#chadian cinema

Photo

SUBLIME CINEMA #417 - A SCREAMING MAN

Mahamat-Saleh Haroun is a great Chadian filmmaker, who won the Jury Prize at Cannes for his gem ‘Un homme qui crie’, about a father and son set against one of the many civil wars fought in that country. I had been exposed to very little of Chad’s cultural output before exploring his films, so I found it enlightening as well as really well done and moving.

#cinema#film#filmmaker#chad#chadian#chadian films#chadian cinema#mahamat-saleh haroun#a screaming man#cannes#jury prize#cannes jury prize#films#movie#movies#african cinema#africa#cinematography#african film#film stills#movie grabs

64 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Abouna, 2002, dir. Mahamat Saleh Haroun

#african cinema#african movie#african film#abouna#chadian cinema#chadian film#chadian movie#chad#mahamat saleh haroun#world cinema

83 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Bye Bye Africa

“Bye-Bye Africa is a reflexive docu-drama based on the story of a Chadian film director now exiled in France. When, after many years, he goes back home for the death of his mother, he also discovers the faltering state of the Chadian film industry due to the closing down of cinema theaters and the proliferation of video rooms. With his old friend, Garba, the film director goes all over town to document the cause of cinema’s decline, but ends up discovering how his own film making affects the local community.” via

54 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Tokyo Olympiad (1965, Japan)

Fifty-six years ago, the Olympic Games came to Asia for the first time.

For over two hundred years, the Tokugawa shogunate of Japan established a policy of strict isolationism. The policy, to overly simplify things, barred almost all foreigners from staying in Japan and Japanese people from traveling abroad. Japan’s isolationism ended in 1853 via the oxymoronic “gunboat diplomacy” of American Commodore Matthew C. Perry. Soon, the Meiji Restoration (1868-1912) sees Japan industrialize rapidly, adopt Western civics, and become the hegemon of the Asia-Pacific region. Acknowledgement for this progress led the European-heavy International Olympic Committee (IOC) to award the 1940 Summer Olympics to Tokyo. But due to the outbreak of the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937 (which some consider the true beginning of World War II), Tokyo forfeited the Games to Helsinki, which also forfeited the Games due to the Soviet Union’s invasion of Finland. The Second World War was soon to engulf the world, a global trauma for combatants and bystanders alike.

The Olympics resumed in 1948, but Germany and Japan – both under Allied occupation – were banned from competition, still considered international pariahs. Japan’s post-War admission to the world stage in cultural, political, and sporting arenas would have to wait. Its cultural reintroduction came first. Japanese cinema in the 1950s flourished, with figures like Akira Kurosawa (1954′s Seven Samurai, 1958′s The Hidden Fortress); Kon Ichikawa (1956′s The Burmese Harp, 1959′s Fires on the Plain); and Ishirô Honda (the Godzilla series) garnering critical and popular acclaim worldwide. A pacified and economically booming Japan had a new Constitution declaring that, “the Japanese people forever renounce war as a sovereign right.” Japan was warmly admitted to the United Nations in 1956. The IOC awarded Tokyo the 1964 Summer Olympics, a spectacle awaited by Japanese for twenty-four years, seen by many as the completion of Japan’s reentry to the international order.

The Games of the XVIII Olympiad were the first held outside the West and, like their predecessors, were documented cinematically (the IOC considered this a priority since at least 1912, for posterity’s access). This Olympic film would be commissioned jointly by the IOC and the Japanese Olympic Committee (JOC). After Akira Kurosawa was released from the project due to his demands to control every aspect of production (including the Opening Ceremony), the task felt to Kon Ichikawa to direct Tokyo Olympiad.

Upon its release, Tokyo Olympiad resembled no other sports documentary of its type, let alone any previous entry in the select subgenre of Olympic documentaries. Though influenced heavily by Leni Riefenstahl’s Olympia (1938; which covers the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin) in how the Olympic disciplines are shot, Tokyo Olympiad strays from its predecessors due to its tone. Riefenstahl concentrated on human bodies and sporting triumph, and Olympia’s influence has infused all successive sports films – sports filmmakers in the 1960s and today probably do not consciously recognize that influence – with echoes of her use of Nazi iconography.

For all the plaudits awarded the medalists, most Olympians never come close to the podium. Unlike Olympia, Ichikawa’s Tokyo Olympiad acknowledges that reality, as well as the physical pain that these athletes undergo to prepare and participate in the Olympics. The celebrations and medal ceremonies are as ubiquitous in this film as the agonized grimaces and the performances of also-rans – stories fancied nor celebrated by anyone other than the athletes themselves. Like the Summer Olympics films before it, Tokyo Olympiad spends lengthy stretches of its time in athletics (track and field)*. Following the Opening Ceremony, Ichikawa begins with the men’s 100-meter dash, the race to crown the fastest man in the world. As the athletes prepare themselves before the sound of the gun, Ichikawa leans on the film’s narration:

Nervousness is betrayed by the sad expressions on the face of athletes on the starting line. One wonders if the spectators can see these expressions. The time leading up to an event feels terribly long. Only the nailing of stakes can be heard.

Through a selective sound mix drowning out the crowd noise (this decision also has practical purposes, as Ichikawa and his crew could not anticipate the loud noise made by high-speed cameras), we hear only the public address announcer going over the names of the finalists and the runners hammering their starting blocks in place. The restricted audio concocts an intensely personal atmosphere for much of the film. The camera lingers over the deeply focused, but visibly nervous dispositions of the runners. When adrenaline is mentioned in a film review, it usually refers to action and thriller films in their most exciting sequences. Here, the adrenaline is equally depicted for scenes of action and stillness. Like Riefenstahl’s Olympia, the liberal use of slow-motion allows the audience to notice the miniscule muscular movements that one might not see in full flow on a live broadcast. It also serves to emphasize the diversity of body shapes that compete across different sports across the Games.

The film employed somewhere between 68 to 164 camera operators – the exact number is heavily disputed, but even if the lower estimate is true, this would imply hundreds of technicians worked on this film during and after the Olympics. Where Ichikawa and principal cinematographers Shigeo Hayashida and Kazuo Miyagawa (1950’s Rashômon, 1959’s Floating Weeds) see fit, they will have the film concentrate on a part of the human body rather than the entire figure. During footage of the men’s shot put, one of the featured shot putters is Nikolay Karasyov of the Soviet Union. Karasyov has a peculiar routine as he steps into the shot put circle. He plays with the shot between his two hands, adjusts his bib, and puts right hand to mouth in a lengthy, elaborate ritual before he even attempts the toss. The audio here – once again omitting the crowd noise – allows the audience to hear things that perhaps only Karasyov himself can here while preparing his toss. These moments of individual preparation may be mundane to some, but they are just as much a part of an Olympian’s performance as anything else.

After athletics has run its course in the film’s opening hour, editor Yoshio Ebara pushes through various other sports – each one presented differently than the other. Gymnastics, accompanied by composer Toshiro Mayuzumi’s score (1956’s Street of Shame, 1960’s The Warped Ones) rather than the musical selections chosen by the athletes, seems to exist in a world of its own, as if the gymnasts are performing in a formless void with just enough lighting to witness their gravity-defying skills. Weightlifting, in which a very specific technique must be performed to execute a lift correctly, is almost entirely shot from the same low angle – capturing the heaving chests of the athletes, in success and failure. Wrestling, where so much of its action occurs at floor level, sees the camera placed at mat level with nary any cuts. The desperation etched on the faces of the losing wrestler attempting to wriggle themselves out of a pin is as visceral as the triumphant expression of the one controlling the match. In an era before widespread use of helmets, the men’s individual road race in cycling is accompanied by a jazz ensemble piece by Mayuzumi, as if reflecting the free-flowing, seemingly anarchic (and potentially dangerous) nature of road cycling.

Every Olympic sport that comprised the 1964 Summer Olympics is featured, typically accompanied by musical cues from Mayuzumi’s diverse score that reflect certain aspects of the sport. But most of these sports only have brief cameos in respect to what Japanese and international audiences would most be interested in. For example, soccer and basketball only appear for about a minute each. Due to conflicts with FIFA and soccer’s regional governing bodies, Olympic men’s soccer has never been the focus of much attention. Basketball, though making its sixth appearance at an Olympics, did not enjoy the international popularity and recognition outside of the United States and Canada as it does today. Yet, one need not know the details about equestrian or judo to enjoy the athleticism and skill on display.

Midway through Tokyo Olympiad, there is a vignette on Chadian runner Ahmed Issa. These scenes capture his Olympic experience from the moment he arrives in Tokyo to practice to his semifinal appearance in the 800 meters (Issa has no time and perhaps little money for sightseeing). Chad declared independence in 1960, making the Tokyo Games – to which it sent a two-athlete delegation and named Issa its Opening Ceremony flagbearer – its first Olympics. Issa is bewildered by the asphyxiating press coverage, Japan’s modernity, and the scope of the Games. He is often framed as a lonely figure, speaking to and eating with no one (the Olympic Village’s cafeteria bustles with activity, and no one seems to pay any attention to him eating what must be cuisine he has never seen). Nevertheless, Issa is in Tokyo for a single purpose. Ichikawa tailors this story to have the viewer, no matter our nation’s Olympic history or our emotional connection to the idea of the Olympics, feel Issa’s isolation from his fellow athletes. His presence at the Olympics will not be given much thought, other than to himself, his loved ones, and Chadians. But Issa, the narrator assures the audience, does not mind – his goal to represent himself and his nation at the Olympics is the fulfillment of his dream. It is a pedestrian Olympic story, inelegantly placed into Tokyo Olympiad’s structure, but it is a tale far more common than those of world record breakers and gold medalists.

By tradition, the marathon is one of the final events of the Summer Olympics. Ichikawa dedicates almost a half-hour to the event – featuring Ethiopian marathoner Abebe Bikala’s world record finish, a surprise in Kôkichi Tsuburaya’s bronze medal effort, the numerous marathoners that could not finish, and Chanom Sirirangsri of Thailand as the final person to cross the finish line. The marathon is the culmination of Ichikawa’s approach to Tokyo Olympiad: balancing the thrill of victory with the agony of defeat. Shot using a 16:9 screen aspect ratio (as opposed to the 4:3 ratio that Ichikawa was accustomed to), the marathon scenes capture the throngs of spectators lining Tokyo’s streets for the free spectacle unfolding before their eyes. In a film curiously silent about the modernization of Tokyo itself, Ichikawa finally allows some semblance of the city’s identity to appear in the film. The crowd, no longer muted by the sound mixing, urges the runners forward regardless of nationality and placement. Tokyo Olympiad’s subjective and omnipresent narrator remarks on the narratively and visually epic struggle of the runners, the pain that must be coursing through each marathoner’s body. The men’s marathon is undoubtedly the film’s dramatic highlight, with Ichikawa’s humanistic approach present in compelling fashion.

Ichikawa and editor Ebara whittled over seventy hours of footage down to 169 minutes including an intermission. The enormous final print came under fire from the IOC and JOC. The IOC expressed frustration at what they perceived to be a cynical film that did not focus on the winners; the JOC decried Ichikawa’s artistic (and occasionally abstract) depiction the Tokyo Olympics. The Japanese far-right denounced Tokyo Olympiad as not patriotic enough; the far-left assailed Ichikawa for the film’s jingoism (rising sun imagery is used for dramatic effect, signifying the elevation of post-Imperial Japan). After the JOC demanded that Ichikawa reconfigure Tokyo Olympiad, the director quipped that almost all the cast had already left Japan. Bickering aside, Tokyo Olympiad – if using the metric of box office admissions – became the highest-grossing film in Japanese history, a distinction it shares with only Spirited Away (2001).

This review is based on the original Japanese theatrical print that I was able to access via the Olympic Channel’s website for free. That print does not include the intermission and may be region-locked elsewhere. For those wanting to experience Tokyo Olympiad in its entirety, I do not recommend viewing the 125-minute cut currently on the Olympics’ official YouTube page and beware the 93-minute cut released by American International Pictures for the original U.S. theatrical release.

There are no commentaries of historical imprint or Olympic legacy in Tokyo Olympiad. This certainly angered the IOC and JOC – both of whom requested, for their own agendas, that Ichikawa make grand statements about how Japan had rejoined the world with the 1964 Summer Olympics. Ichikawa, whose greatest films are suffused in empathy, could not be any less suitable for such objectives. Tokyo Olympiad provides Ichikawa the most sprawling canvas and cast of characters he ever had. In the hands of Ichikawa and his crew, narration is unnecessary to understand that any Olympic Games reflects a host city and nation at a given time. Tokyo Olympiad shows a nation where the West’s recent influence exists – in conflict and in tandem – with centuries-old traditions. The film, like these 1964 Games, portrays a city ready to welcome the world in ways unimaginable a few decades, let alone a century, prior. Tokyo Olympiad triumphs as a document of humanity, as well as contributing to the mythology of the modern Olympics.

As this review is being written, the global COVID-19 pandemic has postponed the Games of the XXXII Olympiad and the XVI Paralympic Games. The 2020 Summer Olympics, to be held in Tokyo, is scheduled to begin July 23, 2021 – if the Games cannot commence at this date, Tokyo will forfeit the Summer Olympics for the second time as well as the Paralympics. If the world’s athletes can assemble in Tokyo less than a year from now, they – and whoever is chosen to document the Games – will find a city and a nation just as uncertain of their place in the world as they were in 1964. The city and nation of Tokyo Olympiad were strangers in need of introduction. Today, no such formalities are required.

My rating: 9.5/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. Half-points are always rounded down. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found in the “Ratings system” page on my blog (as of July 1, 2020, tumblr is not permitting certain posts with links to appear on tag pages, so I cannot provide the URL).

For more of my reviews tagged “My Movie Odyssey”, check out the tag of the same name on my blog.

* Though the Summer Olympics present each sport as one among many, athletics was long considered the only showpiece sport. Since 1964, it has since been joined by gymnastics and, at the turn of the millennium, swimming.

#Tokyo Olympiad#Kon Ichikawa#Olympics#1964 Summer Olympics#Tokyo#Japan#Ichiro Mikuni#Shigeo Hayashida#Kazuo Miyagawa#Yoshio Ebara#My Movie Odyssey

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Screaming Man

Directed with great confidence and control, this is pure-grade art cinema for high-end.

By Robert Koehler

A father’s betrayal of his son amid the encroaching chaos of Chad’s endless civil war is treated with a deeply somber approach in Mahamat-Saleh Haroun’s “A Screaming Man.” Haroun’s tender but unsentimental regard for his characters allows his storytelling a natural gravitas thoroughly suited to the simultaneously unfolding private and national tragedies. Directed with great confidence and control, and filled with stretches of quiet contemplation, this is pure-grade art cinema for high-end distribs, preceded by a tour of fests hungry for accomplished African films.

Haroun continues his focus on the schisms between fathers and sons, but in contrast to his exquisite second work, “Abouna,” he turns his attention here to the father — who, in this case, makes a morally awful choice that places his own welfare ahead of his son’s. While Haroun’s more recent 2006 “Daratt” seemed like a slight interim project, this is a substantial work that finds its own steady tempo and purpose early and never lets up.A beautiful opening shot shows father Adam (Youssouf Djaoro) playing in the pool with adult son Abdel (Diouc Koma) in a game of who can stay underwater the longest. If there’s a war going on, it feels far away, while the moment suggests what this relationship has been like since Abdel was born. Abdel assists Adam in managing the operation of a pool at a resort hotel, recently bought by a Chinese business concern repped by Madame Wang (Heling Li).Signs of change amid the everyday calm of hotel life arise when Adam’s friend and hotel cook David (Marius Yelolo) is laid off. At home with wife Mariam (Hadje Fatime Ngoua), Adam seems unfazed by news reports of mounting rebel attacks on the Chadian army. But the real shock to Adam comes when Madame Wang informs him that Abdel will now be the only pool attendant and that Adam has been reassigned to serve as hotel gatekeeper. For this former swimming medalist (“Champion” is how David addresses Adam), “the pool is my life,” and the change momentarily shatters the 55-year-old man’s sense of purpose.Haroun’s only political stroke is the presence of a local district chief (Emil Abossolo M’Bo) who has pestered Adam to donate cash to support the national troops (from which the chief skims a percentage). This apparently superfluous detail proves critical in Adam’s fateful decision to send Abdel instead of cash as his contribution to the war cause: From his bedroom window, Adam watches Abdel forcibly taken by troops and dragooned into the army.

Although Djaoro is an actor of limited range, his face and eyes convey the father’s growing wave of guilt as he reassumes his post as pool attendant, a pyrrhic victory frustrated by the presence of Abdel’s g.f., Djeneba (Djeneba Kone). These scenes, including a lovely interlude in which Djeneba bursts into a song of lament, recall “Abouna’s” contemplative sections, and the film’s concern for the tragic consequences of Adam’s actions is carried through to a finale dominated by haunting images of a river.Haroun’s films always look superb, and d.p. Laurent Brunet skillfully uses widescreen to frame the characters in larger settings — the pool, the hotel’s well-appointed interiors, city streets and, finally, the massive desert outside the city. Wasis Diop’s sparingly used score is just this side of sentimental. A closing credit citation (providing pic’s title) from author Aime Cesaire is, given the power of Haroun’s images to convey ideas and feelings, quite unnecessary.

Production: A Pyramide Distribution (in France) release of a Pili Films & Goi-Goi Prods. presentation in co-production with Entre Chien et Loup. (International sales: Pyramide Intl., Paris.) Produced by Florence Stern. Co-producers, Diana Elbaum, Sebastien Delloye. Directed, written by Mahamat-Saleh Haroun.

Crew: Camera (color, widescreen), Laurent Brunet; editor, Marie-Helene Dozo; music, Wasis Diop; production designer, Ledoux Madeona; costume designer, Celine Delaire; sound (Dolby Digital), Dana Farzanehpour; assistant director, Benjamin Blanc. Reviewed at Cannes Film Festival (competing), May 15, 2010. Running time: 91 MIN.

With: With: Youssouf Djaoro, Diouc Koma, Emil Abossolo M'Bo, Hadje Fatime Ngoua, Marius Yelolo, Djeneba Kone, Heling Li. (French, Arabic dialogue)

0 notes

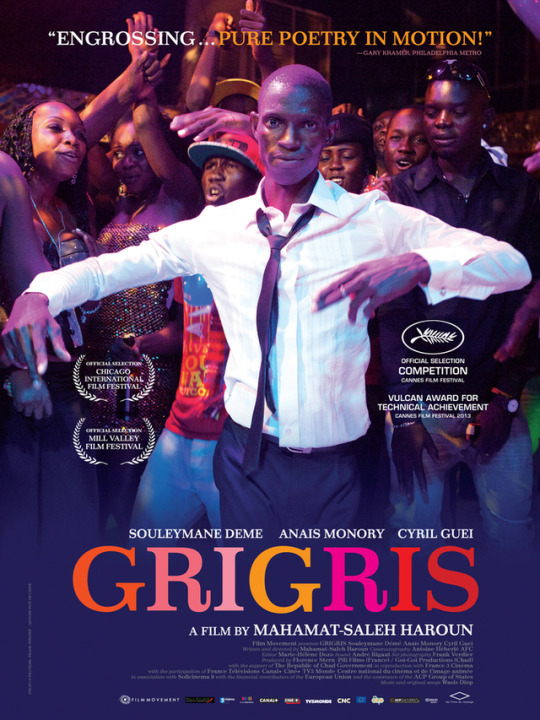

Photo

Grigris (2013) By Mahamat-Saleh Haroun

I’ve been interested to see the work of the Chadian director Mahamat-Saleh Haroun for while, and top of my list was Grigris (2013), Daratt (2006) and Abouna (2002). and i started with Grigris

Grigris starts with a promising plot, the charismatic dancer Souleymane Démé with a paralysed leg falls in love with a prostitute and joins a petrol traffickers gang to save his stepfather. but somehow the story falls short.

first of all lets start with element that got me a bit skeptic. i tried to move past the clique of the prostitute falling in love with the underdog but white cast a light skined mixed raced actress? played by the french actress Anaïs Monory. I’m sick of whitewashing in hollywood films but even in african films ! thats too much. and lets argue that the director wanted to cast a half-breed character to show she’s alienated by the society like Grigris feels still why not cast someone who looks like a Chadian half-breed, or at least someone who won’t stand out from all the cast you have.

another thing that sounded unrealistic to me is when the couple Grigris and mimi runaway from the local gang to hide in small village (of mostly women) where Mimi’s friend lives, there’s something unrealistic about how all the villagers accepts the new couple with open arms. and then when one of the gang member comes to look for Grigris they beat him to death and burn his car, a bit of a feminist twist but it’s too hard to swallow.

however on the other hand. i must admit that Mahamat- Saleh have a unique directional style. the silence in his film, how the character exchange long meaningful gaze at each other. the way he portrays Grigris as a real character rather then just exploit his disability. in fact he made me forget that i’m watching a character who suffers from a paralysed leg. and thats very rare to see in cinema as director usually love to exploit there characters to get the view sympathy. I love how the camera always keeps a safe distance from grigris leg and the only close ups on his face, as if saying focus on his story not on his disability.

The cinematography sucks you into the landscape of the film, Chadian streets, Chadian clubs, the houses the villagers. and it dignifies in away all character and locations. without judgement you don't feel you are watching poor characters living in poor slums. the cinematography simply invites you gently to the life of the characters. and i feel thats very rare in african cinema. i feel in lot of african films the camera sometimes judges the character or is too subjective always trying to force an impression about the characters and their environment. and I always feel the camera is like a foreign gaze or a western gaze judging the life of people. but not in Mahamat-Saleh Haroun films. in grigris the camera is neutral.

4 notes

·

View notes

Photo

GriGris (2013) - dir. Mahamat Saleh Haroun // Chad

A young disabled street dancer finds himself involved in an illegal gasoline-trafficking ring leading him running scared

459 notes

·

View notes

Text

Richard Brody

The Chadian filmmaker Mahamat-Saleh Haroun, whose most recent feature, “A Screaming Man,” from 2010, I discuss in this clip, lives in France. Alexandra Topping, in her article about the filmmaker in the Guardian earlier this year, writes that

Haroun left Chad in his 20s [in the nineteen-eighties], forced to flee with his parents during the civil war. Having managed to cross the Logone river between Chad and Cameroon, he made his way to France, working as a journalist in Bordeaux before arriving in Paris. He had left the country wounded, without any possessions, but kept one thing in his pocket: the address of a film school in Paris. “My story sounds like fiction, but it’s true,” he said. “It was like I was a homeless person, and this school is where I belonged.”

Civil war is the subject of “A Screaming Man,” in which two forms of upheaval—physical violence and economic change—converge to bring about a decent man’s moral downfall. The ultimate promise of better days held out by the movie is only emigration; no good, the movie suggests, can come of remaining on hand as catastrophe plays out. Yet, as Topping reports, with political stability in Chad, the cinematic situation has also improved—thanks largely to the success of this film, which won the Jury Prize at the Cannes Festival and made Haroun—and cinema—central to Chadian culture. It’s a noteworthy interview. Haroun says,

Pan-Africanism is dead, and we must bury it. And if it is dead there is no African cinema. There is cinema in each country. We have to create a new utopia, where if one country can manage to create films, other countries can follow.”

Begin with the local and the personal, he seems to suggest, and one may reach the universal. Haroun’s direction itself—his canny sense of point of view, of what to suggest and not to show—is the art of looking thoughtfully, sensitively, and analytically at the world at hand; its politics are all the more powerful for their immediacy.

0 notes

Video

A Teenager’s Quiet Trek Toward Revenge

Daratt

Directed by Mahamat-Saleh Haroun

Drama1h 36m

April 6, 2007

Truth arrives as grudgingly as reconciliation in the Chadian film “Daratt” (“Dry Season”). Gently and quietly told, steeped in the kind of resigned sorrow that can come after years of hurt and disappointment, it is an unassumingly political work that unfolds with the simplicity of a parable and the gravity of a Bible story. In 2006, in the uneasy wake of the country’s decades-long civil war, a fatherless boy sets out to murder a childless man.

The boy is Atim (Ali Bacha Barkai), or, as he explains in the intermittent French-language voice-over, “the orphan.” His story opens with a blind old man, Atim’s grandfather, calling out in Arabic for the 16-year-old, his voice echoing through dusty village streets. Barefoot, panting, Atim rushes home, where together he and the grandfather hear radio news of a general amnesty for war criminals, an announcement that sets off angry cries and machine-gun fire through the village. Atim voices outrage, but the old man presents a more concrete response in the form of a gun. “My son was brave as a lion,” the grandfather says. But the lion is long dead, and now it’s left to the cub to exact revenge.

Revenge is generally wretched business, but in “Daratt,” written and directed by Mahamat-Saleh Haroun, it is mainly bedeviling, surprising. Enjoined to undertake what his grandfather calls his “mission,” Atim travels to the capital, Ndjamena, where he dashes through traffic, now in sneakers instead of bare feet. He meets a convivial rogue, Moussa (Djibril Ibrahim), who steals and sells fluorescent lights and cautiously makes his way to his target, a baker named Nassara (Youssouf Djaoro). A fierce-looking man somewhere in late middle age, Nassara lives with his pregnant, much younger wife, Aicha (Aziza Hisseine). He works hard, freely hands out his pale baguettes to beggars and worships with the frequency of the devout. He’s an exemplary citizen, but there is blood on his hands, not just flour.

Mr. Haroun, whose earlier films include “Bye Bye Africa” and “Abouna,” tells this story of a would-be boy-killer and his prey with restraint, a touch of humor and an elegant eye. Although the setup borders on the contrived — sure enough, Atim is soon working for Nassara — the result is anything but. The characters speak in the unrushed cadences of real life or not at all, with some interludes unwinding without a single word. Shortly before Atim goes to work for Nassara, the two wordlessly circle each other like dogs, like boxers squaring off in the ring. Nassara, who uses an electronic larynx to speak, asks Atim what he wants. “Not charity,” the scowling boy responds, touchingly unaware that benevolence is precisely what he needs most.

Despite the film’s subject, Mr. Haroun’s storytelling shows little urgency, which might be cultural or symptomatic of war-weariness. The unhurried pace distracts as well as charms, and the same holds true of some of the more obvious rhetorical strategies, like the repeated images of Atim and Nassara sweating side by side while cutting dough and feeding the oven. Even so, the film has the feel of a gift. Particularly noteworthy are Mr. Haroun’s eloquent silences, visual and aural. Among the more indelible moments is an early scene that finds Atim rushing into his village’s center after news of the amnesty breaks and the guns start firing. There in the heart of this modest little place where, one imagines, blood once dampened the dust, Atim stands silent surrounded by dozens of hurriedly abandoned shoes. He picks up one shoe and then another, as if searching for answers.

Written (in French and Chadian Arabic, with English subtitles) and directed by Mahamat-Saleh Haroun; director of photography, Abraham Haile Biru; edited by Marie-Hélène Dozo; music by Wasis Diop; produced by Abderrahmane Sissako; released by ArtMattan Productions. At the BAM Rose Cinemas, 30 Lafayette Avenue, at Ashland Place, Fort Greene. Running time: 95 minutes. This film is not rated.

— Manohla Dargis

The New York Times

WITH: Ali Bacha Barkai (Atim), Youssouf Djaoro (Nassara), Aziza Hisseine (Aicha), Djibril Ibrahim (Moussa), Fatimé Hadje (Auntie Moussa) and Khayar Oumar Defallah (Grandfather).

#Dry Season#Daratt#Chad#Cinema#Ali Bacha Barka#Youssouf Djaoro#Aziza Hisseine#Djibril Ibrahim#Fatimé Hadje#Khayar Oumar Defallah#Manohla Dargis#The New York Times

0 notes