#chineseswordsmanship

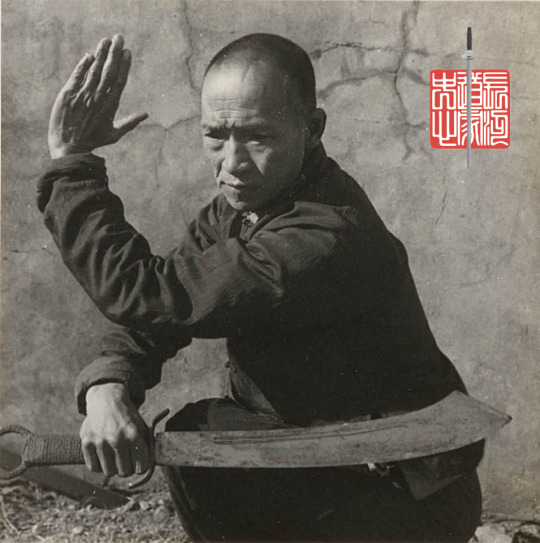

Photo

Swordsman wielding a Dadao

Beijing circa 1930s

Photo by Hedda Morrison

#swordsman#historicalswordsmanship#chineseswordsmanship#swordsmanship#chineseswordfighting#swordfightingskills#swordfightingschool#swordfighting#duanbing#chineseswordplay#swordplay#chineseswordwork#swordwork#chineseswordarts#daoistswordarts#swordarts#chineseswordart#chinesemartialarts#chinesemartialart#刀法#daofa#中國刀法#chineseswords#chinesesword#chineseswordman#kungfuweapons

90 notes

·

View notes

Link

I promised to demystify, but now I’m going to obscure the issue. Mystic is such an elusive substance: always appears where there is no place for it and disappears from where it should be experienced. This is also the case of jian. The practice of the Taoist sword is immersed in childish fantasies, while its true magic is almost lost.

Widely known in China, but overlooked in the West feature of the Taoist sword is that it is used not only for combat, but also in ritual practice. Ritual practice in this context is a broad concept that includes both formal rites and ritual magic. Jian symbolism is related to internal alchemical praxis as well. The guard decorations and the engravings on the blade originally had a ritual and magical significance. However, the true meaning is partially lost, so now it is perceived rather as “traditional patterns”. Jian routines (套路) sometimes contain unobvious ritual elements (steps, fingers’ positions and so on), meaningless for combat, but possessing hidden magical and symbolic connotations. The presence of such inclusions, logically inexplicable both for the practitioner and for the observer, allows imagination to run wild...

#chineseswordsmanship#chinese sword#taoist magic#jian#jianfa#tai chi jian#taoist sword#thunder rites#taoism#taoist practice#internal alchemy#neidan#wudang#kunwu#xuantian shangdi#zhenwu#ritual sword#武当剑#昆吾剑#雷法#內丹#七星剑#玄天上帝

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A High Qing Officer

Armed with a Jian. The vast majority of Manchu Bannermen carried dao, so it is quite unusual to see an official armed in this fashion.We know he is a Bannerman by the green jade thumb around his right thumb.Thumb rings were worn as a symbol of their status as Qiren.

One might think that his man was left handed given that he is wearing his sword on his right hip. But the thumb ring on his right thumb indicated he was indeed right handed. Perhaps there were some social situations where those armed were required to wear their swords on the opposite hip to prevent a quick draw. If this is the case, I am unaware of such a tradition in China. My suggestion is pure speculation. It is also quite possible that the artist simple decided he liked this look better and the swords position on the right hip has nothing to do with how it was actual worn.

19th Century, Chinese School Painting.

#zhongguojianfa#jianfa#chineseswordsmanship#historicalswordsmanship#swordsmanship#chineseswordfighting#swordfighting#duanbing#chineseswordwork#swordwork#swords#chineseswordarts#daoistswordarts#swordarts#swordart#chineseswordart#taijiswordfencing#swordfighter#中國劍法#劍法#劍#kungfuweapons

37 notes

·

View notes

Text

Twilight Jianfa!

After training 3 days at Rodell Laoshi’s St. Paul Seminars, they wanted to test their sword skills. So out they went to the local plaza for some friendly bouting.

Seen on the left is Richard Son Su Meyer, director of Great River Taoist Center Twin Cities. And on the right is Quinatzin De La Torre. Both are long time students of Rodell Laoshi.

Note that both have years of experience in full contact swordplay and are able to control the power of their blows, even at full speed. Less experienced practitioners must don proper swordplay armor, particularly head and eye protection, when bouting.

#jianfa#chineseswordsmanship#jianshu#chineseswordfighting#chineseswordplay#chinesemartialarts#scottmrodell#duanbing#chinesemartialart#swordplay#taijijian#taichisword#yangjiamichuantaijijian#taijiswordfencing#chineseswordfencing#kungfuweapons#swordfightingclasses#swordfightingskills#swordfightingschool#daoistswordarts#daoistswordart#chinesesword#swordarts#swordfight#swordfighter#wudangsword#chineseswordwork#wudangjian#fullcontact#ukchineseswordfighting

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

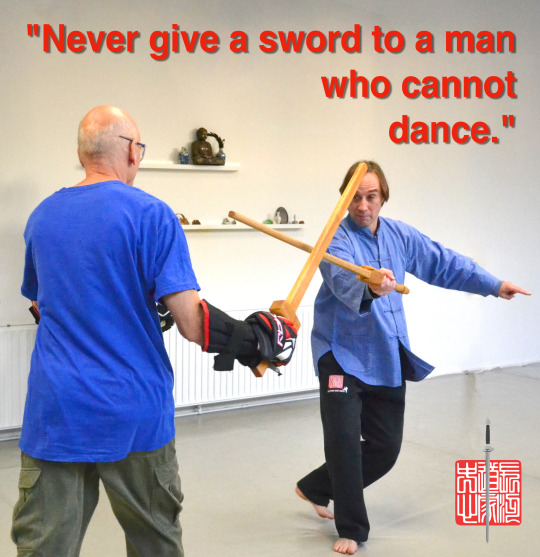

"Never give a sword to a man who cannot dance.” Or at least Confucius is reportedly said so, though this quote is more likely apocryphal than genuine. If he had did indeed written this, Confucius would have no doubt have been using it as a metaphor for not placing someone in a position they are not qualified to fill. If we take this idea literally, then Confucius probably would have actually meant dancing when asked whether or not to trust someone with a Jiàn. Though probably not the sort of dancing you are thinking of. Confucius lived during the later Zhou dynasty (ca. 551–479 BC). During his life, and in many dynasties to come, “Sword Dances” were performed as ritual. The term Jiànwǔ (劍舞, literally, sword dance) was also used to describe the forms used to train soldiers. Minority peoples also practiced war dances to prepare for combat. These ritual court and religious dances required a high degree of precision, flow, and intent. Which is to say nothing of good body mechanics. As do forms practiced by large numbers of men at arms at close quarters when drilling. It then follows that if one is unable to “dance” well with a sword in hand, then it is also unlikely that he’ll flow well in swordplay. Consider if one cannot flow deftly, without hesitation, from one movement to the next in sword forms, or hesitates, rather than moving seamlessly from deflection to cut as one intent, then how can one expect to “dance” smoothly, like a swimming dragon, following and fluidly countering when one’s duifang’s sends blows are raining down?

Lack of preparation in the form of forms (“dances”), training in the Basic Cuts, partner drills, and a methodical progression from fixed step to moving swordplay practice, often results in the sort of slapping together of blades during swordplay derided by past sword teachers. One example from the manual, Zǐwǔ Jiàn by Huáng Hànxūn, advises, “Don’t mutually strike (swords) together at the same time…” And the Yang Family Taijiquan Skill and Essential Points by Huang Yuanxiu records, “The sword is never easy to pass down. Straight forward and back is incomprehensible. If you fake it, cutting like a saber, the old immortal Sanfeng will laugh to death.”

From a modern point of view, if you can’t “dance,” you should at least be cautious about jumping right into swordplay. Dancers move with the rhythm and flow of the music, and with their partners. They intuit the flow and use movements they’ve practiced to follow that pattern. Sounds a good deal like swordplay. If one hasn’t yet learned to “dance” beautifully through the sword form with the same sort of focus and intent of the ancient sword dances, don’t expect to flow with the duifang’s cuts as they rain down, it could be fairly easy to fall into the error

The fix is easy- Practice sword forms as if there’s a duifang there doing his best to cut you. Visual his movements and move with them. Train with a historically accurate sword to avoid misconceptions that arise from light weight, improperly balanced “weapons.” Practice your form mindfully to perfection and you’ll see a difference in your swordplay.

~Scott M. Rodell

#jianfa#chineseswordsmanship#jianshu#chineseswordplay#chineseswordfighting#chinesemartialarts#scottmrodell#duanbing#swordplay#chinesemartialart#scottrodell#yangjiamichuantaijijian#yangstyletaichi#yangstyletaichichuan#taijisword#taichisword#taijijian#zhongguojianfa#ukchineseswordfighting#swordfightingschool#swordfightingskills#swordfightingclasses#swordfighting#chineseswordwork#chineseswordarts#chineseswordart#taijiswordfencing#taijifencing

12 notes

·

View notes

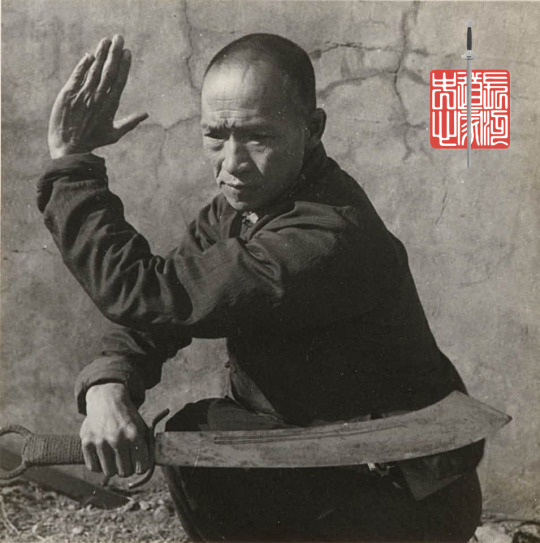

Photo

Swordsman wielding a Dadao

Beijing circa 1930s

Photo by Hedda Morrison

#dadao#dadaodui#chineseswordsmanship#historicalswordsmanship#swordsmanship#chineseswordfighting#swordfightingskills#swordfightingschool#swordfighting#chineseswordplay#swordplay#duanbing#chineseswordwork#swordwork#swords#sword#chineseswordarts#swordarts#swordart#chineseswordart#chinesemartialarts#chinesemartialart#swordfighter#swordtraining#中國刀法#刀法#kungfuweapons

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

#chineseswordplay#chineseswordfighting#daofa#miaodao#qijiguang#dandaofaxuan#dandao#chineseswordarts#chinesemartialarts#duanbing#scottmrodell#swordplay#chinesemartialart#historicalsword#historicalswordsmanship#chineseswordsmanship#ukchineseswordfighting#swordarts#twohandedsword#chineselongsword#Youtube

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Republican Era Chinese Jian with clearly visible differential heat treating of the edge plate that creates a very hard edge. This harden edge makes it excellent for cutting, and it holds its edge quite well. However, the same hardness than makes for superior cutting effectiveness also means that the edge is relatively brittle. For this reason, Chinese Sword Arts standardly deflect with the blade flat rather that parrying with the edge.

Hard blocks with sanmai (three plate) type swords, those of China and Japan, with the edge can lead to a catastrophic failure of the blade.

#jianfa#chineseswordsmanship#jianshu#chineseswordfighting#chineseswordplay#chinesemartialarts#duanbing#chinesemartialart#chineseswordart#chineseswordwork#swordarts#daoistswordarts#zhongguojianfa#中國劍法#劍法#劍#chineseswords#kungfuweapons#historicalswordsmanship#taijijian#taichisword

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Qing Period images of Bannermen drawing their swords are rare, so I was quite please to uncover this portrait of one unsheathing his Jian.

Comparing what we see here with other Qing Period paintings, we should note several consistent details-

When Drawing a Jian, the left hand typically grasps the scabbard near to, or at, the scabbard throat.

The upward draw into a Liao Cut appears to be the favored draw. This upward Liao can be angled to intercept a cut or initiate an advance.

Jian were often slung from a belt by cloth lanyards, however, it appears that in most cases Jianke preferred to carry the sword in the left free from any restraints a lanyard might impose.

While these details of technique and carry are those commonly depicted, we should also keep in mind that these might have also been a matter of artistic convention of the time.

#chinesemartialart#jianfa#chineseswordsmanship#jianshu#chineseswordfighting#scottmrodell#duanbing#chineseswordplay#swordplay#chinesemartialarts#zhongguojianfa#historicalswordsmanship#swordfightingschool#swordfightingskills#swordfightingclasses#swordfighting#chineseswordwork#swordwork#daoistswordarts#daoistsword#taijijian#taijiswordfencing#taijisword#taichisword#劍術#劍法#中國劍法#太極劍#chineseswordarts#chineseswordart

7 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Qing Bannerman

The Dao was standardly slung with the hilt back in this fashion during the Qing period. Judging from this Bannerman's embroidered changpao and leopard skin jacket he is no doubt a high ranking officer.

#manchubannerman#bannerman#qingdynasty#chineseswordsmanship#chineseswordfighting#historicalswordsmanship#chineseswordplay#duanbing#chineseswordwork#chineseswordarts#daoistswordarts#chinesemartialarts#中國刀法#刀法#chineseswords#chineseswordsman#chinesesword

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

The history of the Chinese Fast Sword Draw (出劍法) dates back to the Han dynasty, 2,000 plus years ago. Unfortunately, there are no known manuals for these techniques and historically illustrations are rare. This depiction of a seated swordsman drawing his sword is from a scroll originally painted by Gu Kaizhi ( 顧愷之) in the 4th century. While Gu’s original version of this scroll, The Admonitions of the Instructress to the Court Ladies (女史箴圖) has not survived, later copies of this work have.

The two following later copies of this scroll date to the Tang (dated between the 6th and 8th century AD) and Song dynasties. As such they are likely the oldest known illustrations of a Chinese Swordsman Preforming the Fast Sword Draw (出劍法). They are also the only know depiction of a seated Chinese sword drawn know to date. Given the age of the two paintings, it is difficult to make out the finer details. What we can see is that seated swordsman’s grip is palm out with his fingers wrapping over the grip prepared to draw and strike downward. His rear hand is well back toward the rear of the scabbard, palm down.

A skeptic might understandable suggest that the seated figure is actually wielding a cudgel. Given the lack of visible detail, this would be an understandable suggestion. However, there is no reason for a wooden club to be gripped at the rear end just prior to swinging it. And given that what appears to be bear is just before the seated man, if it were some sort of cudgel and not a sword ready to be drawn, it is more likely he would be gripping it with two hands not holding the the rear end palm down.

Note: the Tang period example of The Admonitions of the Instructress to the Court Ladies is in the collection of the British Museum in London. The Song period (960-1279) example is the property of the Palace Museum in Beijing.

#出劍法#chineseswordsmanship#jianfa#chineseswordfighting#chineseswordplay#scottmrodell#chinesemartialarts#duanbing#chineseswordsman#chineseswordarts#daoistswordarts#swordfighting#chineseswordfencing#taijiswordfencing#swordfightingskills#kungfuweapons#iaido#scottrodell#testcutting#jianshu#chineseswordart#swordarts#swordsmanship#historicalswordsmanship#swordplay#chinesesword#chineseswords#daofa

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Bannerman Drawing his Saber

What is quite interesting about this painting is how the Sword Drawing technique it depicts is consistent with what we have seen before. Note for example, the position of the hand on the scabbard as he draws. It is not at the scabbard throat, but grasped midway along the suspension band. A detail seen in all other illustrations where a Dao (saber) is being draw. Also note that he is drawing with the edge down. Another apparently standard element of the Chinese Quick Sword Draw.

It is also refreshing to see just how Qing swordsmen dressed. Not in the flamboyant colors often worn by martial artists at tournaments today. But in muted grey, functional and not ostentatious.

For more about this painting of BANNERMAN TE'ER DENG CHE, see Bonham’s Auction Website-

https://www.bonhams.com/auction/27991/lot/128/a-rare-and-important-imperial-court-painting-of-the-bannerman-teer-deng-che-qianlong-dated-by-inscription-to-the-wushen-year-corresponding-to-1788-and-of-the-period/

And for a tutorial on Chinese Fast Sword Drawing, see my video on YouTube-

https://youtu.be/6AVk8PQjh2o

#chineseswordsmanship#chineseswordfighting#chineseswordplay#swordplay#chineseswordwork#swordwork#duanbing#swords#sword#daoistswordarts#chineseswordart#swordarts#swordart#taijiswordfencing#chinesemartialarts#chinesemartialart#swordfighter#swordtraining#swordfightingschool#swordfightingskills#中國刀法#刀法#kungfuweapons#出手法

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Merging Jianfa & Daofa in Your Swordplay:

Practitioners of Jianfa looking to explore the depths of Chinese swordsmanship, incorporating Daofa, the art of the saber, can add a more assertive, power orientated flavor to your swordplay.

This journey is not just a weapons switch up; it's about expanding your mindset, augmenting your skill set, while broadening your approach to swordsmanship.

In this guide, we'll navigate through the transition, focusing on practical techniques and insights to enhance your martial arts skills.

The Jian, with its straight, double-edged blade, epitomizes precision, agility, and adaptability, demanding a level of finesse and fine movement.

In contrast, the Dao, featuring heavier cuts, is a single-edged blade, representing power and efficiency in combat.

Uniting Daofa with Jianfa involves more than learning to handle a different sword, it means embracing a different approach in swordplay.

The Dao's point of balance is more forward than the Jian’s. This provides for more powerful cuts and thus a significant shift in technique. Daofa focuses not on the quick, wrist-led maneuvers that are the essence of Jianfa, instead focusing on powerful, elbow-driven techniques.

This style engages larger muscle groups for stronger and more impactful strikes, a key aspect in effectively wielding the Dao.

Starting with Pi Cut from Stirring Deflection

Begin your transformation with a drill common to both Jianfa and Daofa, the Pi cut from a stirring deflection. This provides a familiar base while introducing Dao's unique handling characteristics.

Chan involves a binding or wrapping movement, where the blade circles the body. It's a deflecting technique where the flat of the blade is used to deflect an incoming cut on one side of the body and then continues the motion to circle the blade around the torso, behind the back. This allows for a follow-up cut from the opposite side.

Deflecting with a Chan movement, the empty hand moves inside the blade, close to the chest, and can be employed to momentarily control the opponent’s sword arm as one advances forward. Training this technique introduces practitioners to the closer, more direct combat style found in Daofa. In contrast, Jianfa's prefers maintaining a distance that provides space to maneuver.

After gaining familiarity with the Pi and Hua cuts, it's insightful to progress to the distinctively heavier Kan cut. The Kan is and unique to saber systems, not being present in Jianfa.

Following this, the Duo cut would be the next logical cut to add. While the Duo cut is also present in Jianfa, it’s not made use of as frequently when wielding the straight sword.Training Daofa’s use of the Duo reminds us of why we are evolving our swordplay, merging the mindsets of Jianfa and Daofa, mixing more aggressive and assertive actions into our sword work.

In practice, although the timing of the Duo cut may appear similar to its Jianfa counterpart, it requires a considerably larger window of opportunity, reflecting the bolder and more direct approach of Daofa.

This exploration into the Duo cut provides practitioners with a new perspective on the rhythm shift from the more measured Jianfa to the dynamic and forceful Daofa.

The Pi cut can be likened to the power needed to trim a leaf off a tree, the Kan cut to chopping a thick branch, and the Duo cut to the robust action of felling an entire tree or splitting a log. This progression not only illustrates the escalating power inherent in Daofa techniques but also underscores the distinct tactical mindset required for this style of swordplay.

The Gua cut, though mechanically akin to the Liao cut in Jianfa, takes on a unique role in Daofa. It focuses an aggressive sweeping action to proactively capture the line, reflecting Daofa's assertive and power-oriented nature of Dao swordplay.

Incorporating shield work, especially with durable circular cost effective riot shields, provides insight into how the Dao would have been wielded on the battlefield. This practice not only enhances sword skills but also offers a better understanding of strategic defense and offense in historical combat contexts.

You can use a rattan Tengpai, but these are a lot more costly than a riot shield, which are far cheaper and will hold up to virtually anything you can throw at it during swordplay.

These individual cut drills can be combined into dynamic semi-fixed sparring routines, crucial for experiencing the reactive and adaptive nature of Daofa and preparing for unpredictable combat situations.

Merging Jianfa to Daofa offers an opportunity to evolve your understanding of Chinese swordsmanship, introducing new techniques and strategic thinking. It also adds tactical options to your swordplay, making you less predictable. This journey, embraced with dedication and an open mind, not only enhances your swordplay skills but also enriches your overall approach to swordsmanship. Enjoy the growth and mastery that come with learning the powerful art of the Daofa.

—----

All of the drills and cuts discussed in this guide can be found in the Daofa sections of the Academy of Chinese Swordsmanships Online Archives. Available to all members of the Daofa and Sword Scholars Study paths.

Visit www.chineseswordacademy.com for more details.

#chineseswordsmanship#jianfa#duanbing#chinesemartialarts#chineseswordplay#chineseswordfighting#scottmrodell#jianshu#daofa#scottrodell#daoistswordarts#chineseswordarts#swordfightingclasses#ukchineseswordfighting#taijijian#taijiswordfencing#taijisword#wudangsword#wudangjian#taijidao#taijisaber#swordfightingschool#kungfuweapons#swordfightingskills#chineseswordwork#swordtraining#劍法#刀法#chinesesword#yangjiamichuantaijijian

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Reality Check…

#jianfa#chineseswordsmanship#jianshu#chineseswordfighting#chineseswordplay#scottmrodell#swordplay#duanbing#chinesemartialarts#chinesemartialart#taijisword#wudangsword#wudangjian#daoistswordarts#yangjiamichuantaijijian#taichisword#swordfightingclasses#swordfightingschool#swordclasses#chineseswordwork#chineseswordfencing#taijiswordfencing#fullcontact#swordfighting#swordfigther#swordfights#chineseswordarts#swordarts#historicalswordsmanship#chinesesword

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Full Contact Chinese Swordplay Tournament

Baltimore, 2023

No reason why you can’t close and use your empty hand to control your Duifang’s weapon.

A solid blow to the head or worse counts as a “killing blow” and ends the bout.

#jianfa#chineseswordsmanship#chineseswordfighting#chineseswordplay#duanbing#chinesemartialarts#chinesemartialart#swordplay#zhongguojianfa#ukchineseswordfighting#swordsmanship#historicalswordsmanship#swordfightingschool#swordfightingskills#swordfightingclasses#swordfighting#swordwork#chineseswordwork

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Wang Yen-nien schooling Scott M. Rodell on the finer points of the Yangjia Michuan Taiji Sword Form (楊家秘傳太極劍).

This Sword Form lies at the core of our Sword Work at the Academy of Chinese Swordsmanship.

We also draw upon the Ming period Two-Handed Dandao, the Four Roads Miaodao, the Yang Style Taiji Sword and Saber, and the WW2 Dadao.

#楊家秘傳太極劍#jianfa#chinesemartialarts#duanbing#chineseswordfighting#chineseswordsmanship#jianshu#scottmrodell#chineseswordplay#太極劍#swordclasses#scottrodell#wangyennien#chineseswordarts#chineseswordwork#ukchineseswordfighting#taijiswordfencing#taijisword#swordtraining#劍術#taijijian#chinesesword#chineseswordsman#yangstyletaichi#kungfuweapons#daoistsword#daoistswordsman#swordarts#historicalswordsmanship#swordfightingschool

3 notes

·

View notes