#an autumn afternoon

Text

Mariko Okada in Floating Clouds (1955), Flowing (1956), Late Autumn (1960), and An Autumn Afternoon (1962).

#Mariko Okada#岡田茉莉子#Floating Clouds#Flowing#Late Autumn#An Autumn Afternoon#Mikio Naruse#成瀬巳喜男#浮雲#流れる#Nagareru#秋日和#Yasujirō Ozu#Yasujiro Ozu#小津安二郎#秋刀魚の味

317 notes

·

View notes

Text

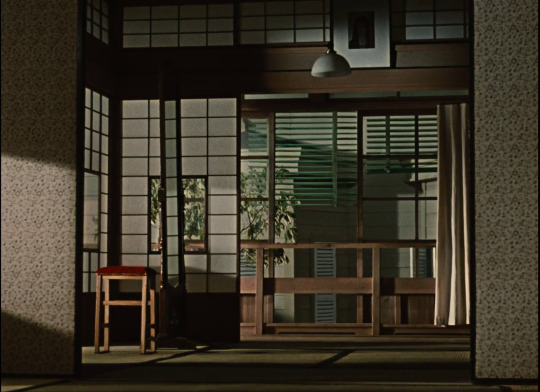

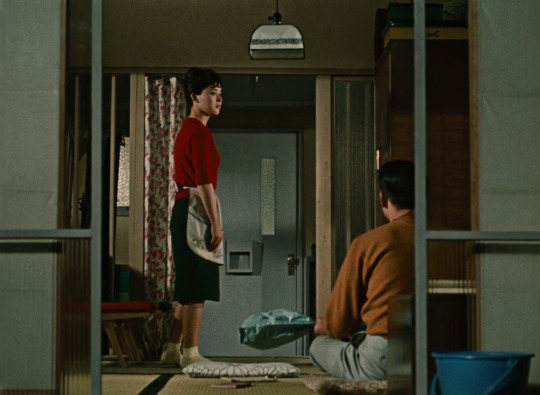

An Autumn Afternoon (1962) | dir. Yasujirō Ozu

#an autumn afternoon#yasujirō ozu#chishū ryū#shima iwashita#keiji sada#mariko okada#films#movies#cinematography#screencaps#yasujiro ozu

151 notes

·

View notes

Text

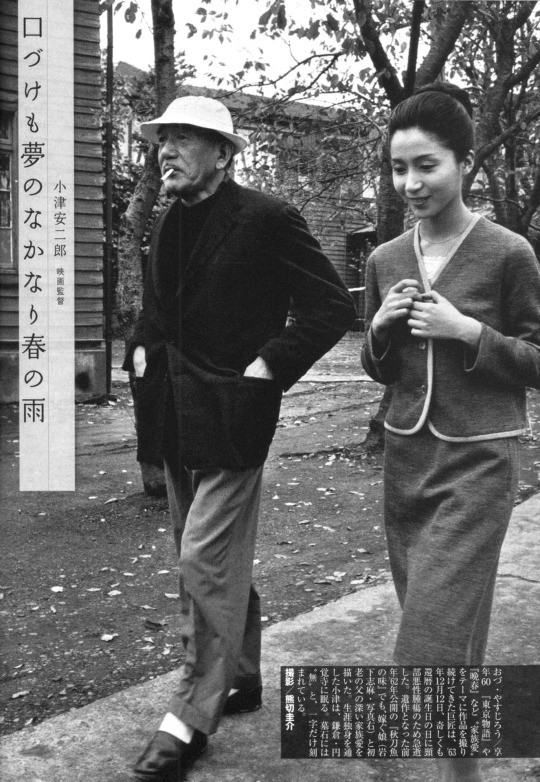

Yasujiro Ozu et Shima Iwashita

1962

172 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Autumn Afternoon, Yasujiro Ozu, 1962

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yasujiro Ozu and Shima Iwashita in « An Autumn Afternoon » (1962)

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

#autumn#fall#the ber months#september#October#november#an autumn afternoon#autumn quotes#fall quotes#seasons#i love fall#cozy#snuggle#pumpkins#chill in the air#pumpkin spice#get cozy#boots#sweaters#candles#blankets#trick or treat

145 notes

·

View notes

Text

IT HURTS TO BE ALONE

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

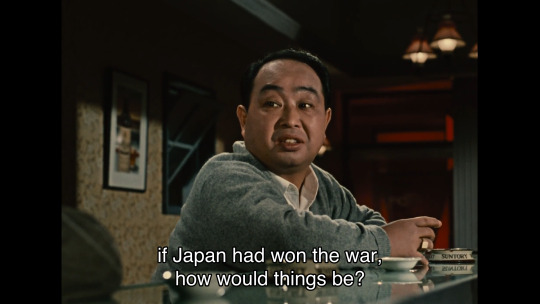

An Autumn Afternoon (1962) x Jeanne Dielman (1975)

So yesterday I finally took the time to watch Yasujirō Ozu's An Autumn Afternoon and I couldn't help but to draw a bunch of parallels between this film and Chantal Akerman's masterpiece Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du commerce, 1080 Bruxelles.

The first aspect of similarity is the photography, with the camera always still working its way through delicate compositions.

But what stroke me as more shocking is how one film seems to complement the other. An Autumn Afternoon is a film about the weight of patriarchy on everybody that has to live under its shadow, specially women, confined to doing the laborious work of the house, which in the film is always invisible, but in a way that makes you understand the importance and intricacy of the work that those women perform. It's mentioned, as if leaking through the seams while we're only presented in detail with the scenes of the encounters between a group of man.

As much as in the narrative (that for the first half of the film takes the perspective of the man) the woman are put as side characters, visually they get center priority, which implies the importance and strength of those characters, even though they are treated as assets by their counterparts.

Yasujirō Ozu creates a powerful film that is not so concerned about a narrative, but exposes contexts in which we can observe the toll gender roles play in society and how we’re confined to keep perpetuating these ideals for lack of perpective of their harm.

In a scene at a bar one character asks "if Japan won the war, how would things be?" and the answer is: everything would be the same for the woman who live under the patriarchal system you're all subjected to, and to an extent, to the man who have to deal with the frustrations of not being able to achieve certain expectations set for their roles.

Meanwhile, in Jeane Dielman you're confronted only with the work performed by woman, the ritualistic never ending routine of the housewife, its as if one film shows what the other one consciously hides.

I want to discuss this connection and this subject more in depth on my newsletter, but I just needed to get the idea out there so I don't forget.

11 notes

·

View notes

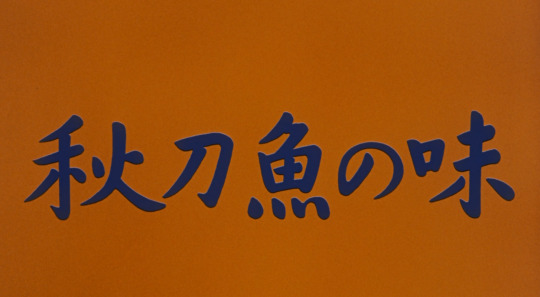

Photo

1962 秋刀魚の味

An Autumn Afternoon

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

Chishū Ryū in the final shots of:

LATE SPRING (1949) dir. Yasujirō Ozu

AN AUTUMN AFTERNOON (1962) dir. Yasujirō Ozu

#late spring#an autumn afternoon#yasujirō ozu#Chishū Ryū#these ending shots…….. yeah.#ozu said I’m gonna remake the same film with the same characters and actors and it’s going to be just as good but also completely distinct#honestly comparing the two films just makes me feel so many things and I don’t understand most of those feelings#ozu is an absolute master and he destroys me always#yasujiro ozu#chishu ryu#japanese movie#screencaps#parallellis#ozu parallels#queue

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

#marthur#mary linton#mary gillis#rdr2#red dead redemption 2#arthur morgan#red dead redemption#rdr#an autumn afternoon#autumn leaves#autumn date#sorry this is low quality

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

An Autumn Afternoon (1962) | dir. Yasujirō Ozu

#an autumn afternoon#yasujirō ozu#chishū ryū#shima iwashita#keiji sada#mariko okada#films#movies#cinematography#screencaps#yasujiro ozu

184 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Chishu Ryu in An Autumn Afternoon (Yasujiro Ozu, 1963)

Cast: Chishu Ryu, Shima Iwashita, Keiji Sada, Mariko Okada, Teruo Yushida, Noriko Maki, Shin'ichiro Mikami, Nobuo Nakamura, Kuniko Miyake, Eijiro Tono, Haruko Sugimura, Kyoko Kishida, Daisuke Kato. Screenplay: Kogo Noda, Yasujiro Ozu. Cinematography: Yuharu Atsuta. Production design: Minoru Kanekatsu

If a foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds, then what is a wise consistency? Because Yasujiro Ozu was nothing if not consistent, especially in the films of his greatest period: From Late Spring (1949) through An Autumn Afternoon, his final film, we get the same milieu -- middle class Japanese family life -- with the same problems -- aging parents, marriageable daughters, unruly children -- and the same style -- low-angle shots, stationary camera, boxlike interiors, exterior shots of buildings and landscape used to punctuate the narrative. Ozu's style would be called "mannered" except that the word suggests an obtrusive inflection of style for style's sake, whereas Ozu's style is unobtrusive, dedicated to the service of storytelling. There are, I suppose, some who are turned off by such consistency, who don't "get" Ozu. All I can say is that it's their loss, because it's a wise consistency, dedicated to trying to understand the way people work, why, for example, they conceal and obfuscate and manipulate to get what they really want. And why, sometimes, they don't even know what they really want. An Autumn Afternoon could almost be mistaken for a remake of Late Spring because of its central problem: a young woman at risk of sacrificing herself for an aging, widowed father. It stars the same actor, Chishu Ryu, as the father, Shuhei, and it ends in a strikingly similar way: The daughter, Michiko (Shima Iwashita), gets married, but we never see the bridegroom, just as we never see the man Noriko marries in Late Spring. But where Late Spring centered itself on a kind of moral dilemma, the white lie the father tells to resolve the problem, An Autumn Afternoon illuminates the relationship of father and daughter through the experiences of secondary characters. If Michiko marries, will her marriage be like that of her brother and sister-in-law, strained by constant arguments about money? If Shuhei doesn't encourage her to marry, will she end up like the daughter of his old teacher, embittered because she gave up the prospect of marriage to serve him? There's yet another possibility for Shuhei: His close friend, a widower, remarried, but now his much younger wife has him on a tight leash, putting limits on him that Shuhei doesn't have, such as the ability to stop off in bars and to drink with his old war buddies. (Even Michiko tries to rein in her father where this is concerned, pointedly commenting when Shuhei comes home a little late and tipsy.) The screenplay by Ozu and his usual collaborator, Kogo Noda, deftly integrates all of these stories and more, but the shining center of the film is the performance of Ryu, constantly letting us see the conflict that is churning beneath Shuhei's calm demeanor. And it's entirely fitting that the final shot of Ozu's last film -- Shuhei, saying softly to himself, "Alone, eh?" -- features Ryu, the actor who appeared in so many of his films that he seemed to be Ozu's alter ego.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

I couldn’t find Ozu’s “An Autumn Afternoon” on YouTube in full so I watched this video instead:

youtube

Based on this summary it seems to be a remake of Late Spring, only much less intense and without Setsuko Hara’s smile.

Based on this video, I wonder why Ozu even made it. Maybe he thought that he was too quick to establish this plot as an intense tragedy in Late Spring and decided to give it a more level-headed and balanced treatment later in his career.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Traditions in transition: cinematic perspectives on the modernization of post-war societies (¼)

The following article is the first in a four-part series looking at how cinema depicts post-war societies’ transformations, and more precisely the transition from a traditional society to a modern one. In order to examine our topic from all angles, every installment of this series will be dedicated to a separate movie, each originating from a different country. Since context is essential to better understand what lies beneath images, and thus propose an in-depth analysis, I will always start by introducing the director and the significant historical events surrounding the films’ releases.

In this inaugural piece, we deal with Yasujirō Ozu’s An Autumn Afternoon (1962) portrayal of westernization and women’s emancipation amidst the Japan societal shifts of the 1960s. Through this work, I wish to highlight the multifaceted societal changes that come with post-war modernization, be it urban and rural spaces experiencing deep transformations due to industrialization, or the evolution of social norms and behaviors.

Part 1. An Autumn Afternoon (秋刀魚の味 The taste of Sanma, Yasujirō Ozu, 1962): westernization of Japanese everyday life and Women’s emancipation

youtube

An Autumn Afternoon's Original Trailer

Japan was propelled into the modern era because of the “Meiji Restoration”, a political event that took place in 1868 and brought about notable changes in the pre-modern feudal society. Commodore Matthew Perry’s visit in 1853 had a part to play in these transformations by leading the Japanese government to realize their “late-developing” status, thus causing the demise of the long-reigning Tokugawa shogunate and the disintegration of a status-ordered system. Accordingly, the “Meiji Restoration” saw the development of small-scale industries, an explosive growth of urban populations, the rise of commerce and the dissemination of education. Despite adopting Western models in areas like law, economy, politics, science and technology, Japan kept its customs and traditions alive. However, upon the completion of its industrial revolution in 1910, Japanese society went through a stagnating period. In fact, economic and social restructuring, which had become crucial, was still not fully achieved.

35 years later, the Axis defeat led to Japan’s occupation by the Allied Forces. Until the Peace Treaty was concluded in September 1951, The S.C.A.P (Supreme Commander for Allied Powers) imposed several reforms, including the adoption of a new constitution in May of 1947. The principle of popular sovereignty was established, and the patriarchy family system abolished. The focus was now on economic reconstruction.

Please CHECK the following article for further historical information

By the 1960s, Japan had emerged from the devastation of World War II and embarked on a path of economic growth, technological advancements and international integration. This era, known as the “economic miracle”, witnessed significant generational shifts. All of which deeply influenced Yasujirō Ozu’s filmography. Especially as the filmmaker was born in 1903 into a middle-class family and has lived through a good part of these dramatic changes.

Set in post-war Japan, An Autumn Afternoon stars Ozu’s regular Chishū Ryū as Shūhei Hirayama, a middle-aged widower and executive at a factory. Hirayama lives with his grown daughter, Michiko (Shima Iwashita), and younger son, Kazuo (Shinichirō Mikami). His elder son, Kōichi (Keiji Sada) has moved out to live with his wife, Akiko (Mariko Okada), leaving Shūhei to be looked after by Michiko. As was the custom in Japan, in the event of the mother’s death, the daughter looks after the family and the household until she eventually marries. At the same time, women are expected to take on domestic roles and marry at a young age, because “older never marry”. As the story unfolds, Shūhei Hirayama’s colleagues and friends begin to express their concern about Michiko’s unmarried status and urge him to find her a suitable husband. Feeling the weight of societal expectations and his own sense of duty, he resigns himself to arrange a marriage for his daughter and encourage her departure from their home. Although the emphasis on this theme may seem, at first, antiquated and patriarchal, women's desire for emancipation is very much present in the atmosphere. Michiko and Akiko, while accepting the traditional roles that society had accorded them, often express their disapproval of certain male behaviors, by refusing to serve them as expected or by questioning their decisions. Both are not afraid to make their voices heard.

Equinox Flower, Yasujirō Ozu, 1958

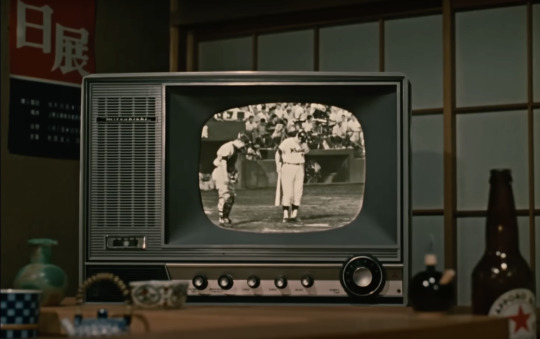

Notwithstanding the progress in the early 1960s, Japan remained dependent on Western technology imports for a long time, which were really expensive. This period also sees the transition towards television as a dominant medium of communication and entertainment. Due to this Western mass media exposure (movies, commercials, sport events, etc.), younger generations were greatly influenced by Hollywood and American popular culture. Equinox Flower, directed in 1958 already depicted urban dwellers, soda lovers.

An Autumn Afternoon, Yasujirō Ozu, 1962

In one of the most memorable scenes of An Autumn Afternoon, Shūhei Hirayama and his friends are seated on the floor, around a low table, as was the custom in traditional Japanese restaurants and households. The scene is filmed in Ozu’s regular static low-angle shots, commonly called “tatami” shots. On the opposite side of the restaurant, other clients are having dinner while watching a televised baseball match. Everyone sits around the same Western-style table, but there's no exchange. This juxtaposition beautifully encapsulates the fading traditions and Western growing influence in post-war Japanese society. The setting serves as a microcosm of the societal shifts portrayed throughout the film.

An Autumn Afternoon's opening sequence, Yasujirō Ozu, 1962

I can't conclude this first article without mentioning Ozu’s use of factory shots in the opening sequence. Also known as “pillow shots”, they are devoid of human presence and serve no narrative purpose other than marking time passing and transitions. In this case, they are a nod to the deep spatial transformations caused by industrialization. Factories and industrial areas are very much present in Ozu’s cinema, and are more often than not used as “pillow shots” or a backdrop, as in The Only Son (1936).

The Only Son, Yasujirō Ozu, 1936

An Autumn Afternoon is Ozu’s last movie before his death in December 1963. The original title of this film means “The taste of Sanma”, where Sanma is a mackerel pike. While never translated correctly, it carries a sense of nostalgia for a vanishing world, its customs and traditions. Like a Proust madeleine, “The taste of Sanma” dredges up a long-lost memory, reflecting on the complexities of post-war Japanese society.

Thank you for joining me on this journey. I genuinely appreciate your interest and support. Please stay tuned so you don't miss my upcoming article. Next time, We’ll be leaving for 1950s Norway through Kitchen Stories (2003). We’ll studying how social and environmental impacts of the Norwegian post-war industrial boom are depicted by movie director Bent Hamer.

Ruth Sarfati

0 notes