#artiopoda

Text

Although Triopus draboviensis here might look like an isopod or a trilobite, this small arthropod was actually part of a rather rare group called cheloniellids.

Known from the early Ordovician to the early Devonian (~480-408 million years ago), only about 7 different species of cheloniellid have been described so far. Their evolutionary relationships were uncertain and controversial for a long time, but currently they're thought to be distant cousins of trilobites within the Artiopoda.

Living in what is now Czechia during the late Ordovician, about 460-450 million years ago, Triopus is only known from two partial fossils. It was around 4cm long (~1.6"), and like other cheloniellids it had a body made up of wide radiating exoskeleton segments that fully covered its legs, and probably also a pair of whip-like appendages at the rear.

Its body was more domed than those of its relatives, who were generally very flattened, suggesting it was specialized for a slightly different lifestyle or habitat. Without any preserved appendages it's not clear what its ecological role was, but since other cheloniellids had horseshoe-crab-like feeding structures it may have been a similar sort of generalist, preying on small invertebrates and scavenging carrion on the seafloor.

—

NixIllustration.com | Tumblr | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#triopus#cheloniellida#vicissicaudata#artiopoda#arthropod#invertebrate#art#fake isopod hours

247 notes

·

View notes

Text

isopodcouture -> artiopoda

(what's artiopoda?)

#FORK YEAH SORRY EVERYBODY WHO VOTED WEEVILFAG#objectively. still a banger url. probably a better url#but trilobites...............

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Early Marine Life in the Shallow Seas — The Trilobite Age

Early Marine Life in the Shallow Seas — The Trilobite Age

View On WordPress

#Artiopoda#Cambrian#Dikelocephalus#Environment#Geological history of Earth#Geological periods#Human Interest#Marine life#Paleozoic#Shallow Seas#Trilobite

0 notes

Text

Strange Symmetries #06: Trilobite Tridents

The genus Walliserops was one of the weirdest-looking trilobites, covered in numerous pointy spines and sporting a large three-pronged "trident" on the front of its face.

They also had some degree of asymmetry in their bodies. Their tridents often didn't fork evenly, and their long forehead spines curved off to one side – possibly so they could lift their heads up without stabbing themselves in the back.

Walliserops hammii lived in what is now Morocco during the early-to-mid Devonian, about 403-392 million years ago. Around 5cm long (~2") It was one of the "short trident" species of Walliserops, and its chunky forehead spine curved particularly strongly to the right.

The function of these trilobites' elaborate tridents is still poorly understood. But an unusual individual of the long-tridented species Walliserops trifurcatus has been found with a lopsided four-pronged trident, and since it was able to grow to full maturity the shape of the structure probably wasn't absolutely vital for survival, suggesting it wasn't used for feeding or sensory purposes.

The tridents may instead have been used for combat with each other similar to the horns of some modern beetles. However, these sorts of features are usually only seen in males, and there's currently no definite evidence for any significant sexual dimorphism in trilobites.

(Although perhaps like ceratopsid dinosaurs their ornaments were just present in both males and females, being also useful for species recognition, visual display, and defense against predators.)

———

NixIllustration.com | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#strange symmetries#paleoart#paleontology#palaeoblr#walliserops#phacopida#trilobite#artiopoda#arthropod#invertebrate#art#that is an excellent snoot#go home evolution you're drunk#trilobites that trilo-fight

218 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cambrian Explosion #54: Trilobita – Transform and Roll Up

Most trilobites were able to roll themselves up into a protective ball – a behavior known as enrollment or volvation – exposing just their heavily armored backs to attackers. They're often found fossilized curled up like this, and rare preservation of soft tissues shows that they had a complex system of muscles to help them quickly achieve this pose while simultaneously tucking their antennae and all their limbs safely inside their enrolled shells.

Some species also developed sharp defensive spines and spikes that jutted out when they enrolled, making themselves even more daunting to potential predators in one of the earliest known examples of an evolutionary "arms race".

———

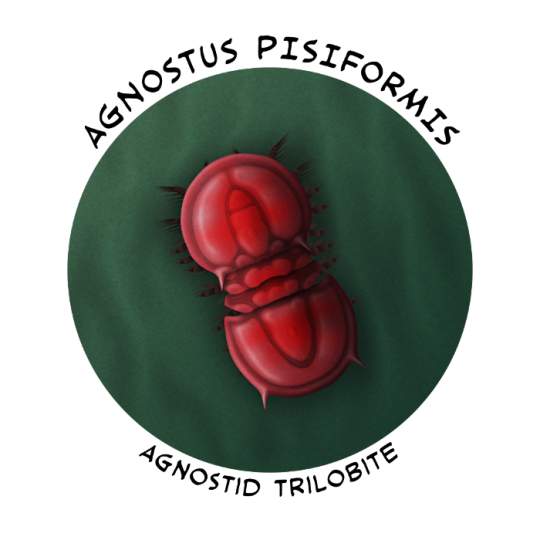

The agnostids were a group that first appeared in the early Cambrian very soon after the redlichiids and ptychopariids, and lasted until the end of the Ordovician about 444 million years ago. They probably evolved from some of the first ptychopariids*, and were highly specialized compared to other early trilobites, with large head and tail shields that usually looked almost identical, sometimes lacking eyes entirely, and only having two or three thorax segments – showing some convergent similarities to their nektaspid cousins.

( * There's been some debate about whether agnostids are actually trilobites, or whether they're closely related "trilobitomorph" artiopodans or even stem-crustaceans that just happened to somewhat resemble trilobites. This is due to soft-tissue preservation revealing limb anatomy that was very different from trilobites and looked more like the legs of crustaceans. But despite some other oddities, like having six pairs of head appendages instead of trilobites' usual four, the rest of their anatomy still places them firmly as artiopods, and as either trilobites or almost-trilobites.)

Found all around the world mainly in deeper-water environments, agnostids probably spent most of their time crawling around on the sea floor, but they may also have been able to swim in a semi-enrolled posture. They're also sometimes found preserved sheltering inside the empty hard parts of other animals, such as hyolith shells or Selkirkia tubes.

Some agnostid fossils have been found clustered in large numbers around the remains of other animals, suggesting they may have been opportunistic predators and scavengers, sometimes even cannibalising each other.

Agnostus pisiformis was a typical member of this group, known from the mid-to-late Cambrian (~506-492 million years ago) from sites including Sweden, Siberia, England, Wales, and Canada – widespread and common enough that it can be used as an index fossil to help date rock layers.

It grew to about 1cm long (0.4"), and while its front and back ends looked very similar the tail shield can be identified by a small pair of spines on its outer edge. Despite having only a couple of articulated body segments to work with it was capable of rolling up so its head and tail shield met and fully enclosed its body, forming a pea-sized protective capsule.

———

The corynexochids were another major group of trilobites to appear in the early Cambrian, descending from early redlichiids. They were one of the longest-lived trilobite lineages, lasting until the late Devonian about 376 million years ago, and often had large tail shields and spines adorning their bodies.

Olenoides nevadensis was a fairly rare species of corynexochid, known from the Wheeler Shale (~507 million years ago) and Marjum Formation (~505 million years ago) in Utah, USA

Up to about 5cm long (2"), it was very spiky for a Cambrian trilobite, with long "cheek" spines, pointy side lobes on its body segments, a row of spines along its back, and four pairs of spines on its tail shield. Like some other early trilobites it wouldn't have quite been able to roll into a tight ball, instead forming more of a "cylinder" – with its bristling spiny segments protecting its partially-exposed sides, and its tail shield lining up with its head to present an intimidating row of spikes.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#cambrian explosion#cambrian explosion 2021#rise of the arthropods#agnostus#agnostida#olenoides#corynexochida#trilobita#trilobite#artiopoda#euarthropoda#arthropod#panarthropoda#ecdysozoa#protostome#bilateria#eumetazoa#animalia#art#enrollment#volvation

133 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cambrian Explosion #53: Trilobita – A Prolific Paleozoic Posse

The biggest stars of the Cambrian euarthropods, and most of the Paleozoic Era, were of course the trilobites. Known from literally tens of thousands of species spanning over 270 million years, they're some of the most recognizable and popular fossils.

Trilobites' exact evolutionary origins and transitional forms are unknown, but they're thought to have originated in Siberia in the very early Cambrian and their leg anatomy indicates they were a part of the artiopodan lineage. They made a sudden and dramatic entrance to the fossil record about 521 million years ago, appearing fully-formed and rapidly diversifying and spreading all around the world within just a couple of million years.

Their hard calcified exoskeletons made them much more likely to fossilize than soft-bodied animals, with a distinctive three-part body plan consisting of a head shield, three-lobed thorax segments, and a tail shield. Each individual regularly molted their carapace throughout their life, meaning that most trilobite remains are actually empty discarded shells rather than actual carcasses.

Along with being heavily armored arthropod tanks, most species were also able to roll themselves up to defend against predators, and some developed additional elaborate spines and spikes.

…And some were just weird.

Many trilobites had well-developed complex compound eyes with crystalline lenses (and some had elaborate "hyper-compound eyes"), but much of the rest of their anatomy is still poorly known, with only about 21 species found with preserved soft body parts. We do know they had a pair of antennae, biramous limbs with walking legs and feathery gill branches, and at least one species had a pair of cerci at its rear end, but there was probably a lot of soft-part diversity in this massive group that we'll just never know about.

I could easily spend entire months on trilobites alone, but there's still a handful of other major groups of Cambrian arthropods to get through as we head towards the final week of this series. So we only really have time for the barest glimpse at their ridiculous variety.

———

Some of the very earliest trilobites were the redlichiids, which ranged from about 521 to 500 million years ago during the early and mid Cambrian. They were more of an an "evolutionary grade" than a distinct lineage, giving rise to several other major groups during their time.

They were mostly fairly "standard"-looking trilobites with flattened bodies, although some had long spines or unusually large numbers of segments – up to 103 in one species.

Kleptothule rasmusseni was one of the odder-looking redlichiids, found in the Sirius Passet fossil deposits in Greenland (~518 million years ago). About 3cm long (1.2"), it had an elongated and relatively thin many-segmented body and a pointy head, giving it an almost snake-like appearance.

———

The ptychopariids were another very early group of trilobites but were somewhat longer-lasting, surviving until the end of the Ordovician about 444 million years ago. Much like the redlichiids they were more of an "evolutionary grade" splitting off various other major lineages during their existence – including the proetids, the group that eventually became the last trilobites to ever live at the very end of the Permian.

They were also fairly standard in appearance (with a few eyeless forms and odd exceptions), but they also include one of the most common and familiar trilobites in the world: Elrathia kingii.

Up to around 5cm long (2"), this trilobite is known from massive numbers of specimens (possibly in the millions) from the Wheeler Shale in Utah, USA (~507 million years ago). It had a wide thorax and short spines on the "cheeks" of its head shield, and seems to have been unusually tolerant of low oxygen conditions on the seafloor. It was one the earliest known animals to exploit such an environment, avoiding predators and competition, and it probably either grazed on sulfur-oxidizing bacteria or had evolved a symbiosis with them similar to modern giant tube worms.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#cambrian explosion#cambrian explosion 2021#rise of the arthropods#trilobite#kleptothule#redlichiida#elrathia#ptychopariida#trilobita#artiopoda#euarthropoda#arthropod#panarthropoda#ecdysozoa#protostome#bilateria#eumetazoa#animalia#art#so many trilobites

128 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cambrian Explosion #52: Artiopoda – Who Needs A Thorax Anyway?

The nektaspids were one of the most unique-looking groups of artiopodans, with soft-shelled unmineralized bodies, no eyes, and large head and tail shields with very few actual body segments in between – varying from 6 all the way down to none at all.

First appearing in the fossil record around 518 million years ago, only a few different species are known but they appear to have been abundant animals distributed in outer shelf waters worldwide during the Cambrian.

Their classification has traditionally been uncertain but specimens with well-preserved limbs show very trilobite-like leg anatomy, helping to place them in the artiopodans as potentially some of the closest "trilobitomorph" relatives to the actual trilobites.

———

Naraoia compacta was one of the nektaspids with no thorax segments at all, having a semicircular head shield and a large oval tail shield. Up to 4cm long (1.6"), exceptional soft-part preservation shows it also had sideways-pointing antennae and biramous limbs with large paddle-like gill-fringed flaps.

It's known from various Cambrian sites around North America, most famously the Canadian Burgess Shale deposits (~508 million years ago). Additional fossils from the similarly-aged Chinese Kaili Biota and the older Australian Emu Bay Shale (~514 million years ago) represent either even more occurrences of Naraoia compacta or a very similar closely related species in the same genus.

It was probably a bottom-dwelling animal, possibly a burrowing deposit feeder eating organic matter in seafloor mud.

One Australian Naraoia specimen shows some of the earliest direct evidence of predation in the fossil record, with a distinct bite taken out of the carapace – thought to have been inflicted by a large radiodont.

———

The evolutionary relationships of Aaveqaspis inesoni are unclear, but its general body shape suggests it may have been one of the few-segmented nektaspids.

Known from the Sirius Passet fossil deposits in Greenland (~518 million years ago), it was about 2.5cm long (1") and had a trilobite-like shape with an eyeless semicircular head shield, five thorax segments, and a tail shield bearing two huge backwards-pointing spines.

———

Nektaspids were a surprisingly long-lived group of non-trilobite artiopodans, surviving through multiple mass extinction events and lasting at least until the late Silurian about 420 million years ago. The last known member was another Naraoia species in North America, Naraoia bertiensis.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#cambrian explosion#cambrian explosion 2021#rise of the arthropods#naraoia#naraoiidae#aaveqaspis#liwiidae#nektaspida#artiopoda#euarthropoda#arthropod#panarthropoda#ecdysozoa#protostome#bilateria#eumetazoa#animalia#art#lisa frank aaveqaspis

111 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cambrian Explosion #50: Artiopoda – More Than Just Trilobites

The dominant group of Cambrian euarthropods were the artiopodans, a hugely diverse and long-lasting lineage that included the familiar trilobites along with all their close relatives.

They were some of the first euarthropods to appear in the fossil record, with fully formed trilobites seeming to "suddenly" appear about 521 million years ago and quickly spread worldwide. With the ancestral euarthropods estimated to have arisen between 550 and 540 million years ago, and the ancestral artiopodans not long after that, this means there must have been a lot of very rapid evolution and diversification in the space of just 20-30 million years.

Artiopodans were generally seafloor-crawling animals with flattened bodies and wide flaring segments in a trilobite-like shape. Different species could range from about 1mm (0.04") to around 70cm long (2'4") – with the largest Cambrian forms reaching as much as 55cm (1'10"), rivalling some of the bigger radiodonts in size.

Their exact position within the euarthropod family tree is still uncertain and varies from analysis to analysis, sometimes allied with the chelicerates in a group known as arachnomorphs, or sometimes instead placed as stem-mandibulates. Also sometimes the marrellomorphs are considered to be closely related to them.

———

Sidneyia inexpectans was an artiopodan from the Canadian Burgess Shale deposits (~508 million years ago). Up to about 12cm long (5"), it had a somewhat boxy shape with three clearly defined body regions – a head shield with small stalked eyes protruding from the sides, a segmented thorax, and a tail with a fluke-like tail fan.

It was probably a bottom-dwelling predator and scavenger, and preserved gut contents show it mainly fed on hard-shelled prey like small trilobites.

It seems to have had a fairly widespread distribution, with fossils also known from similarly-aged deposits in North China. Possible additional fossils have also been found in Greenland and the United States, and a potential second species Sidneyia sinica in the 10-million-year-older Chengjiang deposits in southwest China, but these aren't widely accepted as being valid.

Living alongside Sidneyia in the Burgess Shale ecosystem was the enigmatic Burgessia bella. About 4cm long (1.6"), it resembled a tiny horseshoe crab with a rounded carapace, a pair of antennae, and a long tail spine. It had no eyes and was probably a seafloor scavenger, feeding on carrion and organic detritus.

Its evolutionary affinities are uncertain, but it's often placed as a close relative of either the marrellomorphs or the artiopodans.

———

The xandarellids were a group of rare artiopodans characterized by unmineralized shells, large semicircular head shields, and "segment decoupling" – having each plate on their backs associated with multiple pairs of legs instead of just one, with the number of legs per plate increasing further towards the rear of their bodies.

They're known mainly from the Chinese Chengjiang fossil deposits (~518 million years ago), but a single species in the younger Moroccan Tatelt Formation (~508 million years ago) indicates they had a wider and longer range than previously thought.

Cindarella eucalla from Chengjiang is one of the better-known members of this group, with both its exoskeleton and some of of its soft-part anatomy preserved in some specimens.

It was a fairly big euarthropod for the time at about 12cm long (5"), and had nearly 40 pairs of legs but only about 23 body plates, some of which were completely covered by its large head shield. Its stalked eyes stuck out from under the sides of its head and had around 2000 lenses each, suggesting it had excellent vision.

It was probably an actively mobile animal living on or near the seafloor, either hunting smaller animals or scavenging, with its keen eyesight allowing it to both locate food in low-light conditions and avoid larger predators like radiodonts.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#cambrian explosion#cambrian explosion 2021#rise of the arthropods#artiopoda#sidneyia#burgessia#cindarella#xandarellida#marrellomorpha#euarthropoda#arthropod#panarthropoda#ecdysozoa#protostome#bilateria#eumetazoa#animalia#art#the prettiest cambrian princess

142 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cambrian Explosion #51: Artiopoda – Surprising Lookalikes

The aglaspidid artiopodans were a major lineage of early Paleozoic euarthropods – one of the most diverse after their cousins the trilobites, although far far behind them in terms of actual species numbers.

But despite their diversity and worldwide range actual fossils of them are incredibly rare, and for a long time they were considered to be a "problematic" wastebasket group of uncertain affinities, mainly interpreted as being related to the chelicerates. More recently evidence from preserved limb anatomy has instead placed them within the artiopodans in a grouping known as vicissicaudatans, closely related to forms like Sidneyia and the later cheloniellids.

Unusually for euarthropods they had a phosphatic exoskeleton, and they experienced their main burst of diversification in the late parts of the Cambrian period, after most of the actual evolutionary explosion had already settled.

They mainly inhabited shallow near-shore environments, and may actually have been some of the very first animals to venture onto land. Some examples of the trace fossil Protichnites might represent aglaspidids scuttling over the Cambrian shorelines to mate and lay their eggs in a similar manner to horseshoe crabs.

———

Kodymirus vagans was first discovered in the 1960s but was an enigmatic species for quite a while. It was interpreted as the earliest known sea scorpion in the mid-1990s, but more recently it's been reclassified as a vicissicaudatan artiopodan that wasn't quite a true aglaspidid, instead being a very closely related "stem" lineage.

Known from the Paseky Shale in Czechia (~514-509 million years ago), it reached about 8cm long (~3") and had a distinctive pair of large spiny appendages that resembled the "great appendages" of stem-euarthropods like megacheirans. However, unlike the disputed anatomical origins of those structures, Kodymirus' huge claws were instead modified from its first pair of legs in a striking case of convergent evolution.

(Some older reconstructions depict it with six pairs of enlarged limbs, but this is based on the outdated sea scorpion interpretation. A more recent study of specimens found individuals were only ever preserved with one pair each.)

It lived in very shallow brackish coastal waters in a calm lagoon, in what seems to have been a rather sparse ecosystem completely lacking many common Cambrian animals like trilobites and brachiopods. Possibly the environment was isolated and inhospitable enough that it allowed Kodymirus to take advantage of an ecological role usually occupied by other arthropods.

Scratch-mark trace fossils in the Paseky Shale match the size and shape of Kodymirus' raptorial appendages, but only ever show one side being used at a time. This suggests it was an active predator that swam along just above the seafloor, trailing the spines of one appendage through the soft surface of the sediment and "skimming" for hidden prey to grab.

———

Glypharthrus trispinicaudatus was part of a lineage of Cambrian aglaspidids that were even more trilobite-shaped than most other artiopodans, convergently evolving a very similar appearance despite not being particularly closely related to them.

Known from the Guole biota in southern China (~490 million years ago), it was about 3cm long (1.2"). It had a large semicircular head shield with elongated eyes, 12 body segments, and a pair of furcae and a long tail spine at the rear of its body.

Like most aglaspidids it inhabited fairly shallow waters, with the Guole fossil assemblage probably representing an upper continental slope.

———

The aglaspidids were successful and hardy enough to survive past the end of the Cambrian and into the Ordovician – although "Ordovician-type" members of the group had a distinct appearance compared to their earlier relatives, with more rounded head shields and their eyes either very reduced or missing entirely, suggesting that they took up a different lifestyle.

They eventually disappeared towards the end of the Ordovician, about 450 million years ago, possibly struggling to cope with increasing competition from the ongoing Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#cambrian explosion#cambrian explosion 2021#rise of the arthropods#kodymirus#glyptharthrus#aglaspidida#artiopoda#euarthropoda#arthropod#panarthropoda#ecdysozoa#protostome#bilateria#eumetazoa#animalia#art#convergent evolution#the cambrian really liked evolving a nice pair of grabby hands huh

105 notes

·

View notes