#captain frederick marryat

Text

They should stop having sad soggy pathetic boat men tournaments and start having Smug Obnoxious Jerk Boat Man tournaments. I nominate all of Captain Marryat's protagonist characters and also Marryat himself.

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#i'm thinking about#frank mildmay#jack easy#percival keene#i like to pretend i live in a world where people know marryat and his works

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

Whenever the wind is foul, which it now most certainly is, for I am writing any thing but “Newton Forster,” and which will account for this rambling, stupid chapter, made up of odds and ends, strung together like what we call “skewer pieces” on board of a man-of-war; when the wind is foul, as I said before, I have, however, a way of going a-head, by getting up the steam which I am now about to resort to — and the fuel is brandy.

— Frederick Marryat, maybe being a little too honest in the middle of Newton Forster.

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#newton forster#writing#19th century literature#alcohol#tbh these asides are some of my favourite parts of his writing

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

in honour of and apologies to @marryat92

as generated from neural network ai midjourney

more information at @teuthisdreams

#captain marryat#frederick marryat#cad commits neural network crimes#neural network generation#neural network art#midjourney#shipposting

107 notes

·

View notes

Text

putterings, 256-254

dance of the wreck apophony eye

blue cap and pale sleeves certainly not chairs

the ball as it fell when the rain came, Spain

—

puutterings | their index | these derivations | 20230203

0 notes

Text

Buddha's Foot

Date

18th C–early 19th C

Medium

stone, glass, bitumen & gold

donated by Captain Frederick Marryat, 1826

The British Museum

83 notes

·

View notes

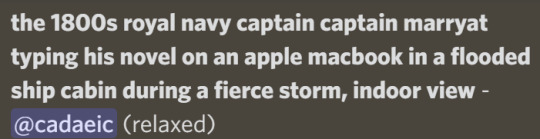

Photo

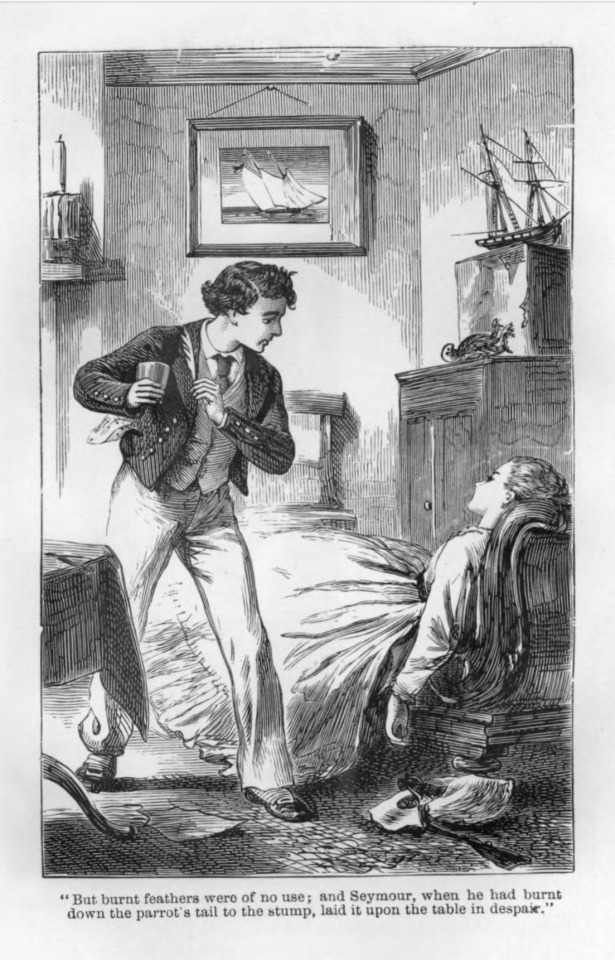

Book illustration for Mr. Midshipman Easy written by Captain Frederick Marryat

"Midshipman Easy, Page 173 - "Oh Mr. Easy, Please Forgive Us". by unknown

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Sailor's Life at Sea (Resources)

It has rather occurred to me that some of our sailors and observers may not be so well versed in the life on board a naval Man o' War, and so I shall reserve this post for the collation of links and resources that may prove useful in the upcoming weeks!

I would also like to... gently is not such the term for it, but to bring your attention to the deadline of the first Action Report's submission to tomorrow at Monday 20th of July GMT 12am / GMT+10 10am. I do promise to be far less bothersome in the following weeks, but as you can imagine, this being our very first report, there is no small amount of worry and excitement on my behalf!

But yes, let us proceed. I shall be citing the works of @ltwilliammowett, a fantastic naval history web log dedicated to charting the unknown waters of history. Reading these are by no means required, but it may enrich your understanding of the world of this game - but of course, you do not need to be entirely accurate, for this is but a game!

--------------------------------------

Masterlists

Here is a masterlist of various posts about a sailor's life in general

A masterlist of posts about sailors' superstitions

And a masterlist about medicine in the age of sail

The various crafts and handiworks associated with the sea

Ranks or people on board

Naval slang

Posts

A day aboard a man of war

Weekly duties aboard a man of war

A post about the etiquette in the wardroom, where the commissioned officers and the wardroom warrant officers ate and socialised

Games played on board

Punishments

Combat between Men o' War

-----------------------------------

Other Links

Another blog I heartily recommend is @marryat92 for excerpts from the works of Captain Frederick Marryat, a naval captain who fought in the Napoleonic Wars and wrote novels inspired by his experiences! These give quite a good impression of the life and times of the world that Shipshape is set in, as accompanied by quite suitable art

This is a glossary of Age of Sail terminology

This is a fansite for Age of Sail fiction with some information and resources

Living Conditions in the 19th Century U.S. Navy

If one would like to peruse some books, I also recommend:

The wooden world: an anatomy of the Georgian navy by N A M Rodgers

Stephen Biesty's Cross-Sections Man of War (a very colourful illustration of the setup of a man of war!)

-----------------------------------

This post will be edited and updated as your humble ship's clerk organises the captain's library.

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

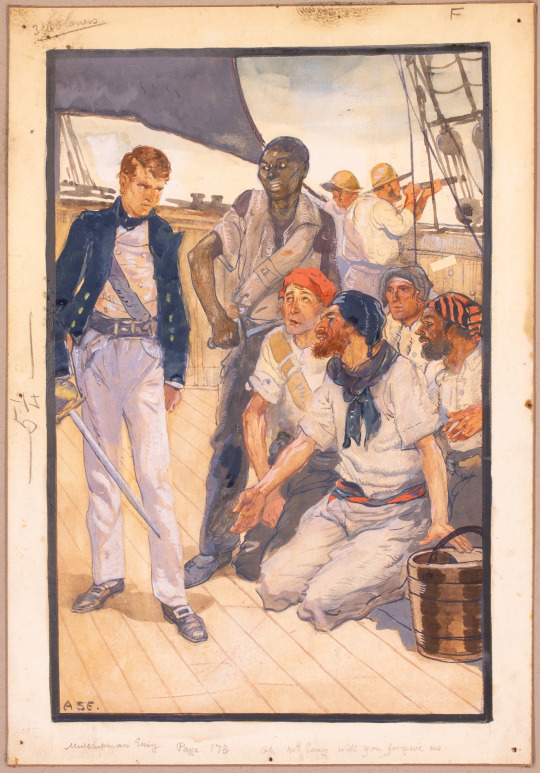

Fitz Flute

About Graham Gore Fitzjames said that "he plays the flute dreadfully well"

Apparently Fitzjames owned a flute as a teenager but never had much time to actually play it. He took it with him on the HMS Pyramus and HMS St Vincent.

After that we hear no more of the flute.

[Detail from: The Interior of a Midshipman's birth, 1821 Print, after Captain Frederick Marryat, British Museum]

Fitzjames mentions the flute in a few letters:

HMS Pyramus June 29th 1826

Dearest Uncle

You no doubt expected a letter from me yesterday but I could not get on board till to day — so I did not write — I arrived quite safe at Portsmouth on Tuesday Morning, but when I got here I had to pay 10 Shillings for they said that when I was booked you only paid 10 Shillings. I told them that I paid a sovereign & they kept my luggage till I had paid it — I forgot the ink Powder but got every thing else quite safe — Mr Sterling got me a very nice flute indeed and I have got it quite safe

-----

HMS St Vincent Decr 20th 1830

My Dear Uncle

I am now comfortably on board, and am a little more accquainted with my messmates some of them, indeed all of them, are very nice fellows, and I think I shall be very comfortable. I have a good birth for my desk, and one of the mates has allowed me to keep my flute and several other things in his cabin.

----

To William Munn [a friend/neighbour from Blackheath]

In the Bosphorus HM Cutter Hind

April 10th 1832

[...] The flute gets on slowly as I have not much place & time to play. You must be quite a professor by this time.

[Detail from: 'Master B finding things not exactly what he expected', the midshipman arrives on board ship; study for an illustration to 'The Life of a Midshipman', 1820 Drawing by Captain Frederick Marryat, British Museum]

Thanks @marryat92 for pointing me to these wonderful illustrations

#james fitzjames#royal navy#franklin expedition#the terror#the terror amc#history#letters#graham gore#flute#frederick marryat

63 notes

·

View notes

Note

Please recommend me some more accounts like yours :)

Eſsteem'd Anon,

Thank you for the compliment! I am happy you like my account, and are looking for more content like mine.

Which raises the question, what is my account? Perhaps you could clarify which type of content in particular you're interested in, because I feel that, rather than coordinated, my blog is all over the place. Are you here for my occasional pictures from pretty places? My posts about a certain naval gentleman of the 18th century? Stuart memes? The Flight of the Heron, or the novels of Marjorie Bowen? The odd talk about my fiction writing?

Given I am but a magpie who just adds whatever shiny thing (mostly tinfoil, I fear) she has found to her humble online-nest, I feel my blog is not coordinated enough to give a clear reply.

If it's predominantly European and/or North American history of roughly the 17th to early 19th century you're looking for, here are my recs, ascending by era:

@nellgwynn (lots of humourous Stuart-centric content)

@vankeppel (the Stuarts, the British generals and loyalists of the American Revolutionary War, Arctic exploration)

@nordleuchten (American Revolutionary War and French history of the early 19th century, an authority on the Marquis de La Fayette and George IV; also the host of @pitt-able, concerning William Pitt the Younger)

@pentecostwaite and @benjhawkins (local maritime history of Maine, and working at a local history museum/historic house)

@anarchist-mariner (commentary on the Rebellion of 1798, political history in the British Isles in the late 18th/early 19th century)

@clove-pinks/ @marryat92: (War of 1812, various aspects of 19th century life, and the novels of Captain Frederick Marryat)

I hope this helps!

I am, &c.

-R.

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

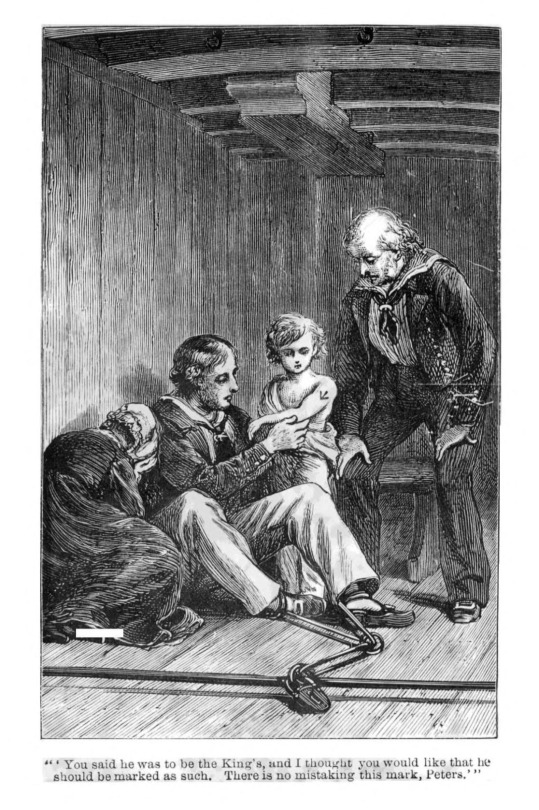

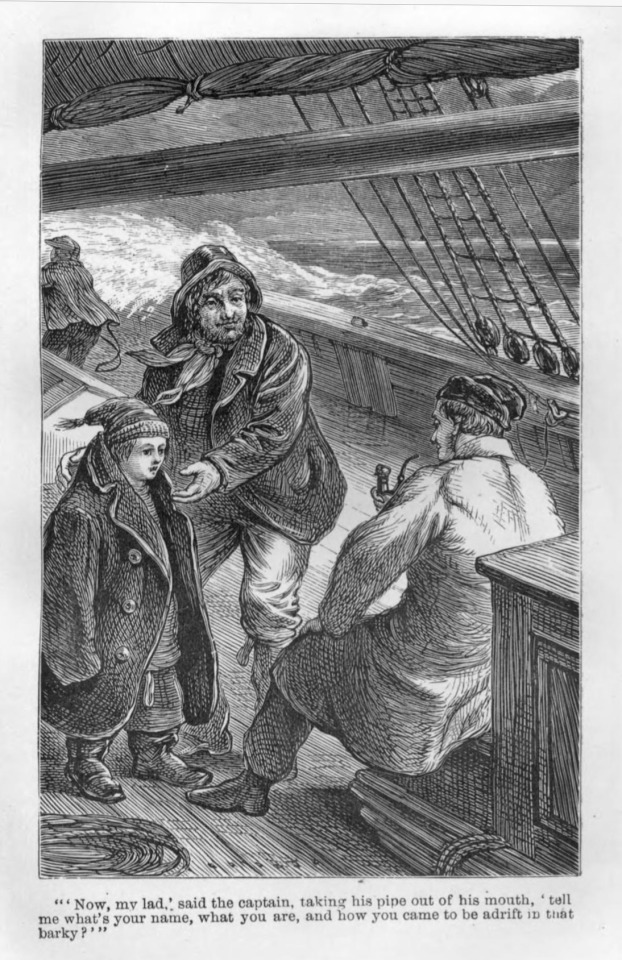

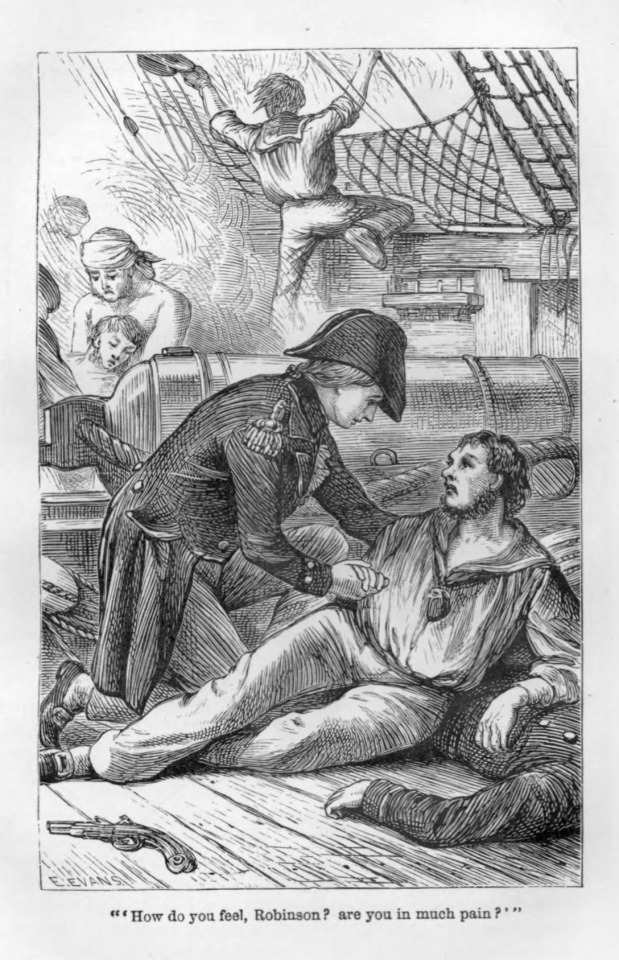

THE KING’S OWN by Captain Frederick Marryat. (London Macmillan, 1896) Illustrated by F.H. Townsend. Cover designed by A.A. Turbayne

another edition here

#beautiful books#books books books#book blog#book cover#books#illustrated book#vintage books#nautical#adventure#victorian era

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

"For many boys growing up in England in the eighteenth century the Royal Navy was immensely glamorous, the object of intense fascination. Naval heroes such as Drake, Hawke, Anson and Rodney were widely celebrated in popular songs, cheap broadsheets, chapbooks, memorabilia and even pub signs. There was almost universal agreement that the navy was Britain’s own particular strength, and that unlike the army, the navy defended the country and promoted trade without threatening traditional English liberties. Even in peacetime there were naval exploits to capture the imagination, such as Captain Cook’s voyages of exploration, which made him a celebrity not only throughout Britain, but across all Europe.

Boys were captivated by stories – fictional, semi-fictional and true – of life and adventure on the high seas, most notably by Robinson Crusoe, which found a wide and appreciative audience throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. A career at sea, especially in the navy, appeared exciting, romantic and desirable; and there were numerous cases of young boys either running away to sea or demanding that their parents allow them to join the navy. Matthew Flinders and Lord Cochrane both overcame their father’s opposition and joined the navy; while Francis Austen, William Light and Frederick Marryat successfully urged their parents or guardians to allow them to follow their inclination.

Of course, not all boys joining the navy did so with eager enthusiasm, but of all the careers open to young gentlemen, this was clearly the most popular with the boys themselves, at least until Wellington’s victories in the Peninsula allowed the army to claim a share of the limelight. Many parents favoured the navy as a career for their younger sons on more pragmatic grounds. It was traditional, patriotic and thoroughly respectable; it took boys when they were young – usually 13 or 14; and it was cheap, with no need to pay school fees or to purchase a commission, as in the army.

The parents or friends of a young gentleman sent to sea would still normally give him an allowance, usually between £30 and £50 a year, although some young midshipmen were forced to live on nothing other than their pay and rations. This allowance might be a considerable drain on the resources of a poor clergyman or half-pay army officer with a large family, but it was still one of the most affordable ways of establishing a boy in a suitable career. It was also a particularly tempting solution for the parents of a wild or troublesome youth, who might hope that his high spirits and abundant energy could find a useful outlet aboard a man-of-war.

Recent research by Evan Wilson has shown that only about one fifth of all naval officers came from the landed gentry and nobility; a second fifth had fathers who were themselves in the navy; and most of the remainder came either from the professions or from the world of commerce, although this last category ranged from small shopkeepers to wealthy merchants. As expected, very few came from humble backgrounds outside the navy and most of these remained stuck in the lowest ranks or were only given a commission at the very end of their career.

In other words, naval officers were drawn from the same classes of society as clergymen and lawyers, although they had a rather higher proportion of fathers engaged in commerce than the clergy. Naval officers were also much less cosmopolitan than their crew: most came from England and especially southern England, with the southwest (Devon and Cornwall), Kent, Hampshire and London all being overrepresented, reflecting the location of the principal naval bases and the tradition of seafaring in these parts of the country.

The most common way for a boy of good family to join the navy was as a ‘servant’ to the captain or, less frequently, to one of the other officers on board. Every captain was entitled to have four such servants for every hundred members of his crew – and a ship of the line might have a crew of seven or eight hundred. Some of these would actually be servants, older men with no expectation of promotion, but more than half were embryo officers who would remain under the captain’s authority for at least six years.

The official designation of these boys varied often with bewildering rapidity: any one might be a ‘servant’, a ‘volunteer’, a ‘midshipman’, a ‘master’s mate’, or an ‘able seaman’, without this greatly affecting his role or life on board, although collectively they are best described as midshipmen. The captain was responsible for supervising their education and welfare and would, ideally at least, see that they gained a thorough knowledge of seamanship and navigation.

He would also – again ideally – provide an example of how to manage the crew, maintaining authority with little resort to harsh discipline, and ensure that his midshipmen acquired the manners and general knowledge that befitted their future position as officers and gentlemen. The appointment of such boys was entirely at the discretion of the captain, and captains prized the privilege highly. Young relatives had an obvious claim on such patronage, and so did the protégés of patrons, senior officers and other men of influence.

The connection could be quite tenuous: the young Matthew Flinders was introduced to Captain Thomas Pasley by his cousin Henrietta, who was governess to Pasley’s children; while William Light found a place under Captain Charles Cunningham thanks to the recommendation of his guardian’s son, who was the vicar of Hoxne in Suffolk, near Cunningham’s home. Unlike most forms of apprenticeship captains did not charge the parents of boys a premium for taking their sons off their hands, although it is said that there were cases in which inconvenient tradesmen’s bills, especially in dockyard towns, disappeared at the same time that the son or nephew of the tradesman was taken on board.

A few boys entered the service through the Naval Academy at Portsmouth, which had been established in 1729 with the intention of providing better educated, more rounded, officers. The Academy had not been a great success – captains feared that it would encroach upon their patronage, and there were rumours of idleness, bullying and debauchery, although modern scholars have come to view these reports with considerable scepticism. Francis Austen joined the Academy in 1786 when he was just short of 12 years old, a small boy, full of energy, courage and liveliness, but also intelligent and with a warm heart.

He was one of a dozen new pupils that year, although when his brother Charles followed in 1791, there were only three others in his class. Mr Austen paid £50 a year for each of his sons to attend the Academy, and it proved a useful way for a gentleman with no personal connections in the navy to get his sons into the service. Francis in particular thrived at the Academy, and won high praise for his aptitude, character and behaviour, so impressing Sir Henry Martin, its governor, that he became Francis’s first patron.

One great advantage of the Academy was that it softened the blow of parting for both parents and child: sending a son there was no worse than sending him to any other school, while if he went straight to sea it might be many months or even years before the parents would see him again – a time of real perils and immense change which the parents could only dimly imagine. Leaving home to go to sea the young boy would enter a completely foreign world. If he had not grown up near a port he might be unfamiliar with the sight of a warship.

One officer wrote: never shall I forget the overwhelming and indefinable impression made on my mind upon reaching this wonderful and stupendous floating structure. The immensity of hull, height of the masts, and largeness of the sails, which had been loosened to dry, so far exceeded every anticipation I had formed, that I continued, unmindful of what was going on in the boat to gaze on her in dumb amazement, until awakened from my stupor by the coxswain, who now gruffly exclaimed, ‘Come, master! come! mount a’reevo, ’less you mean to be boat-keeper’. Life on board lacked the restraint and decorum of a parsonage schoolroom or family parlour, and a new recruit was often disconcerted by his shipmates who were seldom interested in putting him at his ease.

James Anthony Gardner recalled that I was shown down to the starboard wing berth. I had not been long seated before a rugged-muzzled midshipman came in, and having eyed me for a short time, he sang out with a voice of thunder: ‘Blister my tripes – where the hell did you come from? I suppose you want to stick your grinders (for it was near dinner-time) into some of our à la mode beef ’; and without waiting for a reply, he sat down . . . While another young man recalled that at first he did not know if this new world was inhabited by devils or spirits, ‘All seemed strange; different language and strange expressions of tongue, that I thought myself always asleep or in a dream, and never properly awake’.”

- Rory Muir, “The Navy: Young Gentlemen at Sea.” in Gentlemen of Uncertain Fortune: How Younger Sons Made Their Way in Jane Austen's England

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s Frederick Marryat’s birthday very soon (10 July 1792), and I’ve been thinking a lot about the effect he’s had on my life: and just what is the nature of my fascination with this man. I think a huge part of being interested in Marryat is being drawn to the man himself, not just his stories and travel writing. You have to have some kind of personal investment in this bitchy, lecherous, sarcastic, self-righteous, frequently infuriating and problematic man; you have to care about him on some level. He feels extremely present in his writing.

I think Virginia Woolf expressed it well when she wrote in her essay on Marryat, “The Captain’s Death Bed”:

Often in a shallow book, when we wake, we wake to nothing at all; but here when we wake, we wake to the presence of a personage—a retired naval officer with an active mind and a caustic tongue, who as he trundles his wife and family across the Continent in the year 1835 is forced to give expression to his opinions in a diary.

Sometimes I wonder about what Marryat would think of me as his reader. In response to criticism in Fraser’s Magazine, Marryat wrote a long letter defending his work in cheap weekly newspapers which would be read by the lower classes (reproduced in The Life and Letters of Captain Frederick Marryat, edited by his daughter Florence Marryat). He starts out strong, attacking elitist attitudes about literature, and then shows his ass with smug pronouncements about how he’s writing wholesome fare to educate the lower classes, unlike trashy weeklies filled with “immorality and crime” that also teach people to criticize the government or read Chartists! (Marryat was a complex person whose views can’t be pinned down with modern political labels, but he wasn’t very progressive, not even in his own time.)

Marryat was my introduction to the Napoleonic Wars and the War of 1812, which have become major interests, he was my first real exposure to Regency-period fashion and manners, and he has increased my general nautical knowledge a hundredfold. I feel a kinship with him across time and space as he offers his opinions on the world of the 1830s and 40s, a bit jaded in middle age but still keenly observant and very confident in his opinions.

#frederick marryat#captain marryat#shaun talks#he's one of those 'i wish i could study him in a jar' types (and i'd shake the jar too)#but i feel bad for him#this man was at war for a billion years starting from childhood#and it definitely messed him up#and he can be a genuinely good storyteller#complicated feelings for a complicated man#i will admit to liking marryat

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

As the night advanced, so did the wind increase and the sea rise; lightning darted through the dense clouds, and for a moment we could scan the horizon. Everything was threatening; yet our boat, with the wind about two points free, rushed gallantly along, rising on the waves like a sea-bird, and sinking into the hollow of the waters as if she had no fear of any attempt on their part to overwhelm her.

— Frederick Marryat, Poor Jack

Storm at Sea, French School, 18th century (Art UK)

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Naval Officer Frank Mildmay

"I was now in my twenty-second year; my figure was decidedly of a handsome cast; my face, what I knew most women admired. My personal advantages were heightened by the utmost attention to dress; the society of the fair Arcadians had very much polished my manners, and I had no more of the professional roughness of the sea, than what, like the crust of the port wine, gave an agreeable flavour; my countenance was as open and as ingenuous as my heart was deceitful and desperately wicked."

-- Frederick Marryat, Frank Mildmay, or The Naval Officer

generated from the text prompt

"young proud handsome arrogant smirking Royal Navy naval officer"

and image prompts of:

the naval novellist captain frederick marryat

and a picture of ioan gruffudd as hornblower

using the neural network AI midjourney

with a few edits and tweaks post-generation

with thanks and inspiration to @marryat92

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mr. Midshipman Easy

Captain Frederick Marryat (July 10, 1792-August 9, 1848) was an English Royal Navy officer, a contemporary of Thackery, and an acquaintance of Charles Dickens. He is known today as an early pioneer of the sea story. Based on Marryat’s adventures sailing with Lord Thomas Cochrane during the Napoleonic Wars, “Mr. Midshipman Easy” (1836) is mostly a humorous, sometimes ironic, satirical, seafaring…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Alredered Remembers London-born English naval officer and adventure novelist Captain Frederick Marryat, on his birthday.

“White lies are ushers to black ones.”

-- Frederick Marryat

0 notes