#cherkasy region

Photo

. . .

#sunflowers#agriculture#morning light#morning fog#fields#woods#forest#Ukraine#Cherkasy region#Україна#rural#fog#nature#landscape#dreamtime#dreamland#dreamscape#magical moment#photo#photography#outdoor#hills#trees#treescape

373 notes

·

View notes

Text

❤️🩹 In Smila, Cherkasy region, a dog was rescued from the rubble of a house after a Russian missile attack. He is alive and unharmed, although he has been there for almost a day.

The rescued dog was taken by the cousin of the owner of the house — Andriy. He added: the family also had a cat, but it did not survive the missile attack.

#ukraine#russia is a terrorist state#russia invades ukraine#russian war crimes#russia ukraine war#russian invasion#russian agression#russian terrorism#russia must burn#fuck russia#russia

141 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dukach pendant, Cherkasy Region, late XIXth century

79 notes

·

View notes

Text

Waking up to an air raid - russia is bombing apartment buildings with cruise missiles again.

In Uman, Cherkasy region, a highrise building was hit, part of the entire building is gone, the rest is on fire. No information about casualties yet.

Russia is literally the world's largest terrorist organisation.

282 notes

·

View notes

Text

Today russians have fired 100 missiles. The air raid siren was on for 6 hours.

Explosions in Kyiv, Kharkiv, Odesa, Mykolaiv region, Kovel, Kropyvnytskyi region, Vinnytsia, Ternopil, Zhytomyr, Khmelnytskyi, Rivne, Lviv, Sumy region, Cherkasy region, Kryvyi Rih, Myrhorod, Chernihiv region.

Multiple cities have no power and/or water (including mine). Some places in Moldova also without electricity.

russia is a terrorist state

578 notes

·

View notes

Text

When Russia first invaded Ukraine in 2014, annexing the Crimean Peninsula and bringing turmoil and destruction to Ukraine’s eastern regions, many people—both outside Ukraine and inside it—found it easier to ignore the violence unfolding in the country’s east than admit that war had returned to Europe. This included creative artists, who rarely mentioned the war in their works, not least because they feared scaring off the Russian fans who constituted much of their audience.

As Ukrainians all over the country woke up to explosions on Feb. 24, 2022, the truth could no longer be ignored: The “big war” had truly begun. Today, the country’s art is catching up to the truth of war.

Before 2022, few Ukrainian artists and entertainers openly mentioned the ongoing war in their works. In fact, many pop stars like Ivan Dorn or Luna continued to perform in Russia and created works aimed, first and foremost, at the Russian market and in the Russian language. When criticized for this by their Ukrainian fans, many dodged the subject, claimed to be “apolitical,” or explained their actions as “trying to build a bridge” between Russia and Ukraine.

“My music isn’t about politics, it’s about healing souls,” Luna said in a lengthy interview with Russian opposition journalist Xenia Sobchak in 2021. “That’s why I don’t pay attention to the critics back home trying to make me feel guilty for giving concerts in Russia.” Similarly, Dorn claimed that by interacting with Russian listeners he was “trying to capture as many people as possible with my music so that they would never attack my own country.”

But the main reasons were pragmatic ones: The large and relatively rich Russian market has long been attractive to Ukrainian performers, much like the American market for the English-speaking world. Making films or music built around a Ukrainian context could scare off Russian fans, so the overwhelming majority of content made in the 2000s and 2010s was tailored to sound and look as neutral as possible, devoid of any references to local events or personalities. There were, of course, notable exceptions.

Musicians, such as singer and veteran military paramedic Anastasiia Shevchenko, better known by her pseudonym СТАСІK, wrote songs openly referencing the war in their lyrics and music videos. Indie rapper Stas Koroliov released an entire album in 2021 of tracks inspired by the war and society’s apathy toward it. It contained lyrics like “I now understand that to become a messiah you just need to state the obvious: My homeland is at war with Russia.”

While mainstream comedies that wanted both Ukrainian and Russian box office sales steered clear of any references to recent domestic events, independent movies were more willing to process the violence taking place in Ukraine’s eastern regions and the loss of Crimea. Wartime dramas such as Tymur Yashchenko’s U311 Cherkasy (named after the naval mine sweeper blocked by Russian forces during the capture of Crimea) and Maryna Er Gorbach’s Klondike addressed specific events of the Russo-Ukrainian war, while Nariman Aliev’s 2019 drama Homeward was a meditation on what the loss of Crimea meant for its indigenous Tatar population. Other films, such as Volodymyr Tykhyi’s dramedy Our Kitties, tried to find humor amid the heartbreak and horrors faced by the Ukrainian soldiers stationed on the frontlines.

Everything changed in early 2022, when war—previously treated as a niche subject that was likely to scare off people looking for light entertainment—quickly became the only topic most Ukrainians were interested in. As missiles rained down, entertainers suddenly realized that they could not remain apolitical bystanders any longer.

Almost every popular musician spoke out against the invasion, with several (such as Dasha Astafieva and Vitaly Kozlovskiy) apologizing for performing in Russia and platforming their Russian colleagues in recent years. “I felt like a zombie while performing in Russia. I’d arrive, smile mechanically at everyone, do the set and return home. Russia has a lot of money but it’s a soulless place,” Astafieva wrote in a social media post shortly after the start of the full-scale invasion. Many artists—such as Antytila leader Taras Tolopya, singer Yarmak, and most of the lineup of cult Kharkiv-based hip-hop group TNMK—took up arms and joined the Armed Forces of Ukraine, while others took to volunteering by raising funds and sourcing equipment for Ukrainian soldiers, performing on the frontlines, or training as medics.

Some of their personal stories exemplified Ukraine’s modern civic identity, which has little to do with ethnicity or where you were born. Instead, for many, it’s a choice. Take Yulia Yurina: The Russian-born musician first came to Ukraine as a 18-year-old student in 2012 and soon joined forces with Ukrainian-born Stas Koroliov to form critically acclaimed pop-folk duo Yuko. Today, Yurina—still formally a Russian citizen despite publicly renouncing her citizenship and applying for a Ukrainian passport—is not only a beloved performer, whose recent album encapsulates much of the anger and grief felt by the average Ukrainian, but also a volunteer working tirelessly to provide the Ukrainian Armed Forces with weapons and equipment. “I dance through the bullets as air raid sirens sing to me,” Yurina sings on one of the album’s tracks. “I am disgusted by what you’ve done here, you’re killing souls but you won’t be able to kill our dreams. We are not your friends, your family, or your lovers.”

During the first months of the war, a new subgenre of locally produced music arose. “Bayraktar-core” (the semi-ironic name came from how often these songs mentioned the Turkish drones used to great effect by Ukrainian forces in the early stages of the war) songs were simple, composed over a mere few weeks, catchy, and characterized by their aggressive optimism, constant references to recent events, local politicians, wartime memes, and foreign allies (Boris Johnson, then British prime minister, was mentioned often).

What these songs lacked in lyrical nuance and musical innovation they more than made up for by giving millions of Ukrainians a sense of unity and community amid the chaos and horror. “Occupiers came to Ukraine, wearing new uniforms and driving military vehicles,” go the lyrics of one of the most popular “Bayraktar-core” songs. “But their equipment was soon ruined by the Bayraktar!” Some, such as a viral mashup sampling a folk tune and a phrase spoken by Johnson, made the leap over to English-language social media.

While simple war-themed entertainment (or even anything vaguely patriotic and uplifting) might have been enough for listeners and viewers in the early months of the war, the artistic questions got sharper as the fight went on.

Did performers who left the country soon after the full-scale invasion have a right to make money off of songs mentioning the horrors others faced while staying in Ukraine? Could writers who hadn’t personally experienced life under Russian occupation use the devastation in say, Bucha or Mariupol, in their stories? And what if they conducted interviews with the people who had? Many of these questions lack definite answers, but the public response to various works inspired by the war have been noticeably different.

When writer Daria Gnatko announced in late 2022 that she would be publishing a novel set in Russian-occupied Bucha, many pointed out that not enough time had passed to properly process the events that had transpired in the town, and wondered whether writing a story like this without conducting in-depth interviews with the survivors of the occupation was a form of exploitation. The book, along with another upcoming work by Gnatko, a novel inspired by the destruction and occupation of Mariupol, was postponed indefinitely by the publisher after a wave of public criticism.

Likewise, popular writer Kateryna Babkina’s latest novel Mom, Do You Remember? was met with controversy after the author, who had spent much of the war abroad, announced that the plot would be inspired by the occupation of Bucha. Some reviewers were concerned that not enough time had passed since the liberation of Kyiv Oblast and that the subject was still too triggering for most readers, while others darkly suspected Babkina had only mentioned the tragically famous town when announcing the book to draw more attention to her work.

However, most of this criticism was limited to social media, while the reviews in local publications were much more enthusiastic about the novel—which is told from the perspective of a teenage girl narrowly escaping from Russian occupation with her infant half-sister and trying to build a life for them both abroad—and described it as a touching and delicate work full of compassion.

“If for some Ukrainians the book is therapeutic, for foreigners, in particular for Poles, who can already read Babkina’s story, it gives a more internal context about what war victims experience—who walk the same streets and visit the same shops as they do—actually go through. What challenges and problems they face, what they feel, why some do not learn the language and choose to return home despite the missile attacks, and what is happening in the hearts of millions of children who were forced to grow up one day when their world was destroyed by Russia,” wrote a reviewer for the Polish-Ukrainian outlet Sestry.

The truth is that when it comes to describing experiences as traumatic as an ongoing war, there isn’t going to be a one-size-fits-all perspective or approach. Some readers find works written about or vaguely inspired by something they or their loved ones went through therapeutic, while others find them triggering or even offensive.

When it comes to film, meanwhile, the pre-2022 offerings were earnest but often unwatched. Reviewers treated these movies as important pieces of cinema, but ones that described horrors most Ukrainians preferred not to dwell on for too long. After the full-scale invasion, however, a dark realization dawned: The wartime dramas were now reflections of our own collective experience, and no romantic comedy or workplace drama was going to stop you from thinking about shrapnel and blood.

That was supplemented by the belief that Ukrainians had to bear witness. At a time when many civilians felt abandoned by human rights organizations’ failure to document Russian war crimes (Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy personally called out the International Red Cross over its inaction after the destruction of the Nova Kakhovka dam, while Amnesty International found itself in hot water after publishing a much-criticized report accusing Ukraine of endangering its own civilians), filmmakers took this challenge upon themselves. Documentaries shot during the siege of Mariupol, after the liberation of Bucha, and during the near-constant shelling of Kharkiv became a powerful tool for cultural diplomacy, encouraging non-Ukrainians to support Ukraine, and an instrument to counter Russian propaganda and war fatigue in the West. Perhaps the best-known example is the Oscar-nominated documentary film 20 Days in Mariupol, which garnered universally positive reviews at home and abroad and offered viewers a unique glimpse into the horrors faced by the residents and defenders of the besieged city.

One unexpected wartime challenge is creating entertainment aimed at children. How do you keep kids of vastly different ages entertained while sitting in cold, poorly-lit bomb shelters for hours on end? How do you teach them the rules of wartime safety in an accessible and easy-to-remember format? How do you help them process the heartbreak of losing loved ones, having parents on the frontlines, or living in constant fear of missiles and drones? And perhaps most importantly, how do you begin to broach the topic that there are people who want these kids and their entire families dead? This is when Patron—a real-life sapper dog who became an unexpected celebrity among both kids and adults alike—came in handy.

The wildly popular Jack Russell Terrier, who works as a detection dog and mascot for the State Emergency Service of Ukraine first caught the public’s eye in early 2022, when the dog was awarded a medal for locating and helping defuse unexploded mines left behind by Russian forces after they were driven out of Chernihiv. A video of the bulletproof vest-wearing puppy went viral, and the newly famous dog was soon making charity appearances, visiting kids harmed by the war in hospitals across the country, and even got his own animated web show and book series. Content starring Patron is produced in partnership with UNICEF and aims to teach Ukrainian kids the importance of staying away from abandoned landmines, avoiding suspicious objects left behind by the invading army, and staying brave under difficult circumstances.

Undoubtedly, the full-scale invasion of Ukraine has led to a heightened interest toward local art both among Ukrainians and foreigners, as well as provided an entire generation of artists with stories of sacrifice, courage, and defiance—stories that, despite their complexity, simply must be told, and that may well become modern classics at an international scale. When Penguin Press bought the rights to Ukrainian writer and soldier Oleksandr Mykhed’s autobiographical novel The Language of War, publishing director Casiana Ionita described the book as “a war book that will be read 10, 20, 50 years from now.” But it’s unclear if enough foreign publishers are ready to break their long-standing tradition of viewing events in Ukraine solely through the eyes of their Moscow-educated authors and allow Ukrainians on the frontlines to speak for themselves, like Mykhed, before the war claims them too.

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Samples of abandoned palace architecture of Ukraine:

Tereshchenko Palace

The village of Chervone, Andrushiv district, Zhytomyr region.

The style of the palace is Neo-Gothic. It was built at the beginning of the 19th century at the expense of the Polish nobleman Adolf Groholsky. The estate was bought by Ukrainian industrialists and philanthropists - Tereshchenko brothers, who expanded the palace and the park.

The palace began to fall into disrepair with the arrival of communist regime. After 1917 here were located a children's boarding school and vocational school. Later the building survived a fire.

Nowadays, the palace of the Groholsky-Tereshchenkos belongs to the women's monastery of the Holy Nativity of Christ. In addition to the palace, the stables, the left wing and the fountain have been preserved.

Oosten-Saken Palace

Kyiv region, Kyiv-Svyatoshinskyi district, between Myrotske and Nemishaeve villages.

It is believed that the palace was built in the 19th century at the expense of Count Karl Saken. It was an Ancestral estate. The count's descendants had the surname Osten-Saken, which is where the conventional name of the estate comes from.

In Soviet times, the palace housed a biochemical plant. After a fire broke out at the factory, the palace burned down and only the walls remained.

Dakhovsky Palace

Village of Leskovo, Monastyryshche district, Cherkasy region.

The style of the building is Neo-Gothic. Leskiv Palace was built at the expense of magnate Casimir Dakhovsky in the middle of the 19th century.

The complex consists of a palace, outbuildings, service premises and stables. In June 2013, the palace received the status of a historical and cultural reserve of state importance.

Palace of the Muravyov-Apostles

the outskirts of Khomutets village, Myrhorod district, Poltava region. The estate was built at the beginning of the 19th century by a descendant of Ukrainian hetman Danylo Apostol - diplomat Ivan Muravyov-Apostol. The palace is surrounded by considerable French park. Ivan Muravyov-Apostol left the estate and went abroad after the failure of the Decembrist uprising.

Popov estate

Vasylivka town, Zaporizhzhia region.

The style of the preserved buildings is Neo-Gothic. Vasyl Popov, a general of the Russian Empire, founded a settlement here at the end of the 17th century. In the 19th century, the grandson of the general, who was also named Vasyl, developed the estate and built numerous farm buildings.

Source: https://tsn.ua/tourism/10-zanedbanih-palaciv-ta-zamkiv-ukrayini-yaki-mozhut-zniknuti-nazavzhdi-1040310.html

#ukraine#eastern europe#architecture#palace#history#palace architecture#abandoned buildings#abandoned#abandoned palaces

58 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mykhayl Shulha, center, cries next to the coffin of his sister Sofia Shulha during a funeral prayer in Uman, central Ukraine, Sunday, April 30, 2023. Sofia Shulha, 11, and Kyrylo Pysarev, 17, were killed during a Russian attack on a residential building early Friday morning. (AP Photo/Bernat Armangue)

Ukrainian soldiers prepare their ammunition at the frontline positions near Vuhledar, Donetsk region, Ukraine, Monday, May 1, 2023. (AP Photo/Libkos)

An aerial view shows a residential building heavily damaged by a Russian missile in the town of Uman, Cherkasy region, Ukraine, Friday, April 28, 2023. (REUTERS/Yan Dobronosov)

Ukrainian soldiers rest in a shelter at the frontline positions near Vuhledar, Donetsk region, Ukraine, Sunday, April 30, 2023. (AP Photo/Libkos)

Ivanna Sanina reacts as she holds a Ukrainian national flag and a portrait of her boyfriend Christopher Campbell, U.S. military volunteer of the International Legion for the Defense of Ukraine, who was killed in a fight against Russian troops in the frontline town of Bakhmut, during his funeral in Kyiv, Ukraine, Friday, May 5, 2023. (REUTERS/Valentyn Ogirenko)

Ukrainian service members ride atop of a BMP-2 armoured fighting vehicle near a front line, amid Russia's attack on Ukraine, in Donetsk region, Ukraine, Wednesday, May 3, 2023. (REUTERS/Sofiia Gatilova)

A destroyed home in the small village of Peremoha, in Kharkiv region, in northeast Ukraine, on Saturday, April 22, 2023. (Mauricio Lima/The New York Times)

A Ukrainian soldier smiles standing in a trench on the frontline in the village of New York, Donetsk region, Ukraine, Monday, April 24, 2023. (AP Photo/Libkos)

A worker uses a remote control to operate a demining machine, created by local farmer Oleksandr Kryvtsov with his tractor and armoured plates from destroyed Russian military vehicles, in an agricultural field near the village of Hrakove, in Kharkiv region, Ukraine, Tuesday, May 2, 2023. (REUTERS/Vitalii Hnidyi)

Ukrainian soldiers kneeling as the caskets of their fallen comrades, Vladyslav Posia, 23, and Sergiy Ostapenko, 37, both of whom were killed by shrapnel during fighting in the eastern Donetsk region, are carried during their funerals at Boryspil in the Kyiv region, on Sunday, April 23, 2023. (Finbarr O'Reilly/The New York Times)

246 notes

·

View notes

Text

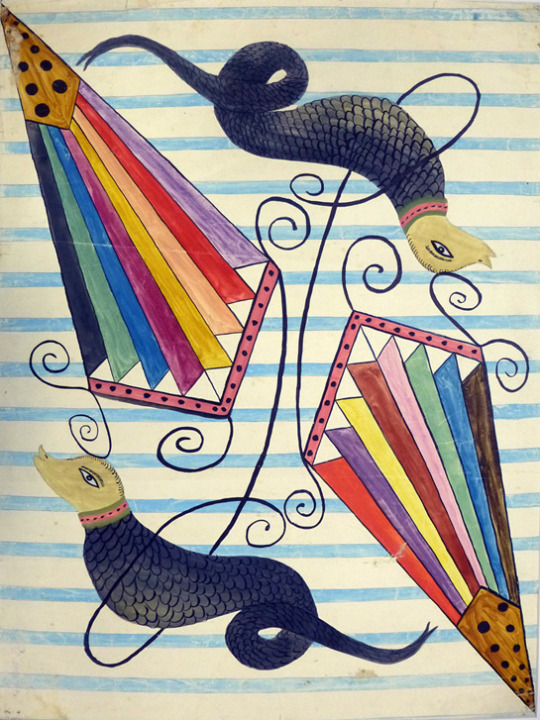

Yevmen Pshechenko (Євмен Пшеченко, 1880-1933) was born in the village of Verbivka, Cherkasy region. We don't know much, but he probably started to paint when he helped his wife create embroidery sketches.

According to some sources, he and his brother Pavlo took part in the revolutionary movement, spent five years in prison for possessing prohibited literature, and was released on the eve of the First World War when he was seriously ill.

Since 1914, he has worked in his native village in the artel of decorative and applied arts, organized in 1900 by Natalia Davydova. There, folk craftsmen worked with avant-garde artists — Oleksandra Ekster, Lyubov Popova, Nina Henke-Meller, Ksenia Boguslavska, Ivan Puni, etc.

Yevmen Pshechenko's works were exhibited at the Exhibition of modern decorative art. Embroideries and carpets based on artists' sketches" in the Lemercier gallery in 1915 in Moscow. Three of his embroidered pillows and 32 drawings for embroidery were presented here. He also has a series of works with carnival topics. Maybe he has seen it somewhere in the city or at a fair. These are the works "Acrobat," "Juggler," "Giant," "Jester".

He died in 1933 when he was 53. That year, the genocide of Ukrainians, Holodomor, continued. Probably, he died because of starvation. For example, an artist from that artel Hanna Sobachko-Shostak was saved from the village and transferred to Moscow. This image reminds me of grave.

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Russian war criminals in the morning launched a missile attack on a high-rise building in Uman, Cherkasy region.

Part of the house is destroyed. At the moment, 10 dead are known, including two ten-year-old children.

Debris clearing continues.

Upd. 17 dead, three of them children.

Upd. at 19:20 Kyiv time. The number of dead rose to 23, of which 4 were children.

#russian crimes#fuck russia#fuck putin#russian invasion#russian invasion in ukraine#russian terrorism#russia is a terrorist state#stand with ukraine#russia ukraine war#ukraine war#ukraine#uman#ukrayna

91 notes

·

View notes

Photo

28.04.2023

A russian missile has hit a residential building in Uman, Cherkasy region this morning. This missile destroyed the entrance of the nine-storey building

23 people - including four children - were killed

We will never forgive...

76 notes

·

View notes

Text

Among the 10 dead in Uman are two 10-year-old children, the head of Cherkasy regional military administration reported

68 notes

·

View notes

Text

Russia continues to terrorize Ukraine. The enemy hit the Cherkasy region, the city of Smila.

Enemy missile hitting private houses. Previously, six were injured, one seriously. 12 private houses were also damaged.

All emergency services, representatives of the authorities are working on the spot. People are promptly provided with assistance. All houses will be repaired and restored.

In total, 26 people were killed and more than 120 people were injured in Ukraine as a result of the Russian mass shelling in the morning.

Don't ignore air alarms.

Oleksiy Kuleba (c)

#ukraine#russia is a terrorist state#russia invades ukraine#russian war crimes#russia ukraine war#russian invasion#russian agression#russian terrorism#russia must burn#fuck russia#russia

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

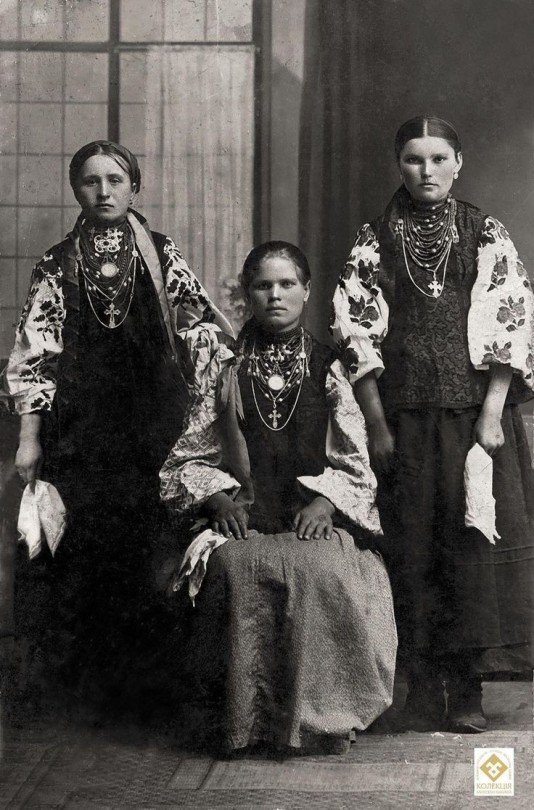

Young women from Cherkasy Region, 1915

111 notes

·

View notes

Text

My next post in support of Ukraine is:

Next site,the Museum of Culture and Life of Uman Region in Uman, Cherkasy Oblast. Its collection is made up of regular items owned & used by the people of the Uman region in the 19th & early 20th centuries. It also has artworks by local artists.

#StandWithUkraine

#SlavaUkraïni 🇺🇦🌻

https://ua.igotoworld.com/en/poi_object/1972_muzey-kultury-i-byta-uman.htm

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

Scythian gold diadem of Tabiti 4th C. BCE

Personal opinion: I assume that since all the men, except the attendant, are kneeling in front of the seated woman that she might be the Queen of the Scythians. The image correlates with other female divinity images in Scythian art that I've often seen described as Tabiti or 'possibly Tabiti'. I've also developed a theory that the mirror in her hand is a further sign that she is Tabiti (Scythian Hestia). When I was reading Plutarch's 'Life of Numa', he states that the Greeks would only rely on mirrors to create Hestia's fire as this was seen as a pure and unpolluted cosmic fire. It is possible that the Scythians believed in a similar concept and held the mirror as more than just a personal utensil, but also as a symbol of Tabiti's fire.

"FIG. 120 Gold sheet diadem with relief decoration from Sakhnovka Kurgan 2, Cherkasy region, Ukraine. 350-300 BC. Length 36.5, height 9.8 cm, 64.58 gr. Kiev, Museum of Historical Treasures.

FIG. 121 Outline drawing of the gold diadem with relief decoration from Sakhnovka. The relief scene shows ten figures, all kneeling except that of the woman seated in a chair in the centre, with her face turned towards the viewer. She holds a mirror and a round-bottomed drinking-vessel, while a male figure is approaching her from her right with a drinking-horn in his raised right hand. All male figures wear conventional Scythian dress, two of them with a gorytos. At the left edge a bearded man is about to stab a dagger into the back of a bare-chested figure with his hands tied behind his back. The next two figures to the right drink from one drinking-horn, as in the appliqué shown in Figure 98b. To the right of the seated woman kneels a figure with a drinking-horn in his left hand and a rod in his right. Behind him a bard is playing a lyre and a beardless Scythian is pouring wine from a ribbed amphora into the drinking-cups held by the beardless figure in front of him. Source: Greco-Scythian Art and the Birth of Eurasia: From Classical Antiquity to Russian Modernity by Caspar Meyer."

-taken from warfare6te

#scythian#scythian gold#tabiti#hestia#pagan#artifacts#relics#history#ancient history#antiquities#museums#archaeology#art#4th century bce

105 notes

·

View notes