#borobudur

Text

Often described as the world’s largest Buddhist monument, Borobudur rises from the jungles of central Java: a nine-leveled step pyramid decorated with hundreds of Buddha statues and more than 2,000 carved stone relief panels. Completed in 835 AD by Buddhist monarchs who were repurposing an earlier Hindu structure, Borobudur was erected as “a testament to the greatness of Buddhism and the king who built it,” says religion scholar and Borobudur expert Uday Dokras.

Though Buddhists make up less than one percent of Indonesia’s population today, Borobudur still functions as a holy site of pilgrimage, as well as a popular tourist destination. But for the Indonesian Gastronomy Community (IGC), a nonprofit organization dedicated to preserving and celebrating Indonesian food culture, Borobudur is “not just a temple that people can visit,” says IGC chair Ria Musiawan. The structure’s meticulous relief carvings, which depict scenes of daily life for all levels of ninth-century Javanese society, provide a vital source of information about the people who created it. Borobudur can tell us how the inhabitants of Java’s ancient Mataram kingdom lived, worked, worshiped, and—as the IGC demonstrated in an event series that ended in 2023—ate.

The IGC sees food as a way to unite Indonesians, but the organization also considers international gastrodiplomacy as a part of their mission. Globally, Indonesian food is less well-known than other Southeast Asian cuisines, but the country’s government has recently made efforts to boost its reputation, declaring not one, but five official national dishes in 2018. To promote Indonesian cuisine, the IGC organizes online and in-person events based around both modern and historical Indonesian food. In 2022, they launched an educational series entitled Gastronosia: From Borobudur to the World. The first event in the series was a virtual talk, but subsequent dates included in-person dinners, with a menu inspired by the reliefs of Borobudur and written inscriptions from contemporary Javanese sites.

In collaboration with Indonesia’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs and other partner organizations, the first meal in the Gastronosia series was, fittingly, held at Borobudur, with a small group of guests. The largest event, which hosted 100 guests at the National Museum in Jakarta, aimed to recreate a type of ancient royal feast known as a Mahamangsa in Old Javanese, meaning “the food of kings.” The IGC’s Mahamangsa appeared alongside a multimedia museum exhibition, with video screens depicting the art of ancient Mataram that inspired the menu and displays of historical cooking tools, such as woven baskets for winnowing and steaming rice. Another event, held at Kembang Goela Restaurant, featured more than 50 international ambassadors and diplomats invited by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

But how does one translate 1,000-year-old stone carvings into a modern menu that’s not only historically accurate, but appetizing? “We have to have this very wide imagination,” says Musiawan. “You only see the relief [depicting] the food…but you cannot find out how it tastes.” The IGC designed and tested a Gastronosia menu with the help of Chef Sumartoyo of Bale Raos Restaurant in Yogyakarta, and Riris Purbasari, an archaeologist from the Central Java Province Cultural Heritage Preservation Center, who had been researching the food of Borobudur’s reliefs since 2017.

The range of human activities depicted in the reliefs of Borobudur is so wide that it has inspired research in areas of study stretching from music to weaponry. There have even been seaworthy reconstructions based on the “Borobudur Ships” displayed on the site’s lower levels, exquisitely rendered vessels like the ones that facilitated trade in ancient Southeast Asia. So it’s no surprise that Borobudur has no shortage of depictions of food-related scenes, from village agricultural labor, to the splendor of a royal Mahamangsa, to a bustling urban marketplace. Baskets of tropical fruit, nets full of fish, and even some modern Indonesian dishes are recognizable in the reliefs, such as tumpeng, a tall cone of rice surrounded by side dishes, which is still prepared for special occasions. Some images are allegories for Buddhist concepts, providing what Borobudur archaeologist John Mikic called “a visual aid for teaching a gentle philosophy of life." Uday Dokras suggests that these diverse scenes might have been chosen to help ancient visitors “identify with their own life,” making the monument’s unique religious messaging relatable. The reliefs illustrate ascending levels of enlightenment, so that visitors walk the path of life outlined by the Buddha’s teachings: from a turbulent world ruled by earthly desires at the lowest level, to tranquil nirvana at the summit.

Musiawan says that the IGC research team combined information from Borobudur with inscriptions from other Javanese sites of the same era that referenced royal banquets. While Borobudur’s reliefs show activities like farming, hunting, fishing, and dining, fine details of the food on plates or in baskets can be difficult to make out, especially since the painted plaster that originally covered the stone has long-since faded. Ninth-century court records etched into copper sheets or stone for posterity—some accidentally uncovered by modern construction projects—helped fill in the blanks when it came to what exactly people were eating. These inscriptions describe the royal banquets of ancient Mataram as huge events: One that served as a key inspiration for the IGC featured 57 sacks of rice, six water buffalo, and 100 chickens. There are no known written recipes from the era, but some writings provide enough detail for dishes to be approximated, such as freshwater eel “grilled with sweet spices” or ground buffalo meatballs seasoned with “a touch of sweetness,” in the words of the inscriptions, both of which were served at Gastronosia events.

Sugar appears to have been an important component in ancient Mataram’s royal feasts: A survey of food mentions across Old Javanese royal inscriptions revealed 34 kinds of sweets out of 107 named dishes. Gastronosia’s Mahamangsa ended with dwadal, a sticky palm-sugar toffee known as dodol in modern Indonesian, and an array of tropical fruits native to Java such as jackfruit and durian. Other dishes recreated by the IGC included catfish stewed in coconut milk, stir-fried banana-tree core, and kinca, an ancient alcohol made from fermented tamarind, which was offered alongside juice from the lychee-like toddy palm fruit as an alcohol-free option.

Musiawan describes the hunting of animals such as deer, boar, and water buffalo as an important source of meat in ninth-century Java. Domestic cattle were not eaten, she explains, because the people of ancient Mataram “believed that cows have religious value.” While Gastronosia’s events served wild game and foraged wild greens, rice also featured prominently, a key staple in Mataram that forms the subject of several of Borobudur’s reliefs. It was the mastery of rice cultivation that allowed Mataram to support a large population and become a regional power in ninth-century Southeast Asia. Rice’s importance as a staple crop also led to its inclusion in religious rituals; Dokras explains that in many regions of Asia, rice is still an essential component of the Buddhist temple offerings known as prasad.

The indigenous Southeast Asian ingredients used in Gastronosia’s Mahamangsa included some still widely-popular today, such as coconut, alongside others that have fallen into obscurity, like the water plant genjer or “yellow velvetleaf.” Musiawan acknowledges that modern diners might find some reconstructed ancient dishes “very, very simple” compared to what they’re used to “because of many ingredients we have [now] that weren’t there before.” But in other cases, ninth-century chefs were able to achieve similar flavors to modern Indonesian food by using their own native ingredients. Spiciness is a notable example. Today, chillies are near-ubiquitous in Indonesian cuisine, and Java is especially known for its sambal, a spicy relish-like condiment that combines pounded chillies with shallots, garlic, and other ingredients. But in ancient Mataram, sambal was made with native hot spices, such as several kinds of ginger; andaliman, a dried tree-berry with a mouth-numbing effect like the related Sichuan pepper; and cabya or Javanese long pepper. “It tastes different than the chili now,” Musiawan says of cabya, “but it gives the same hot sensation.” Chillies, introduced in the early modern era by European traders, are still called cabai in Indonesian, a name derived from the native cabya they supplanted.

Gastronosia is just the beginning of IGC’s plans to explore Indonesian food history through interactive events. Next, they intend to do a series on the food of ancient Bali. By delving into the historic roots of dishes Indonesians know and love, the IGC hopes to get both Indonesians and foreigners curious about the country’s history, and dispel preconceptions about what life was like long ago. Musiawan says some guests didn’t expect to enjoy the diet of a ninth-century Javanese noble as much as they did. Before experiencing Gastronosia, she says, “They thought that the food couldn't be eaten.” But afterward, “They’re glad that, actually, it's very delicious.”

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Borobudur Temple, Central Java, Indonesia

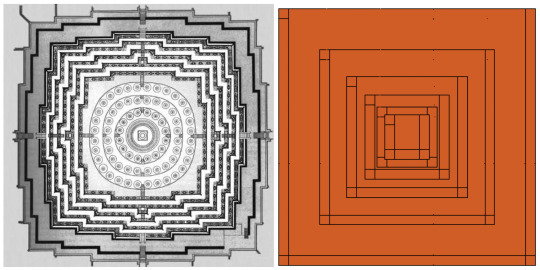

References: Google Maps, Borobudur was Built Algorithmically by Hokky Situngkir (Dept. Computational Sociology, Bandung Fe Institute Center for Complexity, Surya University)

“The mathematical study for Borobudur’s architectural design has once related to answer the question about the metric system used by ancient Javanese to build such giant buildings with good measurement. While the anthropological revealed that Javanese used tala system (metric system with length measurement defined as the length of a human face from the forehead's hairline to the tip of the chin or the distance from the tip of the thumb to the tip of the middle finger when both fingers are stretched at their maximum distance), the survey as elaborated in Atmadi (1988) showed there is a ratio used between parts of Borobudur. There is part of Head : Body: Foot (9 : 6 : 4) that is met in horizontal and vertical measurement of the temple.”

—Hokky Situngkir, Borobudur was Built Algorithmically

#quote#architecture#Buddhism#Buddhist architecture#stupa#Indonesia#geometry#Borobudur Temple#Borobudur#metric system#human body#math#mathematics#architectural theory#Java#Javanese architecture

181 notes

·

View notes

Text

@anannt_urjaa

Borobudur, Indonesia

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

🫶 Borobudur Temple, Indonesia 🇮🇩❤️🤍

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Borobudur #15, Indonesia, 1996, © Kenro Izu, Courtesy of Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Borobudur temple in Central Java, Indonesia

Dutch vintage postcard, mailed in 1910 to The Hague, Netherlands

#old#postcard#postkaart#hague#indonesia#java#vintage#the hague#briefkaart#postal#1910#ansichtskarte#temple#ephemera#photography#photo#postkarte#tarjeta#borobudur#mailed#central#dutch#central java#historic#sepia#netherlands#carte postale

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

[Photo above: as if it were reminiscent of UFOs, Great Buddhist Temple in Borobudur, Indonesia]

The Quest for Buddhism (95)

Buddhist cosmology

Spatial cosmology

The Buddhist spatial cosmology displays the various worlds in which beings can be reborn. Spatial cosmology can also be divided into two branches. The vertical (or cakravada; devanagari) cosmology describes the arrangement of worlds in a vertical pattern, some being higher and some lower. By contrast, the horizontal (sahasra) describes the grouping of these vertical worlds into sets of thousands, millions or billions. A ‘sahasra’ is a Vedic measure of count data, means "one thousand".

[Photo above: The whole view of Borobudur, a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Central Java, Indonesia.]

仏教の探求 (95)

仏教の宇宙論

空間的宇宙論について

仏教における空間的宇宙論とは、生物が生まれ変わることができる様々な世界を表示する。空間宇宙論はまた、2つの枝に分けることができる。垂直 (チャクラヴァーダ: デーヴァナーガリー) 宇宙論の宇宙空間は、ある世界は高く、ある世界は低くというように、世界が垂直に配置されていることを説明するものである。これに対して、水平 (サハスラ) 宇宙論は、これらの垂直な世界を数千、数百万、数十億の集合にグループ化したものである。サハスラとは、ヴェーダの計数データの尺度で、「千」を意味する。

#buddhist cosmology#spatial cosmology#buddhism#buddha#borobudur#vertical cosmology#horizontal cosmology#karma#sahasra#universe#ufo#history#philosophy#nature#art

109 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ancient temple with a Dielectric Resonator Antenna. (They insulate as well as osculate) This holds frequency better than any metal modern counterpart.

Borobudur is a temple that took over 100 years to build, from the time of Rakai Mataram Ratu Sanjaya (717-745) until it was completed in 825 and inaugurated during the reign of Sri Maharaja Samarottungga (782-835)

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Tranquility

A simple moc on Buddha minifigure at beautiful Borobudur, Indonesia

#tranquility#serenity#calm morning#sunrise#borobudur#buddha#siddhārtha gautama#gautama buddha#beautifulindonesia#yogyakarta#legomoc#legophotography#fujifilm#toyartistry#artists on tumblr#brickcentral#reflection#epictoyart#fujifilm x series#legominifigures#minifigures#sooc#minimalism#toypictures#toypic community#raw community#legoart#stilllifephotography#rawart

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

A meditative Buddha statue perform dharmachakra mudra hand gesture inside the perforated bell-shaped stupa on upper platform of Arupadhatu in Borobudur.

3 notes

·

View notes

Video

Indonesia marks Vesak with flying lanterns over Borobudur temple

VIDEO: Hundreds of lanterns were released into the sky by Indonesian Buddhists celebrating Vesak day at the temple of Borobudur for the first time since the coronavirus pandemic hit the country.

(via Twitter: AFP News Agency @AFP)

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

Perjalanan Bhikku dari Thailand menuju Candi Borobudur Indonesia

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

• CONGRATULATIONS • Your photo was chosen for us to repost ------------------------------------------ The best photo from IG @w_yomoto • • • • • • Borobudur, Jawa Tengah, Indonesia Pembuat gula aren tradisonal #sugar #traditional #humaninterestphotography #_humaninterest #canonindonesia #canonasia #canonid #humanity_shots #borobudur #travelphotography ------------------------------------------ Jangan lupa follow dan tag instagram @_humaninterest di foto yang kamu upload Gunakan hastag #_humaninterest Bila ada kritik atau saran silahkan tulis di kolom komentar atau DM ------------------------------------------ https://www.instagram.com/p/CjmypKkvXpC/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

#sugar#traditional#humaninterestphotography#_humaninterest#canonindonesia#canonasia#canonid#humanity_shots#borobudur#travelphotography

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

☀ "VHWÃNĀ ÇHAKA PHALĀ" ☀

✨ Sanghãramā Mãha Thupã Aryā Mahãvihariyā Para Therrā, Vhwãnā Çhaka Phalā ✨

1. Nama Asli Candi Tersebut, Bukan Borobudur. Nama Karangan (Bore-Budur) Itu DiCiptakan Oleh Thomas Stamford Raffles (1814).

2. Nama Asli Candi Tersebut Adalah : "Sanghăramā Măha Thupă Aryā, Mahăvihariyā Para Therrā, Vhwănā Çhaķâ Phalā".

3. Candi Tersebut BUKAN CANDI BUDDHA. Tapi Asli Ajaran Dharma Nuswantara (Bangsa Çhaķâ / Arya), Sumber Asli Yang Di Kemudian Hari Melahirkan Ajaran Hindu (Sanatha Dharma/Vedantist) & Ajaran Buddha Di JambuDvipa / India.

4. Candi Tersebut BUKAN DIBANGUN OLEH DINASTI WANGSA SYAILENDRA, Apalagi Oleh Bangsa-Bangsa Yang Hidup Di Masa Mereka Itu.

5. Usia Candi Tersebut Jauh Lebih Tua Dari Perkiraan Para Arkeolog & Ahli Sejarah Mana Pun.

6. Candi Tersebut SENGAJA DITUTUPI, BUKAN TERTIMBUN Oleh Peristiwa Alamiah.

7. Candi Tersebut SENGAJA DITINGGALKAN TERTUTUP AKIBAT EKSPANSI DARI ARAH BHARAT DALAM JUMLAH BESAR, Agar Tidak (Seharusnya) DiTemukan Oleh Bangsa Yang DiKemudian Hari Mendiami Tanah Tersebut.

8. Keturunan Asli Bangsa Çhaķâ, BUKAN BANGSA JAWA TEMPORER YANG SEKARANG MENDIAMI Tanah Berdirinya Candi Tersebut.

9. Keturunan Asli Bangsa Çhaķâ, Memiliki Ciri Fisik Yaitu Struktur Tulang Yang Lebih Besar & Kokoh, Berkulit Cenderung Lebih Gelap & Bersinar, Rambut Kepala Yang Sama Persis Dengan Patung Di Dalam Setiap Stupa Di Candi Tersebut.

10. Rahasia Candi Tersebut HANYA AKAN TERUNGKAP, Setelah Suara Gemuruh Yang Menggelegar & DiTandai Dengan Lengkingan Garuda Yang Menetaskan Telur Dari Arah Seberang Timur Laut.

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

5 Nights / 6 Days Borobudur, Indonesia Tour Package

5 Nights / 6 Days Borobudur, Indonesia Tour Package

5 Nights / 6 Days #Borobudur, #Indonesia #TourPackage

Price based on minium 2 pax and subject to change without prior notice :

Grand Ambarrukmo 4* : USD 776 Per Person

Royal Ambarrukmo 5* : USD 834 Per Person

#Yogyakarta #BorobudurBuddhistTemple #MendutandPawonTemple #MegnificentSultanPalace #TamansariWaterCastle #SandDune #ParangtritisBeach #MerapiLavaTour #Bunker #BatuAlien…

View On WordPress

#Adler Tours#Adler Tours and Safaris#Asia#Batu Alien#Borobudur#Borobudur Buddhist Temple#Bunker#family Holidays#Gujarat#Holiday Packages#India#Indonesia#Jogja#Mangkunegaran Palace#Megnificent Sultan Palace#Mendut and Pawon Temple#Merapi Lava Tour#Museum Batik Danar Hadi#Museum Keris#Museum Sisa Hartaku#Parangtritis Beach#Plaosan Temple#Prambanan Temple#Rajkot#Sand Dune#Tamansari Water Castle#Tour Packages#Travel#Triwindu Flea Market#Yogyakarta

2 notes

·

View notes