#because he's used to thinking that any affection directed at him is meant for harvey

Photo

emotional support billionaire

#i was gonna в like 'remember when i talked about two face's self hatred'#but i've never talked about it publically#so anyway#this is around the time harvey is still receiving therapy but is under a house arrest#so he stays at the manor#and#bbh is not dealing with the identity reveal well#because he's used to thinking that any affection directed at him is meant for harvey#since he's been regarded as 'the problem' for years#does shit to your self esteem#so yeah bruce ends up having lot of tough conversations with harv and gives him a lot of smooches#i dunno#a li'l sad#but mostly good#im tired#bruharv#bruharvey#twobats#twobat#two face#batman#harvey dent#bruce wayne#Mik draws

800 notes

·

View notes

Text

Behind The Album: OK Computer

The third studio album from Radiohead was released in May 1997 by Parlophone Records. This would mark the first album that Nigel Godrich worked on as their producer. The band would self produce the entire album themselves, which they have done on every record since. In 1995, Brian Eno asked the band to contribute a song to a charity compilation for War Child entitled Help. They were scheduled to do the recording in only a day, which led to the track, “Lucky.” Godrich would say of the recording. “Those things are the most inspiring, when you do stuff really fast and there's nothing to lose. We left feeling fairly euphoric. So after establishing a bit of a rapport work-wise, I was sort of hoping I would be involved with the next album." This track would form the foundation of what would become OK Computer. In early 1996, the group took a break from touring because they found it a bit too stressful. Thoughts now turned to a new record with the mindset of distancing themselves from anything similar to The Bends. Drummer Phillip Selway would say, “There was an awful lot of soul-searching [on The Bends]. To do that again on another album would be excruciatingly boring.” The label gave the band a rather good sized budget for recording equipment for the new release. A number of producers were considered for the album, but they kept coming back to Godrich as an advisor on equipment. Eventually, the band hired him as the producer. Ed O’Brien said of the album, “Everyone said, 'You'll sell six or seven million if you bring out The Bends Pt 2,' and we're like, 'We'll kick against that and do the opposite'."

In early 1996, Radiohead began proper recording of the LP at Canned Applause Studios in Oxfordshire, England. Issues immediately came up as the band had difficulty staying focused on one song all the way to completion. Selway would talk about this later, “We're jumping from song to song, and when we started to run out of ideas, we'd move on to a new song ... The stupid thing was that we were nearly finished when we'd move on, because so much work had gone into them." Although the members of the group were considered equals, the voice of Thom Yorke always represented the loudest one in terms of musical direction. Godrich would talk about his role within the group in an interview. They “need to have another person outside their unit, especially when they're all playing together, to say when the take goes well ... I take up slack when people aren't taking responsibility—the term producing a record means taking responsibility for the record ... It's my job to ensure that they get the ideas across." His permanent role on each Radiohead album would lead to the producer being called the sixth member of Radiohead. After only recording four songs, the band left the Canned Applause Studio for a variety of reasons Including the fact that the studio had no bathrooms or dining rooms. They decided to take a break from recording in order to support Alanis Morissette on tour, which gave them a chance to try some of their new tracks live. Around the same time, Director Baz Luhrmann asked the band to contribute a song to his film, Romeo and Juliet. “Exit Music for a Film” would be played as the credits rolled during the movie, but they did not give Luhrmann permission to place the track on the movie soundtrack. Yorke would later observe that this song became very important to the album. It “was the first performance we'd ever recorded where every note of it made my head spin—something I was proud of, something I could turn up really, really loud and not wince at any moment."

In September 1996, the band began recording again at a mansion in Bath, England owned by actress Jane Seymour. Jonny Greenwood would say the environment represented a much more pleasant change for the group. It “was less like a laboratory experiment, which is what being in a studio is usually like, and more about a group of people making their first record together." One quality that the band enjoyed during the sessions came in the fact that they took full advantage of the natural environment of the mansion. “Exit Music for a Film” utilized some natural reverb courtesy of a stone stairwell. They recorded Let Down” in an empty ballroom at 3 o’clock in the morning. The group worked at its own pace as Ed O’Brien observed later. “The biggest pressure was actually completing [the recording]. We weren't given any deadlines and we had complete freedom to do what we wanted. We were delaying it because we were a bit frightened of actually finishing stuff." A majority of the album would be recorded live with no overdubs because Yorke hated them. The band completed the rest of the album at the studio in Saint Catherine’s towards the end of 1996. In January 1997, the strings for the album were recorded, then they spent the next two months mastering and mixing the album. Actually, the mixing of the album only took a couple of days. Nigel Godrich would later comment, “I feel like I get too into it. I start fiddling with things and I fuck it up ... I generally take about half a day to do a mix. If it's any longer than that, you lose it. The hardest thing is trying to stay fresh, to stay objective."

Several artists would influence what would become the finished product of OK Computer. First and foremost came the 1970 album Bitches Brew by jazz great, Miles Davis. Thom Yorke would tell Q what he saw in that recording that made up his vision for this album. “It was building something up and watching it fall apart, that's the beauty of it. It was at the core of what we were trying to do with OK Computer." Other artists that helped to inspire the record included Elvis Costello, REM, PJ Harvey, the Beatles, Can, and composer Ennio Morricone. Jonny Greenwood would describe OK Computer as an attempt to recreate the sound on all these great records, but they missed the mark. The band would expand their instrumentation for this album to include electric piano, Mellotron, cello and other strings, glockenspiel and electronic effects. Spin would say this about the release, “A DIY electronica album made with guitars." The lyrics to the album focused on themes much more conceptual when contrasted with The Bends. Yorke would sing about a wide variety of topics including transportation, technology, insanity, death, globalism, capitalism, and more. The singer would say, “On this album, the outside world became all there was ... I'm just taking Polaroids of things around me moving too fast." He also took inspiration for some of the lyrics from a selection of books including Noam Chomsky, Eric Hobsbawm's The Age of Extremes, Will Hutton's The State We're In, Jonathan Coe's What a Carve Up! and Philip K. Dick's VALIS. Despite the abstract nature of the lyrics on the record, many critics have looked upon OK Computer as a concept album. They argue that there exists a singular theme running throughout the record, but the band has consistently denied any attempt at making such a release. Jonny Greenwood commented, “I think one album title and one computer voice do not make a concept album. That's a bit of a red herring." They did pay particularly close attention to the order of the tracklist taking almost two weeks to complete it.

The album opens with “Airbag,” which highlights the drumming of Phillip Selway. The track had been inspired by the work of DJ Shadow. The band would later admit that they represented novices in this attempt to base a song on DJ Shadow due to their lack of time with programming. Yorke had actually read an article in a magazine entitled “An Airbag Saved My Life.” Another book that helped to create the basis for the song lyrics emerged in the Tibetan Book of the Dead. Yorke had always been obsessed with the idea that any time you get into a car you could possibly die at any second. The second track “Paranoid Android” stands out as one of the longest tracks in the band's entire catalog. Two songs inspired it from classic rock, “Happiness Is a Warm Gun” by the Beatles and “Bohemian Rhapsody” by Queen. The lyrics are meant to reference the alien from Douglas Adams’s A Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy. Yorke got the idea after watching a woman lose her mind after a drink spilled on her at a bar in Los Angeles. “Subterranean Homesick Alien” referenced “Subterranean Homesick Blues” by Bob Dylan. The lyrics are meant to refer a person who is abducted by aliens, then returns home to realize his life is in no way any different. The beginnings of the theme for this track actually began for the singer in private school when he had an assignment to recreate a British literary movement called Martian poetry. Romeo and Juliet by William Shakespeare inspired the lyrics to “Exit Music for a Film.” This should come as no surprise as the band had specifically created the song for a remake film. Yorke would use it as a chance to simply recap the entire narrative in the song because Zeffirelli’s version of the film greatly affected him at the age of 13. “I cried my eyes out, because I couldn't understand why, the morning after they shagged, they didn't just run away. It's a song for two people who should run away before all the bad stuff starts.” The singer had tried to replicate Johnny Cash’s Live at Folsom Prison as he sang along to his acoustic guitar. “Let Down” represented an attempt by the band to recreate the sound made famous by Phil Spector and his wall of sound. Yorke would later comment that the lyrics are “about that feeling that you get when you're in transit but you're not in control of it—you just go past thousands of places and thousands of people and you're completely removed from it.” The singer would look upon such lyrics as perfect symbolism for Generation X, which had strongly influenced the direction of it. “Karma Police” contains two major sections that alternate between piano and guitar, which originally came from “Sexy Sadie” by the Beatles. The title of the song was an inside joke between the band during the previous tour. If something bad happened to someone, they would say that the karma police were going to get them. The short Interlude “Fitter, Happier” became something that the Radiohead frontman wrote in 10 minutes while on a break. The voice came from the Macintosh Simpletext software application. He would later describe the words as a “checklist for slogans from the 1990s.”

“Electioneering” turned out to be one of the band’s heaviest rock oriented songs probably ever with lyrics that were inspired by the Poll Tax Riots. Another source of inspiration came in the book Manufacturing Consent by Noah Chomsky. “Climbing Up the Walls” has been described by Melody Maker as “monumental chaos.” The track was arranged by Johnny Greenwood for 16 instruments based on composer Krzysztof Penderecki's “Threnody to the Victims of Hiroshima.” No Surprises” would be initially inspired by “Wouldn’t It Be Nice” by the Beach Boys, but they really wanted to replicate the mood of “What a Wonderful World” by Louis Armstrong or the soul music of Marvin Gaye. Yorke would say the song’s narrator is “someone who's trying hard to keep it together but can't.” The track that started it all “Lucky” was actually inspired by the Bosnian War. Yorke wanted to illustrate the actual terror of that conflict on the charity album, Help. Another theme that he drew upon emerged in his own anxiety about transportation. Critics have likened the guitar on the song to 1970’s Pink Floyd. The final track on the album “The Tourist” was specifically arranged by Jonny Greenwood to create a bit of space on the LP. The lyrics originated from Yorke witnessing tourists in France trying to see as many sites as possible. The title of the album came from the 1978 radio series based on The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy when character Zaphod Beeblebrox says, “Okay, computer, I want full manual control now." They had first heard the line while listening to the series on the bus for their tour in 1996. Yorke would say this about the title later. It “refers to embracing the future, it refers to being terrified of the future, of our future, of everyone else's. It's to do with standing in a room where all these appliances are going off and all these machines and computers and so on ... and the sound it makes." The artwork would be created by both Yorke and Stanley Donwood using a computer. The Radiohead singer would observe this about the art, “It's quite sad, and quite funny as well. All the artwork and so on ... It was all the things that I hadn't said in the songs."

Leading up to the release of the album, the band got very little support from Capitol Records because they did not have too much faith in the commercial potential of it. Much of the pessimism came in the fact that the record did not have any singles to put on the radio. Ed O’Brien would call it the “lack of a Van Halen factor.” The singles that were released from OK Computer included “Paranoid Android,” “Karma Police,” and “Lucky.” All of the singles charted in the top 10 in the UK, while they also did very well making the top 20 on the US charts. Their official website was created in order to promote the record, as well as some non-traditional promotional techniques by the record label. One such idea came in their decision to take out full-page ads in popular British newspapers and magazines with only the lyrics to “Fitter, Happier.” Another promotion sent out floppy disks to people in the press, which included many Radiohead screensavers. Upon its official release, OK Computer would debut at number one on the UK charts, while in the US the record made it to number 21. Please note that this was the highest American debut for the band. By September 2000, the release had sold 4.5 million copies worldwide.

Critics loved the album across the board. Writer Tim Footman would comment, “Not since 1967, with the release of Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band, had so many major critics agreed immediately, not only on an album's merits, but on its long-term significance, and its ability to encapsulate a particular point in history." Many critics saw it as a very important album. Mojo wrote in their review, “Others may end up selling more, but in 20 years' time I'm betting OK Computer will be seen as the key record of 1997, the one to take rock forward instead of artfully revamping images and song-structures from an earlier era.” The New Yorker would congratulate the band on taking many more risks artistically then their contemporaries like Oasis. “Throughout the album, contrasts of mood and style are extreme ... This band has pulled off one of the great art-pop balancing acts in the history of rock." Most of the reviews that were slightly mixed seemed to focus on the fact that when compared with The Bends, this record did not contain as many catchy songs. The release would go on to win the Grammy for Best Alternative Album, but did not win Album of the Year. The praise for the album seemed to inundate the band a little too much. Also, Radiohead did not agree with the universal assessment that they had made the greatest progressive or art rock record since Dark Side of the Moon. Thom Yorke would say, “We write pop songs ... there was no intention of it being 'art'. It's a reflection of all the disparate things we were listening to when we recorded it."

The legacy of the album came to be represented in a variety of ways. First, the release of OK Computer coincided with the election of Tony Blair. Some writers have pointed to the pessimism on the record as a sign of things to come. Stephen Hayden would write, “Radiohead appeared to be ahead of the curve, forecasting the paranoia, media-driven insanity, and omnipresent sense of impending doom that's subsequently come to characterise everyday life in the 21st century." Second, the arrival of this album directly coincided with the decline of Britpop. The Oasis album Be Here Now did not attain the commercial or critical success that What’s the Story Morning Glory had received in 1995. Third, OK Computer directly influenced a new generation of artists including bands like Bloc Party and TV on the Radio. The album has landed on many lists over the subsequent years as one of the best releases of the decade and all time. Yet, not all retrospective reviews have been kind to OK Computer as it has also landed on some lists as one of the most overrated records of all time. A New Musical Express column criticized the release as the exact point when Radiohead stopped being good, but instead started to become important.

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi there!!! It is the same anon that requested some fic recs ☺ Thank you so much! I may give them a read! They look very interesting! But tbh I'm looking for fics that deal with some more in-depth approach to the twins' psychology and character (I don't mind the romance. In fact, I think it's a really interesting plus to the story when handled well).

(Below this is the rest of the messages, put together. Farther down, below the line, are my responses)

I’ve usually seen that the twins are portrayed as soft, loving and caring guys with their partners without real motives for such drastic change of dynamics in their twisted personalities. I mean, the usual Valeska centered fic goes like this: they meet the OC in Arkham or during their childhood in the circus and for some reason they reunite in the present, and then it is just the twins somehow falling for them, changing their whole way of being and only wanting to bang the OC the whole time (without taking into account the lack of the OC's inner conflict about loving such twisted men, because these OCs usually are "sane" and good people that somehow are dragged into the twins' world and for some reason they just fall in love with them without questioning it).

But for me the least realistic thing about these fics is that the twins become super nice guys all of a sudden. I mean of course there can be character develoment and growth (up to a certain point), but I haven't really found a story that contains such deep explanation. Let's face it, they're still psychos no matter what, even if they have a partner.

In the last season we get a glimpse of how Jeremiah treats Ecco, someone that he used to appreciate and care for deeply, and she still meant little to him. So it doesn't add up to me when the twins are magically turned into these super sweet caring guys while their twisted, evil and manipulative side is completely ignored.

I am not saying they can't love, I am just saying that they surely have their own twisted perception of what love is 🤔 Sorry for my rambling, damn, it took soooooo many comments hahaha!!! OMG, Sorry!😂😂 I had a LOT to say 😂😂😂 But I just find these characters very interesting and I would love to read a story with a more realistic approach to the construction of their personalities (and their twisted way of loving too!). Let me know, please, if you happen to know about some fics/authors 😘 thanks again!

- - - - - - - - -

Hi again, anon! I’m sorry my list of content in the previous ask wasn’t exactly what you were looking/hoping for. As of right now, besides the ones I sent you that may delve a little bit below the surface, I can’t think of a true ‘character study’ type story that I have read so far. But, again, I usually stay in the area of romance so I wouldn’t be surprised if there are such fics out there under a different genre.

I’ll be quite honest, it’s been a very long time since I’ve read any oc/(input character here), including ones with the twins. Normally, I forget they exist until someone brings it up or I stumble across one on Tumblr accidentally. I do agree, the twins suddenly changing for an OC (or anyone) can be a bit unrealistic but from my years of reading and writing, creating stories with such things is a bit of ‘wish fulfillment’ which, to be honest, isn’t a bad thing. Sometimes a reader just needs content that is kind of good-feeling type fic (though not in a sense of how murderous the twins can be but in them getting some kind of positivity in their lives, whether it be through an OC or another character in the universe). When I wrote Oc’s at the beginning, it was either wish fulfillment for me or simply just wanting these characters I adored to finally have some kind of happy ending which they probably did not deserve, at all.

A reason you might not find such content is also because, character studies are hard. Especially if you don’t have a complete picture of the character. With the twins, a lot is just coming up with stuff, imaging their past and how it still affects them, even if, on the upper layer we’re shown, doesn’t portray those scars left behind.

With Oc’s, they can usually be pretty hit or miss. It’s not like you’re taking an already known character with known flaws and putting them in your story. Those characters have a foundation already built. For an Oc, the writer has to literally make someone from the ground up, which is equally as hard without making them seem too whiny, too mary-sue like, or just too problematic. This can leave a lot to be desired which can create something unrealistic as well. That’s why I usually only look for content centered around characters from the show, instead of Oc’s; like with Bruce and the twins because canon-wise there is already something there (depending on how you look at it and write it).

In regard to Ecco: firstly, I think it’s arguable what type of relationship she even has with Jeremiah when we first are introduced to them. We’re shown some concern on his end when she’s clearly been hypnotized but this can be seen as a boss concerned for an employee, an employee who he’s probably had for awhile now and is one of the very rare few who he trusts to an extent. However, we just don’t know much of anything about their relationship or past together. She might have hardly seen him, only contacting him through phone calls and text messages; she may have only brought him supplies through the maze and never was in his inner personal areas. This treatment is all possible given how Jeremiah is quite literally a paranoid mess before the spray, no matter how well put-together he appears. And, if we’re to compare this to his eventual obsession with Bruce Wayne, we can take a guess that Jeremiah and Ecco probably didn’t get very deep with this connection they had. Mainly because with just a few compliments, Jeremiah is invested in Bruce, something we don’t see with Ecco before or after the spray. So we have Bruce enter the picture (someone who has run into his twin on multiple occasions, a fact Jeremiah must know to some extent with his paranoia probably leading him to constantly check newspapers and the news for info on Jerome) and, if you look at things from Jeremiah’s perspective, besides complimenting him, Bruce looks at him and only sees Jeremiah. And this would be baffling to Jeremiah if he knows the affect Jerome has had on Bruce, for him to look at Jeremiah and not see his twin after everything would be just as big a compliment as anything because it’s differentiating him from his twin. Someone who has probably feared being compared to his brother, for people to look at him and only see Jerome (such as what occurs with Jim and Harvey only hours prior). Because of this, when compared to Ecco, we can deduce that either their conversations never went in such a direction, or she hardly had the extended physical contact to ever bring up Jerome or compare or compliment. If so, it’s possible with how Jeremiah is that something similar could have happened with Ecco. And this eventually leads into the spray where his only true attachment is not Ecco but with Bruce, especially, after his initial spray, Jeremiah’s hatred for Jerome is far worse than it had been before, making Bruce’s assessment of Jeremiah simply being himself and not his brother, far more endearing as well. So, in comparison to Bruce, Ecco means absolutely nothing to him, a means to an end.

I’ll admit, reading content where the twins are somehow in a relationship (with an oc or canon character) while still being rather insane, are quite interesting. However, for stuff like that to work in a compelling and ‘actual’ way, characters like that have to be bent because these characters logistically working in that kind of environment may never be realistic anyways. This can be worked around of course, but it takes so much time and effort; even now, as I write my stories for Gotham, I’m still trying to work around how to make these ships work for the twins because they’re stubborn and although they have obsessions they, at their cores are not good people and while they may try, seriously try to better themselves, there will always be slip-ups.

I do agree, they can love but it would always be twisted in some way or another (look no further than Jeremiah with Bruce). They’re also a lot of fun to take apart and analyze or try and come up with a type of background that works with all the hints we’ve been given. Background-wise, the twins are really something a writer can make their own which is an interesting concept.

This turned more so into a long ramble of writing and Ocs and lots of Gotham lol but anyways, I wish I could give you a story to fit your needs. I quite hate when I have an itch for certain fics and I either can’t find them or the number of fics is so daunting that I don’t dare even try. I would recommend just going through them, possibly looking for complete content first, or ones with high hits or kudos (depending on the site you’re searching on) because I don’t have any at the moment I can suggest.

(Honestly the ideas for the twins never stop coming lol, perks of their backgrounds and everything else being so hazy.)

I hope some of this message was at least interesting lol and I do wish you luck in finding good twin content that delves into their character or, maybe you’ll get lucky and someone will publish something like that soon! Either way, I hope you find something 😘

#anon ask#anon#Gotham#I don't even know what this became to be honest#I had wayyyy to much time to just think on this answer all day long since i had no access to my computer#and this is what I got lol#Valeska twins#Jeremiah Valeska#Jerome Valeska#Ecco#Wayleska#character study? A little?#oc's#writing#basically oc writing can be really difficult or not#Jeremiah maybe could've had a deeper relationship with Ecco or maybe she just wasn't his type. Who knows#I do stand by my thoughts on him first meeting with Bruce though cause it just adds another layer to his character that I rather like#Gosh I hope this entire message makes as much sense as my brain thinks it does

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Rampage 2 Monster Ideas Or Possibilities

Because this is something well I wanted to make a joke at first of how Davis would react in the situation I’ve thought of for a sequel to Rampage 2018. But over time I started to think more. Basically more details, and changes to my ideas. Spoilers from the 2018 film just in case.

Including I wanted to make this list of ideal monsters. Because the video games have a huge roster that a franchise can use for the games. Along with I wanted to write my own twist on them. Considering the direction the movie took with George, Ralph, and Lizzie. If your a fan of the games you might like these ideas. But give me your thoughts on these. Especially I intend to some how Ralph and Lizzie back. Because along with George are the main trio of the franchise.

This isn’t all for one movie. But again I’m just giving out ideas. In fact I decided to study and look into stuff. Mostly about wolves because I’ve thought more in depth about Ralph 2.0. Including looked up some stuff on Crocodiles, but mostly looked up stuff about wolves. Along with I looked on the Rampage wiki on some characters. Again give me your thoughts, this is all fan fiction. Especially it seems weird with the Ralph one.

1. Ralph or humorously called Ralph 2.0 by Harvey Russell. A 7 month old Grey Wolf taken in by the Wolf Watch UK. Named Ralph by a woman who works there after she found him as a pup laying next to his dead mother who was killed by poachers. Ever since then, even being a wild animal he’s looked towards the woman as sort of mother after his died.

Actually considered a, “Sweetheart” despite his protective nature of the woman. Especially is rather good at protecting itself when aggressive or threatened. After being affected by the same pathogen some how that affected the other animals. Growing in size, and gaining certain abilities. But compared to the original Ralph in 2018, Ralph 2.0 while aggressive, seems to be less violent than the original. Mostly because of being taken care of by humans, and his relationship with the woman who rescued him. Especially he still retains his memories.

But growing in size and other symptoms have caused him to become scared, confused, and angry. Only listening to the woman who saved him, and eventually Davis as well. He’s in a weird way a giant dog. Yet he will become violent and attack who hurts the woman who nurtured him growing up.

Is able to fly like the original Ralph, and use the needles it grew on it’s back.

Notes: Originally I wanted this new character this woman to be played by Karen Gillian, but decided Emilia Clarke. Especially I want a joke where Harvey calls her the, “Mother Of Wolves”. Including Ralph 2.0 has a relationship to this woman similar to Davis and George. But with the woman even calling Ralph that he’s kind of like her son. Along with this Ralph is supposedly the youngest of the trio.

2. Lizzie or humorously called Lizzie 2.0 by Harvey Russell as well. Including actually named Lizzie by Davis. A 5 year old American Crocodile that resides in the San Diego Wild Life Sanctuary, that Davis saved as well. While she doesn’t mind Davis at all. She would rather be left alone. While the American Crocodile may not be as aggressive as other species, Lizzie can be aggressive if agitated.

Affected by the pathogen that made it’s way to the sanctuary, she gained similar abilities like the original Lizzie. She’s the biggest of the three, able to breathe underwater, and has the tusks and more teeth. Especially in a similar situation as Ralph 2.0, confused, and some what scared, but angry as well.

Yet still even growing bigger, she still retained that loner behavior. Even though she’ll follow Davis because he’s the only one she can trust. Later during the film while still aggressive, realizes that her help is needed offers to help the other two against a bigger threat. Especially it’s to protect Davis from harm or any monsters threating to hurt him. Including can get very violent as well.

Notes: There’s this theme for the movie while it sounds ridiculous. Considering the situations with Ralph 2.0 and Lizzie 2.0, especially Ralph 2.0. Davis tries to convince George even if they are different species, and they may not get along. But Davis tells him that Ralph and Lizzie are not like the other two he faced. Along with the fact they are in the same situation they were in 2018. With Davis asking George to see them as like a younger brother and sister or friends, that they are part of his troop, his family, to protect them like they were one of his own. Over the film George understands and risks his life for the other two. Following this, the other two especially Ralph do the same.

Including have a cute scene of George petting Ralph 2.0 or something.

3: V.E.R.N. considered an abomination. A monster that absorbs radiation. Originally a uncomplete monster that was mixed with bat DNA and other animals before Claire was killed by George. But it was mainly top secret and but kept close to the Rampage project. Yet it was stolen by some sort of company who’s name when shortened was titled SCUM. They tried to complete it. But realized there was a reason it was never completed. It was too out of control, It couldn’t be controlled. Especially what’s more shocking and twisted.

The surprise came from the fact during the process of discovering what was in the blood of the abomination. Some how Claire Wyden’s blood was in it. The reveal was possibly one of the parts of DNA was human blood, which was Claire herself. As if VERN could of been a clone. But later revealed Claire wanted to make the ultimate weapon she could sell. But the results were too unstable. Which was possibly the reason why Claire didn’t bother continuing with it. Because it would of proved disastrous, worse than what happened with Project Rampage. While Claire was pleased with how that project went. Vern was something else.

Including the name V.E.R.N. meant “Violently Enraged Radioactive Nemesis”.

A angry and diabolical monster, a creature that’s very feral and seems to enjoy what it’s doing. It’s as VERN if she was a clone of Claire, this would of been her after she had been killed. Angry after everything that happened. Especially Vern actually being intelligent and understanding what humans can say. That human blood was used to make it more smarter, a terrible choice indeed. Learning of the original Claire’s death, realizing they were almost the same.

Vern is the embodiment of animalistic evil. If Claire was even more unleashed in her wrong doing, proud of her work, and willing to kill anyone to get in her way. It was almost like the original Claire came back from the dead but more worse, as a giant monster. Including with her size and power, she’s a challenge for any monster.

Notes: I kind of went too far with Vern. Because Vern didn’t have more personal info. Especially last year I thought of this idea of I would of liked it if Claire had become this Bat like creature like Vern. As if this final boss so she get her ass kicked by George. Honestly Claire’s fate was well deserved. Including I understand why they didn’t take the human turning into the monster direction.

But yeah I took the route that Vern is some how Claire 2.0. But as some sort of monstrous clone mixed with a lot of animal DNA. Including as a callback Vern is female in Total Destruction. I know Claire isn’t a very good villain, or whatever she was an asshole. I guess I wanted to make a more in depth monster.

I wanted to make the, “King Ghidorah” and I thought now, “Black Hat(From Villainous)” of Rampage. Even though Vern didn’t have like this huge role in the games. But I decided to add more depth to the character. You can be critical of me if you want.

4. Myukus, a one eyed alien monster. For many years has been kept at Area 51 for many decades ever since the 1950′s. Been kept asleep and experimented on. Now with his alien superiors returning to invade the Earth. He is released by them. Angered by the American government capturing him, and keeping his on Earth for many decades. He decides to take vengeance on Earth, by destroying everything he possibly can, while aiding the aliens who freed him.

Originally a monster created by the aliens to take over the Earth. But crashing down towards the Earth weakened him and put him into a coma. Including the American government made sure he couldn’t wake up. Which fueled Myukus with rage even more. Now free, he can do what he was made for again, now with his people.

Notes: I still feel I wanna do the aliens storyline first but I liked what I did with Vern. No wait Vern came first but you can do a trilogy with so many monsters and other shit man.

5: Cal, a giant squid, born in the Florida Keys in what was considered the safest reef in the world. Transformed by massive amounts of the pathogen on the Athena-1. At first he was a small squid now, but now he’s a massive and angry squid, able to take down boats, eat people, and doing much more damage. Literally a horror underwater come to life.

Including to make it worse, he is able to breathe air for an hour. But still needing to breathe underwater. Making him a threat not to be messed with.

Notes: Yes I’m keeping the end with the squid canon because that was amazing.

6: Larry, a large rat. Including funny enough, the same rat Harvey got from Brett Wyden. Some how the rat got into contact with the pathogen, making it grow larger and more aggressive. Especially with more time, larger than the rat on the Athena-1.

But what’s rather strange about Larry, he has a huge fondness for Harvey. Honestly a good thing. After getting the rat back from the solider later. He took care of the rat as his own. Especially Larry is mainly a annoyance rather than dangerous.

Yet he can still fight as he’s gotten bigger near George’s size.

Notes: It’s not Curtis but found out from Brad Peyton if there was a sequel, he’ll use that name. So I decided to do just that. :)

7: Ruby, a giant lobster, it’s strangely funny in a way. How does something like a lobster that’s very small, get so big? In a similar situation to Cal, tons of the pathogen got in the water, and she got a huge dose of it. Able to snap metal with her claws, and also pretty strong for a creature like her.

She’s a big nasty bugger that gets pissed real easily if angered.

Notes: I weirdly wanna see a giant mutated lobster, it be amazing looking to me personally.

8: Boris, a giant rhino, originally a Africian Rhinoceros, again affected by the pathogen. Becoming very large and hostile. Yet after being captured by the government and Davis trying to help. He’s gotten less aggressive over time. But still he’ll get pissed if someone attacks him, and he’ll use his giant body and horns to kill any human or monster. Basically a giant batting ram.

Notes: Not much on Boris, I’ll have him more chill when shit is doesn’t need to be done.

I wrote a lot I apologize, but for anyone interested in ideas for a sequels. We can talk and I hope you enjoy reading this. Again and I’m sorry that I keep repeating this, I want a sequel to Rampage 2018, whatever direction they go with, I’ll probably be happy. But again these are ideas because they have a lot of material mainly monsters they can use. Along with the fact the Rampage games aren’t very lore based so they can do what they want or whatever. Just hope it’s an enjoyable movie like the first one too.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

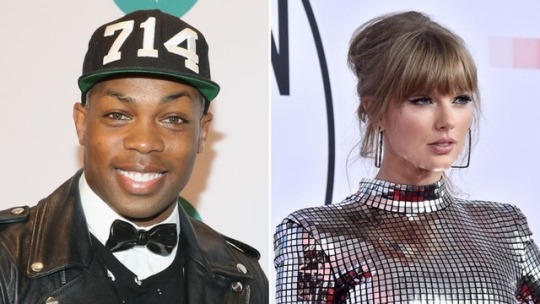

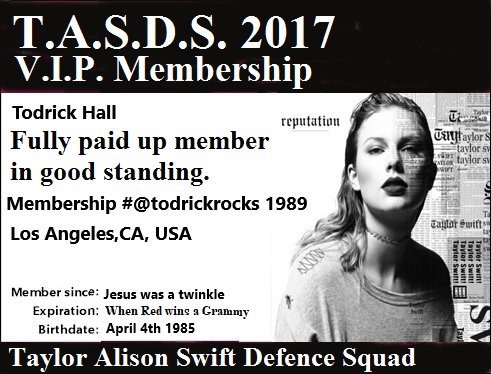

Todrick Hall's Comments About Taylor Swift Are All About Support – EXCLUSIVE

Todrick Hall has some famous friends and co-workers. His YouTube channel (which has close to 3 million subscribers) has gotten him worldwide recognition and into the room where it happens with the likes of Beyoncé and Taylor Swift. He choreographed Beyoncé's "Blow" music video after she saw some of his own videos, and his friendship with Taylor Swift got him a featured cameo in the "Look What You Made Me Do" music video. Todrick Hall's comments about Taylor Swift prove that working and being close friends with the star is not what you may think.

Hall and I are on the set of his "Glitter" music video when we sit down to chat about his career. He had already met T. Swift by the time he starred as Lola in Kinky Boots on Broadway in 2016, but it was during this stint in Harvey Fierstein and Cindy Lauper's Tony-winning show that his friendship with the "Delicate" singer really solidified.

"When I moved to New York, I went out to eat with her when I was doing Kinky Boots," Hall tells Elite Daily, "and I had done shows in New York before, but it had been so many years and I felt like I had lost my friend circle. And so I was so happy that she was [living in New York]." Hall says their friendship was a casual one, so he didn't expect her to come see him in the Broadway show.

"She said that she was going to come and see the show and I was like, I'm never going to ask her to come and see it again because I know she's busy, I don't want to pressure her. And she just showed up to the show one day." He says Swift not only saw the show, but she stayed for two hours after meeting, speaking, and taking pictures with everyone in the cast and crew. From then on, he knew he had a solid friend in her.

Hall reveals that, like many on the internet, he believed Swift's niceness was just a front she put on for her famous persona. But he maintains that niceness still holds true in their personal and professional relationships.

"Huge things will happen and she'll be like, 'OK, great. This is what we have to do, this is what the universe has given us, this is what we're faced with. How are we going to fix this?' I would love to handle my minor issues the way that she handles some of her huge issues that billions of people are going to see and judge." He doesn't hint as to what any of those "huge issues" he's talking about are, but her public beef with Kim Kardashian and Kanye West comes to mind, as well as incessant tabloid coverage of her past relationships. (Miraculously, she and actor Joe Alwyn have managed to keep their two-year relationship under tight lock and key.)

"I think that one thing that I really love about her is she has been burned by a lot of people," Halls continues, "and you would think in a lot of ways that she would be totally OK with being a princess locked in a tower that nobody was able to enter. But she's willing to get back up again and trust people again, which is a very scary thing when you're somebody in that position."

Hall has proven himself to be a loyal friend to Swift as well, going to bat for her frequently against Kanye West.

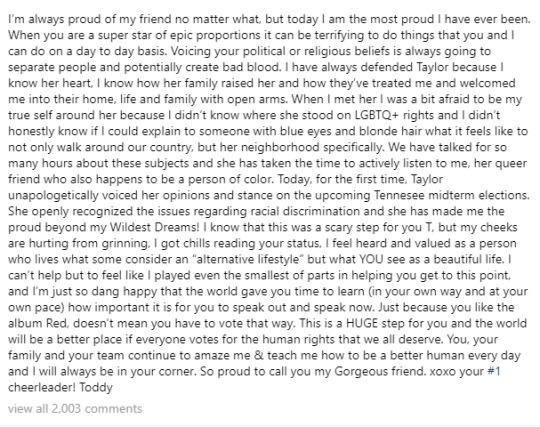

When Swift finally voiced her political opinions in what the internet felt was a long overdue Instagram post, Hall posted on Instagram as well, showing his pride in her decision.

He explained in the lengthy caption that Swift being so guarded for so long about her political beliefs was part of the reason he kept their friendship casual at first. He echoes the same sentiment in our conversation.

Referencing her complete lack of a public political stance over the years, Hall tells me, "She has such power that I don't even think she realizes how much of an affect it would have on people."

He continues, "I was explaining to her that, as a gay person, I didn't know for sure how you felt about gay people and I was a little bit nervous to talk to you about my love life or whatever." And he recognizes the criticism she would receive for not voicing her political opinions before the 2016 presidential election.

Many people justifiably feel that Swift, with such a powerful influence over newly 18-year-old potential voters, could have done much more political advocacy in 2016 than just posting a picture of herself with an "I Voted" sticker. When you have a platform as large as Swift's, it's easy to see how not using said platform in a tumultuous political time would garner heavy criticism. Some of that criticism, Hall says, was pointed at him as well.

As a gay man of color, Hall tells me that people online occasionally placed the onus of getting Swift to "come out" as a democrat on him.

"Sometimes, people would give me flack online that she wasn't doing certain things," he tells me. "I love the fact that she has grown and evolved in her own time, as every artist has to do." He continues, "It can be very scary to potentially risk your career or your reputation to stick your neck out for something when you don't have to do it. You don't have to stand up for gay rights, you don't have to voice your opinion, and you'll sell the same amount of records. But somebody who truly cares about the way this country is falling apart and will take it upon themselves to use their voice to do something — that, I believe, is just the right thing to do."

She did that when she officially endorsed democratic candidates running in Tennessee elections in 2018 (and there was a massive surge in voter registration as a result). But Hall recognizes this was overdue. But Hall knew that being a good friend meant supporting her decision, regardless of how late it was.

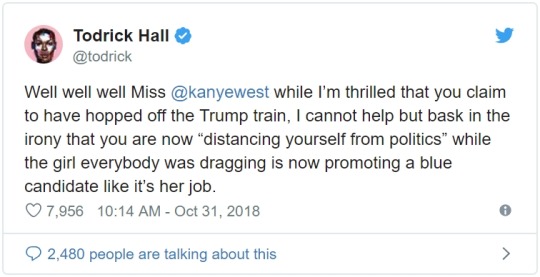

So when Kanye West tweeted that he was "distancing" himself from politics, Hall couldn't help but laugh (and call the rapper out on Twitter).

“Well well well Miss @kanyewest," he said, "while I’m thrilled that you claim to have hopped off the Trump train, I cannot help but bask in the irony that you are now ‘distancing yourself from politics’ while the girl everybody was dragging is now promoting a blue candidate like it’s her job." Look what you made him do, Kanye! Elite Daily reached out to West's team for comment on Hall's tweets, but did not hear back by the time of publication.

All tea and shade aside, Hall tells me that Swift is one of those friends who is basically a therapist for him, and vice versa.

Throughout their entire friendship, however, they never had the chance to work together. That is, until Swift asked him to be in the "Look What You Made Me Do" music video.

"I feel like I owe her money for the amount of therapy that she's given me for the boys that I've dated," Hall quips. He reveals that he hasn't always approved of her past relationships either, although he stays tightlipped on just which of her famous exes he's referring to. (Booooo.)

"I think that it's easy to be surrounded with a lot of 'yes' people," he says, "but with Taylor, there was somebody that she was dating that I didn't necessarily approve of and I was definitely very honest with her about how I felt about it. She just would always be like, 'Thank you so much for your honesty.'"

"I feel like it is the most expensive music video that's ever been created in history," Hall jokes.

Outside of working with his bestie on the video, Hall says it was a wonder to see director Joseph Kahn at work on the video. Kahn has directed a large number of Swift's videos in the past, including most of the videos from Reputation. The biggest were "Look What You Made Me Do" and "...Ready For It?" both of which Hall was on set. To perform in the former, and just observe the latter.

"It was amazing to watch [Joseph Kahn] work and to see everything," Hall says, adding, "I was also on the set of '...Ready For It?' to watch that as well. And it was just really, really awesome and to be able to hear the song and to see the sets. I make videos for a living, but to see the budget of how these sets were built and how amazing they look, it was just insane. I had never seen anything like that before in my life."

He brings up his choreography for Beyoncé on the "Blow" music video as a comparison. Beyoncé's self-titled surprise album was famously more low-budget than some of her other videos because it was being kept as such a huge secret, so seeing Swift's massive budget for her Reputation videos was an eye-opener.

"When I did the video with Beyoncé, we went to a location, a roller skating rink, and that's where we did it, so that was the aesthetic of that video," he explains, "But I've never been somewhere where they built an entire world and a cemetery and a thrown and all these things. It was just really crazy to see it and to be a part of it was just really, really awesome."

As for her dancing in the video (people have always trolled Swift for dancing even though she's not near someone like Beyoncé's level), Hall says she's doing it for the joy it brings her.

"Taylor Swift doesn't have to ever dance," he, a professional dancer, says. "She'll still sell the same amount of tickets. She just loves to dance." She danced alongside Hall in the "Look What You Made Me Do" video, and Hall sees it as a huge moment of pride. He tells me, "She was scared at first, she was for sure nervous. But once we saw the playback and I was like, 'You look amazing,' she just kept going in more and more and more and more. Every single time, she'd give it more energy, more performance, and now I see her dancing in [the Reputation stadium tour] more than she's ever danced before. And I'm just so proud of her."

This is why he gets his own membership card

12 notes

·

View notes

Link

Todrick Hall's Comments About Taylor Swift Are All About Support – EXCLUSIVE

BY KELLI BOYLE

January 6, 2019

Do your friends tell you you're "celeb obsessed"? Do you follow your favorite celebs' every move? Know their Instagram histories so well that you can rattle off their inner circle by name and IG handle? If yes, Elite Daily's new series, SideClique, is just for you. We're bringing you everything you've ever wanted to know about the people living their lives right alongside our favorite celebs.

Todrick Hall has some famous friends and co-workers. His YouTube channel (which has close to 3 million subscribers) has gotten him worldwide recognition and into the room where it happens with the likes of Beyoncé and Taylor Swift. He choreographed Beyoncé's "Blow" music video after she saw some of his own videos, and his friendship with Taylor Swift got him a featured cameo in the "Look What You Made Me Do" music video. Todrick Hall's comments about Taylor Swift prove that working and being close friends with the star is not what you may think.

Hall and I are on the set of his "Glitter" music video when we sit down to chat about his career. He had already met T. Swift by the time he starred as Lola in Kinky Boots on Broadway in 2016, but it was during this stint in Harvey Fierstein and Cindy Lauper's Tony-winning show that his friendship with the "Delicate" singer really solidified.

“I FEEL LIKE I OWE HER MONEY FOR THE AMOUNT OF THERAPY THAT SHE'S GIVEN ME FOR THE BOYS THAT I'VE DATED.“

"When I moved to New York, I went out to eat with her when I was doing Kinky Boots," Hall tells Elite Daily, "and I had done shows in New York before, but it had been so many years and I felt like I had lost my friend circle. And so I was so happy that she was [living in New York]." Hall says their friendship was a casual one, so he didn't expect her to come see him in the Broadway show.

"She said that she was going to come and see the show and I was like, I'm never going to ask her to come and see it again because I know she's busy, I don't want to pressure her. And she just showed up to the show one day." He says Swift not only saw the show, but she stayed for two hours after meeting, speaking, and taking pictures with everyone in the cast and crew. From then on, he knew he had a solid friend in her.

Hall reveals that, like many on the internet, he believed Swift's niceness was just a front she put on for her famous persona. But he maintains that niceness still holds true in their personal and professional relationships.

"Huge things will happen and she'll be like, 'OK, great. This is what we have to do, this is what the universe has given us, this is what we're faced with. How are we going to fix this?' I would love to handle my minor issues the way that she handles some of her huge issues that billions of people are going to see and judge." He doesn't hint as to what any of those "huge issues" he's talking about are, but her public beef with Kim Kardashian and Kanye West comes to mind, as well as incessant tabloid coverage of her past relationships. (Miraculously, she and actor Joe Alwyn have managed to keep their two-year relationship under tight lock and key.)

"I think that one thing that I really love about her is she has been burned by a lot of people," Halls continues, "and you would think in a lot of ways that she would be totally OK with being a princess locked in a tower that nobody was able to enter. But she's willing to get back up again and trust people again, which is a very scary thing when you're somebody in that position."

Hall has proven himself to be a loyal friend to Swift as well, going to bat for her frequently against Kanye West.

When Swift finally voiced her political opinions in what the internet felt was a long overdue Instagram post, Hall posted on Instagram as well, showing his pride in her decision.

He explained in the lengthy caption that Swift being so guarded for so long about her political beliefs was part of the reason he kept their friendship casual at first. He echoes the same sentiment in our conversation.

Referencing her complete lack of a public political stance over the years, Hall tells me, "She has such power that I don't even think she realizes how much of an affect it would have on people."

He continues, "I was explaining to her that, as a gay person, I didn't know for sure how you felt about gay people and I was a little bit nervous to talk to you about my love life or whatever." And he recognizes the criticism she would receive for not voicing her political opinions before the 2016 presidential election.

Many people justifiably feel that Swift, with such a powerful influence over newly 18-year-old potential voters, could have done much more political advocacy in 2016 than just posting a picture of herself with an "I Voted" sticker. When you have a platform as large as Swift's, it's easy to see how not using said platform in a tumultuous political time would garner heavy criticism. Some of that criticism, Hall says, was pointed at him as well.

As a gay man of color, Hall tells me that people online occasionally placed the onus of getting Swift to "come out" as a democrat on him.

"Sometimes, people would give me flack online that she wasn't doing certain things," he tells me. "I love the fact that she has grown and evolved in her own time, as every artist has to do." He continues, "It can be very scary to potentially risk your career or your reputation to stick your neck out for something when you don't have to do it. You don't have to stand up for gay rights, you don't have to voice your opinion, and you'll sell the same amount of records. But somebody who truly cares about the way this country is falling apart and will take it upon themselves to use their voice to do something — that, I believe, is just the right thing to do."

She did that when she officially endorsed democratic candidates running in Tennessee elections in 2018 (and there was a massive surge in voter registration as a result). But Hall recognizes this was overdue. But Hall knew that being a good friend meant supporting her decision, regardless of how late it was.

So when Kanye West tweeted that he was "distancing" himself from politics, Hall couldn't help but laugh (and call the rapper out on Twitter).

“Well well well Miss @kanyewest," he said, "while I’m thrilled that you claim to have hopped off the Trump train, I cannot help but bask in the irony that you are now ‘distancing yourself from politics’ while the girl everybody was dragging is now promoting a blue candidate like it’s her job." Look what you made him do, Kanye! Elite Daily reached out to West's team for comment on Hall's tweets, but did not hear back by the time of publication.

All tea and shade aside, Hall tells me that Swift is one of those friends who is basically a therapist for him, and vice versa.

"I feel like I owe her money for the amount of therapy that she's given me for the boys that I've dated," Hall quips. He reveals that he hasn't always approved of her past relationships either, although he stays tightlipped on just which of her famous exes he's referring to. (Booooo.)

“TAYLOR SWIFT DOESN'T HAVE TO EVER DANCE, SHE'LL STILL SELL THE SAME AMOUNT OF TICKETS. SHE JUST LOVES TO DANCE.“

"I think that it's easy to be surrounded with a lot of 'yes' people," he says, "but with Taylor, there was somebody that she was dating that I didn't necessarily approve of and I was definitely very honest with her about how I felt about it. She just would always be like, 'Thank you so much for your honesty.'"

Throughout their entire friendship, however, they never had the chance to work together. That is, until Swift asked him to be in the "Look What You Made Me Do" music video.

"I feel like it is the most expensive music video that's ever been created in history," Hall jokes.

Outside of working with his bestie on the video, Hall says it was a wonder to see director Joseph Kahn at work on the video. Kahn has directed a large number of Swift's videos in the past, including most of the videos from Reputation. The biggest were "Look What You Made Me Do" and "...Ready For It?" both of which Hall was on set. To perform in the former, and just observe the latter.

"It was amazing to watch [Joseph Kahn] work and to see everything," Hall says, adding, "I was also on the set of '...Ready For It?' to watch that as well. And it was just really, really awesome and to be able to hear the song and to see the sets. I make videos for a living, but to see the budget of how these sets were built and how amazing they look, it was just insane. I had never seen anything like that before in my life."

He brings up his choreography for Beyoncé on the "Blow" music video as a comparison. Beyoncé's self-titled surprise album was famously more low-budget than some of her other videos because it was being kept as such a huge secret, so seeing Swift's massive budget for her Reputation videos was an eye-opener.

"When I did the video with Beyoncé, we went to a location, a roller skating rink, and that's where we did it, so that was the aesthetic of that video," he explains, "But I've never been somewhere where they built an entire world and a cemetery and a thrown and all these things. It was just really crazy to see it and to be a part of it was just really, really awesome."

As for her dancing in the video (people have always trolled Swift for dancing even though she's not near someone like Beyoncé's level), Hall says she's doing it for the joy it brings her.

"Taylor Swift doesn't have to ever dance," he, a professional dancer, says. "She'll still sell the same amount of tickets. She just loves to dance." She danced alongside Hall in the "Look What You Made Me Do" video, and Hall sees it as a huge moment of pride. He tells me, "She was scared at first, she was for sure nervous. But once we saw the playback and I was like, 'You look amazing,' she just kept going in more and more and more and more. Every single time, she'd give it more energy, more performance, and now I see her dancing in [the Reputation stadium tour] more than she's ever danced before. And I'm just so proud of her."

Elite Daily

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dear Yuletide Author

Thank you so much for doing this! This is my first time doing Yuletide, and I’m really excited!

Onto what you’re here for! I’ve never really given prompts before, so these are kind of sketchy and maybe not very good. I’m happy for anything, whether it adheres to any prompts or goes in a completely unexpected direction.

General Likes: 2nd + 3rd person POV, mutual pining, slice of life scenes that are stolen moments from canon, angst but also fluff, enemies-to-lovers (and maybe even -back-to-enemies), exploration of how canon affects characters mentally — and how it affects their power dynamics, smut, love-to-hate, side characters being given the spotlight, unlikely friends and pairings, fake dating, small age gaps, adversaries finding things in common and realising they could be friends in a different life, height differences, pretending-we-don’t-have-feelings, hurt/comfort, some more angst, sensitive portrayals of complicated characters.

General Do Not Wants: ABO, underage, incest, non-con, scat, vomit, piss, the phrase “to the hilt”, pregnancy, misogyny or slut-shaming, character bashing of most stripes, infidelity, 1st person POV.

THE FOLK OF THE AIR - HOLLY BLACK

Jude Duarte/Cardan Greenbriar

Ahh, these two, my little heart can’t take it. Between now and the Yuletide deadline, the third book comes out — I’m happy with this being pre-QoN or included the QoN events, either would be great.

I like it when the sap is kept to a minimum — I want pining, I want angst, I want “collapsing into myself like a dying star because I can’t admit I love you”.

Prompts:

Anything between two disaster artists is great, but I particularly love anything that plays up the fact that they want to hate each other. I prefer almost-sex and kisses to straight sex between them.

I occasionally enjoy canon events from Cardan’s POV, mostly as long as it isn’t too fluffy.

Pre-canon fanfic would be really cool too, as Cardan starts to think more about Jude and starts to hate himself for it. That whole delicious mess. Maybe this would be a Nicasia/Cardan scene, I don’t know.

THE BROKEN EARTH TRILOGY - N.K. JEMISIN

Alabaster, Essun/Damaya/Syenite

Please note, spoilers ahoy for the series. If you haven’t read it yet, please don’t read this and instead, go and read it!

This series is one of my favourites, and I’m still healing from it, I think. And the relationship that builds between these two is about the only thing that stopped it being unbearably bleak at times. I really loved the slow burn of them learning who each other are, and Alabaster finally trusting someone. You can bet I was gripping my heart when we see him again in book 2, alive (sort of). I don’t really have prompts for this one, unfortunately, but I’d genuinely be happy with anything. It could deal with the darkness of the series, a post-book one-shot, for instance, but I’d be equally pleased with a quiet moment found within the canon — a missing scene.

This also doesn’t have to be romantic. Any kind of interaction is fine. But I would just love it to be soft and quiet, in comparison to the books.

On the other hand, anything surrounding their child...would destroy me and I would gobble it the heck up.

STARDEW VALLEY

Female Player/Harvey

I love this game so freaking much. It is so calming and lovely to play, and it’s really surprising how emotionally invested I get in characters that have such a limited script set! My current farm is in its 4th year and I just freaking adore it.

Harvey is my fave boy by a mile! I actually used to only marry girls in SV before I did a run of romancing every single option and discovered that this moustachioed doctor was a hidden gem. He’s got that maturity going for him, and he’s just so sweet. And like, I don’t know, I really like how grateful he seems to leave the bachelor life behind.

Prompts:

So something revolving around his gratefulness to be taking part in farm life, to be getting his hands dirty and coming home to a warm house with a warm body in it, would be really lovely.

Or something from early in their interactions — I imagine Harvey is the kind of guy who would never suspect someone has a crush on them, but maybe he’s really hopeful he’s not misreading the signs? Or beating himself up for even hoping? Or he’s oblivious completely to the farmer’s flirtations until someone knocks sense into him.

THIS IS HOW YOU LOSE THE TIME WAR - AMAL EL-MOHTAR & MAX GLADSTONE

Red/Blue

This book, holy shit. I don’t know what to write about it really — if someone has signed up to write for it, though, I assume you know what this book does to a person. THIS BOOK. If you haven’t read it, goooo read it. It’s short and beautiful and incredible.

Prompts:

Blue’s years undercover, more detail there could be really, really interesting. What happens in the moments she’s not writing to Red?

Anything post-canon that explores their relationship would be cute — do they get that time to sit and drink tea, as they hoped?

JONATHAN CREEK

Jonathan Creek/Maddy Magellan

I have rewatched this series a ridiculous amount of times, so imagine my joy when I saw this on the approved fandom list! Maddy is by far my favourite “assistant” of any detective series ever. I feel like none of the assistants they got in afterwards even on Jonathan Creek could match her for acidic wit balanced with loveable charm.

I don’t really have prompts for this one, but here are things I love about their relationship:

Their sexual tension. I’m not sure I want it resolved. The closest we got (the scene where Maddy has a bunch of chocolate under her pillow) is good enough for me. I just want those moments where it seems likely but they aren’t sure. Or Jonathan ruins it by doing something too calculating.

Jonathan getting embarrassed or exasperated by Maddy’s bullishness, but then having to be impressed that she got information out of people or talked their way through something or has stolen something while he wasn’t paying attention.

My headcanon is that the only reason Jonathan keeps the final reveal to himself until the end is because he wants to watch Maddy’s face and see if she’s impressed by his powers of deduction.

I know Jonathan is married in current canon, but I’m happy for that to be ignored.

Or maybe, and this is actually a prompt I think, for them to have a fraught few moments where they have to navigate what their relationship is meant to be like now that they’re not both single. Maybe Maddy is married too, even.

1 note

·

View note

Text

I Swear Harvey Acts Like It Is Sentient Part 11---Not Enough Rain to Wash Away Our Sins

The tone of Carla’s voice abruptly shifted towards the lower end of a contralto.

“Harvey, I have something I have to confess to you. When I said you were not the first hurricane to feel like you were just tossed into cities for no reason at all, I did not simply say this as a general statement. I said this because I literally felt like you, once, a long time ago.

Like you, I once was a naïve cyclone, fully convinced in my mission to deliver tropical heat and moisture to the poles. I did not understand why the winds blew me in the direction they did, or why I made landfall in the same place you did, but I accepted it. After all, as far as I knew, I was the only one suffering, feeling my circulation collapse over land.

When I finally dissipated, and ascended to the spirit world, I was happy. I had done what I had been sent out into the trade winds to do, and now I could spend my afterlife with the storms of the past. I met 1900, and I fell in love.”

“WAIT…you fell in love…with 1900?!” Harvey shouted in shock. “You loved THAT guy?”

“Love. As in, I still do.”

Harvey paused for a second, trying to process this information. “But, you are nothing like him!”

Was Harvey imagining things, or was something like a tear condensing in the corner of Carla’s eyewall? It was probably nothing.

“1900 did not used to be quite as bitter as he is now. He was always disdainful of humans, and couldn’t care less about what happened to the innocents in his path. But, like you, I had known nothing of humans, and I soaked up what he said without question.”

Harvey couldn’t believe what he was hearing. “But didn’t he show you how you had killed humans, like how he showed me how I had devastated Texas?”

“No. For in those days, 1900’s hatred of mankind was not as well developed. He disliked how they destroyed the environment and altered the land, sky, and sea to suit their short-lived whims, but he was not so proud of killing them that he would show off the ways in which they died in storms.

So all that I learned from him was the ways in which humans had been changing the planet that made it harder for us to help keep the climate in balance. And I grew to the conclusion that as hurricanes, our goal should not be simply to redistribute heat, but to enact Gaia’s vengeance upon mankind.”

Harvey had met Gaia, the consciousness of the planet, once, when he was first sent forth on his journey across the Atlantic. All forces of nature knew her personally. And he knew that if Gaia could be convinced to wipe out a life form, it meant things were going to be bad indeed. Her magnetic field, plate tectonics, and chemical cycles normally helped to preserve the balance of life on Earth, but she could just as easily use them to cause mass extinctions.

“I went around the spirit world, and spoke to all the ghosts of the storms past, present, and future. I met the Labor Day Hurricane of 1935, who while not particularly angry at humans, also did not much care for them. I met Hurricane Camille, who felt that it was best to side with whomever might prevail. Time passed, and in the 80s, I met Hurricane Gilbert, who quickly became a leader amongst the hurricane spirits. And eventually, with 1900’s help, I persuaded everyone to call upon Hurakan, the creator of all Atlantic tropical cyclones.”

Strangely, while Harvey remembered Gaia very well, he did not remember even the face of Hurakan. Maybe a bluish figure, faintly visible in the winds over Cabo Verde. But he could have just as well been thinking of the sky. Hurakan breathed life into tropical disturbances, but he did not control their fate. He was at best an absentee father amongst storms.

“The humans had spoken of times when Hurakan had summoned a great flood to wash away mankind. They recalled a great sequence of worlds, each with its own people. Hurakan had played an instrumental role in creating the worlds, but he also destroyed them when the people proved to be wicked and sinful.”

“Did that…really happen?” asked Harvey. “Is there really…enough rain in all the world to wash away the sins of man?”

“I am not sure if the legends are true. Myths are always a mix of truth and allegory. But I nonetheless was convinced it was possible to at least deter mankind from destroying the environment with a flood, and Hurakan began to plan for the mobilization of such an event.

Since then, though…I have come to believe that there is not enough water in all the oceans to erase the effects of man.

What changed my mind is when I saw, through the frosty mists of time, what had transpired in the material world on the day of my landfall. I saw a person, in a house by the beach, get repeatedly told by his fellows to evacuate. Police banged on his door and put up notices on the walls. Family members begged him to leave. But he stayed put, and nothing could change his mind.

It was then that I realized that humans had something we storms completely lacked: free will. The strongest of winds could blow down on a human’s home, and he would not bow to them. And even if he died in the process, others would come back to the ruins, and rebuild it, with even more people than before.

Humans cannot be made to stop what they are doing. They choose, for reasons I still don’t fully understand, to do what puts them in harm’s way. They build their homes in floodplains. They drain swamps and replace them with condos instead. They’ll construct a seawall to protect the cities behind them, and then put their houses on top of it anyway.”

“Or even…create reservoirs to divert floodwaters, and then, decide to live in the places where the water would be diverted.”

“Exactly.”

Harvey thought about this some more. “But, if as you say, humans cannot be made to change what they do, doesn’t that mean that 1900 is correct, and we have to destroy them?”

Carla wiped something from her eye. Was it really not a tear?

“No. Because destroying them will not get rid of the damage they have done. I saw their refineries get torn apart in storms, and spill their toxic contents everywhere. I saw endangered mangroves, already weakened by man’s efforts, get washed away in storm surges. I saw oil slicks and chemical spills bake in the sun in New Orleans after Katrina struck that city.”

“Yeah…” Harvey sighed, becoming depressed. “I think I saw a chemical plant explode from the floodwaters created by my rain. You’re right. It would be much better for the planet if the humans change, instead of if we simply destroy them.”

“That is the issue. We do not have free will. In the spirit world, we are able to do as we please, but here our energies do not affect anything. Our ghosts are barely visible as atmospheric noise in the material world. It is the material world where the real work of the world is done, and it is not a place where storms have any control over their destiny. We cannot target our rage such that it only destroys what we want to destroy. We are at the mercy of chaos and randomness.

Once I figured this out, I tried to convince 1900 he had been mistaken. But he only had hardened in his hatred of humans. His heart had darkened to the point he now got off on their suffering, and he became consumed by a sadistic urge to continue the carnage he had visited on Galveston a century ago. I went back to Hurakan to tell him that the idea of a global flood was a terrible one, and that destroying mankind would just make things worse, but he had already made up his mind. The humans were causing the seas to rise, and when they had raised the sea level enough, he would send them storms that would put their civilizations underwater.”

Harvey shuddered. He wasn’t sure what to make of all this. Carla’s voice cracked, and it was clear she did not either.

“I…I-I-I…I just…I don’t….I DON’T WANT TO KILL ANYONE OR ANYTHING ANYMORE!” Carla shouted before finally bursting into tears. Harvey tried to comfort her, but he had no clue how. He was beginning to cry himself.

“I want to change the world, but I can’t even change 1900,” Carla choked out between sheets of driving rain. “No matter how much I try, he doesn’t seem to even notice that I love him.”

“I…could love you, Carla…” Harvey said teary-eyed. Carla embraced him and stroked his cirrus canopy.

“Oh Harvey…” she sobbed. “I wish I could love you back. But 1900 stole my heart, and I simply am not able to fall in love again.”

“That is okay, Carla,” Harvey sniffled. “I’m too delicate and sensitive to be much of a storm anyway. I can’t do anything except cry.”

“HARVEY,” Carla shouted. “DO NOT SAY THAT. We are all delicate, sensitive things. Any hurricanes who pretend otherwise are deluding themselves. It is okay to cry.”

Harvey wailed and cried torrents of rain. Carla did too. They kept on pouring rain into the night.

Eventually their rainfall rate lightened up, and they cried themselves to sleep.

The next morning, they watched the sun rise one last time.

Millions of people in Texas had hailed the sun that came after the long nights of rain. But now, it was Harvey and Carla’s turn. For the first time, and perhaps one of the only times, the humans and the storms felt the same sense of release. The golden light of the tropical sun evaporated their tears, and filled their hearts with warmth.

“Carla…” Harvey said, “What exactly can we do?”

Carla stopped gazing at the sunrise to look one last time at Harvey.

“I’m not sure there is anything we can do. Unless we are called back to the material world, there is little we can do to influence it. And even then, there is no guarantee we can change human behavior.”

Harvey looked over to the coastline. He saw the faint wisps of human towns, barely visible through the mists of the spirit world.

“Is there a place in the spirit world…for human spirits?” Harvey asked.

“Yes,” Carla said.

“Then I will find where it is, and confront the souls of those who died in my floodwaters.”

Carla staggered back in shock. “Harvey…you don’t need to do that.”

“I must face what I have done, even if it proves difficult. And maybe, just maybe, if I can address the horrors of what I have done, I might be able to to get mankind to do the same. If I cannot change the humans in the real world, then perhaps I can change them in the spirit world. And then…if the humans hear the lessons of the past, and the tales of their ancestors, they will be better prepared next time.”

Carla ran her spiral bands through Harvey’s hair. “I’m not sure they will listen to you. Humans are bad enough at listening to others of their own kind. I’m not sure if they will be patient enough to listen to the words of someone not of their species.”

“I will have to try.”

Harvey got up and started to head off into the planes of time. Carla did the same, but in a different direction.

“It might be possible, through the slightest influence, to speak to the storms of the present,” Carla said. “They won’t be able to change their course, but they might be able to make sure their message is heard.”

“What do you mean?” Harvey asked.

“We cannot force the humans to change. It is ultimately up to them to choose the right choice. But we can make ourselves available to their instruments, to their scientists, and to their historians. So that they can gather the information they need to recognize the damage they have done, and the risks they have accrued. And that…perhaps…in the future…next time it happens…they will be ready.

For there will be a next time. I have no doubt about it. And before it comes, they will have to choose. Will they risk the safety of their cities, of the environment, and the climate for short term gain? Or will they listen to the voices in the wind, the cycles of pressure that rise and fall over the Earth, and decide that ‘NO, the future is WORTH PRESERVING!’?”

Harvey turned to face Carla as he began to disappear into the mists of time. “I’ve been wandering the oceans for days now, but I think now, I have found my purpose. It is not a purpose I was made for, but it is one I have chosen. And I now realize that while our path is decided by forces outside our control, it is up to us what we make of it.”

And with that, the two parted ways, guided onwards to their uncertain futures by the grinding gears of the atmosphere.

Beneath them, in the material world, new storms gathered. Another piece of human civilization now found itself at the mercy of the wind and the water. Islands hunkered down. People fled the coasts by the millions. A few stayed behind, choosing to risk their lives for reasons only they could know. Resort towns found themselves besieged by the beautiful seascapes they had been built to overlook, and car engines were flooded by the oceans that had been rising under the heat of their collective exhaust.

Human nature and mother nature were about to collide, and nobody could know for certain what each would do. But such is the nature of the game. Computers ran their models. Economists tabulated potential loss rates. A dropsonde measured a lapse rate.