#cavalieredispade

Text

Charles and John sketch

#charles smith#john marston#rdr2#sketch#sketchbook#drawing#red dead redemption#rdr#red dead redemption 2#cavalieredispade#cavalieredispade art

521 notes

·

View notes

Text

yep

new blog name

marianaillust.tumblr.com

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

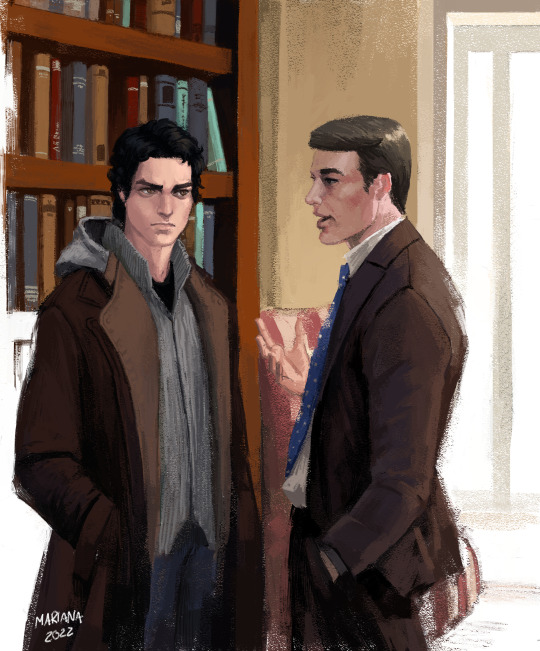

Insult to Injury: The Director’s Cut — Chapter 05 [Revised]

(Chapter revised as of 02/17/23)

Commissioned illustration(s) by cavalieredispade, who can be found on tumblr & instagram.

— ACT II —

“From my rotting body, flowers shall grow and I am in them, and that is eternity.”

― Edvard Munch

V: НО НА МЯГКИХ ПОСТЕЛЯХ НЕ УЗНАЛ Я ПОКОЯ

ПОТОМУ ЧТО ВО СНЕ ЭТА ПТИЦА КРИЧАЛА

Eyes on the pale green wall ahead. The doctor and a few nurses crowded around the boy two beds away. Still unconscious. He squared his shoulders and resisted the impulse to rub his forearm. Shirt torn at the collar. Spattered with blood, as was the towel across his lap. His clothes and bookbag were all inherited. Donations from benevolent outsiders. He tongued around for a loose tooth. Just a busted lip. Could be worse.

“Keep an eye on this one,” the head nurse said to the junior. “I’ll speak with the doctor about the other boy.”

Eleven years shuffling between state-run boarding institutions and public school taught Safin how to be his own man. That a lack of parents was also a loss of insurance, and the way to survive was becoming obedient and invisible. So he didn’t get slapped around or humiliated as much as kids who weren’t so observant. Some adults didn’t need an excuse to enact cruelty. Most were just doing what they thought was right. They employed older, bigger kids without scruples as proxies for discipline.

A lot of kids had one living parent but nothing to do with each other. The kids who tried to leave got rounded up into a truck and taken to psikhushka, sharing meals and cells with adults too hostile or hopeless to rehabilitate. Kids who were dosed with aminazine as babies to help them sleep, now they were dealing with liver problems and disappearing to internat. Soon another kid took their place. Everything was done for a good reason.

At fifteen, Bronev was old enough to join a technical institute. Unteachable in a classroom but cunning and ruthless enough to do the bidding of the staff in return for preferential treatment. He’d have a bright future on the streets as a runner for firearms or heroin. He also had a knack for picking out the smaller, weaker kids the adults had no time for, and giving them attention and praise. Pretty soon, these kids would do anything to stay friends.

Safin had no immediate loyalties to anyone. But he kept on good terms with Bronev by stealing for him. He was smaller for his age, and his face accentuated a boyish appearance he could not outgrow. So he could be eleven or eight years old, which helped when imploring strangers for money or pickpocketing.

Kids who cooperated received a cut of the money. Bronev usually had a couple of impressionable boys at his heels, ready to do whatever he asked. There were also a small handful of kids who showed up to school with bruises. They’d flinch if Bronev said hello. No one was going to stick his neck out.

Bronev would rap him on the back of the head with his knuckles, but he would also accompany him to and from school and the dyet dom for protection.

Earlier today, he requested Safin to steal some power tools from the school’s hardware storage. Safin couldn't say, why don’t you find someone else, because Bronev would wait up for him in an empty classroom or abandoned dorm room with a couple friends and they’d get even. So he said, “The stuff in there is not worth much.”

“Yeah, but there’s good money in selling used car parts. The tools in there, we can use them. Or sell them.”

“Those guys on the black market aren’t interested in dealing with anyone but each other,” Safin said. “The school will notice equipment is gone. It’s not worth the trouble.”

Bronev insisted he had always looked out for him, and this wasn’t fair. But if Safin was serious about turning down this offer, he had to pay up somehow. “What about that book?”

The one possession Safin could call his own, purchased with his cut of pocket money. The culmination of visiting the school’s library for a year, transcribing diagrams from older textbooks and their entries in Ukrainian and Russian. “It’s not for sale.”

Bronev pointed out it was purchased with someone else’s money. So really, the book was not his. He should do the right thing and hand it over to the adults, and apologise for his wrongdoing. Or there could be serious consequences. If Safin yielded he could never make up for his mistake. He’d gotten in a handful of fights, usually outnumbered or overpowered. He only won by fighting cheap.

It wasn’t personal. It wasn’t about the money either.

By the time they were brought to infirmary, Safin didn’t feel a thing. The head nurse grabbed his arm and steered him to an empty bed and had him sit. All he could taste was blood. A younger nurse was there to restrain him if need-be. While the head nurse dressed his wounds he didn’t flinch, or make a sound. He glanced at the younger nurse, who recoiled slightly but said nothing. Most adults did not flinch.

The orphanage director came down to discuss the situation with the doctor. As Bronev was still unconscious, the director asked Safin about what happened. Safin explained he had been coerced for weeks, and simply defended himself.

“And what can you tell me about this?” The notebook. The orphanage director thumbed through a few entries.

Abrus precatorius. Native to Asia and Australia. A single seed contains abrin which can be crushed into yellow-white powder, dissolved in water or ingested. Effects are similar to ricin. No antidote.

Digitalis. Native to Europe, west Asia, northwestern Africa. Formerly used to treat epilepsy and other seizure disorders. Intoxication can induce headache, gastrointestinal disturbances, cardiac arrhythmias. No antidote.

Eucalyptus. Native to Australia. Leaves and bark are poisonous. Handling them can cause skin redness, irritation, and burning. Ingestion; nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, coma. The oil is extremely toxic if ingested.

Ricinus communis, found in the waste left over from processing castor beans into oil. Induces respiratory distress, fever, nausea, pulmonary edema.

Safin said, “I've always been curious about the flora outside of Russia. I figured it would be useful to teach others what to avoid.”

The director and doctor deemed him troubled, but educatable. Safin got shipped to a boarding school in Serafimovka, in the Urals. Boys who stole cars or got into violent altercations. He could still take vocational training at fifteen. There was a Pedagogical Technical Directorate several hours northeast of Moscow.

He was afforded a tutor and a rigid schedule. He sat with his back to walls during meals, or at-rest, always with a door in-sight. He made acquaintances, but preferred to work alone. His ruthless tendencies curbed without a need for demonstration.

At fifteen, he applied for and transferred over to Suvorov Military Academy in Kazan, where he spent the next three years with his sights on border security.

Out of all the instructors, his favourite was Tovarisch Colonel. The drab military coat buttoned to her throat accentuated her squarish face. Auburn hair secured in a tight bun. She addressed all the students by surname and responded only to correct military address. Rumours passed down about her previous military service, as well as the bloody smock and low camp-stool in her office, kept on display.

His lack of words must first imply stupidity. This was disproved by his knowledge of floriology, toxicology. Then she would order him to take documents to other instructors. He did not say a word, simply jumped at the chance to make himself useful.

She told him once, “I am not interested in a prodigy, nor an abject failure. The best soldier appears average. Unremarkable. He appears to make a mistake, but it is entirely of his own volition.” More gradually, she began posing harmless inquiries. Needling out details from his childhood. “Yes, I can see now that they mistreated you. Anyone would be angry.” Building an invisible foundation of trust. “With your aptitude,” she said, “it would be a shame to let your talents go to waste in a technical institute.”

By 1996 Russia’s armed forces were less than one-third they reached at the height of the Cold War. A semi-annual draft policy was complicated by evasions and desertion. Junior officers subjected to violent hazing and poor management. With a seemingly endless supply of negative press and infrastructural flaws laid bare by glasnost, there was no shame in considering alternatives. One day, Tovarisch Colonel called him into her office. On her desk was a dossier. “Read through this.”

Safin took a seat. He opened the dossier, staring down at the name in blocky Cyrillic. He did not say a word.

“Many years ago,” the Colonel said, “I knew your father. He worked for FSB, and his wife an informant.”

Safin blinked. He shook his head as if to clear it. “My father is dead.”

The Colonel nodded. “You were placed into the State's care but you were never alone. Your rescue from a life rotting away in internat at eleven. Your diagnosis of oligophrenia, imbued upon you as any orphan, was corrected at fourteen. This was no mistake.”

“He’s dead,” Safin said. Anger disguising the greater pain of possibility. “He's never contacted me in my life.”

“He could not risk exposing his identity,” said the Colonel tartly. “But that is beside the point.”

Safin stood up, putting distance between himself and the desk. “I did nothing to warrant this.”

The Colonel's eyes flashed. She did not stand from her chair, or raise her voice, despite the capability. “You have been treated unfairly for most of your life. This does not make you unique or exceptional. The State has nurtured you where your own family abandoned you. It is not easy to accept. But you must understand, the State has been generous enough to put you on this path, and it is only right you return that generosity. You will sit,” the Colonel said, “and you will listen.”

Safin walked back slowly. Took his seat. Staring at the dossier, he must never forget this face. He would steel his efforts to survive and prepare until the day they would meet. Radinovich would explain everything. Then he could die.

“Your assignment is a matter of utmost secrecy. You will follow my orders without question or delay.”

“Yes, Colonel.”

He took an early morning flight from Kazan to Antalya, touching down in Munich and continuing by train. With seventy-two hours to complete the assignment he was catching sleep in shifts. From Berlin Ostbahnhof to Attnang-Puchheim, he was confined to the window seat.

Shrugged awake, the bright blue sky leaving sunspots. He winced. “We’ll be arriving soon,” said the Colonel without looking at him. “Be ready.” With a shared eye colour and nationality, they passed for aunt and nephew.

Walking into Hotel Seevilla by midday, he noted the activity around the reception, the multicoloured brochures on display. No one struck up conversation besides the concierge, who described a few basic travel plans, then a dinner special at the restaurant on Wednesdays.

Safin paused. “Just looking. Thanks.”

He shoved his hands into his pockets. Back home he was just another student among hundreds. Out of country, he caught a lot of second glances but no overt questions. Just wait until they figured out he wasn’t here for the culinary event on Wednesday.

Attendant behind the desk motioned him over. He handed over his passport. Durmaz Vadim Radinovich, seventeen. Russian. Could pass for fifteen or his early twenties.

The phone on the wall rang. The attendant excused herself to engage in a brief, one-sided conversation, frowning at Safin's passport. When she hung up, her smile was a little stiff. She stole a glance down the antehall that Safin didn’t miss. She apologised for the delay, before placing the key into his palm. Rooms were up the staircase on his right.

Safin nodded. “Thank you.”

There was a small alcove between the restaurant and reception. Safin took up a spot by the bookcase. Alone, save for a man in a double-breasted suit and dotted blue tie. Probably in his early thirties. This man looked up at Safin, who nodded curtly. Then the man said, “Est-ce que vous skiez?”

Safin could read French from a newspaper headline, but his conversational skills were not as fluent. “Non.”

“Moi non plus. C’était un des passe-temps de mon père. Il était ce qu’on peut appeler un survivaliste. Il m’a inscrit, moi et mon jeune frère, à la Rote Teufel quand nous étions petits garçons. J’ai abandonné au bout d’un mois, je n’avais pas l’aptitude physique. Mon frère excellait. Il m’écrivait du Tyrol presque toutes les semaines. Mère était inquiète qu’il se fasse tuer, mais d’une manière ou d’une autre, il a toujours réussi à tromper la mort.”

During this diatribe the man walked over as if they were lifelong friends. Safin kept his expression neutral. Sooner or later the man would get tired of talking to a wall. It was unnecessary to stand so close.

“Puis un jour, il y a eu une avalanche à Kitzbühel. Mon frère est rentré mais pas mon père. J’ai toujours pensé que c’était un peu fortuit.” The man glanced at Safin. “Je suis désolé. Je ne voulais pas m’imposer.”

Safin, out of patience, said, “Ich bin nicht interessiert.”

The man paused. “Your German is quite good. Where did you learn?”

English as poised as his French. Safin followed suit. “School.”

“Ah, I see. You’re a transfer student?”

Safin looked down the hall at the passersby. No sign of the Colonel. “I’m waiting for my aunt.”

“That’s peculiar! I happen to be waiting for someone as well.”

Safin said nothing. The Austrian's mouth turned up at one corner. Offering his hand with a good-natured chuckle. “Where are my manners? Heinrich Stockmann.” They shook. Stockmann’s eyes and tone were diffident. “You must be Gostan's boy.”

Safin's hackles raised. Stockmann was watching him closely. He hadn’t told him he was a transfer student. Who the hell was this guy?

“Durmaz!”

Safin stood a little straighter.

“Hello, Rosa!” said Stockmann brightly. “I’ve just been talking to your charge. Nice young man.” He clapped Safin lightly on the shoulder; Safin glanced at him, irritated.

The Colonel did not smile. “Herr Stockmann.”

Stockmann took his hand away with a resigned smile. “I understand, you are busy.” He caught Safin’s eye and winked. “Best of luck with your studies.”

As Stockmann walked down the antehall down into the restaurant, the Colonel motioned to him. “Follow me.” Down the road, they discussed the route about Lake Altaussee. “Leave before sunrise. Take Puchen until you reach the cabin. When you’re done, don’t linger. There is a hill to the west. Climb until you reach the lot at Loser-Panoramastraße. The driver will take you to the train station. You should be back home in four days.”

Safin was looking back down the road. “How’s security?”

“We’ve taken care of that. The civilians shouldn’t ask questions.”

Returning to his room. Standard, sparsely furnished. He had a view across lake. Suitcase at the foot of the bed contained a CSA vz. 58 Carbine with a side-folding stock. In the closet—white parka, snow pants and black boots. Bulletproof vest to be worn over his shirt. In its own carved oak box, a porcelain mask.

Safin took the time to assemble and disassemble the rifle. Everything in working order. He glanced briefly at the mask, scowled. A woman’s face upturned in a smile. It wouldn’t protect him from the elements. Craftmanship he’d seen approximated in print. Then his attention caught on a small scrap of paper. Must have fallen out of the box. Safin bent down and picked it up.

Colour photograph of a man and woman. You could make out the golden chevrons on each shoulder of his suit and the sharp lines in his face. The woman was probably in her late twenties. Neither of them smiled. On the back of the photograph was the following message:

König forgets his dues. Adelheld sends her regards to Blanchard. Relay this message.

He puzzled over this for a while. Slept on it. Geared up and left before daybreak. Minutes down the road, his face was prickling. The parka was warmer than his own jacket.

No one else on the trail. The lake undisturbed, a frozen pane of glass. By the time he got to the cabin the sun was just creeping past the mountain range on the horizon. He walked up the front steps, rifle at the ready, knocked three times and stepped back.

Footsteps on the other side. The door opened and he saw nothing. Looking down at a girl, Safin hesitated.

The Colonel never said anything about a kid.

“Are you Blanshar?”

The girl responded in French. She went to close the door. He stopped her with his arm, one gloved hand resting on the jamb. She had to crane her neck to look him in the eyes. Woman’s voice called from inside, also in French.

“What did she say?” The girl said nothing. Her eyes shifting to the rifle slung around his shoulder. “Blanshar,” Safin insisted, switching from Russian to English, “Is here? You know her?”

The girl’s expression blank. Safin shouldered his way over the threshold and she made no attempt to stop him. Smell of stale tobacco came to him first. In front of him, a hall leading further into the house and a flight of wooden stairs.

He found the mark reclining on the sofa. Same face in the photograph, gaunt with age. Scent of stale bile and bleach. Her eyes flickered to him, nostrils flaring. “What the hell is this?”

Safin relayed the message.

She offered a few empty, condescending threats to his life. He studied the bottle on the table, the glass partway full. Her husband was not around often. At gunpoint, she didn’t cringe, beg for mercy on her daughter’s behalf. She didn’t ask why, just looked at him with a strange half-smile.

Two shots.

Through the curtained window on the wall behind them, miles of unbroken snow reflecting sunlight. The air now tinted by a fine red mist. Pooling blood edged the soles of his boots.

Turning to leave, the girl was still huddled against the wall, one hand shoved in her coat pocket.

She hadn’t seen his face. Why waste the bullet?

From her coat she drew a handgun; he instinctively reached for his rifle. Her first shot grazed his jaw below the ear, shattering the mask. Unloading the clip into his chest only staggered him. The firing stopped. Front door bashed against the wall.

She was running towards the lake. Operating on fear, not logic. If she died, so did his future career. Her smaller legs could not carry her fast enough. Safin stopped a foot from the bank, next to the dory. He barked, “Stoy!”

She looked back, and her footing slipped. With a short scream she tumbled, landing flat on her ass. Safin took a slow step onto the ice, then another. The ice creaked but did not give.

“Reste loin de moi!”

The girl levelled the gun at him, hands flushed from cold. Safin pushed the rifle behind him, spat a mouthful of blood and said, “Ich werde dich nicht verletzen.”

The girl’s aim faltered. “Du verstehst mich? Da war ein Fehler.” He approached until he could see the whites of her eyes, and offered his hand. “Ich gehe mit dir. Niemand wird dir weh tun.”

She was looking at his face, where his eyes should be under the painted mask. She lowered the gun. Rather than take his hand she crawled on her stomach towards the bank. Once she was back on solid ground she got to her feet, glanced over at him. “Du sollten nicht auf dem Eis stehen.”

“Warum hast du es dann gemacht?”

She gave him a look like he was being obtuse on purpose. “Warum kümmert dich das?”

Safin was only a foot or so from the bank. Ice beneath his boots giving way to crisp snow. The girl trailed behind.

“Pourquoi tu fais ça?” Safin ignored her. A white-hot pain throbbing in his jaw. Her bootsteps crunched faster to keep pace. “Mon père ne prendra pas à la légère une attaque contre sa famille. Une fois qu’il aura découvert ce qui s’est passé, il vous suivra. Vous feriez mieux d’avoir des amis qui vous protégeront si vous ne souhaitez pas que ce soit fini pour vous—”

“You know,” coming to a full stop, turning to address her, “for a girl who just lost her mother, you talk a lot of shit.”

The girl looked as if she’d been slapped. Safin continued toward the cabin. “You think I’m scared?” Her English pristine next to his. No doubt she’d gone to all the best schools. “Do you know who my father is?”

Easy to talk when your dad could pay off the whole town. The authorities would overlook the bullet holes in the walls and furniture, the foreign kid with a military rifle, the hotel within walking distance, and call it suicide.

Tiny shards of porcelain embedded into flesh. Blood pooling under his tongue, into the back of his throat. Pausing to spit—she averted her eyes—he said, “You should ask yourself who wants you dead. Then you can be angry.”

They came up to the front of the house. The girl was idling by the steps, staring at the front door, still clutching the handgun. Safin stood there in the cold, blood running down his jaw.

“Hey.” Turning with a flinch, terror resurfaced behind her wide, blue eyes. He paused. “It’s not personal.”

Shouldering the rifle, moving towards the trees, out of sight. Up the hill, where the unmarked black vehicle idling. The Colonel barely looked at him as he opened the door, took a seat. “Who injured you?”

“I was taken by surprise. It’s no matter.”

She slowed around a turn. “I trust you took care of it.”

“I was instructed to shoot the woman.” His jaw grit through the throbbing pain in his jaw and sternum. “Not her child.”

“Were you seen?”

Safin paused. “No.”

The Colonel’s eyes were difficult to read. “Then, there is no trouble. Leave the rifle and the mask here. You have time to fix your face.”

⁂

Along with other of the military aristocracy, Safin was not subject to the fierce competition between officers to place in military academy. After seven years training, he never had to see a day of service in-the-field. An executive agent at twenty five.

For his last mission he took a ferry to Severo-Kurilsk, debriefing on the way. The target was a former senior officer in the FSB’s Criminalistics Institute. Specialising in poisons, he went on to found his own pharmaceutical institute. Before the dissolution of the USSR, this officer planned to shift from state-sponsored biological weapon programs to government-funded research. He had not been seen since the 1980s. Intelligence suggested he was running a facility out of the Kuril Islands under a different name.

Tracking down the target in a small, unassuming house several miles away from Severo-Kurilsk. Coniferous trees across the horizon. A bitter winter dissolved into spring. Nothing else besides an old wood shed, full of industrial canisters of herbicide that hadn’t been in-use for decades. The scratches on the floor and disturbance of dust would suggest it had been recently vacated of other belongings.

Safin checked the house. The front door was ajar. There were signs of recent activity in the kitchen. A kettle off the burner full of stale water. The radio was on.

He walked into the living area. There was a man seated at the table, slumped on his arms. “Radinovich?”

No response. Safin came close enough to notice the blood pooling from the back of his head, starting to coagulate. The silenced Makarov pistol behind the chair.

Safin had no time to allow his emotions to catch up. He checked the bookcase—various books on plants, historical books, all USSR-era. An unassuming life in exile. Self-sufficient.

The bedroom, spare. No pictures or furnishings apart from a trunk, not unlike the tumbochka at the foot of Safin's childhood bed, only larger. Documents. A photograph of a man and woman, two boys and a girl. The woman’s eyes matched his own. The man, about as tall as him now. Strong posture that had declined slightly with age.

Safin continued reading through reports, newspaper clippings. Shortly after giving birth to a third son, the officer disappeared. His wife was detained. Under interrogation, she confessed that this officer planned to defect from Russia with his family. In return for her loyalty, the government promised immunity. A few months later the wife, two sons and daughter were found deceased in their own home in Kazan. Max Zorin, a doctor and close friend of the Safin family, claimed food poisoning. The child was taken into the care of the state.

Yet there were letters of correspondence between Gostan and various military officials. The maternity ward and baby house, the correctional school. Safin’s hands shook so badly he almost dropped the papers. Twenty six years spent preparing to demand an answer. He had no defense against this.

The door to the bedroom moved wider. Pistol nudged the back of his head. “Stand up.”

Safin was marched outside back into the cold. Two men in FSB uniform stood by the shed. The butt of the pistol struck Safin's head, compelling him to kneel. The can of herbicide lay waiting.

⁂

The first night in the Zurich safehouse, he woke to a tingling in his feet. Moonlight limned through curtains. He’d always been a light sleeper. Ever since his military discharge, he had to be mindful. Always kept a fresh pair of socks close at hand. Well-fit shoes by the bedside. He could not walk barefoot without crippling sensitivity.

He could lie awake for an hour or several but the result was the same. He listened to her pace advancing, receding, across the length of the opulent bedroom. Then he did what he was apt to do when he couldn't sleep.

The kettle was clean on the outside. White mineral deposits around the lid, on the bottom and inside of the pot, denoting use of tap water. Unsurprising, but easily remedied. Check cabinets for distilled vinegar and baking soda. Combine one part water with one part distilled vinegar. Denomination will vary depending on the size of the kettle. Boil this mixture in your pot for five to ten minutes, allow it to cool and then pour the mixture out. Combine 60 mL baking soda with a full pot of fresh warm water and allow the mixture to sit. After ten minutes, pour out the baking soda and water mixture, rinse and allow the pot to dry completely before replacing the lid.

All of this to be undone by the successive tenant, but Safin did not mind. This habit as emotionless and automatic to him as assembling a rifle. He did not drink out of anything without inspecting it first.

It had been an undemanding week, putting together the itinerary, handling White's daughter. Not the pompous spawn of a bureaucrat he'd come to expect. She didn't test the limits of her confinement, or ask too many questions. No damning proclivities. Her presence in SPECTRE's affairs bordered on inconsequential.

The incident in Conakry necessitated direct intervention—everything else could be accomplished by proxy. Blofeld insisted that White’s daughter was a special case, requiring the attention of someone more familiar. So each night, he was compelled to relive her death of innocence. The grief stuck in her throat. Her hiccupy breaths easing into shuddering acceptance. Contritions in muffled French.

Tonight the safehouse was quiet. He circled back from Madeleine’s room to the kitchen. Digital clock on the microwave oven read 05:58. Primo stood at a distance, eying the kettle on the counter. “You’re offering her tea?”

The brew was cold. Safin had neglected to drink any himself. “She had a rough night. It won’t get easier in Norway.” Setting the box of ammo on the counter, Safin eliminated all traces. Emptying the cold tea into the sink, he rinsed them individually before turning off the water.

“What’s this?” Primo was holding the box of Speer JHP.

“From her luggage.”

Primo set it down. “You don't trust her?”

“I shot her mother when she was a child. I don’t expect forgiveness.” Safin turned off the water. “What she does with the information is of no interest to me.”

Primo’s silence spoke for him.

A little while later, the lighter footsteps came down the hall. Madeleine, bundled in a dark coat that stifled her finer features, had already handed off her suitcase to Primo. They were alone in the room. Without looking at Safin directly, she said, “I understand you cannot tell me very much about what I’m walking into. But without my father for consul, all I have is you. What can you tell me about this position in Norway?”

“You will be operating out of a private clinic. That's all I know.”

Her mouth drew thin. She put her hands into her pockets, but avoided looking at him. “I’ve never taken a life. I used to think only monsters could separate their emotion from intention.” She’d noticed the ammo on the counter. She swallowed dryly. “To enact my own perception of vengeance, I’d go against what I stand for as a doctor.”

“Why keep the gun?”

“Because I’m not naïve.” Her eyes flitted over at Safin. “How long did you know who I was?”

“Since Conakry.”

“And what did you think then?”

He turned to look at her directly. The ten year-old clutching her father's gun. The twenty-eight year-old, too exhausted to weep, would still pry him apart at the ribs for even a hint of closure.

“Nothing.”

Transitioning away from the impassive mountain range to the station in Genève. The sky turning steadily to halcyon. Madeleine did not sleep on the way to the airport. Her attention kept flitting around, habitual. Hands in her pockets tensed into fists, or on her knees. On the train, tilting her head in the direction of the window, she did not rest against it. Sunlight on her face brought out the emotion trapped behind her eyes.

A life fraught with survivor’s guilt. Besides the truth, the next mercy he could offer was euthanasia. She asked for nothing on the plane as he took the aisle seat beside her.

Soon enough he'd be back to his assignment. The chemical attacks in West Africa had nothing to do with SPECTRE. The current theory from SPECTRE’s intelligence suggested a prototype bio-weapon the current SIS wanted to keep under-wraps. Still a convenient excuse for SPECTRE to implement itself without definite alliances, offering counterfeit pharmaceuticals for a disease without cure.

The WHO was doing everything possible to convince the rest of the world that this situation was under control. Due to safety concerns, the harbour had to be be shut down. Most of the patients that passed through MSF’s hands were mineworkers or participated in mining infrastructure. Since the breakout did not originate in Conakry, and whatever the MSF had been injecting the afflicted with was ultimately deemed ineffective, the news couldn't detract forever. Various members of the MSF team were coming forward about their experiences.

The workers and their families promised compensation. Little could be done without the issue of government and military intervention. Public interest wasn’t going to affect much on its own. The insurgents had outlived their purpose. Now they would be crushed against the government's forces without need for a third party to meddle. Whatever funds were scrounged up and donated could be rerouted in the interest of SPECTRE reclaiming the mines inside of a year.

There were no true allies in this business. Only different means of righting the same wrong.

Madeleine's head draped onto his shoulder, breathing evenly. Safin did not turn to look. She had suffered enough.

Her lodgings had been settled beforehand with the forenom running the aparthotel complex. A small but ostentatious flat close to the city. A half-hour away from where she would work. Madeleine walked around the room, did not sit down or touch anything. Safin remained on the threshold. “If there is a problem,” he said, “the man to speak with is Kęstutis.”

“I don’t suppose this person will also tear apart the room?”

“It shouldn’t come to that.” He paused. “Where is your mother buried?”

Her eyes snapped to him. As if he would claim it was a sick joke at her expense. A test of her emotional fortitude. But he let the silence build until at last she said, “Döbling Cemetery, in Vienna.”

Safin nodded. “My father’s ashes were scattered over Okhotsk. We weren’t close.” She returned his silence in lieu of her condolences. He said, “Good luck, Dr. Swann.”

No lingering sentimentality. He simply turned and left.

⁂

Three months after the Oslo operation he paid a visit to Vienna. During the meetings at the Palladio Cadenza in Rome, each time he looked Mr. White in the eye he saw the girl’s face. The wife, unmourned.

Once an ambitious teenager, creating his own language of coded messages in bouquets, which his fellow suvorovtsy called “thoughtful,” first, then “sure, just like a serial killer” when pressed for acceptance. After brooding over his notes he kept running into complications. Cultural disparities between symbolism and colour. Maintenance costs. A level of ingenuity lost on those who attended the funeral, and saw only hydrangeas.

At thirty four, he deliberated for a while in the florist before settling on an even-numbered bouquet of white roses — devotion, silence, reverence for the dead.

Drab, civilian clothes. Heavy coat, gloves, balaclava. The elements no longer an inconvenience but a reminder of what he once took for granted. Civilians caught a glimpse of the pitted skin around his eyes, his ragged voice. The trembling in his hands subdued into control.

He stopped in at the help desk and asked for the name Blanchard. According to the staff there was no record of anyone with that last name. He asked to look at the records and was told they could not give out this information. Perhaps someone else had taken the spot. After the lease ran out on the grave, the person could have given up the right to an individual headstone. Erased from existence, just as Vadim Durmaz.

Safin apologised for the misunderstanding. He walked outside, flushed from cold.

“Come to pay your respects?” Mr. White stood a few feet away by an unremarkable headstone. Safin said nothing. White gestured to the bouquet. “That’s a handsome arrangement. A friend of yours?”

“There was a mistake,” said Safin.

Mr. White stopped. All of a sudden, his eyes were sharper, his tone less friendly. “How did you find this place?”

“I asked where she was buried,” Safin said hoarsely.

White studied him carefully while keeping his tone light, “I haven’t been here in fifteen years. My daughter was more sentimental, if you can fathom it. Used to order flowers while she was going to university.” He offered Safin a tense smile. “She stopped sending them after the lease ran out.”

Safin said nothing.

“You know, she’s doing well for herself. I was in Norway for her birthday, and she invited me for lunch. She’s always been proud—but she started talking about her mother. Told me she’s figured out what happened.” White’s voice hardened. “It’s not complex. The marriage was failing, so I did what was necessary to keep my family safe. It doesn’t matter how high up you are. Sooner or later, every man has got to to cut his losses. But, she’s always had difficulty understanding this.”

“She cries out in her sleep,” said Safin, “but she never tells you why, does she?”

White went very still. The next moment, disarming Safin of the bouquet and striking him on the head in a manner more insulting than harmful. “You son of a bitch!” White thrust it at his feet and grabbed Safin by the collar. Safin, taking air into his lungs, wheezing on the exhale, did not flinch. “You’ve got some goddamn nerve, coming here after what you did,” said White through gritted teeth, “so the least you can do is explain yourself.”

“To pay respects,” Safin rasped. “And because one of your friends killed my family. The Cipher. Was it incidental? Or intentional?”

White’s expression shifted from icy rage into controlled indifference. He released Safin, and adjusted his hat. Turned away, as if to compose himself.

“Back in the eighties,” said White, “I used to deal with a man named Gostan Safin. He worked in the FSB’s Criminalistics Department. Got into some disagreement with his client, so they picked off the rest of his family just as we cut him a deal to get out of Russia.” White paused. “The last I heard of him was at his funeral in 2004.” His expression hardened. “You’ve got the same eye for poisons. But I had nothing to do with your family’s death.”

Petals scattering into the snow and stuck to Safin’s jacket. White said, “We may work for the same man, Lucifer, but he doesn’t forgive these aberrations.” His voice was flat, calm. A level of compartmentalization mastered over a lifetime. “I’ve surrendered my company to petty criminals who think that trafficking women and children is the future. I can live without my daughter’s forgiveness. But I cannot protect her.”

“What are you proposing?”

Under the gloomy light, White’s age became stark. His eyes lowered to the flowers in the snow as he said, “See to it she doesn’t suffer the same fate as her mother.”

Wow, that was a lot of work. So, let's break it down!

Safin's fake passport (surname, first name, patronymic) and his conversations with the Colonel correspond to Russian form of address. To my understanding, he might refer to her in private/among peers by surname, and in conversation either by first name and patronymic, or military address. Subordinates address superiors using only tovarisch and rank: ‘tovarisch Senior Lieutenant,’ ‘tovarisch Colonel’. Higher-ups address subordinates by military rank and surname, and Klebb is referred to as Comrade Colonel in the novel From Russia With Love.

Several of the Russian terms were adopted from this joint report from Human Rights Watch on Russian orphanages. Also some further reading on the military school in Kazan.

A big thank-you to Anja_Petterson and sesyeuxocean for additional input/corrections with German and French translations respectively, re: the hotel lobby & confrontation on the ice.

Information on Safin’s rifle was taken from this very helpful article. In Madeleine’s case, I looked into the different models of the Beretta manufactured during the 1990s.

Lines from the flashback in chronological order:

“Est-ce que vous skiez?” Do you ski?

“Non.” No.

“Moi non plus. C’était un des passe-temps de mon père. Il était ce qu’on peut appeler un survivaliste. Il m’a inscrit, moi et mon jeune frère, à la Rote Teufel quand nous étions petits garçons. J’ai abandonné au bout d’un mois, je n’avais pas l’aptitude physique. Mon frère excellait. Il m’écrivait du Tyrol presque toutes les semaines. Mère était inquiète qu’il se fasse tuer, mais d’une manière ou d’une autre, il a toujours réussi à tromper la mort.”

Neither do I. It was my father’s hobby. He was what you would call a survivalist. He enrolled me and my younger brother into the Rote Teufel when we were boys. I dropped out after a month, I didn’t have the physical aptitude. My brother excelled. He would write to me from Tirol every week or so. Mother used to worry he would get himself killed, but somehow he always managed to cheat death.

“Puis un jour, il y a eu une avalanche à Kitzbühel. Mon frère est rentré mais pas mon père. J’ai toujours pensé que c’était un peu fortuit.”

Then one day, there was an avalanche in Kitzbühel. My brother came home but my father did not. I always thought it was a little serendipitous.

“Je suis désolé. Je ne voulais pas m’imposer.” I’m sorry. I didn’t mean to impose myself.

“Ich bin nicht interessiert.” I'm not interested.

“Ty govorish' po-nemetski, kak shkol'nik.” You speak German like a schoolboy.

“Ernst, fils de pute—” Ernst, you son of a bitch—

“Stoy!” Stop!

“Reste loin de moi!” Stay away from me!

“Ich werde dich nicht verletzen.” I won’t hurt you.

“Du verstehst mich? Da war ein Fehler.” You understand me? There was a mistake.

“Ich gehe mit dir. Niemand wird dir weh tun.” I go with you. Nobody will hurt you.

“Du sollten nicht auf dem Eis stehen.” You shouldn’t be standing on the ice.

“Warum hast du es dann gemacht?” Then why did you do it?

“Warum kümmert dich das?” Why do you care?

“Pourquoi tu fais ça?” Why are you doing this?

“Mon père ne prendra pas à la légère une attaque contre sa famille. Une fois qu’il aura découvert ce qui s’est passé, il vous suivra. Vous feriez mieux d’avoir des amis qui vous protégeront si vous ne souhaitez pas que ce soit fini pour vous.”

My father will not take an attack on his family lightly. Once he finds out what happened, he will follow you. You better have friends who will protect you if you don’t want this to be over for you.

#fanfiction#madeleine swann#lyutsifer safin#mr white#canon divergent au#multichapter#colonel klebb#le chiffre#silva#ernst stavro blofeld#fanfic#sorry this was so late!

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hello friends ❤ With the new year ringing in I can’t help but look back on the abyss that was 2021 and focus on the bright moments in between: the people who helped make it better in great and small ways. This past year these blogs I’m about to mention have brought me joy, whether it be in the form of their support of my creations, sharing their owns works and creativity to admire and inspire, or just by being a friend—I felt compelled to shout out some of you who have been a delight to follow, be mutuals with, or see pop up in my activity. Thank you for being you. I hope your 2022 is filled with goodness and peace, growth and wholeness, and ultimately turns out to be a bright chapter. Here’s to new fictional characters and stories to fill the void 🥂🎆

a-c: @actuallyhansolo // @albertmasonry // @ammihan // @theashenphoenix // @assaultron // @azurejewel // // @bonniemacfarlane // @boozerman // @cavalieredispade // @cclkestis // @crownkillers //

d-g: @dicax-asina // @fashionablyfyrdraaca // @fettboba // @foundynnel // @thegunslingerstragedy // @gwynsblade //

h-l: @halfwayriight // @haloinfinite // @the-halo-of-my-memory // @heavensnight // @hoovesmadeofsteel // @hoseas-angry-ghost // @in-darker-dreams // @itspapillonnoir // @isaviel // @lilacandwhiskey // @liquidsnvke //

m-p: @mary-marion // @mistress-light // @miyku // @mr-morgan // @neketakas // @pagonyban // @porkchop-ao3 // @prairiemule // @preciousgyro //

q-s: @raccoonscity // @river-the-fox // @rivetingrosie4 // @rxkuyo // @shadows-echoes // @a-shakespearean-in-paris // @shallow-gravy // @shandrias // @sillygamingartghost // @silverstar15 // @snowthroat // @soazzar // @sternbagel

t-z: @tatzelwyrm // @tiredcowpoke // @ugh-my-back // @uncharted2007 // @vault21 // @vindicia // @winterswake // @thewolfkissed //

And last but not least thank YOU to my followers, you all make me feel liked and welcome here and I’m so so happy to share things with you 💕💕💕 Please know that I am grateful for each and every one of you who isn’t a bot 🌹

#some of you are really sweet and i'm naming names 😤♥#also i am so so sorry if i forgot anyone or you felt left out of this! it was not intentional my brain is just small#follow forever#typography is not my strong suit

77 notes

·

View notes

Text

I wanna thank @mrskrazy @theonlylolland @cavalieredispade @chrisfroot @minilev and @pebster for making my dreams come true! I have such a beautiful collection thanks to you lovely talented people! ❤

199 notes

·

View notes

Text

RDR2 Blog Recommendations

So to “celebrate” me hitting 500 followers I want to make sure other blogs get some recognition and love too! Please feel free to add on more blogs (and even your own) if I forget anyone! ^_^

Red Dead Writers

These are some of my favorite writers in the fandom. Some of these blogs are good friends of mine (and they’re all SUPER talented) and I hope you give them a follow ^_^

@have-some-gotdamn-faith

@unsarable

@somethinwickedthiswayrides

@javiersbluejacket

@crimsonredemption

@mrsescuella

@i-love-charles

@redemptionbaby

@whirlybirbs

@shyeehaw

@ladyboltontoyou

@morgan-macguire

@hello-imasalesman

Red Dead Artists

These are some of my favorite artists in the fandom. (Some make art for other fandoms as well, not just Red Dead.) There’s so much cute and beautiful works of art they’ve all made.

@mrskrazy

@hackeraxe

@mephistia-arts

@ppitte

@jaegervega

@rebelflet

@the-strawberryfarmer

@cavalieredispade

@frog-prince-kieran

@yeterah

Red Dead Role-players

These are either people who RP on their blog or that their blog is like an “ask-character” blog where they RP as the character getting asks.

@aint-no-odriscoll (I personally LOVE this one just because it’s Kieran and it really funny sometimes. Great job, you~)

@ask-charles-smith

@ask-albert-mason

@arthur-morgans-blogg

Red Dead... Misc.

These are ones where they either do art and writing or just really good posts... or I just don’t know what category to put them in and wanted them to be on this post.

@heart-of-gold-outlaw (Writing lil Modern!Reader things that I’m not sure what to call them but their funny and GREAT.)

@animekath (Does both art and writing)

@porkchop-ao3 (Also does art and writing)

@cowboy-canoodler (Used to write, go read everything they’ve written because it’s all great)

@your-fandom-aint-shit (Good rdr meme posts)

@pink-skye713 (great posts, and i think they still do art as well)

@kierthur (Great posts not all rdr)

@confused-rat (also great posts not all rdr)

@sebthur (Great posts not all rdr)

I know I’ve probably forgotten A TON of people and I’m sorry. If I forgot someone you love please add them in a reblog/reply so others can find them as well.

Thank you all so much! I hope you find a new blog from this and give them a follow!

(Please don’t feel bad if I’ve forgotten you, it’s not you, it’s my horrible memory of urls.)

#RedDeadRevival#Add more if I forgot anyone#Blog Recommendations#rdr2#red dead redemption 2#red dead fandom#red dead art blogs#red dead writing blogs#red dead rp blogs#red dead roleplay blogs#red dead blogs#Thank you all again

153 notes

·

View notes

Text

OTP Playlist

Tagged by @jacobsknifeplay

Since it doesn’t specify a fandom I did both of my OTPs from FC5 and RDR2 :D Although I hadn’t really thought of this for Elena and Javier yet 😅

Deputy Dabria Waters x John Seed

1. Revelator Eyes - The Paper Kites

2. Kill Our Way to Heaven - Michl

3. Gasoline - Halsey

4. Island - Svrcina

5. Die Trying - Michl

Elena de Rivera x Javier Escuella

1. Te Metiste - Ana Bárbara

2. Enamorados - Tercer Cielo

3. Te Voy a Mostrar - Diana Reyes

4. El Amor Manda - María José

5. Amor Prohibido - Selena

Ah it’s so difficult to choose only 5 songs >.< Art is from @myworldisbiworld and @cavalieredispade respectively 💕💕💕

Tagging @its-the-deputy @fkingpeggies @johnathot-seed @johnsrevelation @starsandskies @fluttyseed @shellibisshe @zacklover24 @harmonyowl @wolfnotadevil and anyone else who wants to do this. Sorry if you guys have already been tagged. Don’t have to do this if you don’t want XP

#john x dabria#javier x elena#fc5#fc5 oc#rdr2#rdr2 oc#far cry 5#red dead redemption 2#john seed#javier escuella#maybe one day I’ll add in Kaira and Julian to these things lol

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

'V is for Venice'

Ezio from Assassin's Creed II

#digital art#illustration#assassin's creed#ezio auditore#assassin's creed alphabet#artists on tumblr#tumblr art#cavalieredispade#cavalieredispade art

678 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Knight and Lady by CavalierediSpade

#knight#lady#court clothing#plate armour#longsword#chivalry#((Considering how fashionable the lady is...))#((and how unfashionable the knight is....)#((This is legit just Beguiler and I.))

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

Insult to Injury: The Director’s Cut — Chapter 03 [Revised]

This chapter contains commissioned artwork by the one and only @cavalieredispade. Thanks a million!

III: I WOULD NOT COMPLAIN OF MY WOUNDED HEART

Each December, on their wedding anniversary, Madeleine’s parents flew out to Tangier and booked the same honeymoon suite in L’Americain. Madeleine’s earliest memory of her mother was in that room; sitting by the open window to read, or have a cigarette, while Madeleine wandered around the room finding ways to entertain herself.

The rest of the year, she spent growing up in a two-storey cabin on the shore of Lake Altaussee, enshrouded by trees and limestone mountains. Her father’s occupation kept him abroad for lengthy stretches of time. Her mother stayed home a lot. She had blonde hair that was brittle to touch. Get too close and she smelled like smoke beneath her favourite perfume. Her arms and legs were always bruised because she had trouble getting out of bed, out of chairs, without falling or bumping into furniture. Madeleine could not remember seeing her eat much. Just taking naps throughout the day to stave off headaches. The only thing that ever seemed to put her at ease was her medicine, which Madeleine couldn’t administer in front of the maid, or her father.

Madeleine tried it only once. She spat it back into the glass with a poorly-disguised grimace. While her mother chuckled, Madeleine had to get up and fill a new glass for her mother. She heard her coughing on the way back, wet, congealed with mucous. Madeleine set the fresh glass down and waited for her to stop.

It tastes gross.

Her mother smiled. “It tastes bad because it’s medicine. You shouldn’t be drinking it, since you are healthy. Once you get to be my age, you will understand why.”

Her mother coughed a lot because she didn’t like to open the windows. She said it was just to prevent the cold air from getting in in, or hot air getting out. Besides, if Madeleine were uncomfortable she could always go outside.

Madeleine said, why do you drink it?

“Because I’m sick right now. Why don’t you go upstairs and play?”

By then, Madeleine was old enough to decipher the surgeon’s warning on the back of the bottle. Just like the gun under the cabinet, the magazine with five rounds past the legal capcity, her father’s choice in colleagues, her mother’s sickness, there were things you did and didn’t talk about.

As her mother began drinking more heavily, Madeleine would go to school or into the village with the bodyguard of the week. It must be lonely for her, sitting at home all day. Madeleine would spend some time with her mother if she was awake, just talking about the day, and her mother would sit and nod along as if she were still dreaming.

Sometimes she would drink too much and make herself sick. The maid showed Madeleine how to get stains out of the upholstery by diluting white vinegar or hydrogen peroxide with equal parts tap water. Not to combine vinegar and peroxide, creating peracetic acid which was an irritant. Cornstarch or baking soda to deodorize.

“If you want to do it properly, she said, mix ten ounces of three percent hydrogen peroxide, three tablespoons of baking soda, and two drops of dish-washing detergent. Mix until the baking soda is dissolved.

“Pre-test the upholstery by applying the cleaner in an inconspicuous place. Allow it to dry. If the fabric does not change color, spray the stain and allow the cleaner to work for an hour. If the stain is not gone, repeat the process.

“Rinse the cleaning solution from the area by dabbing with a damp cloth and blotting with a dry towel. Over time, detergent residue will attract dirt. The hydrogen peroxide could bleach the upholstery and weaken the fibers of the fabric. Then, you have to call a professional cleaner.”

Then, one day, the maid’s services were no longer required. There was no warning. Her mother said something about some of her jewelery missing, how you couldn't trust a lot of people. Madeleine nodded along. She was a very good listener.

The year Madeleine turned ten, a week away from her parent’s anniversary, she was home for Christmas break. She woke up a little earlier than usual because she was still accustomed to her regular schedule. She had a couple hours before she walked into town. She got dressed and came downstairs to fix herself breakfast. Her mother was sitting upright on the couch, in the same position as last night. Sometimes she fell asleep like that. Passing by, the acridly sweet smell of vomit permeated the air. She’d have to clean that up first.

In between the living room and kitchen Madeleine stepped on something small and crunchy. Her mother’s painkillers were scattered across the wood floor. She walked over to check on her mother, who was staring out the window without seeing. She didn’t respond when Madeleine touched her shoulder. Then shook her lightly. Called her name twice.

She noticed the half-empty glass, the upturned bottle of medication on the table. Her mother’s breathing, laboured. The bodyguard came in the house which her parents would never permit. He told Madeleine to get her things.

Madeleine’s father came home early in the morning. He explained that her mother took enough sedatives to make herself very sick, but nothing more. One of his most trusted associates, Dr. Vogel, would come here to make sure she was stabilised. In the meantime, he invited Madeleine alone to Morocco. To see more of the world, as he put it. Her mother needed time to recover.

Two days later in the lobby of L’Americain her father was chatting with the attendant behind the desk. He mentioned his wife (sick, again, poor thing) and daughter (just turned ten last year), a bit more delicate in their sensibilities. Her father led her upstairs to their room.

Madeleine set her own luggage down in a shady corner. The fine-cut curtains didn’t do much to stop the sunlight beaming in, the dry air. Madeleine went to the bathroom and checked her face. The white sleeveless cardigan looked elegant, but come evening she would have pink patches on the crown of her head, bare arms, tip of her nose. In a few days they’d start peeling. Madeleine made sure her hands were clean before tending to her face, which was still smarting. She took her time patting dry with the towel. She came back and her father was looking at the empty wall opposite the master bed.

“She never really liked coming here,” he said. “She just wanted an excuse to drink.”

Why did she make herself sick?

“She’s angry with me. Well, I haven’t been home as often as I should. There’s only so much I can do, now that she has gotten so ill.”

Does she hate me?

Her father stopped. The lines in his face accentuated by his frown. “She’s in a lot of pain. When people get very upset, they tend to say things they don’t mean. However she chooses to deal with that pain is her decision, but it is not your fault. Don’t let her convince you otherwise.”

Madeleine nodded. Her father’s hand smoothed her hair back; she stepped away, resisting the temptation to massage her sunburnt scalp.

He said, “You’ll have to change before dinner.”

Madeleine, biting the inside of her cheek, said, I know, dad. Frowning, she said, I don’t have to talk to Mr. Le Chiffre at dinner, do I?

“He is my business partner. You keep your opinions to yourself.”

Yes, dad.

Her father looked at her a long moment, then shook his head. “Here, you can’t go anywhere with a burnt face.” He motioned her over to the bathroom and started opening drawers, retrieving a tube of antimicrobial ointment next to the shaving cream. “There’s a hand-mirror as well, if you miss a spot. Just put it back when you’re finished.”

Okay. Thank you.

He smiled. Madeleine smiled back, even though her face hurt.

⁂

On the drive to the Paris-Est, Madeleine’s feelings dissipated into grudging acceptance of her situation. An independent contractor looking for ransom would not understand the significance of the name SPECTRE, nor refer to her father by his title of The Pale King. Neither Safin nor his associate bore the metal ring she associated with the black emblem on her father’s letters—from work, he would always preface to her mother’s scowl—or the scant, unnamed ones that began showing up at Aunt Droit’s house the summer she turned eighteen.

She looked at the back of Safin’s head and said, “You work for my father?”

“I was contracted.”

Madeleine scowled at nothing in particular. “I didn’t know he still hired men like you.”

“He does not usually employ those outside of his circle.”

Exiting the car, boarding the train, she already had her tickets in first-class. Safin took a seat adjacent to her, with the end of the car in his line of sight. His associate was out of sight, on the other end.

En-route, they’d go from Paris-Est to Strasbourg, then Basel, then arrive in Zürich; a four-hour commute, assuming no complications. She could sit and refuse to talk like an insolent child, or she could take a moment to dissect her only source of information.

Objectively, she placed him somewhere in his early-to-mid-thirties. Average height. Not as physically imposing as his colleague, but still in excellent shape. He had a soft face which made him look younger, despite the scarring. The backs of his hands were damaged to a lesser extent than his face and throat. A subtle tension persisted around the shoulders—back in her residency years, she’d observed the same tendency in men who came from prisons.

The attendant walked over smelling like artificial vanilla, and enquired if they would need anything. A rush of saliva flooded Madeleine’s mouth as before vomiting. She shook her head.

“Everything’s fine, thank you,” said Safin.

The attendant continued down the aisle. Madeleine exhaled. Sunlight beamed on the side of her head, warming her past the point of languid ease. All she had was the handbag at her feet; burner phone, wallet, spare cosmetics, and a custom holster for a gun she hadn’t touched since purchasing, years ago. Still in the safe, if it hadn’t been confiscated by forensics or whomever broke into her apartment.

Madeleine relaxed her shoulders. Itching to get out of her head and into someone else’s for a change, she said, “I never collected my luggage from the airport, you know. I don’t have much on me.”

“Your personal affairs have been accounted for.”

A well-dressed thug was still a thug. Now she was stuck with him for the rest of the commute. Madeleine couldn’t stand to sit.

“Where do you think you’re going?” asked Safin without looking up.

“Dining car. I haven’t eaten since this morning.”

Safin made eye-contact with the associate by the door and gave a slight nod; Primo got up and followed her down two car lengths. Madeleine took a seat at one of the tables. Primo was by the door again. He didn't order anything. The other passengers, the server, became non-entities. Ordinary civilians. Two strangers on a commute. She shouldn't stare diffidently around as if waiting for the other shoe to drop. Focus on having a quiet meal. She paid in cash. Tipped ten percent.

When she returned to her seat, Safin said, “Trouble?”

“Of course not.”

Safin glanced down the end of the train. “Very good.”

From Basel to Zürich, they were on the upper level of the SBB train, seated at a booth. Safin was closest to the aisle and by extension, the exit. Madeleine, in a spot by the booth corner, was getting a little sick of this charade. He wasn't much for conversation, and the confines of her own head were starting to wear on her. He was allotting her space but less visibility, like putting blinders on a horse. If this situation were truly dangerous, they wouldn’t be travelling by train in the first place. Too many possibilities for interception.

The passing attendant didn’t address her beyond a glance and a small, terse smile. Probably just wanted to get to the end of the shift. Or maybe it was just her resting bitch face. She was simply run-down by the events of this morning. Operating on fumes. A dangerous way to live, even with someone else looking over your shoulder. Just like her father, sending a bodyguard-slash-operative in lieu of explanation.

“Dr. Swann,” said Safin, “is there a reason you keep looking over at the door?”

It was the first thing he’d said to her in a while. “I was just thinking. My father never mentioned any property in Zürich.”

“Not property. It’s a penthouse. You have a room set up already. I’ll stay out of your way.”

Madeleine nodded. Parsing over his sentence in her head a few more times. She looked up. “You have a reservation?”

“Only in the interest of your protection.”

Madeleine stared at him. Scoffed. “This is ridiculous. I haven't had a problem in years. He still treats me as if I am indebted.”

“You took his money.”

Madeleine stared at him in disbelief. “I took it to get through university, which I could never have afforded on my own. I never asked for anything beyond what he deigned to offer.”

Safin’s mouth thinned.

“Now you don’t want to talk? Fine. Since you obviously have nothing better to do than humour me, there is something I’ve been meaning to ask. What, exactly, were you planning to do if I walked away? I understand you have your method of operations, but really. The middle of a police station?” Safin said nothing. “I guess even men like you have to get your kicks. It's not every day you get to lead someone at gunpoint—”

“Are you finished?”

His indifferent tone didn't match the look on his face. Before she went to Oxford, she would have never talked to a close-protection officer this way. Madeleine averted her eyes. She could feel him studying her over the edge of the sunglasses. He turned his head in her direction, said, “You dislike guns.”

“I hate them.”

“May I ask why?”

“When I was a little girl, a man came to the house looking for my father. He found me instead. He got very angry when I wouldn’t tell him where my father had gone, so, I defended myself.” She shrugged her shoulders. “That’s why.”

⁂

After getting off at the station it was only a short drive into the Wollishofen district. The hotel entrance flanked by a pair of men in suits. One of them nodded to Safin before bidding them entry.

The penthouse was a step above the apartment in France. Hardwood floors. Everything polished. Individual climate control, central heating and IDD telephone. The kitchenware looked new. Her room was already set-up for her. A gilded dresser by the bed. Pillow-top mattress. The marble bathroom adjacent, complete with a hairdryer, dressing gowns and towels. Twin lamps flanked the bed. Engraved into the ivory base of each lamp was the shape of a dragon, twisted in upon itself.

Hardly her father’s style, or to her own tastes, for that matter. He probably picked this establishment because it was close to where he worked. Running business meetings over in Schwyz. He'd always been pragmatic when it came to his family and occupation.

The suitcase at the foot of the bed called her attention. Opening it, she found the clothes she’d left in Arnaud’s apartment. She parsed through the fabric. Some of these, she hadn’t worn in a season or two. Going out more often. Getting compliments at work, out-and-about, trying to smile.

At the bottom of the suitcase, she felt something heavy and cold underneath her folded dress shirt. The Glock 43 in her hands, complete with a spare box of ammunition. Manilla envelope containing old birth certificates and copies of all her current information, plus forged papers. Everything from the safe. A level of attentiveness hovering between convenience and invasion.

She went over to the set of glass doors leading out to the balcony, and drew the curtains shut. Unpacking the rest of her belongings, she couldn’t hope to blend in wearing anything she’d taken to Conakry. She was not strapped for cash, and still had plenty of money set aside in a Swiss account—for a day just like this one. The type of life insurance most people her age could never afford, and the ones below her tax bracket would kill for.

Despite occupying an apartment together, the death of Arnaud had the same emotional weight as a newspaper obituary. An hour at most for sympathetic grief, then annoyance for the persistence of that grief. All this time, carving out an altruistic identity through deeds. Spending the rest of her life making up for inherited sins. Living with people for the sake of social convenience.

Taking comfort every month her father failed to acknowledge her, in this façade of a charmed life. Holding onto that impossible dream until karma caught up. Leaving behind nothing of herself, beyond the lives she might touch along the way. Taking perverse pride in the impossibility of knowing an enigma. Each time, the quiet of each new office, the empty apartment, became a little more encompassing.

She was going to be here a week. She would have plenty of time to recuperate. And heaven forbid, enjoy herself for once. She was not going to sit here and cower like she was under house arrest.

Coming into the living area, she caught sight of Safin and his associate.

“The room is fine,” she began, “but, if I’m going to be here a week I’ll need some things in the morning.” Safin held her gaze in lieu of speech. “Just clothes. I don't want to walk around in things I wore a week ago.”

Surely, he would rebuke her. Call her out as a trust-fund. She had given him every right. He levelled with her and said,

“Once we work out an itinerary, that shouldn’t be an issue.”

⁂

That night she buried herself under the soft blankets. Dreamless sleep the most precious amenity of all. If she started taking pills she’d draw attention to herself. She dreamed she was back in her childhood bedroom when her mother called from downstairs. Madeleine checked the rooms and couldn’t find her mother anywhere. Someone she didn’t know, standing in the hall that led to the living room. She said,

Où est ma mère?

The man turned. He was dressed in a jet-black suit.

Laissez-moi passer. J’ai besoin de parler.

The man motioned to the living room with a lanky arm. "Elle vous attend."

With each step the hall increased a little further and further. Living room should only be ten steps away, not fifteen. Not twenty. When she looked back the man was elsewhere. The living room was empty. On the sofa was a large, red stain. Her mother must have spilt the wine.

The shock of cold liquid percolating her socks. Someone had tracked water into the house.

She followed the trail into the kitchen. A different man hunched over the sink, in a white coat and snowpants. A rifle slung around his shoulder, at his hip. Black gloves. Black boots still damp with melted snow.

Before she could say a word he grabbed the rifle and turned to aim at her with mechanical precision. Muscle memory.

"You aren’t supposed to be here." His accent wasn’t Austrian, or French. Garbled through the blood trickling into his mouth, under his tongue. "Get out, and I’ll forget about this."

There was a hole in his jaw the size of a 9×19mm Parabellum. Nine rounds loaded into her father’s Beretta 92S, under the cabinet with the bleach.

She explained in a high voice how the stain in the living room needed cleaning. Her mother would be very upset if she didn’t. She just needed to get to the cabinet for a moment, please.

His teeth bared, stained red. Finger on the trigger. "I won’t ask again."

She opened her mouth and screamed, maman, run—

Two shots. Impact tearing through her body without regard for gravity. Looking down in time to see blood spattered across the hardwood floor. Brain matter and bone fragments against a hot car window.

She plunged her hands into herself. Clawing away the sheets. Unbroken skin, sheened in sweat. Her eyes flooded with tears as she sat up and began to rock herself back to stability. Waiting for the initial swell of terror to pass, as it always did. Regulating her breathing. Just a trauma response. Sitting still, unsure if it was midnight or five in the morning.

Pressing her face into her palms. A dull throbbing behind her eyes, in the base of her skull. About to get up when she heard the footsteps. Movement from the hall towards the living room. A few seconds later, Safin’s voice, indistinct. She couldn’t make out what he was saying at first. Something in Russian. Orders from his employer, most likely.

And what must they think of her? Another privileged idiot, living in a bubble. Disrespectful to her father and his syndicate. Hypocritical.

She contemplated feigning sleep. The warmth of the sheets was too cloying. Her phone read 06:21. Still too early for her to be awake. She stood up, barefoot on hardwood, creeping over to the balcony. Reaching out to touch the pane. Cool glass kissing her naked palm. In two weeks it would be October. Two months from now, the ground would be laden with snow. The ocean grey and still.

Opening the door. Stepping out onto the balcony, gripping the rail. Taking fresh air into her lungs until the soles of her feet smarted. Hardly any boats. Just her and the horizon and the night sky.

Stumbling into the bathroom when she couldn't bear the cold any longer. Bags under her eyes more pronounced than the day before. Madeleine had a shower, trying to piece together the dream, hazier than in her youth. Visceral details heightened by recent exposure. An intimation of childhood memories depicted in abstract. She shook it off, dressing for the day. It was only a dream.

Before she left the room she caught the silvery glint in her peripherals. The old television reflecting the light from outside. Combing around the drawers for a remote. She clicked it on. Quickly hit the mute button. Squinting at the harsh colours that only reignited her headache. Flitting through channels for news. Poring over the headlines. Not a word about the MSF.

She sat there for a while letting the colours wash over the room. Clicked it off and went downstairs to have breakfast.

Safin, hovering by the glass doors in the living-room area overlooking the ocean front, was dressed as if for another commute. “Dr. Swann,” he greeted.

She rifled through the pantry and found it stocked. Looking for some cereal, something basic—catching briefly on the bottle of liquor. Madeleine took the cereal, fixed herself a bowl and some coffee. Still had a headache. Light breakfast. Plus, the caffeine would dehydrate her.

“I don’t suppose this safehouse has any painkillers?” Safin looked over. She was already going through cabinets. “It’s my head. Just the weather.” She met his gaze with more confidence than she could back up. Safin’s attention shifted to the side of her head.

“On your right.”

She took two with her coffee. Ate in silence. Waiting a week in the hope her father might have an excuse was a truly miserable proposition. What would she say? Hello, Papa. I’m still alive. Did you pick this location to remind me of your home in Austria?

Well, one thing at a time.

“Who do I speak to when I’m ready to leave?”

In lieu of a response, Safin glanced over at his associate.

⁂

She couldn’t travel beyond Zürich’s aptly-named canton. She could not contact anyone else outside of SFT to confer information about her father’s whereabouts, or anything else for that matter. Aside from that she was free to go wherever she liked within the constraints of the itinerary.

First, clothing. That took her to Bottega Veneta. In Flagranti’s Business Acumen playing over the intercom. Madeleine’s hackles raised. The painkillers in effect. Caffeine wearing off. She started parsing out signs. She hadn’t really thought about what she needed beyond the vague idea of change. Starting fresh. So accustomed to the life of a disconnected middle-class that its opposite became seductive. Perusing the aisles in a daze. Selecting whatever pulled at her heart in a perverse reminder of home. Nothing too extravagant. A new raincoat and a couple pairs of shoes. Navy scarf for the winter months. Spare lipstick. A few more shirts and dress pants in monochrome. Spare underwear, socks.

Spent an hour trying it all on. Avoiding the eyes of the woman in the glass. She didn’t feel any different. The raincoat was too dark. She might as well be attending a funeral. She already had a reputation for being severe. What did it matter? She was always severe and the rest of the world could just bite the bullet.

The associate was waiting, outside. Probably didn’t give a damn about her, either way. She wasn’t about to humanise him beyond his occupation. They made brief eye-contact. Unimportant banter between her and the cashier during the transaction. Associate was taking her bags. Walking with her over rain-slicked asphalt. Back into the car. The beat of raindrops on the window lulling her into a false sense of security.

Snapping herself out of it when the car stopped. Treading up the stairs, down the hall. Pulling old clothes out of drawers, off hangers. Substituting her purchased goods. It wasn’t enough to fill the wardrobe, but she would have time to buy new clothes. Set aside the old stuff to be dealt with.

Each time she returned to the safehouse, there were men checking over everything. Protocol, on top of all the scrutiny.

“I don’t want them in my room when I come in,” she told the associate. “Around the premises, and they can check the cars if it is necessary. If they must check all the rooms, fine, I just don’t want to see it.”

Childish to her own ears. Too beaten-down to think better of it. The associate just said, “Talk to Safin about it.” He walked out of the room without looking back.

That evening, Safin was lingering around the living room. He'd made himself tea on the stove. Without looking up he said, "I hear you are feeling crowded?"

Madeleine scowled. "He told you about that?"

"That's all right." He paused. "I'll accompany you."

The next few days were a tolerable blur. Wandering through Bahnhofstrasse. The Beyer Clock and Watch Museum. Next day, the Museum of Graphic Design for ten francs. Bellevue Square. Sattel-Hochstuckli. The three hundred seventy four metre Skywalk. Dinner at the Mostelberg-Stübli. Home again, each time without incident.

On the job, Safin hardly said more than a couple words to get his point across. But he gave her no reason to acknowledge him beyond this, dissolving into the background noise until he was needed. At least they weren't glowering at each other.

Apart from this, he was not around except for very early in the mornings. At the safehouse he would acknowledge her in passing with a curt nod.

How much normalcy could she put up with before she broke down? She had no more power or relevance than the common man and the only difference was her awareness of futility.

Inevitable, perhaps, that her thoughts would stray back to the MSF. Conducting research on her own, in the mornings and evenings; parsing through official news sites on her laptop, then underground articles, statistics, and anything else she could scrounge up.

The Guinean military had been busy quelling unrest for the last week, but there were few details. Several key figures in the MSF were currently under investigation, tarnishing the reputation of the organisation. That stuck around the headlines, right next to some lesser story in the corner about various pharmaceutical companies cooperating in tandem with the Red Cross and clean MSF figures to ensure there was no repeat affliction throughout the rest of Africa. Madeleine didn’t see her face or any mention of a Psychosocial Unit mentioned anywhere.

By day four, it was all she could think about. She alternated between laying in bed and taking down notes from various news sources. She slept one hour. Shambling downstairs on a very shameful autopilot. No real appetite. Safin nowhere to be seen. It took all the energy she had just to stand. Maybe she could take a free-day if she was polite. He had already accomodated her other, silly demands. Moving over to the sofa. Slumping into it. Closing her eyes. Only for a second.

Sharp staccato of rifle fire tearing apart a wooden door. Gun in the cabinet, next to the bleach. Heavy footsteps on wood. On carpet. She’d never get there in time.

A gloved hand on her shoulder. Jerking awake with a guttural hitch.

“Dr. Swann?”

Face-to-face with the last person she wanted to justify herself to. She recovered her composure, averted her eyes. “I—I’m sorry. It was just a nightmare.”

“About your mission?”

He was still holding her shoulder. He didn’t need to restrain her. She was perfectly aware of her surroundings. “No. I’m not sure what. Anyway, it was only a dream.”

“Don’t insult my intelligence.” His grip tightened, causing her to flinch. “If a client came to you exhibiting these symptoms, what would you assume?”

Madeleine held her tongue.

“This is not the first time you have exhibited this behaviour. Mental or physical distress to trauma-related cues," he inclined his head, "an increased fight-or-flight response. Difficulty sleeping.”

“So, you can define post-traumatic stress disorder. It does not make you my analyst.” She brushed him aside, staring at her hands balled up on her knees. “Most of the time, I don’t remember my dreams.”

“That’s a strange thing, to not remember something so distressing.” An undertone to his voice that made her stomach clench. “Tell me, did you buy your way into passing your psychological evaluations?”

“Let me make one thing very clear to you,” said Madeleine, standing up to look him in the eyes, “I can accept that you are here to keep me alive. I’ll go along with your precautions, or whatever you think is necessary. Your personal opinions do not apply. If that is more than you can handle, I’ll simply find someone else.”