#britons

Text

Wrote a really long post about the history of Britain and how that is brought up in the context of claims of 'nativeness' to these islands but not sure if people'd be interested in that.

If you would like to see that post interact with this post (either like or reblog) and I might be able to finish writing the original post and post it before this evening.

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

Samuel Rason, British model.

48 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who were the Dobunni tribe? From ancient coin-minters and guardians of tradition, they thrived through a peaceful way of life amidst the tumultuous backdrop of ancient Britain. But their idyllic, autonomous lifestyle ended with the arrival of the Romans.

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

I randomly slip into some sort of british/scottish/Welsh accent so much and it's NOT OKAY cuz people are like 'wtf you just say????'

This is why I need to move to Canada

#good omens#david tennant#michael sheen#micheal sheen#uk#Scottish#Scotland#British#Brit#Britons#Welsh#Wales#Canada#neil gaiman

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

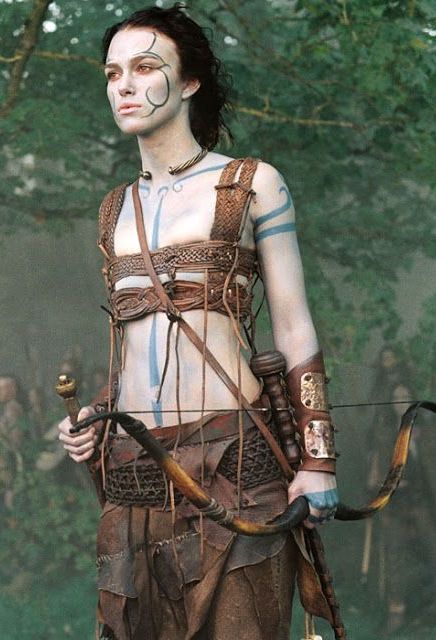

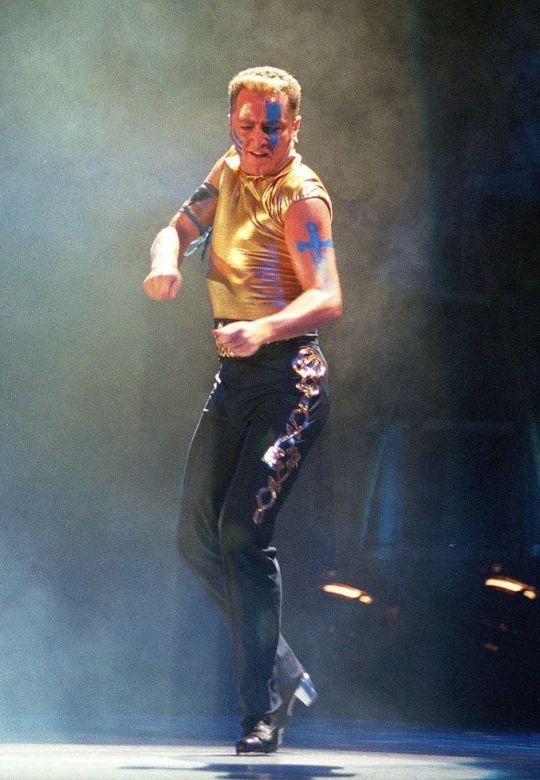

Should this Celt be blue?

An irish-dress-history game.

I've been researching the actual historical evidence behind the idea that ancient Insular Celts painted or tattooed themselves blue, and I thought it would be fun to make a game out of it. Below are various depictions of this idea along with the culture and date they are supposed to be depicting. The game is to guess whether each use of body paint or tattoos is supported by actual historical evidence. Answers are in the image descriptions.

(Note: This game is not intended to mock or criticize the artists and costume designers of any of these works. Good information on this topic is hard to find, and movie creators and artists frequently have goals other than historical accuracy. I am mocking Mel Gibson though, because f*** that guy.)

1 A 'Woad' (ie Pict) from 5th c. Britain. 2. Tattooed Irish warrior in 1170

3. A Medieval Scottish lord 4. Iceni Queen Boudica c. 60 CE

5. Ancient? Ireland 6. Britons during the time of Julius Cesar

7. Picts in 149 CE 8. Scots in 1297

Bibliography:

Hoecherl, M. (2016). Controlling Colours: Function and Meaning of Colour in the British Iron Age. Archaeopress Publishing LTD, Oxford. https://www.google.com/books/edition/Controlling_Colours/WRteEAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=0

MacQuarrie, Charles. (1997). Insular Celtic tattooing: History, myth and metaphor. Etudes Celtiques, 33, 159-189. https://doi.org/10.3406/ecelt.1997.2117

#iron age#roman era#early medieval#ancient celts#celtic#pict#tattoos#body painting#medieval#insular celts#gaelic irish#Hoecherl#brittonic celts#britons#gaels#scots

7 notes

·

View notes

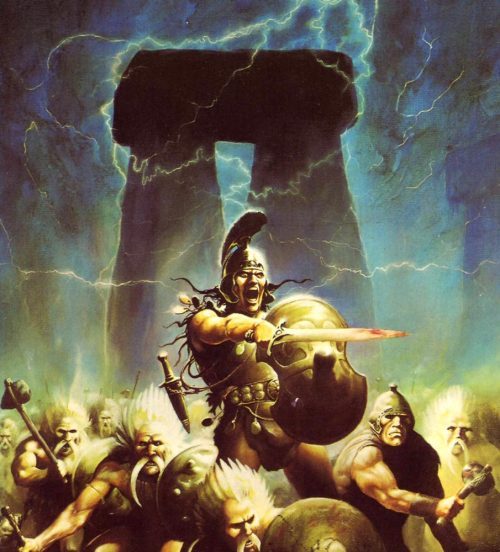

Photo

Melvyn Grant.

184 notes

·

View notes

Photo

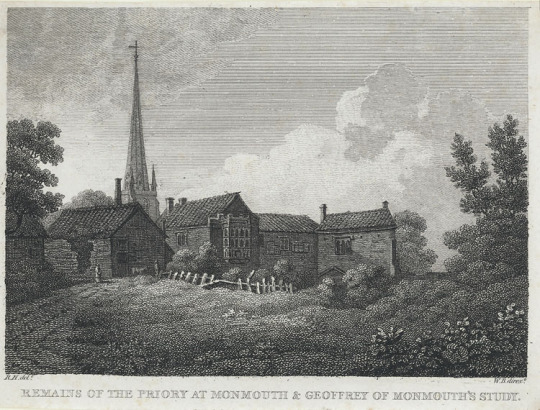

The Historical Value of Geoffrey of Monmouth

An Original Essay of Lucas Del Rio

The year was 1136. Britain in recent centuries had come to be defined by her English, Welsh, and Scottish boundaries. Of the three, England by far exercised the greatest hegemony. Most of the people living there talked in the English tongue, although the Norman leadership spoke French. This was because the population of England consisted mainly of the Anglo-Saxons, with their Norman-French overlords only recently having seized power. There had been a time, however, when the Saxons were the invaders, for they were not the indigenous people of the island. It was the story of Britain and her early history that the Welsh clergyman Geoffrey of Monmouth told in his 1136 work The History of the Kings of Britain.

Other British historians, including those of the present day and his own contemporaries, have tended to be highly critical of Geoffrey. His work, they say, is filled with myth. There is no doubt that there is a great deal of legend contained within its pages, although there are also reasons that the text deserves to be the subject of historical research. Many early history books filled in gaps of knowledge with legend, and the myths the medieval Welshman provides offer insight into the now largely forgotten traditional beliefs of the Celtic Britons. It is also the only surviving source to thoroughly explore the history of Britain prior to Roman occupation. Some of the episodes of British history from the Roman era and early Middle Ages touched on by other writers are discussed in far more detail by Geoffrey. Finally, his account of the life of King Arthur towards the end of the book is among the earliest sources for the Arthurian legend.

Geoffrey was aware that there were other writers of British history, but he felt that he could offer insight that others had not yet been able to do. “It has seemed a remarkable thing to me that, apart from such mention of them as Gildas and Bede had each made in a brilliant book about the subject, I have not been able to discover anything at all on the kings who lived here before the Incarnation of Christ, or indeed about Arthur and all the others who followed on after the Incarnation,” says Geoffrey as he opens his book. In this fragment of his opening statement, he is clearly giving praise to Gildas and the Venerable Bede, two historians who had lived centuries before his own time but whose works were highly respected. The first of these, published by the Romano-British monk Gildas in 540 AD, was On the Ruin and Conquest of Britain. When Gildas wrote, Roman occupation was still a fresh memory, and the withdrawal of Roman garrisons had left the Britons vulnerable to Germanic, Irish, and Pictish invaders. Gildas, in his book, writes a brief history of how the Romans had once subjugated the island and then how they had left. Later, the book consists of Gildas condemning the new kings who had emerged from the former Roman province. From his perspective, they were both sinful and had been unable to effectively respond to the challenges facing a post-Roman Britain.

The other British historian referenced by Geoffrey at the start of his book is the Venerable Bede, who wrote much later than Gildas but still a very long time before he himself wrote The History of the Kings of Britain. His chief work, and probably the one that Geoffrey is calling “a brilliant book,” was the 731 AD book Ecclesiastical History of the English People. As the title suggests, the primary focus of the book is the history of the church in English society. Along the way, Bede also chronicles the wars, cultural changes, and royal dynasties of the era. Ecclesiastical History of the English People is the oldest surviving comprehensive British history book, and one that was the gold standard for other British history books to emulate for much of the rest of the medieval era. Even today, it remains invaluable for the particular time period that it covers. Geoffrey obviously respected both him and the earlier Gildas, yet he saw certain weaknesses in works that did indeed have a great deal of merit. Britain in the era prior to the dawn of Christianity is almost entirely ignored by the two historians. Their chronicles of the early medieval era also are lacking in biographic information of the kings of the Celtic Britons. Gildas offers more criticism of leadership style than any real biographical detail, and Bede neglects the Britons in favor of the lives of Anglo-Saxon kings.

“The deeds of these men were such that they deserve to be praised for all time,” continues Geoffrey, making it clear that he is setting out to write a book that he feels deserves to exist. “These deeds were handed joyfully down in oral tradition,” he asserts, although he also claims to have used as a source “a certain very ancient book written in the British language.” Certainly, any history of the Britons written at this point which covered the span that it did would have had to make use of oral tradition. A trickier question is whether or not the “ancient book written in the British language” really existed. Prior to English becoming the dominant language, the Britons had spoken a language called Brythonic, which eventually branched into the modern Celtic dialects of Breton, Cornish, and Welsh. As someone who was Welsh, especially at a time when Wales was not yet as Anglicized as it would later become, it seems perfectly feasible that Geoffrey would have had knowledge of Brythonic. Modern knowledge of Brythonic is limited, but it may have been written in the Ogham alphabetic script that was at the time used by the Irish and the Picts. Geoffrey could, however, have simply been adding such a detail at the beginning of his book to capture the attention of his audience. Discovering an “ancient book” is more exciting than depending solely on oral tradition.

Geoffrey clearly made use of surviving sources whether or not he really had an “ancient book written in the British language.” Bede, whom Geoffrey highly respected despite perceiving certain shortcomings, was one. Both Ecclesiastical History of the English People and The History of the Kings of Britain start their chronicles by introducing the island of Britain herself, with very similar descriptions of her geography and natural resources. This opening of Bede must have been as influential on medieval British historians as the rest of his book, as it is also closely copied by Henry of Huntington, a contemporary of Geoffrey, in History of the English. Next, Geoffrey makes a statement that very much sets up a great deal of the rest of his book, which largely consists of the epic struggle of the Britons against hostile foreigners such as the Romans, Norwegians, and Irish. “Britain is inhabited by five races of people,” he says. Even though “the Britons once occupied the land from sea to sea,” he declares that “the vengeance of God overtook them because of their arrogance and they submitted to the Picts and the Saxons.”

The first tale told by Geoffrey is the one that is the most blatantly a legend, and also one that ties in closely with Greco-Roman mythology. In fact, Greco-Roman myth is a prominent theme for much of the book, with the early Britons described as worshiping their deities. Multiple explanations can be offered for this. For one, there was plenty of nostalgia in the Middle Ages for classical antiquity, which some medieval Europeans perceived to have been a more civilized time. However, perhaps a better explanation is that Celtic religion was assimilated into that of the Roman Empire when Celtic lands were conquered. Today, many aspects of Celtic religion are lost to history, and this may have been no less true at a time when Britain had already long been Christianized. It seems likely that all Geoffrey knew of the religion of the Celtic Britons was its eventual fusion with Roman elements. All of the references to classical mythology in the book align more closely with the Romans than with the Greeks. Roman names of the gods and goddesses are used, the book incorporates the story found in the Latin poem The Aeneid by Virgil, and the Greeks are portrayed as antagonists while the Trojans are glorified.

The story Geoffrey tells at the beginning of his narrative is also told to an extent in an older work from 833 AD called The History of the Britons. While the authorship of the work is disputed, and it may actually be a compilation of multiple authors over many years, The History of the Britons is commonly ascribed to the monk Nennius. Like The History of the Kings of Britain, the text attempts to chronicle history from the perspective of the Celtic Britons rather than the Anglo-Saxons who were writing the overwhelming majority of the accounts. Both books tell many of the same stories with some differences, although The History of the Britons is significantly shorter than the work penned by Geoffrey. At the start of both books, the reader is introduced to a great-grandson of the Trojan hero Aeneas by the name of Brutus. After accidentally killing his father, he is exiled from Italy and ultimately arrives in Britain. Apparently it was from him that the island took her name. This cannot be true, of course, because the term “Britain” originates with Greek explorers and was not used by native Britons prior to contact with Mediterranean peoples. Nennius, or whomever else may have written The History of the Britons, does not detail how Britain was populated. Nor does the book History of the English by Henry of Huntington, who also tells the story of Brutus.

For all the reader knows, Britain may already have had inhabitants, and Brutus may merely have become a person of prominence there. Geoffrey, on the other hand, tells a far more fanciful tale. In his book, the island “called Albion” when Brutus arrived “was uninhabited except for a few giants.” Accompanying Brutus to Albion were other descendants of those who had lived in Troy. After the Trojan War, Geoffrey tells his reader, the Greeks had enslaved their vanquished enemies. Brutus can be described as leading a revolutionary Exodus of sorts against an apparent “King of the Greeks.” Some modern readers may view such a term with skepticism, noting that Greece in antiquity was divided into numerous independent city-states. It should also be noted, however, that Greece was organized in this fashion during the archaic, classical, and hellenistic eras of Greek history. Much less is known of Greek society during the Bronze Age, when the Trojan War would have taken place, due to a total absence of literature. The Iliad by the legendary poet Homer describes Greek forces being commanded by an overlord named Agamemnon during the Trojan War.

Regardless of any other details of this section of the narrative, it is almost certainly fantasy. However, it has value in that it shows how the myths of the Britons meshed at some point with their Roman conquerors. As the story is told, albeit in much less detail, in The History of the Britons more than three hundred years earlier, Geoffrey cannot have simply made the whole thing up for entertainment value. Perhaps of greater interest to historical scholarship are the stories that immediately follow, which tell of a Celtic society in Britain prior to Roman subjugation. No written records exist from this era of British history, so a book preserving its oral traditions is invaluable. Some readers may be surprised by the tales of powerful kings, burgeoning towns, and massive wars, possibly meeting them with skepticism. It is nearly impossible to assess the accuracy of the stories, although they should not be dismissed. A common yet ignorant image of pre-Roman Britain is that it was barely emerging from the Stone Age, yet archaeology demonstrates otherwise. Trade goods have been unearthed from as far away as Egypt and Greece, and it should be remembered that the Celtic Britons managed to construct the magnificent monument now known as Stonehenge.

One of the first stories after the kingship of Brutus, and certainly one of interest, follows the partition of the island amongst his three sons. There are no quarrels between them, but they end up having to repel an invasion of the Huns. As the Huns did not invade Europe until the final decades of the Roman Empire, it is impossible that this exact circumstance could have taken place. It is a stretch to suggest the Huns even existed just a few generations after the Trojan War. However, there have been numerous nomadic peoples who have invaded different regions of Europe at various points in history. A horde similar to the one led back Attila could feasibly have built boats and sailed to Britain, and they may simply have been remembered later by a familiar name. On the other hand, the ravages of the Huns in Europe could have created a legend that they had attacked Britain many centuries earlier.

Some of the events that Geoffrey claims to have occurred at this point in British history can be observed in British lore in general, indicating that they were indeed derived from oral tradition. Modern audiences are likely to instantly recognize the story of King Lear, which William Shakespeare would turn into a play hundreds of years after The History of the Kings of Britain was written. A lesser known fact is that other Elizabethan playwrights penned plays concerning Lear and different kings that Geoffrey wrote about. There is another tale, that of the brothers Belinus and Brennus, which may initially seem to be fantasy but possibly has roots in reality. Belinus and Brennus both desire the British kingship and fight multiple civil wars over it, which on one occasion leads to Brennus fleeing to Gaul. While in this foreign land, he befriends Segnius, the Duke of the Allobroges, and eventually becomes duke himself. After the brothers decide to put aside their differences and unite, they fight various leaders in what would one day be France and then go on to invade Italy. They even sack Rome herself.

The idea of the Britons sacking Rome at a time well before the Romans had ever reached Britain may seem preposterous. Geoffrey concludes his biographical information on Brennus by stating that “I have not attempted to describe his other activities there or his eventual death, for the histories of Rome explain these matters.” By “histories of Rome,” Geoffrey is likely referring to a 9 BC work of this name by the ancient Roman historian Livy, who writes of the Celts sacking Rome early in her history. Leading the Celts in this endeavor was a chieftain by the name of Brennus. Much later in Roman history, when Julius Caesar battled the Gauls, these enemies of his often received aid from the Britons, so there easily could have been Britons involved in the events described by Livy. Brennus could actually have been born in Britain, or his acclaim amongst the Celtic tribes may have caused the Britons to claim that he was one of them. As the title of The History of the Kings of Britain suggests, there are descriptions of the lives of many other British kings, including in the pre-Roman era.

A rising action in the narrative of the book is when the Romans arrive on British soil. Geoffrey asserts that Julius Caesar led the earliest Roman expeditions to Britain, as the Roman general himself attested to in his 52 BC memoir Commentaries on the Gallic War. Caesar states in his memoir that he wished to explore Britain due to her people providing support to the tribes in Gaul that he was fighting. However, Geoffrey claims that he launched an invasion after the Britons rejected his demand that they immediately submit to Roman rule. As this is the time that the Romans started to write down information about events occurring in Britain, it is often said to be when the “recorded history” of the island begins. Other medieval accounts of British history concur with this notion, for they mostly ignore the earlier centuries described in The History of the Kings of Britain. Gildas says nothing of Britain before the Romans. In Ecclesiastical History of the English People by Bede, Chapter 1 is a summary of Britain as an island, while Chapter 2 begins with the words “Britain remained unknown and unvisited by the Romans until the time of Gaius Julius Caesar.” Nennius and Henry of Huntington skip to the arrival of Julius Caesar after their descriptions of Britain being settled.

The account given by Geoffrey of Julius Caesar and his activities in Britain does not contradict Bede, Nennius, or Henry of Huntington in any major way, although he provides far greater detail. Each of the chronicles describe Caesar failing in his first invasion and defeating the united forces of Cassivelaunus in the second. Bede, unlike the others, asserts that the Romans lost control of Britain right after Caesar departed from the island and did not regain it until the reign of Emperor Claudius. Geoffrey tells his reader that Britain was reduced to a tributary state after the campaign led by Caesar, with Claudius invading when the Britons stopped paying the tribute owed to Rome. Between the initial subjugation and the resumption of war, Geoffrey says that the Britons would be ruled successively by Tenvantius, Cymbeline, and Guiderius. Tenvantius and Cymbeline are known to modern historians as descendants of Cassivelaunus who were later leaders of his tribe, and Cymbeline was another figure that Shakespeare penned a play about. Details about the war with Claudius, however, are very fanciful and therefore dubious.

Sometimes The History of the Kings of Britain downplays the importance of Roman rule at this time in favor of discussion of local affairs of the Britons. Both Bede and Geoffrey mention a certain King Lucius. They agree that, in 156 AD, Lucius was the first British king to convert to Christianity and that many other Britons were soon to follow in his footsteps. Lucius is mentioned in other medieval sources, and scholars today continue to debate whether or not he really existed. Geoffrey later describes the persecution of British Christians by the Emperor Diocletian, a despot whose oppressive actions are also condemned by Gildas and Bede. During their accounts of the Diocletian persecutions, Bede and Geoffrey both tell of the martyrdom of St. Alban. All of the chroniclers write that the Roman Empire struggled more and more with usurpers at this point in time, some of whom came from Britain, and that this weakened imperial resources. In a year that Bede assigns as 409 AD, the Romans were forced to withdraw from the island forever.

Geoffrey writes of a leader coming to power in Britain after the Roman departure named Vortigern. Gildas, Bede, Nennius, The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles, and Henry of Huntington all also include him. They discuss Vortigern warring with the Picts, whom Geoffrey says that he antagonized after he had some of them executed for assassinating his predecessor. It was what would happen next according to the medieval chroniclers, a tale which many modern historians dispute the accuracy of, that changed Britain forever. In the year said by The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles to have been 449 AD, Vortigern hired the Saxon brothers Hengist and Horsa to help him in the war that he was losing against the Picts. Hengist and Horsa, according to Geoffrey and the other chroniclers, were very successful in fighting the Picts. The History of the Kings of Britain says that this allowed the brothers to convince Vortigern to allow more and more Saxon warriors to come to Britain until they were able to turn on the army of the king.

The History of the Kings of Britain concludes with the victory of the Saxons but a glimmer of future hope for the Britons. Vortigern encountered a young Merlin, who told him of his doom and symbolized the events of the future by showing him a battle between a red and white dragon. This same prophetic vision is also found in the work of Nennius. After the death of Vortigern, the Britons enjoyed some military success against the Saxons and reached their peak of glory, says Geoffrey, under King Arthur. He died of wounds sustained in battle in 542 AD, yet the Britons continued to resist under eleven more kings until the death of King Cadwallader in 689 AD. Arthur is also described by Nennius and Henry of Huntington as having led battles against the Saxons. Historians today tend to dismiss the possibility of the existence of Arthur, just as they dismiss the value of Geoffrey, yet sometimes lore and oral tradition go a long way in outlining the events of history.

#analysis#art#Arthurian legend#article#britain#British history#Britons#celtic#dragon#essay#geoffrey of monmouth#history#king arthur#Kings#legends#literature#medieval#medieval literature#Middle Ages#welsh

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

Boudicca

Krita, March 2023

Inspired by a short video I watched about the "Boudican Destruction Horizon," a layer of archeological artifacts and debris that resulted from the Boudican Revolt.

Time Lapse Video

#boudica#boudicca#queen boudica#ancient history#women in history#roman empire#britons#celtic#celts#women's history month#destruction#devestation#boudican destruction horizon#krita illustration

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Full-length Portrait of King Cassivellaunus (Cymbeline), King of the Catuvellauni, Ancient Briton & Chieftain commanding against Roman Emperor Julius Cesar.

Learn more / Daha fazlası

Cassivellaunus https://www.archaeologs.com/w/cassivellaunus/

#archaeologs#archaeological#dictionary#history#cassivellaunus#cymbeline#catuvellauni#ancient briton#britons#chieftain#roman empire#julius cesar#commander#illustration#art#united kingdom#arkeoloji#tarih

40 notes

·

View notes

Link

Author

Hume, David, 1711-1776

Title The History of England in Three Volumes, Vol. I., Part A.

From the Britons of Early Times to King John

Language English

LoC Class

DA: History: General and Eastern Hemisphere: Great Britain, Ireland, Central Europe

Subject

Great Britain -- History

CategoryText

EBook-No.19211

Release Date Sep 8, 2006

Copyright Status Public domain in the USA.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

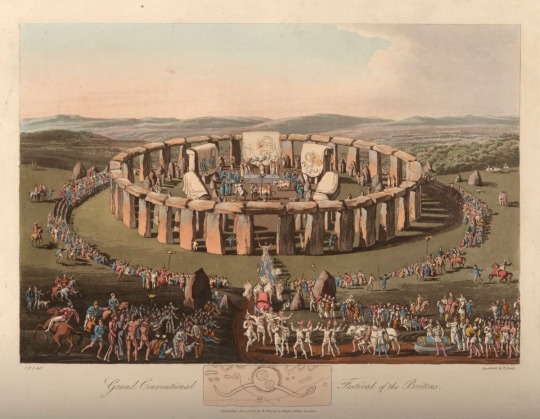

Grand Conventional Festival of the Britons

The costume of the original inhabitants of the British islands, by Samuel Rush Meyrick and Charles Hamilton Smith, Esq.

#ancient britain#britons#festival#stonehenge#british isles#art#history#symbols#serpent#snake#dancing#worship#altar#procession#bull#ox#samuel rush meyrick#charles hamilton smith

27 notes

·

View notes

Photo

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

There has recently been the suggestion that an Iron Age king, just revealed in England, could have ruled from Danebury Fort, a strategic hillfort, which overlooks the Hampshire landscape. So what is this fort’s story?

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Britons are quite separated from all the world.

Virgil

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Three Britons killed in Gaza named, IDF says strike was “unintentional”

Three British aid workers killed in an Israeli airstrike in the Gaza Strip on Tuesday have been hailed as “heroes” amid growing international condemnation of the attack, The Scotsman reports.

World Central Kitchen (WCK) confirmed that Britons John Chapman, 57, James “Jim” Henderson, 33, and James Kirby, 47, who worked on the charity’s security team, were among the seven staff killed.

The team leader, Australian Lalzawmi “Zomi” Frankcom, 43, also died, as well as an American-Canadian with dual citizenship Jacob Flickinger, 33, a Polish national Damian Sobol, 35, and a Palestinian Saifeddin Issam Ayad Abutaha, 25.

According to The Times, Mr. Chapman was a former Royal Marine from Cornwall who was due to leave Gaza on Monday, while The Sun reported that he had previously served in the Special Boat Service, the Royal Navy’s special forces unit. According to The Daily Telegraph, Mr. Henderson was also a former Royal Marine and Mr. Kirby is also believed to be a military veteran.

Read more HERE

#world news#world politics#news#middle east#middle east conflict#middle east news#middle east war#middle east crisis#israel palestine conflict#israel hamas war#israel hamas conflict#israel defense forces#idf#gaza strip#gaza under attack#gaza news#gaza war#gaza#briton#britons

0 notes

Photo

For my book, in order to understand how the British viewed their own history in medieval times, I have been reading the Penguin Classics edition of “The History of the Kings of Britain.” This work was originally written in Latin by Geoffrey of Monmouth and published in 1136. Scholars always disputed its accuracy, and those in the present day treat it as a work of fiction. Some of the more dubious claims in the book include the Britons being descended from Trojan colonists and that they invaded the Italian peninsula prior to the later takeover of Britain by the Romans. Also sometimes present are elements of fantasy. The book is still important in several ways, however. Even if the history given is highly inaccurate, there previously existed few books attempting to chronicle British history. Some of the key events in the book were embellished but did genuinely occur, including the invasion of Britain by Julius Caesar, the conquest of Britain by Rome, the integration of the British into the Roman empire, the introduction of Christianity into Britain, the persecution of early British Christians, the “barbarian” invasions that forced Rome to abandon Britain, and the occupation of Britain by the Saxons after the Romans withdrew. Perhaps most consequential in terms of cultural impact, Geoffrey of Monmouth was the first author to write down stories about King Arthur.

#arthurian legend#book#britain#britons#caesar#chronicles#culture#fantasy#fiction#geoffrey of monmouth#history#italy#julius caesar#king arthur#kings#latin#legends#literature#medieval#middle ages

6 notes

·

View notes