#stegosauria#stegosauridae#dacentrurinae#alcovasaurus#miragaia#late jurassic#procreate5x#procreate#draw dinovember#dinovember#artists on tumblr

0 notes

Photo

Morrisonite è il paleontologo al Villaggio delle Montagne.

Studia gli antichi animali che abitavano il pianeta miliardi di anni prima dell'arrivo delle Gemme, e i reperti sotto l'Arcipelago, che è un pezzo di profondissima crosta terrestre sopraelevata da un fortissimo evento meteorico, sono tantissimi.

Morrisonite è la Gemma più antica dell'intero Arcipelago, e del pianeta intero, compreso Adamant! Si è formato durante il "Giurassico", un'epoca geologica talmente antica di cui ormai non rimane molto- se non lui stesso, e le ossa di cui è formato.

(Le sue gambe appartengono a Ceratosaurus Nasicornis, la coda a Alcovasaurus/Miragaia Longispinus, le braccia a Tanycolagreus Topwilsoni, i denti a Fruitadens Haagarorum e i capelli erano la coda di un Brontosaurus Excelsius.)

Lui non ricorda niente, tuttavia, se non la sua nascita, prima dell'avvento delle Gemme dall'Isola Originaria ma successiva a Yttrite e Orpimento.

È stato lui a scoprire che gli antenati degli Admirabilis erano degli esseri strani chiamati "umani", di cui ha ritrovato diversi frammenti fossili.

Assieme a Pezzottaite sta cercando di comprendere di più su questa specie estinta.

#houseki no kuni#land of the lustrous#houseki no kuni oc#land of the lustrous oc#hnk oc#lotl oc#Gems of the Mountains#Morrisonite#i do things

22 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Stegosaurus”/ “Alcovasaurus” longispinus is actually a species of Miragaia!?

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Australia's Largest Dinosaur

Dinosaur of the day Neovenator, an apex predator from the UK with a sensitive face.

Interview with Jo Pegler and Corey Richards, laboratory coordinator and operations & marketing coordinator at the Eronmanga Natural History Museum in southwest Queensland Australia. If you can't visit them in person, you can see there work at enhm.com.au or on twitter @EromangaNHM

In dinosaur news this week:

A new Miragaia specimen solidifies the genus, but eliminates Alcovasaurus

A rare three-dimensionally preserved dinosaur/bird, Fukuipteryx, was described from Japan

The Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History just assessed their iconic mural “The Age of Reptiles”

The Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade had a T. rex float named Rexy

The American Museum of Natural History decorated a tree with more than 800 origami dinosaurs

This episode is brought to you in part by Why Dinosaurs? The feature length documentary celebrating dinosaurs and the people who love them, created by father and son team Tony and James Pinto, support them and get perks on Indiegogo.

To get access to lots of patron only content check out https://www.patreon.com/iknowdino

For links to every news story, all of the details we shared about Neovenator, links from Jo Pegler and Corey Richards, and our fun fact check out https://iknowdino.com/Neovenator-Episode-263/

Check out this episode!

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alcovasaurus longispinus

By José Carlos Cortés on @ryuukibart

PLEASE SUPPORT US ON PATREON. EACH and EVERY DONATION helps to keep this blog running! Any amount, even ONE DOLLAR is APPRECIATED! IF YOU ENJOY THIS CONTENT, please CONSIDER DONATING!

Name: Alcovasaurus longispinus

Name Meaning: Alcova Reptile

First Described: 2016

Described By: Galton and Carpenter

Classification: Dinosauria, Ornithischia, Genasauria, Thyreophora, Eurypoda, Stegosauria, Stegosauridae

Alcovasaurus was a Stegosaur from the Morrison Formation of Wyoming, living about 150 million years ago in the Tithonian age of the Late Jurassic. It was originally thought to be a species of Stegosaurus, but then the specimens were damaged; later, the specimen was named under a new genus by Ulansky, who, well, let’s just say Ulansky, much like Malkani, likes to name a lot of new taxa in ways that aren’t official and aren’t diagnostic (and I’m not paying attention to Ulansky taxa, mainly for my own sanity). The material was then actually given its own genus name in an official way, and unique traits were found for the genus in having a rear spike pair that was the same size as the front pair, where other Stegosaurs with rear spike pairs had ones smaller than the front pair in their thagomizers. It also had a shorter tail than Stegosaurus.

Source:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alcovasaurus

Shout out goes to @convictionsofamadman!

#alcovasaurus#alcovasaurus longispinus#dinosaur#stegosaurs#palaeoblr#convictionsofamadman#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#dinosaurs#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature#factfile#Dìneasar#डायनासोर#ديناصور#ডাইনোসর#risaeðla#ڈایناسور#deinosor#恐龍#恐龙#динозавр#dinosaurio#공룡

42 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tweeted

Nueva propuesta para la #filogenia de #Stegosauria (aka el retorno de Miragaia y el exilio de Alcovasaurus... entre otros) https://t.co/POCTrazZgf

— Francisco Ortega (@frco_ortega) April 18, 2017

0 notes

Text

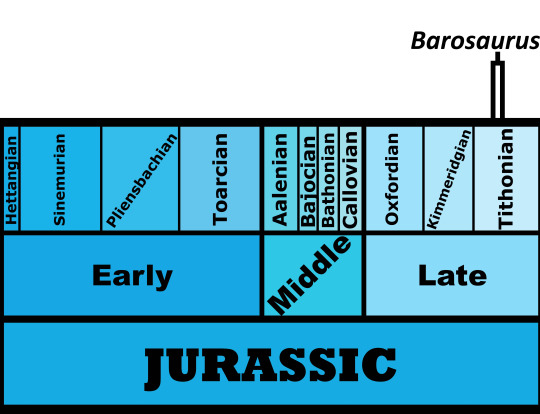

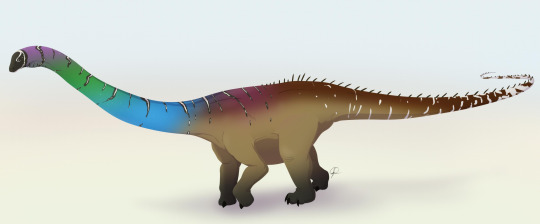

Barosaurus lentus

By Ripley Cook

Etymology: Heavy Reptile

First Described By: Marsh, 1890

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Sauropodomorpha, Bagualosauria, Plateosauria, Massopoda, Sauropodiformes, Anchisauria, Sauropoda, Gravisauria, Eusauropoda, Neosauropoda, Diplodocoidea, Diplodocimorpha, Flagellicaudata, Diplodocidae, Diplodocinae

Status: Extinct

Time and Place: Between 150 and 149 million years ago, in the Tithonian of the Late Jurassic

Barosaurus is known from the Brush Basin Member of the Morrison Formation in South Dakota, Utah, and Wyoming. Potential specimens of Barosaurus are known from other locations of the Morrison Formation; the entire range of this habitat at the time of Barosaurus is shown below in green (with the range of Barosaurus inside of it, in blue).

Physical Description: Barosaurus in a lot of ways is a fairly typical Diplodocid sauropod - long, large, and with a distinctive whip-tail. But, when you dig under the surface, Barosaurus has nothing truly “typical” about it. The neck of Barosaurus is next-level in its length - and the tail is ridiculous to match. In fact, the estimates of the length of Barosaurus get huge - it was probably more than twenty-six meters long, and some of the most upper estimates of Barosaurus have it at fifty meters long! This would make it one of, if not the, largest known dinosaurs - and certainly the longest! Though it does have a long tail, it differs in appearance from its cousin Diplodocus primarily by having a proportionally longer neck and shorter tail. It was also more slender than Apatosaurus, though it was longer than that contemporary. How did Barosaurus get such a long neck? It literally converted one of the back vertebrae into a neck vertebra! This is so fascinating that I can’t get over it - its close relatives, like Diplodocus, did not employ this to get a longer neck, indicating Barosaurus was using its long neck for things that its cousins were not. Barosaurus was also weird in not having as high of spines on its vertebrae as its cousin Diplodocus and other members of the group. In addition to all of that - it had shorter vertebrae in the tail, which made it shorter than in other members of this group! Interestingly, the bones on the underside of the tail were forked and had forward spikes, which would have given it similar strength to that of Diplodocus; it was probably still a whiptail like other members of this group, though not as much of one as its relatives.

By Slate Weasel, in the Public Domain

Of course, the distinctiveness of Barosaurus is primarily limited to the length of the animal and its spine. In terms of limbs, it had fairly identical limbs to its cousin Diplodocus, though it did have fairly long forelimbs compared to its cousin (by… an almost imperceptible amount, however). Though the feet of Barosaurus aren’t known, it is reasonable to suppose that it would have had feet similar to Diplodocus - with only one claw on the front feet and three small claws on the hind feet. The skull of Barosaurus is not known, but it probably would have been long and low, with peg-like teeth in the front of the jaws for grazing on plants. Its neck was not very flexible in the vertical sense, but it was much more flexible in sweeping from side to side. It is possible that there were spikes of some sort at the end of the tail, which would have packed quite a punch when the tail was used to whip other animals. And, finally, it would have been entirely - if not almost entirely - scaly all over its body. It is also possible that Barosaurus may have featured some brilliant colors, especially in the tail, for communication with other members of the species.

Diet: Barosaurus would have primarily fed on high-level vegetation, able to reach much of it at its natural neck height and then - on top of that - being able to rear up to 50 meters high via going on its hind legs. However, a lack of vertical reach in terms of neck flexibility means that it probably would have swept over a wide area for food, rather than going up and down in the tree level like other Diplodocids. This would have allowed Barosaurus to move very little - if at all - while eating, instead of moving over large distances in search of vegetation.

By Scott Reid

Behavior: Barosaurus was not especially common in its environment, so the question of its social nature is actually somewhat important. Fossil evidence indicates at least some sociality in other Diplodocids - herding, or at least small herds, of other sauropods on the Morrison are clear from fossil evidence and trackways. The question remains - did Barosaurus do what its cousins did? The question is, of course, up in the air without more fossil evidence. It is possible that, in an environment with hundreds and hundreds of large sauropods to feed, Barosaurus may have been more solitary to aid in getting enough food without competing too much with one another. Alternatively, it may have also lived in social groups, allowing for the safety of weaker members of the herd and more cohesiveness in finding food.

Barosaurus, like other Diplodocids, would have been able to rear up on its hind legs to get food. This action would have also made Barosaurus even taller than usual, which would have been fairly imposing to predators nearby. It had a whip-tail, which would have allowed Barosaurus to make very loud sonic cracks in the air; if that tail was covered with spikes, as in other members of the group, it would have also lacerated the skin of other dinosaurs. Still, even without spikes, it would have packed quite a punch for any predators that might have tried to attack it. The sounds of the tail would have been a warning; it is possible that such sounds would have been used in communication with one another, and potentially even display in competition for mates and food and similar things. The impossibly long neck probably was also a sort of sexual display structure, since the longer neck indicated being able to reach more food without walking around. It is uncertain whether or not it would have taken care of its young; while there is no evidence either way - which usually would lead to concluding it did, given the fact most living archosaurs do and there’s extensive evidence of such in extinct dinosaurs - other sauropods (aka the titanosaurs) probably didn’t. So, for now, the jury on that is out.

By Fred Wierum, CC BY-SA 4.0

Ecosystem: Barosaurus lived in the Morrison Formation - an extensive, expansive semi-arid, seasonal floodplain that covered most of Western North America during the Jurassic and was filled with iconic dinosaurs and other animals that we usually think of when we think of the “Jurassic.” Though the Morrison was as arid and open as a modern savanna, the lack of extensive flowering plants at this time rendered the habitat more like a ridiculously huge scrubland. There were a variety of trees - conifers, ginkgos, cycads, and tree ferns - dispersed among the bushes and horsetails and other plants. They congregated around rivers, which were havens of life amongst the arid territory. At the time of the Brushy Basin Environment - the last part of the formation, where Barosaurus could be found - this environment was much muddier and wetter, potentially indicating a change in ecology that would lead to the end of the Morrison Formation, and an extinction of the animals there. There were also expansive volcanic explosions that lead to much of the preservation we see there. A large salt lake present would have been a major feature of the environment, and it was connected to extensive wetlands that formed a break in the wider scrubland around the habitat.

By Danny Cicchetti, CC BY-SA 3.0

Barosaurus may be known from the entire Brushy Basin Environment of the Morrison; however, confirmed fossils of this dinosaur are only known from a few sites. So, in my map above, I give two colors - the wider green color to show the whole ecosystem, aka the wider area that Barosaurus may have ventured in to; and the smaller blue color to show the confirmed range of this dinosaur. In that confirmed range, Barosaurus lived alongside a lot of other animals - in fact, there’s a reason the Morrison is so iconic - its characteristic and distinctive fossils, both of dinosaurs and not of dinosaurs. Barosaurus has been found in, literally, the same sites as other animals - it is known to have lived alongside the predator Allosaurus; in another site, turtles and Pseudosuchians and the Choristodere Cteniogenys, as well as Allosaurus and the more bulky sauropod Camarasaurus; in yet another, Barosaurus lived alongside many turtles, the Pseudosuchians Hoplosuchus and Goniopholis, the tuatara-like Opisthias, and a wide variety of dinosaurs - other sauropods like Diplodocus Apatosaurus and Camarasaurus, predators like Allosaurus Torvosaurus and Ceratosaurus, and Ornithiscians like Stegosaurus Dryosaurus and Uteodon. So, Barosaurus was a part of a very wide and diverse community, with a great diversity in terms of herbivores and predators that would have attacked Barosaurus. That being said, there were many other animals that may have lived alongside Barosaurus, based on just… probability, even though they weren’t found directly with it. There were other stegosaurs like Alcovasaurus and Hesperosaurus; more small running herbivores like Nanosaurus; larger bulky bipedal herbivores like Camptosaurus; more sauropods, including Apatosaurus and Supersaurus; and smaller predators that would have probably been more of a threat to Barosaurus young than adults - Marshosaurus, Coelurus, Ornitholestes, and Stokesosaurus. Sadly, the organization of the Morrison is something of a mess - so, while many other dinosaurs and animals lived alongside Barosaurus, we can’t exactly be sure which ones. There were probably a variety of Multituberculate, Tinodontid, Eutriconodont, and Dryolestoid mammals, as well as others; some pterosaurs were probably there like Harpactognathus, and, of course, there were amphibians as well. This makes the Morrison one of the better examples of an environment to highlight as a representative of a particular time in Earth’s history - since it showcases so many different living things!

By José Carlos Cortés

Other: Barosaurus was a close relative of Diplodocus, though it is difficult to determine how close, as the evolutionary relationships between the Diplodocids are still being worked out via phylogenetic studies. It is possible that an offshoot of Diplodocus (which were around before Barosaurus evolved) split to take advantage of not moving much to eat, and instead sweeping its neck around to gather food. For a while, another sauropod in Africa was considered to be a species of Barosaurus; today, however, it seems to be very clearly in its own genus, Tornieria, and actually far removed from both Diplodocus and Barosaurus (while still being in this closely related family group). So, for now, Barosaurus is only known from North America. These dinosaurs were distinctive long and slender sauropods, as opposed to their long and bulky cousins, the Apatosaurines, that they lived alongside.

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources Under the Cut

Allen, Eric Randall (Summer 2012). "Analysis of North American goniopholidid crocodyliforms in a phylogenetic context.” University of Iowa Research Online.

Apesteguía, S. 2005. Evolution in the hyposphene-hypantrum complex within Sauropoda. In K. Carpenter and V. Tidwell (eds.), Thunder-Lizards: The Sauropodomorph Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press, Bloomington 248-267.

Arldt, T. 1909. Die Dinosaurier [The dinosaurs]. Naturwissenshaftliche Rundschau 24(21):261-263.

Averianov, A. O., and T. Martin (2015). "Ontogeny and taxonomy of Paurodon valens (Mammalia, Cladotheria) from the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of USA" (PDF). Proceedings of the Zoological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences. 319 (3): 326–340.

Berman, D. S., and J. S. McIntosh. 1978. Skull and relationships of the Upper Jurassic sauropod Apatosaurus (Reptilia, Saurischia). Bulletin of Carnegie Museum of Natural History 8:1-35.

Bilbey, S.A. (1998). "Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry - age, stratigraphy and depositional environments". In Carpenter, K.; Chure, D.; and Kirkland, J.I. (eds.) (eds.). The Morrison Formation: An Interdisciplinary Study. Modern Geology 22. Taylor and Francis Group. pp. 87–120.

Bonaparte, J. F. 1986. The early radiation and phylogenetic relationships of the Jurassic sauropod dinosaurs, based on vertebral anatomy. In K. Padian (ed.), The Beginning of the Age of Dinosaurs: Faunal Change Across the Triassic–Jurassic Boundary. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge 247-258

Bonaparte, J. F. 1986. Les dinosaures (Carnosaures, Allosauridés, Sauropodes, Cétosauridés) du Jurassique Moyen de Cerro Cóndor (Chubut, Argentina) [The dinosaurs (carnosaurs, allosaurids, sauropods, cetiosaurids) from the Middle Jurassic of Cerro Cóndor (Chubut, Argentina)]. Annales de Paléontologie (Vert.-Invert.) 72(3):325-386.

Britt, B. B., and B. G. Naylor. 1994. An embryonic Camarasaurus (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation (Dry Mesa Quarry, Colorado). In K. Carpenter, K. F. Hirsch, and J. R. Horner (eds.), Dinosaur Eggs and Babies 256-264.

Butler, R.J., P.M. Galton, L.B. Porro, L.M. Chiappe, D.M. Henderson, and G.M. Erickson. 2009. Lower limits of ornithischian dinosaur body size inferred from a new Upper Jurassic heterodontosaurid from North America. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 10.1098/rspb.2009.1494.

Caldwell, M. W.; Nydam, R. L.; Palci, A.; Apesteguía, S. N. (2015). "The oldest known snakes from the Middle Jurassic-Lower Cretaceous provide insights on snake evolution". Nature Communications. 6: 5996.

Calvo, J. O., and L. Salgado. 1995. Rebbachisaurus tessonei sp. nov. a new Sauropoda from the Albian-Cenomanian of Argentina; new evidence on the origin of the Diplodocidae. GAIA 11:13-33.

Carpenter K & Galton PM (2001). "Othniel Charles Marsh and the Eight-Spiked Stegosaurus". In Carpenter, Kenneth (ed.). The Armored Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press. pp. 76–102.

Carpenter, Kenneth (2006). "Biggest of the big: a critical re-evaluation of the mega-sauropod Amphicoelias fragillimus". In Foster, John R.; Lucas, Spencer G. (eds.). Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, 36. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. pp. 131–138.

Carpenter, K. and Wilson, Y. 2008. A new species of Camptosaurus (Ornithopoda: Dinosauria) from the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic) of Dinosaur National Monument, Utah, and a biomechanical analysis of its forelimb. Annals of the Carnegie Museum 76:227-263.

Carpenter, Kenneth (2018). Maraapunisaurus fragillimus, N.G. (formerly Amphicoelias fragillimus), a basal Rebbachisaurid from the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic) of Colorado. Geology of the Intermountain West. 5: 227–244.

Carrano and Sampson, 2008. The phylogeny of Ceratosauria (Dinosauria: Theropoda). Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 6, 183-236.

Carroll, R. L. 1988. Vertebrate Paleontology and Evolution 1-698

Charig, A. J. 1980. A diplodocid sauropod from the Lower Cretaceous of England. In L. L. Jacobs (ed.), Aspects of Vertebrate History: Essays in Honor of Edwin Harris Colbert. Museum of Northern Arizona Press, Flagstaff 231-244

Chure, 2001. The second record of the African theropod Elaphrosaurus (Dinosauria, Ceratosauria) from the Western Hemisphere. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie Monatshefte. 2001(9).

Chure, Daniel J. (2001). "On the type and referred material of Laelaps trihedrodon Cope 1877 (Dinosauria: Theropoda)". In Tanke, Darren; and Carpenter, Kenneth (eds.) (eds.). Mesozoic Vertebrate Life. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 10–18.

Chure, D. J., R. Litwin, S. T. Hasiotis, E. Evanoff, and K. Carpenter. 2006. The fauna and flora of the Morrison Formation: 2006. In J. R. Foster, S. G. Lucas (eds.), Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 36:233-249

Coombs, W. P., and R. E. Molnar. 1981. Sauropoda (Reptilia, Saurischia) from the Cretaceous of Queensland. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum 20(2):351-373

Curtice, B. D. 1995. A description of the anterior caudal vertebrae of Supersaurus vivianae. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 15(3, suppl.):25A

Dalman, S.G. (2014). "New data on small theropod dinosaurs from the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of Como Bluff, Wyoming, USA". Volumina Jurassica. 12 (2): 181–196.

Demko, Timothy M.; Parrish, Judith T. (1998). "Paleoclimatic setting of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation". In Carpenter, Ken; Chure, Daniel J.; Kirkland, James I. (eds.). The Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation: An Interdisciplinary Study. Modern Geology 22 (1-4): 283-296.

Dodson, P. 1997. American dinosaurs. In P. J. Currie & K. Padian (ed.), Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs 10-13

Ekart, Douglas D.; Cerling, Thure E.; Montanez, Isabel P.; Tabor, Neil J. (1999). "A 400 million year carbon isotope record of pedogenic carbonate; implications for paleoatmospheric carbon dioxide" (PDF). American Journal of Science. 299 (10): 805–827.

Engelmann, George F.; Chure, Daniel J.; Fiorillo, Anthony R. (2004). "The implications of a dry climate for the paleoecology of the fauna of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation". In Turner, Christine E.; Peterson, Fred; Dunagan, Stan P. (eds.). Reconstruction of the Extinct Ecosystem of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. Sedimentary Geology. Sedimentary Geology 167 (3-4): 297-308. 167. pp. 297–308.

Foster, John R. (1996). "Sauropod dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic), Black Hills, South Dakota and Wyoming". Contributions to Geology, University of Wyoming. 31 (1): 1–25.

Foster, J.R. 2003. Paleoecological Analysis of the Vertebrate Fauna of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic), Rocky Mountain Region, U.S.A. Albuquerque, New Mexico: New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science. Bulletin 23.

Foster, J. (2007). "Appendix." Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. Indiana University Press. pp. 327-329.

Foster, J. 2007. Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. Indiana University Press. 389pp.

Foster, J.R. 2009. Preliminary body mass estimates for mammalian genera of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic, North America). PaleoBios 28(3):114-122.

Foster, J. (2018). "A new atoposaurid crocodylomorph from the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic) of Wyoming, USA". Geology of the Intermountain West. 5: 287–295.

Fraas, Eberhard (1908). "Ostafrikanische Dinosaurier". Palaeontographica. 55: 105–144.

Galianom, H., and R. Albersdörfer. 2010. A New Basal Diplodocoid Species, Amphicoelias brontodiplodocus from the Morrison Formation, Big Horn Basin, Wyoming, with Taxonomic Reevaluation of Diplodocus, Apatosaurus, Barosaurus and Other Genera. Dinosauria International (Ten Sleep, WY) Report for September 2010 1-41

Gallina, P. A., and S. Apesteguía. 2005. Cathartesaura anaerobica gen. et sp. nov., a new rebbachisaurid (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the Huincul Formation (Upper Cretaceous), Río Negro, Argentina. Revista del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales, nuevo serie 7(2):153-166

Galton, P. M. 1977. The Upper Jurassic dinosaur Dryosaurus and a Laurasia-Gondwana connection in the Upper Jurassic. Nature 268(5617):230-232

Galton, P.M. & Powell, H.P. (1980). "The ornithischian dinosaur Camptosaurus prestwichii from the Upper Jurassic of England". Palaeontology. 23: 411–443.

Galton, P.M. (1981). Dryosaurus, a hypsilophodontid dinosaur from the Upper Jurassic of North America and Africa. Postcranial skeleton. Palaeontol. Z. 55(3/4), 271-312

Galton, 1982. Elaphrosaurus, an ornithomimid dinosaur from the Upper Jurassic of North America and Africa. Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 56, 265-275.

Galton PM, Upchurch P (2004). "Stegosauria". In Weishampel DB, Dodson P, Osmólska H. The Dinosauria (2nd Edition). University of California Press. p. 361.

Galton, P.M. (2010). "Species of plated dinosaur Stegosaurus (Morrison Formation, Late Jurassic) of western USA: new type species designation needed". Swiss Journal of Geosciences 103 (2): 187–198.

Galton, Peter M. & Carpenter, Kenneth, 2016, "The plated dinosaur Stegosaurus longispinus Gilmore, 1914 (Dinosauria: Ornithischia; Upper Jurassic, western USA), type species of Alcovasaurus n. gen.", Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Abhandlungen 279(2): 185-208.

Gillette, D.D. (1991). "Seismosaurus halli, gen. et sp. nov., a new sauropod dinosaur from the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic/Lower Cretaceous) of New Mexico, USA". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 11 (4): 417–433.

Gilmore, C.W. (1909). "Osteology of the Jurassic reptile Camptosaurus, with a revision of the species of the genus, and descriptions of two new species". Proceedings of the United States National Museum. 36 (1666): 197–332.

Harris, J. D., and P. Dodson. 2004. A new diplodocoid sauropod dinosaur from the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of Montana, USA. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 49(2):197-210

Harris, J. D. 2006. The axial skeleton of the dinosaur Suuwassea emilieae (Sauropoda: Flagellicaudata) from the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of Montana, USA. Palaeontology 49(5):1091-1121.

Hartman, S.; Mickey Mortimer; William R. Wahl; Dean R. Lomax; Jessica Lippincott; David M. Lovelace (2019). "A new paravian dinosaur from the Late Jurassic of North America supports a late acquisition of avian flight". PeerJ. 7: e7247.

Haughton, S. H. 1928. On some reptilian remains from the Dinosaur Beds of Nyasaland. Transactions of the Royal Society of South Africa 16:67-75

Hay, O. P. 1902. Bibliography and Catalogue of the Fossil Vertebrata of North America. Bulletin of the United States Geological Survey 179:1-868

Hendrickx, C, Mateus O. 2014. Torvosaurus gurneyi n. sp., the largest terrestrial predator from Europe, and a proposed terminology of the maxilla anatomy in nonavian theropods, 03. PLoS ONE. 9:e88905., Number 3.

Holtz, Thomas R., Jr.; Molnar, Ralph E.; Currie, Philip J. (2004). Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; Osmólska, Halszka (eds.). The Dinosauria (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 71–110.

Huene, F. v. 1908. Die Dinosaurier der Europäischen Triasformation mit berücksichtigung der Ausseuropäischen vorkommnisse [The dinosaurs of the European Triassic formations with consideration of occurrences outside Europe]. Geologische und Palaeontologische Abhandlungen Suppl. 1(1):1-419

Huene, F. v. 1909. Skizze zu einer Systematik und Stammesgeschichte der Dinosaurier [Sketch of the systematics and origins of the dinosaurs]. Centralblatt für Mineralogie, Geologie und Paläontologie 1909:12-22

Huene, F. v. 1927. Short review of the present knowledge of the Sauropoda. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum 9(1):121-126

Huene, F. v. 1927. Sichtung der Grundlagen der jetzigen Kenntnis der Sauropoden [Sorting through the basis of the current knowledge of sauropods]. Eclogae Geologica Helveticae 20:444-470

Huene, F. v. 1929. Los sauriquios y ornitisquios del Cretáceo argentino. Anales del Museo de La Plata, serie 2 3:1-196

Ibiricu, L. M., G. A. Casal, M. C. Lamanna, R. D. Martínez, J. D. Harris and K. J. Lacovara. 2012. The southernmost records of Rebbachisauridae (Sauropoda: Diplodocoidea), from early Late Cretaceous deposits in central Patagonia. Cretaceous Research 34:220-232

Janensch, W. 1914. Übersicht über die Wirbeltierfauna der Tendaguru-Schichten [Overview of the vertebrate fauna of the Tendaguru beds]. Archiv für Biontologie 3:81-110

Janensch, Werner (1922). "Das Handskelett von Gigantosaurus robustus und Brachiosaurus brancai aus den Tendaguru-Schichten Deutsch-Ostafrikas". Centralblatt für Mineralogie, Geologie und Paläontologie. 1922: 464–480.

Jenkins, J.T. and J.L. Jenkins. 1993. Colorado's Dinosaurs. Denver, Colorado: Colorado Geologic Survey. Special Publication 35.

Joleaud, L. 1922. Les reptiles fossiles [Fossil reptiles]. Association Française pour l'Avancement des Sciences. Conférences. Compte Rendu de la 45e Session 49-66

Kenneth Carpenter; Peter M. Galton (2018). "A photo documentation of bipedal ornithischian dinosaurs from the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation, USA". Geology of the Intermountain West. 5: 167–207.

Kirkland, J. I. 1997. Cedar Mountain Formation. In P. J. Currie & K. Padian (ed.), Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs 98-99.

Kowallis, Bart J.; Christiansen, Eric H.; Deino, Alan L.; Peterson, Fred; Turner, Christine E.; Kunk, Michael J.; Obradovich, John D. (1998). "The age of the Morrison Formation" (PDF). In Carpenter, Ken; Chure, Daniel J.; Kirkland, James I. (eds.). The Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation: An Interdisciplinary Study. Modern Geology 22 (1-4): 235-260.

Ksepka, D. T., and M. A. Norell. 2010. The Illusory Evidence for Asian Brachiosauridae: New Material of Erketu ellisoni and a Phylogenetic Reappraisal of Basal Titanosauriformes. American Museum Novitates 3700:1-27.

Lockley, M.; Harris, J.D.; and Mitchell, L. 2008. "A global overview of pterosaur ichnology: tracksite distribution in space and time." Zitteliana. B28. p. 187-198.

Lovelace, David M.; Hartman, Scott A.; Wahl, William R. (2007). "Morphology of a specimen of Supersaurus (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the Morrison Formation of Wyoming, and a re-evaluation of diplodocid phylogeny". Arquivos do Museu Nacional, Rio de Janeiro. 65 (4): 527–544.

Lucas S, Herne M, Heckert A, Hunt A, and Sullivan R. Reappraisal of Seismosaurus, A Late Jurassic Sauropod Dinosaur from New Mexico. The Geological Society of America, 2004 Denver Annual Meeting (7–10 November 2004).

Lucas, Spencer G.; Spielmann, Justin A.; Rinehart, Larry A.; Heckert, Andrew B; Herne, Matthew C.; Hunt, Adrian P.; Foster, John R.; Sullivan, Robert M. (2006). "Taxonomic status of Seismosaurus hallorum, a Late Jurassic sauropod dinosaur from New Mexico". In Foster, John R.; Lucas, Spencer G. (eds.). Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 36: 149-161.

Lull, R. S. 1919. The sauropod dinosaur Barosaurus Marsh: redescription of the type specimens in the Peabody Museum, Yale University. Memoirs of the Connecticut Academy of Arts and Sciences 6:1-42.

Lull, R. S. 1924. Dinosaurian climatic response. In M. R. Thorpe (ed.), Organic Adaptation to Environment 225-279.

Lydam, R. L., Daniel J. Chure and Susan E. Evans (2013). "Schillerosaurus gen. nov., a replacement name for the lizard genus Schilleria Evans and Chure, 1999 a junior homonym of Schilleria Dahl, 1907" (PDF). Zootaxa. 3734 (1): 99–100.

Madsen, J. H., and W. E. Miller. 1979. the fossil vertebrates of Utah, an annotated bibliography. Brigham Young University Geology Studies 26(4):iii-147

Maidment, Susannah C.R.; Norman, David B.; Barrett, Paul M.; Upchurch, Paul (2008). "Systematics and phylogeny of Stegosauria (Dinosauria: Ornithischia)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 6 (4): 367–407.

Mannion, P. D., P. Upchurch, O. Mateus, R. N. Barnes, and M. E. H. Jones. 2012. New information on the anatomy and systematic position of Dinheirosaurus lourinhanensis (Sauropoda: Diplodocoidea) from the Late Jurassic of Portugal, with a review of European diplodocoids. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 10(3):521-551

Marsh, O. C. 1890. Description of new dinosaurian reptiles. The American Journal of Science, series 3 39:81-86.

Marsh, O. C. 1895. On the affinities and classification of the dinosaurian reptiles. American Journal of Science 50(300):483-498.

Marsh, O. C. 1896. The dinosaurs of North America. United States Geological Survey, 16th Annual Report, 1894-95 55:133-244.

Marsh, O. C. 1898. On the families of sauropodous Dinosauria. Geological Magazine, decade 4 3:157-158.

Marsh, Othniel C. (1899). "Footprints of Jurassic dinosaurs". American Journal of Science. 4 (7): 227–232.

Martin, John. 1987. Mobility and feeding of Cetiosaurus (Saurischia, Sauropoda) – why the long neck? pp. 154–159 in P. J. Currie and E. H. Koster (eds), Fourth Symposium on Mesozoic Terrestrial Ecosystems, Short Papers. Boxtree Books, Drumheller (Alberta). 239 pages.

Mateus, O., & Antunes M. T. 2000. Ceratosaurus sp. (Dinosauria: Theropoda) in the Late Jurassic of Portugal. Abstract volume of the 31st International Geological Congress, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

Mateus, O. 2006. Late Jurassic dinosaurs from the Morrison Formation (USA), the Lourinhã and Alcobaça Formations (Portugal), and the Tendaguru Beds (Tanzania): a comparison. In J. R. Foster, S. G. Lucas (eds.), Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 36:223-231.

Mateus, O. (2007). Notes and review of the ornithischian dinosaurs of Portugal. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 27, 114A-114A., Jan: Society of Vertebrate Paleontology.

Mateus, O., & Tschopp E. (2013). Cathetosaurus as a valid sauropod genus and comparisons with Camarasaurus. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, Program and Abstracts, 2013. 173.

McIntosh, J. S. 1981. Annotated catalogue of the dinosaurs (Reptilia, Archosauria) in the collections of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Bulletin of Carnegie Museum of Natural History 18:1-67.

McIntosh, J. S. 1990. Sauropoda. In D. B. Weishampel, H. Osmólska, and P. Dodson (eds.), The Dinosauria. University of California Press, Berkeley 345-401.

McIntosh, J. S. 1997. Sauropoda. In P. J. Currie & K. Padian (ed.), Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs 654-658.

McIntosh, J. S. 2005. The genus Barosaurus Marsh (Sauropoda, Diplodocidae). In K. Carpenter and V. Tidwell (eds.), Thunder-Lizards: The Sauropodomorph Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press, Bloomington 38-77.

Melstrom, K. M., M. D. D'Emic, D. J. Chure and J. A. Wilson. 2016. A juvenile sauropod dinosaur from the Late Jurassic of Utah, U.S.A., presents further evidence of an avian style air-sac system. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 36(4):e1111898:1-23.

Mezga, A., B. C. Tesovic, and Z. Bajraktarevic. 2007. First record of dinosaurs in the Late Jurassic of the Adriatic-Dinaridic carbonate platform (Croatia). Palaios 22(2):188-199.

Miller, W. E., J. L. Baer, K. L. Stadtman and B. B. Britt. 1991. The Dry Mesa Dinosaur Quarry, Mesa County, Colorado. In W. R. Averett (ed.), Guidebook for Dinosaur Quarries and Tracksites Tour, Western Colorado and Eastern Utah 31-46.

Mocho, P., R. Royo-Torres, and F. Ortega. 2014. Phylogenetic reassessment of Lourinhasaurus alenquerensis, a basal Macronaria (Sauropoda) from the Upper Jurassic of Portugal. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 170:875-916.

Moore, George T.; Hayashida, Darryl N.; Ross, Charles A.; Jacobson, Stephen R. (1992). "Paleoclimate of the Kimmeridgian/Tithonian (Late Jurassic) world: I. Results using a general circulation model". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 93 (3–4): 113–150.

Nopcsa, B. F. 1928. The genera of reptiles. Palaeobiologica 1:163-188.

Olshevsky, G. 1992. A revision of the parainfraclass Archosauria Cope, 1869, excluding the advanced Crocodylia. Mesozoic Meanderings 2:1-268.

Parrish, J.T.; Peterson, F.; Turner, C.E. (2004). "Jurassic "savannah"-plant taphonomy and climate of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic, Western USA)". Sedimentary Geology. 167 (3–4): 137–162.

Pickering, 1995a. Jurassic Park: Unauthorized Jewish Fractals in Philopatry. A Fractal Scaling in Dinosaurology Project, 2nd revised printing. Capitola, California. 478 pp.

Pritchard, A. C.; Turner, A. H.; Allen, E. R.; Norell, M. A. (2013). "Osteology of a North American Goniopholidid (Eutretauranosuchus delfsi) and Palate Evolution in Neosuchia". American Museum Novitates 3783 (3783).

Rauhut, O. W. M., K. Remes, R. Fechner, G. Cladera, and P. Puerta. 2005. Discovery of a short-necked sauropod dinosaur from the Late Jurassic period of Patagonia. Nature 435:670-672.

Remes, K. 2006. A revision of the Tendaguru sauropod dinosaur Tornieria africana (Fraas) and its relevance for sauropod paleobiogeography. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 26(3):651-669.

Remes, K. 2007. A second Gondwanan diplodocid dinosaur from the Upper Jurassic Tendaguru Beds of Tanzania, East Africa. Palaeontology 50(3):653-667.

Romer, A. S. 1956. Osteology of the Reptiles, University of Chicago Press 1-77.

Romer, A. S. 1966. Vertebrate Paleontology, 3rd edition 1-468.

Royo-Torres, R., A. Cobos, A. Aberasturi, E. Espílez, I. Fierro, A. González, L. Luque, L. Mampel, and L. Alcalá. 2007. Riodeva sites (Teruel, Spain) shedding light to European sauropod phylogeny. Geogaceta 41:183-186.

Ruiz-Omeñaca, J. I., L. Piñuela, and J. C. García-Ramos. 2008. Primera evidencia de dinosaurios diplodocinos (Sauropoda: Diplodocidae) en el Jurásico Superior de Asturias (Noreña) [First evidence of diplodocine dinosaurs (Sauropoda: Diplodocidae) in the Upper Jurassic of Asturias (Noreña)]. In J I Ruiz-Omeñaca, L Piñuela and J C García-Ramos (eds), XXIV Jornadas de la Sociedad Española de Paleontología, 15-18 October 2008, Museo del Jurásico de Asturias (MUJA), Colunga, Spain, Libro de Resúmenes 191-192.

Russell, D., P. Beland, and J. McIntosh. 1980. Paleoecology of the dinosaurs of Tendaguru (Tanzania). Mem. Society Geol. France, N.S. 139:169-175.

Russell, D. A. 1984. A check list of the families and genera of North American dinosaurs. Syllogeus 53:1-35.

Saleiro, A., & Mateus O. (2017). Upper Jurassic bonebeds around Ten Sleep, Wyoming, USA: overview and stratigraphy. Abstract book of the XV Encuentro de Jóvenes Investigadores en Paleontología/XV Encontro de Jovens Investigadores em Paleontologia, Lisboa, 428 pp.. 357-361.

Salgado, L. 1993. Comments on Chubutisaurus insignis del Corro (Saurischia, Sauropoda). Ameghiniana 30(3):265-270.

Salgado, L. 1999. The macroevolution of the Diplodocimorpha (Dinosauria; Sauropoda): a developmental model. Ameghiniana 36(2):203-216.

Salgado, L., I. d. S. Carvalho, and A. C. Garrido. 2006. Zapalasaurus bonapartei, un nuevo saurópodo de La Formación La Amarga (Cretacico Inferior), noroeste de Patagonia, Provincia de Neuquén, Argentina [Zapalasaurus bonapartei, a new sauropod from the La Amarga Formation (Lower Cretaceous), northwestern Patagonia, Neuquén province, Argentina]. Géobios 39:695-707.

Schultz, J. A; Bhart-Anjan S. Bhullar; Zhe-Xi Luo (2018). "Re-examination of the Jurassic mammaliaform Docodon victor by computed tomography and occlusal functional analysis". Journal of Mammalian Evolution. in press. doi:10.1007/s10914-017-9418-5.

Seebacher, Frank. (2001). "A new method to calculate allometric length-mass relationships of dinosaurs". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 21 (1): 51–60.

Seeley, Harry G. (1869). Index to the fossil remains of Aves, Ornithosauria and Reptilia, from the Secondary system of strata arranged in the Woodwardian Museum of the University of Cambridge. Cambridge: Deighton, Bell and Co. pp. 143pp.

Sereno, P. C. 1997. The origin and evolution of dinosaurs. Annual Review of Earth and Planetary Sciences 25:435-489.

Smith, David K. (1998). "A morphometric analysis of Allosaurus". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 18 (1): 126–142.

Smith, D. M., M. A. Gorman, J. D. Pardo and B. J. Small. 2011. First fossil Orthoptera from the Jurassic of North America. Journal of Paleontology 85(1):102-105.

Steel, R. 1970. Part 14. Saurischia. Handbuch der Paläoherpetologie/Encyclopedia of Paleoherpetology. Gustav Fischer Verlag, Stuttgart 1-87.

Sternfeld, R. 1911. Zur Nomenklatur der Gattung Gigantosaurus Fraas [On the nomenclature of the genus Gigantosaurus Fraas]. Sitzungsberichte der Gesellschaft Naturforschender Freunde zu Berlin 8:398.

Suteethorn, S., J. Le Loeuff, E. Buffetaut and V. Suteethorn. 2010. Description of topotypes of Phuwiangosaurus sirindhornae, a sauropod from the Sao Khua Formation (Early Cretaceous) of Thailand, and their phylogenetic implications. Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie Abhandlungen 256(1):109-121.

Swinton, W. E. 1970. The Dinosaurs, Wiley-Interscience, New York 1-331.

Tatarinov, L. P. 1964. Nadotryad Dinosauria. Dinozavry [Superorder Dinosauria. Dinosaurs]. In Y. A. Orlov (ed.), Osnovy Paleontologii [Fundamentals of Paleontology] 12:523-589.

Taylor, Michael P; Wedel, Mathew J (2013). "The neck of Barosaurus was not only longer but also wider than those of Diplodocus and other diplodocines". PeerJ. 1: e67v1.

Tidwell, V., Carpenter, K., and Miles, C., 2005, A reexamination of Morosaurus agilis (Sauropoda) from Garden Park, Colorado: Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 25 (Supplement to 3):122A.

Tornier, G. 1913. Reptilia. Paläontologie [Reptilia. Paleontology]. Handwörterbuch der Naturwissenschaften 8:337-376.

Trujillo, K.C.; Chamberlain, K.R.; Strickland, A. (2006). "Oxfordian U/Pb ages from SHRIMP analysis for the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of southeastern Wyoming with implications for biostratigraphic correlations". Geological Society of America Abstracts with Programs. 38 (6): 7.

Tschopp, E., and O. Mateus. 2013. The skull and neck of a new flagellicaudatan sauropod from the Morrison Formation and its implication for the evolution and ontogeny of diplodocid dinosaurs. Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 11(7):853-88.

Tschopp, E., O. Mateus, and R. B. J. Benson. 2015. A specimen-level phylogenetic analysis and taxonomic revision of Diplodocidae (Dinosauria, Sauropoda). PeerJ 3:e857.

Turner, Christine E.; Peterson, Fred (2004). "Reconstruction of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation extinct ecosystem—a synthesis". In Turner, Christine E.; Peterson, Fred; Dunagan, Stan P. (eds.). Reconstruction of the Extinct Ecosystem of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. Sedimentary Geology. Sedimentary Geology 167 (3-4): 309-355.

Upchurch, P. 1995. The evolutionary history of sauropod dinosaurs. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B 349:365-390.

Upchurch, P. 1995. Sauropod phylogeny and palaeoecology. In M. G. Lockley, V. F. dos Santos, C. A. Meyer, & A. P. Hunt (eds.), Aspects of Sauropod Paleobiology. GAIA 10:249-260.

Upchurch, P., P. M. Barrett, and P. Dodson. 2004. Sauropoda. In D. B. Weishampel, H. Osmolska, and P. Dodson (eds.), The Dinosauria (2nd edition). University of California Press, Berkeley 259-322.

von Zittel, K. A. v. 1890. Handbuch der Palaeontologie. I. Abteilung Paleozoologie. III. Band. Vertebrata (Pisces, Amphibia, Reptilia, Aves) [Handbook of Paleontology. Division I. Paleozoology. Volume III. Vertebrata (Pisces, Amphibia, Reptilia, Aves)] xii-900.

von Zittel, K. A. 1911. Grundzüge der Paläontologie (Paläozoologie). II. Abteilung. Vertebrata [Fundamentals of Paleontology (Paleozoology). Section II. Vertebrata]. Druck und Verlag von R. Oldenbourg, München 1-598.

Weishampel, David B.; Dodson, Peter; and Osmólska, Halszka (eds.): The Dinosauria, 2nd, Berkeley: University of California Press. 861 pp.

Whitlock, J. A. 2011. A phylogenetic analysis of Diplodocoidea (Saurischia: Sauropoda). Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 161:872-915.

Wieland, G. R. 1920. The longneck sauropod Barosaurus. Science, New Series 51(1326):528-530.

Wild, Rupert (1991). "Janenschia n. g. robusta (E. Fraas 1908) pro Tornieria robusta (E. Fraas 1908) (Reptilia, Saurischia, Sauropodomorpha)". Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde, Serie B: Geologie und Paläontologie. 173: 1–4.

Wilson, J. A., and M. B. Smith. 1996. New remains of Amphicoelias Cope (Dinosauria: Sauropoda) from the Upper Jurassic of Montana and diplodocoid phylogeny. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 16(3, suppl.):73A.

Wilson, J. A., and P. C. Sereno. 1998. Early evolution and higher-level phylogeny of sauropod dinosaurs. Society of Vertebrate Paleontology Memoir 5. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 18(2 (suppl.)):1-68.

Wilson, J. A. 2002. Sauropod dinosaur phylogeny: critique and cladistic analysis. Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 136:217-276.

Xing, L., T. Miyashita, J. Zhang, D. Li, Y. Te, T. Sekiya, F. Wang and P. J. Currie. 2015. A new sauropod dinosaur from the Late Jurassic of China and the diversity, distribution, and relationships of mamenchisaurids. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 35(1):e889701:1-17.

#Barosaurus lentus#Barosaurus#Dinosaur#Diplodocid#Diplodocoid#Factfile#Palaeoblr#Jurassic#Herbivore#North America#Mesozoic Monday#paleontology#prehistory#prehistoric life#dinosaurs#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature#Sauropod

332 notes

·

View notes

Text

Episode 263: Australia's Largest Dinosaur

I Know Dino Podcast Episode 263: Australia's Largest #Dinosaur, We visit @EromangaNHM to interview Jo Pegler and Corey Richards. Plus a new dinosaur from Japan and an amazing new Miragaia specimen!

Episode 263 is all about Neovenator, an apex predator from the UK with a sensitive face.

We also interview Jo Pegler and Corey Richards, laboratory coordinator and operations & marketing coordinator at the Eronmanga Natural History Museum in southwest Queensland Australia. If you can’t visit them in person, you can see there work at enhm.com.au or on twitter @EromangaNHM

Big thanks to all…

View On WordPress

#3D#Adratiklit#Alcovasaurus#allosauroid#anthophagous#Archeopteryx#australia#avialan#bird#Corey Richards#Cretaceous#Dacentrurine#Dacentrurus#dinosaur#dinosaur of the day#dinosaurs#diplodocids#Eromanga#foliovore#frugivore#Fukuipteryx#genus#granivore#herbivores#i know dino#Jo Pegler#Jurassic#miragaia#museum#Neovenator

0 notes