#civil rights activists

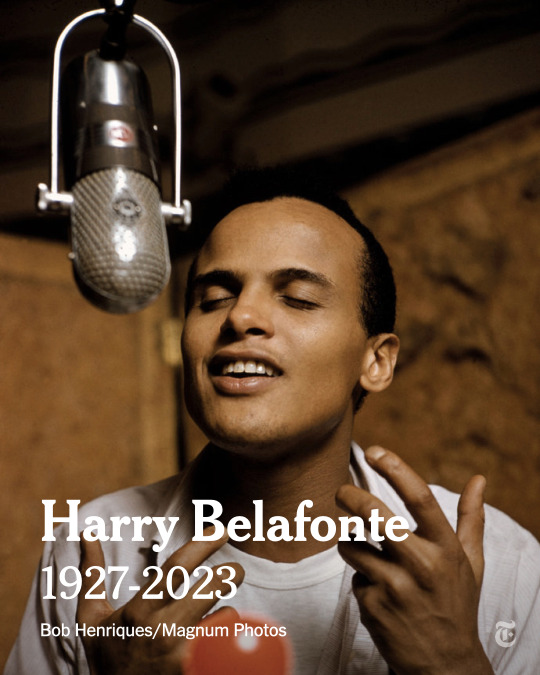

Photo

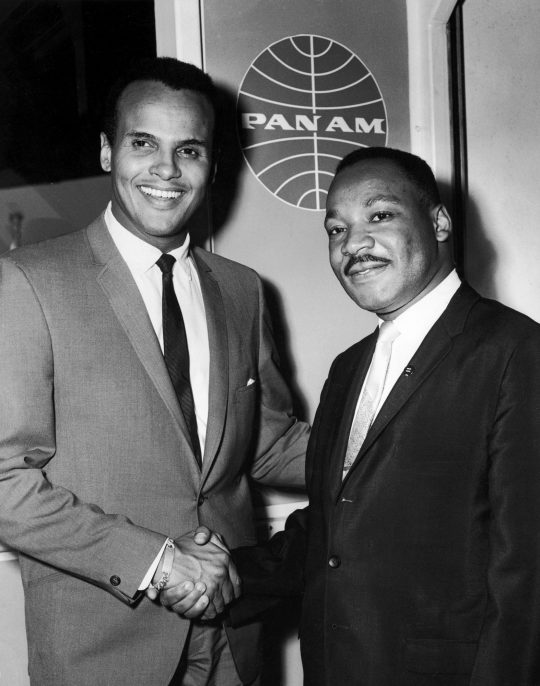

HARRY BELAFONTE (1927- Died April 25th 2023,at 96.Congestive Heart failure). American singer, activist, and actor. As arguably the most successful Caribbean-American pop star, he popularized Jamaican mento folk songs which was marketed as Trinbagonian Calypso musical style with an international audience in the 1950s. His breakthrough album Calypso (1956) was the first million-selling LP by a single artist.Belafonte was best known for his recordings of "The Banana Boat Song", with its signature "Day-O" lyric, "Jump in the Line", and "Jamaica Farewell". He recorded and performed in many genres, including blues, folk, gospel, show tunes, and American standards. He also starred in several films, including Carmen Jones (1954), Island in the Sun (1957), and Odds Against Tomorrow (1959). Belafonte won three Grammy Awards (including a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award), an Emmy Award,and a Tony Award. In 1989, he received the Kennedy Center Honors. He was awarded the National Medal of Arts in 1994. In 2014, he received the Jean Hersholt Humanitarian Award at the Academy's 6th Annual Governors Awards and in 2022 was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in the Early Influence category and was the oldest living person to have received the honour. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harry_Belafonte

#Harry Belafonte#American Singers#American Musicians#American Civil Rights Activists#American Actors#Actors#Civil Rights Activists#Musicians#Calypso music#Notable Deaths in 2023#Notable Deaths in April 2023

396 notes

·

View notes

Text

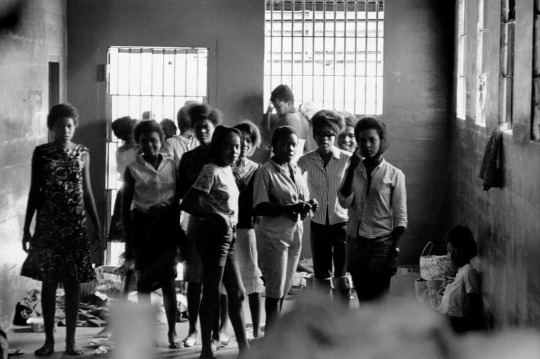

StoryCorps: Leesburg Stockade Girls Recall Time As Civil Rights-Era Prisoners : NPR

Taken in 2016, (left to right) Emmarene Kaigler-Streeter, Carol Barner-Seay, Shirley Green-Reese and Diane Bowens stand outside the stockade building in Leesburg, Ga., where they were jailed in 1963.

The day Martin Luther King Jr. gave his landmark "I Have a Dream" speech in August 1963, a lesser known moment in civil rights history was unfolding in southern Georgia.

More than a dozen African-American girls, ages 12 to 15, were being held in a small, Civil War-era stockade set up by law enforcement in Leesburg, Ga., as a makeshift jail.

Though they were never charged with a crime, the girls had been arrested for challenging segregation in demonstrations in nearby Americus, Ga. For about two months, the girls slept on concrete floors; there was no working toilet or shower. There were minimal food and water deliveries each day.

"The place was worse than filthy," recalled Carol Barner-Seay at StoryCorps in 2016.

Barner-Seay, who's now 68, had been imprisoned there along with Shirley Green-Reese, Diane Bowens and Emmarene Kaigler-Streeter. At StoryCorps, the four women recounted their time together in the stockade.

"Being in a place like that, I didn't feel like we was human," Shirley Green-Reese, now 70, said.

In August 1963, African-American girls were held in a Georgia stockade after being arrested for demonstrating segregation. Left to right: Melinda Jones Williams (13), Laura Ruff Saunders (13), Mattie Crittenden Reese, Pearl Brown, Carol Barner Seay (12), Annie Ragin Laster (14), Willie Smith Davis (15), Shirley Green (14), and Billie Jo Thornton Allen (13). Sitting on the floor: Verna Hollis (15).

Bowens, who's 68, was especially concerned about one of the girls, Verna Hollis. "I was scared Verna was going to die. If she ate, it would just come right back up."

Hollis didn't know that she was pregnant at the time. "We didn't know because we were children," Green-Reese said.

Looking back, Barner-Seay remembered Hollis' strength. "If she complained to anybody, it was under her breath to God, but we never heard it," she said.

Hollis' son, Joseph Jones III, is now 54 years old. A year before Hollis died in 2017, she recorded a StoryCorps interview with him, reflecting on those months she'd been jailed as a teen.

"I was scared and mad that you could treat a human being like they treated us," said Hollis, then 68. "We both could have died in there."

Jones told his mom he, too, was inspired by her strength. "I'm proud of that, and I try to live from that," he said.

'This is us'

The Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee eventually learned where the girls were and sent photographer Danny Lyon to the stockade to photograph them. When Lyon's photographs documenting their squalid living conditions were published, the girls were released.

When Green-Reese went back home, she says she didn't feel welcomed. "When we got out of that stockade, my classmates and my teachers never asked me where I was coming from," she said. "I felt like I didn't fit in, so after high school, I left the area and moved forward."

She took a job with a library in Savannah, Ga. In the archives at work one day, she saw for the first time one of Lyon's photos of the imprisoned girls, including herself, behind bars at the stockade.

"I said, 'This is us.' "

But Green-Reese didn't share the photo with her coworkers. "I didn't want them to know I was in that jail," she said.

It wasn't until 2015 that the women who had been imprisoned in the stockade got together to discuss their time there.

Bowens says she doesn't do well in confined spaces. "Today, when I got in this elevator, I was about to have a heart attack," she said in 2016. "I just don't want to be closed in, and I don't want to be in the dark."

In the StoryCorps podcast, Emmarene Kaigler-Streeter shared what she'd tell the men who locked her up: that she feels sorry for them. "Because they were not looking at us as children," she said. "They were not looking in the hearts. All they were looking at was the fact that we were black."

Green-Reese says the experience is in her "fibers."

"And I still don't like to talk about it," she said, "but this is a part of all of our lives forever."

#They Were Jailed In Squalor For Protesting Segregation#leesburg stockade#civil rights activists#Black Lives Matter#Black History Matters#georgia#americus georgia#systemic racism#falsely detained#adultification

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

A statue of Emmett Till is unveiled in Mississippi : NPR

Emmett Till's statue reflects the afternoon sun, during its unveiling on Friday in Greenwood, Miss.

Rogelio V. Solis/AP

GREENWOOD, Miss. — Hundreds of people applauded — and some wiped away tears — as a Mississippi community unveiled a larger-than-life statue of Emmett Till on Friday, not far from where white men kidnapped and killed the Black teenager over accusations he had flirted with a white woman in a country store.

"Change has come, and it will continue to happen," Madison Harper, a senior at Leflore County High School, told a racially diverse audience at the statue's dedication. "Decades ago, our parents and grandparents could not envision that a moment like today would transpire."

The 1955 lynching became a catalyst for the civil rights movement. Till's mother, Mamie Till-Mobley, insisted on an open-casket funeral in Chicago so the world could see the horrors inflicted on her 14-year-old son. Jet magazine published photos of his mutilated body, which was pulled from the Tallahatchie River in Mississippi.

The 9-foot (2.7-meter) tall bronze statue in Greenwood's Rail Spike Park is a jaunty depiction of the living Till in slacks, dress shirt and tie with one hand on the brim of a hat.

The rhythm and blues song, "Wake Up, Everybody" played as workers pulled a tarp off the figure. Dozens of people surged forward, shooting photos and video on cellphones.

Anna-Maria Webster of Rochester, New York, had tears running down her face.

"It's beautiful to be here," said Webster, attending the ceremony on a sunny afternoon during a visit with Mississippi relatives. Speaking of Till's mother she said: "Just to imagine the torment she went through — all over a lie."

This undated portrait shows Emmett Louis Till, who was kidnapped, tortured and killed in the Mississippi Delta in August 1955 after witnesses said he whistled at a white woman working in a store. AP Photo/AP hide caption

"But you, know, change has a way of becoming slower and slower," said Thompson, the only Black member of Mississippi's current congressional delegation. "What we have to do in dedicating this monument to Emmett Till is recommit ourselves to the spirit of making a difference in our community."

The statue is a short drive from an elaborate Confederate monument outside the Leflore County Courthouse and about 10 miles (16 kilometers) from the crumbling remains of the store, Bryant's Grocery & Meat Market, in Money.

The statue's unveiling coincided with the release this month of "Till," a movie exploring Till-Mobley's private trauma over her son's death and her transformation into a civil rights activist.

The Rev. Wheeler Parker Jr., the last living witness to his cousin's kidnapping, wasn't able to travel from Illinois for Friday's dedication. But he told The Associated Press on Wednesday: "We just thank God someone is keeping his name out there."

He said some wrongly thought Till got what he deserved for breaking the taboo of flirting with a white woman, adding many people didn't want to talk about the case for decades.

"Now there's interest in it, and that's a godsend," Parker said. "You know what his mother said: 'I hope he didn't die in vain.'"

Greenwood and Leflore County are both more than 70% Black and officials have worked for years to bring the Till statue to reality. Democratic state Sen. David Jordan of Greenwood secured $150,000 in state funding and a Utah artist, Matt Glenn, was commissioned to create the statue.

Jordan said he hopes it will draw tourists to learn more about the area's history. "Hopefully, it will bring all of us together," he said.

Till and Parker had traveled from Chicago to spend the summer of 1955 with relatives in the deeply segregated Mississippi Delta. On Aug. 24, the two teens took a short trip with other young people to the store in Money. Parker said he heard Till whistle at shopkeeper Carolyn Bryant.

Four days later, Till was abducted in the middle of the night from his uncle's home. The kidnappers tortured and shot him, weighted his body down with a cotton gin fan and dumped him into the river.

Jordan, who is Black, was a college student in 1955 when he drove to the Tallahatchie County Courthouse in Sumner to watch the murder trial of two white men charged with killing Till — Carolyn's husband Roy Bryant and his half brother, J.W. Milam.

An all-white, all-male jury acquitted the two men, who later confessed to Look magazine that they killed Till.

Nobody has ever been convicted in the lynching. The U.S. Justice Department has opened multiple investigations starting in 2004 after receiving inquiries about whether charges could be brought against anyone still living.

In 2007, a Mississippi prosecutor presented evidence to a grand jury of Black and white Leflore County residents after investigators spent three years re-examining the killing. The grand jury declined to issue indictments.

The Justice Department reopened an investigation in 2018 after a 2017 book quoted Carolyn Bryant — now remarried and named Carolyn Bryant Donham — saying she lied when she claimed Till grabbed her, whistled and made sexual advances. Relatives have publicly denied Donham, who is in her 80s, recanted her allegations. The department closed that investigation in late 2021 without bringing charges.

This year, a group searching the Leflore County Courthouse basement found an unserved 1955 arrest warrant for "Mrs. Roy Bryant." In August, another Mississippi grand jury found insufficient evidence to indict Donham, causing consternation for Till relatives and activists.

Although Mississippi has dozens of Confederate monuments, some have been moved in recent years, including one relocated in 2020 from the University of Mississippi campus to a cemetery where Confederate soldiers are buried.

The state has a few monuments to Black historical figures, including one honoring civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer in Ruleville.

A historical marker outside Bryant's Grocery has been knocked down and vandalized. Another marker near where Till's body was pulled from the Tallahatchie River has been vandalized and shot. The Till statue in Greenwood will be watched by security cameras.

Jordan won applause when he said Friday: "If some idiot tears it down, we're going to put it right back up."

#A statue of Emmett Till is unveiled in Mississippi#emmett till#emmett till statue#mississippi#civil rights activists

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Legends never die REST IN PEACE to 🏀 Bill Russell 👨🏾🦱 and 🎭 Nichelle Nichols👩🏾🦱

#nichelle nichols#bill russell#nba legend#hollywood icons#bostoncelticlegend#boston celtics#star trek#actresses#civil rights activists#rest in paradise#r i p#black king and queen

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

This is so funny, but I don’t hardly agree with Malcolm on anything, but it’s crazy how history repeats itself.

But instead of the conservative party doing the tokenizing liberal party that doing the tokenizing. And they do majority Hollywood.

What happened with the little mermaid how they made Bailey that actress even though Ariel is white people got so excited so happy for that even though it was just to get brownie points from people who want to throw racism in everybody’s face whenever they feel insecure about something.

There’s a bunch of shows, but they do talk about “Black people problems” the funniest part is all equally terrible and it’s not like the shows with the white cast or anything else or any less bad they’re all bad but because they have a black cast or because they’re Black people in it it’s somehow giving Hollywood or any of these institutions even though for decades, they showed you how they do not care for you!

They’re giving Oscars to mediocre to subpar performers or better yet those Hollywood stars on the walk of fame are given to people that don’t even deserve it. They have not even impacted Hollywood in the way that their predecessors have. Majority of those who are sidewalk deserve to be made an impact.

Subscribe to congratulatory ceremonies that they give them themselves created BY themselves, but it’s just ridiculous.

But it just kills me how nobody has enough self-esteem, or self-respect or self-worth to see what they do for what it is and that they’re just barely taking a pseudo version of acceptance.

#Conservative#Liberal#Malcolm X#MLK#civil rights#bob woodson#civil rights activists#black people#white people#tokenism#diversity hire#Hollywood#the Oscar’s#BET awards#Oscars#walk of fame#NAACP#History#history repeating itself#Youtube#black community#Baltimore#economy#us history#the police#cops#Black Americans#Obama#Oprah#low income neighborhoods

0 notes

Text

I’m a firm believer in the passive and small acts of activism.

You’re actively fighting capitalism by resting and taking a break. You’re actively fighting homophobia by wearing a rainbow pin to signify to others your allyship. You’re actively fighting climate change by air drying your hands after washing them. You’re actively fighting childism by letting a minor talk to you about how they’re doing. You’re actively fighting oppressive systems by simply existing.

There have always been others like you, and there always will be others like you. Your existence is rebellion. As long as you’re alive, conservatives and bigots have lost.

You’re a rebel. You’re a warrior. You’re a fighter. And you don’t even know it.

#lgbt#lgbtq#lgbtqia#queer#environmentalism#youth liberation#activism#social activist#climate activists#civil rights activist#human rights activists#political activist#anarchy#anarchist#social justice#human rights#equal rights#civil rights#minorities#minority#oppression#punk

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

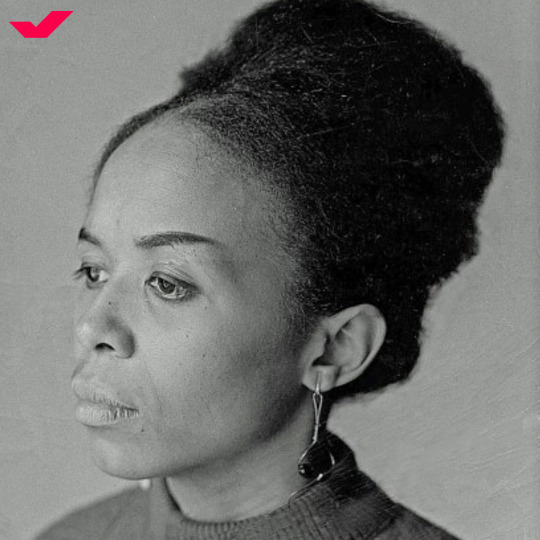

Eunice Kathleen Waymon (February 21, 1933 – April 21, 2003), known professionally as Nina Simone (/ˌniːnə sɪˈmoʊn/), was an American singer, songwriter, pianist, and civil rights activist. Her music spanned styles including classical, folk, gospel, blues, jazz, R&B, and pop.

#nina simone#black tumblr#black history#black literature#black excellence#black community#civil rights#black history is american history#civil rights movement#black girl magic#civil rights activist

1K notes

·

View notes

Photo

We are saddened to hear about the passing of Dorie Ann Ladner, lifelong voting rights activist. 🕊️🗳️

Ms. Ladner participated in every major civil rights protest of the 1960s, including the March on Washington and the march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama. She was a key organizer in her home state of Mississippi, with contributions to the NAACP and Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. In June 1964, she launched a volunteer campaign called “Mississippi Freedom Summer,” with a goal of registering as many Black voters as possible.

We remember and honor Dorie through the words of her sister and fellow activist, Joyce Ladner: as someone who “fought tenaciously for the underdog and the dispossessed,” and “left a profound legacy of service.”

#dorie ladner#dorie ann ladner#voting rights#civil rights#women's history month#mississippi#naacp#sncc#student nonviolent coordinating committee#black voters#black voter#activist#1960s

327 notes

·

View notes

Video

March 1st, 1927 - April 25, 2023

RIP to the great Harry Belafonte.

What a life.

Daylight come and me wan’ go home.

#Harry Belafonte#RIP#Black Culture#Civil Rights#MLK#Jamaican#Heart Failure#Banana Boat#Day-O#Music#Pioneer#Video#Inspiration#Activist

746 notes

·

View notes

Note

OKAY NOW I AM PISSED! now @wakashawty/prncessrindou has deactivated her acc. this is actually heartbreaking to see so many talented black writers leave off of drama and simply just for being black

and if we’re being honest, it’s only going to keep happening. We literally cannot exist in peace in fandom because every time we turn around, someone is being god awful to us and it’s dismissed. To be clear, it’s not ‘drama’, it’s blatant racism and it obviously doesn’t matter as long as it happens to black people bc it’s always seen as some quirky joke. Like damn, maybe we just wanna write and simp too but nobody cares about our feelings. We get sent hate, told to die and that we’re everything but a child of god and we’re expected to just churn out works like it’s business per usual!

#that makes me so sad#but I’m not shocked#ngl I’ve been trying to write#but I feel zero motivation and this is why#like I said they won’t be satisfied until we’re all gone#cherry’s asks 🍒#nonnies 🍒🌹#definitely following her come the 28th#this is bullshit#on the same app I sit and watch my non blk mutuals have the time of their lives#me and other black authors literally gotta play civil rights activists just to be able to write a damn story

66 notes

·

View notes

Photo

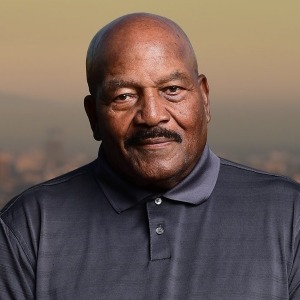

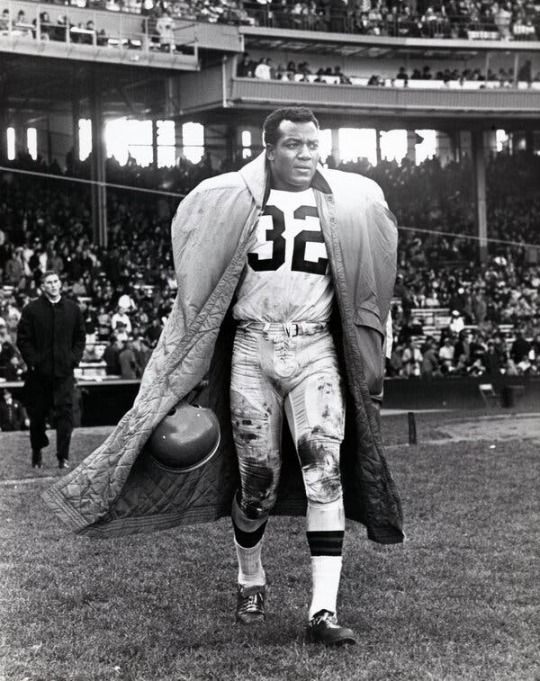

JIM BROWN (1936-Died May 18th 2023,at 87). American football fullback, civil rights activist, and actor. He played for the Cleveland Browns of the National Football League (NFL) from 1957 through 1965. Considered to be one of the greatest running backs of all time, as well as one of the greatest players in NFL history,Brown was a Pro Bowl invitee every season he was in the league, was recognized as the AP NFL Most Valuable Player three times, and won an NFL championship with the Browns in 1964. He led the league in rushing yards in eight out of his nine seasons, and by the time he retired, he held most major rushing records. In 2002, he was named by The Sporting News as the greatest professional football player ever.. Brown was one of the few athletes, and among the most prominent African Americans, to speak out on racial issues as the civil rights movement was growing in the 1950s. He participated in the Cleveland Summit after Muhammad Ali faced imprisonment for refusing to enter the draft for the Vietnam War, and he founded the Black Economic Union to help promote economic opportunities for minority-owned businesses. Brown later launched a foundation focused on diverting at-risk youth from violence through teaching them life skills, through which he facilitated the Watts truce between rival street gangs in Los Angeles.Brown was also an actor,appearing in films such as Ice Station Zebra,Mars Attacks,and leads in films such as 100 Rifles,and The Split. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jim_Brown

#Jim Brown#American Football Players#NFL Football Players#American Sportsmen#American Civil Rights Activists#American Actors#Actors#Civil Rights Activists#Sportsmen#Notable Deaths in 2023#Notable Deaths in May 2023

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

It would be easy to drive right by the Lee County Stockade. The decrepit white concrete building sits in the shadow of a school bus depot and looks like the kind of place that long ago outlived its purpose. On a breezy, overcast day in mid-January, Shirley Green Reese, dressed in a white pantsuit and silver accessories, stood at the stockade door, directing a stream of reporters, filmmakers and locals to step inside.

She began describing the early morning hours of July 1963 when she and a wagonload of at least 14 other girls ranging in age from 12 to 15 were dropped at the jail more than 20 miles from their homes. They had been arrested just a day earlier during a nonviolent civil rights protest at a movie theater in Americus. Holed up in the stockade for weeks, they waited and wondered if their efforts would have an impact.

“I feel very honored that we can share the story and that some people are excited about it and are accepting of it,” Reese said. “Some can’t believe it happened in 1963, and some still have questions about it.”

Known as the Girls of Leesburg Stockade, their story has been shared by news outlets and in books, films and lectures for the past several decades, but to most Americans, including many residents in the southwest Georgia counties where the events took place, the women are largely unknown. They had joined the movement to be seen as Americans with the full force of civil rights, and like many other young protesters of the era, the details of their stories were subsumed by the larger narrative of the civil rights movement.

Caption

Caption

In 2015 Reese and the nine living Leesburg women collectively broke their silence about the time they spent in the Leesburg Stockade.

Now their memories have worn thin. Some of the women recall details that the others do not, and there are disputes about who was actually jailed in the stockade and for how long. But what the girls from Leesburg Stockade now collectively possess that they did not in the past is the desire for their efforts to be seen, heard and understood.

The stockade is now owned by the local school district. There is talk of preserving the building as a historic landmark. Last year, students at the high school worked to have the girls of Leesburg recognized on a historical marker. The marker, in partnership with the Georgia Historical Society, will be dedicated later this year to commemorate the spirit and sacrifice the girls showed during the summer of 1963.

The young seek a role

The road to the Leesburg Stockade began miles away and years before the girls were locked up.

A nascent civil rights effort had been brewing in that pocket of southwest Georgia as the 1950s gave way to the turbulent ’60s. It centered around Albany, and by 1962 had made its way to Americus, 38 miles north.

Children were encouraged to be part of the movement, as they had been in Albany and in Birmingham. It was a controversial tactic, but one that became a signature of the resistance. If a town could lock up its black children to avoid integration, what would it do to their parents?

“Around April of ’63 is when we started asking the SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee) workers, ‘When are we going to go and test these places and restaurants to serve us?’” said Sam Mahone, one of the early leaders of the Americus-Sumter County Movement. “At first, SNCC didn’t think Americus was ready, but the students didn’t want to wait.”

After a series of mass meetings were held at local black churches to energize the crowds, direct action protests began. The first target was the town’s segregated movie theater.

Having slipped away from home on a Saturday afternoon while her parents were downtown, Reese and her best friend Mae Smith-Davis decided to attend the mass meeting at Friendship Baptist Church. When they arrived, the group was already planning to go to Martin Theater.

The pastor and SNCC workers gave them instructions. Don’t talk to anybody. Follow everyone closely. They joined the line and marched toward downtown.

Law enforcement in Americus responded with brute force: water hoses, cattle prods, nightsticks. They arrested protesters by the scores. Some were adults, but the overwhelming number of those taken into custody were teenagers, some as young as 12. When the city jail filled, surrounding counties offered space. Boys and girls were separated, although they were often held in the same building.

‘No swinging doors in Leesburg’

As the protests continued, the stockade in Leesburg filled with girls.

Paddywagons brought them to the stockade, a remote, low-slung structure surrounded by woods and bordered on one side by a lonely stretch of country road.

The building was by then a relic, gloomy and filthy. Bars covered the windows, but much of the glass was broken, giving easy access to bugs. The stockade’s sole toilet would not flush. There was no soap. Water from the shower head trickled in a thin stream. Day in and day out, the girls were fed either scrambled egg sandwiches or four rare hamburgers a day.

Some of the girls were ill and afraid.

Lulu Westbrook Griffin, 69, had joined the group of protesters at the church knowing she would likely end up in jail, but she wasn’t prepared for the trauma she would feel.

“We weren’t used to going off and staying overnight anywhere,” said Griffin, who was 12 at the time. “We went to church, to school. We didn’t even walk out of the house without our parents’ permission.”

Though she was in the company of other girls, Griffin said the experience left her with bouts of crying and nightmares that would persist well into adulthood. She had joined the movement to feel empowered, but her one act of protest left her feeling weak.

Diane Bowens’ activism had been brewing long before she attended the protest at the theater. By then, she was fully invested in the movement. In the stockade, her commitment didn’t waver, said Bowens, then 13. “If you were going to be a part of it, you were going to be a part of it,” she said. “There were no swinging doors in Leesburg.”

Outside world takes notice

As the days turned into weeks, other girls arrived, a signal to the ones already there that the protests continued back in Americus, 27 miles north. But here, the story of the girls of Leesburg Stockade gets muddled. Some reports have said there were more than 30 girls at the stockade arriving and leaving between mid-July and mid-September, but the only visual evidence of girls being held in the stockade, an image shot by a SNCC photographer, pictures 15 girls. Some girls, those from wealthier families in town, have said their parents paid a fee and got them out before the others.

SNCC kept tabs on what counties the children were taken to and where they were being kept, but they didn’t always have names for every child, especially if the child gave a false name. Which is what Carolyn DeLoatch did.

DeLoatch, then 15, had begged her parents to let her get involved in the movement and they’d relented, telling her she could go to mass meetings but to not intentionally get arrested. But there DeLoatch was in August, locked up.

Their days in the stockade were filled with talking, sleeping, praying, singing and wondering when they’d go home, DeLoatch, now 70, said. The monotony was about as intolerable as the food. But by being in Leesburg, she felt she was doing something important.

“It was bearable because it was all of us together,” DeLoatch said. “We were all demonstrating and we wanted people to know that we wanted to be free.”

After several days, her father paid a fine, possibly $45, she said, and she was brought back to Americus. Her father told her he was proud of her, she said, but within three days, her parents shipped her off to a South Carolina boarding school for black girls.

>> RELATED | More historical markers in Georgia, along with more scrutiny

Reese was still in the stockade when Danny Lyon, a young white photographer for SNCC, showed up. Though their parents had come to look in on them and pass fresh clothing and food through the bars, they didn’t have the means or influence to get them out. “Nobody had any rights. Who were they going to go to?” said Reese.

It was mid-to-late August and the girls pressed their faces against the bars staring at Lyon and stretching their arms through the panes framed with broken glass. He lifted his Nikon and started shooting. “I remember touching them through the bars and we said ‘Freedom’ — that was a code word for the civil rights movement,” Lyon said. “The fact that someone from the outside world was there was incredible to them.”

His visit lasted less than 15 minutes, he thinks, but it resulted in the only known images of the girls and the conditions in which they were being held. Not long after the pictures appeared in the black press, the girls were released. It would be the last time for several decades many of them would acknowledge their connection to the Leesburg Stockade.

Readjusting to their lives

On their return to Americus, the girls were dropped right back into their lives.

“I just remember being happy to get out of there,” Bowens said. Though her arrival home was celebrated, Bowens grappled with her feelings. Her mom pressed to know if anyone had sexually assaulted the girls. Her brother threatened to hurt anyone who had, though no one did.

“I just closed off that part of my life,” said Bowens, 69, who would go outside and sit under the house for hours crying. “Just knowing that someone would treat you like that and do that to you. I was feeling sad. I felt like, Is this it? Is this all there is to life?”

As they journeyed from teens to young women, many of the Leesburg girls’ worlds spread beyond the confines of southwest Georgia to New York, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts and beyond. The 15 girls captured in Lyon’s now famous photo would go on to become pastors, civil servants, educators, authors and public speakers.

When Bowens met her husband, she began to feel better. He had been in the movement as well, and they would talk about all the things that happened in Americus. Raising her four children and building a long career as an inspector in the automotive industry changed her outlook, but Bowens still feels sad sometimes. “Things are better now, but basically things are still the same,” she said.

School had been in session for weeks when Reese walked into Sumter High after her release from the stockade. “Not even the teachers asked where I was coming from,” Reese said. “My grades started falling.”

Reese began diving into extracurricular activities — choir, dance, basketball — to keep her mind off those weeks during the summer. “When I first got out, I didn’t feel whole,” she said. She fed off the energy of close friends who were talented, had a positive attitude and were accepting of her.

After high school, her mother sent her to Savannah to live with her aunts. Reese enrolled in Savannah State University and embarked on an educational journey — ultimately earning a doctorate in philosophy from Florida State University — that would bring her some measure of solace and success. She went on to become the first black female athletic director in the state of Georgia.

“I pushed the stockade out of my mind because I had to get an education. That is what my parents had pushed all our lives,” she said.

Though she spent less time in the stockade, DeLoatch was nonetheless marked by the experience. For her, it was an “awakening.” Before Leesburg, she was sheltered by her educator parents, her father a school principal and her mother a librarian in Americus’ segregated school system. They were part of the town’s tiny black middle class.

Leesburg and the Americus movement taught DeLoatch that civil rights would only come with a sustained fight. She went from being voted “most civic minded” at her boarding school to later participating in the Poor People’s Campaign while a college student at Virginia Union in Richmond, she said. Eventually she became a city planner in Chicago and the mother of two. She watched with pride as her son decided to register to vote as soon as he turned 18: no literacy test to pass; no poll tax to pay.

“There was no problem,” DeLoatch said.

Making their voices heard

Leesburg was a moment in DeLoatch’s life but not the only important one.

“I moved on but I used that to help me become the person I am: the kind of person who doesn’t let anybody push them around; the kind of person who is secure in my personhood,” she said.

But the impacts of childhood trauma can linger, said Vincent Willis, assistant professor of interdisciplinary studies at the University of Alabama. Willis is writing the book “Audacious Agitation,” on the experiences of student protesters in southwest Georgia during the civil rights movement. He’s including a chapter on the larger Americus movement and has interviewed some of the women who were jailed in the stockade as girls, he said.

“That 14-year-old girl is still in there somewhere,” Willis said. “The idea that time heals all wounds, I argue against it. They’re told to get over it, that the battle was won, but there are always lingering effects. There’s always psychological damage.”

Griffin was first among the girls of Leesburg Stockade to share her story on a national platform. In 1996, she saw a book, “Memories of the Southern Civil Rights Movement,” with the photographs Lyon had taken at the stockade. “The pictures had no names. I thought, wow, I need to put a name to these faces,” said Griffin, a retired educator.

She would later write a book and hold speaking engagements at schools. When she began planning a documentary, which premiered in Americus in 2003, she contacted some of the other women, she said. Some of them were still reluctant to speak out about the past, fearing repercussion from locals. A few years later, in 2006, a reporter from Essence magazine wrote a story, and some of the women who had previously been reluctant began to speak out.

Reese returned to Americus for good in 2002. She got involved with local civic organizations, including the Boys and Girls Clubs of Americus-Sumter County and the City Council. “I felt I needed to get back in there and help the kids move forward so they would not have to go through what we went through,” Reese said. For years, she had suppressed her feelings about the stockade, but since returning to Americus, she has vowed to keep telling their story.

“We as a people don’t want to address something like this because they feel like things are better now. But we can’t let them forget the past,” Reese said. “Even if they don’t care, I care.”

#Leesburg Stockade Girls#Danny Lyon#americus georgia#civil rights activists#Black Lives Matter#american history#white supremacy#qualified immunity#badges of slavery

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

This brings back some uncomfortable memories. Credit to @neurowild

#neurodiversity#neurodivergent#neurodiverse stuff#neurodivergence#its the neurodivergency#actually neurodiverse#neuro punk#actually autistic#autistic rights activist#autistic rights movement#autistic rights are civil rights#autistic rights are human rights#disability rights activist#disability rights movement#disability rights are human rights#equity

81 notes

·

View notes

Text

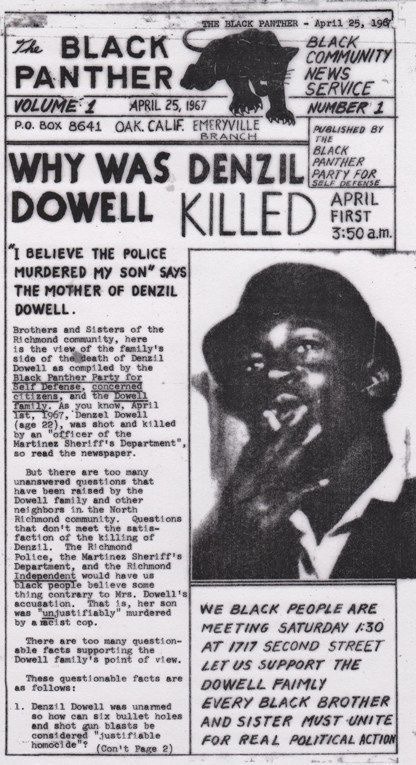

black panther party (bpp) newspaper , April 25, 1967

#black panther party#black panther#bpp#civil rights#civil rights activist#civil rights movement#malcolm x#angela davis#black history is world history#black history is everybody's history#black history#black history matters#civil rights act of 1964

265 notes

·

View notes

Photo

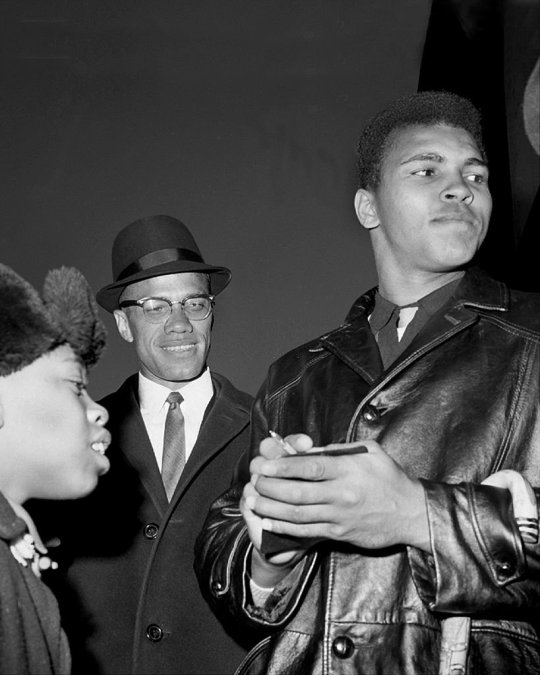

Malcolm X & Muhammad Ali. (1964)

#malcolm x#muhammad ali#black history#black pride#black and white#black unity#boxing#activist#civil rights#black empowerment#vintage#60s#love#photography#photo#portrait#leaders

249 notes

·

View notes

Photo

(via Jim Brown, Football Great and Civil Rights Champion, Dies at 87 - The New York Times)

Jim Brown, the Cleveland Browns fullback who was acclaimed as one of the greatest players in pro football history, and who remained in the public eye as a Hollywood action hero and a civil rights activist, though his name was later tarnished by accusations of violent conduct against women, died on Thursday night at his home in Los Angeles. He was 87.

125 notes

·

View notes