#anna tsing

Text

youtube

#mushrooms#fungi#book#books and reading#bookblr#livre#booktube#youtube#reading vlog#lifestyle#organizing#watercolor#reading for 24h#the poppy war#rf kuang#ghostcore#ghost music#an yu#the mushroom at the end of the world#anna tsing#annihilation#jeff vandermeer#this world is full of monsters#art#Youtube#goblincore#cottagecore

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

Without collaborations, we all die.

The Mushroom at the End of the World by Anna Tsing

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Anna Tsingiving!

Above: Anna Tsing by Little maquisart via Wikicommons. (check out her Instagram for more).

Below: Anna Tsing photographed by Fifi Zhou via Art Review

Because of the American Thanksgiving holiday I will queue up some images of Anna Tsing to keep you busy while I am away.

This Tumblr is less than than 50 people away from having 1000 follows. If you've liked it, perhaps you could promote it to put it over the mark.

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

In what tense

In what tense does one write an ethnographic account? This grammatical detail has considerable intellectual and political significance.... To many readers, using the past tense about an out-of-the- way place suggests not that people ‘have’ history but that they are history.”

— Anna Tsing, In the Realm of the Diamond Queen (1993)

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

I've been thinking a lot about mushrooms, and I think everybody else has too.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The concept of assemblage—an open-ended entanglement of ways of being—is more useful. In an assemblage, varied trajectories gain a hold on each other, but indeterminacy matters. To learn about an assemblage, one unravels its knots.

The Mushroom at the End of the World - Anna Tsing

6 notes

·

View notes

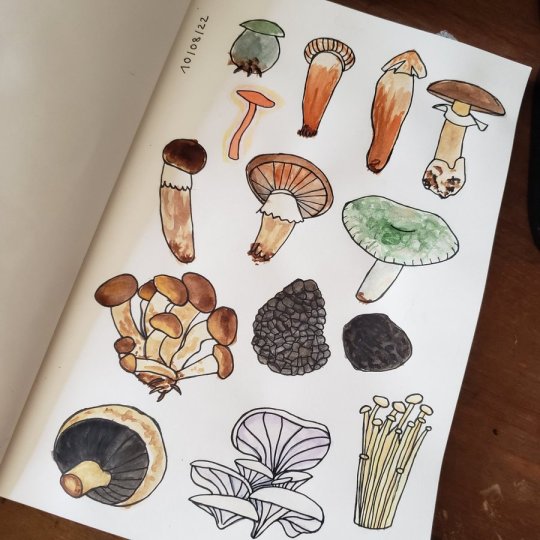

Photo

Mushroom at the End of the World

: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins

14 notes

·

View notes

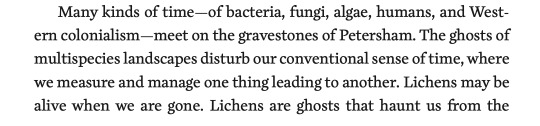

Text

—from "Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet", Introduction: Haunted Landscapes of the Anthropocene, by Elaine Gan, Anna Tsing, Heather Swanson, Nils Bubandt

0 notes

Text

HAUNTED LANDSCAPES OF THE ANTHROPOCENE

Elaine Anna Heather Nils

Gan Tsing Swanson Bubandt

What Kinds of Human Disturbance Can Life on Earth Bear?

The winds of the Anthropocene carry ghosts—the vestiges and signs of past ways of life still charged in the present. This book ofers stories of those winds as they blow over haunted landscapes. Our ghosts are the traces of more-than-human histories through which ecologies are made and unmade.

“Anthropocene” is the proposed name for a geologic epoch in which humans have become the major force determining the continuing liv- ability of the earth. The word tells a big story: living arrangements that took millions of years to put into place are being undone in the blink of an eye. The hubris of conquerors and corporations makes it uncertain what we can bequeath to our next generations, human and not human. The enormity of our dilemma leaves scientists, writers, artists, and scholars in shock. How can we best use our research to stem the tide of ruination? In this half of our volume, we approach this problem by showing readers how to pay better attention to over- laid arrangements of human and nonhuman living spaces, which we call “landscapes.” Our hope is that such attention will allow us to stand up to the constant barrage of messages asking us to forget—that is, to allow a few private owners and public oicials with their eyes focused on short-term gains to pretend that environmental devastation does not exist.

We also face a barrage of messages that tell us to keep moving for- ward, to get the newer model, to have more babies, to get bigger. There is a lot of pressure to grow.

We do not think this work is simple. It requires moving beyond the disciplinary prejudices into which each scholar is trained, to instead take a generous view of what varied knowledge practices might ofer. In this spirit, we begin with a literary essay that ofers the ine description necessary to pay attention to ruins, but later move to a scientiic report on the very long history of human-caused extinctions and an anthropological guide on how to read landscape history in the shapes of trees. These and much more open up the curiosity about life on earth that we will need to limit the destruc- tion we call Anthropocene and protect the Holocene entanglements that we need to survive.

Our era of human destruction has trained our eyes only on the immediate promises of power and proits. This refusal of the past, and even the present, will condemn us to continue fouling our own nests. How can we get back to the pasts we need to see the present more clearly? We call this return to multiple pasts, human and not human, “ghosts.” Every landscape is haunted by past ways of life. We see this clearly in the presence of plants whose animal seed-dispersers are no longer with us. Some plants have seeds so big that only big ani- mals can carry them to new places to germinate. When these animals became extinct, their plants could continue without them, but they have been unable to disperse their seeds very well. Their distribution is curtailed; their population dwindles. This is an example of what we are calling haunting.

Anthropogenic landscapes are also haunted by imagined futures. We are willing to turn things into rubble, destroy atmospheres, sell out com- panion species in exchange for dreamworlds of progress.

Haunting is quite properly eerie: the presence of the past oten can be felt only indirectly, and so we extend our senses beyond their comfort zones. Human-made radiocesium has this uncanny quality: it travels in water and soil; it gets inside plants and animals; we cannot see it even as we learn to ind its traces. It disturbs us in its indetermi- nacy; this is a quality of ghosts.

As anthropologists, we imagine our talk of ghosts in kinship with com- munities around the world, Western and non-Western, who ofer nonsec- ular descriptions of the landscape and its hauntings. Rather than an a

priori distinction between modern and nonmodern, however, we open our analysis to practical ways of learning what is out there: the past and the present around us. This book is not about cosmologies but rather about on-the-ground observations, and rom varied historical diractions and points of view. Snake spirits and radioactive clouds share our attention as each draws us closer to the haunted quality of ruined landscapes.

Our use of the term “Anthropocene” does not imagine a homo- geneous human race. We write in dialogue with those who remind readers of unequal relations among humans, industrial ecologies, and human insigniicance in the web of life by writing instead of Capita- locene, Plantationocene, or Chthulucene (see Haraway, this volume). Our use of “Anthropocene” intends to join the conversation—but not to accept the worst uses of the term, rom green capitalism to techno- positivist hubris.

As we introduce the chapters, we want to show you both their prac- tical gits for reading landscapes and their work in grasping that which is hard to grasp—the spookiness of the past in the present. In this introduction we ofer the wind as a igure for this uncanniness. Winds are hard to pin down, and yet material; they might convey some of our sense of haunting. Each paragraph in grey italics introduces an article rom our volume through its haunting qualities. (Bold phrases are key themes in direct quotation rom the essays.) We have included pieces rom the “Monsters” half of the book along with “Ghosts” since the sections tell intertwined stories. Although our analytic rames deserve some separation, monsters and ghosts cannot be segregated. Mean- while, we also use sentences in italics to index crosscurrents among our multiple authorial voices.

#anthropocene#art and ecology#ecology#climate crisis#climate change#environmental justice#environment#rights of nature#non human#animals#nature#Anna Tsing#Heather Swanson#Elaine Gan#Nils Bubandt#contemporary art#fine art#arts of living on a damaged planet#ghosts#hubris

1 note

·

View note

Photo

“we are stuck with the problem of living despite economic and ecological ruination. Neither tales of progress nor of ruin tells us how to think about collaborative survival.”

0 notes

Text

“Privatization is never complete; it needs shared spaces to create any value. That is the secret of property’s continuing theft—but also its vulnerability.”

-Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (2015)

32 notes

·

View notes

Text

got clocked right off the bat by a coworker as "really into mushrooms" and I'm still reeling from it, frankly

#we were talking about nonfiction books! and she'd read and really liked braiding sweetgrass!#and she's saying 'I really liked that it was so readable and it was about a lot of different concepts integrated together'#and I was like 'oh you should try the mushroom at the end of the world by anna tsing'#and start explaining the concept and I don't think I even really went into much detail about the mushroom itself???#just like. why it is the subject of this book and how it exemplifies the interconnectivity of environment and economics and ecology#AND OUT OF NOWHERE she's just 'I'm sensing you're really into mushrooms'#my boss fucking lost it cuz I was like 'HELLO??? MA'AM??? HOW DID YOU JUST READ ME LIKE THIS'#anyway it did remind me I wanna finish reading what a mushroom lives for which is the second book from tsing's research group#like I DIDN'T recommend entangled life cuz it was more specific and less about interconnectivity! HELLO#I have QUESTIONS LMFAO#really bewildered particularly cuz my sister thought I was only into mushrooms after I discovered I wasn't allergic to all of them#she was like 'yanno you could've just had mushrooms as a vibe before' and I was like ??? I DID???#'virtually every online friend I have associates mushrooms with me HOW have you missed this girl'#and meanwhile a coworker I've only talked to a couple times in ten minute increments identified this INSTANTLY#WHAT

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

Anna Tsing via Socialter.com

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

To live with precarity requires more than railing at those who put us here (although that seems useful too, and I’m not against it). We might look around to notice this strange new world, and we might stretch our imaginations to grasp its contours. This is where mushrooms help. Matsutake’s willingness to emerge in blasted landscapes allows us to explore the ruin that has become our collective home.

— Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

“Smell draws us into the entangled threads of memory and possibility.”

Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins

2 notes

·

View notes