#biodiversity crisis

Text

There, in the sunlit forest on a high ridgeline, was a tree I had never seen before.

I spend a lot of time looking at trees. I know my beech, sourwood, tulip poplar, sassafras and shagbark hickory. Appalachian forests have such a diverse tree community that for those who grew up in or around the ancient mountains, forests in other places feel curiously simple and flat.

Oaks: red, white, black, bur, scarlet, post, overcup, pin, chestnut, willow, chinkapin, and likely a few others I forgot. Shellbark, shagbark and pignut hickories. Sweetgum, serviceberry, hackberry, sycamore, holly, black walnut, white walnut, persimmon, Eastern redcedar, sugar maple, red maple, silver maple, striped maple, boxelder maple, black locust, stewartia, silverbell, Kentucky yellowwood, blackgum, black cherry, cucumber magnolia, umbrella magnolia, big-leaf magnolia, white pine, scrub pine, Eastern hemlock, redbud, flowering dogwood, yellow buckeye, white ash, witch hazel, pawpaw, linden, hornbeam, and I could continue, but y'all would never get free!

And yet, this tree is different.

We gather around the tree as though surrounding the feet of a prophet. Among the couple dozen of us, only a few are much younger than forty. Even one of the younger men, who smiles approvingly and compliments my sharp eye when I identify herbs along the trail, has gray streaking his beard. One older gentleman scales the steep ridge slowly, relying on a cane for support.

The older folks talk to us young folks with enthusiasm. They brighten when we can call plants and trees by name and list their virtues and importance. "You're right! That's Smilax." "Good eye!" "Do you know what this is?—Yes, Eupatorium, that's a pollinator's paradise." "Are you planning to study botany?"

The tree we have come to see is not like the tall and pillar-like oaks that surround us. It is still young, barely the diameter of a fence post. Its bark is gray and forms broad stripes like rivulets of water down smooth rock. Its smooth leaves are long, with thin pointed teeth along their edges. Some of the group carefully examine the bark down to the ground, but the tree is healthy and flourishing, for now.

This tree is among the last of its kind.

The wood of the American Chestnut was once used to craft both cradles and coffins, and thus it was known as the "cradle-to-grave tree." The tree that would hold you in entering this world and in leaving it would also sustain your body throughout your life: each tree produced a hundred pounds of edible nuts every winter, feeding humans and all the other creatures of the mountains. In the Appalachian Mountains, massive chestnut trees formed a third of the overstory of the forest, sometimes growing larger than six feet in diameter.

They are a keystone species, and this is my first time seeing one alive in the wild.

It's a sad story. But I have to tell you so you will understand.

At the turn of the 20th century, the chestnut trees of Appalachia were fundamental to life in this ecosystem, but something sinister had taken hold, accidentally imported from Asia. Cryphonectria parasitica is a pathogenic fungus that infects chestnut trees. It co-evolved with the Chinese chestnut, and therefore the Chinese chestnut is not bothered much by the fungus.

The American chestnut, unlike its Chinese sister, had no resistance whatsoever.

They showed us slides with photos of trees infected with the chestnut blight earlier. It looks like sickly orange insulation foam oozing through the bark of the trees. It looks like that orange powder that comes in boxes of Kraft mac and cheese. It looks wrong. It means death.

The chestnut plague was one of the worst ecological disasters ever to occur in this place—which is saying something. And almost no one is alive who remembers it. By the end of the 1940's, by the time my grandparents were born, approximately three to four billion American chestnut trees were dead.

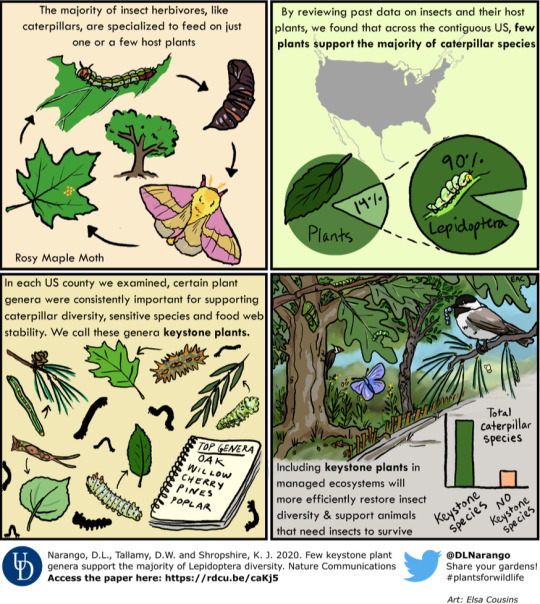

The Queen of the Forest was functionally extinct. With her, at least seven moth species dependent on her as a host plant were lost forever, and no one knows how much else. She is a keystone species, and when the keystone that holds a structure in place is removed, everything falls.

Appalachia is still falling.

Now, in some places, mostly-dead trees tried to put up new sprouts. It was only a matter of time for those lingering sprouts of life.

But life, however weak, means hope.

I learned that once in a rare while, one of the surviving sprouts got lucky enough to successfully flower and produce a chestnut. And from that seed, a new tree could be grown. People searched for the still-living sprouts and gathered what few chestnuts could be produced, and began growing and breeding the trees.

Some people tried hybridizing American and Chinese chestnuts and then crossing the hybrids to produce purer American strains that might have some resistance to the disease. They did this for decades.

And yet, it wasn't enough. The hybrid trees were stronger, but not strong enough.

Extinction is inevitable. It's natural. There have been at least five mass extinctions in Earth's history, and the sixth is coming fast. Many people accepted that the American chestnut was gone forever. There had been an intensive breeding program, summoning all the natural forces of evolution to produce a tree that could survive the plague, and it wasn't enough.

This has happened to more species than can possibly be counted or mourned. And every species is forced to accept this reality.

Except one.

We are a difficult motherfucker of a species, aren't we? If every letter of the genome's book of life spelled doom for the Queen of the Forest, then we would write a new ending ourselves. Research teams worked to extract a gene from wheat and implant it in the American chestnut, in hopes of creating an American chestnut tree that could survive.

This project led to the Darling 58, the world's first genetically modified organism to be created for the purpose of release into the wild.

The Darling 58 chestnut is not immune, the presenters warned us. It does become infected with the blight. And some trees die. But some live.

And life means hope.

In isolated areas, some surviving American Chestnut trees have been discovered, most of them still very young. The researchers hope it is possible that some of these trees may have been spared not because of pure luck, but because they carry something in their genes that slows the blight in doing its deadly work, and that possibly this small bit of innate resistance can be shaped and combined with other efforts to create a tree that can live to grow old.

This long, desperate, multi-decade quest is what has brought us here. The tree before me is one such tree: a rare survivor. In this clearing, a number of other baby chestnut trees have been planted by human hands. They are hybrids of the Darling 58 and the best of the best Chinese/American hybrids. The little trees are as prepared for the blight as we can possibly make them at this time. It is still very possible that I will watch them die. Almost certainly, I will watch this tree die, the one that shades us with her young, stately limbs.

Some of the people standing around me are in their 70's or 80's, and yet, they have no memory of a world where the Queen of the Forest was at her full majesty. The oldest remember the haunting shapes of the colossal dead trees looming as if in silent judgment.

I am shaken by this realization. They will not live to see the baby trees grow old. The people who began the effort to save the American chestnut devoted decades of their lives to these little trees, knowing all the while they likely never would see them grow tall. Knowing they would not see the work finished. Knowing they wouldn't be able to be there to finish it. Knowing they wouldn't be certain if it could be finished.

When the work began, the technology to complete it did not exist. In the first decades after the great old trees were dead, genetic engineering was a fantasy.

But those that came before me had to imagine that there was some hope of a future. Hope set the foundation. Now that little spark of hope is a fragile flame, and the torch is being passed to the next generation.

When a keystone is removed, everything suffers. What happens when a keystone is put back into place? The caretakers of the American chestnut hope that when the Queen is restored, all of Appalachia will become more resilient and able to adapt to climate change.

Not only that, but this experiment in changing the course of evolution is teaching us lessons and skills that may be able to help us save other species.

It's just one tree—but it's never just one tree. It's a bear successfully raising cubs, chestnut bread being served at a Cherokee festival, carbon being removed from the atmosphere and returned to the Earth, a wealth of nectar being produced for pollinators, scientific insights into how to save a species from a deadly pathogen, a baby cradle being shaped in the skilled hands of an Appalachian crafter. It's everything.

Despair is individual; hope is an ecosystem. Despair is a wall that shuts out everything; hope is seeing through a crack in that wall and catching a glimpse of a single tree, and devoting your life to chiseling through the wall towards that tree, even if you know you will never reach it yourself.

An old man points to a shaft of light through the darkness we are both in, toward a crack in the wall. "Do you see it too?" he says. I look, and on the other side I see a young forest full of sunlight, with limber, pole-size chestnut trees growing toward the canopy among the old oaks and hickories. The chestnut trees are in bloom with fuzzy spikes of creamy white, and bumblebees heavy with pollen move among them. I tell the man what I see, and he smiles.

"When I was your age, that crack was so narrow, all I could see was a single little sapling on the forest floor," he says. "I've been chipping away at it all my life. Maybe your generation will be the one to finally reach the other side."

Hope is a great work that takes a lifetime. It is the hardest thing we are asked to do, and the most essential.

I am trying to show you a glimpse of the other side. Do you see it too?

#american chestnut#hope#climate change#biodiversity crisis#climate crisis#trees#plantarchy#learning to imagine the future

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

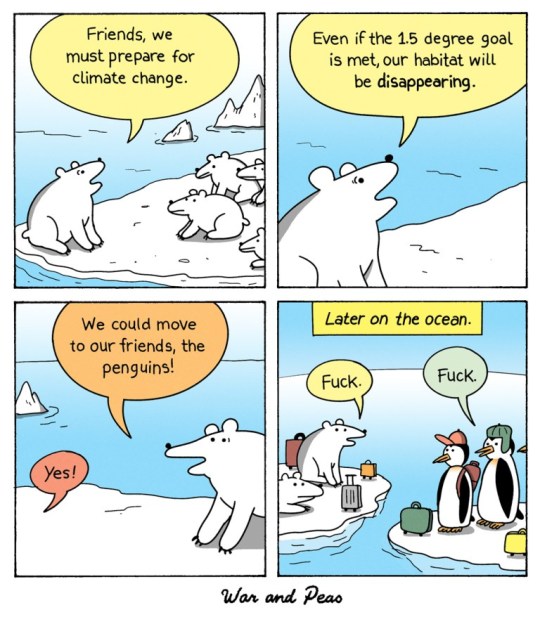

Move

New comic! “Move” is one of a series of climate comics that bring art and science together to explore the big questions about the climate crisis. More to read & download at https://www.comicartfestival.com/constrain-climate-comics

The other artists involved are – award-winning comic creator Darryl Cunningham and comic creator, academic and illustrator Sayra Begum.

CONSTRAIN is a 4-year programme…

View On WordPress

#biodiversity crisis#black humor#climate change#ClimateArt#ClimateChange#ClimateComics#ClimateCrisis#ClimateEmergency#Collab#comic#comic strip#ComicArt#comics#COP28#Creative Concern#dark humor#funny#humor#ice floe#north pole#ocean#penguin#penguins#polar bear#polar bears#polarbear#south pole#war and peas#webcomic#webcomics

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

caring about things is good actually

241 notes

·

View notes

Link

We have close to hundred milkweed plants growing on our property. I noticed yesterday that a lot of the leaves have serious gnaw marks, telling me that the monarch caterpillar has been visiting. Then today, I saw three monarchs flitting around the yard near the milkweed. It takes steps like these, ordinary people doing ordinary things, to save species rather than waiting for the bureaucrats of the US Government to do their jobs.

Excerpt from this story from the Washington Post:

The migratory monarch butterfly, a North American icon with a continent-spanning annual journey, now faces the threat of extinction, according to a top wildlife monitoring group.

Thursday’s decision by the International Union for Conservation of Nature to declare the species endangered comes as years of habitat destruction and rising temperatures have decimated the fluttering orange itinerants’ population.

The species’ numbers have dropped between 22 and 72 percent over the past decade, according to the new assessment. Monarchs in the Western United States are in particular danger: The population declined by an estimated 99.9 percent, from as many as 10 million butterflies in the 1980s to fewer than 2,000 in 2021.

“It is difficult to watch monarch butterflies and their extraordinary migration teeter on the edge of collapse, but there are signs of hope,” said Anna Walker, an entomologist at the New Mexico BioPark Society who led the butterfly assessment.

The loss of monarchs underscores a looming extinction crisis worldwide, with profound implications for the humans who have caused it. One million species could disappear, according to the United Nations, a potential calamity not just for plants and animals but also for the people who depend on ecosystems for food and fresh water.

The IUCN is a network of governmental and nonprofit organizations that comprehensively tracks the status of species. Scientists from around the world work together to produce assessments.

Among butterflies, the monarch is not alone. Butterflies across the West are vanishing as the region gets hotter and drier. According to one recent study, a majority of 450 species across a swath of 11 Western states are dropping in numbers.

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Get solar panels, get energy efficient retrofitting, get low flush toilets, get LED lights, take the #bus or get an electric car if you really can’t afford to not drive. Only buy what you really, really need. Live in a small home. Live in an apartment if you can. Don’t eat meat. Buy stuff with less plastic packaging. Reuse whatever you can. And most of all, work to destroy capitalism and colonialism. Get a tankless water heater. Get an electric stove. Keep the heating and the air conditioning in your home low. Pick up litter. Use active transportation like walking when you can. Don’t buy acrylic clothes. Buy less, buy less, buy less. Use reusable bottles, cups, plates, bowls, utensils, straws, containers, bags. Wear clothes until you can’t. Don’t buy any clothes you don’t need. I haven’t bought clothes in 8 years. Buy local food. Plant trees. Recycle. And most of all, work to destroy capitalism and colonialism.

#capitalism#climate crisis#climate#climate change#climate activism#climate and environment#climate emergency#climate hope#climate solutions#environmental issues#environnement#environmental activism#enviromental#biodiversity#biodiversity crisis#ecology#conservation#ecosystems#environment#action#change

17 notes

·

View notes

Text

(source: bbc news | 23 may 2023)

Almost half of the earth's animal species are currently declining, according to research led by Queen's University Belfast (QUB). The research has been published in the Biological Reviews journal,

The study examined population densities of more than 70,000 animals and researchers say it is the most comprehensive record to date.

It found 48% of species on earth are currently undergoing population declines, with less than 3% increasing.

It warns that global erosion of biodiversity caused by human industrialisation is "significantly more alarming" than previously thought.

The study describes the biodiversity crisis as one of "the most pressing challenges to humanity for the coming decades" that threatens the functioning of ecosystems life depends on, the spread of diseases and the stability of the global economy.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Celebrate the Green Marvels on International Plant Appreciation Day!

April 13 marks a day dedicated to the silent superheroes of our planet – plants. These green wonders not only provide us with the air we breathe and the food we eat but also contribute to the vibrant landscapes we love. International Plant Appreciation Day is a reminder to honor the unsung heroes of our ecosystem.

One extraordinary figure who understood the significance of plants was Richard St.…

View On WordPress

#2024#animals#April 13#April 26 – April 29#April 30 – May 5#biodiversity#biodiversity crisis#BirdLife#birds#celebration#changes#City Nature Challenge#conservationist#decline#document#Earth#Ecosystem#forests#Friends of the Saskatoon Afforestation Areas#fungi#George Genereux Urban REgional Park#global#green marvels#health#humanitarian#insects#interconnected#INTERNATIONAL PLANT APPRECIATION DAY#invasive#landscapes

0 notes

Text

France to set aside 10 per cent of its territory for biodiversity protection

On Monday, Prime Minister Elisabeth Borne unveiled a new 2030 Biodiversity Strategy under which France will put 10 per cent of its territory under “robust protection” to halt the gradual destruction of plant and animal life, Euractiv reports.

The strategy, which has been awaited for two years, includes a number of measures to protect and restore natural terrestrial and marine areas. Borne announced:

The collapse of living things is an existential threat to our societies. To stem it and reverse the trend, we are adopting a national biodiversity strategy for 2030. Our ambition is clear: to anchor the ecological transition in everyday life.

The strategy builds on the EU’s 2030 Biodiversity Strategy, which calls for effective protection of 30 per cent of land and oceans, restoration of 30 per cent of degraded ecosystems and a 50 per cent reduction in pesticide use, and the Kunming-Montreal agreement reached at COP15 on biodiversity in December.

Read more HERE

#world news#world politics#news#european news#europe#european union#eu politics#eu news#france news#france#biodiversity#biodiversity loss#biodiversity conservation#biodiversity crisis#ecosystems#ecology#environment#conservation#soil

0 notes

Text

Why a shrinking human population is a good thing

Why a shrinking human population is a good thing

The other day I was asked to do an interview for a South Korean radio station about the declining-population “crisis”.

Therein lies the rub — there is no crisis.

While I think the interview went well (you can listen to it here), I didn’t have ample time to flesh out my arguments; I’ve decided to put them down in more detail here.

Probably the most important aspect that I didn’t even get a…

View On WordPress

#age#ageing population#ageing population crisis#biodiversity crisis#climate change#consumption#dependency ratio#extinction crisis#immigration#quality of life#refugees#shrinking population#wealth#xenophobia

0 notes

Text

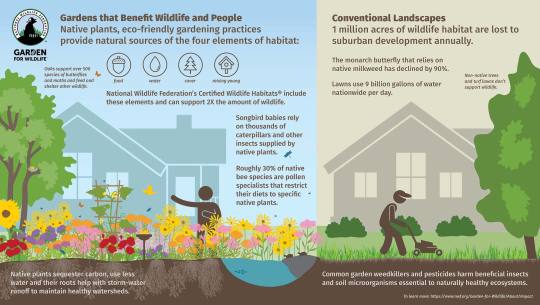

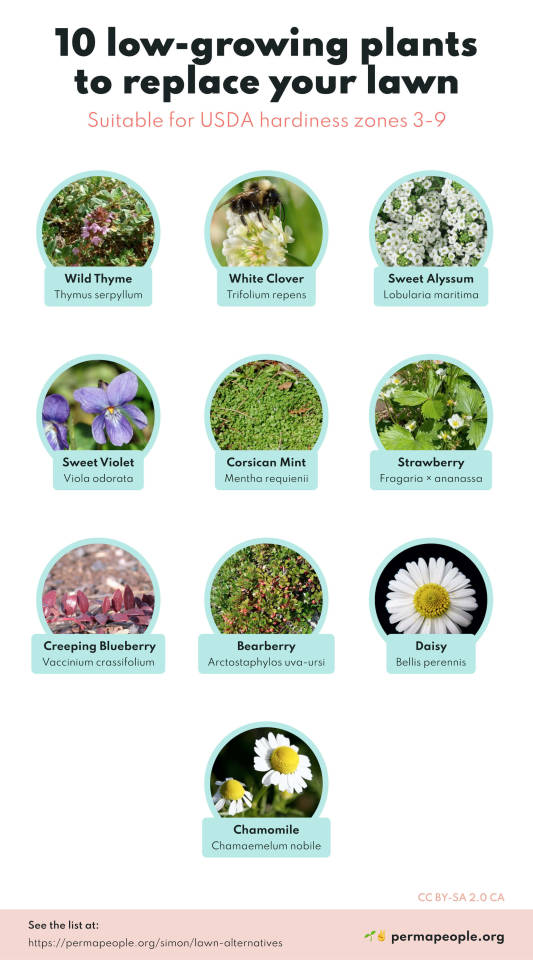

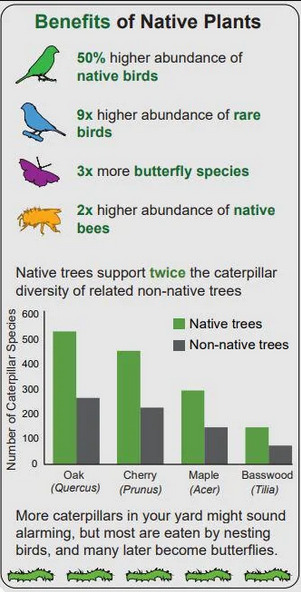

*casually posts this at the same time to further my agenda of growing native plants instead of grass and shitty ornamentals*

#gardening#water conservation#biodiversity#kill your lawn#native plants#native pollinators#pollinator garden#climate change#sustainability#environmental rehabilitation#habitat restoration#wildflowers#native flowers#animals#water crisis#didnt mean to post that grass one whoops. i think i skimmed it and wasnt thinking about it too much#but ig its true grass would be better than roads. lets just uh. make it native grass yaknow?

241 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here is an AMAZING piece on Solarpunk, it's abilities, and how it applies to our world written by Dr. Spencer Scott. I got to meet Spencer and his husband at their farm Solarpunk Farms in January of this year, and that experience is still something I hold super close to my heart. Highly recommend this reading, as well as everything else he's written, 10/10. You don't have to subscribe to solarpunk to enjoy it!

72 notes

·

View notes

Note

weird question, but do you know if regenerative agriculture is growing, and by what rate? it's important to me but looking for articles on my own can trigger a panic attack :[ no worries if not !

Hey! Thank you so much for asking. Honestly, agriculture and sustainable agriculture specifically are very close to my heart as well, so I was glad for the excuse to do some research :)

Also, thank you for your patience, I know you sent this Ask a bit ago. It’s good that you’re listening to yourself and not going around searching for things that might cause you harm, so thanks again for reaching out!

So, what is regenerative agriculture?

Regenerative agriculture is a way of farming that focuses on soil health. When soil is healthy, it produces more food and nutrition, stores more carbon and increases biodiversity – the variety of species. Healthy soil supports other water, land and air environments and ecosystems through natural processes including water drainage and pollination – the fertilization of plants.

Regenerative agriculture is a defining term for sustainability in our food system - while there is no one true definition of regenerative agriculture, the concept has been around for centuries, taking root in Indigenous growing practices. Regenerative approaches can bolster soil health and watershed health. They can also add to climate mitigation and potentially tie into regulatory or commercial incentives for a more sustainable diet.

Regenerative farming methods include minimizing the ploughing of land. This keeps CO2 in the soil, improves its water absorbency and leaves vital fungal communities in the earth undisturbed.

Rotating crops to vary the types of crop planted improves biodiversity, while using animal manure and compost helps to return nutrients to the soil.

Continuously grazing animals on the same piece of land can also degrade soil, explains the Regenerative agriculture in Europe report from the European Academies’ Science Advisory Council. So regenerative agriculture methods include moving grazing animals to different pastures.

How can it help?

Regenerative farming can improve crop yields – the volume of crops produced – by improving the health of soil and its ability to retain water, as well as reducing soil erosion. If regenerative farming was implemented in Africa, crop yields could rise 13% by 2040 and up to 40% in the future, according to a Regenerative Farming in Africa report by conservation organization the International Union for Conservation of Nature and the UN.

Regenerative farming can also reduce emissions from agriculture and turn the croplands and pastures, which cover up to 40% of Earth’s ice-free land area, into carbon sinks. These are environments that naturally absorb CO2 from the atmosphere, according to climate solutions organization Project Drawdown.

5 ways to scale regenerative agriculture:

1. Agree on common metrics for environmental outcomes. Today, there are many disparate efforts to define and measure environmental outcomes. We must move to a set of metrics adopted by the whole food industry, making it easier for farmers to adjust their practices and for positive changes to be rewarded.

2. Build farmers’ income from environmental outcomes such as carbon reduction and removal. We need a well-functioning market with a credible system of payments for environmental outcomes, trusted by buyers and sellers, that creates a new, durable, income stream for farmers.

3. Create mechanisms to share the cost of transition with farmers. Today, all the risk and cost sits with the farmers.

4. Ensure government policy enables and rewards farmers for transition. Too many government policies are in fact supporting the status quo of farming. The food sector must come together and work jointly with regulators to address this.

5. Develop new sourcing models to spread the cost of transition. We must move from sourcing models that take crops from anywhere to models that involve collaboration between off-takers from different sectors to take crops from areas converting to regenerative farming.

The rise of regenerative agriculture

In 2019, General Mills, the manufacturer of Cheerios, Yoplait and Annie’s Mac and Cheese (among other products), announced it would begin sourcing a portion of its corn, wheat, dairy and sugar from farmers who were engaged in regenerative agriculture practices and committed to advancing the practice of regenerative agriculture on one million acres of land by 2030. In early 2020, Whole Foods announced regenerative agriculture would be the No. 1 food trend and, in spite of the pandemic and the rapid growth of online shopping overshadowing the trend, business interest in the field still spiked by 138%.

More recently, PepsiCo announced it was adopting regenerative agriculture practices among 7 million acres of its farmland. Cargill declared it intends to do the same on 10 million acres by 2030, and Walmart has committed to advancing the practice on 50 million acres. Other companies pursuing regenerative agriculture include Danone, Unilever, Hormel, Target and Land O’ Lakes.

According to Nielsen, 75% of millennials are altering their buying habits with the environment in mind. This sentiment, of course, does not always materialize into tangible actions on behalf of every consumer. However, it is clear from the actions of PepsiCo, General Mills, Walmart, Unilever and others that they believe consumers’ expectations of what is environmentally friendly are shifting and that they will soon be looking to purchase regeneratively-produced foods because of the many benefits they produce.

The next step in the transition to regenerative agriculture is certification. The goal is to create labeling that will allow the consumer to connect to the full suite of their values. Some companies are partnering with nonprofit conveners and certifiers. The Savory Institute is one such partner, convening producers and brands around regenerative agriculture and more holistic land management practices.

In 2020, the Savory Institute granted its first “Ecological OutCome Verification (EOV) seal to Epic’s latest high protein bars by certifying that its featured beef was raised with regenerative agriculture practices.

The program was developed to let the land speak for itself by showing improvement through both leading and lagging functions such as plant diversity and water holding capacity. There are now thousands of products that have been Land to Market verified, with over 80 brand partnerships with companies such as Epic Provisions, Eileen Fisher and Applegate. Daily Harvest is giving growers in that space three-year contracts as well as markets and price premiums for the transitional crop. It's focusing on that transitional organic process as a stepping stone toward a regenerative organic food system.

Daily Harvest’s Almond Project creates an alliance with the Savory Institute and a group of stakeholders - including Simple Mills and Cappello’s - to bring regenerative practices to almonds in the Central Valley of California.

These companies are working with Treehouse California Almonds, their shared almond supplier, to lead soil health research on 160 acres of farmland. Over five years, the Project will focus on measuring outcomes around the ecosystem and soil health of regenerative practices – comparing those side by side with neighboring conventional baselines.

“We need industry partnership; we need pre-competitive collaboration,” says Rebecca Gildiner, Director of Sustainability at Daily Harvest, of the Almond Project. “Sustainability cannot be competitive. We are all sharing suppliers, we are all sharing supply – rising tides truly lift all boats. The industry has to understand our responsibility in investing, where historically investments have disproportionately focused on yields with a sole focus of feeding the world. We know this has been critical in the past but it has overlooked other forms of capital, other than financial. We need to look towards experimenting in holistic systems that have other outcomes than yield and profit - instead of saying organic can’t feed the world, we have to invest in figuring out how organic can feed the world because it’s critical.”

////

In short!!!

Many articles are stating regenerative agriculture as a defining, and rising “buzz word” in the industry. It seems that consumers are becoming more and more aware and are demanding more sustainable approaches to agriculture.

We, of course, have a way to go, but it seems from the data that I’ve gathered, that regenerative agriculture is, in fact, on the rise. Demand is rising, and many are working on ways to globalize those methods.

Source Source Source Source

#climate change#climate#hope#good news#climate news#climate crisis#more to come#climate emergency#news#climate justice#agriculture#ecosystem#farming#conservation#biodiversity#regenerative agriculture

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

Elon being a bit too honest about billionaires planning to exploit earth’s natural resources till all the birds go extinct….and then presumably escape to Mars

#billionaires hate birds#billionaires are an invasive species#eat the rich#anti capitalism#after seeing how the deep ocean deals with billionaires I’d like to let space have a turn#please Elon be on this first ship to mars#twitter implosion#wtf is x?#holy shit this man is so dumb#biodiversity loss#climate crisis#wtf is going on man for real

78 notes

·

View notes

Link

A few days ago, I posted a link to a New York Times story about the latest version of the Living Planet Index, which is the subject of this story from Treehugger. (I also reblogged an essay about the index and the biodiversity crisis from Bill McKibben.) I regret the posting of the New York Times story, because the journalists who wrote the story were seriously downplaying the severity of the conclusions made by the scientists behind the Living Planet Index. What was I thinking? Dunno, fell into the media trap? Here’s an excerpt from a more accurate review of the Index from Treehugger:

“Today we face the double, interlinked emergencies of human-induced climate change and the loss of biodiversity, threatening the well-being of current and future generations.”

So begins the executive summary of the Living Planet Report 2022. Released every two years by the World Wildlife Fund (WWF), the study examines global biodiversity and the health of the planet. The latest report reveals an average 69% drop in world vertebrate species in less than 50 years.

The report considers nearly 32,000 populations of 5,230 species from the Living Planet Index (LPI). Provided by the Zoological Society of London, the index tracks trends in species abundance around the world. This year’s report includes data on more than 838 new species and 11,000 new populations since the last report was released in 2020.

In addition to putting numbers to species declines, the report shows the threats behind those drops, how these statistics relate to planetary health, and offers possible solutions.

The report details the connection between climate change and biodiversity loss and focuses on some species that have plummeted, as well as some that have rebounded.

For example:

There was an estimated 80% plunge in the population of eastern lowland gorillas in the Kahuzi-Biega National Park in the Democratic Republic of Congo between 1994 and 2019. The main threat to the species, also known as Grauer’s gorilla, is hunting.

Hunting was one of the main causes of the 64% decline in Australian sea lion pups in South and Western Australia between 1977 and 2019. The pups are also often caught in fishing gear and die from diseases.

But there have been some promising discoveries with species that have been recovering.

The population of loggerhead turtle nests grew by 500% on the coast of Chrysochou Bay in Cyprus from 1999 to 2015. Credit conservation efforts that include relocating nests and using cages to protect others from predators.

Conservation measures have also helped mountain gorillas. In the Virunga Mountains along the northern border of Rwanda, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Uganda, populations of mountain gorillas increased to 604 animals, up from 480 gorillas in 2010.

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

One of Brazil's top scientists, Eneas Salati, once said, "The best thing you could do for the Amazon rainforest is to blow up all the roads." He wasn't joking. And he had a point.

In an article published in Nature, my colleagues and I show that illicit, often out-of-control road building is imperiling forests in Indonesia, Malaysia and Papua New Guinea. The roads we're studying do not appear on legitimate maps. We call them "ghost roads."

What's so bad about a road? A road means access. Once roads are bulldozed into rainforests, illegal loggers, miners, poachers and landgrabbers arrive. Once they get access, they can destroy forests, harm native ecosystems and even drive out or kill indigenous peoples. This looting of the natural world robs cash-strapped nations of valuable natural resources. Indonesia, for instance, loses around A$1.5 billion each year solely to timber theft.

All nations have some unmapped or unofficial roads, but the situation is especially bad in biodiversity-rich developing nations, where roads are proliferating at the fastest pace in human history.

continue reading

#world#tropical rainforests#deforestation#biodiversity loss#ghost roads#timber theft#environment#climate crisis

12 notes

·

View notes