#canaanite religion

Text

Asherah/Athirat/Elat = Mother goddess, queen of heaven, goddess of fertility, lady of wisdom, goddess of the seas, the creator of the gods together with the god El, queen of the gods, the one who walks on the sea, patron saint of sailors and fishermen

Athirat is a powerful Goddess, and the other Gods often ask Her to help them, or to try to influence her husband El for their good. As guardian of Wisdom, She is the one who chooses the successor of Aleyin (an aspect of Ba'al as the God of dying vegetation) and, after his death, She instructs Anat in the proper ritual necessary to ensure the fertility of the vines.

Like Ashtart, Athirat is associated with the lion. She is usually shown as a nude Goddess with curly hair covering her breasts with her hands. She is also associated with the snake, and an alternative name for Her is Chawat, which in Hebrew translates as "Hawah", or in English "Eve"; so She may well be the root of the biblical Eve. Like the Carthaginian goddess Tanit, whose name means "Serpent Lady", Athirat was represented as a palm tree or pillar with a snake coiled around her, and the name Athirat derives from a root meaning "straight".

Athirat is associated with the Tree of Life, and a famous ivory box lid of Mycenaean finish found at Ugarit, dated 1300 BC, shows it symbolically representing the Tree. She wears an elaborate skirt and jewelry, and although she is topless, her hair is delicately styled; She is smiling and in her hands holds sheaves of wheat, which she offers to a pair of goats.

#history#Asherah#asherah goddess#asherah#Goddess#canaanite religion#canaanite mythology#Phoenician mythology#mythology#biblical#biblical mythology#athirat#Mother#Biblical goddess#pagan#God's wife#El'wife#Wife of god

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hadad from Canaanite religion.

The Canaanite religion encompassed the array of ancient Semitic beliefs followed by the Canaanite people in the ancient Levant, spanning from the early Bronze Age to the first centuries CE.

Hadad's representation featured a bearded figure adorned with a bull-horned headdress, wielding a club and a thunderbolt. As the consort of Atargatis and the father of Gibil or Girra, he held sway over land and human fertility. Linked to Zeus in Greek mythology, Jupiter in Roman lore, and Teshub in Hurrian beliefs, Hadad stood as a prominent and influential deity in the ancient Near East.

Follow @mecthology for more mythology and legends.

Pic generated using AI.

Source: Wikipedia and various.

#mecthology#mythology#myth#legends#hadad#Canaanite religion#canaanite#ancient#mitoloji#follow#zeus#gods#pagan

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Zeus himself, the central character in Hesiod’s Theogony, bears some of the most easily recognizable Northwest Semitic features, in addition to those of the Indo-European Sky God inherited by the Greeks. It is not necessary, therefore, to discuss them at length. It suffices to recall that the Canaanite Storm God Baal and the homologous Greek god share a similar position in the succession of kings in Heaven, as well as the position of the youngest son. They both reign from a palace on a northern mountain (Olympos, Zapanu/Zaphon), and they wield thunder as their distinctive weapon. As with his Near Eastern counterparts, thunder, lightning, and the thunderbolt were the “missiles/shafts of great Zeus.” The position of his sister and principal consort Hera is like that of Anat, Baal’s sister and partner (though not consort). For some, this coupling “violates the incest taboo” in Greek myth but allows Hera to remain an “equal” partner according to her right of birth, as the daughter of Kronos. In Il. 4.59 she is the oldest daughter, in Il. 16.432,18.352 she is called “sister and wife” and in Hesiod Th. 454 she is the youngest daughter of Kronos, exactly as Zeus is the last son.

The list of similarities between Zeus and the different manifestations of the Canaanite god (either Baal or El or Yahweh in the later Hebrew theology) is long and has been the subject of much discussion by classicists, Semitists, and biblical scholars. Perhaps most interesting are the parallels noticeable at the level of their epithets, such as Zeus the “cloud-gatherer” (nephelegereta)or “lightener” (asteropetes), and the frequent characterization of Baal in Ugaritic poetry as the “cloud-rider” (rkb ʿrpt). Other epithets of the Northwest Semitic Storm God Adad (Haddad) are preserved in Akkadian hymns, such as “lord of lightning” or “establisher of clouds.” …

Zeus’ “high-in-the-Sky” position and Sky-nature are reflected in other epithets such as hypatos and hypsistos. At the same time, similar divine epithets meaning “the high one” (eli, elyon, and ram) are very common in Northwest Semitic religious texts, accompanying several principal divinities. For instance, this epithet is used in the Ugaritic epic for Baal, and different forms of the adjective are attested in Aramaic, as well as in the Hebrew Bible accompanying El, Yahweh, and Elohim. … The association of the Storm God in Syro-Palestine with the bull as a symbol of fertility is also present in the various mythological narratives involving Zeus, most clearly in the famous motif of Zeus’ kidnapping the Phoenician princess Europa and carrying her on his back after taking the shape of a bull.

The final fight of Zeus with Typhon (Th. 820-880) has also been compared to the fight between Baal and Yam (the Sea) in the Ugaritic Baal Cycle and to that between Demarous and Pontos (the Sea) in Philon’s Phoenician History (P.E. 1.10.28). As mentioned earlier, the Storm God’s struggle with a monster also (albeit more distantly) resembles the clash between the Hurrian Weather God Teshub and the monsters Ullikummi, Illuyanka, and Hedammu. The figure of Typhon in Hesiod can in fact be seen as a Greek version of a “cosmic rebel” repeatedly reimagined with different characteristics in the specific versions, who endangers the Weather God’s power and generally has both marine and chthonic features. The Levantine and Greek adversaries probably have more than a merely thematic resonance, as the very name of Typhon might have a Semitic origin. It has hypothetically but quite convincingly been associated with the Semitic name Zaphon. Mount Zaphon (Ugaritic Zapunu or Zapanu) is a central point of reference in the geography and the religion of Ugarit. Known by Greeks and Romans as Kasion oros/ mons Casius (today Jebel al-Aqra), this peak on the north coast of Syria (south of the Orontes River) was also mentioned in Hurrian-Hittite myths. The mountain occupies a central spot in both the fight between Ullikummi and Teshub (as Mount Hazzi) and in the Ugaritic Baal Cycle. In the Ugaritic epic, the fight against Yam (the Sea) is not described as taking place on the mountain, but the celebration of Baal’s victory is, as it is the god’s abode overlooking the Mediterranean: “With sweet voice the hero sings / over Baalu on the summit / of Sapan (= Zaphon).” Much later, Apollodoros locates the cosmic fight with Typhon on Mons Casius precisely, which indicates that the link between Typhon and Zaphon had persisted, even though the name known to Hellenistic authors was the Greek, not the Semitic one."

- When the Gods Were Born: Greek Cosmogonies and the Near East by Carolina López-Ruiz

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Enoch, an apocryphal text thought to be written sometime between the third century B.C. and the second century A.D., is named for the biblical Noah’s great-grandfather. One reason Langlois didn’t know much about the book was that it didn’t make it into the Hebrew Bible or the New Testament. Another is that the only complete copy to survive from antiquity was written in an ancient Ethiopic language called Ge’ez.

But beginning in the 1950s, more than 100 fragments from 11 different parchment scrolls of the Book of Enoch, written largely in Aramaic, were found among the Dead Sea Scrolls. A few fragments were relatively large—15 to 20 lines of text—but most were much smaller, ranging in size from a piece of toast to a postage stamp. Someone had to transcribe, translate and annotate all this “Enochic” material—and Langlois’ teacher volunteered him. That’s how he became one of just two students in Paris learning Ge’ez.

Langlois quickly grasped the numerous parallels between Enoch and other books of the New Testament; for instance, Enoch mentions a messiah called the “son of man” who will preside over the Final Judgement. Indeed, some scholars believe Enoch was a major influence on early Christianity, and Langlois had every intention to conduct that type of historical research.

He started by transcribing the text from two small Enoch fragments, but age had made parts of it hard to read; some sections were missing entirely. In the past, scholars had tried to reconstruct missing words and identify where in the larger text these pieces belonged. But after working out his own readings, Langlois noticed the fragments seemed to come from parts of the book that were different from those specified by earlier scholars. He also wondered if their proposed readings could even fit on the fragments they purportedly came from. But how could he tell for sure?

To faithfully reconstruct the text of Enoch, he needed digital images of the scrolls—images that were crisper and more detailed than the printed copies inside the books he was relying on. That was how, in 2004, he found himself traipsing around Paris, searching for a specialized microfiche scanner to upload images to his laptop. Having done that (and lacking cash to buy Photoshop), he downloaded an open-source knockoff.

First, he individually outlined, isolated and reproduced each letter on Fragment 1 and Fragment 2, so he could move them around his screen like alphabet refrigerator magnets, to test different configurations and to create an “alphabet library” for systematic analysis of the script. Next, he began to study the handwriting. Which stroke of a given letter was inscribed first? Did the scribe lift his pen, or did he write multiple parts of a letter in a continuous gesture? Was the stroke thick or thin?

Then Langlois started filling in the blanks. Using the letters he’d collected, he tested the reconstructions proposed by scholars over the preceding decades. Yet large holes remained in the text, or words were too big to fit in the available space. The “text” of the Book of Enoch as it was widely known, in other words, was in many cases mistaken.

Take the story of a group of fallen angels who descend to earth to seduce beautiful women. Using his new technique, Langlois discovered that earlier scholars had gotten the names of some of the angels wrong, and so had not realized the names were derived from Canaanite gods worshipped in the second millennium B.C.—a clear example of the way scriptural authors integrated elements of the cultures that surrounded them into their theologies. “I didn’t consider myself a scholar,” Langlois told me. “I was just a student wondering how we could benefit from these technologies.” Eventually, Langlois wrote a 600-page book that applied his technique to the oldest known scroll of Enoch, making more than 100 “improvements,” as he calls them, to prior readings.

His next book, even more ambitious, detailed his analysis of Dead Sea Scrolls fragments containing snippets of text from the biblical Book of Joshua. From these fragments he concluded that there must be a lost version of Joshua, previously unknown to scholars and extant only in a small number of surviving fragments. Since there are thousands of authentic Dead Sea Scrolls, it appears that much still remains to be learned about the origins of early biblical texts. “Even the void is full of information,” Langlois told me.

— How an Unorthodox Scholar Uses Technology to Expose Biblical Forgeries

#chanan tigay#michael langlois#how an unorthodox scholar uses technology to expose biblical forgeries#history#religion#christianity#judaism#canaanite religion#languages#linguistics#translation#palaeography#forgeries#bible#torah#dead sea scrolls#technology#digital technology#canaan#book of enoch#aramaic#ge'ez

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Yahweh and Asherah in the Hebrew Bible

Yahweh and Asherah in the Hebrew Bible

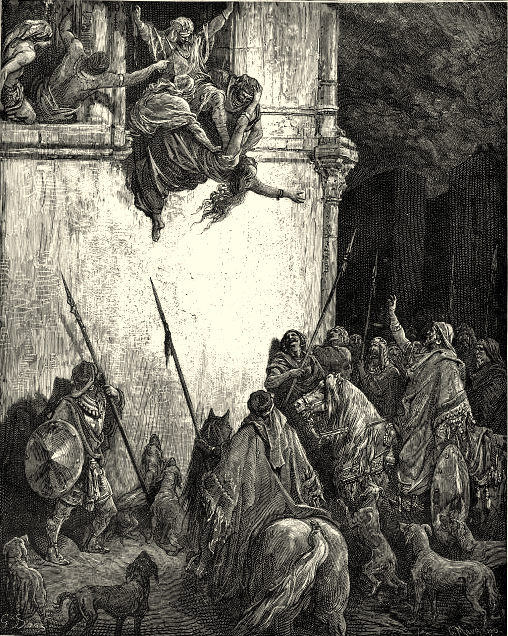

The Death of Jezebel, by Gustave Doré, 1866. From wikipedia.org

The Hebrew Bible uniformly recognizes the unique deity of the Lord, the God of Israel who identifies himself to Moses as “I AM” transliterated as Yahweh. Only he is the God of the heavens and the earth, the creator of all things, the sole Lord of the heavenly hosts who sits on his throne ruling over the divine council. In contrast…

View On WordPress

#academic#ANE#Asherim#Asheroth#Athirat#Baal#Canaanite religion#Comparative religion#fertility#goddess#paganism#Patrick Quinn#scholarly#Take Note Of This#TNOT#Ugarit#YHWH

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Title: YHWH had a Wife?

Channel: ReligionForBreakfast (Dr. Andrew Henry)

Length: 4:54

Explores a temple with evidence for worship of two deities; YHVH and his consort or wife. Inscriptions elsewhere describe YHVH and "his Asherah." Asherah is a Canaanite goddess, consort to Canaanite god El. References to "his Asherah" may be referring to a now-unknown object. Word "Asherah" appears 40 times in Bible and is usually referring to cult object and not a deity. Touches on diversity in ancient Israelite religion.

#Asherah#Asherah Poles#Ancient Israelite religion#Canaanite religion#Canaanite origin of Judaism#Youtube

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Syncretism in the Old Testament

Syncretism in the Old Testament

BaalThe Canaanite God

Syncretism is the merger of different, and at times, contradictory religious practices, faith, and beliefs in order to reconcile different religious traditions found within a community and in order to find unity between competitive views.

Syncretism in the Old Testament involves Israel’s absorption of Canaanite religious practices into the religion of Yahweh. Syncretism…

View On WordPress

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

According to my scant, second hand knowledge of the Jewish religion (idek the proper name, don't @ me), Catholicism, and Christianity, back when Jews were nomads, way before they settled down in one place, their god Yahweh was, in two words, a vicious dickhead of a storm god, and only after they settled down in Canaan did they try to calm him down by doing the theological equivalent of murdering the real wise and kind skydaddy god, El, blessed be his name, and then have Yahweh wear his flayed skin like some sort of grotesque mask and eat the rest, and that frankly goes pretty hard. Anyways I'm SOOO co-opting that into my writing, imagine worshipping the god that killed the supreme skydaddy and ate his corpse to gain his might. That's baller.

Edit: After further study, I have concluded that Yahweh was once an aspect of Qos, a mountain, weather and war god of the Edomite people. The ancient Israelites of Canaan then did a systematic eradication of every other god in the greater Canaan religion, including such gods as El and Asherah, Yam and Lotan, Arsu and Azizos, Aglibol, Malakbel, Yahribol, Bel, and Ba'al Hadad. In their shame after the crushing of the ancient Jewish kingdom under Babylon, the Jews, jealous in the banning of sacrifices to Yahweh, later wrote into their own Bible the banning of sacrifices to all gods. But Yahweh took sacrifices, and Yahweh took sacrifices in human infants, for Yahweh was a fellow Canaanite god just like the rest of them.

Edit 2: THIS POST IS ABOUT THE PRE-JUDAISM YAHWIST CULT OF THE ANCIENT CITY STATE OF ISRAEL AND HOW IT BECAME THE MODERN CULTS. Having to add this because some fucking [REDACTED] in the comments think that literal historical facts (with added hyperbole) is antisemitic somehow. They know who they are.

#worldbuilding#gods#worldbuilding religion#truth is stranger than fiction#but fr tho the ancient canaanites were nomadic raiders#and bandits too#and their god were similarly violent#only after they settled down did they try to smooth things out#the draft was made before oct 7#in the spirit of keeping it straight i won't comment on the newer news here#jewblr#jumblr

62 notes

·

View notes

Note

i have a religon question. we all have indigenous gods, right? especially in 'the east.' do abrahamic religions see these gods as fake, or just another part of god, or djinn and demons? I know there are people who are jewish or muslim or christian living in places with a large population that follows the kind of religion that respects ancestors and hometown gods; do those people also get to pay respects to those deities? do they get a pass for that because they, too, are technically protected by those indigenous gods even though they technically converted, but they're still of that land?

(could that be applied to earth kingdom spirits, bc there's so many of them?)

Hi! You are going to get a MONSTER response here, and it might not even fully answer your question, so... apologies in advance.

I want to start with your premise about indigenous gods. I think there are two elements that strike me as needing some kind of definition or clarification.

The first is: what does "indigenous gods" mean?

Please keep in mind that I am going to discuss indigenous RELIGION here, not "indigenous" as a political term.

I think there is a faulty assumption often applied to conversations around indigenous vs global religions that assumes that "indigenous religion" is polytheistic and "global religion" is monotheistic. One issue with that, in my opinion, is that "polytheistic" and "monotheistic" just aren't as meaningful as Western academia has historically stated. They are, in my opinion (though not only my opinion!), terms laden with Protestant ideology.

Protestantism and "Polytheism vs Monotheism":

Protestant religious scholarship tends to want to divide religion into the more primal, physical religious expression vs the more otherworldly, spiritual expression. Polytheism is, in Protestant academic mindset - excuse my language here, I'm making a point - a kind of barbaric, pre-enlightened, base form of religious expression. When religion gets more refined and intelligent and articulate, it sheds those earthly elements and ends up being monotheistic. This is Protestant in origin, specifically, because it is not only about how Protestant academics viewed religions like Hinduism or European indigenous religion, it's also about how they felt about Catholics and Jews. Catholics and Jews, from that mindset, might be "monotheistic", but they're holding onto the base, unrefined physicality of the old world. Catholics and Jews like physical rituals, physical prayer, rules around eating, etc. So yes, sure, they're monotheistic, but they haven't quite understood monotheism yet.

This is obviously not a nice thing to think about other peoples, but that's not what is interesting for our purposes. What's interesting is that Protestant academia has left much of the West with the above as their understanding of how religion functions. Even many atheists, by the way, will describe atheism as just the next step on that wrung; religion starts with polytheism, which is steeped in physical ritual and is obsessed with the earth, etc, then people became monotheistic and slowly let go of those earthly things, and then people got truly enlightened and realised there's no God at all. You can hear this in how some atheists will talk about believing in "one fewer god" than monotheists - that sense of the arc of progress and development.

Now, I hope you've already realised that I don't believe that's true. But let's break it down a little:

What is monotheism, and what is polytheism?

Judaism often has ascribed to it being the first monotheists. In some ways, that's true; in some ways, it isn't. There were One-God-isms that occurred elsewhere, too. Famously, in Egypt, the pharaoh Akhenaten led a religious reformation which narrowed worship down to Aten, the sun god. Nobody can agree on exactly what this was, but it was at least a focused religious expression. Likewise, Zoroastrianism was talking about a dual nature of reality in a way that could be read as monotheistic before the Jews were.

And when the Jews began to worship God as One, it wasn't exactly a clean break. It's actually fairly clear that the worship of the one we now just call God was really a slow development of theological focus, which we might now call henotheism: belief that multiple gods exist, but only worshipping one. Then that God slowly came to represent a kind of universality, especially with the experience of worshipping a land-based deity while in exile (first exile, starting c.586BCE).

So the Jewish belief in One God is a bit like Atenism: a focusing in on a particular god. Except this time, instead of one big religious revolution, it was a very slow religious development.

And if we want to divide not only into "monotheist" and "polytheist", but also into "indigenous" and "global", we're in very murky waters.

Indigenous Religion and Global Religion

Noting again that this can get politically tense because classifications of indigeneity are politically fraught. I'm interested in what makes a religion or culture indigenous, not in what that means for us politically.

Indigenous religion is difficult to define in a sentence, and so I will not try to do that. Here are multiple things that come together in indigenous religion in general instead: Indigenous religiosity is not distinguishable from culture itself. It's born of a land and developed over time. It might have its own myths about its origin (it likely will!), but those are often contradictory in some ways, because they are descriptions of important cultural narratives rather than histories. It tends to be uncentralised and is often slightly different depending on where you are in the land. It tends toward agricultural spirituality and concepts of holy soil. It is tied to an ethnic group and is generally uninterested in ideas of conversion (either into the group or out of the group); it may even be hostile to outsiders joining.

Global religions, on the other hand, tend to be much more planned-out. A global religion is born from a person or a group of people. One can see its birthplace and origin. It is devised in order to spread, and therefore is not attached to one land or to one ethnic group (so that it can move both geographically and through conversion of others into the group). It tends toward centralisation in an organisational capacity.

So. Is Atenism indigenous? ... Well, kind of yes, kind of no. Worship of Aten is born from the land of Egypt, but having a specific historical revolution makes it seem a little outside the "indigenous" definition. But it's definitely not global either. So we've immediately located something that doesn't seem to work well in a binary sense.

Is Judaism indigenous? ... Pretty clearly "yes". It's a land-based agricultural religion born of a particular land, with strong ethnic ties, that developed over time (rather than being born of a historical moment), that isn't interested in spreading or converting and wants to be in its holy land, is uncentralised and disorganised in nature, etc. But people don't tend to talk about Judaism that way, because Judaism has survived a 2,000-year exile, which is pretty unheard of. Once you've been kicked out of the land that long, it feels like it should be a global religion. But it doesn't fit any of the critera for that.

I think that Judaism being an indigenous religion that learned to survive outside the land is part of the reason that people have such a hard time understanding what Judaism is. It seems, from the outside, like it should function more similarly to Christianity and Islam. But in most ways, it just doesn't.

(Also, it would be remiss of me not to note: there's also a lot of political discomfort around calling Judaism an indigenous religion, because most indigenous cultures haven't reclaimed sacred land after being colonised, and the Modern State of Israel a) exists and b) is acting as an oppressive force. Some people will define groups as indigenous specifically only if they are currently being oppressed within their land of origin. As an academic, I think that's a poor definition, and it's certainly not helpful for defining indigenous religion. But I understand the political discomfort.)

Hinduism is also a really interesting example of this. Hinduism is similar to Judaism in some ways, as it's an indigenous, land-based religion that learned to exist outside of the sacred land. It often gets miscategorised on the basis that it's spread geographically (and unlike Judaism, that spread was not simply by outside force). In some ways, Hinduism acts like a global religion, but it doesn't really fit the bill.

Therefore:

a) "Indigenous religion" isn't always polytheistic (if that's even a meaningful term)

b) Some religions fit into neither category (such as Atenism)

c) Some religions fit into one category but aren't categorised that way by outsiders for various reasons (such as Judaism)

And to add another point: Buddhism is a great example of a global religion. Born of a historical person and moment, ease to spread and convert, not tied intrinsically to land. But try defining Buddhism according to the Protestant theistic categories. I dare you. So:

d) Global religions aren't always monotheistic

"Monotheism" and Global Religions

With that in mind, let's talk about Christianity and Islam. They are the major religions of the world. Christians make up around 30% of the world, and Muslims make up around 25% of the world. And frankly, the 15% of the world who call themselves secular/atheist/etc... I think meaningfully belong to Christianity and Islam, too. I know people often don't like that, but the idea that you have to believe something to belong to a religion is a specific religious idea that I don't ascribe to.

A lot of the time, the way that religion is conceptualised is therefore through a Christian or Muslim lens. (See: my point just above about "faith" in religion.) This has completely muddied the waters of how we discuss and conceptualise our own religions and cultures, let alone other peoples.

Your original question was about Abrahamic religion, so I'm going to try to address that here, but please keep in mind: in a question about indigenous gods, putting Judaism in the same realm as Christianity and Islam is dodgy territory and we need to walk it carefully.

"we all have indigenous gods, right? especially in 'the east.' do abrahamic religions see these gods as fake, or just another part of god, or djinn and demons?"

Judaism: Judaism is an evolution that occurred within Canaanite religion. It started with narrow worship of a local god and slowly universalised, especially when the Israelites were trying to survive outside the place of the local god. The seeds of that universalisation already existed before the first exile, which is likely why it worked. It had a confused relationship with the other local gods; outright worship of those "other gods" was frowned upon but still existed among the peoples, and that worship kind of melded into the narrow worship of the One God. You can see this in how many of the names of God that appear in the Bible are actually the names of the local Canaanite gods.

After the first exile, Judaism became more solid in its sense of theological universalism. Jonah is a great example of this as a book; Jonah was written post-exile (though set pre-exile), and it starts with an Israelite trying to run away from God. It seems absurd to us now, because we know that the Jewish God is universal, but the character of Jonah seems to honestly think he can escape God by leaving the land. The rest of the book is about Jonah's struggle to understand how his god also has a relationship with the people of Nineveh. It's a great example of the struggle of universalising theology.

(By-the-by, I think "universal theology" is a much more useful term than "monotheism", but that's a rant for another day.)

What began as a narrowing ("henotheism"), which was both pushing out and incorporating other local traditions, then had to contend with the worship of the oppressive forces of outside religion. Assyrians, Babylonians, Greeks, and Romans are all peoples who attacked, colonised, exiled, etc - and they all came in with their gods. The Greeks even instituted worship of their gods in our Temple. Our worship was made illegal by the colonisers. Relationship with "idol worship" was about relationship with those outside forces.

In short, the literature itself is very confused about what those gods actually are. Jews were certainly not supposed to worship them, and should go to great lengths to avoid them. (If we didn't, we probably wouldn't still exist, so: good shout.) Sometimes they get talked about like neighbouring gods, which is a holdover from the narrowing-days (where those other gods existed, but we worshipped our own native land-based god). Sometimes they get talked about as false idols created by people who are either misunderstanding reality or deliberately trying to have control over the divine (which developed more as the God-worship was universalised). The more universalised our theology became, the more we started shrugging of ideas of neighbouring gods that actually existed, and the more it became about the latter.

(Note: When Jews met religions that call a universal God something else, they would then tend to conclude that it's not idol worship. This developed when Judaism met Islam in more peaceful moments. The idea that non-Jewish religions could be something other than idolatry then came to include Christianity - but only kind of, because of the worshipping-a-person issue - and then religions like Sikhism much more easily. It's even arguable that religions like Hinduism aren't exactly "idol worship" for non-Jews, because many Hindus will describe what they believe in in universal terms - Brahman is first cause and all emanates from him - even if their worship includes references to "multiple gods". This does not mean Jews are allowed to worship that way.)

Christianity: Christianity was born in a specific historical moment, utilising previous Jewish and Hellenistic thought. It almost immediately became a religion of conversion (I would put that distinction at the year 50, with the Council of Jerusalem). Since it was born from a universalised theology, it already had the bones of the idea of a universal God; now, it also had the will to spread, both geographically (shrugging off major religious ties to the Holy Land) and religiously (not only could people convert, but people should convert). While Judaism was all about avoiding worship of other gods, Christianity became about converting those peoples.

Islam: Islam was born in a specific historical moment, utilising previous Christian, Jewish, Zoroastrian, and pre-Islamic Arabian thought. It immediately became a religion of conversion. In this sense, it's a lot more like Christianity than anything else, except Christianity developed most significantly after the death of Jesus. Islam got a lot more time in development with Mohammed. In some ways, I think this really benefitted Islam (though that's not to say some things didn't get... complicated, upon his death). It inherited from Christianity the sense that worship of other gods was something to be responded to with conversion.

"I know there are people who are jewish or muslim or christian living in places with a large population that follows the kind of religion that respects ancestors and hometown gods; do those people also get to pay respects to those deities? do they get a pass for that because they, too, are technically protected by those indigenous gods even though they technically converted, but they're still of that land?"

Short answer: no. Jews, Christians, and Muslims do not believe that those deities exist as separate to the universal God.

Longer answer for Judaism, because... well, I know more about lived Judaism than lived Christianity or Islam*:

(I recently said to someone IRL: I do have a degree in Catholic Theology, but I don't know anything about what Catholics ACTUALLY believe.)

It would be absolutely disallowed in Judaism to participate in worship of "other gods". Modern Jews will not believe those gods exist (at least, I've never come across that either IRL or in studies). However, Judaism does still hold that worship is a powerful thing and that Jews are not allowed to participate in worship of "other gods". Many Jews will say it's not worship of "other gods", it's just worship of the one universal God that is understood differently by different cultures. This does not change the fact that Jews are not allowed to participate in it.

(In fact, it's one of the three things a Jew should rather die than participate in. It's a little murkier than this, but basically: even under duress, even on pain of death, a Jew should never murder, commit sexual violence, or worship an idol.)

"(could that be applied to earth kingdom spirits, bc there's so many of them?)"

Yes, I think the Earth Kingdom in ATLA is supposed to function in an indigenous manner, specifically in indigenous religion as it acts over a wide spread of land. That is to say, like Hinduism, or like when you compare different arctic indigenous cultures or African indigenous cultures. There isn't a centralised force (like with the FN); it's local gods - or here, spirits - that have their own myths, etc.

Please note, I have avoided talking about nomadic cultures here on purpose, because this would be twice as long! This is not exhaustive at all. I hope it makes at least some sense.

#jew on main#judaism#christianity#islam#buddhism#hinduism#it's a world religion extravaganza#canaanites#not the kindest post to protestants#atenism

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

Baal/Bael/Ba'al = It is a title meaning "lord" or "master", There were many local Baals. The greatest, known as the “Great Baal”, is Son of the Father of the Gods, El, and Brother of the God of the seas and rivers, Yam-Nahar. Baal, known as “Knight of the Clouds”, is a God of fertility who represents the beneficial aspects of water such as rain. His lightning and thunder represent his Power, and the fertile land his beneficence.

#history#Baal#demon#God#God of agriculture#God of fertility#god of storms#god of fertility#weather god#God of weather#canaanite mythology#Phoenician#Biblical god#Pagan#fallen angel#Demon king#Biblical#old testament#Bible#Mythology#Phoenician mythology#canaanite religion#Canaanite

35 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mythologic Geekery: Ba'al

Given that I now have the theory that he might play into Nocturne - and the fact I wanted to speak about Abrahamitic and Semitic mythology this and next week either way... LET ME TALK BA'AL!

So, first things first: Ba'al originally was a title within several of the semitic languages, being best translated with "Lord". So several male gods used the honorific over the time. But within both Babylon and also the Canaanite culture the name became mostly associated with the god Hadad. (While the Phoenicians associated the name with El(ohim) - but I am gonna talk about Elohim next week and he is a bit different, because he never became a demon.)

Hadad was a good mainly of weather (especially storms) and of fertility, being associated with the harvest and agriculture in general. Statues of Hadad were also used in fertility rituals.

From Ba'al Hadad came Ba'al as a god on his own. And while he was usually not the head god of a pantheon, he very much fulfilled the same role as Zeus in the pantheon. Being association with weather and these things. Interesting enough he had also a reverse version of the same kinda myth like Persephone associated with him: According to this myth the hot and dry summer months were the time of the year he was forced to live in the underworld.

What happened, though, with the Hebrew culture was that YHW subsumed the same role within the pantheon that Ba'al originally fulfilled. So he basically took that role and on the longterm subplanted Ba'al. And when the Abrahamitic culture turned towards Monotheism around YHW, Ba'al first became one of the false idols. Those idols that the folks prayed to in the desert while Moses was on the mountain. (Also Ba'al was among the idols people in Mekka prayed too that Mohammed then worked against.)

So, when Judaism took of they used Ba'al to build out their demonology. Now, again, Ba'al is technically a title, but a lot of people do agree that the fact that the demon got called Ba'al Zebub (Lord of Flies) was for the reason that Ba'al was the god they were trying to subplant.

Now technically Ba'al Zebub also references another god (Ekron). Now, the role of Ba'al Zebub (or how you might more easily recognize the name: Beelzebub). Within early Judaist sources Ba'al Zebub is mostly associated with death and sickness. Hence also the name: Lord of Flies.

As mythology shifts over time, by the time of the Testament of Solomon Ba'al Zebub was called "the Prince of Demons", who also was said to once have been an angel who rebelled against God for which he was cast into hell. And yes, if you think about Luzifer here: This was probably the source for that. I will talk more about Luzifer next week.

And then came Christianity. While within the gospels Ba'al Zebub was still in the same role of "prince of demon", later Christian theology started to decide that he and Satan were the same character. Something that happened around the same time that Satan became seen as more and more "evil" (something he is not within the original Hebrew mythology). And the Christian theology turned Ba'al Zebub into Beelzebub, as which we still have him around to this day.

#castlevania#castlevania nocturne#mythologic geekery#mythology#christian mythology#christianity#abrahamic religions#demonology#canaanite#phoenician

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Asherah, the original mother goddess of the early Semitic mythos. She was the wife of the supreme god El. Asherah birthed the Canaanite pantheon, from Baal and Astarte to Yam and Mot, all of them were born from her union with El. Asherah’s origins are unknown, however it’s believed that she was the feminine aspect of El. In one of the few surviving myths, Asherah is shown as Yam’s biggest supporter for the throne of the chief god. Her epithet of ‘Asherah of the sea’ illustrates just how important their relationship was. Despite her support, Yam ultimately loses to Baal for the throne. Asherah in modern abrahamic faiths was reduced to a false idol, with her ‘poles’ being targeted and destroyed.

Asherah is the earliest depiction of the Mother Goddess trope, with her role in Canaan being so influential it affected the religious landscape. The Mother Goddesses became a ubiquitous feature among polytheistic religions, to the point where the absence of one is something to note. Though her name was demonized in modern times, her essence still lives on in her descendants faiths. As Eve from the garden of Eden is proposed to be derived of Asherah. As El was the predecessor of the Abrahamic God, Asherah’s relationship to the omnipotent deity has become a focal point for her. Her legacy may even live on in the feminine aspect of modern god: Shekinah, and the gnostic Aeon: Sophia.

#art#character design#mythology#asherah#athirat#semitic#canaan#canaanite mythology#semitic mythology#judaism#christianity#mother goddess#goddess#tree god#false idols#fertility god#gnosticism#abrahamic religions#abrahamic mythology#deity

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

So who is Baal?

Baal or Baʻal, was a title and honorific meaning 'owner', 'lord' in the Northwest Semitic languages spoken in the Levant during antiquity.

Baal is a God of fertility, weather, rain, wind, lightning, seasons, war, sailors and so on.

Baal worship is also called Baalism.

Solid cast bronze of a votive figurine representing the god Baal discovered at Tel Megiddo, dating to the mid-2nd millennium BC.

His holy symbols are bull, ram and thunderbolt.

Baal was worshipped in ancient Syria, especially Halab, near, around and at Ugarit, Canaan, North Africa and Middle Kingdom of Egypt.

Baʿal is well-attested in surviving inscriptions and was popular in theophoric names throughout the Levant but he is usually mentioned along with other gods, "his own field of action being seldom defined". Nonetheless, Ugaritic records show him as a weather god, with particular power over lightning, wind, rain, and fertility. The dry summers of the area were explained as Baʿal's time in the underworld and his return in autumn was said to cause the storms which revived the land. Thus, the worship of Baʿal in Canaan—where he eventually supplanted El as the leader of the gods and patron of kingship—was connected to the regions' dependence on rainfall for its agriculture, unlike Egypt and Mesopotamia, which focused on irrigation from their major rivers. Anxiety about the availability of water for crops and trees increased the importance of his cult, which focused attention on his role as a rain god. He was also called upon during battle, showing that he was thought to intervene actively in the world of man, unlike the more aloof El. The Lebanese city of Baalbeck was named after Baal.

The Baʿal of Ugarit was the epithet of Hadad but as the time passed, the epithet became the god's name while Hadad became the epithet. Baʿal was usually said to be the son of Dagan, but appears as one of the sons of El in Ugaritic sources. Both Baʿal and El were associated with the bull in Ugaritic texts, as it symbolized both strength and fertility. He held special enmity against snakes, both on their own and as representatives of Yammu (lit. "Sea"), the Canaanite sea god and river god. He fought the Tannin (Tunnanu), the "Twisted Serpent" (Bṭn ʿqltn), "Lotan the Fugitive Serpent" (Ltn Bṭn Brḥ, the biblical Leviathan), and the "Mighty One with Seven Heads" (Šlyṭ D.šbʿt Rašm). Baʿal's conflict with Yammu is now generally regarded as the prototype of the vision recorded in the 7th chapter of the biblicalBook of Daniel. As vanquisher of the sea, Baʿal was regarded by the Canaanites and Phoenicians as the patron of sailors and sea-going merchants. As vanquisher of Mot, the Canaanite death god, he was known as Baʿal Rāpiʾuma (Bʿl Rpu) and regarded as the leader of the Rephaim (Rpum), the ancestral spirits, particularly those of ruling dynasties.

From Canaan, worship of Baʿal spread to Egypt by the Middle Kingdom and throughout the Mediterranean following the waves of Phoenician colonization in the early 1st millennium BCE. He was described with diverse epithets and, before Ugarit was rediscovered, it was supposed that these referred to distinct local gods. However, as explained by Day, the texts at Ugarit revealed that they were considered "local manifestations of this particular deity, analogous to the local manifestations of the Virgin Mary in the Roman Catholic Church". In those inscriptions, he is frequently described as "Victorious Baʿal" (Aliyn or ẢlỈyn Baʿal), "Mightiest one" (Aliy or ʿAly) or "Mightiest of the Heroes" (Aliy Qrdm), "The Powerful One" (Dmrn), and in his role as patron of the city "Baʿal of Ugarit" (Baʿal Ugarit). As Baʿal Zaphon (Baʿal Ṣapunu), he was particularly associated with his palace atop Jebel Aqra (the ancient Mount Ṣapānu and classical Mons Casius). He is also mentioned as "Winged Baʿal" (Bʿl Knp) and "Baʿal of the Arrows" (Bʿl Ḥẓ). Phoenician and Aramaic inscriptions describe "Baʿal of the Mace" (Bʿl Krntryš), "Baʿal of the Lebanon" (Bʿl Lbnn), "Baʿal of Sidon" (Bʿl Ṣdn), Bʿl Ṣmd, "Baʿal of the Heavens" (Baʿal Shamem or Shamayin), Baʿal ʾAddir (Bʿl ʾdr), Baʿal Hammon (Baʿal Ḥamon), Bʿl Mgnm.

The epithet Hammon is obscure. Most often, it is connected with the NW Semitic ḥammān ("brazier") and associated with a role as a sun god. Renan and Gibson linked it to Hammon (modern Umm el-‘Amed between Tyre in Lebanon and Acre in Israel) and Cross and Lipiński to Haman or Khamōn, the classical Mount Amanus and modern Nur Mountains, which separate northern Syria from southeastern Cilicia.

The major source of our direct knowledge of this Canaanite deity comes from the Ras Shamra tablets, discovered in northern Syria in 1958, which record fragments of a mythological story known to scholars as the Baal Cycle. Here, he earns his position as the champion and ruler of the gods. The fragmentary text seems to indicate a feud between him and his father El as background. El chooses the fearsome sea god Yam to reign as king of the gods. Yam rules harshly, and the other deities cry out to Ashera, called Lady of the Sea, to aid. Ashera offers herself as a sacrifice if Yam will ease his grip on her children. He agrees, but Baal opposes such a scheme and boldly declares he will defeat Yam even though El declares that he must subject himself to Yam.

With the aid of magical weapons given to him by the divine craftsman Kothar-wa-Khasis, Baal defeats Yam and is declared victorious. He then builds a house on Mount Saphon, today known as Jebel al-Aqra. (This mountain, 1780 meters high, stands only 15 km north of the site of Ugarit, clearly visible from the city itself.)

Lo, also it is the time of His rain.

Baal sets the season,

And gives forth His voice from the clouds.

He flashes lightning to the earth.

As a house of cedars let Him complete it,

Or a house of bricks let Him erect it!

Let it be told to Aliyan Baal:

'The mountains will bring Thee much silver.

The hills, the choicest of gold;

The mines will bring Thee precious stones,

And build a house of silver and gold.

A house of lapis gems!'

However, the god of the underworld, Mot, soon lures Baal to his death, spelling ruin for the land. His sister Anat retrieves his body and begs Mot to revive him. When her pleas are rebuffed, Anat assaults Mot, ripping him to pieces and scattering his remains like fertilizer over the fields.

El, in the meantime, has had a dream in which fertility returned to the land, suggesting that Baal was not indeed dead. Eventually he is restored. However, Mot too has revived and mounts a new attack against him.

They shake each other like Gemar-beasts,

Mavet [Mot] is strong, Baal is strong.

They gore each other like buffaloes,

Mavet is strong, Baal is strong.

They bite like serpents,

Mavet is strong, Baal is strong.

They kick like racing beasts,

Mavet is down. Baal is down.

After this titanic battle, neither side has completely prevailed. Knowing that the other gods now support Baal and fearing El's wrath, Mot finally bows before him, leaving him in possession of the land and the undisputed regent of the gods.

Baal is thus the archetypal fertility deity. His death signals drought and his resurrection, and brings both rain and new life. He is also the vanquisher of death. His role as a maker of rain would be particularly important in the relatively arid area of Palestine, where no mighty river such as the Euphrates or the Nile existed.

#baal#baal deity#baalism#canaanite gods#canaan#ancient history#ancient gods#history#ancient god#spiritual#deity#deities#religious#religion#religia#ancient religion#ancient world#gods#myth#mythos#ancient myths#mythology#mythology and folklore#myths#Canaanite religion#world religions#world history#ancient mythology

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

was supposed to get this section of my capstone done yesterday but i don't have the meeting abt it until monday so i was gonna write it tonight but i just spent like 6 hours writing one tiny section of that section.........

#im TIRED OF THIS GRANDPA#i work tomorrow but ig i will just. write the rest of this tomorrow bc it is already midnight and my brain is so fried#it hasnt helped that my cat has been screaming nonstop for hours i cannot concentrate <3#but it's supposed to be on shared deities/heroes between canaanite religion & the tanakh#and it's going to be. el/yhwh baal danel and asherah#but i only got the el/yhwh section done imfasdfsdf scream#idk why it took me so long i think the problem is i know what i want to say and i have all the knowledge i just have to dig around to cite#bc i read too much and did a bad job keeping track of where i read what which is extremely annoying

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Just found out about the ancient Canaanite pantheon, this explains so much

#ancient canaanite pantheon#ancient Canaanite religion#yeah that explains why catholicism is like that

4 notes

·

View notes