#allan edwall

Text

"Ronja Rövardotter" (1984) - Tage Danielsson

"February Film Favourites" Day 18/28

Very simply one of the greatest family films ever made. Astrid Lindgren's story has been adapted with immense love and care.

The cast is stellar, the costumes have wonderful attention to historical detail, and the locations showcase the Swedish nature beautifully

Also, no matter how old I get I will always find the wild harpies terrifying!

#February Film Favourites#Ronja Rövardotter#Lena Nyman#Börje Ahlstedt#Hanna Zetterberg#Dan Håfström#Allan Edwall#Per Oscarsson#Tage Danielsson#Astrid Lindgren#family film#Swedish film#Swedish cinema#favourite films#fave films#film GIFs#motionpicturelover's gifs

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

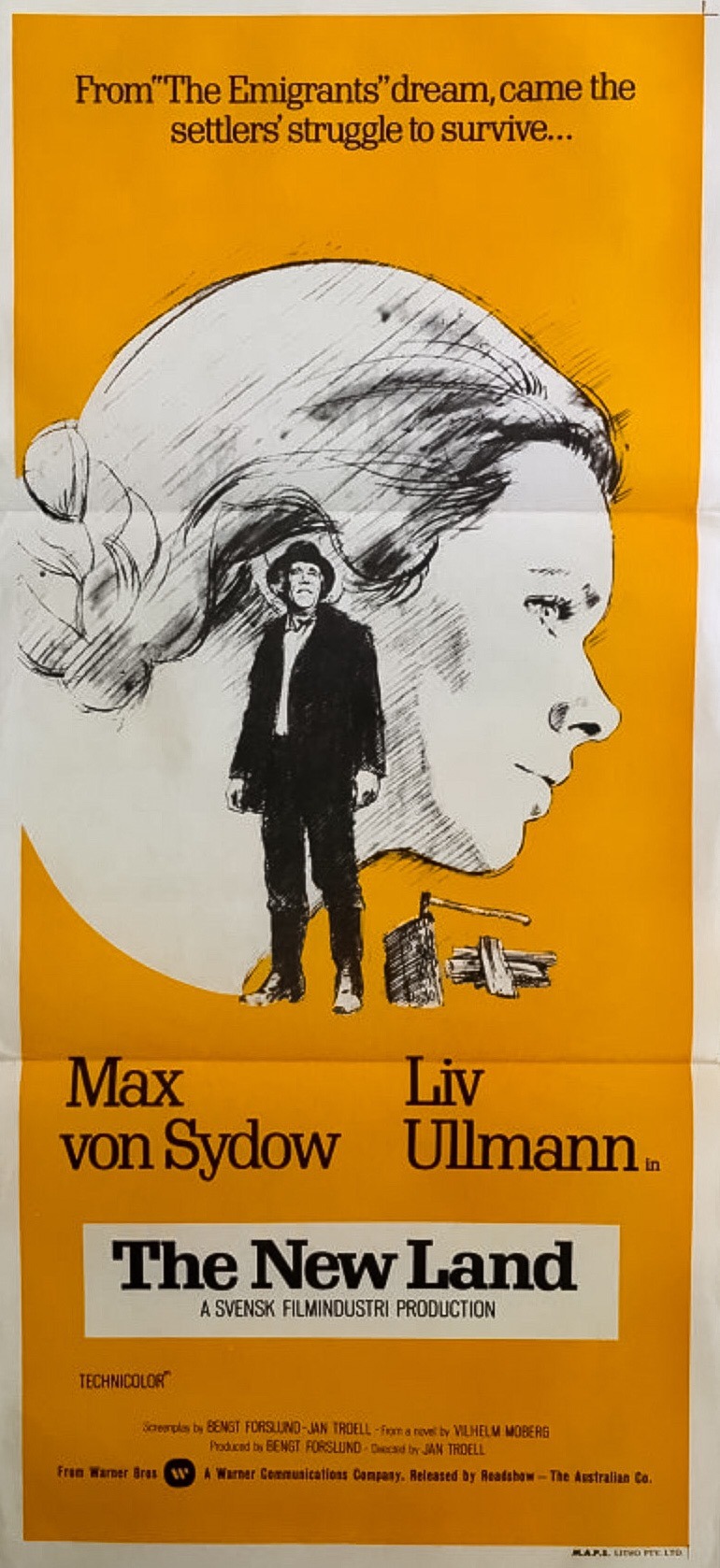

#The Emigrants#Max von Sydow#Liv Ullmann#Eddie Axberg#Allan Edwall#Monica Zetterlund#Pierre Lindstedt#Jan Troell#1971

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

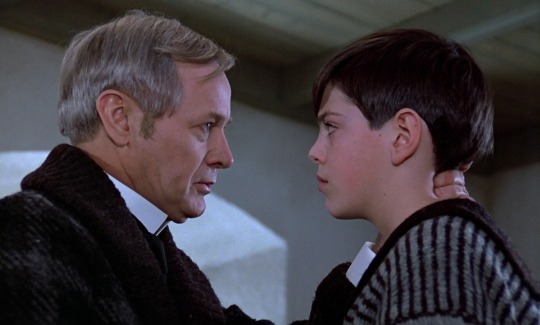

Fanny and Alexander / Fanny och Alexander (1983, Ingmar Bergman)

TV version

12/21-27/23

#Fanny and Alexander#Fanny och Alexander#Ingmar Bergman#Erland Josephson#Gunnar Bjornstrand#Harriet Andersson#Borje Ahlstedt#Ewa Froling#Jan Malmsjo#Allan Edwall#miniseries#TV#Swedish#Sweden#children#Christmas#families#party#turn of the century#middle class#ghosts#child abuse#domestic abuse#theater#actors#coming of age#clergy#stepfamily

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Fanny and Alexander (1984)

#fanny and alexander#ingmar bergman#pernilla allwin#bertil guve#ewa froling#allan edwall#letterboxd#films#tv#motion pictures#cinematography#80s films#80s#movies#cinephile

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Sacrifice. Dir. Andrei Tarkovsky. 1986.

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

sometimes when it's rainy that's really the world telling you to listen to some allan edwall

0 notes

Quote

Att vara en mänska ska mycket till

fast kanske inte så mycket

Det räcker så bra om man bara är

en något sånär acceptabel affär

Och inte en som som blir över,

en sån som ingen behöver

Allan Edwall, Lågkonjunktur

1 note

·

View note

Text

Bertil Guve and Pernilla Allwin in Fanny and Alexander (Ingmar Bergman, 1982)

Cast: Pernilla Allwin, Bertil Guve, Jan Malmsjö, Börje Ahlstedt, Anna Bergman, Gunn Wållgren, Kristina Adolphson, Erland Josephson, Mats Bergman, Jarl Kulle. Screenplay: Ingmar Bergman. Cinematography: Sven Nykvist. Art direction: Anna Asp. Film editing: Sylvia Ingemarsson. Music: Daniel Bell.

Artists' reputations often take a severe hit as time passes: No one thinks Walter Scott was as great a novelist or poet as his contemporaries did; today, he's read only by specialists, and then often grudgingly. So it's not surprising to find people who think that the directors who revolutionized filmmaking in the 1950s and '60s, like Ingmar Bergman, Federico Fellini, and Akira Kurosawa, are mannered and overrated. Some of Bergman's early films, I think, aren't as good as the critics once said: I think, for example, that Smiles of a Summer Night (1955) is better in its incarnation as Stephen Sondheim's A Little Night Music; Wild Strawberries (1957) is a meditation on aging by someone who hasn't aged; The Virgin Spring (1960) strives for a mythic quality that the material and the medium won't bear. But in his later career, after he had ceased to be the darling of the "art houses," he made some intensely personal films that have the warmth and humanity that he could only feint at in the early ones. Critics tend to prefer his films about women, Persona (1966) and Cries & Whispers (1972), but I find him most genuine in his exploration of childhood, especially his elegant reworking of Mozart's The Magic Flute (1975), which sees the opera through childlike eyes, and Fanny and Alexander, which works with a kind of double-vision: We know what's going on in the various sexual combinations and permutations of the Ekdahl family and their lovers, but we also have the point of view of Fanny (Pernilla Allwin) and especially Alexander (Bertil Guve) to elevate them from the merely physical and sometimes sordid into the realm of mystery. If seen from the point of view of the children, this is a kind of ghost story. Alexander will carry into adulthood the experience of seeing two ghosts: one benign, his real father (Allan Edwall), and one malign, his stepfather (Jan Malmsjö). It is also a fable about two kinds of imagination: the artistic and the religious. And we know which side Bergman comes down upon rather heavily.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thanks for tagging me in this babe @goldenkinglouis ❤️

relationship status: happily taken by the person who tagged me ❤️

favorite color: green

song stuck in my head rn: Går det bra? - HOOJA

last song i listened to: Förhoppning - Allan Edwall

three favorite foods: okonomiyaki, pasta with cheese-sauce, baked potatoes with a shit-ton of specific things with that

dream trip: rn USA, it will be Ireland soon

Tagging (no pressure): @seidenbros @gabetheunknown @thequeerlibrarian @toapoet @twistedboxy

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Film #728: ‘Fanny and Alexander’, dir. Ingmar Bergman, 1982.

It's not often I have to start one of these analyses by looking at the question 'What is cinema?' but Ingmar Bergman's filmography is so dense and wide-ranging that it was bound to happen sooner or later. His 1982 magnum opus Fanny and Alexander was originally imagined as a television miniseries and produced in a five-hour version, which was cut down to 188 minutes for a cinematic release. The longer miniseries was released subsequently. According to the book, the version under discussion is the 188-minute cinematic cut, although reading up about the film there are some details from the five-hour version that I think are particularly illuminating. It's arguable that referring to these details (from an extended cut I haven't seen, no less!) is like citing page numbers from Tolkien when talking about Peter Jackson's Hobbit films, but this is my blog, so I'm not going to wade into the reeds on this one.

Anyway, the reason the provenance of Fanny and Alexander feels a little more relevant is because Scandinavia has a rich history of crossover between film and television, with some of its most prominent directors working in television drama production as well as releasing feature films. With the rise of streaming services and prestige television this distinction is a little less important, but to the best of my knowledge Martin Scorsese has never directed an episode of Masterpiece Theater, which is the best analogy I could come up with. Bergman is a director who has clearly given deep thought to the differences between structuring, themes and acting for television and feature film, and the end result is that the three-hour cinematic release feels like three one-hour episodes chained together. The same characters, and an ongoing narrative, but strikingly different themes and tones across each of them.

The first hour introduces our protagonist, Alexander (Bertil Guve), a boy with a feverish imagination. In the first few moments of the film we already see through his eyes a statue moving, and we can get an instant sense of his creativity, but also some of the emotional myopia specific to children - Alexander is withdrawn and distant when he pleases and recklessly dishonest when he pleases, and is constantly blindsided by how others react to his behaviour. This first 'episode' takes place on a busy Christmas Eve as the entire Ekdahl clan gathers at the home of the grandmother Helena (Gunn Wållgren, in her final performance). Helena acts as the emotional centre of the family for the majority of the film, and right from the beginning we often see the other family members considering their own actions in relation to what Helena would think. Some of these characters are drawn in great detail to prepare us for their appearances later: the romance between the married Gustav Adolf (Jarl Kulle) and the family's maid, Maj (Pernilla August) is an ongoing plot, for example. Other characters are carefully drawn, such as Carl, the philosopher, who hates himself for hating his wife, and who only seems happy entertaining the children with his performative farting - but Carl only appears in this section of the film. Bergman is drawing a rich cast of characters that give the world a feeling of population; an intricate web of relationships.

Alexander's father, Oscar (Allan Edwall) gives a rousing Christmas speech to the employees at the theatre he operates, focusing on the differences between the 'little world' of the playhouse and the 'bigger world' outside. He observes that the theatre sometimes succeeds at reflecting the real world, but that the theatre is also an opportunity to escape those real cares - a theme that will be repeated at the end of the film.

Our second episode shifts the focus a little smaller, to the relationship between Alexander and his immediate family. Oscar dies of a stroke while rehearsing the role of the Ghost in Hamlet, and his mother Emelie (Ewa Fröling) is immediately wooed by the local bishop, Edvard (Jan Malmsjö). Emelie immediately learns she has made a mistake when Edvard is strict and controlling towards her and the children, demanding they rid themselves of their possessions and limit their contact with her family. Seemingly out of a mix of retaliation and grief, Alexander's lies and fantasies become more outlandish, culminating in his telling Edvard's maid that he saw the ghosts of Edvard's former wife and children, who announced that Edvard was responsible for their deaths. The maid immediately tells Edvard who, while Emelie is away secretly visiting her family, punishes Alexander and confines him to the attic.

Emelie seeks help from her family, and salvation comes in the form of Isak Jacobi, a local pawnbroker and old flame of Helena. Isak smuggles the children out of the house while Emelie, who is now pregnant with Edvard's child, remains.

The focus is narrowed once more in the third episode, which almost exclusively revolves around Alexander's stay with Isak and his nephews. One is a master puppeteer and the other is a mysterious invalid who seems to have the ability to control the minds and actions of others (I say 'seems' because the film is quite deliberately vague on this point - a decision I'll come back to later). The two nephews either cajole or enable Alexander to bring about the death of the bishop, partially in conjunction with Emelie's decision to heavily sedate her husband so she can leave. The death of the bishop means that Alexander, Fanny and their mother can return to their extended family once more, and the film ends at a lunch celebrating a double christening: Maj's child with Gustav Adolf, and Emelie's child with the deceased Edvard. Gustav Adolf gives a speech which is quite similar to Oscar's in the first hour of the film, extolling the importance of actors in distracting us from life's problems.

The fact that the film opens and closes with similar speeches about the role of theatre in life is telling, because Fanny and Alexander feels like a drawing-room theatre trilogy. Many of the films on the list have drawn their similarities to theatre in an explicit way (think of The Golden Coach, which uses a theatre as a framing device, or Diva, which begins and ends with diegetic opera performances on a stage), but Bergman is working on a slightly more implicit and thematic level. His film is full of literal actors and literal performances, sure, but he also encourages us to think about life through the lens of these performances, rather than just the performances per se.

Here's an example: Oscar's death happens during a rehearsal of Hamlet, in which Oscar is playing the role of the ghost of Hamlet's father. Alexander is in the audience for this rehearsal, and witnesses his father's collapse. The rest of this act plays with the tropes of Hamlet. Alexander is haunted, but not by the ghost of his father (the person who sees Oscar's ghost in this act is Helena). Rather, Bergman uses the trope of 'a ghost attesting to a wrongful death' - Alexander claims to see ghosts who accuse the bishop. A hasty marriage following the death of the protagonist's father is also central to this act, but the causality of it is out of kilter with the narrative being put right in the foreground. Either Bergman, or Alexander, or maybe both, is trying to make life make sense by recycling parts of Shakespeare's play, but none of the pieces quite fit together. At the end of the film, the bishop has been killed, but unlike Hamlet, Alexander stays alive, and the implication instead is that he will forever be haunted by the bishop.

But why should he be? I think it's pretty illuminating from a thematic point of view that at no stage do we really get confirmation of whether the ghosts that Alexander sees are real (at least in this version - in the five-hour version we apparently see the ghosts too, but I can't determine whether we see them in real-time or if they're only show through the frame of a story Alexander tells). The behaviour of the bishop in response to Alexander's accusations is interesting, because Jan Malmsjö plays his role with the menace that makes you believe he could be capable of such a thing. One of three possibilities is true: that the bishop killed his wife and children and the ghosts are real, that the bishop didn't and the ghosts are fictions dreamed up by Alexander, or that Alexander imagines the ghosts and yet has lucked into revealing the truth about the bishop. Bergman doesn't come down strongly on this question, and even the reveal at the end that the bishop's ghost now haunts Alexander doesn't help matters one way or the other. All of these explanations are plausible - either the result of a legitimate haunting or the fevered imagination of a guilt-ridden child.

The same questions arise again when the bishop dies. At least according to what the film tells us is true, the following happens: the bishop's bedridden aunt draws a kerosene lamp closer to her, it topples and sets her alight, and then she fatally injures the heavily-sedated bishop in her attempts to get help. It appears, according to the narrative, that the aunt pulls the lamp closer under the influence of either the puppeteer, who is seen drawing a light closer directly juxtaposed with the aunt doing the same, or under the influence of the other nephew, guiding Alexander to unleash his most destructive psychic impulses. Again, though, both these supernatural explanations are in conflict with the natural explanation.

Whichever of the explanations for these events Bergman wants us to believe is true, it is apparent that these imaginative explanations aren't a lot of help to Alexander: most of the time, in fact, they make things worse. It ultimately doesn't matter too much whether Alexander sees real ghosts or simply imagines them, whether he says so out of childishness or malice: his punishment for claiming to see them is real either way. If Alexander believes himself to be enacting a skewed version of Hamlet's story, the lessons of the play don't benefit him at all. At the end of the film, with the bishop dead (and his death shown in excruciating detail in a flashback), the stories that Bergman uses to try and make sense of the world are shown to be of little help. That brings us back to the speeches that Oscar and Gustav Adolf give, with Gustav Adolf in particular imploring the family, "Don't be sad, dear splendid artists - actors and actresses, we need you all the same. You are there to provide us with supernatural shudders... or even better, our mundane amusements."

What this speech doesn't tell us art and theatre can do is solve problems. It tells us stories of power and the supernatural, but Bergman's film is refreshingly pragmatic when it tells us that art is not powerful or supernatural in itself. It is fiction, and even when it is telling us that amazing things are possible, that doesn't make the amazing things the story depicts any more real than if it said they were impossible.

Fanny and Alexander does seem to have one moment that displays an outright impossible thing. When Isak smuggles the children out of Edvard's house, he hides them in a chest he has offered to purchase from the bishop. He sneaks them into the chest and covers them with a small cloth - clearly too small to adequately hide them. The bishop catches on to Isak's plot, and throws the chest open, but does not see the children inside. He runs upstairs to try and locate them, while Isak falls to his knees and screams in frantic, rageful prayer. Upstairs, Edvard finds the children lying on the floor, still and rigid, but Emilie screams at Edvard not to touch them, and Edvard obeys. The children, apparently still in the chest, are meanwhile snuck out of the house.

What on earth are we to make of this? The film doesn't otherwise give us any reason to believe in the power of God, either from a Christian or Judaic perspective (and it's very difficult to tell if Bergman is drawing on particular strands of Jewish mysticism or just general Semitic stereotypes). I've been influenced here by another blog, Seeing Things Secondhand, whose author is, I believe, an English teacher in the States. Writing about Bergman's work as a whole, he says "God has been uncaring (The Seventh Seal), impotent (The Virgin Spring), terrifying (Through a Glass Darkly), missing (The Silence). Here he is a puppet of man." Isak, and the nephews, Aron and Ismael, evoke God's power to their own ends, and it is always imbued with a hint of menace. After all, if you have access to this type of power, what wouldn't you use it for?

The power Isak and his nephews wield might be real, it might be explained away by a complicated chain of causes, but either way it's not something that the Ekdahl clan has access to. What they have is far more toothless but it is also not tinged with threat at every turn. Isak in particular, straddling the world of the Ekdahls and the world of mysticism, seems like a genial old man who should not be pushed to extremes. In comparison, the rest of the family, as turbulent as their lives are, seem ever-gentle. And that's okay. Their job in the theatre isn't to solve problems, but just to tell us stories.

Fanny and Alexander raises constant interesting questions, then, but the story that it tells across its epic runtime floats, barely tethered, above them. Rick Moody, writing for Criterion and wondering about how autobiographical the film is, suggests that the solution to a film like this is just "to realize that it is the interrogatives of which life is composed. Maybe Fanny and Alexander is simply an autobiographical yarn as Alexander would tell it, so that Bergman and Alexander now appear to us to be one and the same narrator of the tale. Maybe Alexander is Bergman refracted, in this instance in the convex mirror of art, where strange happenstances are routine and tidy answers are hard to come by. Or maybe Bergman is somehow Alexander’s own dream, from which the boy has yet to wake."

That wording resonates with the final scene of the film, in which Emelie presents Helena with the script for the next play the theatre intends to present, August Strindberg's A Dream Play. Sitting down with Alexander resting his head on her knee, Helena begins to read: "Anything can happen. Anything is possible and likely. Time and space do not exist..." It's an oddly comforting conclusion, freeing the characters and the audience from the expectation that anything must be explained. All that needs to happen is for us to watch and to narrate, and life will go on in that gentle way.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s Thomas name day today❤️ I often called him both Allan and Kent-Allan. My mother’s father’s brother is named Allan, or maybe it came from actor Allan Edwall, or maybe it came from poet Edgar Allan Poe. The meaning of the name Allan is handsome/cheerful/little rock - fits Thomas so well🩷

1 note

·

View note

Text

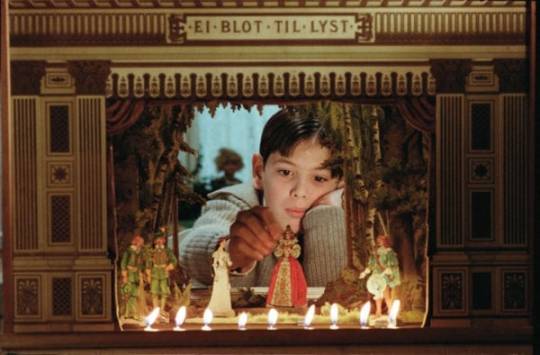

"Ronja Rövardotter" (1984) - Tage Danielsson

(Eng. title: "Ronja the Robber's Daughter")

Films I've watched in 2024 (10/?)

Very simply one of the greatest family films ever made. Astrid Lindgren's story has been adapted with immense love and care.

The cast is stellar, the costumes have wonderful attention to historical detail, and the locations showcase the Swedish nature beautifully.

(Also, no matter how old I get I will always find the wild harpies terrifying!)

Another GIF-set I madefor this film last year.

#films watched in 2024#Ronja Rövardotter#Börje Ahlstedt#Allan Edwall#Tommy Körberg#Lena Nyman#Hannah Zetterberg#Dan Håfström#Per Oscarsson#Astrid Lindgren#Tage Danielsson#fantasy#fantasy film#medieval#medieval fantasy#family film#Swedish film#Swedish cinema#film recommendations#movie recommendation#film gifs#movie gifs#Ronja the Robber's Daughter#motionpicturelover's gifs

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

#The New Land#Max von Sydow#Liv Ullmann#Eddie Axberg#Allan Edwall#Monica Zetterlund#Pierre Lindstedt#Jan Troell#1972

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

0 notes

Text

Analysis of 'The Sacrifice'

The Sacrifice (Offret) is a 1986 Swedish film written and directed by Andrei Tarkovsky. It stars Erland Josephson, with Susan Fleetwood, Allan Edwall, Sven Wollter, and Valérie Mairesse. Many of the crew had worked in Ingmar Bergman films.

The Sacrifice was Tarkovsky’s last film, and his third film as an expatriate from the Soviet Union, after Nostalghia and the documentary, Voyage in Time. He…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Been thinking about good university memories, and I think one of my favourite was one friend commenting"💖Allan Edwall 💖" when he shows up in the opening in Andrei Tarkovsky's film The Sacrifice.

0 notes