#amerian

Text

#mercury#Marauder#mercury marauder#classic#history#historic#classic car#ford#ford history#mercury history#amerian#american car#49 merc#merc#mercury 1949#coupe#custom#kustom#staletto#stilleto#hotroad#hot road

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Charles Ethan Porter (1847-1923)

"Untitled (Cracked Watermelon)" (c. 1890)

Oil on canvas

Located in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York City, New York, United States

Porter was among the first African American artists to exhibit his work nationally and the only one to specialize in still lifes. The painting's subject—originally an African gourd brought to the New World by seventeenth-century Spaniards and cultivated by colonists—is significant. Porter chose to paint a watermelon, an earlier symbol of American abundance—and during the Civil War period one particularly associated with free Blacks—when it was increasingly defined by virulent stereotyping. By reclaiming the subject in artistic terms, Porter challenged a contemporary racist trope.

#paintings#art#artwork#still life painting#watermelon#charles ethan porter#oil on canvas#fine art#the metropolitan museum of art#the met#museum#art gallery#american artist#african amerian artist#black artists#history#art analysis#freedom#fruit#fruits#food#1890s#late 1800s#late 19th century

818 notes

·

View notes

Text

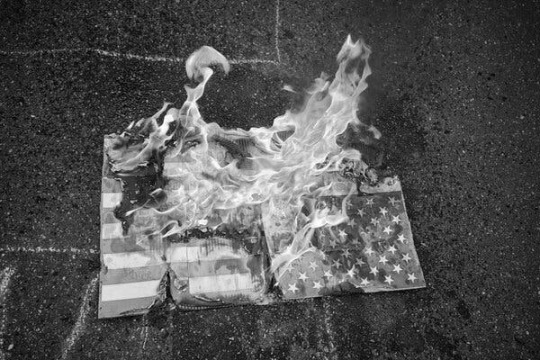

One Single Day. That’s All It Took for the World to Look Away From Us

This article is part of a collection on the events of Jan. 6, one year later. Read more in a note from Times Opinion’s politics editor Ezekiel Kweku in our Opinion Today newsletter.

The Jan. 6 attack on Congress by a mob inspired by former President Donald Trump marked an ominous precedent for U.S. politics. Not since the Civil War had the country failed to effect a peaceful transfer of power, and no previous candidate purposefully contested an election’s results in the face of broad evidence that it was free and fair.

The event continues to reverberate in American politics — but its impact is not just domestic. It has also had a large impact internationally and signals a significant decline in American global power and influence.

Jan. 6 needs to be seen against the backdrop of the broader global crisis of liberal democracy. According to Freedom House’s 2021 Freedom in the World report, democracy has been in decline for 15 straight years, with some of the largest setbacks coming in the world’s two largest democracies, the United States and India. Since that report was issued, coups took place in Myanmar, Tunisia and Sudan, countries that had previously taken promising steps toward democracy.

The world had experienced a huge expansion in the number of democracies, from around 35 in the early 1970s to well over 110 by the time of the 2008 financial crisis. The United States was critical to what was labeled the “Third Wave” of democratization. America provided security to democratic allies in Europe and East Asia, and presided over an increasingly integrated global economy that quadrupled its output in that same period.

But global democracy was underpinned by the success and durability of democracy in the United States itself — what the political scientist Joseph Nye labels its “soft power.” People around the world looked up to America’s example as one they sought to emulate, from the students in Tiananmen Square in 1989 to the protesters leading the “color revolutions” in Europe and the Middle East in subsequent decades.

The decline of democracy worldwide is driven by complex forces. Globalization and economic change have left many behind, and a huge cultural divide has emerged between highly educated professionals living in cities and residents of smaller towns with more traditional values. The rise of the internet has weakened elite control over information; we have always disagreed over values, but we now live in separate factual universes. And the desire to belong and have one’s dignity affirmed are often more powerful forces than economic self-interest.

The world thus looks very different from the way it did roughly 30 years ago, when the former Soviet Union collapsed. There were two key factors I underestimated back then — first, the difficulty of creating not just democracy, but also a modern, impartial, uncorrupt state; and second, the possibility of political decay in advanced democracies.

The American model has been decaying for some time. Since the mid-1990s, the country’s politics have become increasingly polarized and subject to continuing gridlock, which has prevented it from performing basic government functions like passing budgets. There were clear problems with American institutions — the influence of money in politics, the effects of a voting system increasingly unaligned with democratic choice — yet the country seemed to be unable to reform itself. Earlier periods of crisis like the Civil War and the Great Depression produced farsighted, institution-building leaders; not so in the first decades of the 21st century, which saw American policymakers presiding over two catastrophes — the Iraq war and the subprime financial crisis — and then witnessed the emergence of a shortsighted demagogue egging on an angry populist movement.

Up until Jan. 6, one might have seen these developments through the lens of ordinary American politics, with its disagreements on issues like trade, immigration and abortion. But the uprising marked the moment when a significant minority of Americans showed themselves willing to turn against American democracy itself and to use violence to achieve their ends. What has made Jan. 6 a particularly alarming stain (and strain) on U.S. democracy is the fact that the Republican Party, far from repudiating those who initiated and participated in the uprising, has sought to normalize it and purge from its own ranks those who were willing to tell the truth about the 2020 election as it looks ahead to 2024, when Mr. Trump might seek a restoration.

The impact of this event is still playing out on the global stage. Over the years, authoritarian leaders like Vladimir Putin of Russia and Aleksandr Lukashenko of Belarus have sought to manipulate election results and deny popular will. Conversely, losing candidates in elections in new democracies have often charged voter fraud in the face of largely free and fair elections. This happened last year in Peru, when Keiko Fujimori contested her loss to Pedro Castillo in the second round of the country’s presidential election. Brazil’s president, Jair Bolsonaro, has been laying the grounds for contesting this year’s presidential election by attacking the functioning of Brazil’s voting system, just as Mr. Trump spent the lead-up to the 2020 election undermining confidence in mail-in ballots.

Before Jan. 6, these kinds of antics would have been seen as the behavior of young and incompletely consolidated democracies, and the United States would have wagged its finger in condemnation. But it has now happened in the United States itself. America’s credibility in upholding a model of good democratic practice has been shredded.

This precedent is bad enough, but there are potentially even more dangerous consequences of Jan. 6. The global rollback of democracy has been led by two rising authoritarian countries, Russia and China. Both powers have irredentist claims on other people’s territory. President Putin has stated openly that he does not believe Ukraine to be a legitimately independent country but rather part of a much larger Russia. He has massed troops on Ukraine’s borders and has been testing Western responses to potential aggression. President Xi of China has asserted that Taiwan must eventually return to China, and Chinese leaders have not excluded the use of military force, if necessary.

A key factor in any future military aggression by either country will be the potential role of the United States, which has not extended clear security guarantees to either Ukraine or Taiwan but has been supportive militarily and ideologically aligned with those countries’ efforts to become real democracies.

If momentum had built in the Republican Party to renounce the events of Jan. 6 the way it ultimately abandoned Richard Nixon in 1974, we might have hoped that the country might move on from the Trump era. But this has not happened, and foreign adversaries like Russia and China are watching this situation with unconstrained glee. If issues like vaccinations and mask-wearing have become politicized and divisive, consider how a future decision to extend military support — or to deny such support — to either Ukraine or Taiwan would be greeted. Mr. Trump undermined the bipartisan consensus that existed since the late 1940s over America’s strong support for a liberal international role, and President Biden has not yet been able to re-establish it.

The single greatest weakness of the United States today lies in its internal divisions. Conservative pundits have traveled to illiberal Hungary to seek an alternative model, and a dismaying number of Republicans see the Democrats as a greater threat than Russia.

0 notes

Text

sittin on your lap singing you my songs

#coquette#coquette aesthetic#nymphcore#dolly aesthetic#amerian lolita#vintage americana#vintage coquette#lolita is not a love story

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

Hi hi! Thought I'd show you the Girls I own, my Oma made the clothes they are wearin. Wanted to go with a 50's theme. I think they look so cute 🥺 hope you like it!

submitted by @meadowlarker

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

not gonna actually rb but this is so funny to me bc it literally happens the other way around too like op is right but I'm with them on this being insufferable but we must also consider that maybe british and american people are both insufferable

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Word Vomit Post- Life in the USA and Diasporic Feelings

Coming back from summer holiday in Mexico, to go back to work sucks.

The life style is just so different. I hadn't visited my maternal extended family in 8 years and it has been 12 years since I've seen 3/4ths of my paternal extended family. I have 34 cousins on my paternal side and 47 cousins on my maternal side and I'm on the younger side of both sides. My mom is the 9th child of 12 (who survived infancy) and my dad is 6th child of 10 (who survived infancy). Feeling that sense of familiar belonging and knowing where my family is from is such a fulfilling feeling I never appreciated as a kid. I kinda made it my goal to learn as much as I could about my family before my last grandparent passes. He turned 90 and I felt such immense guilt for not seeing any of my grandparents before they passed.

I told myself I was never going to go back to Mexico after a bad experience/ traumatically public anxiety attack in 2015.

I didn't think I would miss being in Mexico.

The life style there is so much more, in lack of better words, Alive. Towns are colorful, odd shapes, people own/build their homes and expand them, to fit with their surrounding nature. No matter how much people lack in the small rural mountain towns, there is a community and belonging everywhere. In the street corners every evening neighbors sit out and greet each other. Go on walks in the paths, farm, take care of their land, harvest their crops, listen to the rain fall, feel the lightning electrify the air and jump when the thunder cracks the sound barrier. Though my family is from a rural mountain area, modern living did not skip them, and yet I still feel like their life style was not taken over by technology (probably cuz the rural mountain villages have so many power outages in the rainy season).

The only other time felt like I belonged when I was in my childhood home in California's Bay Area, before they gentrified my area and kicked out all the low income families, so that all the tech companies could control everyone's lives. Even living now in the Midwest, I never see anyone walking on the street, life revolves around working and mowing your lawn so that your neighbors don't judge you. I don't see kids riding their bikes or outside, everything is so far apart from each other (2 hours in each direction to get to a city where I can even find a Barn's and Noble, a book store or even to buy Boba milk tea). I have never meet so many people who go to the Walmart parking lot to kill time.

Maybe I'm just older now and don't understand the mid-west lifestyle. Maybe I'm missing the belonging I felt from my paternal side of the family in California. Maybe its my anxiety that makes me feel like I don't belong with my maternal family (tho I've tried to connect, and every time I do I always feel that feeling of failing to connect). Maybe its all just my anxiety and can't be content in finding the little things where I am.

I have never felt that feeling of failing to connect with my paternal and maternal family in Mexico... They all know I'm odd and they have never made me feel judged or like I don't belong.

Though I may not fit in in Mexico, I still feel like I belong there.

#Latin Amerian Diaspora#First Generation American#belonging#mexican american#doodle#katydoodles#Idk i just needed to vent a bit#idk how to tag#art#self portrait

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Decided to start beading again.

I started this on December 31st 2023 and Finished January 11 2024. I spent about an hour or two per day when possible. I plan to eventually put a backing on it and make a lanyard.

I've decided to do non-traditional things so I'm not giving away cultural designs.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

GOD me trying to triligually scam my way into free drinks in tokyo this is the real reason u should study a foreign language. for evil and stupid reasons

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

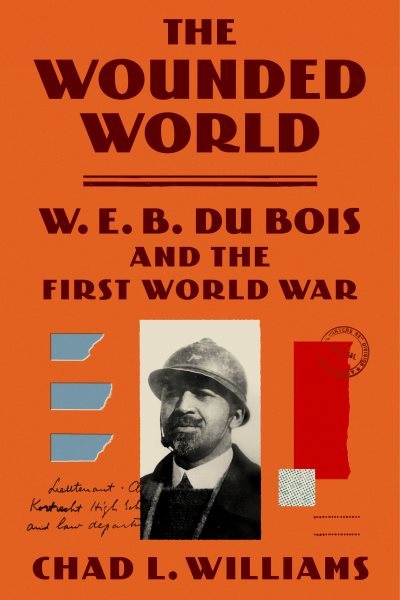

“I read The Wounded World: W. E. B. Du Bois and the First World War for pleasure—the pleasure of rigorous scholarship and narrative nuance, of the magisterial W. E. B. Du Bois in flesh and blood. In this extraordinary book, Chad Williams exploits the voluminous archive Du Bois collected in his ultimately failed quest to ease the tension between being Black and being American, a quest Williams presents in poignant clarity.”

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

#mercury#Marauder#mercury marauder#classic#history#historic#classic car#ford#ford history#mercury history#amerian#american car

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

i think??? tumblr just ate one of my asks???

so uuuhhh sorry to the anon that asked how the mercs would celebrate Archie's birthday sgyef

i'm gonna asnwer it here though

My idea was that they would celebrate like any other birthday!

They would definetly have to explain to him what the concept of a birthday is though, i think he'd be pretty confused at first

#wolfart asks#wolfart talks#human!archimedes#tf2 oc#they would also all get him presents#thogu hsome of them are definetly not fit for someone who is 1 years old...#like Sniper giving him a swiss knife#or Engie giving him a set of screwdrivers#or Pyro giving him one of those gas lighters...#or Medic giving him a book about human bilogy (with some medical equipment to go long with it)#honestly probably hte only normal gifts would be from Scout Heavy Demo and Spy (?)#Scout would get him a pair of headphones or a sketchbook and some crayons#Heavy would give him eider a sweater or a kids book to help him learn how to read#and spy would probably give him some expensive clothes or Cologne#which is not that bad? i guess#Demo would give him some bigass lego set (then proceed to sit and build it with him for like 6 hours). he gets it#Soldier would get him an amerian flag. or a second cake (in the shape of an american flag)#or a rocket launcher (so they can practice rocket jumps together (Archie is scared of rocket jumping. but he appreciates the gesture))

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

One Single Day. That’s All It Took for the World to Look Away From Us

This article is part of a collection on the events of Jan. 6, one year later. Read more in a note from Times Opinion’s politics editor Ezekiel Kweku in our Opinion Today newsletter.

The Jan. 6 attack on Congress by a mob inspired by former President Donald Trump marked an ominous precedent for U.S. politics. Not since the Civil War had the country failed to effect a peaceful transfer of power, and no previous candidate purposefully contested an election’s results in the face of broad evidence that it was free and fair.

The event continues to reverberate in American politics — but its impact is not just domestic. It has also had a large impact internationally and signals a significant decline in American global power and influence.

Jan. 6 needs to be seen against the backdrop of the broader global crisis of liberal democracy. According to Freedom House’s 2021 Freedom in the World report, democracy has been in decline for 15 straight years, with some of the largest setbacks coming in the world’s two largest democracies, the United States and India. Since that report was issued, coups took place in Myanmar, Tunisia and Sudan, countries that had previously taken promising steps toward democracy.

The world had experienced a huge expansion in the number of democracies, from around 35 in the early 1970s to well over 110 by the time of the 2008 financial crisis. The United States was critical to what was labeled the “Third Wave” of democratization. America provided security to democratic allies in Europe and East Asia, and presided over an increasingly integrated global economy that quadrupled its output in that same period.

But global democracy was underpinned by the success and durability of democracy in the United States itself — what the political scientist Joseph Nye labels its “soft power.” People around the world looked up to America’s example as one they sought to emulate, from the students in Tiananmen Square in 1989 to the protesters leading the “color revolutions” in Europe and the Middle East in subsequent decades.

The decline of democracy worldwide is driven by complex forces. Globalization and economic change have left many behind, and a huge cultural divide has emerged between highly educated professionals living in cities and residents of smaller towns with more traditional values. The rise of the internet has weakened elite control over information; we have always disagreed over values, but we now live in separate factual universes. And the desire to belong and have one’s dignity affirmed are often more powerful forces than economic self-interest.

The world thus looks very different from the way it did roughly 30 years ago, when the former Soviet Union collapsed. There were two key factors I underestimated back then — first, the difficulty of creating not just democracy, but also a modern, impartial, uncorrupt state; and second, the possibility of political decay in advanced democracies.

The American model has been decaying for some time. Since the mid-1990s, the country’s politics have become increasingly polarized and subject to continuing gridlock, which has prevented it from performing basic government functions like passing budgets. There were clear problems with American institutions — the influence of money in politics, the effects of a voting system increasingly unaligned with democratic choice — yet the country seemed to be unable to reform itself. Earlier periods of crisis like the Civil War and the Great Depression produced farsighted, institution-building leaders; not so in the first decades of the 21st century, which saw American policymakers presiding over two catastrophes — the Iraq war and the subprime financial crisis — and then witnessed the emergence of a shortsighted demagogue egging on an angry populist movement.

Up until Jan. 6, one might have seen these developments through the lens of ordinary American politics, with its disagreements on issues like trade, immigration and abortion. But the uprising marked the moment when a significant minority of Americans showed themselves willing to turn against American democracy itself and to use violence to achieve their ends. What has made Jan. 6 a particularly alarming stain (and strain) on U.S. democracy is the fact that the Republican Party, far from repudiating those who initiated and participated in the uprising, has sought to normalize it and purge from its own ranks those who were willing to tell the truth about the 2020 election as it looks ahead to 2024, when Mr. Trump might seek a restoration.

The impact of this event is still playing out on the global stage. Over the years, authoritarian leaders like Vladimir Putin of Russia and Aleksandr Lukashenko of Belarus have sought to manipulate election results and deny popular will. Conversely, losing candidates in elections in new democracies have often charged voter fraud in the face of largely free and fair elections. This happened last year in Peru, when Keiko Fujimori contested her loss to Pedro Castillo in the second round of the country’s presidential election. Brazil’s president, Jair Bolsonaro, has been laying the grounds for contesting this year’s presidential election by attacking the functioning of Brazil’s voting system, just as Mr. Trump spent the lead-up to the 2020 election undermining confidence in mail-in ballots.

Before Jan. 6, these kinds of antics would have been seen as the behavior of young and incompletely consolidated democracies, and the United States would have wagged its finger in condemnation. But it has now happened in the United States itself. America’s credibility in upholding a model of good democratic practice has been shredded.

This precedent is bad enough, but there are potentially even more dangerous consequences of Jan. 6. The global rollback of democracy has been led by two rising authoritarian countries, Russia and China. Both powers have irredentist claims on other people’s territory. President Putin has stated openly that he does not believe Ukraine to be a legitimately independent country but rather part of a much larger Russia. He has massed troops on Ukraine’s borders and has been testing Western responses to potential aggression. President Xi of China has asserted that Taiwan must eventually return to China, and Chinese leaders have not excluded the use of military force, if necessary.

A key factor in any future military aggression by either country will be the potential role of the United States, which has not extended clear security guarantees to either Ukraine or Taiwan but has been supportive militarily and ideologically aligned with those countries’ efforts to become real democracies.

If momentum had built in the Republican Party to renounce the events of Jan. 6 the way it ultimately abandoned Richard Nixon in 1974, we might have hoped that the country might move on from the Trump era. But this has not happened, and foreign adversaries like Russia and China are watching this situation with unconstrained glee. If issues like vaccinations and mask-wearing have become politicized and divisive, consider how a future decision to extend military support — or to deny such support — to either Ukraine or Taiwan would be greeted. Mr. Trump undermined the bipartisan consensus that existed since the late 1940s over America’s strong support for a liberal international role, and President Biden has not yet been able to re-establish it.

The single greatest weakness of the United States today lies in its internal divisions. Conservative pundits have traveled to illiberal Hungary to seek an alternative model, and a dismaying number of Republicans see the Democrats as a greater threat than Russia.

0 notes

Text

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

wow haha kinda weird that caleb's palisman was called flapjack haha surely the word can't be that old

hang on....

HANG ON....

oh my scars and barters

#the owl house#toh spoilers#they really did their research huh#love how amerians are all like ''aww he's a pancake''#no. he's been a nature valley granola bar the whole time#maybe that's why hunter's so prone to falling apart......

90 notes

·

View notes