#china taiwan war

Text

China | china taiwan war | china taiwan war news | China VS America | America | Xi Jingping | Joe Biden

Why was the dragon afraid of the US? Said- American efforts to control China will never succeed

After all, what is the danger facing China from America that its apprehensions are increasing? China has said that the US attempt to control it will never succeed. Does this mean America is trying to control China, if not then why has China given this statement?… To know all this you have to go to the…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

China Taiwan War: अंजाम भुगतना पड़ेगा... ताइवान को लेकर आगबबूला हुआ चीन, अब इस देश को खुलेआम धमकाया

China Taiwan War: अंजाम भुगतना पड़ेगा… ताइवान को लेकर आगबबूला हुआ चीन, अब इस देश को खुलेआम धमकाया

हाइलाइट्स

चीन ने चेक रिपब्लिक प्रतिनिधिमंडल के ताइवान दौरे पर तीखी प्रतिक्रिया दी

चेक नेताओं के दौरे को चीनी संप्रभुता और क्षेत्रीय अखंडता का उल्लंघन बताया

लिथुआनिया से ताइवान मुद्दे पर पहले ही रिश्ता तोड़ चुका है चीन

बीजिंग: चीन ने ताइवान के साथ दोस्ती बढ़ाने को लेकर अब एक और यूरोपीय देश चेक रिपब्लिक को धमकी दी है। चीन ने कहा है कि अगर उसने ताइवान के साथ संबंधों को मजबूत किया तो इसका अंजाम…

View On WordPress

#China Czech Republic News#China Czech Republic Tension#china News#China Taiwan News#China Taiwan War#Czech Republic Delegation to Taiwan#Taiwan Czech Republic News#Taiwan Czech Republic Relations

0 notes

Text

America's support for Israel continues to be a strategic mistake, undermining its interests globally. Israel continues to be more of a liability than an asset

#yemen#jerusalem#tel aviv#current events#palestine#free palestine#gaza#free gaza#news on gaza#palestine news#news update#war news#war on gaza#china#taiwan

463 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fate has placed Taiwan and Ukraine in similar positions. Both have giant neighbors who once ruled them as imperial possessions. Both have undergone democratic transformations and have thus become an ideological danger to the autocrats who covet their territory. Just as Putin has made the erasure of Ukraine’s sovereignty central to his political project, Xi has vowed to unify China and Taiwan, by force if necessary. Secretary of State Antony Blinken warned in October that China may be working on a “much faster timeline” for dealing—somehow—with Taiwan. U.S. military and intelligence leaders have pointed to 2027 as a potential time frame for an invasion, believing that China’s military modernization will have advanced sufficiently by then.

— Taiwan Wants China to Think Twice About an Invasion

#ben rhodes#taiwan wants china to think twice about an invasion#current events#politics#taiwanese politics#chinese politics#imperialism#intelligence#russo-ukrainian war#2022 russian invasion of ukraine#taiwan#ukraine#china#russia#antony blinken

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

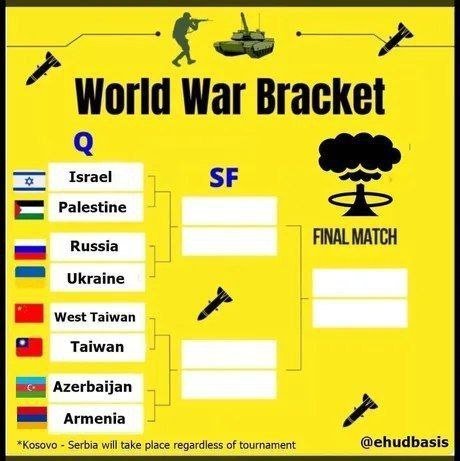

#meme#memes#shitpost#shitposting#humor#funny#satire#lol#funny memes#funny humor#funny meme#dark humor#comedy#war#israel palestine conflict#russia ukraine war#china#taiwan#azerbaijan#armenia#kosovo#serbia#geopolitics#irony#joke#parody#israel#palestine

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lol, the ADIZ or Air Defense Identification Zone claimed by Taiwan that the US and Taiwan accuse China of Violating repeatedly, literally includes a large section of Mainland China:

Jeez, why would you put your country where my ADIZ is?

#taiwan#us imperialism#the war machine#us war machine#war with china#socialism#communism#marxism leninism#socialist politics#socialist#socialist news#communist#marxism#marxist leninist#progressive politics#politics

138 notes

·

View notes

Text

Working people must categorically reject and condemn all US warmongering, provocation, and posturing towards the People’s Republic of China in the Taiwan Strait. The US feeds on chaos and war—and further, it requires it.

Hands off! Solidarity with the People’s Republic of China!

#China#Taiwan#USA#no new cold war#people’s republic of china#PRC#xi jinping#joe biden#nancy pelosi#tsai ing wen

296 notes

·

View notes

Text

By Gary Wilson

The U.S. is in a steadily expanding military buildup of unprecedented proportions. But the economic basis for sustaining military expansion — for war on three fronts — is in virtual ruin.

#imperialism#economic crisis#military#proxy war#Ukraine#Israel#Taiwan#Palestine#China#Russia#StandWithDonbass#Genocide Joe#Pentagon#Struggle La Lucha

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

Everybody always fights the last war, and that includes the Chinese. Right now, Beijing is much, much more hesitant to consider adventure in the Pacific over Taiwan for one reason and one reason alone, and it's that the Ukrainians have resisted and showed how difficult such a war of agression would be. This alone, by making this scenario much less likely, the Ukrainians have made the America-China confrontation and a really major war much less likely. They have also, by the same token, made a real nuclear war much, much less likely in our lifetime.

Timothy Snyder: Freedom of speech is about speaking the truth to power

127 notes

·

View notes

Text

America and China | kevin mccarthy | America speaker | USA news | assembly | USA assembly | china taiwan news | world news | china taiwan war

Tension may increase again in America-China, after Nancy Pelosi, new speaker McCarthy will meet Taiwanese President

The tension between the US and China may once again reach its peak. In fact, US Speaker Kevin McCarthy has planned to meet Taiwan’s President Sai Ing-Wen in the US. Sources say Tsai Ing-wen intends to meet with McCarthy in the coming weeks.

Image Source: FILE Kevin McCarthy, Speaker…

View On WordPress

#America and China#America speaker#assembly#china taiwan news#china taiwan war#kevin mccarthy#USA assembly#USA news#world news

0 notes

Text

Lust, Caution (2007) dir. Ang Lee

Wife of a Spy (2020) dir. Kiyoshi Kurosawa

#lust caution#wife of a spy#ang lee#kiyoshi kurosawa#2000s#2020s#china#taiwan#hong kong#japan#usa#espionage#war#romance#thriller#double bill suggestions

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

“This is not an all-out war but a decentralized one with seemingly unconnected fronts that span across continents. It is fought in a hybrid style, meaning both with tanks and planes and with disinformation campaigns, political interference, and cyberwarfare. The strategy blurs the lines between war and peace and combatants and civilians. It puts a lot of extra fog in the "fog of war."

China, Russia, and Iran disagree on many things, but they all have the same goal: ridding their regions of U.S. influence and creating a multipolar global governance system and Tehran, Beijing, and Moscow know that U.S. political and military might is the only force preventing them from imposing their will on their neighbors.

(…)

When it comes to this war, the United States is asleep at the wheel. U.S. strategy has been about preparation for a large conventional war, containment, and weak deterrence. Washington has been pitifully absent in the irregular warfare field. There are almost no punishments or accountability—besides ineffective sanctions—for the nations that attack us.

(…)

Should the Biden administration continue its ineffective course, these countries will only be emboldened. Should support for Israel or Ukraine fail, China will be more likely to invade Taiwan. Deterrence is a great strategy but only works when the other side believes you will carry out your threats. You must establish that understanding by holding your enemies accountable for moves they take against you.

(…)

The Biden administration's support for Ukraine has been a rare show of force that has sent a strong message to the world. But it isn't enough. The U.S. foreign policy establishment must recognize the hybrid war being waged against it and show up on the irregular field of battle. Like it or not, the United States is the guarantor of stability in the world. By retreating from its responsibilities, the only thing Washington is guaranteeing is dark times ahead.”

“The list encompasses not just the wars in Gaza and Ukraine, but hostilities between Armenia and Azerbaijan in Nagorno-Karabakh, Serbian military measures against Kosovo, fighting in Eastern Congo, complete turmoil in Sudan since April, and a fragile cease-fire in Tigray that Ethiopia seems poised to break at any time. Syria and Yemen have not exactly been quiet during this period, and gangs and cartels continuously menace governments, including those in Haiti and Mexico. All of this comes on top of the prospect of a major war breaking out in East Asia, such as by China invading the island of Taiwan.

The Uppsala Conflict Data Program, which has been tracking wars globally since 1945, identified 2022 and 2023 as the most conflictual years in the world since the end of the Cold War. Back in January 2023, before many of the above conflicts erupted, United Nations Deputy Secretary-General Amina J. Mohammed sounded the alarm, noting that peace “is now under grave threat” across the globe. The seeming cascade of conflict gives rise to one obvious question: Why?

(…)

The first explanation holds that the cascade is in the eye of the beholder. People are too easily “fooled by randomness,” the essayist and statistician Nassim Nicholas Taleb admonished in his 2001 book of the same title, seeking intentional explanations for what may be coincidence. The flurry of armed confrontations could be just such a phenomenon, concealing no deeper meaning: Some of the frozen conflicts, for instance, were due for flare-ups or had gone quiet only recently. Today’s volume of wars, in other words, should be viewed as little more than a series of unfortunate events that could recur or worsen at any time.

(…)

Although coincidences certainly do occur, the current onslaught happens to be taking place at a time of big changes in the international system. The era of Pax Americana appears to be over, and the United States is no longer poised to police the world. Not that Pax Americana was necessarily so peaceful. The 1990s were especially disputatious; civil wars arose on multiple continents, as did major wars in Europe and Africa. But the United States attempted to solve and contain many potential conflicts: Washington led a coalition to oust Saddam Hussein’s Iraq from Kuwait, facilitated the Oslo Process to resolve the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, fostered improved relations between North and South Korea, and encouraged the growth of peacekeeping operations around the globe. Even following the 9/11 terrorist attacks on the United States, the invasion of Afghanistan was supported by many in the international community as necessary to remove a pariah regime and enable a long-troubled nation to rebuild. War was not over, but humanity seemed closer than ever to finding a formula for lasting peace.

Over the subsequent decades, the United States seemed to fritter away both the goodwill needed to support such efforts and the means to carry them out. By the early 2010s, the United States was bogged down in two losing wars and recovering from a financial crisis. The world, too, had changed, with power ebbing from Washington’s singular pole to multiple emerging powers. As then–Secretary of State John Kerry remarked in a 2013 interview in The Atlantic, “We live in a world more like the 18th and 19th centuries.” And a multipolar world, where several great powers jostle for advantage on the global stage, harbors the potential for more conflicts, large and small.

Specifically, China has emerged as a great power seeking to influence the international system, whether by leveraging the economic allure of its Belt and Road Initiative or by militarily revising the status quo within its region. Russia does not have China’s economic muscle, but it, too, seeks to dominate its region, establish itself as an influential global player, and revise the international order. Whether Russia or China is yet on an economic or military par with the United States hardly matters. Both are strong enough to challenge the U.S.-led international order by leveraging the revisionist sentiment they share with countries throughout the global South.

(…)

Suppose, though, that the proliferation of wars doesn’t have a systemic cause, but an entirely particular one. That the world owes its present state of unrest directly to Russia—and, even more specifically, to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February of 2022 and its decision to continue fighting since.

The war in Ukraine, the largest war in Europe since World War II and one poised to continue well past 2024, is absorbing the attention of international actors who otherwise would have been well positioned to prevent any of the abovementioned crises from escalating. This case is not the same as the great-power distraction, in which the world’s most powerful states simply fail to focus on emerging crises. Rather, the great powers lack the diplomatic and military capacity to respond to conflicts beyond Ukraine—and other actors know it.

(…)

These three explanations—coincidence, multipolarity, Russia’s war in Ukraine—are not mutually exclusive. If anything, they are interrelated, as wars are complex events; the decline of U.S. hegemony contributes to growing multipolarity; and great-power competition has surely fed Russia’s aggression and the West’s response. The consequence is that others are caught in the great-power cross fire or will seek to start fires of their own. Even if none of these wars rise to the level of a third world war, they will be devastating all the same. We do not need to be in a world war to be in a world at war.

Wars were already a persistent feature of the international system. But they were not widespread. War was always happening somewhere, in other words, but war was not happening everywhere. The above dynamics could change that tendency. The prevalence of war, not just its persistence, could now be our future.”

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

Almost Nothing Is Worth a War Between the U.S. 🇺🇸 and China 🇨🇳

Americans and Chinese have to rehumanize each other in terms of the way we conceive of our problems and engage.

— By Howard W. French | Foreign Policy | August 21, 2023

A child sitting on a man's shoulder takes a picture as she visits the Bund waterfront area in Shanghai, China, on July 5, 2023. Wang Zhao/AFP Via Getty Images

Midway into my just-completed one-month stay in China, I found myself seated alone in a tasteful restaurant in an upscale shopping mall in Shanghai, where I had gone for dinner.

There, amid dim lighting and soft traditional music, I had a kind of revelation. Bear with me. Against the opposite wall sat a three-generation Chinese family dining together. Two grandparents, slouching a bit, their visages deeply lined, faced in my direction, and seemed to exhibit mild curiosity about what has become a rare sighting recently, even in China’s most cosmopolitan city: a foreigner. They watched closely as I spoke with the waiter in Chinese to complete my order.

Two other people—from all evidence their much taller daughter, who was dressed in the refined way of a well-paid professional, and a small grandchild—sat with their backs to me. I was only able to see their faces when the mother stood up mid-meal to take her girl to the bathroom. In this little glimpse of three generations, an entire world opened up for me, as did a deep sense of alarm over one of the most urgent problems facing all of humanity in these times.

As a former longtime resident of China and someone who has been studying the country since I was a college student many decades ago, I could not prevent myself from trying to imagine the run of experiences the two elders had lived through. I guessed they were roughly my age, meaning in their 60s, but they looked a lot older and more worn than your average well-kept American of similar age.

This meant they would probably have harsh memories of the Cultural Revolution, the decade of political violence and upheaval that began under Mao Zedong in 1966. They or their families may also have suffered even worse tribulations late in the previous decade during the “Great Leap Forward,” when Mao’s crash effort to industrialize resulted in tens of millions of Chinese people starving to death.

Now, the elderly looking man who gazed across the narrow space separating us wore a light blue Gap t-shirt as he picked his way gingerly through a three-course meal, seemingly taking his time to chew. What did he understand of the symbolism of mass consumerism represented in the white logo emblazoned on his shirt? What did he make of the proliferation of this temple of marketing and surplus that is the shopping mall, a cultural phenomenon that contemporary China has made its own? How did he feel about the long curve of his life? Of the grave errors that China had made, but also about where it had ended up, or at least where it stood in this moment? I almost wanted to ask him, but thinking it would have been too much of an intrusion, I restrained myself, with regret.

In those moments, these thoughts impelled me to think about the curve of life in my own country, the United States, too—of how easily one can assume a kind of superior or even triumphalist attitude toward other people in other places. I had just missed being of draft age in the Vietnam War, a senseless tragedy visited upon tens of millions of Southeast Asians, for reasons as specious as many of Mao’s economic and political ideas. I thought of the persistent denial of civil rights for African Americans, which continued in a de jure sense almost into my teenage years. I thought of the devastation to the planet caused by America’s heedless crusade for wealth. Then, based on the evidence, I concluded that bad decisions and human folly are, well, universally human.

The biggest human folly I can presently think of, though, would be something that nowadays seems frighteningly easy to imagine: a war between the United States and China. Until the coronavirus pandemic, I had either lived in or visited China every year since the late 1990s. I plan to write several columns based on my recent return to the country after four years of pandemic-enforced absence. But this is not yet the occasion for a deep exploration for the political, economic, and strategic issues that are pushing to the two countries so far apart and fueling ever greater risk of catastrophe.

I’ll just say here that this is not a situation where, as so many in each country may be inclined to think, if only the other side would stop doing things that threaten or provoke us, the war clouds would dissipate. We have problems together, and if they are to be prevented from causing mass death and destruction, both countries will have to escape the endless loop of reflexively problematizing and sometimes essentializing the other, along with the relentless self-justification.

Many will think me naive, but this has to begin with something all too rare. Americans and Chinese have to rehumanize each other in terms of the way we conceive of our problems and engage. Actually, seeing people in China, like that family across from me at dinner, helped bring this home. But how can this be achieved for the crushing majority of Americans and Chinese who will never visit the other’s country? How can we strip off the layers of surface things that separate us to get in touch with the profound humanity that should unite us? It’s hard work, and the answer is not obvious, but it is urgent.

Since I’m ready to be accused of naivete, I’ll try to start first. There is almost nothing that is worth a war between the United States and China. I’ll come back to the tricky sounding “almost” in a second—it’s actually not as big of an asterisk as some might imagine. Control over Taiwan, which the government of Chinese President Xi Jinping has made into an all-too-public obsession, is not worth the killing that would be unleashed by a Chinese invasion and by any U.S. response in defense of that island. Continued U.S. geopolitical preeminence in the world is also not worth a major armed conflict with China. This is not a call for capitulation, but rather for both countries to find ways to prioritize coexistence and avoid disaster.

As a non-academic historian, I read an inordinate amount about the past, and I have always been struck by the airs of overconfidence and intoxication that have preceded many great past conflicts. On the eve of World War I, for example, elites on both sides—in Germany and Britain—were blithely predicting the troops would be home by Christmas.

Most Americans (and most Chinese) probably spend precious little time thinking about what war would do to their own country. It would be useful to give a wider airing of war game scenarios, such as one carried out recently by the Center for Strategic and International Studies, that make clear just how devastating a conflict could be. In this example, just one of many, Hawaii, Guam, Alaska, and San Diego, California, would all come under withering Chinese attack, up to and potentially including with nuclear weapons. Lest Chinese people think that they would have little to fear by way of direct impact, just for starters, many areas of coastal China, where the country’s population and wealth are heavily concentrated, could face a rain of U.S. missiles.

What are people willing to concede in order to avoid such a fate? In a book I wrote about China’s conception of itself as a great power, I concluded that the United States needed, for starters, to signal a lot more serenity in its competition with China. For at least two decades, my country has behaved as if a bit haunted by the prospect of being overtaken. But for objective reasons—including China’s extraordinarily profound demographic problems, the declining effectiveness of China’s economic policies, and a plethora of domestic challenges in the country—the United States needn’t be. What is more, though, is that the signals of American anxiety, which are rife in the political culture and come through in many U.S. policies, fuel Chinese nervousness, insecurity, and over-assertiveness.

China, for its part, needs to get over its own insecurities. The air of self-confidence it seeks to project is powerfully belied by the constant resort to overt nationalism and to assertions that in its dealings with other countries—or with international bodies like international tribunals governing laws of the sea, for example—only others are capable of incorrect positions. China, by contrast, is not only always right but also righteous.

Beijing is profoundly worried about the staying power of its own political system, but it needn’t obsess, as it claims to, over the supposed efforts of others to undermine it. Whatever threats there are to China’s system of rule come from within China itself. Nobody outside of the country, in other words, is trying to bring down the Communist Party. Only the party itself can achieve this, by failing to reform in step with the desires of the country’s own population.

So how can we restore some confidence on both sides? First the asterisk from above. War should be ruled out except in the case of a direct attack by one side on the other, which means we should rule out attacking each other. China should meanwhile also lower the temperature on Taiwan, in tandem with more reassurances from the United States that Washington does not support the idea of formal independence for the island.

Chinese and American leaders also have to start speaking with each other and meeting much more often face to face. There is really no substitute for this, for as much as what were once called people-to-people exchanges can reinforce a shared sense of humanity, seeing political leaders shake hands and smile and meet across the table to discuss thorny issues separating the two sides can also remind both countries’ public and political classes that there is nothing so hard that it can’t be talked about.

— Howard W. French is a Columnist at Foreign Policy, a Professor at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, and a longtime Foreign Correspondent. His latest book is Born in Blackness: Africa, Africans and the Making of the Modern World, 1471 to the Second World War.

#Foreign Policy#China 🇨🇳 | United States 🇺🇸#Worthless War#Howard W. French#Argument#Cultural Revolution#Vietnam War#Mao’s Economic and Political Ideas#Political | Economic | Strategic Issues#Taiwan 🇹🇼#Hawaii | Guam 🇬🇺 | Alaska | San Diego#Beijing | Washington

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

In 1949, General Chiang Kai-shek moved his Nationalist Party, the Kuomintang (KMT), to the island and established the Republic of China there. Ever since, the People’s Republic of China has seen Taiwan as its ideological enemy, an irritating reminder that not all Chinese wish to be united under the leadership of the Communist Party.

Sometimes Chinese pressure on Taiwan has been military, involving the issuing of threats or the launching of missiles. But in recent years, China has combined those threats and missiles with other forms of pressure, escalating what the Taiwanese call “cognitive warfare”: not just propaganda but an attempt to create a mindset of surrender. This combined military, economic, political, and information attack should by now be familiar, because we have just watched it play out in Eastern Europe. Before 2014, Russia had hoped to conquer Ukraine without firing a shot, simply by convincing Ukrainians that their state was too corrupt and incompetent to survive. Now it is Beijing that seeks conquest without a full-scale military operation, in this case by convincing the Taiwanese that their democracy is fatally flawed, that their allies will desert them, that there is no such thing as a “Taiwanese” identity.

Taiwanese government officials and civic leaders are well aware that Ukraine is a precedent in a variety of ways. During a recent trip to Taiwan’s capital, Taipei, I was told again and again that the Russian invasion of Ukraine was a harbinger, a warning. Although Taiwan and Ukraine have no geographic, cultural, or historical links, the two countries are now connected by the power of analogy. Taiwanese Foreign Minister Joseph Wu told me that the Russian invasion of Ukraine makes people in Taiwan and around the world think, “Wow, an authoritarian is initiating a war against a peace-loving country; could there be another one? And when they look around, they see Taiwan.”

But there is another similarity. So powerful were the Russian narratives about Ukraine that many in Europe and America believed them. Russia’s depiction of Ukraine as a divided nation of uncertain loyalties convinced many, prior to February, that Ukrainians would not fight back. Chinese propaganda narratives about Taiwan are also powerful, and Chinese influence on the island is both very real and very divisive. Most people on the island speak Mandarin, the dominant language in the People’s Republic, and many still have ties of family, business, and cultural nostalgia to the mainland, however much they reject the Communist Party. But just as Western observers failed to understand how seriously the Ukrainians were preparing—psychologically as well as militarily—to defend themselves, we haven’t been watching as Taiwan has begun to change too.

Although the Taiwanese are regularly said to be too complacent, too closely connected to the People’s Republic, not all Taiwanese even have any personal links to the mainland. Many descend from families that arrived on the island long before 1949, and speak languages other than Mandarin. More to the point, large numbers of Taiwanese, whatever their background, feel no more nostalgia for mainland China than Ukrainians feel for the Soviet Union. The KMT’s main political opponent, the Democratic Progressive Party, is now the usual political home for those who don’t identify as anything except Taiwanese. But whether they are KMT or DPP supporters (the Taiwanese say “blue” or “green”), whether they participate in angry online debates or energetic rallies, the overwhelming majority now oppose the old “one country, two systems” proposal for reunification. Especially since the repression of the Hong Kong democracy demonstrations, millions of the island’s inhabitants understand that the Chinese war on their society is not something that might happen in the future but is something that is already well under way.

Like the Ukrainians, the Taiwanese now find themselves on the front line of the conflict between democracy and autocracy. They, too, are being forced to invent strategies of resistance. What happens there will eventually happen elsewhere: China’s leaders are already seeking to expand their influence around the world, including inside democracies. The tactics that the Taiwanese are developing to fight Chinese cognitive warfare, economic pressure, and political manipulation will eventually be needed in other countries too.

— China’s War Against Taiwan Has Already Started

#anne applebaum#china's war against taiwan has already started#history#current events#military history#politics#taiwanese politics#chinese politics#communism#propaganda#psychological warfare#culture#identity#chinese civil war#china#taiwan#republic of china#hong kong#chiang kai-shek#kuomintang#democratic progressive party

25 notes

·

View notes

Text

For anyone honestly still asking why the US or other countries should support Ukraine against Russia, here's why:

When Ukraine became an independent country upon the breakup of the Soviet Union, it, along with Belarus and Kazakhstan, signed the Budapest Memorandum, an agreement with Russia, the US, and the UK where it gave up the immense stockpile of Soviet nuclear weapons it retained (then the third-largest nuclear arsenal in the world), and signed the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, on the condition that, among other things, the other signatories, including Russia, would respect it's sovereignty and borders. It is facing the threat of annihilation now because this agreement has not been upheld.

2. Any "peace" achieved by the surrender of Ukraine's land and people to Russian occupation and genocide would be an illusory and temporary one. Not only for the subjugated and brutalized people of Ukraine, who would no more know peace than any other people under authoritarian rule, but for the world. Every nation with expansionist aims would see Russia's victory as proof that they too could get away with annexing weaker countries' territory by force. This has not been the norm for nearly a century (for all the criticisms of the US invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, the US never tried to outright annex either country's territory into the US). What we are talking about is a return to the days of colonial "Great Powers"- a world order which gave us two world wars in less than thirty years before we finally put an end to it.

Such a "peace" would be soon interrupted, likely either by a Chinese invasion of Taiwan, or by Russia moving on to it's next target once it had sufficiently rebuilt it's strength- either scenario being one with a high risk of leading to global nuclear war.

#Ukraine#Russia#China#Taiwan#Appeasement#Genocide#Imperialism#Colonialsim#Nuclear War#World War#Budapest Memorandum#Slava Ukrainii

4 notes

·

View notes