#as that picture remains the only accurate illustration of my gender

Text

A Guide to the Best Editions and Translations of Some Classic Literature

TWENTY THOUSAND LEAGUES UNDER THE SEA BY JULES VERNE

IMPORTANT: Whatever you do, DO NOT BUY the edition translated by Lewis Mercier. In fact, NEVER buy any translation of ANYTHING by Lewis Mercier. Mercier’s translation is unfortunately the most “standard” and popular translation. This translation is said to have removed about 20-25% of the original novel, and also removes a lot of Verne’s original meaning. In short, it was a botched translation that somehow became very popular and accessible up until the 1970′s, but always still check for before buying. Barnes and Noble still has his translation lying around for sale.

If the name of the translator isn’t on the cover or back cover of the book, you can check the first few pages where they write the publication history. It might be in fine print.

Frankly, any translation that is NOT by Lewis Mercier is good.

The pictures I have attached here are of the edition I bought published by The Franklin Library. It was translated by Mendor T. Brunetti. It also includes the original illustrations, which is cool.

THE HOLY BIBLE

Oof. This one can get really dicey. But I’ll explain it the best I can.

There have been dozens of translations of the Bible, if not hundreds. Not everyone uses the same one, especially evangelical groups like Pentecostals and Jehovah’s Witnesses. These more radical groups have willingly altered the Bible to further their views. So, a Bible that a Jehovah’s Witness holds is not the same Bible that a Roman Catholic priest holds.

The King James Bible (KJV, or King James Version) has often been considered the most popular version of The Bible throughout modern history. Many of the Bible’s most memorable quotes are directly taken from the King James Bible. It’s considered dignified, poetic, and beautiful. It’s also wrong. So very, very wrong. It’s quite possibly the worst translation of the Bible ever made. I grew up in Catholic school and even there we never once touched the King James Bible. The problems with the King James Bible include certain “theological biases” (i.e. implying Jesus appeared somewhere when he didn’t) and all-around bad translations (i.e. it says there were unicorns but the real meaning is supposed to say “horned beasts”) (see ReligionForBreakfast). The other annoying thing about the King James Bible is that quotation marks are not used. This can be very confusing for readers as it becomes unclear who is speaking.

If you’re curious to see how an exact literal translation of the Bible into English goes, check out the Interlinear Bible. It has the original Hebrew and Greek text with the English words underneath (or besides). You will quickly realize just how complicated translating the Bible is, as Hebrew does not have many words. The English prose in the Interlinear Bible therefore can read like gibberish.

If you want to read the Bible with as close to the original intent and meaning as possible while also being readable, then go for the New American Standard Bible. It can still be a bit difficult to read though. The current popular edition is the New Revised Standard Version. This newer edition from 1989 is considered the most neutral of all translations, as it does not hold any denominational bias. The translators even placed gender-neutral words, such as “people” instead of “mankind”.

FRANKENSTEIN BY MARY SHELLEY

The original 1818 text by Mary Shelley has been given more spotlight as of late. The text that we are most commonly familiar with from 1831 had the story toned down because of course it would be scandalous for a woman to write about such things at the time. Mary Shelley had suffered critical outrage and pressure for editorial changes from her husband Percy for her original vision. For the 1831 edition, she was forced to edit the novel so that Dr. Frankenstein would be a more moral character, whereas the original Dr. Frankenstein in the 1818 text did not go through much moralizing.

Penguin Books recently released an affordable edition of the 1818 text.

THE THREE MUSKETEERS BY ALEXANDRE DUMAS

There are numerous translations but I want to highlight the one I read by Richard Pevear. This made the story very readable while also remaining faithful to the story. Pevear didn’t censor Dumas’s original meanings at all like previous translations did for their time. I thoroughly enjoyed his translation and was lucky enough to get the hardcover of his first edition back in the day. My mom completely surprised me by buying that book for me, and it ended up happening to be the best translation. The best thing about Pevear’s edition is that it includes footnotes for archaic terms. The original hardcover of Pevear’s edition is difficult to find by now, but his translation has been re-released by other publishers. As of a few years ago, a new translation by Lawrence Ellsworth has been released. I have not read that one but have heard good things. The publishers of the Ellsworth translation have also been republishing ALL of the Musketeer stories to provide a series of consistent editions, which has always been rare for the Musketeer saga.

HOMER’S ODYSSEY, ILIAD, and VIRGIL’S AENEID

First off, read these epics in verse form. I cannot believe there are editions out that written in prose form. I’m sorry but that should be illegal. I grew up reading Robert Fagles’ translation, which is pretty damn good and is the standard in schools. However, also look for Richmond Lattimore’s translation. Lattimore translated The Odyssey and The Iliad in the original rhythm that Homer intended. Fagles wrote in freeform for the sake of being easier to read. Both translations retain the original meaning, so it’s up to you really what you prefer. As for The Aeneid (Lattimore only translated Greek classics), go with Fagles.

DON QUIXOTE BY MIGUEL DE CERVANTES

Read the translation by Edith Grossman. That’s all I can say. I devoured that book in days. Grossman did to Don Quixote what Pevear did to The Three Musketeers. It’s just that good and readable.

Ormsby is the second-best, being the most scholarly of all translations. The translation is the most accurate but the humor can be dry and doesn’t pack the same punch as Cervantes probably intended.

The translations to avoid like the plague are by Motteux, Smollett, and John Phillips.

SHERLOCK HOLMES BY SIR ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE

Surely, most people reading this have a copy of the Sherlock Holmes tales in one form or another. But which is the best?

Every text out there is the same no matter the publication, but I prefer to read the way it was originally formatted with all the illustrations. The automatic assumption people might have is that all the original Sherlock Holmes stories were published in The Strand Magazine. This wasn’t the case. There were several stories published in other magazines at the time, such as A Study in Scarlet and The Sign of Four, to name a few. Therefore, if you find an edition boasting to have “all The Strand illustrations” it probably only has the stories that were published in The Strand Magazine. More confusing yet, some editions do say “All the Strand illustrations” but also include A Study in Scarlet and The Sign of Four.

Keep in mind this magical number: 60

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle wrote a total of 56 short stories and 4 novels with Sherlock Holmes. If the copy you are holding does not add up to 60 stories, don’t bother. You might get a copy that comes in two or three volumes.

#onreading#literature#translations#language#languages#mary shelley#bible#Christianity#catholicism#religion#don quixote#jules verne#twenty thousand leagues under the sea#alexandre dumas#frankenstein#the three musketeers#homer#odyssey#iliad#virgil#homer's odyssey#homer's iliad#books#book#classics#classic#classic literature#sherlock holmes#sir arthur conan doyle#reading

38 notes

·

View notes

Text

Queering KH: Part 2

How to Queer this Anime Game? By me, an American nerd lol

Pictured: Dream. Drop. Distance. Sequel. 8)))

What is Queering

I’m so excited to talk about this okay this is literally the only fun thing I get to do as an English major anymore lmao.

“Queering a text” is the academic term for taking a given text and extracting the queer subtext of it, or applying a queer reading to it. It is taking a piece of literature, film, or art and reading into it for the gay coding. It is an especially important tool for reading old literature written during periods of extreme homosexual oppression, wherein the author would be forced to hide hints of homosexuality under layers and layers of superficial text.

Pictured: Sora and Riku battling Ursula as she means to wreck their ship, mirroring the disaster that Sora’s friends Eric and Ariel (lovers) faced at sea.

As a post-structuralist, I am also here to inform you that every text is made up of intertextual influence. This means whether the JK Rowlings of the world intended it or not, their characters may well be queer coded because of the unconscious influence of homoerotic customs in our culture that have permeated the text. It’s why people speculated that Newt Scamander was gay, because he showed little interest in Tina and preferred to focus on his beasts, which is not normative for a male protagonist in straight media. People likewise considered that Merida from Pixar’s Brave might be gay, because she had no interest in dating men and wanted to live a wild lifestyle traditionally associated with masuculinity, things that are pretty in line with lesbian coding. And let me tell you, lgbt claimed Queen Elsa IMMEDIATELY for very good reason. Pretty much everything about her journey, purposefully or not, makes for an strikingly overt gay metaphor. Let it Go is a coming out song for a woman suffocating under normativity all her life, deal with it.

Same, Elsa.

Oh whoops I accidentally pasted this picture of Riku here.

Keep Cultural Distinctions in Mind

Something else important I want to point out is that different cultures are- different lol. They are going to vary. What is queer coding here is not necessarily queer coding in Japan. A man presenting femininely in American media would certainly get him coded as gay. A bishonen in an anime though? Not so much. Men bathing together in Japan is common practice so that would mean nothing gay over there. In America however, you have things like this vine.

In which 2 dudes are chilling as far away as possible from each other in a hot tub to prove they are not gay lol.

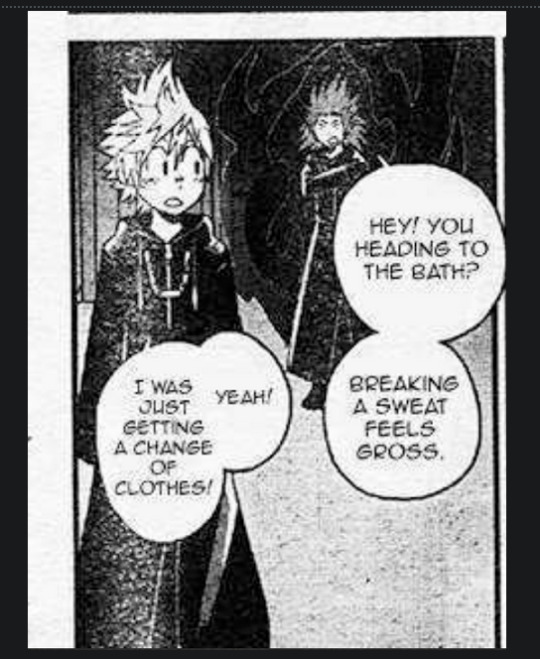

So when I say the male members of Organization XIII bathe together, it means literally nothing in a Japanese context.

But let me tell you this: homosexual mlm tend to enjoy bathing with other dudes. Sexual attraction is sexual attraction no matter where you go. So how would you queer code a Japanese character as gay in a hot tub context?

By American logic, if the straight thing to do is sit 5 feet apart in a hot tub, then the inverse, the gay thing to do, would be 2 men sitting very close together in a hot tub. So if I were to code 2 American male characters as gay in a hot tub context, that is what I would do. But if I really wanted to hammer it home, I would ALSO have them blushing so there is no straight explanation for their closeness.

And for a Japanese character, for whom bathing with men might well mean nothing, I’d definitely have them physically blush, so that you know it does NOT just “mean nothing” to him...

Oh look at that. Amano went out of her way to draw Roxas blushing at the concept of bathing with men. So when I say “the members of Orginization XIII bathe together”, you know that means something to Roxas, cuz the coding tells us so. There are indeed certain ways you can depict a shonen being either interested in or at least affected by that idea. You just have to mind those codes telling you what the character really feels, especially when they can’t really say it.

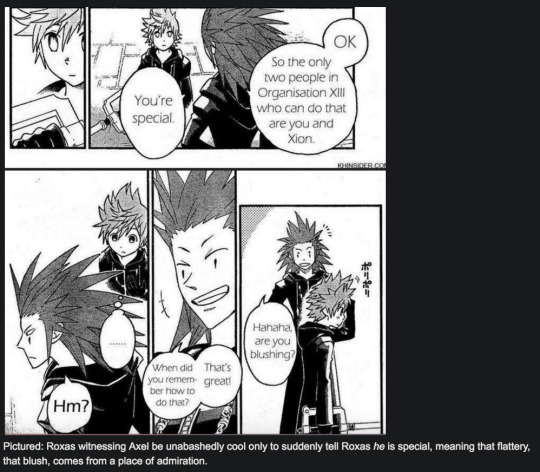

Speaking of blushes, Amano uses them a lot.

They’re a pretty effective tool for hiding gay coding into your characters cuz an anime character might blush for any number of reasons, from being flustered by their crush,

to being flustered because they don’t have a crush.

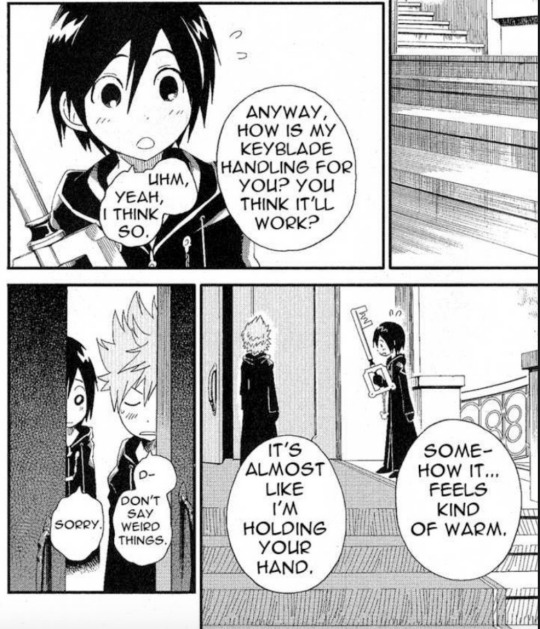

If you’ve ever translated Japanese media, (I haven’t, but I have friends who do), you know that Japanese is very vague which means you need the whole context to properly understand a scene. It’s a similar situation with queer coding. Consider this scene of Roxas blushing.

If Roxas felt positively about the insinuation that he and Xion are holding hands, how might one code this? Well, if he’s feeling really excited about it in a positive way, you might draw him smiling or expressing flattery on his blushing face. However, Roxas reacts negatively, with a frown on his blushing face. This insinuates he does not like this idea at all, especially since he also shuts it down right away in his dialogue.

But you might say “Well how do we know he isn’t just shy?” to which I say- well we can’t know. That’s the whole point of queer coding in literature. It is to say a character is queer but without actually saying it, to give plausible deniability for safety. It is to suggest a character is queer but without any confirmation. It does not mean that the character isn’t queer, however. It just means it cannot be confirmed by the text alone. However, a bold text that is very determined to have hidden queer characters without any straight explanations, will provide coding that has very little or no straight explanation.

Back to the Roxas and Xion dialogue^. This scene alone cannot confirm or deny anything. As I explained however, the suggestion that Roxas is not straight IS there. Considering the whole context, also, this scene is another piece of “evidence” to add to the pile of suggestions that Roxas isn’t straight. This coupled with the bathing panel, and this panel of him admiring Axel, his male mentor, with deep flattery during his first day of adventuring, all exist.

Roxas does not express negative sentiments in his blushing at men, nor does he say anything dismissive to them. When he blushes at Xion’s comment, however, it is with a negative reaction. Consider also that if the author wanted Roxas to appear straight, she would present them in ways that allude to straightness and NOT in ways that allude to queerness. Roxas would not do suggestively queer things like blush in flattery at Axel calling him special and then dismiss Xion’s suggestion that they are holding hands if he were simply coded as straight. Queering a text sometimes requires a lot of critical thought like this. This is because again, these things are hidden, and sometimes hidden really well so that unsuspecting straight people will not even consider the queer suggestions. This is one of the advantages Nomura has in his favor with Kingdom Hearts: by making it so convoluted, the gay text can be forward, strong, and blatant but remain undetected by straight powers. This keeps the series safe from oppressive scrutiny. Characters like Namine and Xion can exist as literal illustrations of compulsory-heterosexuality. And people will still think Sora and Riku are straight.

Even if I don’t know all the queer codes Japanese culture might specifically have, (and I do not, I do not live in Japan nor have any semblance of what that is like beyond what my friends who have lived there can tell me, and what I can research while sitting in my pajamas in Kentucky lol), there are certain things that are rather universal. Blushing, physical contact, lingering gazes, etc etc. Attraction is attraction and certain body language and other physical symbols will translate and will travel. So that’s the majority of what I will have to focus on.

But I do want you to know that rainbows are still gay in Japan.

Finally I also want to express that cultural intermingling is a thing. We do not live in bubbles, especially with the internet. Our cultures affect each other ALL the time. Although Kingdom Hearts is primarily a Japanese series, it is consciously tailored to appeal to both America and Japan. This is by design given the idea was to marry a Japanese hit like Final Fantasy with an American phenomenon like Disney’s media. This is why they take special care in minding the English translations and dubbing of the KH games (when they are able to do so, mistakes are still very often made and i hate it cuz they’re usually heterosexual-agenda-pushing “mistakes” =~=). The games are so intimately tied to both the Japanese and American cultures they are derived from which is part of why accurate translations are so important. And given what they would mean for queer audiences, what they represent for queer people makes accurate translations even MORE important. Some things get quite lost in translation, and some things are grossly added in translation. We will discuss that down the line...

A brief aside that I implore you to ignore:

On the subject of Roxas not being straight, I have heard of one really fun queer motif in Japanese media which is ”ryoutoutsukai (両刀使い)”, “the two sword fencer”: the dual wielding bisexual. Now- I do not necessarily think this is a means of coding Roxas as bisexual, and beyond that, from what I’ve heard in my research on bisexuality in Japan, certain age groups don’t even believe in bisexuality there. However, a love of more than one gender exists no matter who is willing to acknowledge it or not, and this motif is there. And Promisekeeper and Oblivion do rather fit the bill of representing homosexuality (Oblivion/Soriku) and heteronormativity (Promisekeeper/Sora and his childhood friend Kairi). So- while i don’t think it means anything, this fun idea is there~ I will say, however, that as far as I can tell, Nomura and his staff know exactly what they’re doing with their queer coding and are well connected to it in both cultures. So I mean- if any anime team would know bisexuality exists and how to code it, I firmly believe the KH team would, so. There is some food for thought for you~

Get ready for part 3, I hope you like TWEWY~ B)

71 notes

·

View notes

Text

How Digital Marketing Will Change in the 2020s

How many times have we marveled at how a product or service we were discussing with friends or family, or even just thinking about has shown up on our social media feeds, with an option to buy? Equal parts convenient and fascinating, the data gathering and analysis underlying such occurrences is integral to digital marketing.

Targeted marketing

With our digital footprints being ever-increasingly detailed, and media and IT conglomerates making data sharing across platforms seamless, the opportunity to really drill down audiences in the market for various products and services is truly endless. The future here looks like me being able to find exactly that item I have in my head, without an excruciating search process and numerous dead ends.

Personalization really is the name of the game, rendering the mass-marketing techniques of yesteryears obsolete. To take full advantage of this, marketers ought to deploy tools for effective data gathering and analysis, which then inform marketing strategies. After all, it is a telling statistic that 80% of consumers prefer doing business with entities that offer personalized services.

Micro-influencer marketing

Influencer marketing is already making waves across industries, as this avenue encourages niche marketing and sponsorship.The appeal of influencers lies in the authenticity they represent as they show audiences the inner workings of their lives and connect with followers through common interests. This is a platform that will become increasingly important, with 70% of today’s teenagers having more faith in influencers than in celebrities, illustrating the power of influencer endorsements.

The future of digital marketing in this sector will emphasize micro-influencers who have fewer followers but a more targeted reach, translating into better engagement, as these influencers are able to better connect with their followers and generate content that is highly relevant to them.

So how do you make sure you don’t miss the boat on this one? Do your research on the influencers whose platform is most suited for your brand, and establish working relationships with them for one-off or longer-term promotions across their social media channels. The very first step here should be to familiarize yourself with the influencer’s work to determine if it really is a persona you are comfortable being associated with your brand, as they will serve as a spokesperson of sorts for your organization.

Unlike working with contractors and employees, influencers expect somewhat varying levels of autonomy in content creation; this is in the interest of brands as well, as it helps ensure that sponsored content is in tune with the influencer’s online persona, making it an easier sell and not coming off as a marketing gimmick. The fast-changing landscape of social media means that it is vital to stay up to date on the work of the influencer you’re partnering with, not only with regards to your contract but also looking at the entirety of their work. To stay up to date with the latest trends and rising stars on social media, a regular scan of new platforms and influencers gaining momentum in your industry will become even more important, to keep partnerships fresh and to widen your reach through such marketing.

Niche social media channels

As the community of influencers changes rapidly, so do the platforms they use. Alternative channels like TikTok, Snapchat, Pinterest, Medium, and Reddit, are seeing higher usage rates. While Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn and YouTube remain the big fish in this pond, marketers should be paying attention to other platforms as well, considering how they may find their audiences there too. We are also likely to see a continued focus on social media analytics and evaluation, with more sophisticated measurement tools taking the market by storm.

Interactive content

Interactive content is taking over, leaving traditional content behind; a trend we will only see more of. This user ability to manage their experience and personalize the content they’re exposed to will pave the way for the future of digital marketing. Creating fun and engaging interactive components like polls and quizzes for instance, is already important, and will become even more so as brands need to differentiate in an increasingly competitive market.

Here are some ways that interactivity will become front and centre of digital marketing efforts of the 2020s:

Social commerce / Shoppable posts

Currently, more than half of the buyers out there, research their prospective purchase on social media. It should come as no surprise that allowing customers to shop directly through a social media platform, without leaving the app, will become more common and heavily used.

To best utilize this feature now and in the future, companies must focus on creating a smooth end to end purchase experience that is quick, easy to use and enhances the likelihood of a completed sale.

Voice search

The prediction that more than 50% of searches this year will be voice searches (as per ComScore) demonstrates that while this technology has been around for some time, its usage has gone up significantly recently and will continue to do so. As voice-activated devices like Alexa, Siri and Google Voice become more prevalent and accurate, it will become vital to include voice search in digital marketing planning, and to optimize content for voice search. This may necessitate use of long-tail keywords, and long-tail search queries for search engine optimization, to correspond with how people search by speaking i.e. in a conversational tone, rather than how they would type.

Chatbots

With 80% of businesses looking to incorporate chatbots this year, and an estimated annual savings of $ 8 billion from 2022 onwards attributed to chatbots, it makes good business sense for chatbots to become central to digital marketing. Customers also find chatbots easier to use, responsive at all hours, prompt and accurate, making them even more viable.

Visual search

Image search, available on Google and Pinterest is a visual tool that enables users to take pictures of things and places to find out pertinent details about them, such as where to find what’s in the image, and where similar objects may be available. This will drastically change how users search; and digital marketers would do well to ensure content is tailored to be visually searchable, to avail of this huge opportunity.

AI and automation

AI and automation, having taken over many roles already, is set to play a vital role in digital marketing, so it’s advisable to begin incorporating it, if you haven’t already. AI not only offers companies competitive advantage and the opportunity to move into new businesses areas, it can also help reduce costs and meet demands of consumers seeking AI-compatible products and services.

Additionally, AI can support personalized marketing efforts by collecting improved customer data and enhancing how it’s used. One example of this is the way in which AI can inform video creation, by better understanding viewer behaviour. It also facilitates smoother customer experiences through the use of predictive technology that directs marketing more effectively.

Video

A well-thought out video strategy will also become increasingly important, as consumers gravitate towards audio-visual content. The years to come will be an opportune moment to test out different video styles that cater to the various audiences you seek to engage.

Similarly, the popularity of vlogging is on the rise, given the direct, personal and empathetic nature of this channel. In the 2020s, plan for being able to live-stream events and shoot behind the scenes content, strengthening your relationship with customers, solidifying brand image and better engaging audiences in the process.

Neuromarketing

It’s predicted that neuromarketing will soon become a potential digital marketing tool. This is a method of “analysing measurements of a person’s brain activity to determine which types of content are ENGAGING to them” through the use of complex algorithms, neurometrics and biometrics that accurately measure the emotional responses that content generates, and the attention that its garnering. This can have widespread implications for marketers’ ability to create content that is provably engaging to target audiences and to tailor marketing strategies based on the neurological responses of content consumers.

A word of caution

Data collection on such a wide scale as we`re seeing has implications for stereotyping audiences based on race, ethnicity, gender, socio-economic status, religious affiliation, education level and various other markers of identity. Thus, the tools we use to shape digital marketing will have an essential role to play in avoiding typecasting people or reducing them to labels to predict behaviour; instead, these tools must account for the complex, multi-layered ways in which people make market choices. In addition, compliance with consumer privacy and protection regulations must be stringently maintained, to ensure client rights are protected. Such practices have an added advantage in that they build trust with your audiences, enhancing brand loyalty and supporting positive brand association.

Conclusion

Finally, technological advancements abound, there are nevertheless some marketing tools that will remain relevant, such as paid and organic search campaigns and interactive email marketing. While it’s important to have the right tools in your toolkit, an overarching marketing and media strategy will still remain essential. Technology aids the expertise social media professionals bring, but it does not replace it now or in the decade to come; that is to say, what digital marketing tools offer in terms of efficiency and higher productivity is complemented by the communications experts working behind the scenes. So while we may see more automation, this will create capacity for digital marketers to implement more complex and multifaceted communication strategies, rather than making them obsolete.

In conclusion, the challenge for digital marketers of tomorrow will be to effectively balance current and proven marketing tools with the exciting new innovations coming down the pipeline to implement marketing that is of better quality, more engaging, precisely targeted and able to meet and exceed KPIs.

Sources

https://www.sociallyinfused.com/social-media/social-media-tools-you-need-to-try-in-2020/

https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesagencycouncil/2020/02/03/2020-trends-in-digital-marketing/#2fb3799a2f03

https://medium.com/@bizsites/the-future-of-digital-marketing-whats-new-in-2020-6d13010fb37e#:~:text=Chatbots%2C%20while%20kind%20of%20old,statistics%20for%20AI%2Dbased%20technology

0 notes

Text

Is It Time For Us To Take Astrology Seriously?

New Post has been published on https://kidsviral.info/is-it-time-for-us-to-take-astrology-seriously/

Is It Time For Us To Take Astrology Seriously?

In an April marked by angry eclipses portending unexpected change, the ancient, long-debunked practice of astrology and its preeminent ambassador might be weirdly suited for the 21st century.

View this image ›

Illustration by Justine Zwiebel for BuzzFeed

Every Tuesday and Thursday from noon until 7 p.m., Bart Lidofsky pins a small plastic name tag to his shirt (“Bart Lidofsky, Astrologer”) and receives customers at the Quest Bookshop on East 53rd Street in New York City. After I wander up to him and introduce myself — I am there to have my natal chart read — he leads me to a little table in the back of the store and pulls a gauzy green curtain closed behind us. “For privacy,” he says.

Quest specializes in spiritual, esoteric, and New Age literature, but also sells crystals, runes, incense, divination equipment, mala beads, essential oils, candles, pendulums, gemstones, and “altar supplies.” It smells like church in here. You can picture the clientele — people who are comfortable pontificating about auras, people who know how to hang wind chimes. Lidofsky has been performing astrological readings for 20 years, and his bio contains a long string of bona fides: He’s a member of the American Federation for Astrological Networking and the National Center for Geocosmic Research, and frequently delivers lectures for the New York Theosophical Society. Or, as he calls it, “the Lodge.”

After we sit down, Lidofsky asks for the precise date, time, and location of my birth, and spends the next 45 minutes determining, in his words, “how things fit together.”

Before I leave, Lidofsky — who wears a robust white goatee and small wire-frame glasses — hands me his business card. It is pale blue, and features a photograph of Saturn alongside all the pertinent contact information. “Feeling lost in a difficult world?” it wonders in extra-large type. “Help is available.”

View this image ›

Until recently, I thought of astrology, when I thought of it at all, as frivolous and nearly embarrassing — a pseudoscience unworthy of consideration by serious people. I’m sure I felt at least partially implicated via my age and gender: A short screed in an 1852 edition of the New York Times called astrology’s audience “women and girls who are compelled to struggle as a living,” and declared the practice more odious than “the dozen other species of street swindles for which our city is famous.” In the late 1980s, when a former chief of staff published a provocative memoir claiming Nancy Reagan relied on a San Francisco astrologer to, as Time magazine put it, “determine the timing of the President’s every public move,” Ronald Reagan had to publicly insist that “at no time did astrology determine policy.” It was a major humiliation. Even the celebrity astrologer Steven Forrest has acknowledged his field’s dubious image. “I am often embarrassed to say what I do… Astrology has a terrible public relations problem,” he wrote in an essay for Astrology News Service.

But then there was this sense — suddenly, on the street — that astrology had credence. A 2013 New York magazine story claimed that “plenty of New Yorkers wouldn’t buy an apartment or accept a new job without an astral okay.” An occult bookstore opened on a dusty corner of Bushwick and was rhapsodically covered by the Times (its name, Catland, referenced a song by the British experimental band Current 93; its location in Brooklyn indicated a certain kind of culturally conscious clientele). People were talking frankly about their aspects. They knew which planets are in retrograde; they were jittery about eclipses. And it turns out what I’ve been observing anecdotally in New York — among my undergraduate writing students at New York University, in the press, between the otherwise high-functioning attendees of Brooklyn dinner parties — is supportable, at least in part, by statistics. According to a report from the National Science Foundation published earlier this year, “In 2012, slightly more than half of Americans said that astrology was ‘not at all scientific,’ whereas nearly two-thirds gave this response in 2010. The comparable percentage has not been this low since 1983.” While this sort of acceptance isn’t unprecedented, it’s still a curious spike. Astrology is gaining believers, and has been for a while.

In some ways, these numbers jibe with some broader cultural shifts: Whereas an astrological dabbler may have previously glanced at his horoscope in the newspaper while swirling cream into his coffee, there is now a vast and endless expanse of websites featuring complex, customized forecasts, some further broken down into insane and arbitrary-seeming categories (on Astrology.com, for example, you can consult a “Daily Flirt,” “Daily Home and Garden,” “Daily Dog,” or “Daily Lesbian” horoscope, among other variations). There is more access to astrology, just as there is more access to everything: A person can shop around, compare their fortunes, wait to find what they need.

When I speak to a former student, now 22, about the increase — it seems likely it’s at least in part attributable to her and her peers — she describes astrology’s mysteriousness as its most alluring attribute. She reads her horoscope every month, faithfully. Its inherent fallibility, she says, is precisely what makes it fun. For her, astrology is about feeling the strange thrill of indulging something (vaguely) supernatural, but it’s also about getting what she is really after, what we are all really after now: actionable, interactive information. These days, there aren’t many problems Google can’t solve. Except the problem of what happens next.

While folks her age are hardly the first group to feel the draw of the unknown, it also makes sense that a generation that came of age with the whole of human knowledge in its pockets might find the ambiguity of astrology a little welcome sometimes. For people born with the web, information has always been instantly accessible, so astrology’s abstruseness — and, ironically, its promises of clarity regarding the only real unknowable: the future — becomes appealing. This generation’s predicament, as I understand it, has always felt Dickensian: “We have everything before us, we have nothing before us.”

But then I’m reminded, again, that inaccuracy, or, at least, a belief in the fluidity of truth, is at the heart of the present-day zeitgeist: Our news is often hasty and unverified, our photos are filtered and retouched, our songs are pitch-corrected, our unscripted television programs are storyboarded into oblivion, and most everyone shrugs it all off. Astrology might not offer the most accurate or verifiable information, but at least it offers information — arguably the only currency that makes sense in 2014.

In that way, astrology seems perfectly positioned to become the defining dogma of our time.

View this image ›

The earliest extant astrological text is a series of 70 clay tablets known collectively as Enuma Anu Enlil. The originals haven’t been recovered, but copies were found in the library of King Assurbanipal, a seventh-century B.C. Assyrian leader who reigned at Nineveh, in what’s presently northwestern Iraq. (Some of the tablets are now held by the British Museum in London.) The Enuma Anu Enlil contains various omens and interpretations of celestial phenomena, and accurately notes things like the rising and setting of Venus. According to the historian Benson Bobrick, the Assyrians at Nineveh had distinguished planets from fixed stars and figured out how to follow their courses, allowing them to predict eclipses; they also established the lunar month at 29 1/2 days.

By 700 B.C., the Chaldeans — tribes of Semitic migrants who settled in a marshy, southeastern corner of Mesopotamia — had discerned that the planets traveled on a set, narrow path called the ecliptic, and that constellations moved 30 degrees every two hours. In his book The Fated Sky, Bobrick explains how “the twelve [observed] constellations were eventually mapped and formed into a Zodiac round (about the sixth-century B.C.), and the signs in turn (as distinct from the constellations) were established as twelve 30 degree arcs over the course of the next 200 years.” As early as 410 B.C., astrologers had begun making natal charts, noting the exact alignment of the heavens at the moment of a baby’s birth.

Bobrick eventually suggests that astrology is, in fact, “the origin of science itself,” the practice from which “astronomy, calculation of time, mathematics, medicine, botany, mineralogy, and (by way of alchemy) modern chemistry” were eventually derived. “The idea at the heart of astrology is that the pattern of a person’s life — or character, or nature — corresponds to the planetary pattern at the moment of his birth,” Bobrick writes. “Such an idea is as old as the world is old — that all things bear the imprint of the moment they are born.”

It’s at least hard to untangle the development of astrology from the rise of astronomy, and for a long time, the two fields were essentially synonymous; the divide between the supernatural and the natural wasn’t always quite so entrenched. As Bobrick writes, the “occult and mystical yearnings” of Copernicus, Brahe, and Galileo helped to “inspire their scientific work,” and astronomy and astrology remained close bedfellows until almost the end of the 17th century.

Nick Popper, a historian and author who has studied the intersection of science and mysticism, explains the relationship this way: “In Europe before the Enlightenment, for example, most individuals recognized a distinction between the two. Astronomy was the knowledge of the map of the stars and their movements, while astrology was the interpretation of their effects. But knowledge of the movements of the stars was primarily useful for its service to astrology. On its own, astronomy was most valuable as a timepiece.”

For early modern Europeans, astrology was undeniable and ubiquitous, a guiding force in various essential fields, including medicine. “Every noble court worth its salt had an astrologer on consultation,” Popper tells me. “Typically a physician skilled in taking astrological readings. Many brought in numerous people to help interpret significant events. These figures were [frequently] charged with determining propitious dates, anticipating future transformations, and using horoscopes to assess the character of all sorts of figures. This predictive capacity was not deemed a ‘low’ knowledge, as now, but seen as an utterly vital political expertise.”

Johannes Kepler, one of the forefathers of modern astronomy (he determined the laws of planetary motion, which allowed Newton to determine his law of universal gravitation; Kant later called Kepler “the most acute thinker ever born”), wrote in 1603 that “philosophy, and therefore genuine astrology is a testimony of God’s works, and is therefore holy. It is by no means a frivolous thing.” Three years later, in 1606, he declared: “Somehow the images of celestial things are stamped upon the interior of the human being, by some hidden method of absorption … The character of the sky flowed into us at birth.”

View this image ›

“There are so many misconceptions about astrology, it boggles me.” Susan Miller, arguably the most broadly influential astrologer practicing in America right now, is sitting across from me at a white-tablecloth restaurant on New York’s Upper East Side wearing a dark blue sheath dress, black tights, black knee-high boots, and Hitchcock-red lips. “The biggest is that it’s for women. I have 45% male readers. People just assume that it’s all women. It’s not.”

She is petite and precisely assembled, but not in a grim, bloodless, Park Avenue way. There is something openhearted about her, a vulnerability that borders on guilelessness. I find her instantly kind. We will sit here together for over four hours.

Miller founded a website called Astrology Zone on Dec. 14, 1995; the site presently attracts 6.5 million unique readers and 20 million page views each month. She released a new version of her smartphone app (“Susan Miller’s AstrologyZone Daily Horoscope FREE!”) late last year; her old app was downloaded 3 million times. Miller is hip to the way astrology functions online, having embraced the web from the very start of her career. She is active across most social media platforms, and fluent in the quick rhythm of virtual interaction, often acting as a kind of kooky, round-the-clock therapist. Offline, she employs 30 people in one way or another, has written nine books, and is aggressively feted by the fashion industry, a community in which she functions as an omniscient, beloved oracle.

Miller was born in New York, still lives in the city, and doesn’t have a whiff of bohemian mysticism about her. Instead, she presents as intelligent and detail-oriented, with none of the candles-and-crystals whimsy endemic to New Age bookstores. (A minor concession: Her iPhone, which beckons her often, is set to the “Sci-Fi” ringtone.) She appears legitimately compelled to help people, and offers an extravagant amount of free services to her followers. Of course, “free services” can be a potentially devious vehicle for other, less altruistic pursuits — and Miller does sell her books and calendars on her website, and frequently pushes a premier version of her app featuring longer horoscopes — but it is very, very easy to read and follow Astrology Zone without ever making an explicit financial investment in it. (Miller insists she makes “pennies” from the non-pop-up advertisements on the site.) I believe her when she says she considers her readers friends.

It had started to feel like a colossal waste of energy, fretting over whether or not astrology is “real” — whether or not there are accurate indications of our collective or individual futures contained in the cosmos, whether or not those indications can be massaged into utility by trained interpreters — because the fact is, even beyond our present disinterest in objective truth, reasonable people believe in all sorts of unreasonable things. True love, the afterlife, karma, a soul. Even high-level cosmology, the study of the origin and evolution of the universe, hinges in part on tenuous scientific presumptions. When I considered astrology objectively — the notion that celestial movements might affect activity on Earth, and that people born around the same time of year share might certain characteristics based, in part, on a comparable environmental experience in utero — it didn’t seem nearly as dumb as, say, waving one’s hands around a crystal ball. Or calling someone your soulmate.

Still, astrology is often (rightly) equated with charlatanism: hucksters peddling snake oil, burglarizing the naïve. As with any unregulated business, there are practitioners who aren’t properly trained, who haven’t done the work and don’t know the math; they will snatch your $5 and spit back some vague platitude about the stars. It makes sense, then, that astrology is so routinely conflated with fortune-telling, mysticism. “People think it’s predestination. It has nothing to do with predestination,” Miller says, forking the salmon on her chopped salad. She is careful, always, to emphasize free will in her readings — when properly employed, astrology doesn’t dictate or predict our choices, it merely allows us to make better, more informed ones. As the astrologer Evangeline Adams wrote in 1929, “The horoscope does not pronounce sentence … it gives warning.” It’s the same idea — in theory, at least — as a body undergoing genetic testing to unmask certain proclivities or susceptibilities: to find out what it’s capable of, to preemptively protect the places where it is softest, most at risk.

Miller has written extensively about the debilitating, unnamable ailment she suffered as a child (“I had sudden, inexplicable attacks that felt like thick syrup was falling into my knee,” she wrote in her 2001 book, Planets and Possibilities), and over lunch, she tells me she was bedridden for weeks-long stretches, and endured bouts of extraordinary, life-halting pain. She describes the problem as a birth defect, but her doctors were mystified by her condition, and routinely accused her of total hysteria. Around her 14th birthday, Miller’s parents finally found a physician willing to further investigate her case, and she spent 11 months in the hospital that year, undergoing and recovering from various vascular operations.

“The other doctors were like, ‘You’re very clever, aren’t you? You don’t want to go to school, and you’ve hoodwinked all of us,’” she recalls. “And you know, my mother and father were on my side. But they were the only ones. I could feel how a prisoner would feel when unjustly accused. It was the most horrible thing. To be in so much pain and to be screamed at!”

To date, Miller has received more than 40 blood transfusions. Although she no longer endures attacks, if she were injured again in her left leg — in a way that suddenly exposed her veins — she could easily bleed to death. As of 2001, there were only 47 other documented cases of her particular affliction on record.

The pain kept her out of high school, but Miller studied from bed, passed the New York State Regents exams, and graduated at 16. Shortly thereafter, she enrolled in New York University, where she studied business. The whole arc is remarkable: a narrative of redemption. I can’t tell whether I find it incongruous or inevitable that a kid who was constantly told her pain was not real grew up to adopt a profession that gets ridiculed, nearly incessantly, for being its own kind of con. It speaks to Miller’s self-possession that she is charitable, always, to her skeptics.

“No astrologer believes in astrology before she starts studying it,” she says. “What I have a problem with are people who pontificate against astrology who’ve never studied it, never looked at a book, had no contact with it. And they criticize it without opening the lid and looking inside.” She pauses. “But I’m not an evangelist.”

Miller is famously available to her readers, particularly on Twitter. The medium suits her: Her dispatches are sympathetic, personable, chatty. Aggressively educated young women, especially, share them in a half-winking, half-sincere way, indulging in astrology’s prescribed femininity and wielding it in a manner that feels almost confrontational. It reminds me, sometimes, of the way women talk to each other about nail polish: as if it were a political act to not be embarrassed by it.

Miller, for her part, spends loads of time answering questions from her more than 177,000 followers, like, “I need to have oral surgery. when should I schedule? Aries w/Virgo rising.” (“Every Aries I know is having oral surgery,” Miller wrote back. “My daughter had it too. Go ahead and have it — think of it as repair work. Good time!”).

Advice like this would be troubling if Miller was not always exceedingly mindful of her influence (she says she would never tell someone not to have surgery or not to get married on a specific day), and it is, in fact, troubling regardless; her readers take her work seriously. She is pestered with inane questions like some sort of human Magic 8 Ball. If there is any delay in the appearance of an Astrology Zone forecast — they are posted, en masse, on the first of the month — people get agitated. The tweets accumulate, and range in timbre from bummed to slightly desperate: “Waking up the first day of the month to find that Susan won’t post for another 24 hours is the worst,” “It won’t officially be spring until Susan Miller posts her March horoscopes,” “This wait on @astrologyzone is killing me,” “Why is @astrologyzone always late? Every other astrology website posts on time but the best.”

Eventually, the forecasts always appear. Miller stays up very late — until 2 or 3 in the morning, most nights — and wakes up at 7 to exercise, screen several news broadcasts (she likes to compare them, to see how certain stories are prioritized), run errands, and, eventually, around 11 a.m., start writing. She generates at least 40,000 words every month for Astrology Zone, and produces detailed horoscopes for Elle, Neiman Marcus, and a slew of international publications, including Vogue Japan.

Anyone who’s ever interviewed Miller has observed that she’s a circuitous, digressive storyteller, and her monthly forecasts are far longer — they’re essays, really — than a typical newspaper or magazine horoscope, which usually contains just a sentence or two of fuzzy wisdom. Miller can be specific in her advice (“I suggest you do not accept a job now, not unless the offer emanates from a VIP from your past. In that case, you would be simply continuing your relationship, not starting a new relationship, and you therefore would be on safer ground during a Mercury retrograde phase,” she cautioned in February), and she calls her work “practical astrology,” which differs, she said, from “psychological astrology.” She wants to be service-oriented. She wants to give people information they can use.

“I can tell right away if you had a harsh father or a critical mother,” she says. “I might mention it. But I’m not going to delve into your childhood and growing up. I think that’s the work of a psychiatrist.” Instead, Miller finds out how certain astrological phenomena have affected a client in the past, and then, when those events are about to repeat, asks them to recall the state of their life at that prior moment. “When I do a chart the first time, there is so much information there. I have to watch your proclivities.”

Miller pulls out her MacBook and opens a program called Io Sprite. She plugs in my birth information, and a pie chart appears on the screen. It contains several concentric circles; the outermost circle is divided into 12 sections, one for each sign of the zodiac. Individual slices contain glyphs representing the sun, the moon, planets, nodes, trines. It is a snapshot of the sky at the moment of my deliverance, and it is the lynchpin of Western astrology.

Besides the placement of celestial bodies, astrologers also consider what they call “aspects” — the relative angles between planets — and use the natal chart to determine an ascendant or rising sign (the sign and degree that was ascending on the eastern horizon at the time of birth; astrologers think this signifies a person’s “awakening consciousness”). The planet closest to one’s ascendant is that person’s rising planet, and is believed to indicate how we approach or deal with other people. Every astrologer will interpret a natal chart slightly differently. Miller compares this to how various broadcasters report the same news, but emphasize or deemphasize certain narratives. She tells me it is important to find an astrologer that I like and trust.

“You have Uranus rising the same way I do,” Miller says, staring closely at my chart. “Your thought patterns are different from everybody else’s. You think they’re the same because you’re living inside of your body, but they’re different. That influences your personality. People will remember you. And at some point in your life you will form a path for people. You will expose something or teach them something that they didn’t know about.” I’m not sure how or if I’m supposed to respond, so I chew on the end of my pen and look up at her like a puppy dog. I want her to tell me everything. Maybe I don’t believe in astrology, or at least not entirely, but I’m also not immune to the lure of whispered prophecies.

Obviously, the personality attributes commonly associated with most signs (and repeated by astrologers) are positive, and if they’re not immediately complimentary, they’re at least forgivable (“secretive,” “stubborn”). In astrology, no one is “strangely shaped” or “sort of dense.” I am a Capricorn, like Joan of Arc and LeBron James, which means, according to Miller, that I’m rational, reliable, resilient, calm, competitive, trustworthy, determined, cautious, disciplined, and quite persevering. “Your underlings see you as a tower of strength,” she wrote of Capricorns in Planets and Possibilities. “And indeed you are.” Meanwhile, I have Scorpio rising at 19 degrees, which means I have “awesome sexual powers” and a set of “bedroom eyes” that, I’m told, will get me “just about anything I want.” Like many people, I find my astrological profile to be spot-on.

The most noteworthy scientific repudiation of astrology was conducted in the early 1980s by a UC-Berkeley physicist named Shawn Carlson. He tasked 28 astrologers with pairing more than 100 natal charts to psychological profiles generated by the California Personality Inventory, a 480-question true-false test that determines personality type. The idea was to figure out if a trained astrologer could accurately match a natal chart to a personality profile. “Astrology failed to perform at a level better than chance,” Carlson concluded in Nature in 1985. “We are now in a position to argue a surprisingly strong case against natal astrology as practiced by reputable astrologers.”

It is a surprisingly strong case, in that I’m legitimately surprised that the astrologers fared so poorly, and then further surprised by my own surprise. I wonder, for a moment, if astrology has become so omnipresent and accepted in America — nearly everyone, after all, knows their sign, and has since childhood — that we’re all unconsciously performing our attributes now. That we have assumed them. This seems bonkers.

I recall Wittgenstein: “We feel that when all possible scientific questions have been answered, the problems of life remain completely untouched.”

View this image ›

These days, it’s not terribly easy to find a reputable scientist willing to go on the record about astrology. The practice is so heavily disregarded that folks don’t even want to expend the energy required to debunk it. The American Museum of Natural History tells me they do “not have anyone to talk about this.”

I eventually get in touch with Eugene Tracy, a chancellor professor of physics at the College of William and Mary, who studies plasma theory and nonlinear dynamics, and who recently co-authored a new book (Ray Tracing and Beyond: Phase Space Methods in Plasma Wave Theory) for the Cambridge University Press. Plasma theory — that’s heavy. It posits that plasmas and ionized gases play far more central roles in the physics of the universe than previously theorized. It’s also what’s known as a “non-standard cosmology,” meaning it essentially contradicts the Big Bang, and hypothesizes a universe with no beginning or end. I get a little bug-eyed just thinking about it.

Tracy, who has taught high-level graduate courses in physics and undergraduate seminars in things like “Time in Science and Science Fiction,” acknowledges that science and mysticism now sit in total opposition. “The separation between what we would now call science and religion, philosophy and art, is a very modern development,” Tracy says. “The [early] motivation for studying things in the sky was the belief that either these things were gods, or they were the places where the gods lived,” he says.

Tracy and I talk for a while about Kepler, the last great astronomer who maintained faith in astrology; I am interested in how Kepler juggled his confidences. “He believed that astrology wasn’t working, that it demonstrably wasn’t very predictive. But he believed that it was because they were doing it wrong, not because the field itself was misguided,” Tracy says. “He had that scientific attitude: I need good data to build my models on. But his motivation was mystical.”

I finally tell Tracy that what I really want is a succinct debunking of the entire enterprise: I want to know, definitively, that it can’t work, that it doesn’t make sense. He is gentle in his reply. “Newton’s theory of gravity says that everything in the universe gravitates toward everything else. So that means there is a force exerted upon you by the other planets, by the sun, and so forth,” he says. “Now if you ask, ‘Well, the person who is sitting next to me in the room also exerts gravitational influence on me. How close do they have to be to exert the same gravitational influence as Jupiter?’ I’d say depending on where the doctor stood in the room next to you when you were born, [he] exerted the same gravitational influence [as Jupiter]. So gravity isn’t gonna get you astrology. The argument is that there’s something else going on. And that’s where you get outside the realm of science.”

In the beginning — my beginning, your beginning — gravity was everywhere, and the planets were just planets.

When I ask him why he thought people continued to believe in astrology — to cling to a myth — he likens it to our ongoing interest in science fiction of all stripes. “We don’t want to think of the planets as being empty, that there aren’t stories out there. Just like here,” he answers. “We want to fill the world with stories.”

View this image ›

I have plans to meet my friend Michael in the West Village on a particularly frigid Friday night. Over email, I convince him we should go see an astrologer or clairvoyant of some sort — you know, just dip into one of those tapestried storefronts on Bleecker Street, slip some cash to a woman in a low-cut top. I anticipate resistance, so I tell him we can get a drink first. We meet at a quasi-dive called The Four-Faced Liar, and have 300 beers. I want to see for myself whether astrology — even when practiced in the most pedestrian, mercenary way — can distinguish itself from all your basic soothsaying rackets.

Sufficiently over-served, Michael and I stumble around the neighborhood. (It doesn’t even seem that cold out anymore!) (It is 11 degrees.) Walk-in astrologers in major cities tend to keep bar hours — they are often open until midnight or 1 a.m., at least in New York — and I suspect a decent chunk of their business is derived from rambunctious tavern patrons on the move and in search of one last thrill.

Street psychics obviously command a different clientele than high-end private astrologers (comprehensive natal readings tend to cost between $150 and $200, whereas most people can only stomach shelling out 10 or 20 bucks on a late-night whim), but the questions are often the same; all of our questions are always the same. Speaking on the telephone one afternoon, Miller tells me that people come to her for many kinds of personal advice: love, sex, marriage, friendship, health concerns, career counseling. “This is the most educated generation in history, and they’re reading me because they can’t get a job,” she says. “But they don’t read me just for solving problems. They read me to get a perspective on their life. That’s another misconception,” she sighs. “There is nothing but misconceptions.”

The promise of “perspective” is an interesting way to think about the basic appeal of astrology. It allows us to step back — way back — and get a broad-view portrait of our lives, to have someone say: “This is who you are.” A person could spend her entire life trying to figure that out (which is to say nothing of the subsequent quest — in the unlikely event of a successful self-definition — to have that identity validated). I wonder if part of astrology’s attractiveness doesn’t have to do with its rote assignment of signifiers. All the clues to how a person should be: rational, reliable, resilient, calm, competitive, trustworthy, determined, cautious, disciplined. It feels like a road map, in a way.

Of course, what people really want to know is the future. It’s supremely annoying, not knowing what’s going to happen to you.

Michael and I procure dollar slices on Sixth Avenue and wander over to Houston Street. We find a storefront with a neon PSYCHIC sign. The establishment is called Predictions, and is operated by a tiny Egyptian woman named Nicole, who immediately beckons us inside. Her card says “Horoscopes,” and I inquire about an astrological reading. She is dismissive of the idea. “They read your sign,” she says. “I tell your future.”

The best part of my 10-minute session with Nicole is when she asks Michael to leave, commands me to squeeze a clear quartz crystal in my left hand, and then announces, in succession, that my sex chakras are blocked, that someone bothered my mother while she was pregnant with me, that things other people find difficult I find easy, that I am destined to be with someone whose name begins with “J,” and that I am slightly psychic myself.

Back on the street, I find Michael deep in conversation with two young, dark-haired women who are both contemplating a consultation with Nicole. They say they are going to buy a scratch-off lottery ticket first, and that if they win, they’ll go in to see her. They do not win. I tell Michael how I am supposed to be with Jeorge Clooney.

We turn onto MacDougal and walk past a building with the zodiac painted on the window. The door is locked, but eventually an old woman — toothless, and wearing a pink bathrobe — appears and unlocks it. Despite the iconography decorating her building, she also denies us an astrological reading. “It’s too complicated,” she sighs. “You have to know what you’re doing.” Instead, she reads Michael’s tarot cards while I sit on a chair with a ripped cushion. The television remains on the entire time. “I don’t look at the past,” she says while he shuffles the cards. “That’s for you to deal with.” She proceeds to tell Michael a few things about his future — two to three kids! — but I’m not listening because I’m thinking really hard about nachos. Before we leave, he asks her if she has any ideas for a cool nickname. We discussed this question ahead of time, back at the bar. “Something with a T,” she says. “And an L.” He decides on “Talon” after a brief dalliance with “Toil.” The next morning, I text him the word “TOILET” repeatedly.

If there is a way to ascertain usable info about the future, I am not sure this is it.

View this image ›

The question of why astrology has endured — why, of all the outlier theosophies and esoteric theories, astrology is the one that’s remained in the public consciousness for thousands of years, the one with a presence in nearly every daily newspaper in America, the one that’s flourishing online — might just be attributable to the endless romance of the night sky. Find a field out in the country, wait until dark, look up: It is a fast and easy way to find yourself cowed. There is something seductive about the stars, about their beauty and their strangeness, about what they imply regarding the smallness of our existence here on Earth. In his book The Fourth Dimension, the mathematician Rudy Rucker wrote: “What entity, short of God, could be nobler or worthier of [our] attention than the cosmos itself?”

Eugene Tracy suggests something similar during our conversation. “I think for most of human history, the sky has been very important to people,” he says. “And now we live our lives without it. We’re surrounded by artificial light.”

Astrology is, in the end, a kind of mass apophenia: the seeing of patterns or connections in random data. Although it resembles a pantheism and sometimes gets slotted as such, astrology has never struck me as a useful stand-in for organized religion — it doesn’t proffer absolution or any promise of an afterlife, nor is it a practicable ethos — and many astrologers (including Susan Miller, who is a devout Catholic) nurture active spiritual lives that have nothing to do with the zodiac. Astrology, unlike religion, is a deeply personalized, nearly solipsistic practice.

When I ask Dr. Janet Bernstein, a psychiatrist who’s worked in all kinds of contexts (privately, in prisons, in hospitals, in New York, in Alaska), if she has a sense of why so many different types of people turn to astrology, she points out that it often only takes one win — one “right” horoscope — to convert a skeptic. “Humans seem to like certainty and predictability in many, but not all, situations,” she says. “Astrology is just one of many systems that promises some certainty and predictability. Medical research is another. Stock market analysis is yet another. What often happens when one prediction in a system is born out is that the entire system [is] accepted.”

Back at the Quest Bookshop, when I ask Lidofsky if his belief in astrology requires at least a temporary suspension of cynicism — a “there are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamt of in your philosophy”-type of open-mindedness toward wildly unquantifiable truths — he only shrugs. “I don’t see any logical reason why it works,” he replies. “It just does. Aspirin was the most prescribed drug in the world, and no one knew how it worked until the ‘70s.”

Ultimately, I understand astrology’s utility as a (faulty) predictive tool, even if most astrologers prefer that it not be used that way. I also understand its attractiveness as something to believe in: Here is an ancient art — rooted in the cosmos, the default home for everything divine and miraculous — that promises not only clarity regarding the future, but also a summation of the past. Humans have always been drawn to succinct markers of identity, to anything that tells us who we are.

There is also the assurance of change in astrology: The planets keep moving. The chart always shifts. The forecast refreshes on the first of the month.

One particular story has stuck with me: In July 1609, Galileo discovered that Dutch eyeglass makers had developed a simple telescope, and weeks later, he’d designed and forged his own (improved) version, which allowed him to define the Milky Way as a galaxy of clustered stars, to see that Jupiter had four large orbiting moons, and to reaffirm Copernicus’ heliocentric understanding of the universe. Still, several prominent philosophers, including Cesare Cremonini and Giulio Libri, refused to look through the telescope. Maybe they just didn’t want to see what he saw — didn’t want to challenge one worldview with another. In 1610, in a letter to Kepler, Galileo opined what he called “the extraordinary stupidity of the multitude,” but it’s impossible to say precisely what kept the philosophers away.

I like to think they chose to uphold a private sense of heaven. One that told them exactly what they needed to know.

1.

Sign up for our BuzzReads email, and you’ll get our best feature stories every Sunday — plus other great stories from around the web!

buzzfeed.com

Read more: http://www.buzzfeed.com/amandapetrusich/is-it-time-for-us-to-take-astrology-seriously

0 notes