#biblical linguists

Text

started biblical hebrew studies all over confident like "this grammar shit is easy" and have now been introduced to the souls boss that is Prepositions.

#i speak french and some russian so noun and verb moods aren't too bad#but lord i thought french prepositions were confusing...#this is a whole other game#dying.#linguistics#jumblr#biblical hebrew

12 notes

·

View notes

Link

The Dead Sea Scrolls, first uncovered by a trio of Bedouin wandering the Judean Desert in 1947, provide a fascinating glimpse into what Scripture looked like during a transformative period of religious ferment in ancient Israel. The scrolls include the oldest copies ever found of the Hebrew Bible, “apocryphal” texts that were never canonized, and rules and guidelines for daily living written by the community of people who lived at Qumran, where the first scrolls were found. All told, scholars have identified as many as 100,000 Dead Sea Scrolls fragments, which come from more than 1,000 original manuscripts.

Experts date the scrolls between the third century B.C. and the first century A.D. (though Langlois believes several may be two centuries older). Some of them are relatively large: One copy of the Book of Isaiah, for example, is 24 feet long and contains a near-complete version of this prophetic text. Most, however, are much smaller—inscribed with a few lines, a few words, a few letters. Taken together, this amounts to hundreds of jigsaw puzzles whose thousands of pieces have been scattered over many different locations around the world.

In 2012, Langlois joined a group of scholars working to decipher close to 40 Dead Sea Scrolls fragments in the private collection of Martin Schøyen, a wealthy Norwegian businessman. Each day in Kristiansand, Norway, he and specialists from Israel, Norway and the Netherlands spent hours trying to determine which known manuscripts the fragments had come from. “It was like a game for me,” Langlois said. The scholars would project an image of a Schøyen fragment on the wall beside a photograph of a known scroll and compare them. “I’d say, ‘No, it’s a different scribe. Look at that lamed,’” Langlois recalled, using the word for the Hebrew letter L. Then they would skip forward to another known manuscript. “No,” Langlois would say. “It’s a different hand.”

Each morning, while out walking, the scholars discussed their work. And each day, according to Esti Eshel, an Israeli epigrapher also on the team, “They were killing another identification.” Returning to France, Langlois examined the fragments with computer-imaging techniques he had developed to isolate and reproduce each letter written on the fragments before beginning a detailed graphical analysis of the writing. And what he discovered was a series of flagrant oddities: A single sentence might contain styles of script from different centuries, or words and letters were squeezed and distorted to fit into the available space, suggesting the parchment was already fragmented when the scribe wrote on it. Langlois concluded that at least some of Schøyen’s fragments were modern forgeries. Reluctant to break the bad news, he waited a year before telling his colleagues. “We became convinced that Michael Langlois was right,” said Torleif Elgvin, the Norwegian scholar leading the effort.

After further study, the team ultimately determined that about half of Schøyen’s fragments were likely forgeries. In 2017, Langlois and the other Schøyen scholars published their initial findings in a journal called Dead Sea Discoveries. A few days later, they presented their conclusions at a meeting in Berlin of the Society of Biblical Literature. Flashing images of the Schøyen fragments on a screen, Langlois described the process by which he concluded the pieces were fakes. He quoted from his contemporaneous notes on the scribe’s “hesitant hand.” He pointed out inconsistencies in the fragments’ script.

And then he dropped the gauntlet: The Schøyen fragments were only the beginning. The previous year, he said, he’d seen photos of several Dead Sea Scrolls fragments in a book published by the Museum of the Bible, in Washington, D.C., a privately funded complex a few blocks from the U.S. Capitol. The museum was scheduled to open its doors in three months, and a centerpiece of its collection was a set of 16 Dead Sea Scrolls fragments whose writing, Langlois now said, looked unmistakably like the writing on the Schøyen fragments. “All of the fragments published there exhibited the same scribal features,” he told the scholars in attendance. “I’m sorry to say that all of the fragments published in this volume are forgeries. This is my opinion.”

The weight of the evidence presented that day by several members of the Schøyen team led to a re-evaluation of Dead Sea Scrolls in private collections all over the world. In 2018, Azusa Pacific University, a Christian college in Southern California that had purchased five scrolls in 2009, conceded that they were likely fakes, and it sued the dealer who had sold them. In 2020, the Southwestern Baptist Theological Seminary, in Fort Worth, Texas, announced that the six Dead Sea Scrolls it had purchased around the same time were also “likely fraudulent.”

The most stunning admission came from executives at the Museum of the Bible: They had hired an art-fraud investigator to examine the museum’s fragments using advanced imaging techniques and chemical and molecular analysis. In 2020, the museum announced that its prized collection of Dead Sea Scrolls was made up entirely of forgeries.

Langlois told me that he derives no pleasure from such discoveries. “My intention wasn’t to be an expert in forgeries, and I don’t love catching bad guys or something,” he told me. “But with forgeries, if you don’t pay attention, and you think they are authentic, then they become part of the data set you use to reconstruct the history of the Bible. The entire theory is then based on data that is false.” That’s why ferreting out biblical fakes is “paramount,” Langlois said. “Otherwise, everything we are going to do on the history of the Bible is corrupt.”

#history#languages#linguistics#religion#christianity#judaism#forgery#biblical hebrew#bible#dead sea scrolls#michael langlois

70 notes

·

View notes

Text

Help an old woman at my church who has forcibly adopted me is now making me learn biblical hebrew, my little linguist heart is already studying Spanish and Esperanto help. I love it. I'm drowning in words

#linguistics#biblical hebrew#esperanto#save me#adams-oliver syndrome#ive been forcibly adopted#what do i do its so hard trying to learn to read right to left#old church ladies back on their grind

4 notes

·

View notes

Note

How comprehensible is New Testament Greek to modern Greek people?

Very, almost entirely. My impression is that: a) People of a generally good education (not lingual, just generally high school - college education) can understand 91-99% of it without problem. b) People of a basic education (elementary - middle school) can still make about 80-90% of it. c) For people taking lingual studies it is a stroll in the park, needless to say.

Still, Greek bibles always come with a modern translation too but it is mostly useful for “confirmation” rather than interpretation, as in, double-checking to ensure you understood correctly if you need.

A little known fact to foreign people is that Koine / Biblical Greek is lingually closer to Modern rather than Ancient Greek.

#Greek#Greek language#languages#linguistics#langblr#Koine Greek#biblical Greek#bible#New Testament#Christianity#Greek facts#emmenai-kalliston#ask

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

Learning about biblical Hebrew verbs and it's driving me crazy with excitement!! Aspect instead of tense? Volitional conjugation for 1st, 2nd, AND 3rd person?? Certain verb stems indicating the intensity of the action??? This is so unbelievably cool!!! I'm rocking back and forth in excitement

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Enoch, an apocryphal text thought to be written sometime between the third century B.C. and the second century A.D., is named for the biblical Noah’s great-grandfather. One reason Langlois didn’t know much about the book was that it didn’t make it into the Hebrew Bible or the New Testament. Another is that the only complete copy to survive from antiquity was written in an ancient Ethiopic language called Ge’ez.

But beginning in the 1950s, more than 100 fragments from 11 different parchment scrolls of the Book of Enoch, written largely in Aramaic, were found among the Dead Sea Scrolls. A few fragments were relatively large—15 to 20 lines of text—but most were much smaller, ranging in size from a piece of toast to a postage stamp. Someone had to transcribe, translate and annotate all this “Enochic” material—and Langlois’ teacher volunteered him. That’s how he became one of just two students in Paris learning Ge’ez.

Langlois quickly grasped the numerous parallels between Enoch and other books of the New Testament; for instance, Enoch mentions a messiah called the “son of man” who will preside over the Final Judgement. Indeed, some scholars believe Enoch was a major influence on early Christianity, and Langlois had every intention to conduct that type of historical research.

He started by transcribing the text from two small Enoch fragments, but age had made parts of it hard to read; some sections were missing entirely. In the past, scholars had tried to reconstruct missing words and identify where in the larger text these pieces belonged. But after working out his own readings, Langlois noticed the fragments seemed to come from parts of the book that were different from those specified by earlier scholars. He also wondered if their proposed readings could even fit on the fragments they purportedly came from. But how could he tell for sure?

To faithfully reconstruct the text of Enoch, he needed digital images of the scrolls—images that were crisper and more detailed than the printed copies inside the books he was relying on. That was how, in 2004, he found himself traipsing around Paris, searching for a specialized microfiche scanner to upload images to his laptop. Having done that (and lacking cash to buy Photoshop), he downloaded an open-source knockoff.

First, he individually outlined, isolated and reproduced each letter on Fragment 1 and Fragment 2, so he could move them around his screen like alphabet refrigerator magnets, to test different configurations and to create an “alphabet library” for systematic analysis of the script. Next, he began to study the handwriting. Which stroke of a given letter was inscribed first? Did the scribe lift his pen, or did he write multiple parts of a letter in a continuous gesture? Was the stroke thick or thin?

Then Langlois started filling in the blanks. Using the letters he’d collected, he tested the reconstructions proposed by scholars over the preceding decades. Yet large holes remained in the text, or words were too big to fit in the available space. The “text” of the Book of Enoch as it was widely known, in other words, was in many cases mistaken.

Take the story of a group of fallen angels who descend to earth to seduce beautiful women. Using his new technique, Langlois discovered that earlier scholars had gotten the names of some of the angels wrong, and so had not realized the names were derived from Canaanite gods worshipped in the second millennium B.C.—a clear example of the way scriptural authors integrated elements of the cultures that surrounded them into their theologies. “I didn’t consider myself a scholar,” Langlois told me. “I was just a student wondering how we could benefit from these technologies.” Eventually, Langlois wrote a 600-page book that applied his technique to the oldest known scroll of Enoch, making more than 100 “improvements,” as he calls them, to prior readings.

His next book, even more ambitious, detailed his analysis of Dead Sea Scrolls fragments containing snippets of text from the biblical Book of Joshua. From these fragments he concluded that there must be a lost version of Joshua, previously unknown to scholars and extant only in a small number of surviving fragments. Since there are thousands of authentic Dead Sea Scrolls, it appears that much still remains to be learned about the origins of early biblical texts. “Even the void is full of information,” Langlois told me.

— How an Unorthodox Scholar Uses Technology to Expose Biblical Forgeries

#chanan tigay#michael langlois#how an unorthodox scholar uses technology to expose biblical forgeries#history#religion#christianity#judaism#canaanite religion#languages#linguistics#translation#palaeography#forgeries#bible#torah#dead sea scrolls#technology#digital technology#canaan#book of enoch#aramaic#ge'ez

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

a blog about learning biblical greek followed me and i feel like if i did start learning biblical greek, not one of you would be surprised.

#i think learning biblical greek would be fun 👀#and that's because i want to learn every language on the planet#i want to be a linguist 😩#if only i really were emilio sandoz; then i wouldn't be quite so traumatized yet and have the ability to do shit more than i do now#emilio.txt

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

breaking news: humanities girl manages to turn all four of her classes into classics courses no matter their subject matter. more at 5…

#for bio i am treating it like linguistics and it’s WORKING…. if i know the etymologies i pass the tests…..#for sem we are doing something about biblical translation from latin (i am um. also doing a little personal#research about latin poetic translation in general) latin is well. it’s latin.#and for western civ we are finally talking about my dear good friend the roman republic!!!!#samael speaks

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Learn Biblical Hebrew from Aleph to Tav

www.laciniagallery.com/aleph

#art#jesus christ#jesus is coming#jesusislord#linguistics#jesussaves#original art#traditional art#torah#writers#hebrew#biblicalhebrew#biblical art#biblical studies#biblical scripture#bible#salvation#resurrection#psalms#christianity

0 notes

Text

Sometimes I wonder if some people have likes and interest outside of the DSMP. Like. Sometimes I see shit and I’m like “child, get a life” there is so much more you can do than complain on the internet for 24 hours 7 days a week. Get a hobby. Eat some food. Watch a non-gaming video. Touch grass. Just??? Anything really???? Live your life please????

#personal#outside of tumblr#I spend most of my time watching history and writing videos#I especially enjoy food history#linguistic anthropology and conlangs#trope dissections and long form analyses#and biblical history#it’s very interesting#Especially when trying to the pre testament origins of the Bible

0 notes

Text

Thinking about this post. "The only way to make a cell is from another cell" is somewhat of a troubling fact to me. I mean, not for any practical reason, just because it underscores the precarity of *gestures broadly*.

It's like, some people talk about trying to de-extinct the mammoth. And people are trying to sequence the genome of the mammoth, I don't know if they've done it yet. But even if they do, one of the problems with the idea of de-extinction is... to grow a baby mammoth, you need another mammoth! Last time I heard people talking about this, I think they were talking about using an elephant as a surrogate mother. But imagine if elephants were extinct too.

The point is that information is often tied to the systems that transmit it; even if you know everything in the mammoth genome, once all the mammoths are gone there's nothing capable of reading and using that information. Like when you can't read the data on a perfectly good floppy disk because your computer doesn't have a floppy drive.

This is related to why language death troubles me so much. Even the most well-documented languages aren't actually that well understood; linguists have produced more pages of work on English syntax than maybe any other specific descriptive topic and yet still the only reliable way to get the answer to any moderately subtle syntactic question is elicit native speaker data. We know almost nothing, we can barely extrapolate at all! And every language is like this, a hugely complex system that we know basically nothing about, and if the chain of native speaker transmission is ever broken it's just gone.

"Language revival", I mean from a totally dead language, is kind of a myth. It's like the "came back different" trope. In Israel they revived Hebrew, but Modern Hebrew is really not the same thing as Biblical Hebrew at all. I mean in a stronger sense even than Modern English isn't Old English. All the subtleties of Biblical Hebrew that a native speaker would have had implicit competence with died without a trace. All they left is a grainy image, the texts. The first generation of Modern Hebrew speakers took the rough grammatical sketch preserved in these texts and imbued it with new subtleties, borrowed from Slavic and Germanic and the speakers' other native languages, or converged at by consensus among that first generation of children. There's nothing wrong with that, but it would be inaccurate to imagine Biblical Hebrew surviving in Modern Hebrew the way Old English survives in Modern English. For instance, you can discover a great deal that you didn't know about Old English by comparing Modern English dialects. There is nothing you can discover about Biblical Hebrew by comparing Modern Hebrew dialects in this way.

There's nothing wrong with this, of course. I'm not like, judging Modern Hebrew. I'm just making a point.

Mammoths died recently, so we still have (some of?) their genome. Something that died longer ago, like dinosaurs, we have traces of them in the form of fossils but we could never hope to revive them, the information is just gone. Even if we're not aiming for revival, even if we just want to know stuff about dinosaurs, there's so much that we will never know and can never know.

We imagine information as the kind of thing which sits in an archive, because this is the context most of us encounter information in, I think. Libraries, hard drives. Well obviously hard drives don't last. And most ancient texts only survive because of a scribal tradition, continuous re-writing, not because of actual archival. So I think that imagining archives as the natural habitat of information is sort of wrong; the natural habit of information is in continuous transmission. Information is constantly moving. And it's like one of those sharks, if it ever stops moving it drowns. And if the lines of transmission are broken, the information is gone and can never be retrieved.

Very precarious.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

oh routledge language textbooks thank you for my life

#still trying to learn biblical hebrew....#even the basic vowel rules were so confusing but the way this book explained it made it finally click#im using the introductory course in biblical hebrew btw#im also doing the modern hebrew one and i really like how strict it is with immersion#like right off with exercise 1...#linguistics#biblical hebrew#modern hebrew

1 note

·

View note

Text

Gonna start saying "Biblically accurate" when I just mean "canon." Or even just "appropriate," probably. Gonna be my new "literally."

#my life right now#let's make it happen#biblically accurate#canon#literally#slang#linguistic degradation#let's muddy these waters#willfully obtuse#obfuscation

1 note

·

View note

Text

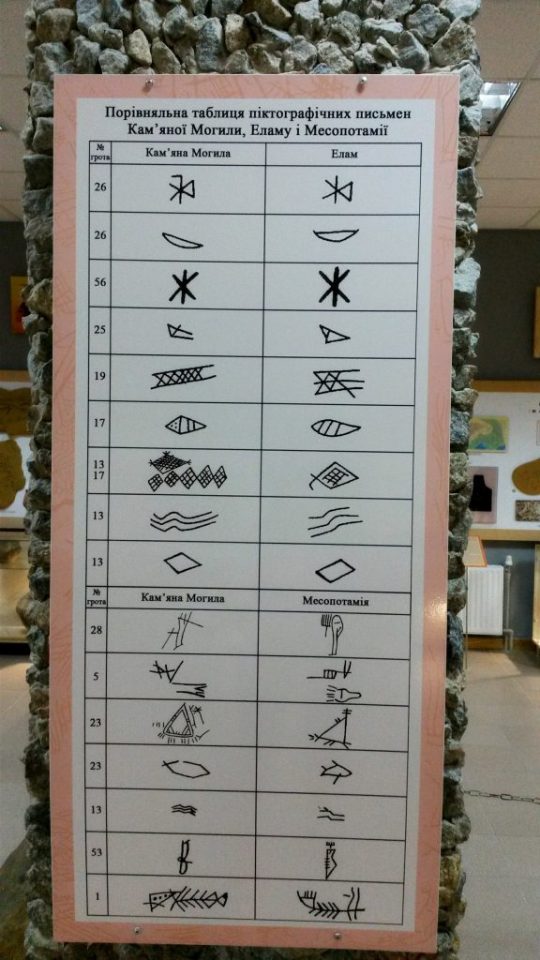

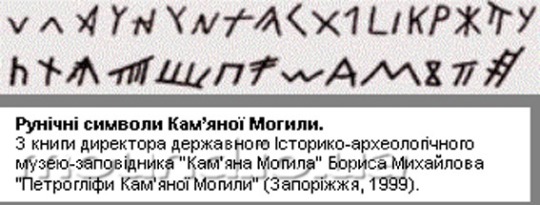

Kamyana Mohyla is believed to contain the first writing in the world.

According to the Ukrainian scientist I. M. Rassokha, most of the inscriptions of Kamyana Mohyla have direct parallels with the ancient Ogamic inscriptions of the British Isles, Germanic "coniferous" runes, ancient Slavic "strokes and cuts", etc., that is, it can be a monument of the most ancient sacred writing of the era of Indo-European unity, namely the Seredniy Stog culture of the 4th millennium BC.

The famous linguist N. Marr proved that the Ukrainian verb "to search" (шукати - shukaty) comes from the Sumerian "shu" - "hand". The Kyivan researcher S. Paukov believes that the Ukrainian words "shana" (honour) and "shanuvaty" (to pay respect) also came from the Sumerian "Shu-Nun" (which is believed to mean "the hand of the queen).

The Sumerologist A.G. Kyfishyn studied the inscriptions of the Kamyana Mohyla (VII-III millennia BC) for a long time and found many parallels with inscriptions on clay tablets of the civilizations of Elam and Mesopotamia (Sumeria): This "writing", as he believes, was invented by the "proto-Sumerians" who lived in "Ukrainian Aratta" as early as the 12th millennium BC, and from there this ancient ethnic group apparently moved to Mesopotamia after the flooding of the Northern Black Sea, which, according to G.A. Kyfishyn, reflected in the biblical message about the World Flood.

Kamyana Mohyla has been occupied by russians since 2022.

123 notes

·

View notes

Text

““Dorothy reminds me in so many ways of Toni Morrison,” West said. “You know Toni Morrison is Catholic. Many people do not realize that she is one of the great Catholic writers. Like Flannery O’Connor, she has an incarnational conception of human existence. We Protestants are too individualistic. I think we need to learn from Catholics who are always centered on community.”

(…)

She viewed belief in God as “an intellectual experience that intensifies our perceptions and distances us from an egocentric and predatory life, from ignorance and from the limits of personal satisfactions”—and affirmed her Catholic identity. “I had a moment of crisis on the occasion of Vatican II,” she said. “At the time I had the impression that it was a superficial change, and I suffered greatly from the abolition of Latin, which I saw as the unifying and universal language of the Church.”

Morrison saw a problematic absence of authentic religion in modern art: “It’s not serious—it’s supermarket religion, a spiritual Disneyland of false fear and pleasure.” She lamented that religion is often parodied or simplified, as in “those pretentious bad films in which angels appear as dei ex machina, or of figurative artists who use religious iconography with the sole purpose of creating a scandal.” She admired the work of James Joyce, especially his earlier works, and had a particular affinity for Flannery O’Connor, “a great artist who hasn’t received the attention she deserves.”

What emerges from Morrison’s public discussions of faith is paradoxical Catholicism. Her conception of God is malleable, progressive, and esoteric. She retained a distinct nostalgia for Catholic ritual, and feels the “greatest respect” for those who practice the faith, even if she herself wavered. In a 2015 interview with NPR, Morrison said there was not a “structured” sense of religion in her life at the moment, but “I might be easily seduced to go back to church because I like the controversy as well as the beauty of this particular Pope Francis. He’s very interesting to me.”

Morrison’s Catholic faith—individual and communal, traditional and idiosyncratic—offers a theological structure for her worldview. Her Catholicism illuminates her fiction; in particular, her views of bodies, and the narrative power of stories. An artist, Morrison affirmed, “bears witness.” Her father’s ghost stories, her mother’s spiritual musicality, and her own youthful sense of attraction to Christianity’s “scriptures and its vagueness” led her to conclude it is “a theatrical religion. It says something particularly interesting to black people, and I think it’s part of why they were so available to it. It was the love things that were psychically very important. Nobody could have endured that life in constant rage.” Morrison said it is a sense of “transcending love” that makes “the New Testament . . . so pertinent to black literature—the lamb, the victim, the vulnerable one who does die but nevertheless lives.”

(…)

Morrison is describing a Catholic style of storytelling here, reflected in the various emotional notes of Mass. The religion calls for extremes: solemnity, joy, silence, and exhortation. Such a literary approach is audacious, confident, and necessary, considering Morrison’s broader goals. She rejected the term experimental, clarifying “I am simply trying to recreate something out of an old art form in my books—the something that defines what makes a book ‘black.’”

(…)

Morrison was both storyteller and archivist. Her commitment to history and tradition itself feels Catholic in orientation. She sought to “merge vernacular with the lyric, with the standard, and with the biblical, because it was part of the linguistic heritage of my family, moving up and down the scale, across it, in between it.” When a serious subject came up in family conversation, “it was highly sermonic, highly formalized, biblical in a sense, and easily so. They could move easily into the language of the King James Bible and then back to standard English, and then segue into language that we would call street.”

Language was play and performance; the pivots and turns were “an enhancement for me, not a restriction,” and showed her that “there was an enormous power” in such shifts. Morrison’s attention toward language is inherently religious; by talking about the change from Latin to English Mass as a regrettable shift, she invokes the sense that faith is both content and language; both story and medium.

From her first novel on forward, Morrison appeared intent on forcing us to look at embodied black pain with the full power of language. As a Catholic writer, she wanted us to see the body on the cross; to see its blood, its cuts, its sweat. That corporal sense defines her novel Beloved (1988), perhaps Morrison’s most ambitious, stirring work. “Black people never annihilate evil,” Morrison has said. “They don’t run it out of their neighborhoods, chop it up, or burn it up. They don’t have witch hangings. They accept it. It’s almost like a fourth dimension in their lives.”

(…)

Morrison has said that all of her writing is “about love or its absence.” There must always be one or the other—her characters do not live without ebullience or suffering. “Black women,” Morrison explained, “have held, have been given, you know, the cross. They don’t walk near it. They’re often on it. And they’ve borne that, I think, extremely well.” No character in Morrison’s canon lives the cross as much as Sethe, who even “got a tree on my back” from whipping. Scarred inside and out, she is the living embodiment of bearing witness.

(…)

Morrison’s Catholicism was one of the Passion: of scarred bodies, public execution, and private penance. When Morrison thought of “the infiniteness of time, I get lost in a mixture of dismay and excitement. I sense the order and harmony that suggest an intelligence, and I discover, with a slight shiver, that my own language becomes evangelical.” The more Morrison contemplates the grandness and complexity of life, the more her writing reverts to the Catholic storytelling methods that enthralled her as a child and cultivated her faith. This creates a powerful juxtaposition: a skilled novelist compelled to both abstraction and physicality in her stories. Catholicism, for Morrison, offers a language to connect these differences.

For Morrison, the traits of black language include the “rhythm of a familiar, hand-me-down dignity [that] is pulled along by an accretion of detail displayed in a meandering unremarkableness.” Syntax that is “highly aural” and “parabolic.” The language of Latin Mass—its grandeur, silences, communal participation, coupled with the congregation’s performative resurrection of an ancient tongue—offers a foundation for Morrison’s meticulous appreciation of language.

Her representations of faith—believers, doubters, preachers, heretics, and miracles—are powerful because of her evocative language, and also because she presents them without irony. She took religion seriously. She tended to be self-effacing when describing her own belief, and it feels like an action of humility. In a 2014 interview, she affirmed “I am a Catholic” while explaining her willingness to write with a certain, frank moral clarity in her fiction. Morrison was not being contradictory; she was speaking with nuance. She might have been lapsed in practice, but she was culturally—and therefore socially, morally—Catholic.

The same aesthetics that originally attracted Morrison to Catholicism are revealed in her fiction, despite her wavering of institutional adherence. Her radical approach to the body also makes her the greatest American Catholic writer about race. That one of the finest, most heralded American writers is Catholic—and yet not spoken about as such—demonstrates why the status of lapsed Catholic writers is so essential to understanding American fiction.

A faith charged with sensory detail, performance, and story, Catholicism seeps into these writers’ lives—making it impossible to gauge their moral senses without appreciating how they refract their Catholic pasts. The fiction of lapsed Catholic writers suggests a longing for spiritual meaning and a continued fascination with the language and feeling of faith, absent God or not: a profound struggle that illuminates their stories, and that speaks to their readers.”

42 notes

·

View notes

Note

pleaaase share any and all thoughts you might have on as i lay dying by william faulkner if you're willing, i'd appreciate your analysis on any topic dealing with it. I recently had to read it for class and kept thinking "tumblr user transmutationisms would probably find this very interesting" and when I search your blog i see its one of your fav novels! personally am interested with the treatment of darl and what is considered "sane" vs. "insane" as well as addie and how her death is handled.

yeah this book made me so insane when i first encountered it lmao. i was always surprised by people who read it and thought that darl had genuinely or intrinsically 'gone insane' or even that he was in some kind of decline throughout the book. i thought what faulkner was doing with him was very different.

i'd posit there are basically 2 main mechanisms by which darl comes to be regarded as insane. one is the construal of criminal action as prima facie pathological. in darl's case it's specifically criminal action against his mother's body (so, the violation of a blood tie that is so important it has guided the entire novel) and ofc the barn burning has a more general sort of antisocial effect as well. so, the designation of insanity follows not because darl's action shows some kind of intrinsic breakdown or loss of lucidity, but because it puts him outside the bounds of accepted familial and social behaviours. so, in that sense there's a very straightforward connection between the social mores, the criminal code based on them, and the invocation of insanity to preserve the dichotomy between 'sane' and 'criminal', ofc with the asylum then appearing as another arm of the carceral / criminal apparatus.

in addition, though, faulkner's work is generally marked by an interest in the sort of social breakdown and decline that articulates along family lines. which is to say: although i wouldn't attribute to him the same degree of evolutionary-hereditarian degeneracy theory as, like, zola, there is certainly a repeated interest throughout faulkner's work in the family as a site of inherited social and economic decline. i don't think the point here is to write anse as insane, per se, or as passing on a discrete malady to darl, but parentage matters (cf. jewel's illegitimacy) and in the same way that anse is antisocial, illogical, and frequently illegible to the surrounding characters, darl by the end of the book has come to occupy a similar socially marginal position. darl is ofc punished more violently for his transgression; anse's chapters convey pretty clearly his outsider position and complete inability to make sense of the world on linguistic-logical terms, but darl escalates this when he burns the barn because he's breaking a rule that has more external social ramifications than, say, anse's biblical exegesis about snakes and trees and whatever.

broadly and kind of annoyingly you could say the novel is investigating the relationship between consciousness and language, or at least feeling and language. the words are "a shape to fill a lack", vardaman's fish chapter sort of sums up the failings therein, &c. so, anse and darl are interesting to counterpose in this respect because the disconnect between their inner worlds and linguistic abilities are very different. darl is the most linguistically adept narrator in the book, yet by the end he's committed an act so illegible to the state and to his community that he's declared insane for it. anse, on the other hand, is motivated by what is in certain ways a very clear and simple moral code (he is driven primarily throughout the novel by the desire to bury addie and then take care of his own material needs re: teeth and a new wife), but he's not really able to communicate this directly in narration, which makes his chapters some of my favs to re-read. with anse the stream-of-consciousness is continually hinting at and around what he's trying to convey; with darl there are certainly things he's capable of expressing clearly and directly in language, and so the effect (for me) is to surprise you when it's revealed that darl, too, is on a kind of margin of social logic.

59 notes

·

View notes