#beets

Text

[ID: A circle of overlapping semi-circular bright pink pickles arranged on a plate, viewed from a low angle. End ID]

مخلل اللفت / Mukhallal al-lifit (Pickled turnips)

The word "مُخَلَّل" ("mukhallal") is derived from the verb "خَلَّلَ" ("khallala"), meaning "to preserve in vinegar." "Lifit" (with diacritics, Levantine pronunciation: "لِفِتْ"), "turnip," comes from the root "ل ف ت", which produces words relating to being crooked, turning aside, and twisting (such as "لَفَتَ" "lafata," "to twist, to wring"). This root was being used to produce a word meaning "turnip" ("لِفْتْ" "lift") by the 1000s AD, perhaps because turnips must be twisted or wrung out of the ground.

Pickling as a method of preserving produce so that it can be eaten out of season is of ancient origin. In the modern-day Levant, pickles (called "طَرَاشِيّ" "ṭarāshiyy"; singular "طُرْشِيّ" "ṭurshiyy") make up an important culinary category: peppers, carrot, olives, eggplant, cucumber, cabbage, cauliflower, and lemons are preserved with vinegar or brine for later consumption.

Pickled turnips are perhaps the most commonly consumed pickles in the Levant. They are traditionally prepared during the turnip harvest in the winter; in the early spring, once they have finished their slow fermentation, they may be added to appetizer spreads, served as a side with breakfast, lunch, or dinner, eaten on their own as a snack, or used to add pungency to salads, sandwiches, and wraps (such as shawarma or falafel). Tarashiyy are especially popular among Muslim Palestinians during the holy month of رَمَضَان (Ramaḍān), when they are considered a must-have on the إِفْطَار ("ʔifṭār"; fast-breaking meal) table. Pickle vendors and factories will often hire additional workers in the time leading up to Ramadan in order to keep up with increased demand.

In its simplest instantiation, mukhallal al-lifit combines turnips, beetroot (for color), water, salt, and time: a process of anaerobic lacto-fermentation produces a deep transformation in flavor and a sour, earthy, tender-crisp pickle. Some recipes instead pickle the turnips in vinegar, which produces a sharp, acidic taste. A pink dye (صِبْغَة مُخَلَّل زَهْرِي; "ṣibgha mukhallal zahri") may be added to improve the color. Palestinian recipes in particular sometimes call for garlic and green chili peppers. This recipe is for a "slow pickle" made with brine: thick slices of turnip are fermented at room temperature for about three weeks to produce a tangy, slightly bitter pickle with astringency and zest reminiscent of horseradish.

Turnips are a widely cultivated crop in Palestine, but, though they make a very popular pickle, they are seldom consumed fresh. One Palestinian dish, mostly prepared in Hebron, that does not call for their fermentation is مُحَشّي لِفِتْ ("muḥashshi lifit")—turnips that are cored, fried, and stuffed with a filling made from ground meat, rice, tomato, and sumac or tamarind. In Nablus, tahina and lemon juice may be added to the meat and rice. A similar dish exists in Jordan.

Turnips produced in the West Bank are typically planted in open fields (as opposed to in or under structures such as plastic tunnels) in November and harvested in February, making them a fall/winter crop. Because most of them are irrigated (rather than rain-fed), their yield is severely limited by the Israeli military's siphoning off of water from Palestine's natural aquifers to settlers and their farms.

Israeli military order 92, issued on August 15th, 1967 (just two months after the order by which Israel had claimed full military, legislative, executive, and judicial control of the West Bank on June 7th), placed all authority over water resources in the hands of an Israeli official. Military order 158, issued on November 19th of the same year, declared that no one could establish, own, or administer any water extraction or processing construction (such as wells, water purification plants, or rainwater collecting cisterns) without a new permit. Water infrastructure could be searched for, confiscated, or destroyed at will of the Israeli military. This order de facto forbid Palestinians from owning or constructing any new water infrastructure, since anyone could be denied a permit without reason; to date, no West Bank Palestinian has ever been granted a permit to construct a well to collect water from an aquifer.

Nearly 30 years later, the Interim Agreement on the West Bank and the Gaza Strip (also called the Oslo II Accord or the Taba Agreement), signed by Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) in 1995, officially granted Israel the full control over water resources in occupied Palestine that it had earlier claimed. The Argreement divided the West Bank into regions of three types—A, B, and C—with Israel given control of Area C, and the Palestinian Authority (PA) supposedly having full administrative power over Area A (about 3% of the West Bank at the time).

In fact, per article 40 of Annex 3, the PA was only allowed to administer water distribution in Area A, so long as their water usage did not exceed what had been allocated to them in the 1993 Oslo Accord, a mere 15% of the total water supply: they had no administrative control over water resources, all of which were owned and administered by Israel. This interim agreement was to be returned to in permanent status negotiations which never occurred.

The cumulative effect of these resolutions is that Palestinians have no independent access to water: they are forbidden to collect water from underground aquifers, the Jordan River, freshwater springs, or rainfall. They are, by law and by design, fully reliant on Israel's grid, which distributes water very unevenly; a 2023 report estimated that Israeli settlers (in "Israel" and in the occupied West Bank) used 3 times as much water as Palestinians. Oslo II estimations of Palestinians' water needs were set at a static number of million cubic meters (mcm), rather than an amount of water per person, and this number has been adhered to despite subsequent growth in the Palestinian population.

Palestinians who are connected to the Israeli grid may open their taps only to find them dry (for as long as a month at a time, in بَيْت لَحْم "bayt laḥm"; Bethlehem, and الخَلِيل "al-khalīl"; Hebron). Families rush to complete chores that require water the moment they discover the taps are running. Those in rural areas rely on cisterns and wells that they are forbidden to deepen; new wells and reservoirs that they build are demolished in the hundreds by the Israeli military. Water deficits must be made up by paying steep prices for additional tankards of water, both through clandestine networks and from Israel itself. As climate change makes summers hotter and longer, the crisis worsens.

By contrast, Israeli settlers use water at will. Israel, as the sole authority over water resources, has the power to transfer water between aquifers; in practice, it uses this authority to divert water from the Jordan River basin, subterranean aquifers, and بُحَيْرَة طَبَرِيَّا ("buḥayrat ṭabariyyā"; Lake Tiberias) into its national water carrier (built in 1964), and from there to other regions, including the Negev Desert (south of the West Bank) and settlements within the West Bank.

Whenever Israel annexes new land, settlers there are rapidly given access to water; the PA, however, is forbidden to transport water from one area of the West Bank to another. Israel's control over water resources is an important part of the settler colonial project, as access to water greatly influences the desirability of land and the expected profit to be gained through its agricultural exports.

The result of the diversion of water is to increase the salinity of the Eastern Aquifer (in the West Bank, on the east bank of the Jordan River) and the remainder of the Jordan that flows into the West Bank, reducing the water's suitability for drinking and irrigation; in addition, natural springs and wells in Palestine have run dry. In this environment, water for drinking and watering crops and livestock is given priority, and many Palestinians struggle to access enough water to shower or wash clothing regularly. In extreme circumstances, crops may be left for dead, as Palestinian farmers instead seek out jobs tending Israeli fields.

Some areas in Palestine are worse off in this regard than others. Though water can be produced more easily in the قَلْقِيلية (Qalqilya), طُولْكَرْم (Tulkarm) and أَرِيحَا ("ʔarīḥā"; Jericho) Districts than in others, the PA is not permitted to transfer water from these areas to areas where water is scarcer, such as the Bethlehem and Al-Khalil Districts. In Al-Khalil, where almost a third of Palestinian acreage devoted to turnips is located [1], and where farming families such as the Jabars cultivate them for market, water usage averaged just 51 liters per person per day in 2020—compare this to the West Bank Palestinian average of 82.4 liters, the WHO recommended daily minimum of 100 liters, and the Israeli average of 247 liters per person per day.

As Israeli settlement גִּבְעַת חַרְסִינָה (Givat Harsina) encroached on Al-Khalil in 2001, with a subdivision being built over the bulldozed Jabar orchard, the Jabars reported settlers breaking their windows, destroying their garden, throwing rocks, and holding rallies on the road leading to their house. In 2010, with the growth of the קִרְיַת־אַרְבַּע (Kiryat Arba) settlement (officially the parent settlement of Givat Harsina), the Jabars' entire irrigation system was repeatedly torn out, with the justification that they were stealing water from the Israeli water authority; the destruction continued into 2014. Efforts at connecting and expanding Israeli settlements in the Bethlehem area continue to this day.

Thus we can see that water deprivation is one tool among many used to drive Palestinians from their land; and that it is connected to a strategy of rendering agriculture impossible or unprofitable for them, forcing them into a state of dependence on the Israeli economy.

Turnips, as well as cabbage and chili peppers, are also grown in the village of وَادِي فُوقِين (Wadi Fuqin), west of Bethlehem. In 2014, Israel annexed about 1,250 acres of land in Wadi Fuqin, or a third of the village's land, "effectively [ruling] out development of the village and its use of this land for agriculture." Most of this land lies immediately to the west of a group of settlements Israel calls גּוּשׁ עֶצְיוֹן ("Gush Etzion"; Etzion Bloc). Building here would link several non-contiguous Israeli settlements with each other and with القدس (Al-Quds; "Jerusalem"), hemming Palestinians of the region in on all sides (many main roads through Israeli settlements cannot be used by anyone with a Palestinian ID). [2] PLO executive committee member Hanan Ashrawi said that the annexation, which was carried out "[u]nder the cover of [Israel's] latest campaign of aggression in Gaza," "represent[ed] Israel’s deliberate intent to wipe out any Palestinian presence on the land".

This, of course, was not the beginning of this strategy: untreated sewage from Gush Etzion settlements had been contaminating crops, springs, and groundwater in Wadi Fuqin since 2006, which also saw nearly 100 acres of Palestinian land annexed to allow for expansion of the Etzion Bloc.

All of this has obviously had an effect on Palestinian agriculture. A 1945–6 British survey of vegetable production in Palestine found that 992 dunums were devoted to Arab turnip production (954 irrigated and 38 rain-fed; no turnip production was attributed to Jewish settlers). A March 1948 UN report claimed that "[i]n most districts the markets are well-supplied with all the common winter vegetables—cabbages, cauliflowers, lettuce and spinach; carrots, turnips and and beets; beans and peas; green onions, eggplants, marrows and tomatoes." By 2009, however, the area given to turnips in Palestine had fallen to 918 dunums. Of these, 864 dunums were irrigated and 54 rain-fed. This represents an increase in unirrigated turnips (5.8%, up from 3.9%) that is perhaps related to difficulty in obtaining sufficient water.

Meanwhile, Israel profits from its restriction of Palestinian agriculture; it is the largest exporter of turnips in West Asia (I found no data for turnip exports from Palestine after 1922, suggesting that the produce is all for local consumption).

The pattern that Ashrawi called out in 2014 continued in 2023, as Israel's genocide in Gaza occurs alongside the continued and escalating killing and expulsion of West Bank Palestinians. The 2014 annexations, which represented the largest land grab for over 30 years and which appeared to institute a new era of state policy, have been followed up in subsequent years with more land claims and settlement-building.

Israeli military and settler raids and massacres in the West Bank, which had already killed 248 in 2023 before the حَمَاس (Hamas) October 7 offensive had taken place, accelerated after the attack, with forced expulsions of Palestinians (including Bedouin Arabs), and harassment, raids, kidnappings, and torture of Palestinians by a military armed with rifles, tanks, and drones. This violence has been opposed by armed resistance groups, who defend refugee camps from military raids with strategies including the use of improvised explosives.

Support Palestinian resistance by buying an e-sim for distribution in Gaza; donating to help two Gazans receive medical care; or donating to help a family leave Gaza.

[1] 918 dunums were devoted to turnips according to the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) report for 2009; the 2008 PCBS report attributes 253 dunums of turnip cultivation to Al-Khalil ("Hebron") for 2006–7.

[2] Today, Gush Etzion is connected to Al-Quds by an underground road that runs beneath the Palestinian Christian town of بَيتْ جَالَا (Bayt Jala).

Ingredients:

Makes 2 1-liter mason jars.

500g (4 medium) turnips

1 beetroot

1 medium green chili pepper (فلفل حار خضرة), halved

2 small cloves garlic, peeled

1 liter (4 cups) distilled or filtered water

25g coarse sea salt (or substitute an equivalent weight of any salt without iodine)

Some brining recipes for lifit call for the addition of a spoonful of sugar. This will increase the activity of lactic-acid-producing bacteria at the beginning of the fermentation, producing a quicker fermentation and a different, sourer flavor profile.

Instructions:

1. Clean two large mason jars thoroughly in hot water (there is no need to sterilize them).

2. Scrub vegetables thoroughly. Cut the top (root) and bottom off of each turnip. Cut each turnip in half (from root end to bottom), and then in 1 cm (1/2") slices (perpendicular to the last cut). Prepare the beetroot the same way.

If you need your pickles to be finished sooner, cut the turnips into thinner slices, or into thick (1/2") baton shapes; these will need to be fermented for about a week.

3. Arrange turnip and beet slices so that they lie flat in your jars. Add garlic and peppers.

4. Whisk salt into water until dissolved and pour over the turnips until they are fully submerged. Seal with the jar's lid and leave in a cool place, or the refrigerator, for 20–24 days.

The amount of brine that you will need to cover the top of the vegetables will depend on the shape of your jar. If you add more water, make sure that you add more salt in the same ratio.

289 notes

·

View notes

Text

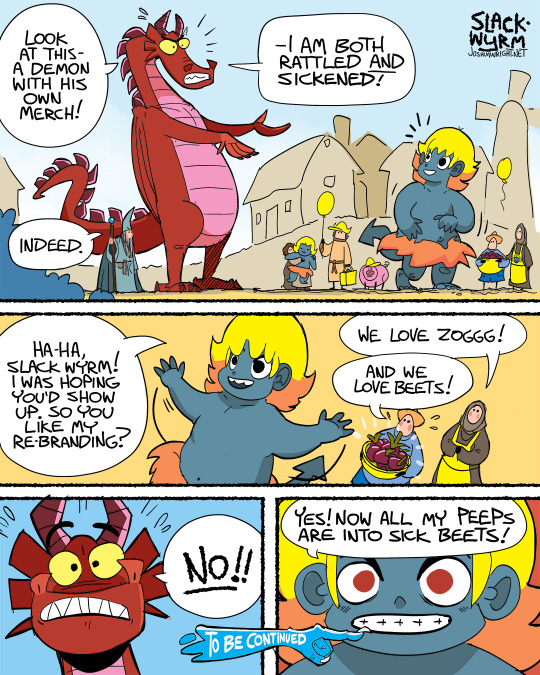

Slack Wyrm #1188

197 notes

·

View notes

Text

🦢 BEET SOUP RECIPE ALERT 🦢

This recipe is for a roasted beet, squash, pepper soup with a lemony yogurt sauce topping!

Its my favorite new dinner I've been eating all December + I wanted to make the recipe available for purchase cause I have a kitty vet bill to take care of today! I've never had beet soup before I put together this one but honestly it's a super simple straight forward meal to have in your back pocket and I'm very proud of it!!!

HOW TO PURCHASE:

1. Send $5 to @allmoneynshit on venmo with the words "beet soup" in the notes

2. Send an email to [email protected] titled "BEETS PLEASE" and I'll respond to the email with the digital recipe pdf booklet ✨

*~This recipe is digital release only~*

thank u and enjoy!

191 notes

·

View notes

Photo

she got them big beets

198 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Honey" Miso Ginger Dressing (Vegan)

#vegan#salad dressing#diy#vegan honey#miso#ginger#onion#garlic#vinegar#soy sauce#sesame oil#black pepper#sea salt#lunch#dinner#salad#lettuce#beets#cabbage#carrots#cucumber#avocado#sunflower seeds#sprouts#eat the rainbow

101 notes

·

View notes

Text

Creamy Roasted Beet Pasta Sauce

#food#recipe#dinner#pasta#beets#cheese#ricotta#goat cheese#onions#garlic#lemon#vegetarian#gluten free

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Two rows of Chioggia beets, where half of them are this size. I'm going to enjoy harvesting these.

#that's a 2.3 kg Chioggia beet right there#chioggia beets#orchard garden#beets#gardeners on tumblr#grow your own food#gardenblr#edible gardening#garden#gardenblog#gardening#gardencore

114 notes

·

View notes

Text

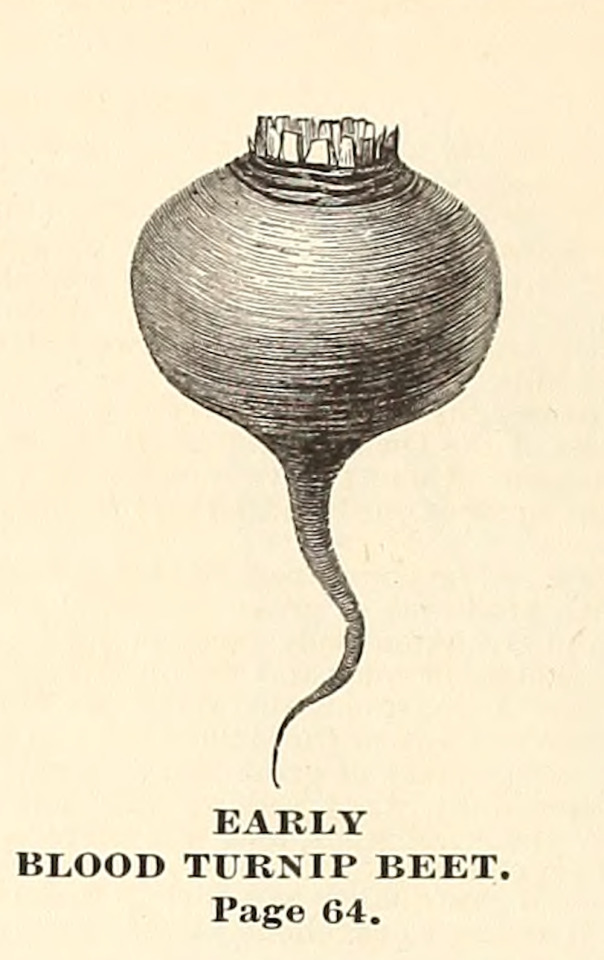

Blood turnip beet. B.K. Bliss and Son's illustrated spring catalogue. 1871.

Internet Archive

100 notes

·

View notes

Text

Vegan Autumn Rolls With Pumpkin

#vietnamese spring rolls#summer rolls#lunch#savoury#food#recipe#recipes#pumpkin#tofu#hokkaido#rice noodles#pear#avocado#pears#beetroot#beets#beet#tahini#radicchio#tasty#vegan#veganism#vegetarian#glutenfree#gluten free

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

Shaved Root Salad with Grapefruit Thyme Dressing

#recipes#winter recipes#spring recipes#salads#root vegetables#grapefruit#carrots#beets#endives#radishes

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beet, zucchini, and carrot goat cheese rose tart

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Slack Wyrm #1189

http://linktr.ee/joshhamwright

204 notes

·

View notes

Text

drawing some ingredients for a borscht recipe

PSA while i’m writing and assembling this cookbook, which i suspect will take a while, i’m posting recipes twice a month over on Patreon!

67 notes

·

View notes

Text

Harvesting beetroot 👀🤷🏾♀️

25 notes

·

View notes