#bertillon measurements

Text

3 notes

·

View notes

Note

the searchizer 🤨

🤨

1 note

·

View note

Text

[“Fingerprinting was pioneered on women arrested for prostitution for a few reasons. First, there were many of them, so the police had a large pool upon which to experiment. Additionally, previous anthropometric techniques of tracking criminals (what were known as Bertillon measurements) had been developed on men, and they didn’t work well on women. Most importantly, however, women who were repeatedly arrested for prostitution were considered naturally criminal—like “perverts,” or drunks, or vagrants, or “born tireds.” As their deviant bodies supposedly led them to commit crimes, it made sense to track those bodies themselves.

Thus a stunning perversion of justice was accomplished: recidivism became a stand-in for being born bad. Judges began to base sentencing not on the crimes in front of them but on a biologically based assumption of inherent criminality—the “proof” of which was a previous history of arrests. That recidivism might indicate a failure in the system, or that the arrested individual might be experiencing persistent poverty, societal persecution, racism, misogyny, etc. did not seem to occur to the rich, white, straight men who made the system.

This leads to the final reason fingerprinting was pioneered on arrested prostitutes: they were considered fundamentally disposable, and if it turned out that fingerprinting did not work for identification, “the consequences of an error in a prostitution case was not all that dire.”Unless, of course, you were the arrested person. Soon, fingerprinting would be expanded to other disposable classes of feminine people, particularly abortionists and men arrested for homosexuality. Only after it had been thoroughly tested on these groups would fingerprinting be expanded to common procedure.

Fingerprinting put women like Mabel Hampton at a unique disadvantage: unlike men, they couldn’t give a fake name to avoid outstanding warrants or hide previous arrests. Unsurprisingly, the Fingerprint Bureau found that during the 1920s “the problem of the female offender [grew] increasingly difficult.” In the Department of Correction annual report for 1929, they speculated this was caused by “the comparative emancipation of woman, her greater participation in commercial and political affairs and the tendency toward greater sexual freedom.” Or, they acknowledged later in the report, “the figures may merely represent an increased activity on the part of the police.”]

hugh ryan, the women’s house of detention: a queer history of a forgotten prison, 2022

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

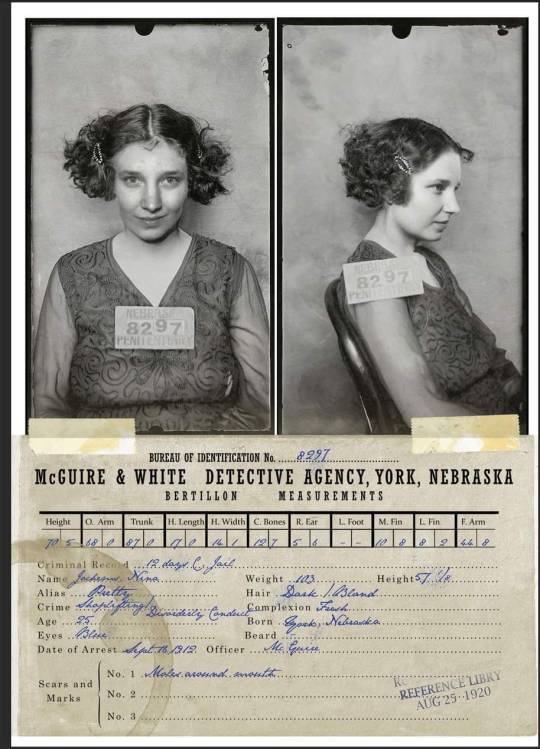

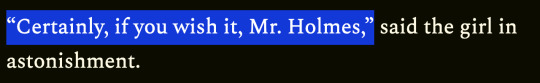

Alphonse Bertillon, a French policeman in the late 1800s, invented the mugshot. Here's his "Bertillon card" for himself.

You can see that it includes a pretty standard front-and-side mugshot, but that’s just one aspect of the Bertillon system. Above his photo are all sorts of measurements and descriptors — of his head, eyes, ears, and hands, along with his hair and beard. These cards were filed using a complex system that allowed police to find criminals with, say, big hands and small noses.

Bertillon believed that, if the police collected enough data about people, they could sort through their collection of cards and, by process of elimination, find the people they were looking for.

Read the whole story here:

{WHF} {Ko-Fi} {Medium}

113 notes

·

View notes

Text

Letters from Watson: the Naval Treaty

Part 3: The Fun Bits

Holmes, your Watson is a DOCTOR, it's not a question of if his cases are more interesting, it's a question of people getting medical care on time!

Not that he appears to be seeing a lot of patients at present - I guess the multitude of bacterial and viral illnesses that become more prevalent during the summer - whether they be typhoid or polio - aren't driving a lot of patients his way this year.

Forbes is not a member of the Yard who already likes or appreciates Holmes: when it comes to the credit for the case I wonder if Watson tagging along ever clues the police in that it will (eventually) be a case where the credit does go to Holmes.

(Watson had published only the two novels by 1889 so if the police ever associated his presence with not getting credit, they would not have known to do so now.)

If Lord Holdhurst is modeled after a premier (prime minister) who had actually been in office between 1889 and 1893, our choices are either William Ewart Gladstone (In office 1892-1894) or Robert Gascoyne-Cecil (1886-1892) again. Gascoyne-Cecil's party is listed as conservative, so it's probably him, if anything, though that uh... fucks up our timeline if he's not prime minister YET.

If "Holdhurst" and "Bellinger" (from Second Stain) are both intended to be Gascone-Cecil and Watson's dates in this story are right, his government had TWO document disappearances within the space of about three months. Within six months, if we take fall or very late summer of 1889 to be the date for The Second Stain (Which is contrary to what Watson has said in this story.)

If Holdhurst is intended to be somebody else who is likely to be in the running for prime minister eventually, then Holmes is paying atypical attention to party politics (possibly due to his brother?) and I have no leads on who Holdhurst is an expy for.

The Bertillon system of measurements was a record not only of a convicted criminal's photograph, but head and hand measurements, so they could more easily be identified later. His system's most famous failure would be in the Dreyfus Affair in 1894

Once again, Holmes enlists the help of the only woman connected with the case. And gets the person currently in the most danger away from the scene.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

I want to talk about Bertillon!!!

As a forensics major, I have been told a lot about his system and it's bizarre! If anybody hasn't heard of anthropometry it's so wild.

So basically, Bertillion was a pioneer in the field of forensics and criminalistics and came up with this pseudoscience where he would measure various body parts as a way of individualizing a person. This was all well and good until Will and William West who just happened to have the same measurements.

Anthropometry and the Bertillion system were a precursor to fingerprinting but it was even more subjective. There was no standardization on how to measure, just what was measured. Honestly, it's wild to read about as a forensics person, or well a scientist in general, the lack of real oversight there was in the beginning.

Though with all the shit I just gave Alphose Bertillion, he did come up with one of the first popular criminal identification systems outside of simple profiling when cities were on the rise, and so was crime. So kudos to his effort and legacy I guess.

18 notes

·

View notes

Text

Letters From Watson Liveblog - May 7

The Naval Treaty, Part 3 of 4

You know, I assumed that Holmes' odd digression into the providence of roses in the last letter served some purpose for solving the mystery, but here he's alone with Watson, waxing metaphoric about the future of England, so maybe he's just been in a philosophical mood recently when Watson came to him.

I find it funny that Holmes refers to it as his case, as if it wasn't Watson who brought the problem to him in the first place, and the client wasn't Watson's old school friend/victim.

Also, I now know that "asperity" means "harshness of tone or manner," which strikes me as a bit more aggressive than how Holmes usually talks. He also jumps to the conclusion that Watson's leaving to go back to his job, which makes me think he probably felt slighted that Watson might bring an interesting case to him and then leave before it's done. They haven't seen each other in a while after all, so he was likely expecting a full, classic adventure and not just a tease of one. Which he gets of course.

See, it's stuff like this that makes Holmes such a good detective. Not just that he considers all possibilities, but that he doesn't let things like someone being a noble or a statesman get in the way of thinking of them as the criminal.

Another in a long line of Watson describing inspectors by comparing them to animals. I had assumed he just did this for Lestrade, but I guess he does it for just any inspector, for some reason.

This exchange took quite a nice turn. You'd think an inspector who has a negative, pre-formed opinion about Holmes, on being called "young and inexperienced" by him, would get very upset. So kudos to Forbes for being surprisingly understanding.

Did Scotland Yard have female officers back then? Or is this referring more to something like a female servant than anything else?

I'm not sure you can really tell how noble someone is from looks alone, but if Watson wants to go off about his "thoughtful face" and "curling hair prematurely tinged with gray" then who am I to stop him.

Holmes subtly suggesting that Phelps is the real culprit, not because he genuinely believes it, but to see how Lord Holdhurst reacts.

And he reacted correctly. So that's Lord Holdhurst off the suspect list. It's good he won't make any qualms about the culprit possibly being his nephew.

Looking into the Bertillon system, it seems to be a precursor system to fingerprinting in order to identify criminals that involved more physical measurements. Its creator, Alphonse Bertillon, also created the mugshot in conjunction with the Bertillon system.

He apparently also gave key evidence as a handwriting expert (despite not being one) in the Dreyfus affair, which condemned a Jewish French military official to false imprisonment for treason. His testimony was later found to have little scientific value, which later (despite a lot of military cover-up and anti-semitism) led to Dreyfus being exonerated. There's also a lot more to the Dreyfus affair, and it all sounds pretty terrible.

Anywho, all that happened after The Naval Treaty was published, so I guess, as of the time of this story, Holmes doesn't have any particular reason to not admire Bertillon and this new criminal identification system. He soon will though.

Good on Phelps for taking all this in stride. He lost an important document, probably lost his job, got a brain-fever for nine weeks, had to ask one of his schoolyard bullies for help, and was the near victim of a nighttime robbery. "Misfortunes never come single" indeed.

Ms. Harrison agrees to do this pretty quickly, but I guess she has no reason not to. Though Holmes never said anything about hiding the fact he asked her to do this, so good on her for realizing it and coming up with an excuse on the fly.

Part 1 - Part 2 - Part 3 - Part 4

#letters from watson#the naval treaty#sherlock holmes#john h watson#percy phelps#joseph harrison#annie harrison#lord holdhurst#mr forbes#arthur conan doyle#liveblogging sherlock holmes

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alphonse Bertillon (French: [bɛʁtijɔ̃]; 22 April 1853 – 13 February 1914) was a French police officer and biometrics researcher who applied the anthropological technique of anthropometry to law enforcement creating an identification system based on physical measurements. Anthropometry was the first scientific system used by police to identify criminals. Before that time, criminals could only be identified by name or photograph. The method was eventually supplanted by fingerprinting.[1] (Wikipedia)

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

WHOO!

I get to teach Forensic Sciences again next semester! With a prof I really like and have previously TA’ed for! It’s a super fun course - Intro to Criminalistics - so it’s a little bit of everything. Prints, bones, blood, DNA, drugs, mapping, and more. She’s also researching Forensic Anth, so we can dork out about bones.

AND I’m teaching Crim Theory, too, which is a designated writing-intensive course. I have not worked with the prof for this course, but I hear she’s awesome. Not only do I get to dive into the history of Criminology again, but go absolutely ham on essay-writing technique and tips. (YOU WILL LEARN TO STACK AN ARGUMENT. I can’t guarantee you will learn to love APA, but you will come to grips with it and develop a personalized checklist with samples of in-text citations and title page contents, in order.)

Lesson 1: Who Are You? (Who who? Who who?)

[Text ID: An antique parody of a double mug shot, in sepia tones. A 23-month-old infant with curly light hair sits in a plain wooden high chair, a winsome expression on his face. He is dressed in a typical child’s white frock of the period with a frilled collar, sleeves and skirts. The first panel is in profile, with the child facing right. The second panel is face-on. The inscription reads: François Bertillon, âgé de 23 mois. 17 - oct - 93.]

This infantile mug shot, now in the MOMA collection, is commonly known as: “François Bertillon, 23 months (Baby, Gluttony, Nibbling All the Pears from a Basket)”

Alphonse Bertillon, a French police officer from the late 1800s, sought to revolutionize criminal identification by statistical means. He developed a system, which he called Bertillonage, of body measurements - anthropometry - that could be tabulated and compared with others, under the assumption that no two people would share the exact same measurements.

Now, this idea was an offshoot of biological determinism, a theory that the body itself predicted behaviour and the state of the mind. Biological determinism was actually a revolution in its day: it represented a split from the previous belief that aberrant behaviour and physical infirmity were proof of demonic influence and a directly-involved God. However, biological determinism, itself an offshoot of Platonic essentialism, led to such notions as Lombroso’s “atavistic”-bodied criminal with a hulking body, a lowered brow and a “stupid stare”, as well as pseudo-science parlour fun like phrenology. Not to mention the blatant eugenicism and superior-more-developed-race blather that still persists in many branches of social sciences.

But two hundred and some years into the European Enlightenment, empirical science was moving slowly towards the acceptance of provable, testable hypotheses based in reason and repetition. So Bertillon reasoned that, if you went about the task scientifically, with enough detail, you ought to be able to prove that no two people had the same bodies, and could therefore be told apart. (And just maybe prove that you could tell a criminal from looking at them.)

But no. The collection of Bertillonage data was incredibly painstaking. Subjects had to have a long series of measurements taken, in the exact same postures, using the same equipment. Then, the subjects were required to have photographs taken, from specific angles: the first mug shots. Bertillion spent years perfecting his photographic system. The above photos of his little nephew François are just one example of Bertillon bringing his whole family into the process - an excuse to combine his work with his hobby of photography and his love of his close-knit family.

(Note the implication here: “My family is the control group, the ideal specimens. Normal people look and behave like us.” When thinking about data, always ask yourself: who’s taking the photographs? Who’s collecting the samples, and from where, and how, and why those samples in particular?)

Bertillonage didn’t take off. People have too many similarities as well as differences, and the human error involved in the measurements and photography was too great. But he did create a stunning longitudinal study of his family and friends over a couple of decades, as well as of local criminals. Here’s François a few years later. Can you see details that persist through out his aging? How would you describe them?

You can see here some of the prescribed measurements in the Bertillonage system - and they didn’t have spreadsheets to look up and compare cases!

Bertillon’s underlying idea had merit. No two people are exactly alike. Even identical twins develop epigenetic differences over time. Fingerprints form in the womb, with randomized development due to the uterine environment. We can only measure these things with technical tools - low tech like magnifying glasses, high tech like digitized pattern recognition and molecular amplification. But we’ll get to that later.

Before you leave! Your homework this week is to write a description of yourself that is detailed enough that it would help investigators identify your remains. Under 500 words please. Point form is fine. Post to Canvas by midnight Sunday.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thoughts on L'Evasion d'Arsène Lupin part 2

se jouer du présidente - from context I assumed it meant "to own the room" or "to steal the show" at first, but as I read on and realized "president" is more in line with "judge" in this context, I think it's more "to toy with the judge."

Lupin is a magician, medical doctor, Jiu-Jitsu expert, and cyclist. Perhaps his real name is van Helsing? In all seriousness, this sounds like Lupin isn't one guy but a gang of experts.

Et il entra dans le détail des vols, escroqueries et faux reprochés à Lupin

thefts, scams, and false reproaches? Forgeries, I assume? It would be funnier if it was something extremely minor, but I think forgeries makes the most sense.

"Or" being used to mean "but" keeps throwing me off. False cognates are the worst.

Un silence. Et soudain, dans ce silence un éclat de rire retentit, mais un rire joyeux, heureux, le rire d’un enfant pris de fou rire, et qui ne peut pas s’empêcher de rire. Nettement, réellement, Ganimard sentit ses cheveux se hérisser sur le cuir soulevé de son crâne. Ce rire, ce rire infernal qu’il connaissait si bien !…

You know, I would really like to hear Lupin's laugh. I bet it's fantastic.

un blanc-bec - a white beak? from context, I'd guess someone who is inexperienced

« Du moment qu’Arsène Lupin crie sur les toits qu’il s’évadera, c’est qu’il a des raisons qui l’obligent à le crier. »

Lupin makes a good point. In the last story, Lupin explained that he'd announced his intention to commit a burglary because he needed the reaction to the announcement in order to pull it off. He used the same technique with his escape.

I admit, Leblanc had me fooled at first. When they brought the prisoner in, I assumed Lupin had pulled off a switch somehow, and that being moved from one cell to another after his first escape had been part of the plan. But, once we found out Baudru had been in Lupin's cell for two months without complaining I became suspicious. It strained credulity. The only person who wouldn't complain about being in Lupin's cell is Lupin himself.

Le système Bertillon - Alphonse Bertillon was a French policeman who categorized criminals by a number of measurements: head length, head breadth, length of middle finger, length of the left foot, and length of the cubit (middle finger to elbow). The idea being that while some measurements would be the same for different people, it was unlikely all the ones he took would be. He also standardized the mug shot. I suppose it worked better than nothing.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

French researcher Alphonse Bertillon demonstrates how to measure a human skull in Paris, France in 1894. Bertillon was a criminologist who first developed a system for measuring physical body parts - particularly of the head and face - to work out if someone might be a criminal.

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Top, screen capture from See You in Hell, My Darling, directed by Nikos Nikolaidis, 1999. Via. Bottom, Tracey Emin, Is This a Joke, 2009, embroidered blanket, 224 x 200 x 12 cm. Via.

--

Fingerprinting was pioneered on women arrested for prostitution for a few reasons. First, there were many of them, so the police had a large pool upon which to experiment. Additionally, previous anthropometric techniques of tracking criminals (what were known as Bertillon measurements) had been developed on men, and they didn’t work well on women. Most importantly, however, women who were repeatedly arrested for prostitution were considered naturally criminal—like “perverts,” or drunks, or vagrants, or “born tireds.” As their deviant bodies supposedly led them to commit crimes, it made sense to track those bodies themselves.

Thus a stunning perversion of justice was accomplished: recidivism became a stand-in for being born bad. Judges began to base sentencing not on the crimes in front of them but on a biologically based assumption of inherent criminality—the “proof” of which was a previous history of arrests. That recidivism might indicate a failure in the system, or that the arrested individual might be experiencing persistent poverty, societal persecution, racism, misogyny, etc. did not seem to occur to the rich, white, straight men who made the system.

This leads to the final reason fingerprinting was pioneered on arrested prostitutes: they were considered fundamentally disposable, and if it turned out that fingerprinting did not work for identification, “the consequences of an error in a prostitution case was not all that dire.”Unless, of course, you were the arrested person. Soon, fingerprinting would be expanded to other disposable classes of feminine people, particularly abortionists and men arrested for homosexuality. Only after it had been thoroughly tested on these groups would fingerprinting be expanded to common procedure.

Fingerprinting put women like Mabel Hampton at a unique disadvantage: unlike men, they couldn’t give a fake name to avoid outstanding warrants or hide previous arrests. Unsurprisingly, the Fingerprint Bureau found that during the 1920s “the problem of the female offender [grew] increasingly difficult.” In the Department of Correction annual report for 1929, they speculated this was caused by “the comparative emancipation of woman, her greater participation in commercial and political affairs and the tendency toward greater sexual freedom.” Or, they acknowledged later in the report, “the figures may merely represent an increased activity on the part of the police.”

Hugh Ryan, from The women’s house of detention: a queer history of a forgotten prison, 2022. Via.

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

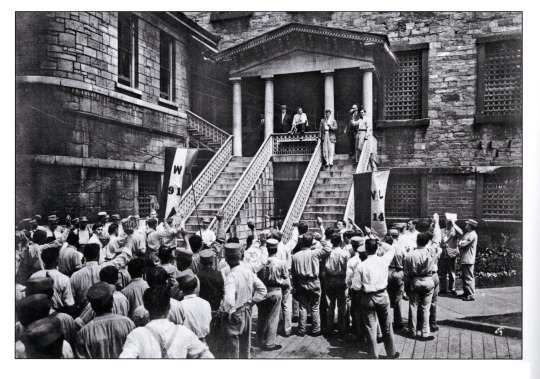

"[Thomas Mott] Osborne commenced the work of reforming Auburn Prison along new penological lines two months after his release from that prison. In early December 1913, he prevailed upon Warden Rattigan and Superintendent John Riley to allow him to organize prisoner self-government at Auburn. Over a three-week period, beginning in late December 1913, Osborne met regularly with the Auburn prisoners and oversaw the creation of what came to be known as the Mutual Welfare League (MWL). He began by addressing the Auburn prisoners en masse in the chapel in late December 1913, and informing them of his conversation with prisoner Jack Murphy, and the plans for the new organization. Elections were to proceed with the purpose of electing a body of delegates that would act as a “constitutional convention” entrusted with the task of drawing up a constitution and rules for the prisoner organization. In effect, Osborne was recreating the political “state” of the George Junior Republic in a state prison.

When election day rolled around on December 26, 1913, 1,285 of Auburn’s 1,382 prisoners voted in their workshops for delegates. Each prisoner wrote the name of a prisoner from his work company on a specially prepared voting form and dropped it into a sealed box that was carried from shop to shop by the prison clerks. The votes were then counted in the warden’s office by the warden’s secretary, the prison’s Bertillon clerk, and two prisoners. The names of the forty-nine delegates elected to frame the prisoners constitution were announced that evening. Two days later, the forty-nine delegates of the constitutional convention met in the chapel to debate the form and purpose of their new organization. Warden Rattigan called the meeting to order, informed the prisoners that they would be allowed to meet “in secret,” and then departed with the guards. This meeting of prisoners without guard supervision was unprecedented. Osborne stayed with the delegates and was elected Chairman of the meeting, whereupon he proceeded to set out the three questions to be addressed by the constitutional convention of prisoners: He asked, who should be a member of the league? What should the organization do? How should executive officers be selected from among the delegates? The delegates agreed that membership of the organization should be extended to all prisoners other than those undergoing punishment in the isolation cells. Prisoners were to join by taking a pledge. Following this discussion, Osborne selected from among the forty-nine delegates twelve prisoners to draw up the constitution and bylaws of the society.

(Osborne – and his biographers – maintained that the impetus for the reforms came from the prisoners themselves. In Within Prison Walls, as well in his public lectures and other writings, Osborne emphasized the extent to which the idea came from the prisoners (one prisoner in particular, Jack Murphy), and represented his own role as one of simple facilitation of the prisoners’ will to organize. Such a representation indicates the desire of Osborne (and other progressive penologists) to indicate to the public that prisoners were capable of generating and supporting democratic institutions, which, for Osborne, was the measure of a prisoner’s potential fitness for citizenship. However, as the pages that follow establish, Osborne took a far more active role in organizing the league (writing its constitution and guiding its operation) than he ever acknowledged.)

The forty-nine prisoner delegates concluded this first meeting by drafting a letter to the state’s Superintendent of Prisons, John B. Riley, in which they hailed him as the visionary and architect of the tentative reforms at Auburn. They congratulated Riley for having personally “inspired among the officers and prisoners of [Auburn Prison] a new and kindly spirit of physical, moral and humanitarian progressiveness.” Continuing in a register designed to assure Riley of his place in history, the prisoners wrote that his support “warrants the hope of more considerate management and supervision of the whole personnel of the said Prison than that which has obtained in all the previous history of prison conduct.” As though to hold Riley to his word – or warranty, as the prisoners’ language infers – Riley was told that the prisoners would be sending him an engrossed copy of their resolutions “as a souvenir to recall the inauguration of a more promising future for those who for so many years have been considered outside the pale of human kinship.” The next day, the prisoners sent this letter and the engrossed copy of their first resolution to the Superintendent in Albany.

The letter’s lofty language, its authors’ celebration of Riley as an enlightened humanitarian, and the appeal to Riley’s sense of his own historical importance were rhetorical techniques that the league organizers would repeatedly deploy in addressing officials. As we have seen, since at least 1899, prisoners at Auburn, Sing Sing, and other institutions had appropriated the officials’ language of progress and humanitarianism as a technique in affirming certain prison practices and in requesting new reforms. The authors of the letter to Superintendent Riley knew very well that he had simply rubber-stamped a proposal that had originated with someone else, and for which he could take little credit. Nonetheless, the experiment of setting up a prisoners’ league could not proceed without his consent, and was more likely to succeed in the long-term if it received the active support of Riley and the carceral bureaucracy. Consequently, in this, and in many subsequent letters and publications, the prisoners attempted to convince Riley – and other officials – of the historical significance of the reform and of the prestige it would accrue to the administration. In an era in which state governments strove to be at the forefront of “humanitarian reform,” rhetoric such as this remained one of the critical weapons in the rather limited arsenal available to prisoners in the struggle to improve their lot. Unlike the riot and the strike, this strategy was not likely to provoke bloody repression and it presented prisoners not as violent, dangerous convicts who needed to be screwed down, but as reasoning human beings who would cooperate with the prison regime if treated as such. Of course, unlike the riot or strike, the polite letters of prisoners could be easily ignored. However, for a time, at least, the prisoners met with some success: Soon thereafter, Superintendent Riley began boasting to the press of “his” reforms at Auburn.

From the beginning, the prisoner delegates set out to record their organizing efforts: At their first meeting, they immediately appointed the warden’s stenographer, prisoner S. L. Richards, as official clerk of the organization. Over the following months, Richards proceeded to generate a stack of minutes and reports that meticulously chronicled the rise of the inmate organization. These records provide tremendous insight into the chronology of events, the points of conflict among the prisoner delegates, and Osborne’s role in fostering the organization. On a deeper level, they also afford a rare glimpse into the workings of authority in the prison, the relations between guards and prisoners, and the day-to-day concerns of prisoners in the 1910s. As with any archival material, it should be noted, the specific conditions under which these invaluable records were created must be borne in mind. The minutes are incomplete and they are silent on certain critical issues that arose in the prisoners’ meetings. Secretary Richards was extremely cautious in his reporting of certain discussions that took place among the prisoners. For example, he frequently omitted lengthy discussions about socialist organizers in the prison (to whom the league leadership were opposed), disciplinary arrangements, and relations with the authorities. Whether through his own volition or because of instructions from the delegates, it is clear that conversations on these and other strategic matters were selectively and carefully reported.

This incompleteness serves to negatively document an important aspect of incarceration in the 1910s: Few prisoners wanted their opinions on guards and problems such as theft and violence in the prison to be recorded in writing, despite the assurances of Warden Rattigan that their meetings would proceed in “secret.” As Richards and his fellow organizers appear to have been aware, the new “openness” of prison authorities and the opportunity to organize without official surveillance brought with it new dangers: Putting details of guard brutality, official corruption, and prisoner rule-breaking in writing could lead to retribution, on the part of the authorities, and possibly even bring an end to reforms. In fact, Richards’ cautiousness was vindicated two years later when the “confidential agent” of the Superintendent of Prisons surreptitiously removed papers from Sing Sing with the intention of finding incriminating evidence about the Sing Sing MWL. Following the agent’s botched attempt, officers of the Sing Sing league destroyed most of the league’s disciplinary records.

Two days after the forty-nine prisoner legislators had first met to discuss the framing of a constitution, Osborne’s handpicked “Committee of Twelve” convened in the warden’s office to discuss the creation of a prisoner league. This was the first of five intensive meetings that took place over the first week of the New Year, 1914. By the end of that week, the Committee had hammered out a blueprint for the organization, disciplinary procedures, and new privileges for Auburn prisoners. Once again, the prisoner delegates were allowed to meet without the warden and the guards in attendance and Osborne convened as Chair. The twelve delegates discussed the transfer of certain police powers from the guards to prisoners, the establishment of freedom of the yard (by which prisoners would be allowed an hour or two a day to socialize and exercise in the prison yard), and the election of delegates to the league’s governing body. They also discussed the procedures for electing representatives to a prisoner legislature and compared different electoral systems. The committee heard one delegate, Shea, report on the Commission system of voting used in Iowa and other states, and after some discussion, they agreed to adopt this electoral method as the most democratic means of setting up their organization. Another election would be held in which prisoners of every work company would vote for company representatives (the number to be determined according to the size of each company), who would then convene as a general commission or governing body for the league. Toward the end of this meeting, the first draft of a constitution and bylaws for the still unnamed prisoner organization was presented and discussed. It is unclear who authored this draft, but it is likely that Osborne influenced its contents, as it conformed to many of his ideas about the prisoner league. The draft provided for the mode of election (commission system), and the appointment of a secretary and a sergeant-at-arms for the organization. With regard to the league’s bylaws, this first draft stated that the organization’s rules were to be the rules laid down by the New York State Prison Department for the administration of Auburn Prison. In other words, the league would adopt the official prison rules as its own.

As the meeting progressed, the question of rules, and the larger question of which they were a part – police powers in the prison – quickly became the central issue of contention among the delegates. These questions arose as the Committee of Twelve began to discuss the way in which they would organize one of the most sought-after privileges: freedom-of-the-yard. This privilege was keenly pursued for the reason that it would alleviate one of the most repressive and despised practices of incarceration: the sixteen and one-half hours every prisoner spent in his cell each day between the hours of 3 p.m. and 7:30 a.m. Although the Committee took it for granted that procuring freedom of the yard for all prisoners was of primary importance, the question of who would supervise the prisoners during yard recreation became the subject of protracted debate among Committee members. The crux of the question related to the disciplinary role of guards and the assumption of limited police powers by prisoners. Some delegates argued that the presence of guards during yard recreation would be necessary for the protection of the prisoners. They affirmed the position of delegate Shea, who had argued that every institution – even a “peanut stand,” as he put it – needed a system of authority. “I have seen the time, and it was a bad time in prisons,” warned delegate Cameron, “when there was (sic) no officers in the hall.” Delegates worried that the absence of guards would lead to abuse and violence among prisoners; in the 1910s, guards might assault prisoners, but in the interest of maintaining order, they generally ensured that prisoners did not assault each other. (Prison administrations had not yet fully discovered the usefulness of prisoner-on-prisoner violence as a technique of prison government).

Implicit in the delegates’ discussion (and made more explicit in the many debates that were to follow) was the prisoners’ recognition of the fact that freedom of the yard was likely to generate more labor for guards, without increasing their wages. Guards were already working six days per week, on twelve-hour shifts. Whereas only six guards were needed on duty once the prisoners had been locked in their cells for the night or on Sundays, many more would be needed to supervise 1,400 prisoners in the yard. Although elite prison reformers rarely took guards into account in their attempts to reconstruct prison life, prisoners were well aware of the need to win over guard support for reforms, or, at the very least, ensure guards were not actively opposed to the reforms. As delegate Shea had pointed out the day before, it was critical to gain their sympathy, as the guard “is the power down in the shop and the man behind the power of the ‘reprimand’ or the ‘chalking in’. ... Unfortunately (the guards) have us in their power.” Increasing the guards’ labor would probably alienate them at the most sensitive stage of the league’s development. Shea continued:

I do not want any more privileges if it is (sic) to extend the hours of the keepers. They feel disgruntled enough now and the success of this organization depends upon the good will and support of the keeper. Now we have got to face these things. It is all right for us to say he is not in this thing, and we dont (sic) want to support him, but there he is with that blue coat and that stick. They constitute authority and we have got to work in concert with them because he (sic) is a part of our life and his (sic) attitudes towards anything that is to be done for us must be considered.

Shea went on to argue that the guards were hoping that the reforms would benefit themselves as well as the prisoners and that if the reforms did in fact benefit guards, they would be both invested in having the prisoner organization succeed, and less inclined to report prisoners for breaches of prison rules.

In light of these considerations, a delegate who was one of Osborne’s principal supporters (delegate Barr, a teacher in the school company), suggested that the prisoners devise a method to police themselves during recreation. Each prison company should elect two prisoners to act as sentries, guarding the entrances to alleys and shops, just as prison guards were posted during work hours. Despite initial opposition to Barr’s suggestion, he ultimately prevailed. This was largely because his suggestion met with Osborne’s approval, and, perhaps recognizing the real power relations of the situation, the Committee tended to defer to Osborne’s opinion. It became evident in the subsequent meetings of the Committee of Twelve in the first week of 1914 that Osborne envisioned a new mode of penal discipline whereby the prisoners would take responsibility not only for policing during freedom-of-the-yard, but for much of the daily order in the workshops, mess hall, and marching lines. He viewed prisoner police powers as part of the greater project of fostering what he called “self-discipline” and loyalty among the prisoners. Furthermore, he linked the introduction of exercise and education programs with prisoner police power: Participation in such activities was a privilege or liberty, in Osborne’s view, and such privileges and liberties should only be extended where prisoners undertook to police themselves.

Ultimately, Osborne prevailed upon the delegates not only to set up a system of prisoner supervision during freedom-of-the-yard, but also to vest in the prisoner league the police powers of citation, prosecution, and punishment. In this vein, he insisted to the twelve constitution framers that the prisoner society should set up a disciplinary body to “try” prisoners who had abused newfound liberties such as freedom-of-the-yard. A court adjudicated by prisoners was legitimate, he argued, because when prisoners break the rules, “they have committed an offense not against the warden, but against you.” Meeting with resistance from the delegates, Osborne went on to argue that privileges such as freedom-of-the-yard could be conferred only in return for prisoner responsibility – specifically, collective responsibility for ensuring the rules were not broken.

In attempting to convince the Committee of the advantages of transferring police powers to prisoners, Osborne argued that prisoner police powers would break what he viewed as the perpetual and destructive opposition between guards and prisoners. Osborne’s program in general aimed to break down the oppositional relationships of guards to prisoners, and of criminals to citizens, by making incarceration a cooperative enterprise among all concerned. He reasoned that only when prisoners cooperated with their own reform and citizens cooperated with prisoners by renouncing revenge and supporting penal reconstruction, would prisoners be rehabilitated and crime, controlled. Here, Osborne echoed the thinking of contemporary penological theorists who advocated reconstructing prisons as educational institutions, and treating prisoners as students in need of training in the skills of labor, economy, and democracy. For this purpose, prisons must be clean, safe, and healthy environments that were conducive to education.

(Osborne’s emphasis on cooperation over conflict, and his efforts to dismantle oppositional relations, resonated with that of another leading institutional innovator of the 1910s: Frederick Winslow Taylor. Published in the same year in which Osborne entered Auburn prison, Taylor’s Principles of Scientific Management elaborated organizational techniques aimed at forging cooperation between labor and capital in search of increased surplus. As has been pointed out, Taylor did not so much invent the techniques for which he is famous, as collate and popularize existing practices as a standardized set of managerial techniques. Much as Taylor claimed that his theory of scientific management was at once ethical, politically neutral, and efficient, Osborne maintained that his penology was “neutral” in the sense that it would work for everyone: It would improve conditions for guards as well as prisoners; it would make healthier, more cooperative prisoners; guards would cease to be subject to violence from prisoners; the rate of recidivism would decline, and ultimately, social efficiency would improve. Notably, the work of both Taylor and Osborne appealed to Henry Ford, who made extensive use of both sets of ideas in his “White Palace” auto-assembly plant in Michigan. Neither Taylor nor Osborne’s theorization of worker and prisoner psychology took account of the larger structural relationships that existed between subordinates and superiors; rather, they attempted to adapt behavior – and ultimately bodies and psyches – as a means to improving and supporting the existing system.)

In trying to convince the twelve prisoners of the legislative committee that they should create prisoner police and disciplinary tribunals, Osborne argued that prison relations were analogous to pedagogical relations. He insisted that the relations between guards and prisoners are “exactly as in any school.” He continued, “(t)here is the false view of the teacher and the false view of the scholar. The false view of the teacher is that he must emphasize his authority from above; the false view of the scholar is that as long as he is under tyrannical authority the scholars must band together against the teacher.” The correct view, as Osborne saw it, was one in which there was no need for authority to be exercised from above; rather, prisoners must exercise it upon themselves, in concert with the administration’s wish for order. Osborne held that guards and prisoners wanted the same thing, even if they did not know it: order and rehabilitation. Invoking the new penological principle that prisoners should act and be treated as men, he argued, “You are either going to be ruled by arbitrary power, or else you are going to rule yourself and assist those whom you select.” Then, in a refrain he was to repeat at critical junctures in prisoner discussions about the creation of the league, he asked, “In other words are you going to be held as slaves, or are you going to be treated as men?”

If being treated as men involved spending less time in the cells, the opportunity to organize recreational and sporting activities, and improved food and sanitation, then prisoners wanted to be treated like men: of the benefits of such reforms, they needed no convincing. But they were not so easily persuaded by Osborne’s psychologistic vision of the prison as a cooperative venture between guards and prisoners, and the meeting drew to a close with no resolution on the question of prisoner policing. At their second meeting, held on New Years Day, 1914, Osborne once again presided as chairman and exerted influence on the matter of policing. Again, he linked the liberalization of prison discipline to the prisoners’ ability to conduct themselves in an orderly manner. He insisted, “the rules you make must be subject to the Prison rules. ... The Prison Rules must hold. What we all hope, I presume, is that the prison rules will be generally relieved or put aside just as fast and just as far as you show you can handle yourself.” The question of prisoner disciplinary tribunals arose and, again, the Committee made little headway toward a proposal: The delegates floated two ideas and Osborne, a third. One delegate (Hodson) suggested that the governing body of forty-nine delegates could also preside as a grievance committee to hear cases arising from the breach of rules; another argued for a military-style court to be presided over by a prisoner chairman and in which the prisoner sergeant-at-arms would “prosecute” prisoners thought to have broken the rules. Osborne rejected the latter proposal outright and offered a modified version of the former: Rather than have the governing body act as a grievance committee, the governing body should elect five of its members to constitute a grievance committee.

The Committee of Twelve did not resolve the matter of police power that day, but resumed their discussion of this critical aspect of prison life the next day. Secretary Richards did not report much of this discussion. In those parts of the discussion that were reported, the prisoners argued at some length about which prisoners were to be authorized to report prisoners to the grievance committee for transgressions of the rules. The critical questions were: If prisoners were to assume responsibility for many aspects of discipline, which prisoners were to exercise police power, how would they be appointed, and to whom would they report incidents of rulebreaking? Those prisoners who were familiar with the prisoner police practices of Elmira Reformatory, where the warden appointed prisoner–guards who then became the warden’s informants and enforcers, were particularly leery of conferring police powers on fellow prisoners. Prisoner police, they argued, acted as rats for the administration. In floating an alternative means of policing, delegate Williams of the Idle Company, prisoners in which were either unable to work or had been punitively prohibited from working, suggested that the league adopt a jury system of policing, in which every prisoner would be eligible for police duty and would be appointed by random selection of his name from a membership list. These prisoner officers would have police power over the entire prison population. But delegate Barr of the School Company (who was one of Osborne’s principal supporters), argued vigorously that such democratic methods would lead to “weak-minded” prisoners being placed in positions of authority over the rest. Other delegates insisted that whoever the prisoner officers were, their police powers should extend only to those men in their own work company, and they opposed Williams’ jury system on the basis that prisoners from one company would exercise authority over prisoners from another.

In the course of this argument over prisoner policing, the implicit tensions in – and limits of – the delegates’ embrace of egalitarian principles became obvious: Any system of policing that conferred upon men from one company authority over the members of another was likely to upset the unspoken hierarchy between companies. ....some companies had higher status than others. The weave shop was considered low status, as the labor was thought to be that of women, and consequently inappropriate for men. More than simple sexist prejudice was at work in the prisoners’ low estimation of the weave shop: Prisoners commonly believed that whereas the print shop, the state shop, and certain of the industrial shops would equip them with skills that would make them employable outside the prison, the weave shop equipped prisoners with skills in what had become a women’s industry on the outside; hence, such skills would be useless in the search for gainful employment upon release. Given the rigid segmentation of the free workforce along the lines of sex, the prisoners’ resistance to working in the weave shop was based on an accurate estimation of their chances of employment on the outside. (Although the labor of the kitchen shop was also the kind of labor typically done by women, the work conditions, better meals, and sociable atmosphere made that company popular among the prisoners). Under the jury system of policing, the prisoners of Williams’ lowly Idle Company or the feminized weave shop might exercise authority over the more privileged prisoners of the print shop or the state shop.

As the twelve delegates failed to resolve this critical question of policing, discussion stretched into a third day. Finally, Osborne raised an objection that apparently laid to rest Williams’ egalitarian jury method of policing: Under the jury system, black prisoners (whom Osborne described as “objectionable men” in the context of their assumption of police powers) could conceivably exercise authority over white prisoners. Osborne’s invocation of the specter of black American prisoners exercising authority over white Americans was his final effort to convince the all-white delegates that Williams’ jury system would overturn the hierarchy among prisoners. Whether persuaded by his comment, or by his ability to effectively veto any developments with which he did not agree, the Committee resolved that the elected company delegates would be given police powers only over the members of their companies. (As black prisoners were concentrated in the idle and unskilled companies, this meant that the vast majority of white prisoners, who were in other companies, would not be subject to their jurisdiction). In this important respect, the prisoner system of authority recognized the existing hierarchies of race and labor among prisoners, and further entrenched them.

Five days after convening their first meeting, the Committee of Twelve had finally generated a proposal for a system of prisoner policing. They had also discussed the question of prisoner adjudication of grievances at length. Building on Osborne’s plan to set up a grievance committee consisting of five delegates, the Committee of Twelve resolved after a lengthy, and largely unrecorded, discussion that there would be eight grievance committees made up of five delegates each, and that these would be put on a revolving schedule to hear both prisoner grievances and reports from the police-delegates of rule-breaking in their companies. The Committee further provided that the prison administration would deal with more serious cases – though the delegates had not yet established the criteria by which an offense would be considered serious.

Finally, on January 4, the twelve prisoner legislators convened one last time in the warden’s office. In the presence of a journalist whom Osborne had invited to the meeting, Osborne read the members the various proposals they had drafted as part of a constitution in the course of the week. The legislators had one hour to consider and vote on the draft before they were scheduled to report back to rest of the forty-nine delegates of the constitutional convention, who were waiting for the Committee in the chapel. Many of the articles of this original draft became part of the final “Constitution and By-laws” of the Auburn league; and later, a number of other prisoner leagues around the United States adapted this statement of principles to their own institutions. The first article provided that the society’s motto would be, “DO GOOD: MAKE GOOD,” and the second announced that, “The object of the League shall be to promote in every way the ture (sic) interests and welfare of the men confined in prison. By gaining for them the largest practical measure of freedom within the walls to the end that by the proper exercise of freedom within the walls within restrictions that they may exercise worthily the larger freedom of the outside world.” This early draft also established the commission system of government, an executive committee (to be elected by the governing body), biannual elections, and the revolving, five-member grievance committees. Despite continued dissent from Williams and the Idle Company, the draft constitution provided that delegates were to have police authority only over their companies, and delegates would elect a prisoner sergeant-at-arms.

Under pressure of time, the Committee hurriedly considered the draft and made some minor alterations. The delegates’ discussion of the draft constitution suggests that the constitution and bylaws were designed both to establish certain new practices and to render them legitimate, not only in the eyes of prisoners but in the eyes of the warden, the Superintendent of State Prisons, the guards, the press, and the voting public. Aware of the presence of a journalist in the room, Osborne warned the Committee that the use of the term “freedom” in the statement of objectives might “scare (outsiders) to death.” Delegate Shea concurred, remarking that the public would be “afraid that we would be going to hang around their houses at night.” Consequently, the Committee amended the article to read: “OBJECT: The object of the League shall be to promote in every way the ture (sic) interests and welfare of men confined in prison.”

At Osborne’s instigation, the draft constitution also provided that all prisoners elected to office be required to take an oath: Delegates would promise to promote “friendly feeling, good conduct and fair dealing among both officers and men to the end that each man after serving the briefest possible term of imprisonment may go forth with renewed strength and courage to face the world again.” Notably, prisoner delegates were to take the oath in the chapel, before an assembly of all the prisoners. Furthermore, the warden, and not the chaplain, would administer the oath. The warden’s involvement in the proceedings would constitute a show of official support for the league, suggested Osborne, and it would give the delegates more respect in the eyes of the men. Although Osborne did not say so, the administration of the oath was designed not only to establish the legitimacy of the prisoner government in the eyes of prisoners, and to lend it the authority of the administration, but to further imbricate the prison administration in the process of reform. In this vein, Osborne also quietly but firmly pressed the committee to further solidify the support of Superintendent Riley and warden Rattigan by having the league confer honorary (league) membership on them. The delegates agreed with Osborne, and, a few weeks later, of their own accord, they made the principal keeper and the prison doctor honorary members as well. The draft also provided that all Auburn prisoners be eligible for membership in the league, and that they could join by signing a pledge in which they promised to “faithfully ... abide by [the league’s] Rules and By-Laws.”

Having hurriedly debated and passed thirteen resolutions in less than an hour, Osborne, the journalist, and the Committee of Twelve concluded their meeting and set out for the chapel, where the rest of the forty-nine delegates awaited their report. At this gathering of delegates, Osborne again took the floor, and proceeded to explain the Committee’s resolutions. He read the proposed constitution and bylaws to the delegates, and then explained the reasons for establishing an Executive Committee of the league. Osborne told the assembled delegates that the Executive Committee would perform one of the most important functions of the league: It would act as an intermediary between the prisoners and the warden. When prisoners had a grievance about the prison conditions such as poor food or inadequate clothing, rather than organize a strike, Osborne emphasized, they should bring it to the attention of the Executive Committee of the league. The Executive Committee would then bring the problem to the warden’s notice. Osborne noted that this approach would also protect prisoners from gaining reputations among the guards as complainers.

Just as prisoner policing had proven to be the most contentious question among the twelve delegates of the Committee, the forty-nine delegates debated prisoner–guards and prisoner disciplinary tribunals at length. Osborne informed the delegates that freedom-of-the-yard was to be granted on Sunday afternoons: The prison guards would be withdrawn from the yard and put on wall patrol: “The state,” argued Osborne, referring to the prison guards, was duty-bound to “patrol its property, patrol its wall and see that you don’t get away. ... the state will patrol the walls, that is their business, but inside the walls it is up to you.” Each delegate’s police authority as an “assistant sergeant-at-arms” was to extend only over the members of his company, except on occasions when the entire prison population would be mixed in together, such as the athletic competitions planned for July 4, Independence Day. Osborne told the delegates that although most prisoners would not cause trouble in the yard, a few men would be waiting for an opportunity to start a fight. Others would try to dodge the head count at the end of the day, and there would be “attempts at that proposition” of sexual liaison. Osborne implored the delegates to ensure that no fights broke out among the prisoners at recreation: The success of the league, he told them, rode on the conduct of the prisoners in the yard. Osborne then floated the idea that every delegate should wear a badge or insignia to “show his power.” Delegates should not have resort to guns and sticks, he argued; instead, their persuasive power was to flow from their league badges, backed up by “bare knuckles” and the aid of other prisoner officers, if necessary. Osborne concluded his explanation of prisoner police powers by imploring the delegates to cooperate with the prison administration in its crack down on the smuggling and use of opium in the prison.

The forty-nine delegates of the constitutional convention proceeded to debate the proposed system of policing and the rest of the draft constitution. Whether or not the word, “prisoner,” should be part of the league’s official name, or be given constitutional expression in any way, was the subject of extensive debate. The issue was framed as a question of whether the prisoners should define themselves as prisoners or as men. The debate over this question amounted to a problem of tactics in the contradictory struggle of prisoners to win for themselves improved conditions in a total institution. In the course of the discussions over the wording of the constitution, it became apparent that the constitution was a multivalent document intended for many different audiences. On one level, the document was to be made public as a manifesto for prison reform: A member of the press had been present at at least one meeting, and a copy would be forwarded to others. In light of this, secretary Richards vociferously opposed the use of the term “prisoners” in connection with the league, arguing that the prisoners should refer to themselves as “men.” “I think we should not appeal to the men outside as ‘prisoners’ but as ‘men,’” Richards insisted, “Man to Man is my idea.” On another level, the delegates recognized that the constitution must persuade prisoners that the league was worth joining. Richards, again arguing against the use of the term, “prisoners,” put it in a way that resonated with the Good Word’s analysis of the peculiar effect of incarceration on the consciousness of the prisoner:

I am a prisoner, I know it, but I am only a prisoner for a short period during the day. If you go to a new man and aks (sic) him to join a Prisoner’s League, he says, Oh, why don’t you let me alone and let me forget that I am a prisoner once in a while. I myself when I go to my room at night and lay down on my bed forget that I am a prisoner, as I do when I am working during the day time. I know I am a prisoner, but I want to forget it as much as I can, and I don’t care to have the word thrust upon me on every occasion that I turn around.

Richards prevailed, and the word was dropped from the final version of the constitution in favor of “men.”

The delegates’ resolution to remove from the document any reference to themselves as prisoners mystified the real relations of incarceration by obfuscating the objective fact of the prisoners’ forced detainment within well-patrolled prison walls. However, the prisoners also implicitly acknowledged those relations, by writing a constitution that was aimed at winning the support of the people who had the power to change the conditions of incarceration. Finally, as the constitutional convention drew to a close, the men behind bars agreed on the name of their new organization. Having started with fifty suggestions for a name for the new league (including one honoring Osborne – the “Tom Brown League”), the forty-nine delegates eventually decided to name their organization the “Mutual Welfare League.” With the thirteen resolutions agreed to, the constitutional convention was dissolved and the delegates prepared to address the prison population at large the following day

Exactly three weeks after Osborne had first addressed the Auburn prisoners and announced plans to set up a prisoner organization, all but a few of the 1,400 prisoners gathered in the chapel to hear about the formation of the MWL and its constitution and bylaws. For the first time in the history of Auburn prison, the guards withdrew from the chapel, leaving Auburn’s prisoners to conduct their meeting without supervision. Osborne, chairing the meeting once again, read the draft of the constitution and bylaws to the assembled prisoners and then put it to a vote. According to secretary Richards, the prisoners unanimously endorsed it, whereupon the first election for the MWL was announced for January 15. Upon the initiative of Osborne, a motion was passed to thank Warden Rattigan for allowing the prisoners the opportunity to form a league, and, at this peculiar prison rally, where prisoners discussed liberty while men with “sticks and bluecoats” patrolled outside, the prisoners of Auburn concluded their assembly by rising to sing the anthem, “My Country ‘Tis of Thee.”

The deliberations of the Committee of Twelve and the forty-nine delegates over the previous week had revealed the tensions and contradictions that were inherent in the practice of prisoner self-government. In their efforts to graft the organs of democracy onto the prison body, Osborne and Warden Rattigan were masking the real relations of power in the prison. Most critically, although Osborne and his supporters insisted that the impetus for the league had come from the prisoners themselves, it is clear that Osborne had instigated and guided its creation. The authority to organize this prison-based representative democracy emanated from the warden and the Superintendent of Prisons, and its survival depended upon the continued support of both. Although the prisoners elected delegates to frame a constitution, and delegates argued over the critical questions of policing and discipline, Osborne’s selection of a special (and small) committee of drafters, his marshaling of the discussions, and the defeat of dissenting opinion, make it clear that Osborne and his supporters were engaged in an elaborate staging of democracy. In this respect, prisoner self-government was instigated from the top down; it was not an organic or democratic movement, and it certainly was not generated from below – that is, from within the prisoners’ ranks – as Osborne claimed.

One incident in particular provides a remarkable illustration of Osborne’s mystification of the operations of power in the prison. This incident involved him masking his own relation to the prisoners: During the New Year’s Day meeting of the Committee of Twelve, Osborne had suggested that the warden, Superintendent Riley, and himself be made honorary members of the league. In response to this suggestion, delegate Cameron noted that this was a good idea, and that “It is too bad that (the) idea did not originate with one of us [the prisoners].” When Osborne retorted, “I am one of you,” Cameron rejoined, “– Without the coat,” whereupon Osborne reached for a prisoner’s regulation coat and exclaimed, “I will put on the coat. I have it here. Here goes.” Of course, as Shea and his fellow prisoners no doubt knew full well, coat or no coat, Osborne was not a prisoner but an elite reformer whose opinion invariably trumped that of the prisoner delegates. At the end of that particular meeting, “Tom Brown” took off the prison coat, uttered words that only a freeman would – “I must be going” – and walked out of the prison the same way he had entered it – a free citizen. (Perhaps the irony of the incident was not lost on secretary Richards, who reported the conversation in full).

As he made clear in the prisoner meetings, Osborne sought to make an inherently coercive institution into a cooperative one. His recourse to pedagogical penology missed the point that delegates repeatedly made about the prison’s inherently violent character, its high mortality rate, and its incidence of injury and disease. At one point during the New Year’s Day meeting, the delegates discussed the procedure by which an elected delegate could be relieved of his duties should he be beaten, die, or be taken ill. A few moments later, Osborne, who had had little to add to this discussion of the peculiar violence to which prisoners were subject, offered the term limits of the student body at his alma mater, Harvard University, as a model of electoral fairness. Although the prisoners seemed not to agree with Osborne’s argument that guard–prisoner relations were falsely oppositional, they did grasp the relations of power that existed between Osborne and themselves: They disagreed over certain issues, but they never drew attention to the incongruity or simple absurdity of some of Osborne’s analogies, nor did they vote against his suggestions. As the fate of the league attests, the new techniques of cooperation constituted a novel form of carceral coercion, and these practices obfuscated the real power relations of the prisons.

...prisoners were able to put the league and the new privileges to their own uses, but these were always circumscribed by the fact that prisoners were physically held in a carceral system they could not leave, and that, as delegate Shea put it most precisely, prisoners at any and all times remained subject to the guard with “that blue coat and that stick.” However, all this is not to say that prisoners had no use for Osborne or the league; on the contrary, it generated new possibilities for prisoners’ ongoing attempts to improve their lot and to hold the state to its official policy of amelioration, on both an individual and collective basis."

- Rebecca M. McLennan, The Crisis of Imprisonment: Protest, Politics, and the Making of the American Penal State, 1776-1941. Cambridge University Press, 2008. p. 339-356

Image shows a (highly scripted) rally of the Mutual Welfare League before the Warden sometime in summer 1914. From the book

#auburn prison#mutual welfare league#penal reform#progressive penology#prisoner self-goverment#prison democracy#thomas mott osborne#prison discipline#freedom of the yard#prison administration#crisis of imprisonment#new york prisons#history of crime and punishment#academic quote#reading 2023

1 note

·

View note

Text

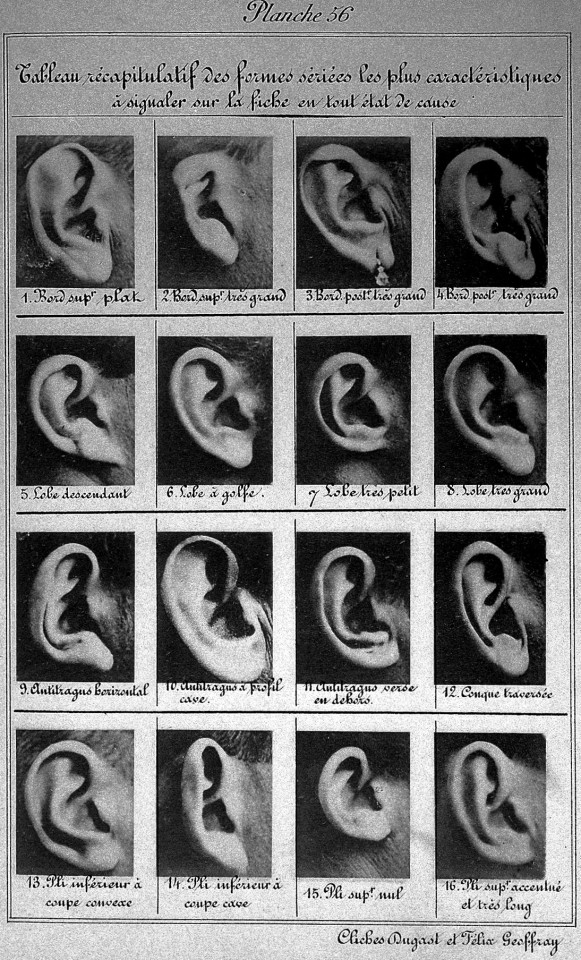

Sculpey Ear Trial Research

He was a French police officer who introduced formal ways to map and record the criminal, in 1882 he introduced his system of identification, which incorporates a series of refined bodily measurements, physical description, and photographs. He did not invent the fingerprint system but Bertillon was the first on the in Europe to use fingerprints to solve a crime.

0 notes

Text

Alphonse Bertillon, a nineteenth-century French policeman, came up with a system of identifying criminals by using their distinguishing characteristics.

This involved not only measurements but classifications of types of features on the human body. Bertillon came up with typologies of different parts of the face and head, for example. Here’s his table of ear types.

Full story here:

{WHF} {Ko-Fi} {Medium}

99 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alphonse Bertillion was a french criminologist and anthropologist, he created the methods he did because he didn't like the unsystematic methods he was being given to use, so he made his own. in the early stages of forensics and identification, the Bertillion system created by Alphonse Bertillion, was a method of suspect identification using anthropometry. one of the methods was comparing the shapes of a suspect's ear shape to any ear prints that could have possibly been left at a crime scene, for example it was possible for ear prints to be left at break-ins if the perpetrator pressed their face against a window and left a mark. It was found that every person's ear is different from the next an that they are as unique as finger prints. he also developed the process of measuring arms, ears, nose, trunk, head, face, feet and hands, as well standing height, sitting height, distance between fingertips and arms outstretched to identify specific characteristics. during the 19th century, there were cases of prostitutes working in alleys, and the Bertillion system was used to identify them and their crimes. He use his method to identify over 240 offenders in 1884, and s his methods were reognised and adopted across the world in places such as Great Britain, America and other European countries outside of France.

Bertillion also is the creator of the mugshot. "Bertillon also created many other forensics techniques, including the use of galvanoplastic compounds to preserve footprints, ballistics, and the dynamometer, used to determine the degree of force used in breaking and entering."

The Bertillion system is actually referenced in Sherlock Holmes, in The Hound of the Baskervilles in 1902. one of Holmes' clients refers to Holmes as the "second highest expert in Europe" after Bertillon. Bertillion being included in such a well known series i regards to his intelligence shows how influential his discoveries and methods were for the time period. To this day a mugshot is required for every arrest, and despite having updated identification methods such as the fingerprint and DNA samples, Bertillion's efforts do not go unused. his methods of using scars, tattoos and eye colour are still maintained today in forensics.

0 notes