#chinese literature

Text

Welcome to The Journey to the West (西游记) Daily!

You are about to beging a reading journey to get the hidden Buddhist texts accompanied by the monk Tang Sanzang, Sun Wukong, Sha Wujing, Zhu Bajie and Bai Long Ma.

To beging this journey you must subscribe to the newsletter, which you will find at https://journeytothewestdaily.substack.com/. You wil receive your first email this week, welcoming you and sharing information about what's to come and what I will include in the emails.

However, beforehand I want to tell you already that you won't receive a daily email, despite the name of the newsletter. The chapters are dense and full of references to folklore or religion references that you might be unfamiliar with, so you will receive an email every 2 or 3 days maximum.

If this is the first time that you hear about this newsletter and you don't know what Journey to the West is...

The classical Chinese novel Journey to the West is an extended account of the legendary pilgrimage of the Tang dynasty Buddhist monk Xuanzang, who traveled to the "Western Regions" (Central Asia and India) to obtain Buddhist sūtras (sacred texts) and returned after many trials and much suffering. Gautama Buddha gives this task to the monk, whose name in the novel is Tang Sanzang, and provides him with three protectors who agree to help him as an atonement for their sins. These disciples are the Monkey King, Zhu Bajie, and Sha Wujing, together with a dragon prince who acts as the monk's steed, a white horse. The group of pilgrims journey towards enlightenment by the power and virtue of cooperation.

The novel is perfect for the epistolary format, since it's is divided in different and disconnected adventures, so you don't have to always remember what happened in the previous chapter to read the next!

We'll be reading Anthony C. Yu's translation since it is the first unabridged version that we have available in English. It is about 100 chapters long.

As I said, you will receive a first email as soon as you subscribe and an introductory email in a few days. Please, share this post so more people can read along. Use the hashtag #jttwdaily if you want to comment your impressions. I'll share the most important dates soon.

May the Buddha help you in your endeavours.

#journey to the west#journey to the West daily#jttwdaily#西游记#Dracula daily#chinese literature#classical Chinese literature#cdrama#the untamed

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

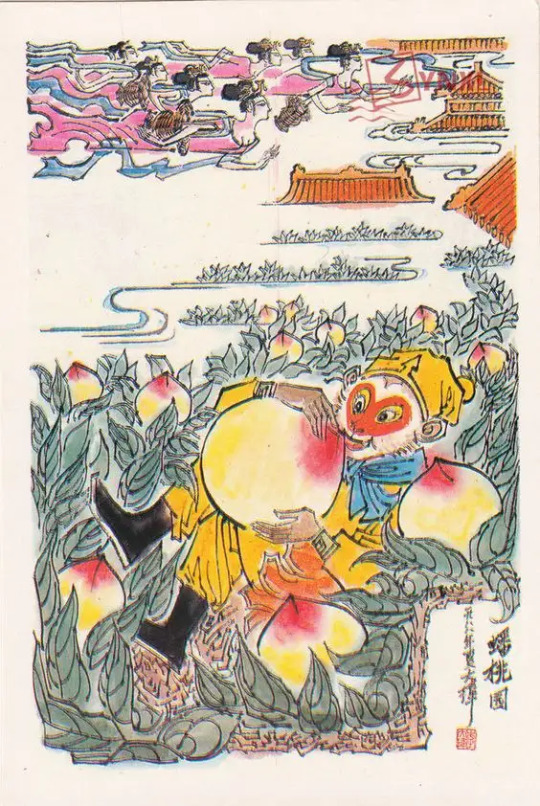

Dragon Kings of the Four Seas

Renowned Shanghai painter’s Dai Dunbang (戴敦邦) 20th century illustration for the Chinese Ming dynasty classic “Journey to the West” (《西遊記》) attributed to Wu Cheng'en (吳承恩).

#chinese art#ancient china#chinese culture#chinese painting#chinese calligraphy#chinese ink#ink painting#watercolor#dragon#dragon art#mythical creatures#chinese mythology#mythological creatures#journey to the west#chinese literature#dragon king#Dai Dunbang#西遊記

755 notes

·

View notes

Text

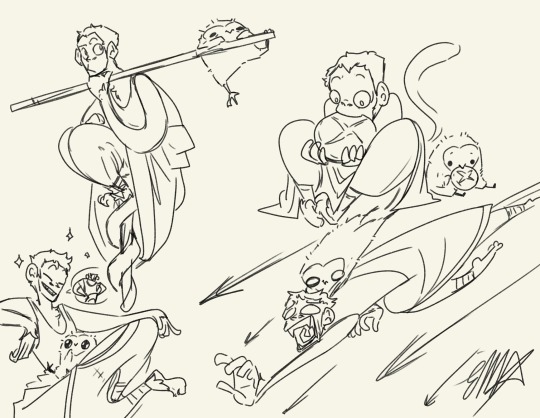

Intermediate Character design class project: animals

It’s just the monkey king

#digital art#drawing#illustration#fanart#artists on tumblr#fantasy#art#web comic#monkey#monkey king#son wukong#journey to the west#chinese mythology#oc#chinese literature#owl#barn owl#owlet

257 notes

·

View notes

Text

"You know what I think? I think this whole concept of women being docile and obedient is nothing but wishful thinking. Or why would you put so much effort into lying to us? Into crippling our bodies? Into coercing us with made-up morals you claim are sacred? You insecure men, you're afraid. You can force us into compliance, but, deep down, you know you can't force us to truly love and respect you. And without love and respect, there will always be a seed of hatred and resistance. Growing. Festering. Waiting."

Xiran Jay Zhao, Iron Widow

#Xiran Jay Zhao#Iron Widow#female rage#rage#resistance#International Women's Day#women#Chinese literature#BIPOC author#quotes#quotes blog#literary quotes#literature quotes#literature#book quotes#books#words#text

165 notes

·

View notes

Note

I've heard the idea that Monkey is 7 times immortal thrown around a couple times, but my count has only ever gone up to 4 (the peaches, the pills, the wine, and his daoist studies). How immortal IS Monkey?

I count at least six levels of immortality.

1) Daoist Longevity Arts - Ch. 2

I discuss the exact methods here.

A photomanipulation by me.

2) Erasing Allotted Lifespan - Ch. 3

[After Monkey is summoned to hell in his sleep and thereafter threatens to beat the Judges of Hell for their mistake] The Ten Kings immediately had the judge in charge of the records bring out his [Sun's] books for examination. The judge, who did not dare tarry, hastened into a side room and brought out five or six books of documents and the ledgers on the tens species of living beings ... He [Monkey] had, therefore, a separate ledger, which Wukong examined himself. Under the heading "Soul 1350" he found the name Sun Wukong recorded, with the description: "Heaven-born Stone Monkey. Age: three hundred and forty-two years. A good end."

Wukong said, "I really don't remember my age. All I want is to erase my name. Bring me a brush." The judge hurriedly fetched the brush and soaked it in heavy ink. Wukong took the ledger on monkeys and crossed out all the names he could find in it. Throwing down the ledger, he said, "That ends the account! That ends the account! Now I'm truly not your subject" (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, pp. 140-141).

A print from the Japanese children book Son Goku (1939).

3) Immortal Peaches - Ch. 5

[After being appointed the guardian of the Queen Mother of the West's immortal peach groves] The Great Sage ... asked the local spirit, "How many trees are there?" "There are three thousand six hundred," said the local spirit. "In the front are one thousand two hundred trees with little flowers and small fruits. These ripen once every three thousand years, and after one taste of them a man will become an immortal enlightened in the Way, with healthy limbs and a lightweight body. In the middle are one thousand two hundred trees of layered flowers and sweet fruits. They ripen once every six thousand years. If a man eats them, he will ascend to Heaven with the mist and never grow old. At the back are one thousand two hundred trees with fruits of purple veins and pale yellow pits. These ripen once every nine thousand years and, if eaten, will make a man's age equal to that of Heaven and Earth, the sun and the moon..."

One day he [Monkey] saw that more than half of the peaches on the branches of the older trees had ripened, and he wanted very much to eat one and sample its novel taste. Closely followed, however, by the local spirit of the garden, the stewards, and the divine attendants of the Equal to Heaven Residence, he found it inconvenient to do so. He therefore devised a plan on the spur of the moment and said to them, "Why don't you all wait for me outside and let me rest a while in this arbor?" The various immortals withdrew accordingly. That Monkey King then took off his cap and robe and climbed up into a big tree. He selected the large peaches that were thoroughly ripened and, plucking many of them, ate to his heart's content right on the branches. Only after he had his fill did he jump down from the tree. Pinning back his cap and donning his robe, he called for his train of followers to return to the residence. After two or three days, he used the same device to steal peaches to gratify himself once again

One day the Lady Queen Mother decided to open wide her treasure chamber and to give a banquet for the Grand Festival of Immortal Peaches, which was to be held in the Palace of the Jasper Pool. She ordered the various Immortal Maidens ... to go with their flower baskets to the Garden of Immortal Peaches and pick the fruits for the festival ... [After meeting with the Great Sage's ministers] The local spirit went into the garden with them; they found their way to the arbor but saw no one. Only the cap and the robe were left in the arbor, but there was no person to be seen. The Great Sage, you see, had played for a while and eaten a number of peaches. He had then changed himself into a figure only two inches high and, perching on the branch of a large tree, had fallen asleep under the cover of thick leaves (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, pp. 161-162).

A new years print found online.

4) Immortal Wine - Ch. 5

Our Great Sage could not make an end of staring at the scene [the heavenly feast set for the Immortal Peach Banquet] when he suddenly felt the overpowering aroma of wine ... standing beside the jars and leaning on the barrels, he abandoned himself to drinking. After feasting for a long, he became thoroughly drunk...

[...]

[After returning to Flower Fruit Mountain and meeting with his children, he says] "When I was enjoying myself this morning at the Jasper Pool, I saw many jars and jugs in the corridor full of the juices of jade [yuye qiongjiang, 玉液瓊漿; lit: "Jade liquid and jade syrup"], which you have never savored. Let me go back [to heaven] and steal a few bottles to bring down here. Just drink half a cup, and each of you will live longer without growing old" ... He took two large bottles, one under each arm, and carried two more in his hands. Reversing the direction of his cloud, he returned to the monkeys in the cave. They held their own Festival of Immortal Wine [Xianjiu hui, 仙酒會], with each one drinking a few cups" (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, pp. 165 and 167).

A screenshot from the 1986 Journey to the West TV show.

5) Immortal Elixir - Ch. 5

[After Sun Wukong drunkenly stumbles into Laozi's laboratory in the Tushita Heaven] He found no one but saw fire burning in an oven beside the hearth, and around the oven were five gourds in which finished elixir was stored. "This thing is the greatest treasure of immortals," said the Great Sage happily. "Since old Monkey has understood the Way and comprehended the mystery of the Internal's identity with the External, I have also wanted to produce some golden elixir on my own to benefit people. While I have been too busy at other times even to think about going home to enjoy myself, good fortune has met me at the door today and presented me with this! As long as Laozi is not around, I'll take a few tablets and try the taste of something new." He poured out the contents of all the gourds and ate them like fried beans (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, p. 166).

A detail from the 1835 Japanese translation of Journey to the West.

6) Ginseng Tree Fruit - Ch. 24

In the mountain there was a Daoist Abbey called the Five Villages Abbey [Wu zhuang guan, 五莊觀]; it was the abode of an immortal whose Daoist style [name] was Master Shenyuan [Shenyuan zi, 鎮元子] and whose nickname was Lord, Equal to Earth [Shi tong jun, 世同君]. There was, moreover, a strange treasure grown in this temple, a spiritual root that was formed just after chaos had been parted and the nebula had been established prior to the division of Heave and Earth. Throughout the four great continents of the world, it could be found in only the Five Villages Abbey in the West Aparagodaniya Continent. This treasure was called grass of the reverted cinnabar [cao huan dan, 草還丹], or the ginseng fruit [renshen guo, 人參果]. It took three thousand years for the plant to bloom, another three thousand years to bear fruit, and still another three thousand years before they ripened. All in all, it would be nearly ten thousand years before they could be eaten, and even after such a long time, there would be only thirty such fruits. The shape of the fruit was exactly that of a newborn infant not yet three days old, complete with the four limbs and the five senses. If a man had the good fortune of even smelling the fruit, he would live for three hundred and sixty years; if he ate one he would reach his forty-seven thousandth year.

[After Wukong learns the complicated method of harvesting the fruit] Parting the leaves and branches, he knocked three of the fruits into the sack ... The three of them [Monkey and his brothers] took the fruits and began to enjoy them (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 1, pp. 453 and 462-463).

Monkey holding ginseng tree fruit. Image found online.

This previous article talks about the history of this magical fruit.

An important note

Sun Wukong is not really immortal, just long-lived and hard to kill. Immortality in Ming to Qing-era popular literature means that you can live for a long time but still die if injured badly enough. Think of it like an infinitely long candle being blown out instead of having a chance to burn for centuries or eons. For example, Investiture of the Gods (Fengshen yanyi, 封神演義, c. 1620), a sort of prequel to Journey to the West, is full of immortals killed in battle with heavenly weapons. Some even have their immortality sapped away before dying in one of many celestial traps. The biggest of these traps is the "Ten Thousand Immortal Array" (Wanxian zhen, 萬仙陣), so named because it can apparently kill myriad transcendents.

I commonly suggest that Monkey's levels of immortality just make him more durable than your average celestial.

Source:

Wu, C., & Yu, A. C. (2012). The Journey to the West (Vols. 1-4) (Rev. ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press.

#sun wukong#monkey king#journey to the west#Chinese immortal#immortality#Chinese literature#Daoism#Taoism#Buddhism#fengshen yanyi#elixir#lego monkie kid#LMK

149 notes

·

View notes

Text

So I found this on Weibo and I couldn't stop laughing. This is incredibly niche but I feel the need to share and explain this to my friends on this side.

So the bottom half is the photos that we initially thought were the royal suitor photos before the movie came out, then realized it was in the texting montage, then confirmed by Matthew that this actually isn't Alex and Henry, it was Taylor and Nick chilling between takes.

NOW, the photo on top is a still from 1987 TV show adaptation of one of the four Chinese Classics: "The Dream of the Red Chamber". That is the main couple reading another classical Chinese novel (yes this is very meta) "Romance of the Western Chamber" together, and I think this book that they're reading is the first romance novel/love story to have the couple be in starkly different social standings yet be together in the end.

This isn't a case of parallel in the same sense as my posts putting firstprince and Rapunzel x Eugene or Simba x Nala or Jack x Rose together and finding similarities. In fact, the couple from Red Chamber is nothing like firstprince or Taylor and Nick, not even remotely close, and their relationship ended in tragedy: spoilers, the girl died of a broken heart and the boy lost the will to live and became a monk.

But the point here is that this pair? This is our culture's Romeo and Juliet, our Pyramus and Thisbe. This scene in particular, this imagery of them reading in the garden together, has the same significance as the balcony scene in Romeo and Juliet. Like, if you ask a Chinese person for an imagery from classical literature that depicts love, this is the image most people will say.

AND SOMEHOW THIS PHOTO OF TAYLOR AND NICK THAT WE ALL THOUGHT WAS ALEX AND HENRY LOOKS EXACTLY THE SAME AS IT

This is the most random connection and it's definitely a stretch but as someone who cried over the ship in the top half at the age of 11 I am so fucking amused by this comparison

#rwrb#red white and royal blue#rwrb movie#taylor zakhar perez#alex claremont diaz#nicholas galitzine#henry fox mountchristen windsor#henry hanover stuart fox#firstprince#dream of the red chamber#jia baoyu#lin daiyu#also the boy and the girl are technically cousins but we don't talk about that#rwrb parallels#taynick? I don't know what this counts as anymore#rwrb rambles#again this is purely self indulgent#meraki translates#but I find joy in sharing things of my culture that i approve of#and translating is fun#the dream of the red chambers is the most complex out of the four Chinese classics#it has the most literature scholars studying it#also we technically have two sets of tragic lover they're one of them#the other one basically is beat for beat romeo and juliet#and they die and turn into butterflies#anyways i'm done rambling for this#chinese literature

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Nine-headed hermit": the early history of Zhong Kui (and his sister)

Gong Kai's painting Zhongshan Going on Excursion, showing Zhong Kui, his sister and various demons during a journey (wikimedia commons)

Zhong Kui is probably one of the most recognizable figures from Chinese mythology today and continues to star in novels, movies and other works. However, his modern image largely depends on sources the Ming and Qing periods. In this article, I’ll attempt to instead shed some light on some lesser known aspects of his earlier history. You will be able to learn why he was called a “nine headed hermit” despite having only one head, what he had to do with foxes, when his sister was portrayed as an exorcist like him, and more. As a bonus, I’ve included a brief summary of Zhong Kui’s reception in medieval Japan.

The earliest history of Zhong Kui

Zhong Kui’s history goes all the way back to the Zhou period (most of the first millennium BCE). A homophone of his name (鍾馗), zhongkui (終葵; also zhongzui, 終椎) at the time referred to a type of ritual mallet used to expel demons. During the Six Dynasties period first cases of this term (now written as 鍾馗 ori 鍾葵) being used as a personal name start to pop up. The purpose was most likely to confer the protection granted by such objects to a child just through their name. Numerous cases are attested, and it doesn’t seem the bearers of the moniker Zhong Kui can be distinguished by a specific origin, social class or even gender.

The earliest possible reference to a specific supernatural being named Zhong Kui comes from the Taishang Dongyuan Shenzhou Jing (太上洞淵神咒經; “Scripture of the Divine Incantations of the Abyssal Caverns of the Most High”), a Daoist work possibly composed as early as in the fourth century. The oldest surviving copy of the passage concerning Zhong Kui has been identified in a copy from Dunhuang dated to 664. He appears in it as an assistant of king Wu of Zhou and Confucius (sic) who helps them subjugate ghosts and disease demons.

It is not impossible that to the compilers of Taishang Dongyuan Shenzhou Jing Zhong Kui was only a stand-in for an exorcist, though, not a single well defined figure. There’s an eyewitness account of such specialists dressing up in leopard skins, painting their faces red and announcing they are Zhong Kui in another, slightly newer Dunhuang text. It specifies that many Zhong Kui exist, and that they answer to the “General of Five Paths”, an originally apocryphal Buddhist figure eventually canonized as one of the kings of hell (you can find an excellent article about him here).

In any case, regardless of the clear evidence for ambiguous use of the term in earlier times, it is agreed Zhong Kui became a well defined figure by the end of the Tang period. That’s also when legends about his origin started to circulate.

The legend of Zhong Kui

A typical depiction of Zhong Kui as a Tang period official by the Qing period artist Lü Xue (wikimedia commons)

According to the most popular version of Zhong Kui’s origin story, he was a scholar from the Zhongnan Mountains who lived during the reign of Gaozu of Tang (reigned 618-626). He took part either in the imperial examination or the imperial military examination (that’s an ahistorical detail - it was established by Wu Zetian in 702), but failed.

This detail is not elaborated upon further in early accounts, but by the Ming period it was attributed not to lack of skill but rather to prejudice against Zhong Kui’s physical appearance (he is fairly consistently described as dark-skinned, unusually tall, with a bulbous head and excessive facial hair). It’s possible that this new backstory was based in part on experiences of real officials of foreign origin, whose appearance was sometimes mocked by their peers, as already documented in Tang sources. Another possibility is that the descriptions were meant to be exaggerated to the point of making him resemble a demon, though.

Either way, out of despair caused by failure Zjong Kui committed suicide by smashing his head against the steps leading to the imperial palace. However, since in his final words he swore to protect the emperor and his realm, he didn’t return as a vengeful ghost, but rather as a queller of malevolent supernatural entities. Alternatively, he took this role out of gratitude for Gaozu, who was saddened by his death and organized the burial worthy of an honored official for him. Note that in later plays which often serve as the basis for modern adaptations, the burial is typically arranged by a certain Du Ping (杜平), a friend of Zhong Kui from back home.

Apparently a version in which the kings of hell are so impressed by Zhong Kui that they decide to make him the king of the ghosts also exists, though I was unable to track down its original source. In any case, he is associated with Mount Fengdu - one of the terms referring to the realm of the dead - in a poem by Song Wu (宋无; 1260–1340) already. He, or at least generic clerk figures based on his iconography, also sometimes appear in Song period paintings of the Ten Kings.

Several Zhong Kui-like clerks from a depiction of hell in Sermon on Mani's Teaching of Salvation (wikimedia commons)

According to Shih-shan Huang a single example of such a figure has even been identified in a Manichaean context, specifically in the scroll Sermon on Mani’s Teaching on Salvation.

Manichaean curiosities aside, supposedly the first person to be aided by Zhong Kui was emperor Xuanzong of Tang. At some point he fell gravely ill. In a dream, he saw a demon who attempted to steal a flute which was one of his most prized possessions. However, the attempt was foiled by a fearsome giant, who dealt with the thief rather brutally, poking out one of his eyes and then devouring him. After completing this act of demon quelling, he explained that he is Zhong Kui, and how he came to fulfill his current role.

After waking up, Xuanzong felt healthy again. He was so impressed he commissioned Wu Daozi, arguably the most famous artist in China at the time, to prepare a painting of Zhong Kui which could be used as a talisman against any further supernatural issues. Supposedly it left quite the impression on the general populace, and soon numerous images of Zhong Kui started to be distributed as talismans. There is definitely a kernel of truth to this part of the legend, as eyewitness accounts of Wu Daozi’s painting exist, but the work itself is lost.

As a side note, it’s worth pointing out the flute thief demon, despite meeting a gruesome end here, enjoyed a literary afterlife of his own. A certain Li Mingfeng (李鳴鳳), the author of a colophon on one of the earliest surviving Zhong Kui paintings, suggests that the (in)famous rebel An Lushan might have been a reincarnation of this specific entity. While I am not aware of any other attempts at providing him with a backstory, in Ming period retellings of the legend, he received a name, Xu Hao (虛耗).

Zhong Kui’s later career

Zhong Kui’s popularity grew after the Tang period, and he arguably eclipsed figures such as the fangxiang (方相) or the baize (白沢) as the demon queller par excellence. Legends about his origin and his first notable act of demon quelling which I summarized above spread far and wide during the reign of the Song dynasty.

After becoming a well defined figure, Zhong Kui came to be most commonly classified as a ghost (鬼; gui). In texts from the Song and Yuan periods he is often labeled more specifically as a “big ghost” (大鬼, dagui) or “ghost hero” (鬼雄, guixiong). However, his popularity effectively made him a god in popular imagination, and as a matter of fact he is referred to as such. His divinity is not exactly conventional, though. This topic is addressed in Fu Lu Shou Xianguan Qinghui 福祿壽仙官慶會 (The Immortal Officials of Happiness, Wealth and Longevity Gather in Celebration) by the Ming playwright Zhu Youdun (朱有燉; 1379-1435). Zhong Kui says himself that unlike his peers, he has no festival to call his own, and receives no regular offerings - and yet, he still vanquishes malicious entities on behalf of humans as long as talismans showing him continue to be distributed.

Interestingly, despite his long career in texts, no images of Zhong Kui older than the thirteenth century are known. This is mostly a matter of selective preservation, though - we know that depictions of him existed as early as in the ninth century, and that they were mass produced, presumably as woodblock prints, in the tenth. However, he didn’t necessarily look similar to his modern depictions. He actually only came to be depicted as a Tang scholar in the Song period. It seems earlier his costume might have varied.

One thing which seemingly remained consistent when it comes to Zhong Kui’s appearance is his facial hair. This feature is even emphasized in many of his epithets, such as “Old Beard” (老髯, Lao Ran), “Bearded Elder” (髯翁, Ran Wong) or “Bearded Lord” (髯君, Ran Jun). It’s possible that this was initially a way to highlight his vitality and his opposition to disease-causing demons.

Tang and Song sources indicate the state of facial hair could be viewed as an indicator of health. There’s even a handful of peculiar anecdotes about certain emperors, like Taizong of Tang or Renzong of Song, believing their facial hair has supernatural healing powers and offering ailing courtiers concoctions in which it was one of the ingredients. There’s no evidence Zhong Kui’s hair was ever believed to serve a similar purpose, though.

Not all of Zhong Kui’s titles revolve around his beard, though. An interesting example is “Nine-Headed Hermit” (九首山人). The intent isn’t to imply he has nine heads, it’s a multilayered pun instead. The character 馗 in Zhong Kui’s name is a combination of 九, “nine”, and 首, “head”. Referring to him as a “hermit”, literally “man of the mountain”, is likely supposed to show that he traverses areas traditionally believed to be inhabited by demons.

The nine-headed snake Xiangliu (wikimedia commons)

Chun-Yi Tsai suggests that this title also highlights Zhong Kui’s physical prowess by implicitly evoking “a nine-headed serpent known for its tremendous strength in Guideways through Mountains and Seas” (presumably Xiangliu).

Zhong Kui’s strength lets him punish his enemies in various unexpectedly creative ways. The earliest sources already mention he could grind vanquished demons in a mill, for instance. References to eating them are particularly common. Depending on the source, Zhong Kui might simply devour them whole, hunt and prepare them like game animals, chop them up to pickle them, mince them to prepare meat snacks, squeeze them to make juice and wine, and so on.

Such comedically gruesome descriptions are generally limited to textual sources, since violence was rarely depicted in other mediums, even in relation to military topics. Wu Daozi’s lost painting was apparently one of the exceptions, as according to a tenth century description it showed Zhong Kui gouging out the eyes of the captured demon.

Zhong Kui’s sister and other assistants

While Zhong Kui is often depicted in the company of nondescript demons, there are relatively few recurring figures associated with him. The main exception is his sister. The Song period painter Gong Kai (龔開) and his contemporary Li Mingfeng (李鳴鳳) simply refer to her as Amei (阿妹), literally “younger sister”, though here it’s apparently a personal name, following Chun-yi Tsai’s interpretation. Her origin is unknown, and she is not present in any of the early variants of the legend.

Zhong Kui Marrying Off His Sister (wikimedia commons)

Today Zhong Kui’s sister is known chiefly from works of art in various mediums which can be broadly subsumed under the label “Zhong Kui marrying off his sister” (鍾馗嫁妹, Zhong Kui jiamei) which proliferated through the Ming and Qing periods. This label is sometimes applied to earlier paintings too, for example Zhong Kui Marrying Off His Sister (鍾馗嫁妹圖, Zhong Kui jiamei tu) is the conventional modern title of a scroll attributed to the poorly known painter Yan Geng (顏庚). A colophon from the Ming period describing this work calls the figure presumed to be Zhong Kui’s sister Ayi (阿姨; an informal way to refer a maternal aunt) as opposed to Amei.

Chun-yi Tsai states it is not impossible that the woman is supposed to be Zhong Kui’s wife, rather than his sister, though. The painting can be dated to the Yuan period, and there is no evidence for the story of Zhong Kui marrying off his sister before the Ming plays - granted, it is not impossible that it was already in circulation earlier. Still, other paintings showing Zhong Kui marrying off his sister only date to the Qing period. Additionally, the procession might be a parody of paintings showing rural marriages or couples moving to a new house.

While as far as I am aware this eventually went out of fashion, in early sources Zhong Kui’s sister could be portrayed as an exorcist herself. An example can be found in one of the sermons of the Chan monk Yuanwu (圓悟; 1063–1135), in which he states that celebrations on the “Double Fifth” (端午節, duanwu jie) - the fifth day of the fifth month - involved a dance of “Zhong Kui and his little sister”. A reference to performers dressed up as the pair (as well as kings of hell, gods of soil and stove, various warrior deities and more) has alsobeen identified in an account of celebrations in Kaifeng from the end of the reign of the Northern Song dynasty.

Similar evidence can be found in art too. For example, Zheng Yuanyou (鄭元祐; 1292-1364) in a poem inspired by a painting titled Zhong Kui’s Sister (馗妹圖; as far as I am aware, this work has not been identified) states that she travels alongside her brother, that she’s armed with a sword, and that demons fear her. A related portrayal of her is known from a critical review of the works of Si Yizhen (姒頤真), a Song dynasty painter. According to Gong Kai, in one of his paintings she is shown in tattered (or unbuttoned - the term used, 披襟, can mean both) clothes, and chases away a boar attacking her brother. He was evidently not fond of this innovation, and criticizes it as “vulgar” and inappropriate.

It needs to be stressed that Gong Kai’s displeasure wasn’t necessarily tied to presenting Zhong Kui’s sister as a demon queller, though. In fact, he is actually the author of the most famous work portraying her in this role.

Gong Kai's take on Zhong Kui's sister and her attendants (wikimedia commons; cropped for the ease of viewing)

Gong Kai depicted Amei in unusual black makeup, which is also worn by female demons accompanying her (note the one carrying a kitty!). This might be a parody of the sanbai (三白; “three whites”) face painting popular in the Song period. She and her attendants wear robes decorated with depictions of the “five poisons” (五毒), a term referring to animals perceived as particularly dangerous and inauspicious. The exact list varies, though centipedes, scorpions and snakes in particular are mainstays. The five poisons are directly associated with Zhong Kui, as he can be invoked to ward them off. Direct evidence first appears in the Qing period in accounts of the well known Dragon Boat Festival, but it’s not impossible this was an earlier development.

It is presumed that Gong Kai’s painting might depict Zhong Kui and Amei looking for a demonic version of Yang Guifei, as indicated by various hints in colophons. Her portrayals in art are quite diverse, but attributing demonic traits to her would be hardly unparalleled - she could even be described as a “palace demon” (宮妖, gong yao). The decline of the Tang dynasty was blamed on her, and metaphorically she might have been invoked to criticize other people believed to improperly use the power granted to them by the imperial court.

Gong Kai’s painting also depicts a less recurring member of Zhong Kui’s entourage. One of the demons carries a fox, specifically a nine-tailed specimen. The association between this animal and Zhong Kui goes all the way back to the early Tang period. In one of the Dunhuang manuscripts, the demon queller’s entourage includes a nine-tailed fox and a baize, who acted as bringers of good luck alongside him. It’s also worth pointing out that in another text from the same site, his mount during the hunt for a wangliang (��魎; I will likely cover this entity a future article, stay tuned) is a “wild fox”.

Chun-Yi Tsai attributes the inclusion of a nine-tailed fox among Zhong Kui’s servants as a “family pet” of sorts to the portrayals of this supernatural creature both as an apotropaic antidote to poison (including the five poisons) and as a demon in its own right. It would be a suitable member of Zhong Kui’s entourage both as a conquered malevolent being and as an amplifier for his exorcistic, protective power.

A further possibility is that the association is the result of wordplay. A new year celebration involving a procession of people dressed up as members of Zhong Kui’s entourage, including his sister and various supernatural attendants, was known as dayehu (打夜胡). The homphony between 胡 and 狐, “fox”, might have resulted in the inclusion of the animal among the helpers.

Post scriptum: Zhong Kui in Japan

Zhong Kui, as depicted in Extermination of Evil (wikimedia commons)

Zhong Kui - or rather Shōki, following the Japanese reading of his name - probably reached Japan in the Insei period. Many other figures originating in China reached a considerable degree of popularity in Japan at roughly the same time - Taishan Fujun, Siming, Wudao Dashen, Pangu, Shennong, the examples keep piling up.

The oldest known Japanese depiction of Zhong Kui, which you can see above, is a painting from the twelfth century set known as Extermination of Evil. It might look a bit outlandish compared to most of the other depictions shown through this article, but I was able to locate a very close Chinese parallel:

A Yuan period depiction of Zhong Kui from the collection of the Beijing Library, via Richard von Glahn’s Sinister Way. Reproduced here for educational purposes only.

This is a Yuan period illustration said to be based on Wu Daozi’s painting. Zhong Kui doesn’t look like a Tang scholar yet, and the jacket and wide-brimmed hat are remarkably similar. It seems safe to assume that the Japanese painter was following a similar model - presumably one of the many now lost early depictions of Zhong Kui.

Slightly antiquated iconography surviving far away from the core area associated with a specific figure would hardly be unparalleled - it has been recently suggested that the baize/hakutaku is a similar case, with Japanese depictions and descriptions matching Tang sources fairly closely, but missing the elements which developed in the Song period or later.

For the most part, Zhong Kui fulfilled a similar role in Japan as in China: he was regarded as a fearsome demon queller, and images representing him were distributed for apotropaic purposes. However, it’s also important to note that there were certain innovations. He arrived in Japan at the brink of the middle ages - theologically speaking an era of unparalleled innovation, during which both native and imported figures were interpreted in unexpected ways, leading to the rise of a new “medieval mythology”. Zhong Kui was hardly an exception from this trend.

A “medieval myth” involving Zhong Kui is known from Hoki Naiden (ほき内伝; “Inner Tradition of the Square and the Round Offering Vessels”), an onmyōdō treatise traditionally attributed to Abe no Seimei, but most likely written by one of his descendants in the fourteenth century. Curiously, Zhong Kui’s name is written in it as 商貴 instead of the expected 鍾馗.

Tenkeisei (wikimedia commons)

In the Hoki Naiden, Zhong Kui is still a queller of malevolent supernatural beings. However, instead of being a scorned scholar, he is a yaksha who became the ruler of Rājagṛha, a city in India. He is said to correspond to both the medieval Japanese deity Gozu Tennō (牛頭天王), and to his celestial “double” Tenkeisei (天刑星; from Chinese Tianxingxing), the “star of heavenly punishment” (I covered him here). They are said to be his manifestations respectively on earth and in heaven.

This equation might seem random at first glance, but both of them actually had a lot in common with Zhong Kui: all three were believed to keep demons, especially those causing diseases, in check. Curiously, the reinterpretation of Zhong Kui as a yaksha turned king can also be found in the Genkō Shakusho (元亨釈書), a Kamakura period Buddhist history book. However, I am not aware of any studies examining it in more detail. I assume identifying him as a yaksha was a result of association with Gozu Tennō (I briefly discussed his yaksha credentials here), rather than the other way around, though.

While Hoki Naiden ultimately pertains more to medieval than modern religion, it’s worth noting that an unconventional take on Zhong Kui is still part of an extant tradition. Through history, Zhong Kui could be identified as a dōsojin (道祖神). This term denotes a class of deities meant to protect roads, crossroads and borders of villages. In parts of the Niigata prefecture this form of him is sometimes referred to as Shōki Daimyōjin (鍾馗大明神) today.

Bibliography

Joshua Capitanio, Epidemics and Plague in Premodern Chinese Buddhism

Bernard Faure, Rage and Ravage (Gods of Medieval Japan vol. 3)

Richard von Glahn, The Sinister Way: The Divine and the Demonic in Chinese Religious Culture

Shih-shan Susan Huang, Picturing the True Form. Daoist Visual Culture in Traditional China

Wilt Idema & Stephen H. West, Zhong Kui at Work: A Complete Translation of The Immortal Officials Of Happiness, Wealth, and Longevity Gather in Celebration , by Zhu Youdun (1379–1439)

Chun-Yi Joyce Tsai, Imagining the Supernatural Grotesque: Paintings of Zhong Kui and Demons in the Late Southern Song (1127-1279) and Yuan (1271-1368) Dynasties

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

For a whole month, a blank space ran where my newspaper column should have been. My phone stayed off, and I refused to see anyone. Let me vanish from the world. Only when it got dark enough for the trees to melt into the gloom would I return home, stumbling alone into the lift. Sometimes there’d be a few letters waiting for me, sometimes nothing at all. I’d sit by the window staring into the empty air all night, slipping into sleep at dawn. I never dreamed.

—Yan Ge, Strange Beasts of China tr. Jeremy Tiang

#she's just like me fr ..#yan ge#strange beasts of china#jeremy tiang#chinese literature#book log#words#mine#solitude

405 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lei Heng, the "Winged Tiger," Kuniyoshi, between 1845 and 1850

#art#art history#Asian art#Japan#Japanese art#East Asia#East Asian art#ukiyo-e#woodblock print#Kuniyoshi#Utagawa Kuniyoshi#Utagawa School#illustration#Chinese literature#Water Margin#Edo period#19th century art

254 notes

·

View notes

Note

From what I understand, your advice is that we shouldn't stick to just one version of a story or consider it the true version. And that a story has several versions. And these versions do not make one less than the other. Like, we can choose one version of the story as long as we understand that there are more versions.

Hello!

Yes this is precisely it. It’s very easy to assume that one way a story is told is the only valid version, but it also neglects how it historically was shared and retold - regardless of if deities are involved. Of course people are allowed to express favoritism, myself having moved from Wuhan, I prefer Wuhanese storytelling.

Did you know there’s roughly 360 different types of regional Chinese Opera that coexist? And with such a large variation in a specific area of performing arts, there’s bound to be more variation in nearly anything else.

Myself and the study of Nezha/Nalakubara has led me down many many different rabbit holes into how he was spread across east and southeast Asia. He appears in India, China, Taiwan, Macau, Hong Kong, Japan, Korea, Malaysia, Singapore, Thailand, Kazakhstan, Tibet, and very likely many other places I have yet to know. It would be very ignorant of me to assume the Chinese Daoist method of worship to be the only acceptable kind - and downright shameful to dismiss how other countries worship him.

It’s a lengthy answer, but I hope I was able to convey my feelings and personal thoughts properly.

#nezha#li nezha#lmk nezha#monkie kid nezha#nezha 2019#the legend of nezha#nezha reborn#nezha lego monkie kid#third lotus prince#chinese religion#chinese mythology#chinese folklore#chinese literature#chinese opera#chinese culture#chinese dance#chinese history

55 notes

·

View notes

Note

Mind if I throw you a curve ball? I’m looking for Chinese writers/poets who were influential on Premodern Japanese literature besides Bai Juyi (aka Bo Juyi, Po Chü-i, Bai Letian, Po Letien, Haku Rakuten, etc.). Tang dynasty poets are pretty awesome but I need to branch out.

Here are a few that we came up with:

Zhuangzi (莊子, Sōshi): Zhuangzi, a Daoist philosopher and writer, influenced Japanese literature through the spread of Daoist and Zen Buddhist thought. His ideas about spontaneity and the unity of all things had an impact on Japanese poets and philosophers.

Tao Yuanming (陶淵明, Tōenmei): Tao Yuanming, a poet of the Eastern Jin Dynasty, was known for his pastoral poetry and themes of rural life. His influence can be seen in Japanese literature, particularly in works that celebrated the beauty of the countryside.

Su Dongpo (蘇東坡, So Tōhaku): Su Dongpo, also known as Su Shi, was a versatile Song Dynasty writer who excelled in poetry, prose, and calligraphy. His philosophical and literary works had an impact on Japanese literature, especially in the fields of poetry and essay writing.

Hopefully this helps!

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

*Originally published in Chinese with the title "Kuángrén Rìjì"; sometimes translated as "A Madman's Diary"

#short stories#short story#diary of a madman#lu xun#chinese language literature#chinese literature#asian literature#19th century literature#book polls#have you read this short fiction?#results

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

a melancholic poem about spring by the Qing Dynasty poet Jiang Chunlin (蒋春霖), translation below by me:

Swallows didn't visit the little courtyard;

there's only a drizzle in the clouded sky.

In a corner by the balustrade, fallen flowers gather in a pile -

This is where the spring returns to die.

Weeping, I bid farewell to the east wind,

and pour a cup of wine to send off the flying catkins.

Even when they turn into drifting duckweeds,

the catkins cannot shed their sorrow -

Fly not to the end of the world!

31 notes

·

View notes

Text

Who says the moon is heartless?

It's followed me a thousand miles.

Po Chü-i, Traveling Moon

#Po Chü-i#Bai Juyi#Traveling Moon#moon#moon quotes#a thousand miles#companionship#full moon#Chinese literature#Chinese poetry#quotes#quotes blog#literary quotes#literature quotes#literature#poetry#poetry quotes#book quotes

343 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is the White Dragon Horse Buddhist?

I was recently contacted by a reader on my main external blog. Part of their question asked:

I heard on the Fifth Monkey [@jttwaudiodrama] production notes for Part 8 that the White Dragon Horse wasn’t really converted to Buddhism and thus never “left his family” and obligations. Would this make him eligible for marriage...?

My answer:

There is some inconsistency in the White Dragon Horse’s story. I can’t recall him officially taking vows during the journey, but the Buddha states in chapter 100 that he had (at some point):

Then he [the Buddha] said to the white horse, “You were originally the prince of Dragon King Guangjin of the Western Ocean. Because you disobeyed your father’s command and committed the crime of unfiliality, you were to be executed. Fortunately you made submission to the Law and accepted our vows ... (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 4, p. 382).

又叫那白馬:「汝本是西洋大海廣晉龍王之子,因汝違逆父命,犯了不孝之罪。幸得皈身皈法,皈我沙門 ...

He is then elevated in rank to become an Aṣṭasenā, a group of eight celestial beings said to be "in attendance when the Buddha speaks the Mahayana sutras" (Buswell & Lopez, 2014, p. 74). The Buddha continues:

... Because you carried the sage monk daily on your back during his journey to the West and because you also took the holy scriptures back to the East, you too have made merit. I hereby grant you promotion and appoint you one of the dragon[ horses] belonging to the Eight Classes of Supernatural Beings (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 4, p. 382).

... 每日家虧你馱負聖僧來西,又虧你馱負聖經去東,亦有功者,加陞汝職正果,為八部天龍馬。」

After transforming back into a dragon, he takes his place atop a Huabiao pillar in paradise:

The elder, his three disciples, and the horse all kowtowed to thank the Buddha, who ordered some of the guardians to take the horse to the Dragon-Transforming Pool at the back of the Spirit Mountain. After being pushed into the pool, the horse stretched himself, and in a little while he shed his coat, horns began to grow on his head, golden scales appeared all over his body, and silver whiskers emerged on his cheeks. His whole body shrouded in auspicious air and his four paws wrapped in hallowed clouds, he soared out of the pool and circled inside the monastery gate, on top of one of the Pillars that Support Heaven (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 4, p. 382).

長老四眾,俱各叩頭謝恩。馬亦謝恩訖。仍命揭諦引了馬,下靈山後崖化龍池邊,將馬推入池中。須臾間,那馬打個展身,即退了毛皮,換了頭角,渾身上長起金鱗,腮頷下生出銀鬚,一身瑞氣,四爪祥雲,飛出化龍池,盤繞在山門裡擎天華表柱上。

A huabiao pillar in Xinghai Square, Dalian City, Liaoning Province, China. Via Wikipedia.

A detail of the huabiao dragon finial. Via Wikipedia.

And lastly, JTTW refers to him as a bodhisattva:

I submit to the Bodhisattva of Vast Strength, the Heavenly Dragon of Eight Divisions of Supernatural Beings (Wu & Yu, 2012, vol. 4, p. 385).

南無八部天龍廣力菩薩。

So given this info, I don’t think he would be involved in a relationship.

Sources:

Buswell, R. E. , & Lopez, D. S. (2014). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press.

Wu, C., & Yu, A. C. (2012). The Journey to the West (Vols. 1-4) (Rev. ed.). Chicago, Illinois: University of Chicago Press.

#White Dragon Horse#bailongma#bailong ma#bai long ma#journey to the west#jttw#xiyouji#lego monkie kid#LMK#Chinese literature#Buddhism

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

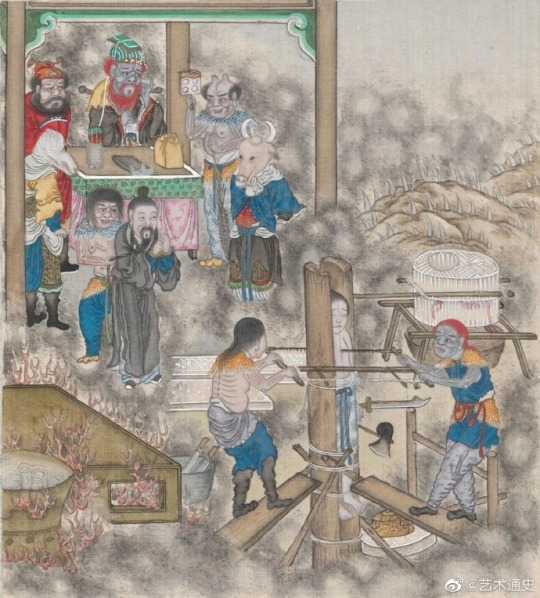

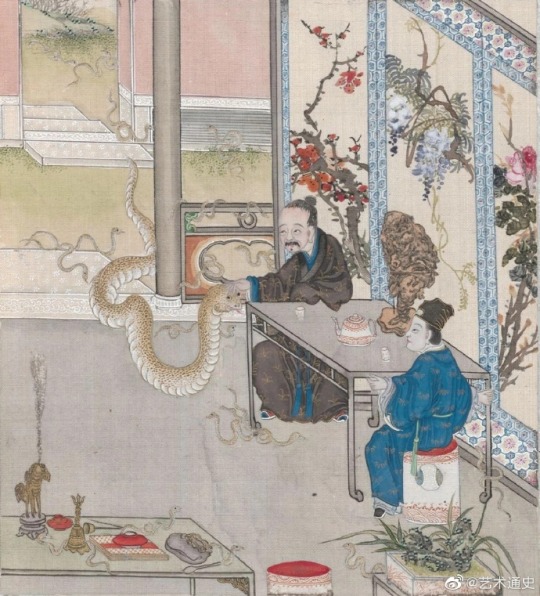

Qing Dynasty Comic Book: Illustration Set for Pu Songling Strange Tales

Qing dynasty comic: a set of illustrations for Strange Tales from the Liaozhai Studio (聊齋志異) by Pu Songling (蒲松龄). It is a collection of short stories about the supernatural, a genre popular in China for several centuries, featuring wizards, foxes and ghosts.

Archived in Austrian National Library.

Photo: ©艺术通史

#ancient china#chinese culture#chinese art#qing dynasty#chinese mythology#chinese painting#chinese calligraphy#ink painting#traditional painting#watercolor#inkart#chinese literature#Chinese fairy tales#fairy tales#supernatural#foxes#fox#ghost#chinese miniatures#miniature#miniature art#miniature painting#weird#weird dreams#weird art

50 notes

·

View notes