#cathy park hong

Text

Thinking about these tweets

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

"The most damaging legacy of the West has been its power to decide who our enemies are, turning us not only against our own people, but turning me against myself."

Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning

#im not crying youre crying#sriracha reads#minor feelings#cathy park hong#assimilation#asian american#racial trauma#colonialism

29 notes

·

View notes

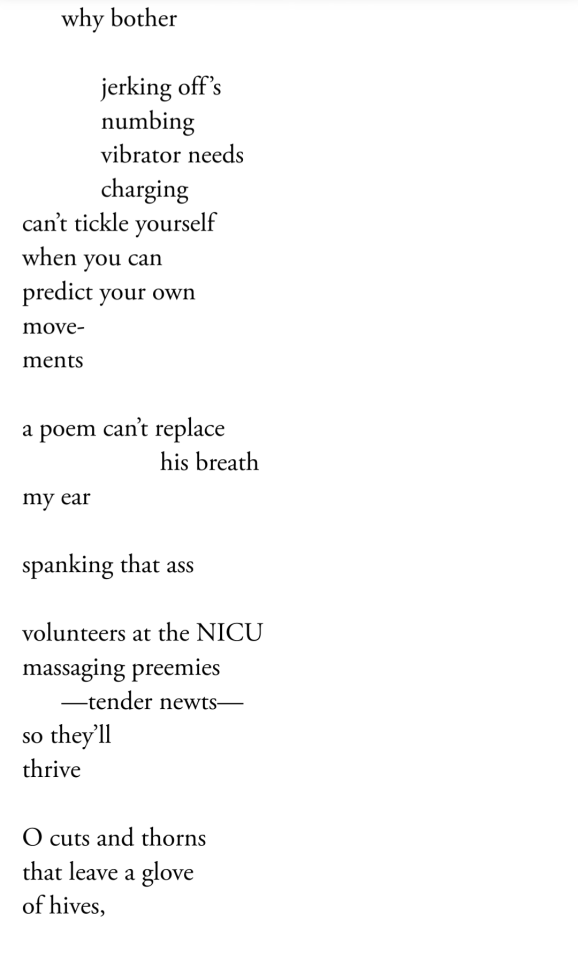

Photo

Cathy Park Hong, Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning

38 notes

·

View notes

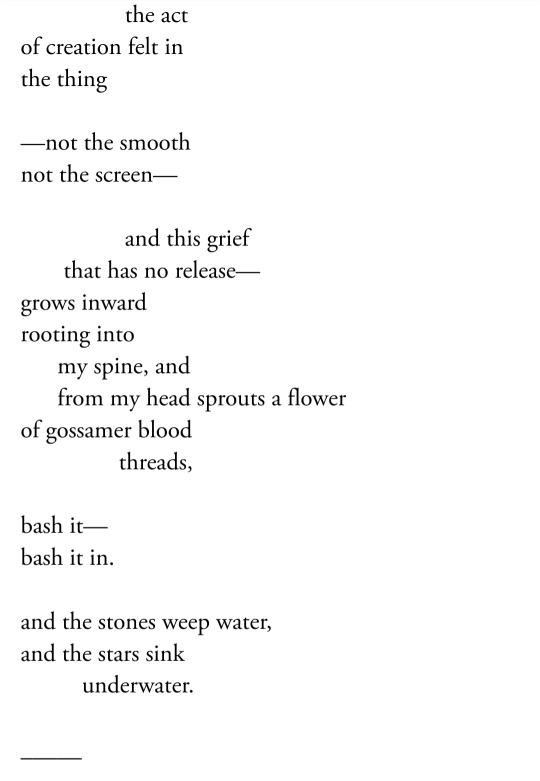

Photo

24 notes

·

View notes

Link

It’s a fact that more artists and writers tailor their works with the Internet viewer in mind. There are artists who make trendy abstract paintings in bold, unmodulated colors so nothing is gained or lost when one sees them on Instagram or in the gallery; these paintings are as easy to apprehend online as a color swatch for a sofa, which is ideal for the collector who doesn’t have time to experience the product in person. Similarly, there are more writers who write with transparent compression, knowing that their phrases could be atomized into tweets, chiseled into self-sufficient, endlessly linkable fragments.

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

Exploring MINOR FEELINGS: A review

Published Sunday, August 7th, 2022 — About halfway through Cathy Park Hong’s Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning, I felt a brief embarrassment at how I was almost desperately picking out passages that mirrored my own thoughts and experiences, quickly followed by a bout of indignation that I should feel embarrassed at all for being excited to find something I could relate to in someone else’s writing. After almost an entire lifetime of reading “classics” and bestsellers written by predominantly white authors, could I not enjoy this triumph in which both the author and reader could share? Is Cathy Park Hong going to appear in my bedroom and accuse me of grasping at straws for similarities between her life and mine?

Introduction

While confined to my home for about three months at the beginning of 2020, I swept through a long list of books but found myself unable to keep up the habit into 2021 and 2022—even though I was still buying books whenever I saw a title and plot synopsis that sparked my interest. Although I have always been close to my culture and have kept my Koreanness hugged tightly to my identity and sense of self, I decided that I would put my money where my mouth is and actively support Asian and Asian American authors by buying their books. At the beginning of July, discovering a new supply of spare time after starting to work from home, I gathered all of the books by Asian and Asian American authors that I had received as gifts or purchased over the past year and made a commitment to myself to read all of them. Gifted to me for my 27th birthday by a friend, Minor Feelings was among the nine books I had yet to read—and one of the shortest—so I started reading.

How Minor Feelings Sparks Some Not-So-Minor Feelings

The book follows what Hong calls an “episodic form, with its exit routes that permit me to stray” (page 104), which means that there is no glue holding a timeline together, only individual vignettes whose order in the fabric of Hong’s experiences may elude everyone but Hong herself. I often found myself nodding in agreement unconsciously at certain things Hong said or anecdotes she shared. She has a sense of humor that I quite like, a brash-bordering-on-inappropriate kind of funny that I myself don’t indulge in but like to hear in other people. Not too far into the book, on page 31, however, Hong includes a passage on how during the Korean War, her grandfather had been dragged out of his home by U.S. soldiers for being a suspected Communist collaborator—and I cried. I cried and I cried and I cried. My mother had been born the year following the Korean War’s end, which means that my grandmother and my mother’s older siblings had all lived during that time. It was hard not to imagine my grandmother in Hong’s grandfather’s place and it was some time before I was able to pick the book back up and keep reading.

“Minor feelings” are, as Hong says, “the emotions we are accused of having when we decide to be difficult—in other words, when we decide to be honest. When minor feelings are finally externalized, they are interpreted as hostile, ungrateful, jealous, depressing, and belligerent, affects ascribed to racialized behavior that whites consider out of line” (page 57). Racial oppression is, to put quite bluntly, not a competition; and all people of color acutely feel the experience of being told that they are too much when they speak up against a system that seeks to only benefit those who created it. But the truth—or at least my truth—is that Asians are the only ones deemed still safe to mock, still safe to harass, still safe to attack in public and get away with it. Being Asian in America means being cast to the side because our supposed white adjacency affords us a protection that other minority groups don’t have, when the truth is that we are working far too hard to please white people who don’t care about us at all. The same way that many Asians align themselves with whites for the benefit of their nonexistent protection, the result of that misplaced trust is that now we are being targeted and blamed by other groups eager to no longer be the most hated people, not realizing that their behavior is not earning them protection from whites either. And I think that there are people—quite a lot of people, in fact—that may find it distasteful for me or anyone else to say so out loud. “Why do you hate white people, Liz?” is a question I get often—and all I have to say is “Why aren’t you more upset about the fact that the system created by white people makes it difficult for the rest of us to succeed?” White people, particularly white men, can pass off mediocrity as the standard and thrive—but people of color, we will always be fighting tooth and nail for the chance to have our work recognized. (For the record, I feel it’s important to state that I don’t “hate white people”, but I find that the question is also a reaction to me sharing my minor feelings because the other person is uncomfortable with how comfortable I am in refusing to stay put in the boxes that the system created by white people would love to keep me in.)

Minor Feelings and the Current Sociopolitical Climate

With the shared trauma of being the scapegoat for the COVID-19 pandemic, Asian Americans and other Asians living outside of their home countries are experiencing a reclamation of their cultures, their identities, their Asianness. We’re showing a renewed interest in our parents’ language, food, and customs—a desire to travel to our home countries, immerse ourselves in the culture that we may have taken for granted in our youth. But Hong brings up an excellent point: As artists, as filmmakers, as writers, does all of our work have to be framed as “the Asian experience”? Can my stories simply be stories and not “stories about the Asian experience”? Can I write without having to worry about whether white people understand where I’m coming from or whether I’ve hurt their feelings with my criticisms? Can my value as a writer come from the quality of my writing and not how well I can translate “the Asian experience” into something that is palatable and inoffensive enough to be popular?

The last two chapters of Minor Feelings were particularly difficult to read, opening up space for discourse on topics that people would rather avoid. Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, a thirty-one-year-old artist and poet, was raped and murdered in New York on November 5, 1982. And while her work was celebrated and continues to be celebrated, her homicide received minimal media coverage and neglects to also be labeled as rape. I’ve been told that Asians don’t suffer as much as other minority groups in the United States, that we have good lives here—but that’s just what the majority wants people to believe. Sexual assault among Asian women is severely underreported and therefore statistics, let alone accurate statistics, are hard to come by. Internalized shame as a result of trauma is so culturally rooted that we refuse to speak up and then in turn, the rest of the world turns a blind eye. “She was just another Asian woman,” Cha’s close friend said when asked why there was no media coverage of her rape and homicide. “If she were a young white artist from the Upper West Side, it would have been all over the news” (page 176). To this day, no one wants to talk about Cha’s death for fear of overshadowing the impact of her work, but in doing so, we are making it easier to pretend that these things don’t happen—that they don’t exist—and therein does the rest of society make it acceptable for us to be targeted without repercussions. “From invisible girlhood, the Asian American woman will blossom into a fetish object. When she is at last visible—at last desired—she realizes much to her chagrin that this desire for her is treated like a perversion. [...] [But] the Asian woman is reminded every day that her attractiveness is a perversion, in instances ranging from skin-crawling Tinder messages (”I’d like to try my first Asian woman”) to microaggressions from white friends” (page 174-175).

Hard Pills to Swallow

Hong’s work can be taken for what it is: a series of written episodes about exploring what it means to be Asian American and how it can differ from person to person. It talks about the negative truths that we must acknowledge and the silly things we later learn caused us more stress than they were worth, the sadness we carry as a result of our feeling like outsiders and the joy we savor when we make progress in this messed up universe. We’re all still carving out our identities and our places in this world, in this society. “Even if we’ve been here for four generations, our status here remains conditional; belonging is always promised and just out of reach so that we behave, whether it’s the insatiable acquisition of material belongings or belonging as a peace of mind where we are absorbed into mainstream society” (page 202). In the end, neither she nor any other Asian American writing about similar topics is trying to convince you of anything. You either get it or you don’t. Contrary to what racial fetishization and general ignorance might have you believe, being Asian in America is not so much an enigma as it is one of those things that gets swept under the rug because our minor feelings have been internalized for so long. I didn’t need to read Minor Feelings to know this, but reading it made me more tangibly aware of it. Being Asian in America means being treated poorly and then being told to be grateful because we could be getting treated much worse somewhere else—and by the way, if you don’t like it, then why don’t you go back to where you came from?

“Then be grateful that you live here. [...] I bring up Korea to collapse the proximity between here and there. Or as activists used to say, ‘I am here because you were there.’ I am here because you vivisected my ancestral country in two. In 1945, two fumbling mid-ranking American officers who knew nothing about the country used a National Geographic map as reference to arbitrarily cut a border to make North and South Korea, a division that eventually separated millions of families, including my own grandmother from her family. Later, under the flag of liberation, the United States dropped more bombs and napalm in our tiny country than during the entire Pacific campaign against Japan during World War II. [...] My ancestral country is just one small example of the millions of lives and resources you have sucked from the Philippines, Cambodia, Honduras, Mexico, Iraq, Afghanistan, Nigeria, El Salvador, and many, many other nations through your forever wars and transnational capitalism that have mostly enriched shareholders in the States. Don’t talk to me about gratitude” (page 193, 195).

Conclusion

Hong writes about a former friend, “This was the most Korean trait about her, her intense desire to die and survive at the same time” (page 146). In that line, I found solidarity. In Hong’s writing, I found solidarity—and if there is anything that I think should be taken away from Minor Feelings, it’s that we are going through a shared experience, a collective trauma but also a collective movement towards loving ourselves for who we are and recognizing that we deserve to exist wherever and however we choose to exist. I shed more tears during the reading of this book than I expected to, but shared trauma brings people together in many ways. I think that Minor Feelings is meant to both comfort and discomfort, to hit you in all the right places and all the wrong places. For every Asian person out in the world who felt that they couldn’t be someone, that they couldn’t do something—for every Cathy Park Hong who felt like they shouldn’t write a book just like this, though our experiences may differ, there are some things we all share; and we must be our greatest allies.

#GeniusLabReads#Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning#Minor Feelings#Cathy Park Hong#AAPI Literature#AAPI#Asian American Literature#Asian American#Book Reviews#TW: Rape#TW: Homicide#TW: Violence

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

weekend read / 6.2022

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Best of 2023 Reads: Poetry -

From sacred texts and opera librettos to contemporary and politically intimate free verse, here are a few of the works that stood out in 2023!

#bookworm#literature#book reviews#read read read#books#best of 2023#poetry#maggie nelson#eileen myles#natalie diaz#christopher soto#tyehimba jess#cathy park hong#alice goodman

1 note

·

View note

Text

"If the indebted Asian immigrant thinks they owe their life to America, the child thinks they owe their livelihood to their parents for their suffering."

Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning

#that hit me#sriracha reads#minor feelings#asian#asian american#familial trauma#racial trauma#cathy park hong

10 notes

·

View notes

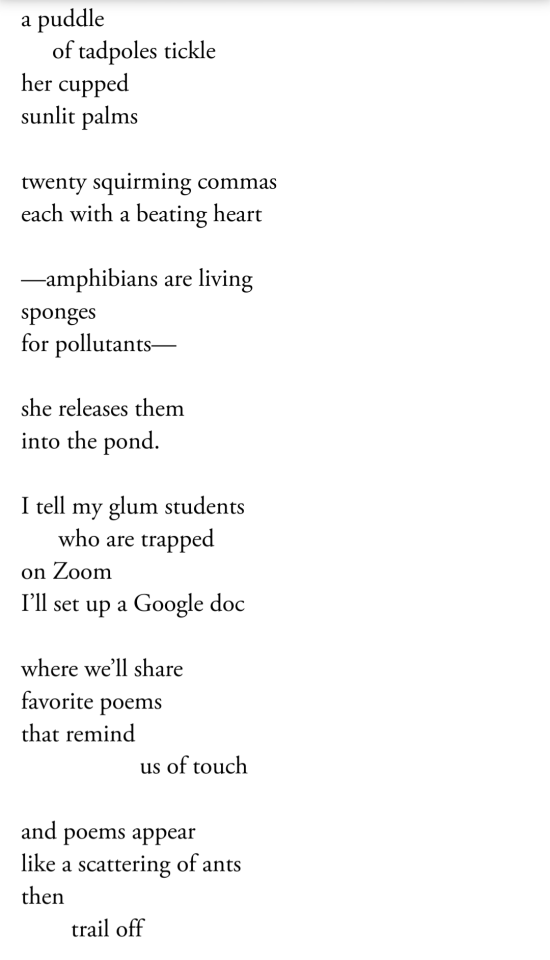

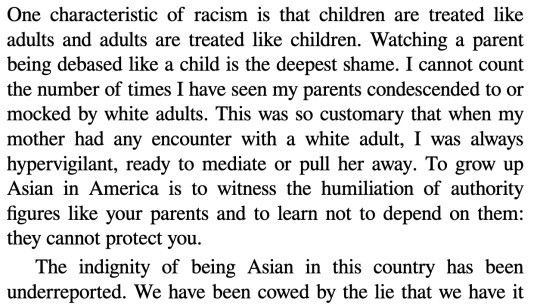

Photo

Cathy Park Hong, Minor Feelings: An Asian American Reckoning

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Days

Garçon, you snore so rhapsodically but hup hup,

peach schnapps & Coke Zero

with a gumball-green mermaid swizzle stick—

I need me a diabetic shock.

I yearned so long to be ensorcelling,

yet I’m always a meter maid, never a mermaid.

I’d populate this world w’ idlers of my kind,

but pistil-less, I’m pissily only one.

Who made me this way? Oh you. Oolong Ma.

(Go bury yourself in a sandpit, Ma,

while my galpals and I split a cranmuffin 5 ways

and watch.)

So here I gig, in this club empty

as a tampon dispenser inside the shell

of a Texas gas station—still

I’ll stand, declaim:

Not enough letters in my soup, garçon!

All I’m doing is inging

like an atting instrel,

I’m rank when I need to be frank!

Just you wait, I’ll hijack all type—

My specialty? Scandinavian Modern

Pinkface.

– Cathy Park Hong

0 notes

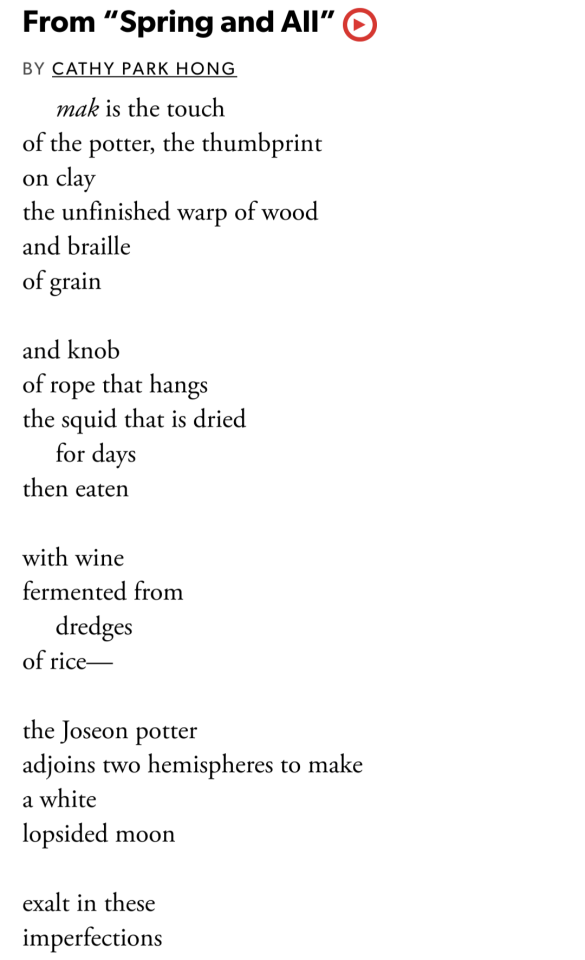

Photo

an interesting read

0 notes