#also being dissatisfied with images; trying new things; editing the script...

Photo

10 more images beneath cut:

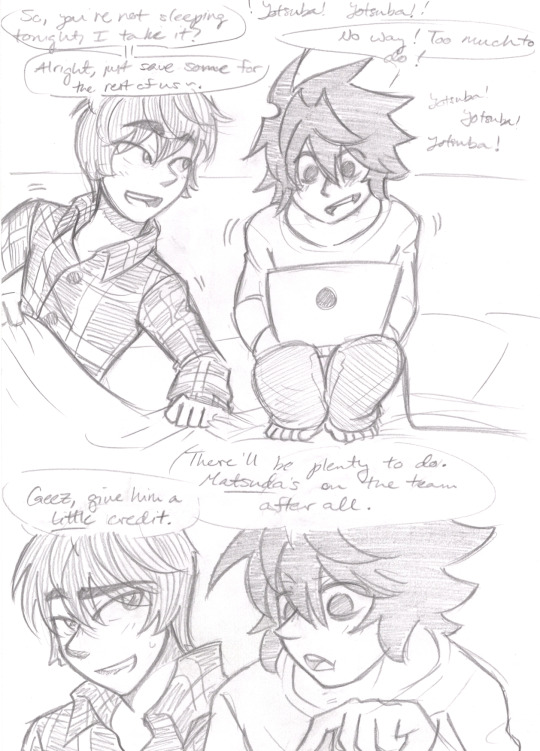

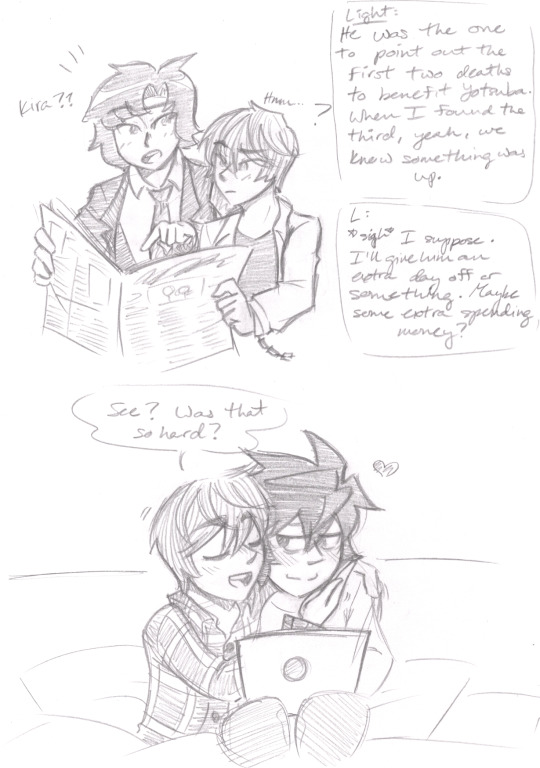

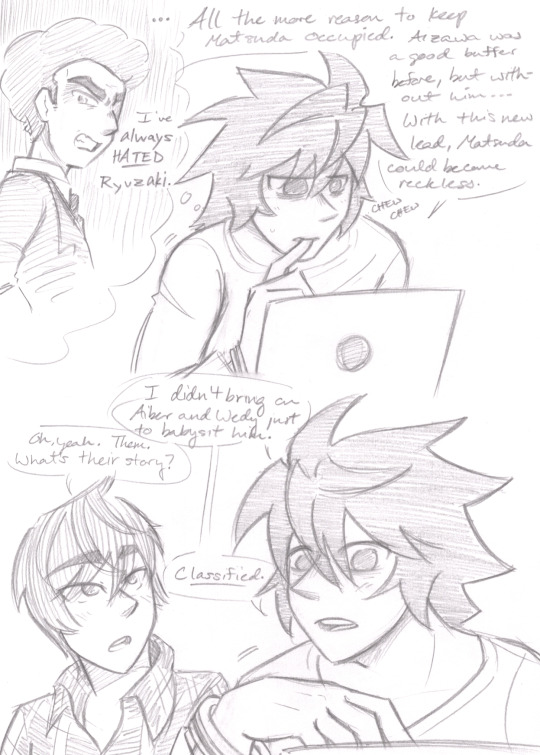

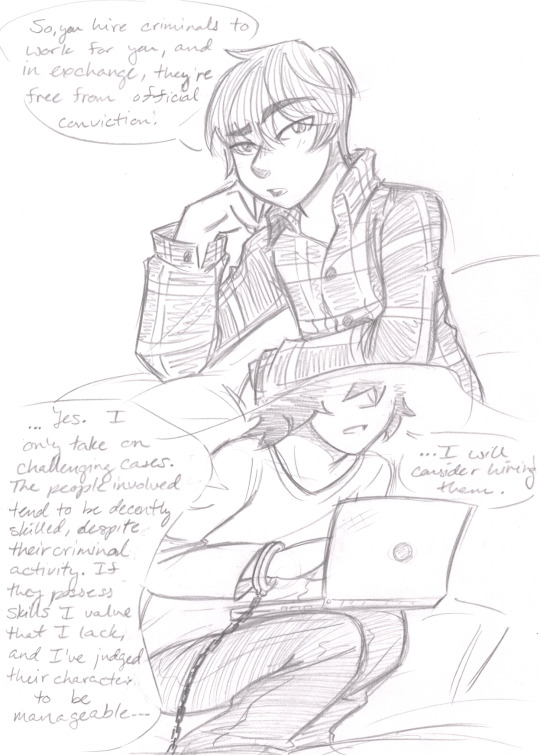

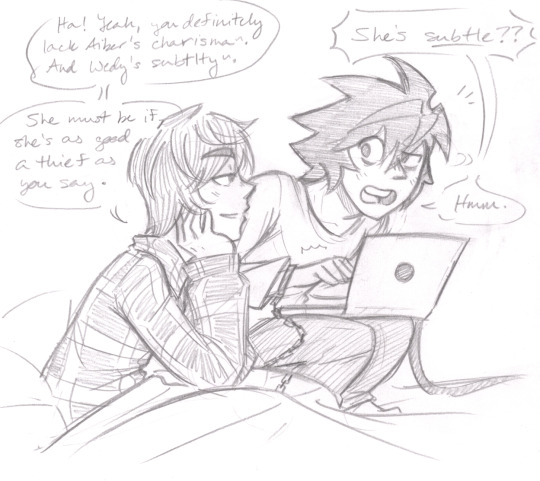

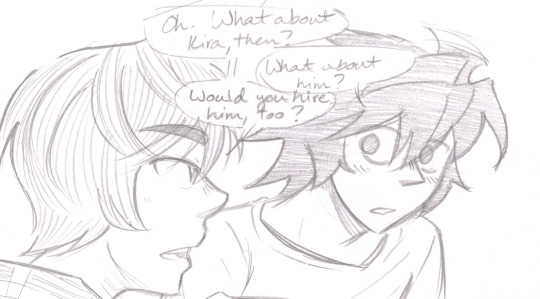

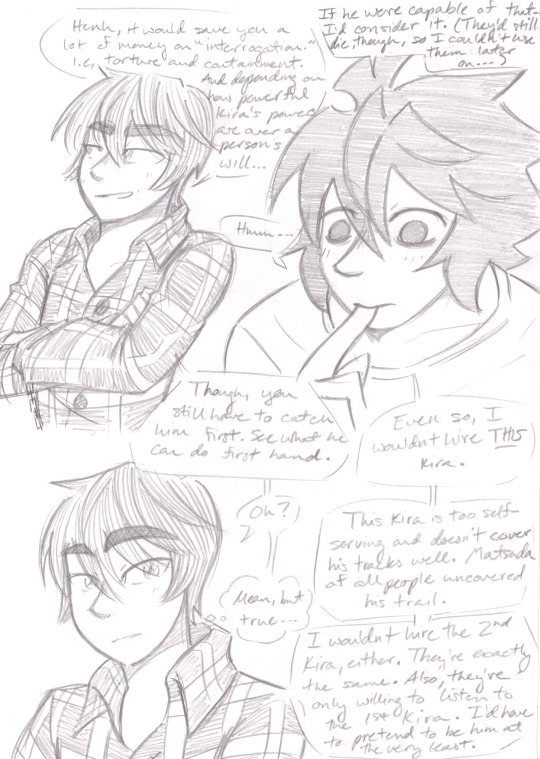

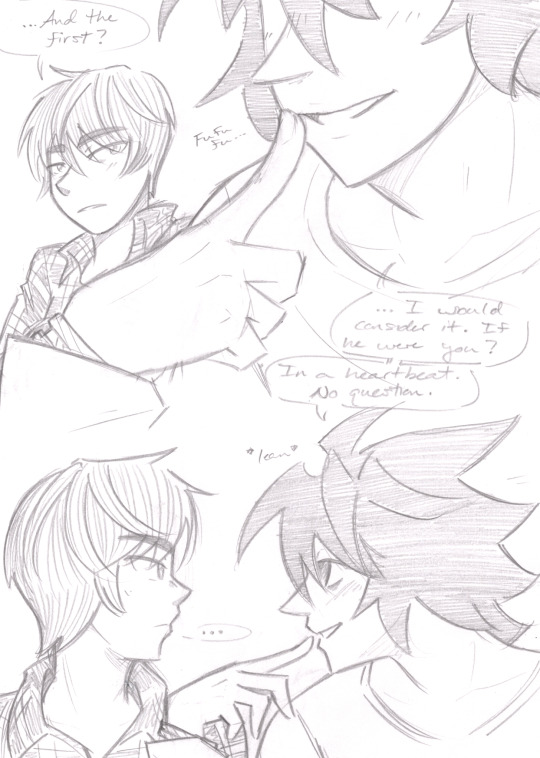

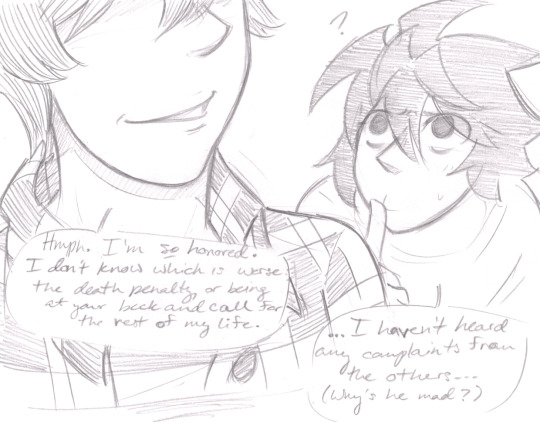

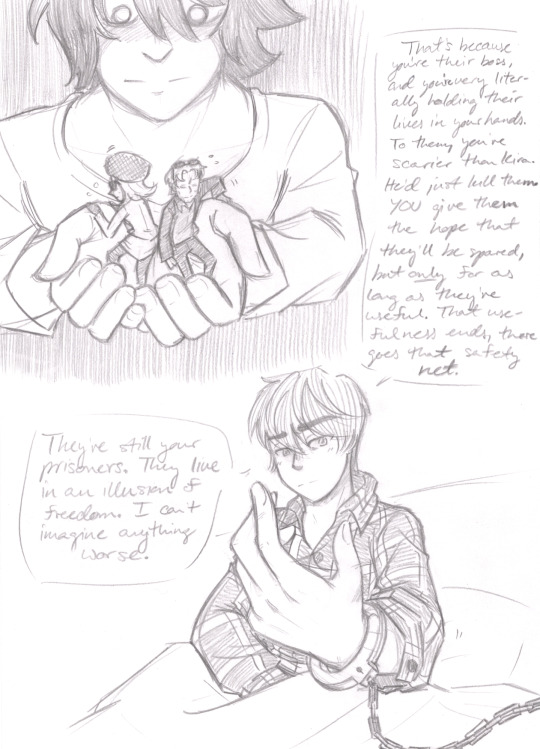

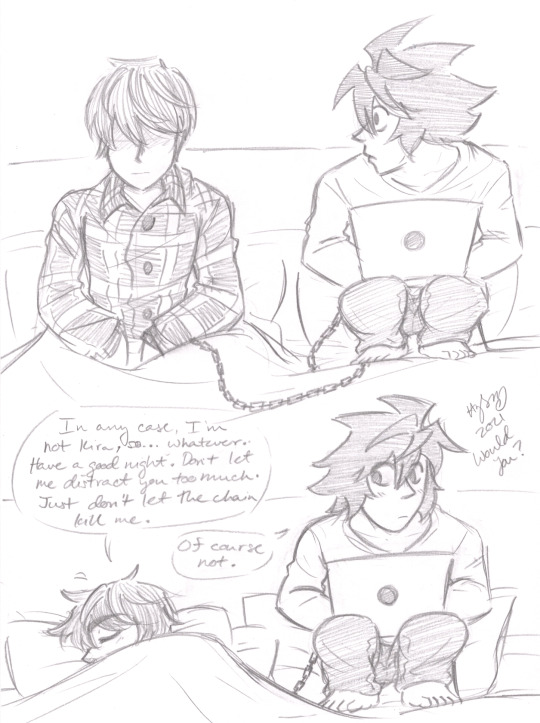

Plot progression! Yotsuba’s tracks are discovered, and L’s hiring techniques are discussed a bit. L kinda tries to flirt, but fails. Light does not want to become part of a collection. He expects that handcuff to come off one day. That wasn’t what L intended inspire, but it set him off. Bonus contemplating image:

He doesn’t get much work done that night (a mixture of feeling defensive, indignant, and just... bad in general for accidentally upsetting Light and souring the evening).

Previous

Next

First

Master List

Transcript

Also, some explanations:

I’m following manga canon here in regards to how they found Yotsuba’s Kira activity. There, Matsuda kept chiming in with “I helped, too.” I’m headcanoning that he really did help by pointing out a couple deaths Yotsuba benefited from (probably from a gossip section) that Light wrote off as coincidence but kept in the back of his mind. Light didn’t actually say anything about Matsuda’s aid onscreen, but I have him give him credit in this private moment. That’s the form I’d imagine Matsuda’s help would come in. He seemed like the media guy on the Task Force~. In the anime, he gave Light all the credit, claiming he “doesn’t know how he did it.” I was reading the scene in the manga, and that stuck more (I watched that episode mainly for Aizawa’s blow-up~).

I took some liberties with L’s employer/employee relationship with Aiber and Wedy. It was probably not as “doom and gloom” as I’ve portrayed here since they seemed pretty casual with L (Aiber asking permission to scam more money out of Yotsuba [manga], Wedy backtalking about having to abandon her work on other places to focus on just Higuchi...). Though, this was from Light’s perspective, and it didn’t seem like a very glamorous life to him, seeing how he was already physically tethered to L (even if he does like him a bit here). Aiber and Wedy had to have been fully aware of the power L had over them, and they were just making the best of it. It was better than rotting in jail and/or getting killed by Kira (lol Aiber said this himself~). Henh, this was probably super obvious, but the series only implied it. I have other thoughts on their relationship, but this description is too long as it is.

#drawn by me#my fanart#my fancomic#The Chain#Death Note#Light Yagami#L#Touta Matsuda#Shuichi Aizawa#Wedy#Aiber#Merrie Kenwood#Mary Kenwood#Thierry Morello#lawlight#henh sorry this one's kind of a downer~#and it has some nerding in it#my style is so inconsistent... you can TELL I did this over the stretch of days#also being dissatisfied with images; trying new things; editing the script...#time moves forward#Yotsuba Arc#it officially begins#I like giving L glowy eyes~#L as an 'employer' of criminals#what Light doesn't want#I almost posted this sooner but then realized I hated some panels and had to redraw them#my perspective needs work#should probably start elaborating on what he DOES want (does HE even know though? he's not devoting full brain power to this topic)#(more important things right now; like proving he's not Kira)#long post

401 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Revolution That Wasn’t – Law & Liberty

Twenty years ago, we saw the lightning flash of The Matrix, an entirely new form of action movie for American audiences. It combined science fiction with noir, mixing in Japanese apocalyptic manga/anime and Chinese fight choreography, hinting at post-modern intellectual pursuits—all of this wrapped up in impressive new cinematic technologies. The movie seemed destined to change movie-making and won four Oscars, mostly in sound and visual effects, but also the very important editing award.

This turned out to be all lightning and no thunder. Cinema didn’t really change and pretty much all the movies that imitated The Matrix failed and have been forgotten. The Matrix was only the 5th highest grossing movie of 1999 with $171 million in America, and $463 million worldwide. The franchise as a whole proved to be both commercially and artistically disappointing.

The Matrix appeared to combine all four ambitions of avant-garde modern art: Intellectualism, visual technology, music, and political revolution.

That the Wachowskis set out to make an intellectual kind of action film is striking because it defies the conventions of the genre. Indeed, before shooting the movie the writer-directors had the cast read one of the important works of postmodern thought, Jean Baudrillard’s 1981 Simulacra and Simulations, and they placed the book prominently in the movie itself. They even had a major character quote from its famous opening: Welcome to the desert of the real. This, of course, suggested a radical criticism of prevailing conditions and social arrangements.

Next, the Wachowskis availed themselves of new technologies. The hope was that film would redefine itself in the digital age as the only adequate representation of our quest for self-understanding, fully employing the powers of visual effects. What society makes invisible or even unthinkable—our very imaginations—could now be adequately represented on the screen. The Matrix works with the premise that technology might fulfill its ultra-modern purpose, to make man fully malleable by computerizing our experience.

Music would then provide the animating power necessary to connect the people—indeed, mankind as such—to the ideas of revolution. From Marilyn Manson to Rage Against The Machine to any number of forgettable angry urban youth bands to club music—The Matrix was supposed to be subversive, transgressive, popular, and futuristic all at once.

This was all intended to add up to political revolution. Like my friend Pete Spiliakos says, Matrix is a Marxist awakening story. Everyman hero Neo (Keanu Reeves) lives a banal and dissatisfying life in a modern metropolis, replete with corporate cubicle work, and he thinks that’s what freedom is. Then he learns that what he takes to be capitalist democracy is in fact the worst form of slavery known to history, since it has enslaved not merely the body but the mind as well. Then Neo awakens to fight the capitalist oppressors!

But there’s something off here: Is a singular hero required to fulfill the Marxist fantasy of destroying the oppressors? Well, if he’s just an everyman, then we’d all have solved our political problems by now. And if he’s only able to accomplish this with magic, as Neo does, that’s no solution at all.

The story has a double character: it depicts an unremittingly grim political situation alongside the promise of great personal power. The class conflict has men fighting machines in a distant future where technology has erased human freedom and, indeed, become a new god that demands the ongoing sacrifice of our bodies and minds. Our wildest expectations about Progress are overwhelmed! In accordance with Marx, the machine proves to be the agent of the revolution—technology is real, ideology is fake. But the dream of Progress turns into a nightmare because human beings are stuck being human and therefore an inferior being.

There’s no denying the inferiority, but then there’s no accepting it, either. To be human is to be perplexed: Keanu asks questions all the time and seems surprisingly dim-witted. Human beings are limited by their bodies in a way the machines are not and the human form of freedom, imagining a world unlike the real world, is itself turned against them by the machines. Everyone ends up trapped in an illusion, because it beats the miserable reality of their enslaved mortal bodies. In the case of Cypher (Joe Pantoliano), we find a character who consciously chooses slavery of body and a pleasant illusion for the mind, the nearly universal condition in this technological tyranny. Therefore, liberating those bodies becomes imperative. Freedom to be who we really are, turns out conveniently to coincide with the fight for survival. There is no difference between mere life and the good life here. So the personal situation turns out to be much better than the political situation—mankind may become extinct, but Neo and his fellow rebels can explore their identities and acquire shocking powers in the process, albeit only when they reconnect themselves to the Matrix.

The film tells an important truth: Nothing can make people content to be as they are—nothing stops them from imagining things that might be better. And in the Matrix, such self-transformation is limited only by one’s imagination and ability to manipulate the system.

This is how the Marxist uprising against capitalism turns into the wonders of gender-bending. The only strangely prophetic thing about this movie was the androgynous romance where you had to try hard to tell Neo apart from Trinity (Carrie-Anne Moss). This is, of course, the story of the writer-directors, the Wachowskis, who were two brothers when they made this movie and are now two sisters. Discontent with the world becomes most personal in discontent with the body which, since it is not chosen, is not part of one’s identity, but part of the given world. Radical liberation is not just liberation of bodies, but liberation from the human body itself.

The movie also formulates an idea that doesn’t fit the excitement of magical powers and a Marxist uprising. It implies that the engine of history isn’t violence or power. Desire drives us: Human freedom is driven by eros, and the demand of eros is for fulfillment and completion. But the characters don’t live in a world defined by human nature or its limits. Every limit is thus overcome and the power of chance is ultimately conquered, which is of course the modern project. In a dark world like Matrix, this leads to the negation of ordinary human life itself: hence androgyny, hence adding machine powers to human powers, hence adding virtual reality to disappointments of everyday life.

This story, which fascinated so many people, failed because it shares the modern aversion to tragedy and therefore offers a strangely flat image of humanity. You cannot take seriously the struggles of those fated to win. Moreover, the writer-directors didn’t have the courage of even following their main idea and putting an unchained eros at the core of being human.

The Wachowskis suggest through The Matrix that, deeper than the political conflicts obvious already in the late 90s, individualism made people feel deeply wounded—radically incomplete, unable to be human merely by themselves, but also unable, given their search for something or someone to complete them—to dedicate themselves to any political community. Bold ideas became necessary just to get by. The Wachowskis wagered that fantastic identities would get people to act when politics wouldn’t. Mythology, not ideology, would create a perfect human-machine combination, but this hasn’t quite come to pass.

Through the film’s characters, the Wachowskis suggest that the human body might be ruled by the most demanding and ambitious desires imaginable, by tyrannic dreams we enact while awake. Our bodies make us mortal and unwise. We’re stuck chasing things we cannot have—immortality, perfection. Power encourages our delusions; it does not offer a cure. Only the power to radically alter the body and free ourselves from our bodily limitations could fix our pained awareness of incompleteness.

Politics on the basis of absolute individualism ultimately involves a desire to do violence to oneself to achieve a fullness that politics itself can never provide. This was the darkest, most dangerous suggestion of the Wachowskis, and the one we are seeing play out today.

!function(f,b,e,v,n,t,s)if(f.fbq)return;n=f.fbq=function()n.callMethod? n.callMethod.apply(n,arguments):n.queue.push(arguments);if(!f._fbq)f._fbq=n; n.push=n;n.loaded=!0;n.version='2.0';n.queue=[];t=b.createElement(e);t.async=!0; t.src=v;s=b.getElementsByTagName(e)[0];s.parentNode.insertBefore(t,s)(window, document,'script','https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/fbevents.js'); (function(d, s, id) var js, fjs = d.getElementsByTagName(s)[0]; if (d.getElementById(id)) return; js = d.createElement(s); js.id = id; js.src = "http://connect.facebook.net/en_US/sdk.js#xfbml=1&version=v2.5"; fjs.parentNode.insertBefore(js, fjs); (document, "script", "facebook-jssdk"));

The post The Revolution That Wasn’t – Law & Liberty appeared first on NEWS - EVENTS - LEGAL.

source https://dangkynhanhieusanpham.com/the-revolution-that-wasnt-law-liberty/

0 notes

Link

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({});

Ars readers likely recognize a few of these faces on the poster for The Toys That Made Us.

Netflix

Volk-Weiss and his team went straight to the source, as you can see these original notes from Kenner on their famed Star Wars toy line…

Early X-Wing sketch from Kenner!

Early everyone sketches from Kenner, too!

Naturally, the popularity of space toys encouraged a few corporate marketing spin-offs…

Creator Volk-Weiss has a soft spot for Star Trek, having directed a 50th anniversary documentary for The History Channel. The series has teased Trek toys will be coming into focus in the spring…

Brian Volk-Weiss has seen his share of documentaries. Heck, he’s even made a few, including a two-hour documentary going where no one has gone before (specifically, the History Channel’s 50 Years of Star Trek). But when the longtime TV producer first approached Netflix with an idea near and dear to his heart, it didn’t exactly cut through the clutter.

Previously, the only work Volk-Weiss had done for the streaming company were comedy specials centered on everyone from Jim Gaffigan to Tiffany Haddish. But he’d been sitting on a pitch about an even older passion—his 30+ years of collecting toys.

“For a long time, I kept annoying [Netflix] about what they kept calling, ‘Brian’s Toy Show,’” he tells Ars. “Eventually, I was lucky enough to get someone to listen and take me seriously.”

If the History Channel connection didn’t give it away, Volk-Weiss loves a good backstory. “Brian’s Toy Show” started from a few Internet deep dives when he came away dissatisfied with the lack of origin story information on iconic toys from Barbie to He-Man. But Netflix—contrary to the hands-off reputation the “network” has gained with its high-profile originals—gave Volk-Weiss a bit of honest feedback. That feedback ended up saving “Brian’s Toy Show” and eventually shaping it into the delightful, recently released docu-series The Toys That Made Us.

“They said, ‘We trust that you’re a nerd about toys, but if you make a show only for people like you, you’re going to have 30 people watching it,’” Volk-Weiss recalls. “‘We don’t greenlight shows for 30 people.’”

So, instead of a serious historical project Ken Burns could love, Volk-Weiss embraced what he knew: comedy. And now that I have finally caught up on the four episodes that debuted this winter, I can declare that this tweak frankly makes the whole thing.

Enlarge / Brian Volk-Weiss (right) presents with Craig Ferguson ahead of their History Channel project.

A doc for those raised on Saturday morning cartoons

To be clear, The Toys That Made Us has no shortage of information. Volk-Weiss and his team get practically every designer and exec you could ask for on camera, despite dealing with major brands like Hasbro, Kenner, and Mattel. The first four episodes cover Barbie, He-Man, and G.I. Joe, while George Lucas ends up being the only “so-and-so declined to appear” slide throughout. Even if that disappointed Volk-Weiss, he’s quick to note how rare his access was and how interesting all the minds behind these toys turned out to be.

“Listen, sitting there meeting the dude who sculpted the original Tie-Fighter model was way more exciting ahead of time than it was to meet the woman who figured out what Barbie’s hands would look like,” Volk-Weiss says regarding access (and revealing Star Wars as his preferred brand of toy obsession). “But after I understood what Barbie was, I’m now more interested in Barbie than many things—but nothing will ever dethrone Star Wars.’

With that trove of information, however, Volk-Weiss leaves room for his documentary to have a sense of humor. The He-Man episode does not shy away from how many of the side characters—like villain Stinkor or hero Ram Man—seem like split-second ideas and naming decisions. A G.I. Joe creator’s insistence on his toy being “an action figure, not a doll” gets turned into a running soundbite joke throughout that hour. And almost unthinkable ideas in retrospect—from the Heinz Burger Blaster to the puberty-themed Growing Up Skipper—get proper acknowledgment and roasting. You’ll chuckle regardless of fandom, but even diehards of a certain toy line seem to walk away with new revelations.

“The biggest surprise for me—because the truth was the exact opposite of what I spent my life believing, and it felt like 98 percent of people my age felt the same way—we all grew up thinking George Lucas made 99 cents out of every dollar from the toys,” Volk-Weiss says. “And I remember reading the transcripts from the field producers and hearing George Lucas only got 2.5 percent. I said, ‘No, no, that’s wrong. That’s not true, you misheard him. That’s wrong.’”

(#NoSpoilers, but let’s say Lucas didn’t make as lucrative of a deal as Star Wars fans assumed. This discovery definitely made Internet headlines for the documentary.)

Where else do you turn for life lessons? Television inspired by toys, duh.

The Toys That Made Us also (inadvertently, it turns out) does a smart thing and borrows its format from the TV spinoffs associated with the very toys being analyzed. Each episode includes an animated title sequence with a Saturday morning cartoons-ish jingle near the start. All the toys have genuine moments of conflict involved—He-Man execs trying to sell what’s essentially marketing research by promising comics or TV on the spot; Barbie’s on-point leadership being ruthless and fast-tracking concepts to market to usurp things like Jem or Bratz; etc.—throughout the middle. And all the episodes end with those signature life lessons-ish post-scripts you’d see on G.I. Joe or He-Man. This is when The Toys That Made Us encapsulates a given toy’s lasting impact in the face of any do-or-die moments overcome.

“Actually, I learned the importance of a good ending from early Jackie Chan movies,” Volk-Weiss admits, citing how Chan would play funny outtakes over his films’ credits. “Even if you sat there for an hour and a half kinda bored, you watch these brilliant outtakes and leave the theater laughing and smiling about how great the movie was.”

(To drive home this storytelling philosophy: Volk-Weiss says hundreds and hundreds of hours went into each episode, but he knows he spent at least 11 hours in the editing bay on just the last five minutes of the Barbie episode, for instance.)

The Toys That Made Us docu-series has four more episodes in the works focusing on Hello Kitty, Transformers, LEGO, and Star Trek. They’ll be available on Netflix sometime in the first half of 2018 (Volk-Weiss was still in production and didn’t have a firm release date to share when speaking with Ars).

While no second season has been announced yet, Volk-Weiss is confident he has oodles of additional material if Netflix wants to move forward. He says the reaction has been extremely positive from both collectors and non-collectors, and plenty of fans have been reaching out to him about plenty of other toys—Hot Wheels, Power Rangers, WWF figures.

“If I’m ever found dead in a ditch at some con, ask the president of the My Little Pony fan club for an alibi,” he jokes. But if things do move forward, there’s a clear first episode for any hypothetical season two.

“Turtles [as in Teenage Mutant Ninja], without a doubt, is what people asked about the most,” Volk-Weiss says. “People were repeatedly asking me, ‘Why would you do a Star Trek episode and not a Turtles? I’m pretty sure if I was watching the show I’d be wondering that, but I did Star Trek because I love Star Trek. I didn’t know if I’d get more episodes, and I wanted to do Star Trek.”

Listing image by Netflix / The Toys That Made Us

http://platform.twitter.com/widgets.js

(adsbygoogle = window.adsbygoogle || []).push({}); http://ift.tt/2BoKOHf February 11, 2018 at 09:04PM

0 notes