#antique 1800s print

Text

Albumen print depicting a late 19th century cavalry unit on the move

#19th century#1800s#1870s#I'm guessing#uniforms#military history#horses#albumen print#one of those stunning antique photos where a modern camera could do no better

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

#19th century#photooftheday#museums#original art#horses#equine#equestrian#antique#british royal family#british art#art history#british history#unique prints#art print#wall art#wall prints#horse carriage#london#england#horse racing#horse riding#countryside#1800s#auction house#christie's#contemporary art#aquatint#colour plate

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Care to take home an old memory? 🍀

#heyo i'm selling these cat prints!#photography#antiques#vintage#victorian#cottagecore#cats#1800s#1910s#1920s aesthetic#caturday#art print#digital art#do not reupload elsewhere#but please share this post!

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Youth Playing a Lyre to a Maiden by a Fountain, 1803, Napoleonic era, Carl Wilhelm Kolbe, the elder, German (1759-1835)

Prints and Drawings

#Prints#drawings#Carl Wilhelm Kolbe#1803#lol be#art#1800s#early 19th century#1800s art#lyre#greek mythology#mythology#Ancient Greece#classical antiquity#19th century#napoleonic era#napoleonic#first french empire#french empire#plants#botany#forest#nature#scenery#German art#Germany#ruins

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

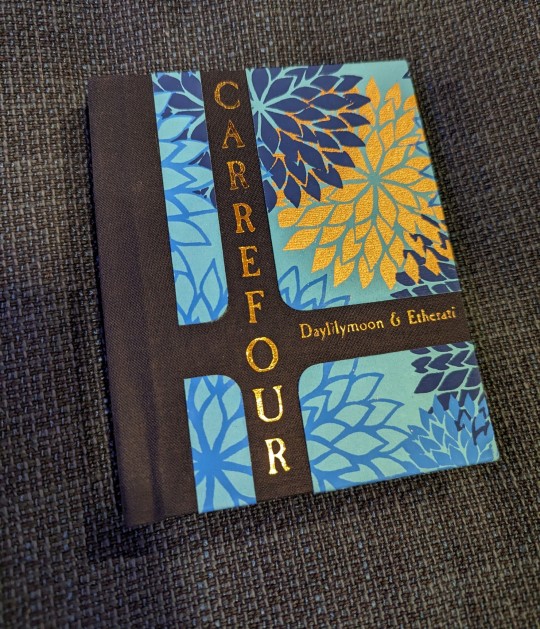

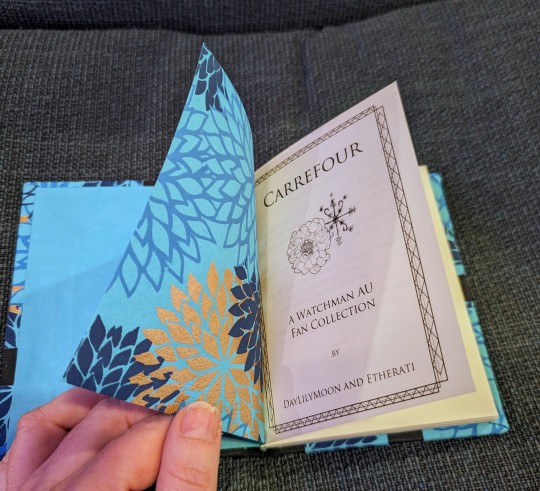

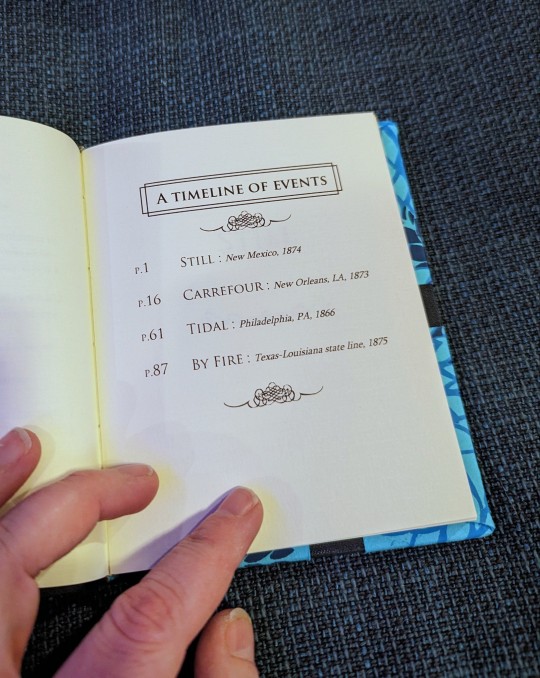

The newest quarto binding, featuring my first hand-wound headbands - the four finished stories in the watchmen Carrefour AU. Cover design meant to evoke the idea of crossroads, along with marigolds, which were an important image in the story. I wrote these collectively with Daylilymoon back in the day, and it's one of my fondest memories. Daylily if you are still around, please reach out to me, I'd love to make you a copy too--and I won't even fuck up the spelling on the spine, for your version DX

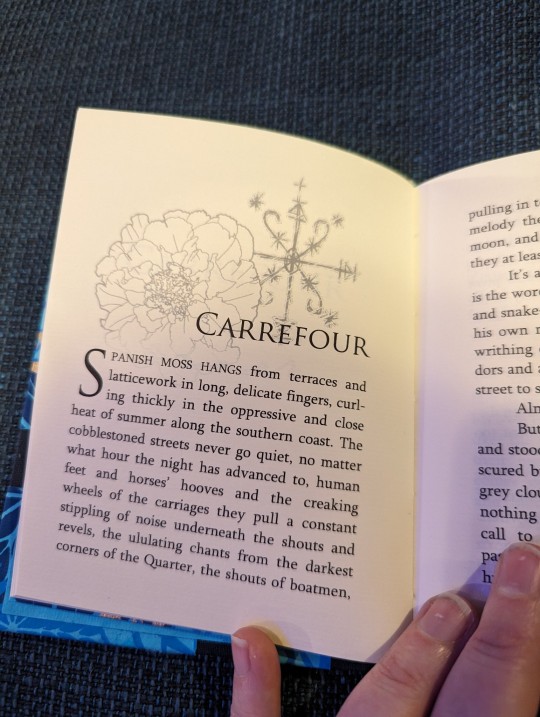

Text is Sylfean, Trajan Pro for the titles and drop caps, Caslon Antique for the cover text. Chapter header graphic and back cover version of the Kalfu veve by me. The text block was printed on some rustic, thick grain paper that I bought ages ago at Meiningers and I have no idea what the brand was, but it seemed appropriate for an 1800s era story. Cover and endpapers are art paper also from the art store. Siser metal HTV as usual.

I cannot believe I misspelled the spine, aughhhhhhhhh

#ficbinding#fic binding#fanbinding#fan binding#bookbinding#book binding#handbinding#hand binding#quarto#quarterbind#sort of

34 notes

·

View notes

Text

In February 2024, creature enthusiasts and popular media outlets celebrated what has been described as the 200-year anniversary of the formal naming of the "first" dinosaur, Megalosaurus.

There are political implications of Megalosaurus and the creature's presentation to the public.

In 1824, the creature was named (Megalosaurus bucklandii, for Buckland, whose work had also helped popularize knowledge of the "Ice Ages"). In 1842, the creature was used as a reference when Owen first formally coined the term "Dinosauria". And in 1854, models of Megalosaurus and Iguanodon were famously displayed in exhibition at the Crystal Palace in London. (The Crystal Palace was regarded as a sort of central focal point to celebrate the power of the Empire by displaying industrial technology and environmental and cultural "riches" acquired from the colonies. It was built to house the spectacle of the "Great Exhibition" in 1851, attended by millions.)

The fame of Megalosaurus and the popularization of dinosaurs coincided at a time when Europe was contemplating new revelations and understandings of geological "deep time" and the vast scale of the distant past, learning that both humans and the planet were much older than previously known, which influenced narrativizing and historicity. (Is time linear, progressing until the Empire is at this current pinnacle, implying justified dominance over other more "primitive" people? Will Britain fall like Rome? What are the limits of the Empire in the face of vast time scales and environmental forces?) The formal disciplines of geology, paleontology, anthropology, and other sciences were being professionalized and institutionalized at this time (as Britain cemented global power, surveyed and catalogued ecosystems for administration, and interacted with perceived "primitive" peoples of India, Africa, and Australia; the mutiny against British rule in India would happen in 1857). Simultaneously, media periodicals and printed texts were becoming widely available to popular audiences. For Victorian-era Britain, stories and press reflected this anxiety about extinction, the intimidating scale of time, interaction with people of the colonies, and encounters with "beasts" and "monsters" at both the spatial and temporal edges of Empire.

---

Some stuff:

"Shaping the beast: the nineteenth-century poetics of palaeontology" (Laurence Talairach-Vielmas in European Journal of English Studies, 2013).

Fairy Tales, Natural History and Victorian Culture (Laurence Talairach-Vielmas, 2014).

"Literary Megatheriums and Loose Baggy Monsters: Paleontology and the Victorian Novel" (Gowan Dawson in Victorian Studies, 2011).

Bursting the Limits of Time: The Reconstruction of Geohistory in the Age of Revolution (Martin J.S. Rudwick, 2010).

Assembling the Dinosaur: Fossil Hunters, Tycoons, and the Making of a Spectacle (Lukas Rieppel, 2019).

Inscriptions of Nature: Geology and the Naturalization of Antiquity (Pratik Chakrabarti, 2020).

"Making Historicity: Paleontology and the Proximity of the Past in Germany, 1775-1825" (Patrick Anthony in Journal of the History of Ideas, 2021).

'"A Dim World, Where Monsters Dwell": The Spatial Time of the Sydenham Crystal Palace Dinosaur Park' (Nancy Rose Marshall in Victorian Studies, 2007).

Articulating Dinosaurs: A Political Anthropology (Brian Noble, 2016).

The Earth on Show: Fossils and the Poetics of Popular Science, 1802-1856 (Ralph O'Connor, 2007).

"Victorian Saurians: The Linguistic Prehistory of the Modern Dinosaur" (O'Connor in Journal of Victorian Culture, 2012).

"Hyena-Hunting and Byron-Bashing in the Old North: William Buckland, Geological Verse and the Radical Threat" (O'Connor in Uncommon Contexts: Encounters between Science and Literature, 1800-1914, 2013).

And some excerpts:

---

When the Crystal Palace at Sydenham opened in 1854, the extinct animal models and geological strata exhibited in its park grounds offered Victorians access to a reconstructed past - modelled there for the first time - and drastically transformed how they understood and engaged with the history of the Earth. The geological section, developed by British naturalists and modelled after and with local resources was, like the rest of the Crystal Palace, governed by a historical perspective meant to communicate the glory of Victorian Britain. The guidebook authored by Richard Owen, Geology and Inhabitants of the Ancient World, illustrates how Victorian naturalists placed nature in the service of the nation - even if those elements of nature, like the Iguanodon or the Megalosaurus, lived and died long before such human categories were established. The geological section of the Crystal Palace at Sydenham, which educated the public about the past while celebrating the scale and might of modernity, was a discursive site of exchange between past and present, but one that favoured the human present by intimating that deep time had been domesticated, corralled and commoditised by the nation’s naturalists.

Text by: Alison Laurence. "A discourse with deep time: the extinct animals of Crystal Palace Park as heritage artefacts". Science Museum Group Journal (Spring 2019). Published 1 May 2019. [All text from the article's abstract.]

---

[There was a] fundamental European 'time revolution' of the nineteenth century [...]. In the late 1850s and 1860s, Europeans are said to have experienced ‘the bottom falling out of history’, when geologists confirmed that humanity had existed for far, far longer than the approximately 6,000 years previously believed to represent the entire history [...]. ‘[S]ecular time’ became for many ‘just time, period’: the ‘empty time’ of Walter Benjamin. […] The European discovery of ‘deep time’ hastened this shift. [....] Historicism views the past as developments, trends, eras and epochs. [...] Victorians were intensely aware of ‘historical time’, experiencing themselves as inhabiting a new age of civilization. They were obsessed with history and its apparent power to explain the present […].

Text by: Laura Rademaker. “60,000 Years is not forever: ‘time revolutions’ and Indigenous pasts.” Postcolonial Studies. September 2021.

---

At the time when geology and paleontology emerged as new scientific disciplines, [...] [g]oing back to the 1802 exhibition of the first Mastodon exhibited in London’s Pall Mall, […] showmanship ruled geology and ensured its popularity and public appeal [...]. Throughout the Victorian period, [...] geology was as much - if not more - sensational than the popular romances and sensation novels of the time [...]. [T]he "rhetoric of spectacular display" (26) before the 1830s [was] developed by geological writers (James Parkinson, John Playfair, William Buckland, Gideon Mantell, Robert Blakewell), "borrowing techniques from [...] commercial exhibition" [...]. The discovery of Kirkdale Cave in December 1821 where fossils of [extinct] hyena bones were discovered along with other species (elephant, mouse, hippopotamus) led Buckland to posit that the exotic animals [...] had lived in England [...]. Thus, the year 1822 was significant as Buckland’s hyena den theory gave a glimpse of the world before the Flood. [...] [G]eology became a market in its own right, in particular with the explosion of cheaper forms of printed science [...] in cheap miscellanies and fictional miscellanies, with geological romances [...] [...] or [fantastical] tropes pervading [...], "leading to a considerable degree of conservatism in the imagery of the ancient earth" (196). By 1846 the geological romances were often reminiscent of the narrative strategies found in Arabian Nights [...].

Text by: Laurence Talairach-Vielmas. A book review published as: “Ralph O’Connor, The Earth on Show: Fossils and the Poetics of Popular Science, 1802 - 1856.” Review published by journal Miranda. Online since July 2010.

---

Dinosaurs, then, are malleable beasts. [...] [T]he constant reshaping of these popular animals has also been driven by cultural and political trends. [...] One of Britain’s first palaeontologists, Richard Owen, coined the term “Dinosauria” in 1842. The Victorians were relatively familiar with reptile fossils [...] [b]ut Owen's coinage brought a group of the most mysterious discoveries under one umbrella. [...] When attempting to rise to the top of British science, it helped to have the media on your side. Owen’s friendship with both Charles Dickens and William Makepeace Thackeray led to fond name-dropping by both novelists. Dickens’s Bleak House famously begins by imagining a Megalosaurus, one of Owen’s original dinosaurs. Both novelists even compared their own writing process to Owen’s palaeontological techniques. In the scientific community, Owen’s dinosaur research was first [criticized] by his [...] rival, Gideon Mantell, a surgeon and the describer of the Iguanodon. [...] Naming dinosaurs was a powerful way of claiming ownership [...]. Owen [...] knew the power of the press [...]. [M]useum exhibits [often] [...] flattered white patrons [...] by placing them at the apex of modernity. [...] Owen would not have been surprised to learn that the reconstruction of dinosaur bones is still an act that is entangled in politics.

Text by: Richard Fallon. "Our image of dinosaurs was shaped by Victorian popularity contests". The Conversation. 31 January 2020.

35 notes

·

View notes

Note

About the Scot/scotch thing. I collect antique books and even the English preface to my antique Gaelic books printed in Edinburgh from early 1800s refer to Scots as Scotch. Definitely fell out of use in the U.K. but got preserved in the US, which seems to be a fairly common happening. Saying this as a highlander and big fan of your page :)

I’m sorry but language evolves, and an American author who has based her whole career off of ‘knowing Scotland intimately’ should know to take the L when Scottish people say we don’t like being called Scotch.

It’s up there with the pejorative use of ‘Jock’.

188 notes

·

View notes

Text

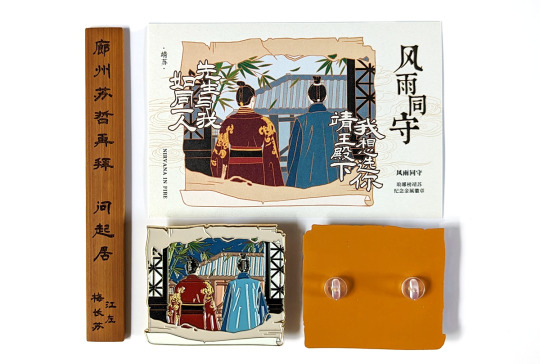

The trouble with collecting merch is it’s difficult to stop once you start. This Jingsu enamel pin is by the prolific 长风万里, who is responsible for some of the most iconic NiF pins (check out the weidian store for a partial selection). Like many fan-made pins, it’s a re-rendering of a scene from canon, in this case episode 52 [x], where Jingsu look on as thunder and wind portend the storm brewing on the horizon after Princess Liyang has agreed to present Xie Yu’s confessed crimes at the Emperor’s banquet.

The pin emphasizes the storm in both design (bamboo leaves scattering in the wind) and name: 风雨同守, loosely enduring the tempest together. As for why the image has been transposed onto a tattered scroll, the pin maker said the inspiration came from rubbings/拓印 and elaborated some more:

Personally, I think of this as an excavated artwork (with the surface damaged in its old age) that was created out of Jingyan’s longing. As if Jingsu actually existed in history and will live on for a long, long time.

我自己把这个当做是一件出土的画作(年岁久远画面有所破损),是景琰怀念所做。就好像历史上真有他们的存在,靖苏真的来日方长。

Historically, rubbings not only create an impression of existing artwork but are themselves artworks that take skill and patience. The typical process starts with adhering paper to a stone carving, then ink is dabbed to the paper such that the flat surface takes on the color of the ink while carved areas remain white (here’s a process video). Collecting rubbings was a popular pastime of the literati, and rubbings of good calligraphy were especially in demand for study and appreciation, serving a similar purpose to block printing in allowing many people to see replicas of an original. The originals may have also come from a non-stone medium: some artworks originally on paper or fabric were replicated onto stone so that rubbings could be made and collected [x]. Nowadays, ancient rubbings are valuable artifacts, especially in cases where the carving has been lost.

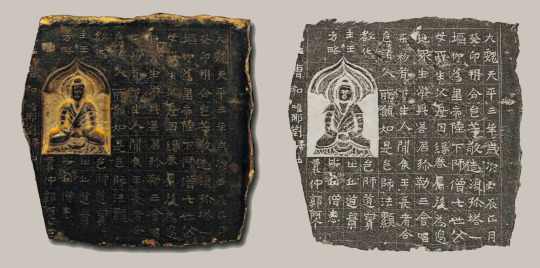

The rubbing influence is very clear in the second version of the pin, here juxtaposed against one of its inspirations:

Though the text on the right rubbing says it’s from the Tianping Era of Eastern Wei, Year 2/魏天平二年 (535 CE), which is contemporaneous with the Liang dynasty that loosely inspired the fictional NiF Liang, I couldn’t find an actual historical artwork corresponding to this rubbing, and the mass antique market is flooded with fabrications (it’s also thoroughly possible I simply failed to find the original). But here’s a real fragment of a stone Buddhist votive tablet and its rubbing that’s now at the Art Museum of the Chinese University of Hong Kong [x]:

The text says that this was made in Tianping Era, Year 3, one year after the one above, and describes the building of a Buddhist pagoda in offering, which was a common practice at the time. This monochromatic rubbing style was also quite typical; though both black ink and red ink (cinnabar-based) rubbings existed separately, they were not really seen in combination in a single rubbing until much later. What is believed to be the only surviving book of bicolor rubbings before the modern era was made in the Qing dynasty around the 1800s and was itself a copy of a lost multicolor work from the same dynasty [x].

In this context of transference of art and meaning between mediums, it’s all too easy to imagine a backstory for this Jingsu scroll: first there was a stone carving, close enough to the actual scene that the artist must have worked from Jingyan’s memory of that day. Instead of the more common approach of carving the outline or the background, the artist decided to carve the foreground so the figures were sunken into the stone. And later, a rubbing was made and mounted onto a scroll, buried and excavated, then finally rendered from fiction to reality in the form of an enamel pin. Each creation is an act of remembering and reinventing, of placing yourself in the observer’s shoes, of stoking the flames of the original story—the fire burns on through metaphorical wood replaced over the centuries, its appearance ever-changing, its core not forgotten.

That’s enough of reading too much into things—I also like the pin on its own. One thing that 长风万里 does well is not just sell pins but also communicate the entire behind-the-scenes process with the QQ group, which is several months’ worth of iterations that I find at least as interesting as the final product. For this pin, you can trace through chat logs how the pin evolved all the way from the original concept sketch to the pieces of metal that fit in your hand (thanks to 长风万里 for letting me share the draft versions here):

Once the pin maker comes up with an idea and decides to go for it, the initial sketch is given to the commissioned artist (this pin was drawn by Forwrite, on weibo and lofter) along with reference images. The artist turns these into a line drawing following the design rules of enamel pins (each block of solid color should be fully enclosed by lines, for example). Some artists will color in the line art while other pin creators commission only the line art and fill in the colors themselves. The final colors are limited to the available palette at the factory chosen to make the pins, and once the color vector art is handed to the pin factory along with instructions on detailing and finishes, the physical manufacturing process begins in earnest (this could be the subject of its own long post).

You may have noticed that there are some color changes from the vector design to the physical pins, most notably the sky in the top pin. This came about as a serendipitous accident where the factory colored the sky of the sample pin dark blue instead of the requested sunset yellow, but the pin buyers active in the group chat liked the dark blue enough that it was kept as the final color. The light grayish blue variant ended up being chosen for the backing card/背卡 instead:

Though backing cards are nominally named for their purpose in supporting the pin, practically no one sticks their pins through these cards in Chinese fandom; instead, collectors generally buy cases and books to keep each piece in pristine condition. And so unlike utilitarian cards that are meant to serve as a background to the pin, fully designed backing cards that stand on their own are very much a thing. The card also adds back in the iconic Jingsu lines that were in the original concept sketch, I want to choose you, Your Highness Prince Jing/我想选你靖王殿下 from Mei Changsu and Sir and I are as one person/先生与我如同一人 from Jingyan.

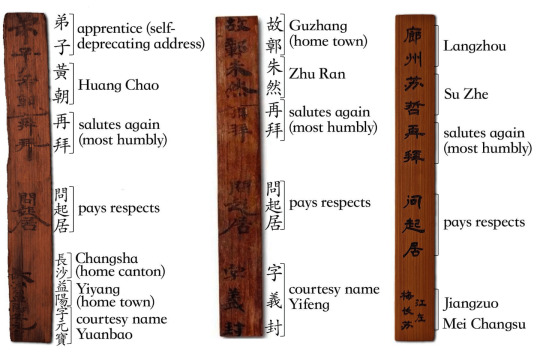

And now for the last part of the merch package that comes with the pin: the wooden piece on the left is an inscribed bamboo name slip/名刺 meant to resemble what MCS might have presented Jingyan when he visited his manor in episode 9 [x]. This was a preorder bonus to encourage buyers to get on board early, since the upfront costs to commission the artist and get a sample made at the factory are a significant portion of the overall costs (if not enough people preorder, the pin is canceled and the payment refunded, and the pin maker has to take the loss of at least the artist’s fees).

Name slips were the ancient analogs to modern business cards and an important tool of connection building in the ancient bureaucracy. The tradition of presenting a slip before you visit someone’s residence, especially if you’re lower in status than the person you’re visiting, persisted for many dynasties while the form of the slip evolved over time. Even though the visitation slip in canon appeared to be a bound paper booklet, folded books wouldn’t appear until the Tang dynasty—though paper was invented in the Han dynasty, it took time for the manufacturing process to improve sufficiently for a fundamental shift in writing mediums. Bamboo slips were what they would have used in the real Liang dynasty (plus, the modern-day replica is objectively great merch that can be used as a bookmark/fidget stick/cosplay prop/whatever else you can think of).

Slips from around the NiF time period generally stated some combination of your given name/名, your courtesy name/字, the region you’re from, and some boilerplate deferential language. Here are two real ones from Huang Chao/黄朝 and Zhu Ran/朱然 of the Three Kingdoms period next to MCS’s, with the meaning of some phrases listed in parentheses after the literal translation (using two of MCS’s names is a good solution for the lack of courtesy names in canon):

To balance out all the white background product photography, I’ll close with some texture shots:

#cost for everything was ¥90 or about $13#overseas shipping not included#先生与我,如同一人#chinese fandom#nirvana in fire#琅琊榜#merch review#long post

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

AU-gust 2023

Pairing(s): Cherik

Warnings: N/A

2. Immortals

In the six months since Erik moved to Westchester, he’d explored almost every inch of Greymalkin, from the dozens of finely furnished rooms to the surrounding acres of vast woodland that made up the Xavier estate. According to Charles, one of his ancestors migrated from England to the US in the late 1800s, and commissioned a replica of his family home to be built - almost brick for brick - on the new land he purchased. Even the furnishings had come from the original Greymalkin located in West Berkshire, which meant the house was littered with priceless antiques often centuries old. Erik had spent many a lazy afternoon roaming its halls, wondering what secrets might be revealed if one knew just where to look.

It'd been raining since Charles left that morning for the city, to take his sister Raven to their regular Sunday brunch. Erik had declined the invitation to tag along, not wanting to intrude on their well-worn tradition, but also because he sensed that Raven didn’t approve of his relationship with her brother. It wasn’t that she was rude to Erik, or that she’d been anything but unfailingly polite, but he knew enough about her from Charles to know that her treatment of him was out of character. When he asked about it, Charles had merely brushed it away, murmuring about Raven not wanting to get too attached as she’d had with some of his previous partners.

There felt like a ring of truth in what was otherwise an unconvincing lie, though Erik decided to let it go since it had little real impact on his relationship with Charles.

Since he couldn’t go for a run, he decided to try reading in the library, and while away the afternoon amongst the dusty old tomes. A copy of Brontë’s Jane Eyre happened to catch his eye, as it reminded him of his sister Ruth and how she would sometimes read to him when he was sick, or if he simply wanted a bedtime story. He remembered very little of the plot of the book, since it was so long ago, except that one of the characters had been hidden away in the attic. That train of thought led him to remember that he hadn’t explored the one upstairs, even though he’d combed through every level and every room of the giant mansion. There didn’t seem to be any reason not to check it out right now, he thought, though he realized belatedly that Charles had never actually shown him how to get up there.

Still, it didn’t take long for Erik to find the entrance, a fake bookshelf in one of the corner rooms that slid aside to reveal a hidden staircase. He’d read enough mystery and gothic novels as a kid to expect the presence of secret rooms and concealed doorways, especially in an old manor built by an eccentric millionaire. And for a passageway that likely didn’t get much use, it was clean and well lit, opening up into a giant loft space that encompassed almost a whole other level.

There was furniture wrapped under tarp, and chests of old clothes that were dated from various periods of the past century. He even found an old uniform from what he assumed was one of the World Wars, though Charles had never spoken about a family member who’d served. On closer inspection, he found a bullet hole in the material, right above the heart, and wondered whose macabre decision it was to keep the uniform. There were letters too, bundled together at the bottom of the chest, and Erik pulled the stack out gingerly, mindful of their condition.

He was stunned into silence at the picture that fell out of the first letter he opened.

It was a black and white print of what appeared to be Charles and Erik in uniform, the edges of the photo worn and faded from age. The two men were standing side by side outside the front doors of Greymalkin and grinning at the camera. The resemblance was so uncanny that Erik was almost convinced he was the person in the picture, and that he’d somehow forgotten getting dressed up and posing for it with Charles. And the man in the picture looked exactly like his Charles, with the same smile and broad shoulders and easy charm.

How was it possible that Charles had a relative who looked just like him, who also knew someone who looked enough like Erik to be his twin?

But it was not until Erik opened a second chest, and then a third that his breath caught and his heart started racing, as they were full of items – everything from old, faded photographs, pencil sketches and painted portraits, to clay masks and marble busts – bearing his face.

He shuddered, when his gaze fell on a beautiful sketch of his own profile, signed and dated by the artist:

Charles Xavier, 1458

Erik dropped the picture and ran from the attic.

#gerec writes#cherik#immortals#day 2#charles is immortal#erik is the lover he keeps finding over and over#in case it wasn't clear lol#au-gust 2023

28 notes

·

View notes

Text

WHOO!

I get to teach Forensic Sciences again next semester! With a prof I really like and have previously TA’ed for! It’s a super fun course - Intro to Criminalistics - so it’s a little bit of everything. Prints, bones, blood, DNA, drugs, mapping, and more. She’s also researching Forensic Anth, so we can dork out about bones.

AND I’m teaching Crim Theory, too, which is a designated writing-intensive course. I have not worked with the prof for this course, but I hear she’s awesome. Not only do I get to dive into the history of Criminology again, but go absolutely ham on essay-writing technique and tips. (YOU WILL LEARN TO STACK AN ARGUMENT. I can’t guarantee you will learn to love APA, but you will come to grips with it and develop a personalized checklist with samples of in-text citations and title page contents, in order.)

Lesson 1: Who Are You? (Who who? Who who?)

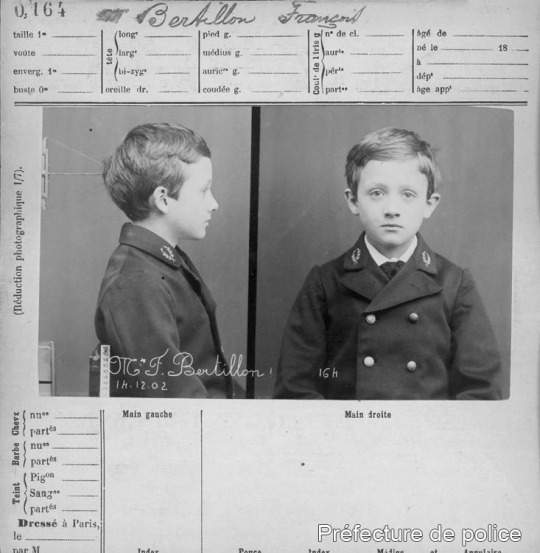

[Text ID: An antique parody of a double mug shot, in sepia tones. A 23-month-old infant with curly light hair sits in a plain wooden high chair, a winsome expression on his face. He is dressed in a typical child’s white frock of the period with a frilled collar, sleeves and skirts. The first panel is in profile, with the child facing right. The second panel is face-on. The inscription reads: François Bertillon, âgé de 23 mois. 17 - oct - 93.]

This infantile mug shot, now in the MOMA collection, is commonly known as: “François Bertillon, 23 months (Baby, Gluttony, Nibbling All the Pears from a Basket)”

Alphonse Bertillon, a French police officer from the late 1800s, sought to revolutionize criminal identification by statistical means. He developed a system, which he called Bertillonage, of body measurements - anthropometry - that could be tabulated and compared with others, under the assumption that no two people would share the exact same measurements.

Now, this idea was an offshoot of biological determinism, a theory that the body itself predicted behaviour and the state of the mind. Biological determinism was actually a revolution in its day: it represented a split from the previous belief that aberrant behaviour and physical infirmity were proof of demonic influence and a directly-involved God. However, biological determinism, itself an offshoot of Platonic essentialism, led to such notions as Lombroso’s “atavistic”-bodied criminal with a hulking body, a lowered brow and a “stupid stare”, as well as pseudo-science parlour fun like phrenology. Not to mention the blatant eugenicism and superior-more-developed-race blather that still persists in many branches of social sciences.

But two hundred and some years into the European Enlightenment, empirical science was moving slowly towards the acceptance of provable, testable hypotheses based in reason and repetition. So Bertillon reasoned that, if you went about the task scientifically, with enough detail, you ought to be able to prove that no two people had the same bodies, and could therefore be told apart. (And just maybe prove that you could tell a criminal from looking at them.)

But no. The collection of Bertillonage data was incredibly painstaking. Subjects had to have a long series of measurements taken, in the exact same postures, using the same equipment. Then, the subjects were required to have photographs taken, from specific angles: the first mug shots. Bertillion spent years perfecting his photographic system. The above photos of his little nephew François are just one example of Bertillon bringing his whole family into the process - an excuse to combine his work with his hobby of photography and his love of his close-knit family.

(Note the implication here: “My family is the control group, the ideal specimens. Normal people look and behave like us.” When thinking about data, always ask yourself: who’s taking the photographs? Who’s collecting the samples, and from where, and how, and why those samples in particular?)

Bertillonage didn’t take off. People have too many similarities as well as differences, and the human error involved in the measurements and photography was too great. But he did create a stunning longitudinal study of his family and friends over a couple of decades, as well as of local criminals. Here’s François a few years later. Can you see details that persist through out his aging? How would you describe them?

You can see here some of the prescribed measurements in the Bertillonage system - and they didn’t have spreadsheets to look up and compare cases!

Bertillon’s underlying idea had merit. No two people are exactly alike. Even identical twins develop epigenetic differences over time. Fingerprints form in the womb, with randomized development due to the uterine environment. We can only measure these things with technical tools - low tech like magnifying glasses, high tech like digitized pattern recognition and molecular amplification. But we’ll get to that later.

Before you leave! Your homework this week is to write a description of yourself that is detailed enough that it would help investigators identify your remains. Under 500 words please. Point form is fine. Post to Canvas by midnight Sunday.

23 notes

·

View notes

Note

I loved the talk you gave at BarricadesCon, your pictures and information were so good! I was curious to hear more about underwear and canon era if you feel like going into it? I've been largely working off fandom sources, and I'd gotten the impression that women in the '20s and '30s might or might not wear drawers, but that men would by and large have used their long shirts as their only undergarment. It sounds like you know otherwise, and I'd love to hear more if you feel like elaborating.

Thank you!

Women's clothes are more my area of focus than men's, but here's a quick run-down. I'll try to follow up with more citations when I have some spare time.

The short version is that we have both surviving garments and text sources for men's drawers/underpants during the late 18th century and first decades of the 19th. We also have reports that some men did not wear them. It is possible to tuck the long tails of the shirt so that they do the job of drawers. It is also reported that some pants had removable (washable) linings, which would be very helpful in this case.

In Shaun Cole's "The Story of Men's Underwear", the author notes not only the presence of linen drawers in men's clothing inventories of the late 18th and early 19th century (most with 3-4 times as many shirts) but also quotes from a biographer of Beau Brummel that highly fashion men such as Brummel, Scrope Davies, and Lord Byron would forego drawers in order to keep the lines of their trousers right.* [pg 50, see all of chapter 2 for fun times with 19th century shirts] I personally know people who did this is in the 2000s for the exact same reason, but I still take any secondary source commentary on Beau Brummel with a very large grain of salt.

The Victoria and Albert Museum's "Four Hundred Years of Fashion" [pg 61-62] describes a man's wardrobe which the museum received. Among of the clothing owned by Mr. Thomas Coutts (d.1824) were 46 shirts and 57 "items of underwear made of either linen or wool".

You can see some of them here:

Baumgarten & Watson's "Costume Close-up" is focused on the late 18th century, but does include a note on page 110 stating that many men did use their shirt-tails in place of drawers. Though no individuals are singled out as examples, several exceptions are named: George Washington (who apparently instructed his tailor to cut his breeches so that they fit over drawers--which says something about either the common practice or his tailor's idea of ease), Thomas Jefferson (who apparently got cold easily and had many undergarment and under-layers in his clothing inventories), and Royal Governor Lord Botetourt (who also had drawers in his inventory). This commentary is framed around a description and pattern draft of a pair of antique French drawers dated 1750-1800 in the Williamsburg collection.

Shelley Tobin's "Inside Out: A Brief History of Underwear" quotes from a 1790 source which states that "drawers were not worn", but interprets this as only applying to children's clothes. It goes on to cite a 1780 inventory which includes linen, leather, and flannel drawers owned by an adult man. [I don't recall seeing any other references to leather drawers, but chamois leather does appear in 18th/19th century undergarment contexts, particularly for garments that will be subject to abrasion. I suspect these drawers were meant for riding.]

Moving from the secondary printed sources to the primary, the 1838 Workwoman's Guide states that trowsers or drawers "are worn by men, women, and children of all classes, and almost all ages", and goes on to give patterns and diagrams for making them.

65 notes

·

View notes

Text

Near the beginning of this year, I made an interesting discovery at a rural antique shop: an early 20th century glass slide projector. What really caught my eye though was the lens attached to the front of it.

This lens:

This was clearly not the original lens for this projector. It is, in fact a much earlier lens. A large format portrait lens from the mid-1800's. Some research on the internet revealed that it was almost certainly manufactured in between 1848 and 1851 (most likely 1850), but it is hard to find specific records from a 19th century German manufacturer.

That was going to be the end of it; a neat thing I saw in an antique shop, but didn't buy. Then, a strange confluence of events: a close friend who works a a second hand and salvage shop let me know that they'd just received a pair of large format cameras (sans lenses or film holders). And I could have one for the princely sum of $25US.

So I picked one up - a 4x5 view camera with intact bellows and ground glass. So then I need to find a lens for it. Like, I dunno, a mid-19th century portrait lens. So my wonderful partner decides to contact the antique shop to see if the projector is still available, and arranges to buy it.

So now I have a long term project of rehabilitating a large format camera and restoring a very early photographic lens.

The projector turns out not to be in super great condition. It has some neat parts intact, but the bellows and the lamp housing are in pretty rough shape.

The lens has one major modification likely made in the early 20th century (perhaps when it was being mounted to the projector); the original focusing mechanism was disabled and the lens barrel was cut to enable a crude twist-to-focus action. Apart from that, it seems to be in ripe condition for a clean up and restoration.

I've got the glass cleaned up now, and still need to clean up the brass and reassemble it, then figure out how to 3d print some parts to mount the lens to the camera and create a film holder to do some photography with it.

#photography#large format photography#petzval#voigtlander#Petzval was a bit of a jerk but Voigtlander was a thief

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Antinous / Hermes de Pio-Clementino

Desmet Galerie

Antinous / Hermes de Pio-Clementino

Period:

17th century

Provenance :

Ital

Medium :

Wood

Dimensions :

l. 15.75 inch X H. 51.18 inch X P. 15.75 inch

Height: 130 cm

W x D: 40 x 40 cm

H 51 1/8 x W 15 3/4 x D 15 3/4inch

The statue shows a nude young man with a cloak ‘chlamys‘, thrown over his left shoulder and wrapped round the left forearm. He is standing at rest in a contrapposto pose gazing downwards.

The statue is made out of a soft wood and was originally covered in a layer of stucco, which would have been painted most likely in white to imitate marble. With the stucco surface gone, we can beautifully see how the statue was made. The body was carved out of one piece of wood and the head and arms were attached separately to make it easier for the sculptor to work.

The purpose was to make it look like a heavy marble classical statue. The white surface would cover any restorations, imperfections and from a distance it would have been impossible to see the difference. An added bonus was the weight of the soft wood; it could be placed on a lighter structure made of a different material than stone or marble.

Taken in consideration the material used and the technique of sculpting, it is not such a far stretch to imagine it on top of a balustrade in a Renaissance theatre. The best comparable is the Teatro Olimpico in Vicenza (1580-1585). It was designed by Andrea Palladio and it is today one of the three Renaissance theatres remaining in existence. (the other two being the Teatro all’antica in Sabbioneta and the Teatro Farnese in Parma).

The ancient Roman statue is also known as the l'Admirable, Admirandus, L'Antin, Hercules, Meleager, Mercury, Milo and Theseus.

It was apparently recorded for the first time on 27 February I543 when a thousand ducats were paid to 'Nicolaus de Palis for a very beautiful marble statue ... which His Holiness has sent to be placed in the Belvedere garden'. By April I545 it was certainly in the statue court. Writing a few years later Aldrovandi said that it had been found 'in our time' on the Esquiline near S. Martino ai Monti, but Mercati in the 1580s said that it had come from a garden near Castel S. Angelo- where the Palis family seems to have owned property. It remained in the statue court until 1797 when it was ceded to the French under the terms of the Treaty of Tolentino. It reached Paris in the triumphal procession of July 1798 and was displayed in the

Musée Central de Arts when it was inaugurated on 9 November 1800. It was removed in October 1815, arrived back in Rome on 4 January 1816, and was returned to the Belvedere courtyard before the end of February.

The statue won immediate fame and it was already known as Antinous (a title frequently given to figures of male youths) in 1545 when Primaticcio, on his second visit to Rome from Fontainebleau, had a mould made from it for François Ier. Alternative theories that it might represent Milo or the Genius of a Prince were suggested not long afterwards but won little support. The Antinous was mentioned with enthusiasm in virtually all accounts of the most famous statues in Rome. It was reproduced in all the leading anthologies and was also much drawn by visiting artists. It was copied both in marble and in bronze and in rare occasions in wood, as we can see here. In the catalogue of the sculptures of the Musée in Paris it was described as 'one of the most perfect statues that has come

down to us from antiquity - an opinion that continued to be very widely held for most of the nineteenth century.

Moreover, the Antinous was as popular with artists of all persuasions as it was with collectors and connoisseurs. Bernini was as enthusiastic as Duquesnoy and Poussin who (possibly with the assistance of Charles Errard) made measured drawings of it which were reproduced in Bellori's Lives of the Modern Painters, Sculptors and Architects. Two more measured engravings were published by Audran in his prints, made for the use of artists, on the proportions of the ideal human body, and in his portrait of Charles Lebrun (now in the Louvre) which Largillière presented to the Académie Royale de Peinture et de Sculpture in 1686 a reduced version of the Antinous (and also one, in bronze, of the Borghese Gladiator) was prominently displayed in front of the president's easel. Nearly seventy years later in his Amalysis of Beauty Hogarth (who, of course, never saw the original) claimed that in regard to the utmost beauty of proportion' it is allowed to be the most perfect of any of the antique statues'.

Before he saw the marble itself Winckelmann agreed that 'our Nature will not easily create a body as perfect as that of the Antinous admirandus'. He expressed passionate admiration of the statue for its sweetness and innocence of expression which, following a critical commonplace, he contrasted with the godlike majesty of the Apollo nearby. It was Winckelmann, however, who challenged the theory that the statue portrayed Antinous, suggesting instead, with not much force and with no evidence, that it was a Meleager.

A number of alternative hypotheses were also made. Mengs proposed verbally that it was a beardless Hercules; for others it was a Theseus; while Visconti (who greatly admired the figure) produced a strong case, which won general acceptance in his own day and has retained it ever since, that the Antinous was in fact a representation of Mercury, as had been proposed much earlier by Stosch and rejected by Winckelmann. Visconti's most cogent argument depended on the existence of another version of the same figure wearing winged sandals and holding a caduceus. This version (since 1546 in the Farnese collection and acquired for the British Museum in 1864) had been noted without special enthusiasm by some writers and draughtsmen since the sixteenth century, but it seems not to have been related to the Belvedere Antinous before the Richardsons: they, however, accounted for the fact that it was "the very same Figure on the grounds (which they

deduced from numismatic evidence) that Antinous was sometimes identified with Mercury. By the end of the nineteenth century, however, it was the Farnese statue in the British Museum which attracted most scholarly attention, but this in turn was eclipsed by the replica found at a tomb in Andros (now in the National Museum in Athens). Some scholars consider that these statues are copies of a work by Praxiteles, but the Belvedere Antinous is catalogued in Helbig as a Hadrianic copy of a bronze original possibly by one of his pupils.

Provenance:

Our provenance goes back to when it stood in the historic Chateau de la Crois des Gardes, “the jewel of the French Riviera”. this legendary Belle Epoque property is an homage to the glory days of the French Riviera. Legend has it that Grace Kelly immediately fell under the spell of this unique castle, positioned a few minutes from the port of Cannes.

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

i have... a penchant... for getting really into books which are out of print. not cause they’re like first editions or collectibles or whatever the fuck (i went to an antique book show recently and was SO pissed there was like 50 Alice in Wonderlands, but no 1900 printed french books you couldn’t even find in pdfs online... in fact, no foreign language books at all what the fuck :c... and 2 gone with the winds, 50 lord of the rings... like i get it, the target audience of an antique show is maybe? idk people collecting expensive books? but for me? the point was to find out of print old books that may never have been digitized. thank the universe for archive.org there’s so many 1800s learn japanese, 1900s learn chinese books with different versions of romanization and then later different amounts of character simplification, theres the ‘nature method’ textbooks that i’ve only seen back in print very recently and only for a few languages and probably only cause nerds like me can’t shut up about them, there’s so many BOOKS i’m into that just... :c good fucking luck finding them if not for the kind efforts of archivists or random chance)

#rant#like. god even kamikaze girls??? a RECENT novel. a novel with a MOVIE#and its like... seems to have only had one print run or whatever#u can find it used. sometimes. thats it#and like ive been trying to find novalas other novels? hhaha i cant even find them used. they're out of stock.#and then like. there's this AMAZING japanese book called Japanese in 40 Hours.#a HERO made a video series of the chapters on youtube i recommend looking at it. and its on archive.org thank fuck#but its basically i think the BEST sparksnotes basic primer for western speakers to begin learning japanese#its quick. it gives a solid foundation of grammar and word endings before throwing u into kana. and its faster paced then a LOT of modern#books ive used.#theres a chinese book called Chinese Grammar by the Nature Method.#i believe the author is Thimm. it was published in like 1929. it is all#traditional characters. its like 300 very compact pages. its a very beautiful small book.#it has a HUGE hanzi dictionary in the back. it is THOROUGH in its grammar explanations and SO easy to understand.#its my favorite chinese grammar book by far. and the sheer VOLUME of words in it#make it a good overall book#not just for grammar but also words. the only weird thing is the old romanization system but once u recognize the hanzi u can#match them to modern pinyin you know better. and just? it is SUCH a good book#even with the outdated bits (like NIN used a lot and le pronounced liao in a lot of spots we'd now use le)#and its out of print. its another book i think i found on archive.org then wanted a print copy of

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sometimes I just have to stop and sit down and reflect on the things this one particular book I own has been through. It’s only forty years old, but it has seen some life.

Specifically, said book is the 1983 edition of the United Kingdom’s Norwegian Buhund National Club Stud Book. It’s literally a maybe hundred page book containing photographs and three generation pedigrees of the couple dozen Buhunds that lived and actively showed in the U.K. at the time. It’s a mint green paperback book that was thrown together as cheaply as possible, probably cost about five pounds for a copy if I had been after it in 1983.

By the time it reached my hands, it was already worn on the spine and has at least eight different stains in them. Some are coffee, some are tea, maybe one or two are water. They’re old enough to no longer hold the scent of what made those stains, but they’re noticeably _something._ Someone, at some point, spent some time pouring over and memorising the family trees of a bunch of sunshiney little spitzy dogs, just as I do now, today, in the next century over.

At some point, that book ended up in a box, and it was donated to a used bookstore. Or maybe sold, I don’t know. This book, printed in Lancashire thirty-nine years ago, found its way into a used book store with no hint of who its previous owner was apart from the note in the inner binding that says “Hygge’s grandfather is on page seventy-eight! That’s who gave him his quirkiness!”

Who is Hygge. What quirks did Hygge’s grandfather have? All I know from this story is Hygge’s grandfather is a particularly handsome wheaten Buhund named Abu, who was the son of Olaf and Polly Perkins, children respectively of Trump, Fanna, Snorre and Pensive. Cross referencing those pedigree names with a few different pedigree databases tells me Abu sired 28 Buhund puppies across eight litters. Who, in turn, sired or damed an additional two hundred puppies. And that’s just accounting for registered pups. I can’t find one two generations down from Abu named Hygge, but maybe someone’s Buhund bred with a different breed, and there was some Buhund mix out there named Hygge whose owner loved him so deeply they requested some information about where he came from. I don’t know. I can’t confirm that, but its wonderful to think about that hypothetical dog named Hygge who was, along with his mysteriously vague “quirks,” very loved by someone.

Sometime after this book, somehow, left the hands of Hygge’s owner - maybe they passed away, and their books got lotted up into a thrift store? Maybe they changed hands a few times? It wound up in a store in York. I have no way of knowing how long ago it arrived at that shop, only the listing for the book itself was posted on AbeBooks in 2016. Four years before I saw it, myself.

Including shipping, I paid $54.38 to have this book wrapped up and sent to me in America. Three months passed, and I still hadn’t gotten that book in the mail. I reached out to the bookstore itself, and asked if there was a problem, only to find out the store’s previous owner had unexpectedly passed away a few weeks prior and it was still being sorted what was going to happen to all of these books, as he had neither any staff nor family to take over the shop. My reaching out to them let them know that there was an AbeBooks account to check for orders, and it got a ton of that shop’s books sent to where they needed to go. I received not only the studbook, but a whole box of dog books - antique training guides written in the late 1800s, a couple mid-2000s trick idea books, picture books featuring currently recognised breeds, and I cherish each and every one of these books/

But not one of them is as clearly, personally loved as that 1983 Buhund Studbook.

I added my name, where I bought it, and when I, eventually, have a Buhund of my own, I’m going to paste a picture of them into the blank Notes section in the back of the book. And when I pass away? I want that book to go to someone else who also loves Norwegian Buhunds, and I want that stranger’s love of Hygge to be known to someone else.

#flying false colours ;; ooc#fuck im emotional#who let me fall in love with this breed#who let me pour everything i learned about researching hsitory into researching Buhunds#i NEED to share these emotions with someone and the dash is going to read this#maybe

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

Check out this listing I just added to my Poshmark closet: Antique Vintage Flower Print Edwardian Long Sleeve Top Blouse Cotton.

0 notes