#also I really want to learn the gender neutral conjugation of French

Note

ooo i hope art class is going well for you!!! I love Ivy very much, and I do have a pet!!! Her name is Dori :) - 🍄

Dori? Is she a fish? Also thank youuu, art isn’t always my strong suit (I can’t draw people for shit) but I prefer it to some of my other classes for sure *cough* French *cough*

What’s your favorite class/subject currently?

#I just#fuck conjugation#you know?#also I really want to learn the gender neutral conjugation of French#I’m pretty sure there’s a neopronoun set!#anyways#thinking about a bunny that’s dyed royal blue called dori#just: meet my pet dori! she’s really blue!#person: oh! is she a fish?#*a bright blue bunny walks out*#asks#mushroom anon#🍄 anon

0 notes

Note

Bonjour! I’m an American student and I’ve been learning French at school for three years. My French is still iffy, but I’ve been wondering about gender neutral pronouns in French that could be used to refer to a person? I’ve been using il but I wanted to see if there was an alternative, and my searches came up with nothing. Thank you for your time!

Bonjour! I’m going to answer this in English because I want to go into a little bit more detail than I did in my last post about this and I think it’ll be easiest for me to explain in English.

I’ve been using “iel” as a gender neutral pronoun in French, which is a combo of il and elle. I learned about it online and then at my college, my professor and the French language scholars (exchange students from France who also teach conversation classes) said that this would be the best option to use in the same way that one would use they/them/theirs pronouns. However, I’m not sure an average French-speaking person would know about this pronoun, you would probably have to explain it (unless they were really into LGBTQA+ activism or something).

You use iel how you would use any other pronoun, but then there’s a problem with agreement. I’ve seen a lot of people write out both masculine and feminine endings like this:

Il est Américain.

Elle est Américaine.

Iel est Américain.e.

So you separate them with a little dot to have both. Unfortunately, this doesn’t work in speaking because the words just end up sounding feminine. My professor had the students who chose to use “iel” decide whether they wanted their default conjugation and adjective gender to be masculine or feminine. I asked if she could just switch between the two (like use masculine agreement in one sentence, then feminine the next) but she seemed confused by that.

If you want a gender neutral pronoun to use because you don’t know the gender of the person you’re referring to, you could use this one (again, it works just like they/them pronouns in English) but again you’d have the problem with people not knowing what “iel” is. For that it might be best to choose either il or elle as your default or to try to avoid using pronouns (though then you’d have to know the name of the person) or just ask.

Personally, I don’t ask every person I speak to in French to use iel. I’m going to France this summer and I know that’s going to mean a lot of misgendering but I’m okay with it if it makes my journey go smoother (plus, it might be safer). I usually only use iel in class (I got to a very liberal college so I know it’s fine) or online.

Overall, gender neutral pronouns in French are still a work in progress. To have true gender neutrality they’d have to invent not just a new pronoun but also new conjugations and adjective agreements. There’s more about the grammar constraints in this post, written by an actual French person.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

PRONOUN MASTERPOST

This was a request from Jollysunflora so I’ll go through the pronouns in each language in each language from simplest to most complex *cough* Fire-ese *cough*

Earth-ese

In Earth-ese the pronouns are fairly simple. They don’t change for case and are more or less consistent throughout the whole Earth Kingdom. It’s no wonder United Republic-ans chose these over the Fire-ese pronouns.

Jei – 1st-person pronoun: ‘me’, ‘I’

Su – 2nd-person pronoun: ‘you’

Nope – 3rd-person pronoun (pronounced either 1 syllable or 2 syllables depending on the accent). This refers to a human whose gender is either unspecified, unsure, or neither male or female.

Lu – 3rd-person pronoun, used for a female human: ‘she’, ‘her’

Man – 3rd-person pronoun, used for a male human: ‘he’, ‘him’

Ca – 3rd-person pronoun, used for non-humans like: ‘it’

Now, I have left out ‘we’ and ‘they’ here because this is where Earth-ese differs from English a bit, but it’s still fairly simple.

The word-order of Earth-ese actually allows you to put as many pronouns next to each other as you need. So, instead of ‘we’ you either say ‘me and you’ (jei su) or ‘me and you and her’ (jei su lu) or however pronouns describe what you’re referring to.

‘They’ as in a large group of varied people can be ‘Nope lu man’ or ‘man lu’ but in the Southern dialect it is also common to just add the plural suffix ‘-chong’, such as ‘Nopechong’.

For ‘you’ when referring to a large group, Northern Earth-ese speaker would say ‘Su su’ as in ‘you and you’ but in Southern Earth-ese it is more common to say ‘Suchong’.

There are no formal versions of these pronouns as formality and politeness are often added at the start of the sentence with context words in a similar way to ‘please’. Although, in some Southern dialects they suffix these context words onto the pronouns, similar to the plural marker.

UR Fire-ese

I actually lied. UR Fire-ese probably has the easiest pronouns but since they’re derived from the Earth-ese pronouns I thought it was easier to explain those first.

Anyway, UR Fire-ese took ‘Jei’, ‘Su’, ‘Nope’, ‘Lu’, ‘Man’, and ‘Ca’ from Earth-ese but simplified the plural pronouns using the Fire-ese plural suffix ‘-ghan’ (Pronounced ‘-gan’ in the UR). Fire-ese also has a dual suffix (-zu) but since Earth-ese does not it is only used emphatically in UR Fire-ese.

Jeigan – ‘we’, ‘us’

No-pe-gan – ‘they’, ‘them’ (human)

Cagan – ‘they’, ‘them’ (non-human)

While the ‘-ghan’ suffix can be used on any of the other pronouns, these two were the most commonly accepted in general speech. ‘Sugan’ or ‘Suzu’ or ‘Lugan’ are all understood but only really used when you want to be specific, like specifically saying ‘You all’ or ‘the pair of women’.

However, UR Fire-ese is still Fire-ese and the closer you speak to Mainland Fire-ese the ‘posher’ you are perceived. These pronouns are still vastly preferred but a few very posh/formal speakers add Fire-ese pronouns, usually derived from a person’s title, almost like an honorific.

For example, the Council Page Tarrlok sent to convince Korra to join the taskforce. He would say something along the lines of: “Councilman Tarrlok sends his compliments and urges the Avatar to reconsider his offer.”

Despite being a Fire-ese addition, this is often combined with the Earth-ese articles like ‘the’.

Most people make fun of this practice as it sounds like you’re speaking in third person.

Air-ese

Air-ese don’t conjugate for number, gender, or formality so in effect they only have 3 pronouns:

Fa – 1st-person: ‘me’, ‘I’, we’, ‘us’

Ka – 2nd-peron: ‘you’

Ta – 3rd-person: ‘she’, ‘her’, ‘he’, ‘him’, ‘it’, ‘they’

But everything in Air-ese has to conjugate for case to be understood so these are either used as the ‘f-‘, ‘k-‘, and ‘t-‘ prefixes or the ‘-fa’, ‘-ka’, and ‘-ta’ suffixes.

In a noun phrase, you would add ‘(l)ang’ to them: fang/langfa, kang/langka, tang/langta

If the pronoun refers to the subject of a transitive verb (she kicked him), you add a ‘(h)ik’: fik/hikfa, kik/hikka, tik/hikta

Object of a transitive verb (she kicked him), you add a ‘(t)ag’: fag/tagfa, kag/tagka, tag/tagta

Agent of an intransitive verb (she sleeps), you add a ‘(l)in’: fin/linfa, kin/linka, tin/linta

There are other cases which I’ll list in a later post so with Air-ese it is easiest to learn the individual parts and construct them as you go.

Water-ese

Okay, looking at things now I am starting to see a pattern. Why do I hate ‘we’ and ‘them’ so much? Not a single one of my conlangs ended up having a single word for them.

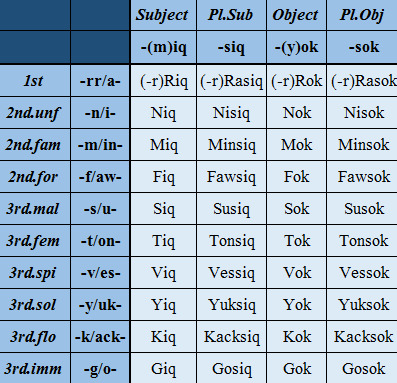

Oh well. Anyway, Northern Water-ese has 10 pronouns, each of which have a plural form, and each of which have a separate form for the subject of the verb and the object of the verb. That equates to…60 forms total. Thank goodness they’re regular! Once again, you just have to learn the basic building blocks and smash them together.

Inside a verb as an indirect object or something similar, they appear as either the onset or the coda listed in the second column e.g. “Nisok kaguroonga giq!”

The verb here is broken down into: [enjoy-hope-3rd.immaterial-present] -> [ka-guroon-g-a] which the ‘-g-’ referring to the immaterial blog which will make happy.

In Water-ese, instead of a formal/informal distinction like French there is a familiar/unfamiliar distinction. The 2nd-person changes depending on how well you know the person, whether they are a stranger or not. Although, there is a formal 2nd-person used for people with a high status.

The 3rd-person pronouns are split into ‘animate’ pronouns and ‘inanimate’ pronouns. You separate humans and animals into either ‘male’ or ‘female’ while spirits have their own 3rd-person pronoun. Everything else is either ‘solid’ – something with a solid form – ‘flowing’ – something physical but changing – or ‘immaterial’ – something without a physical form. These are often compared to the forms of water: ice, water, and steam.

All of these pronouns are used in the Northern Water Tribe but during the separation caused by the 100 Years War the Southern Water Tribe got rid of the animate 3rd-person pronouns and the 2nd-person formal pronoun. This means that in the Southern Water Tribe all humans and animals are described with the ‘solid’ 3rd-person pronoun. Also, in the Northern Water Tribe they refer to the Avatar using the ‘spirit’ 3rd-person pronoun. In the Southern Water Tribe it’s the same ‘solid’ pronoun as other humans.

There are also pronunciation differences between the Northern Water Tribe and the Southern Water Tribe.

NWT: [Rra -> Ra] [Ves -> Fes] [Kack -> Kak]

SWT: [Min -> Moon] [Ves -> Ve] [Yuk -> Yook] [Miq -> Mik]

So ‘Viq’ would be pronounced ‘Fiq’ in the Northern Water Tribe and ‘Vik’ in the Southern Water Tribe.

Fire-ese

Alright, here is the mother of complicated when it comes to pronouns and probably what most of you wanted this post to be about.

There are no regular pronouns in Mainland Fire-ese. Basically, you are constantly speaking in 3rd-person, using things’ names, descriptions, and positions to get across what you are referring to. You can just use people’s names – “Looks like Zuko underestimated the Avatar” – and this is used by children who find remembering pronouns to be difficult but as a result this is often seen as childish or slow-witted.

In an extremely neutral situation, you can use ‘Yudafaw’ or ‘Yukinghan’ to indict yourself who is speaking and the person you are talking to. However, people tend to like to personalise their speech with either their official title, like Fire Lord, or a defining characteristic such as their age, hair, or personality. It is very common to turn adjectives into pronouns like ‘Brown (hair)’, ‘Chatty’, or ‘Blue (clothes)’. These pronouns don’t usually have a specific gender attached to them unless it’s something like ‘mother’, as in the parent who was pregnant, although even this isn’t necessarily female.

These pronouns indicate closeness and formality. For example, most people would refer to the Avatar as ‘Avatar’ (technically ‘Avator’ in the Mainland Fire-ese accent) but once Zuko joins the Gaang and becomes friends with Aang he would instead use ‘Friend’ or just ‘Aang’ in casual conversation.

There is also a good set of demonstratives to refer to inanimate objects:

Uza – Something close to the speaker: ‘this’

Shur – Something close to the listener: ‘this’

(Thing) Lei – Something close to (something): ‘this’

Lian – Something away from the speaker: ‘that’

Mir – Something away from the listener: ‘that’

(Thing) Ehnoz – Something away from (something): ‘that’

‘-zu’ or ‘-ghan’ can be added to any of these to indicate number.

#avatar#the last airbender#atla#lok#legend of korra#conlang#constructed language#air conlang#water conlang#fire conlang#earth conlang#ur fire conlang#answer

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Language Thoughts: Is English Less Formal?

If any of you have lived abroad and learned other languages, it will become quickly apparent that there is a whole lot going on behind language than just basic communication. We use language to show a multitude of qualities about ourselves: our social status, our education, our gender and our closeness with the person we’re speaking to! In French, we have tu (informal singular you) and vous (formal singular and plural you). In Japanese, we have a special verb ending called “-masu” so that taberu (I eat) becomes tabemasu (I politely eat). If you want to be REALLY polite in Japanese, you even use honorific/humble forms of common verbs. taberu would then become meshiagaru (you honorably eat) and itadaku (I humbly partake).

This all sounds so complicated and regular that many English speakers, native and non-native alike, feel perplexed when learning English. To them, English lacks this formality and has become this ultra casual new language where everyone is equal and we don’t have to worry about social hierarchy when speaking, right? WRONG.

English’s Formal “You”

When you read Shakespeare (please God, at least read one Shakespeare play in your life) you will remember that English also had a second form of you, “thou.” This “thou” has become so antiquated and associated with Shakespearean literature, and even GOD in the bible, that people often feel that “thou” was our formal you and we just defaulted to the casual.

But, actually, “thou,” was informal. So, basically, English speakers got tired of accidentally being too casual with each other and decided to just be polite all the time, rather than the other way around. Of course, you doesn’t sound remotely polite or impolite nowadays, but the intent behind the word was to default to politeness, especially when there was no other reason not to. “Thou” and “you” are used nearly identically, aside from a simple difference in conjugation (thou art/thou hast vs. you are/you have).

So English defaulted to the formal, but then how do we then act informal?

Swear Language

English has very colorful swear language. I can’t compare it to all languages, but I know that compared to Japanese, English has dozens more bad words and ways to use those words. Even French just doesn’t seem to have the sheer versatility of English. Just look at “fuck” and all of its meanings and functions in a sentence.

And using swear language can be very rude, but it can also be very casual. While we avoid using swear language at work or with people older than us, many of us use it with our friends and peers. This shows that English speakers are aware of how their language plays into social settings. And, by carefully not using swear language through playful replacement words like “fudge,” or set approved exclamations like “Oh my goodness!” We can move up to a more neutral tone.

But how do we get to politeness?

Formality and Length

What essentially sets formal expressions apart from casual expressions is how much time and thought it takes to say them. For example, when making requests in English, we have multiple levels of formality:

Would you be so kind as to do this for me?

Would you be able to do this for me?

Could you do this for me?

Would you do this for me?

Can you do this for me?

Will you do this for me?

Do this for me?

Do this for me.

Of course, we could also add “please” to all of these phrases to make them even more polite. Clearly, we have a number of different formal levels when speaking, and the person we are speaking to and the value of the request we’re making determines which one is most appropriate. Social status in particular is where I feel English has become most complicated.

What Does “Respect” Mean in English Speaking Cultures?

This is probably what frustrates non-native English speakers the most. I’ll use the U.S. as my example since I’m from there. To the outside eye, it seems like Americans have broken down social hierarchy. Employees are making casual jokes with their boss and students call their professors by their first names. What has happened?

But this is where even Americans have trouble navigating. Social mobility, while not accessible to everyone in the U.S., has become much more common than the days when people were born as rulers or peasants. This means that someone from humble beginnings can believe that he or she will one day be in charge of a lot of people, and may not be altogether comfortable with the shift in language required of them. In fact, casualness can be seen as a form of confident directness. Having the courage to be frank with someone who should intimidate you can actually be admirable, and many people nowadays are recognizing this.

Of course, young Americans are entering a professional culture where they need to be more perspicacious than ever. Not all superiors want to be treated or spoken to as equals, and a young American (a young English speaker) needs to still be able to use formal English, however obscure it might seem.

So the next time one of your friends from abroad makes a jab at English’s casualness, I hope you push them to think more deeply about what formality even means in today’s rapidly changing social structure.

9 notes

·

View notes