#an atlas of insect morphology

Text

My gift to you: An Atlas of Insect Morphology free pdf

5K notes

·

View notes

Photo

Royal Ontario Museum - Insect Exhibits 1

Well this is certainly different and there are a lot more insects than usual! Must be a special occasion, and it absolutely is! I’m dedicating this post to Ally, one of my dearest friends and a major inspiration for this blog. We’ve known each other for around 7 years now, having met in U of T’s 3rd year Insect Biology course. We’ve been on many a bug hunt together (and hopefully more in the future)! She loves insects even more than I do, so much so that she continues to study entomology at the University of Guelph, alongside the role the many insects play in the environment! I’m so proud of her! Hop onto Google Scholar to discover her work on the insect world or check out her blog to see her insight: Ecology for Life (@Ecology_forlife). In honoring her today, today’s showcase will briefly cover the ROM’s amazing insect collections* and how museums are useful for insect research and inspiring interest. Thank you for everything, dearest Bug Princess! May fortune continue to smile upon you!

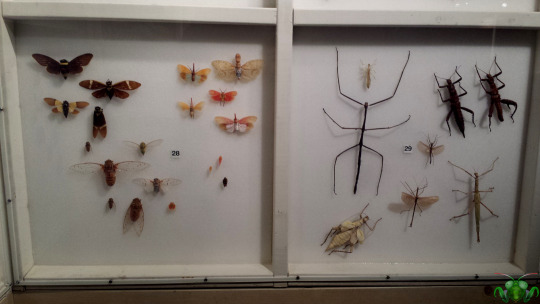

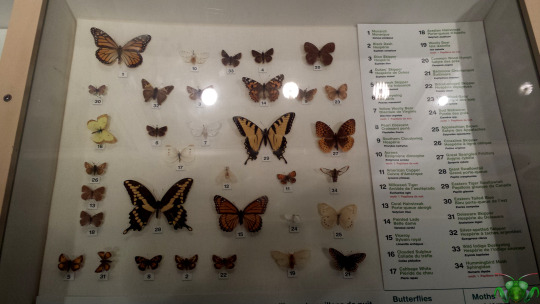

While it may not specialize in insects, the ROM boasts some amazing collections of insects. There are quite a few tropical and exotic species to see including such notable finds like the Atlas Moth (Attacus atlas), the Peanut-Head Lanternfly (Fulgora laternaria), the many shimmering, iridescent Butterflies including the Blue Morpho (Morpho spp.) and Green Birdwing (Ornithoptera priamus), giant Stick Insects, Cicadas, tropical Grasshoppers and many Beetles like the ornate and horned Scarabs, the giant Harlequin Beetles (Acrocinus longimanus) or even oddities like the Violin Beetle (Mormolyce phyllodes). While these are fantastical, there are also bug boxes that contain insect species that are more familiar to us, allowing patrons to compare the insects of our region with those on the other side of the world. They might even recognize a few from their neighborhood. That organized Butterfly box has certainly been a useful reference for the identification of a few species. Honestly, picture don’t do it justice; if you’re an insect enthusiast, see these collections in person and notice that there’s also 1 spider and 1 centipede mounted as well.

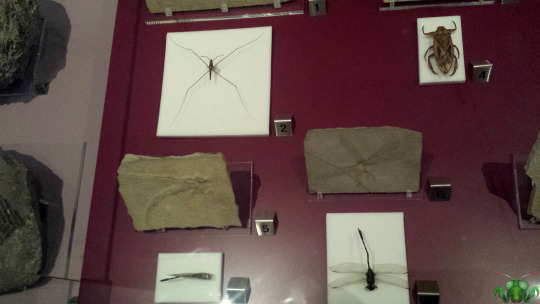

Alongside the showcase of modern day insects within the ecology and biodiversity sections of the ROM, they are showcased in one other area too. The fossil section of the ROM carries fossilized insects (or fossil preservations) both in stone and within resin (look for the those in the ancient mammal area). These fossils are placed alongside their modern counterparts to highlight the changes time has brought to the world of arthropods. It seems many of them have gotten a little bit smaller. While the morphology appears consistent, many small changes have taken place over the hundreds of millions of years insects have crawled and flown over the Earth. The age of the fossils can also help us better understand the evolutionary timeline of these little creatures. All this while behind the scenes there are dedicated personnel working hard to push science and our understanding of the natural world forward! And of course, if all this insight into the scope and grandeur of the insect world isn’t enough, there are live insects to observe and enjoy at the ROM too including a Honeybee nest, Darkling Beetles, Walking Sticks and Hissing Roaches. And this is just one museum; many other institutions bring their own amazing contributions to the collective knowledge of insects.

*Note: Since these insect collections belong to the ROM, I’ve marked them with the Mantis icon. The poster is mine though. When things are safe/back to normal, I’ll return to the ROM for a follow-up (and I did return with new insect showcases: 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |).

ROM Pictures were taken on April 15, 2019 with Samsung Galaxy S4 and the poster picture was taken November 24, 2021 with a Google Pixel 4. Click on this link to view ROM - Insect Exhibits 2.

#jonny’s insect catalogue#insect#Royal Ontario Museum#insect box#insect showcase#ROM insect#bug box#insect poster#lepidoptera#orthoptera#hemiptera#phasmatodea#coleoptera#odonata#mantodea#butterfly#moth#beetle#dragonfly#cicada#stick insect#true bug#pond skater#giant water bug#grasshopper#cricket#lanternfly#lantern fly#scolops bug#peanut bug

56 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sagittarius serpentarius

By Ikiwaner, GFDL 1.2

Etymology: Archer

First Described By: Hermann, 1783

Classification: Dinosauromorpha, Dinosauriformes, Dracohors, Dinosauria, Saurischia, Eusaurischia, Theropoda, Neotheropoda, Averostra, Tetanurae, Orionides, Avetheropoda, Coelurosauria, Tyrannoraptora, Maniraptoromorpha, Maniraptoriformes, Maniraptora, Pennaraptora, Paraves, Eumaniraptora, Averaptora, Avialae, Euavialae, Avebrevicauda, Pygostaylia, Ornithothoraces, Euornithes, Ornithuromorpha, Ornithurae, Neornithes, Neognathae, Neoaves, Inopinaves, Telluraves, Afroaves, Accipitrimorphae, Accipitriformes, Sagittariidae

Status: Extant, Vulnerable

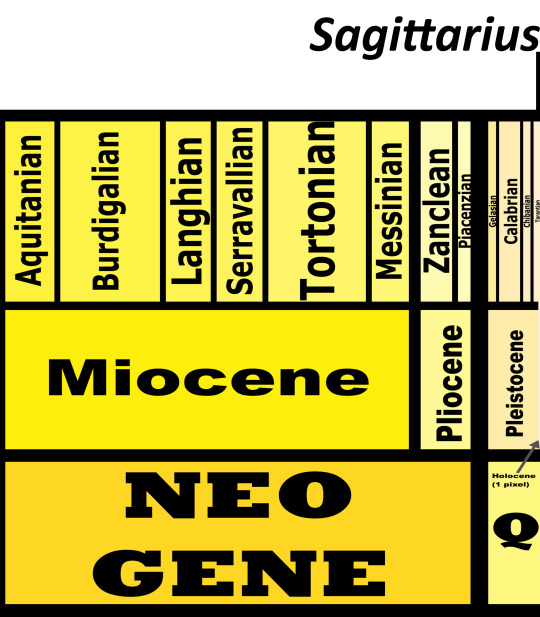

Time and Place: Within the last 10,000 years, in the Holocene of the Quaternary

The Secretarybird is known from a variety of arid (re: non-dense tropical rainforests) across sub-Saharan Africa

Physical Description: Secretarybirds are among the most visually distinctive of living dinosaurs, and one of the species usually pointed to by people attempting to prove the dinosaur nature of birds via visual evidence. These are large raptors, with extremely long and thin legs like those of storks. They have sharp talons on their feet, and they are truly living the “Velociraptor is my great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great-great auntie and I’m here to kick your ass” life.

They still have the ability to fly, with large wings and elongated bodies - including long, stiffened tail feathers just to add to the whole “wait if I squint maybe it has a bony tail like a Velociraptor” appearance it has going on. It has a medium-length neck, with a small head and a distinctive crest of thin feathers off the back of its head. It also has a downward-curved, sharp beak.

By Lip Kee Yap, CC BY-SA 2.0

In terms of color, the Secretarybirds have orange patches over their eyes, and mainly white heads besides; the ends of their crest feathers are black. Their leg feathers are black too, as are some of their rump feathers, the tips of their wings, their backs, and the ends of their tails. The males and females look roughly the same, with the females somewhat smaller than the males. In general, they range between 125 and 150 centimeters in length. Juveniles are very similar to the adults, but with shorter crests and tails. In short, these are raptors that aren’t actually mistaken for other raptors - but might be mistaken for cranes!

The Secretarybird is interesting on the inside as well - it has a very short digestive tract, and a foregut highly specialized for digesting large quantities of meat very quickly. They don’t have a muscular gizzard like other birds, and they don’t have any fermentation agents since they don’t eat plants at all!

By Biran Ralphs, CC BY 2.0

Diet: Though it can fly, the Secretarybird does the entirety of its hunting on the ground, stalking through the grass to catch a variety of meat prey including mammals as big as mongooses, lizards, snakes, tortoises, other birds, eggs, crabs, and insects. They do kill even bigger mammals like young gazelles and cheetah cubs. In short, they’re making their ancestors proud.

Behavior: Secretarybirds have a lot of very distinctive behaviors that make them iconic, bird-wise, among the masses. Most especially, they engage in very fast kicking with their long legs in order to grab prey - evoking images of dinosaurs gone by. These kicks are fast, powerful, and terrifying - and then on top of that insanity, they swallow their food whole with their large, gaping beaks! To get their food out of hiding, they even stomp incessantly on the ground in order to flush it out. They usually only tear up their food with their toes while holding it down, not bothering to chop it up with their beaks. Sometimes they’ll even jump down onto food, using a little bit of raptor-prey-restraint or lift with their wings to get the jump on their prey. These birds usually hunt alone, or with their mate nearby.

youtube

These birds do not migrate much, but they can be nomadic in response to rainfall and fires. The juveniles especially travel far in search of areas unoccupied by mated pairs. They make high pitched, “ko-ko-ko-ko-ko-ka” calls to one another, in addition to more “kowaaaaaaa kowaaaaaaaa” and “kurrk-urr-kurrk-urr” calls back and forth. They aren’t actually that good at running, despite their long legs - they instead are really only good for the stomp-strike they use for hunting.

By Donald Macauley, CC BY-SA 2.0

These birds form monogamous pairs, that stay together for most of their lives. They have an elaborate courtship display for one another that involves soaring high and flying in an undulated fashion around each other, and croaking at each other. Sometimes they also will court each other on the ground, chasing each other with their wings up like how they chase prey. They will nest any time of the year, usually corresponding to abundance of food. They especially raise chicks in the rainy system. Their nests are made fairly high up in Acacia trees, made out of sticks with dense grass and wool lining, usually made in the shape of a saucer. THey lay between 1 and 3 eggs in a nest, which are incubated by both parents for about a month and a half. The chicks are pale grey and fluffy with short, straight bills; they moult twice before reaching a juvenile plumage at six weeks. They are dependent on their parents for over three months; their parents will eat insects and then regurgitate them back into the young’s mouths. The parents teach their young how to hunt extensively, in order for them to be independent by the end of their rearing period.

By Kore, CC BY-SA 3.0

Ecosystem: Secretarybirds live in steppes and savanna, especially enjoying short grasses with scattered trees for roosting and nesting. They rarely go anywhere with more trees. They can be found at a variety of elevations. Here they live with a wide variety of animals, especially venomous snakes, which they are famous for eating. However, their own young are fed upon by crows, ravens, hornbills, kites, and owls.

Other: Secretarybirds are considered vulnerable to extinction, mainly due to extensive habitat loss and rising CO2 levels. These birds are still widespread across Africa and are becoming adapted to more arid, desert-like habitats, but despite this common nature of the species they are still listed as vulnerable due to a recent rapid decline across the entirety of their range. They are a very revered bird in Africa, used as the emblem of Sudan and a motif on postage stamps - though they are also called the Devil’s Horse!

By Yoky, CC BY-SA 3.0

As to the peculiar name, some think it is because the crest feathers look like quill feathers for a pen, leading to the association with a secretary - but this hypothesis has fallen out of favor. Some may think it is a mishearing of the French “Saqr-et-tair”, aka, hunter bird. Either way, the quills also look like a quiver of arrows - and it is a skilled hunter - leading to its genus name being Sagittarius, aka, Archer!

~ By Meig Dickson

Sources under the Cut

Allan, D.G.; Harrison, J.A.; Navarro, R.A.; van Wilgen, B.W.; Thompson, M.W. (1997). "The Impact of Commercial Afforestation on Bird Population in Mpumalanga Province, South Africa – Insights from Bird-Atlas Data". Biological Conservation. 79 (2–3): 173–185.

Jobling, J. A. 2010. The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. Christopher Helm Publishing, A&C Black Publishers Ltd, London.

Kemp, A.C. (2019). Secretarybird (Sagittariidae). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Kemp, A.C., Kirwan, G.M., Christie, D.A. & Marks, J.S. (2019). Secretarybird (Sagittarius serpentarius). In: del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A., Sargatal, J., Christie, D.A. & de Juana, E. (eds.). Handbook of the Birds of the World Alive. Lynx Edicions, Barcelona.

Maloiy, G. M. O.; Alexander, R. M. C. N.; Njau, R.; Jayes, A. S. (1979). "Allometry of the legs of running birds". Journal of Zoology. 187 (2): 161–167.

Mayr, G.; Clarke, J. (2003). "The deep divergences of neornithine birds: a phylogenetic analysis of morphological characters". Cladistics. 19 (6): 527–553.

Scharning, Kjell. "Secretary Bird Sagittarius serpentarius". Theme Birds on Stamps. Archived from the original on 18 January 2018.

Sherman, Patrick (2007). "Sagittarius serpentarius : secretary bird". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology.

Simmons, R.E. (2015). "Secretarybird – Sagittarius serpentarius". In R.E. Simmons; C.J. Brown; J. Kemper (eds.). Bird to watch in Namibia – red, rare and endangered species. Namibian Ministry of Environment and Tourism, and the Namibia Nature Foundation.

Todd, William T. (1988). "Hand-Rearing the Secretary Bird Sagitarius Serpentarius at Oklahoma City Zoo". International Zoo Yearbook. 27 (1): 258–263.

#Sagittarius serpentarius#Secretarybird#Sagittarius#bird#Dinosaur#Birblr#Factfile#Bird of Prey#Raptor#Secretary Bird#Dinosaurs#Birds#Quaternary#Africa#Theropod Thursday#Carnivore#Accipitrimorph#prehistoric life#biology#a dinosaur a day#a-dinosaur-a-day#dinosaur of the day#dinosaur-of-the-day#science#nature

394 notes

·

View notes