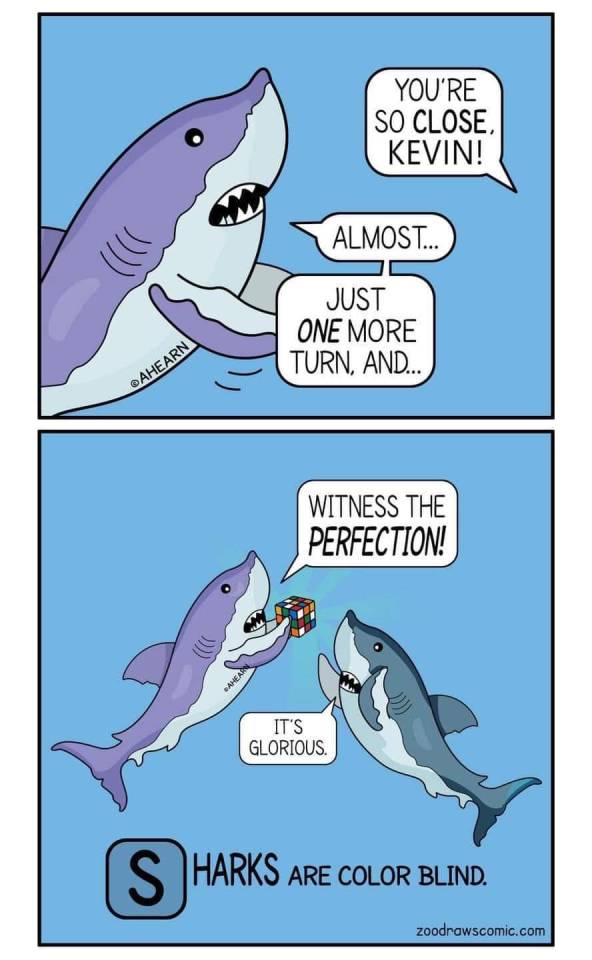

#color blind

Text

#sharks#shark blog#color blind#i didnt know that#respect the locals#shark post#cartilaginous fish#advocacy for sharks#shark awareness#save the sharks#shark facts#meme#funny#shark meme#shark joke#rubriks cube

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

Share please, for increased sample size!!

#color blind#color blindness#vision#color vision#tritanopia#tritanomaly#protanopia#protanomaly#Deuteranopia#Deuteranomaly#colorblind

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Tyler Austin Harper

Published: Aug 14, 2023

The hotel was soulless, like all conference hotels. I had arrived a few hours before check-in, hoping to drop off my bags before I met a friend for lunch. The employees were clearly frazzled, overwhelmed by the sudden influx of several hundred impatient academics. When I asked where I could put my luggage, the guy at the front desk simply pointed to a nearby hallway. “Wait over there with her; he’s coming back.”

Who “he” was remained unclear, but I saw the woman he was referring to. She was white and about my age. She had a conference badge and a large suitcase that she was rolling back and forth in obvious exasperation. “Been waiting long?” I asked, taking up a position on the other side of the narrow hallway. “Very,” she replied. For a while, we stood in silence, minding our phones. Eventually, we began chatting.

The conversation was wide-ranging: the papers we were presenting, the bad A/V at the hotel, our favorite things to do in the city. At some point, we began talking about our jobs. She told me that—like so many academics—she was juggling a temporary teaching gig while also looking for a tenure-track position.

“It’s hard,” she said, “too many classes, too many students, too many papers to grade. No time for your own work. Barely any time to apply to real jobs.”

When I nodded sympathetically, she asked about my job and whether it was tenure-track. I admitted, a little sheepishly, that it was.

“I’d love to teach at a small college like that,” she said. “I feel like none of my students wants to learn. It’s exhausting.”

Then, out of nowhere, she said something that caught me completely off guard: “But I shouldn’t be complaining to you about this. I know how hard BIPOC faculty have it. You’re the last person I should be whining to.”

I was taken aback, but I shouldn’t have been. It was the kind of awkward comment I’ve grown used to over the past few years, as “anti-racism” has become the reigning ideology of progressive political culture. Until recently, calling attention to a stranger’s race in such a way would have been considered a social faux pas. That she made the remark without thinking twice—a remark, it should be noted, that assumes being a Black tenure-track professor is worse than being a marginally employed white one—shows how profoundly interracial social etiquette has changed since 2020’s “summer of racial reckoning.” That’s when anti-racism—focused on combating “color-blindness” in both policy and personal conduct—grabbed ahold of the liberal mainstream.

Though this “reckoning” brought increased public attention to the deep embeddedness of racism in supposedly color-blind American institutions, it also made instant celebrities of a number of race experts and “diversity, equity, and inclusion” (DEI) consultants who believe that being anti-racist means undergoing a “journey” of radical personal transformation. In their righteous crusade against the bad color-blindness of policies such as race-neutral college admissions, these contemporary anti-racists have also jettisoned the kind of good color-blindness that holds that we are more than our race, and that we should conduct our social life according to that idealized principle. Rather than balance a critique of color-blind law and policy with a continuing embrace of interpersonal color-blindness as a social etiquette, contemporary anti-racists throw the baby out with the bathwater. In place of the old color-blind ideal, they have foisted upon well-meaning white liberals a successor social etiquette predicated on the necessity of foregrounding racial difference rather than minimizing it.

As a Black guy who grew up in a politically purple area—where being a good person meant adhering to the kind of civil-rights-era color-blindness that is now passé—I find this emergent anti-racist culture jarring. Many of my liberal friends and acquaintances now seem to believe that being a good person means constantly reminding Black people that you are aware of their Blackness. Difference, no longer to be politely ignored, is insisted upon at all times under the guise of acknowledging “positionality.” Though I am rarely made to feel excessively aware of my race when hanging out with more conservative friends or visiting my hometown, in the more liberal social circles in which I typically travel, my race is constantly invoked—“acknowledged” and “centered”—by well-intentioned anti-racist “allies.”

This “acknowledgement” tends to take one of two forms. The first is the song and dance in which white people not-so-subtly let you know that they know that race and racism exist. This includes finding ways to interject discussion of some (bad) news item about race or racism into casual conversation, apologizing for having problems while white (“You’re the last person I should be whining to”), or inversely, offering “support” by attributing any normal human problem you have to racism.

The second way good white liberals often “center” racial difference in everyday interactions with minorities is by trying, always clumsily, to ensure that their “marginalized” friends and familiars are “culturally” comfortable. My favorite personal experiences of this include an acquaintance who invariably steers dinner or lunch meetups to Black-owned restaurants, and the time that a friend of a friend invited me over to go swimming in their pool before apologizing for assuming that I know how to swim (“I know that’s a culturally specific thing”). It is a peculiar quirk of the 2020s’ racial discourse that this kind of “acknowledgement” and “centering” is viewed as progress.

My point is not that conservatives have better racial politics—they do not—but rather that something about current progressive racial discourse has become warped and distorted. The anti-racist culture that is ascendant seems to me to have little to do with combatting structural racism or cultivating better relationships between white and Black Americans. And its rejection of color-blindness as a social ethos is not a new frontier of radical political action.

No, at the core of today’s anti-racism is little more than a vibe shift—a soft matrix of conciliatory gestures and hip phraseology that give adherents the feeling that there has been a cultural change, when in fact we have merely put carpet over the rotting floorboards. Although this push to center rather than sidestep racial difference in our interpersonal relationships comes from a good place, it tends to rest on a troubling, even racist subtext: that white and Black Americans are so radically different that interracial relationships require careful management, constant eggshell-walking, and even expert guidance from professional anti-racists. Rather than producing racial harmony, this new ethos frequently has the opposite effect, making white-Black interactions stressful, unpleasant, or, perhaps most often, simply weird.

Since the murder of George Floyd in May 2020, progressive anti-racism has centered on two concepts that helped Americans make sense of his senseless death: “structural racism” and “implicit bias.” The first of these is a sociopolitical concept that highlights how certain institutions—maternity wards, police barracks, lending companies, housing authorities, etc.—produce and replicate racial inequalities, such as the disproportionate killing of Black men by the cops. The second is a psychologicalconcept that describes the way that all individuals—from bleeding-heart liberals to murderers such as Derek Chauvin—harbor varying degrees of subconscious racial prejudice.

Though “structural racism” and “implicit bias” target different scales of the social order—institutions on the one hand, individuals on the other—underlying both of these ideas is a critique of so-called color-blind ideology, or what the sociologist Eduardo Bonilla-Silva calls “color-blind racism”: the idea that policies, interactions, and rhetoric can be explicitly race-neutral but implicitly racist. As concepts, both “structural racism” and “implicit bias” rest on the presupposition that racism is an enduring feature of institutional and social life, and that so-called race neutrality is a covertly racist myth that perpetuates inequality. Some anti-racist scholars such as Uma Mazyck Jayakumar and Ibram X. Kendi have put this even more bluntly: “‘Race neutral’ is the new “separate but equal.’” Yet, although anti-racist academics and activists are right to argue that race-neutral policies can’t solve racial inequities—that supposedly color-blind laws and policies are often anything but—over the past few years, this line of criticism has also been bizarrely extended to color-blindness as a personal ethos governing behavior at the individual level.

The most famous proponent of dismantling color-blindness in everyday interactions is Robin DiAngelo, who has made an entire (very condescending) career out of asserting that if white people are not uncomfortable, anti-racism is not happening. “White comfort maintains the racial status quo, so discomfort is necessary and important,” the corporate anti-racist guru advises. Over the past three years, this kind of anti-color-blind, pro-discomfort rhetoric has become the norm in anti-racist discourse. On the final day of the 28-day challenge in Layla Saad’s viral Me and White Supremacy, budding anti-racists are tasked with taking “out-of-your-comfort-zone actions,” such as apologizing to people of color in their life and having “uncomfortable conversations.” Frederick Joseph’s best-selling book The Black Friend takes a similar tack. The problem with color-blindness, Joseph counsels, is it allows “white people to continue to be comfortable.” The NFL analyst Emmanuel Acho wrote an entire book, simply called Uncomfortable Conversations With a Black Man, that admonishes readers to “stop celebrating color-blindness.” And, of course, there are endless how-to guides for having these “uncomfortable conversations” with your Black friends.

Once the dominant progressive ideology, professing “I don’t see color” is now viewed as a kind of dog whistle that papers over implicit bias. Instead, current anti-racist wisdom holds that we must acknowledge racial difference in our interactions with others, rather than assume that race needn’t be at the center of every interracial conversation or encounter. Coming to grips with the transition we have undergone over the past decade—color-blind etiquette’s swing from de rigueur to racist—requires a longer view of an American cultural transition. Civil-rights-era color-blindness was replaced with an individualistic, corporatized anti-racism, one focused on the purification of white psyches through racial discomfort, guilt, and “doing the work” as a road to self-improvement.

Writing in 1959, the social critic Philip Rieff argued that postwar America was transforming from a religious and economic culture—one oriented around common institutions such as the church and the market—to a psychological culture, one oriented around the self and its emotional fulfillment. By the 1960s, Rieff had given this shift a name: “the triumph of the therapeutic,” which he defined as an emergent worldview according to which the “self, improved, is the ultimate concern of modern culture.” Yet, even as he diagnosed our culture with self-obsession, Rieff also noticed something peculiar and even paradoxical. Therapeutic culture demanded that we reflect our self-actualization outward. Sharing our innermost selves with the world—good, bad, and ugly—became a new social mandate under the guise that authenticity and open self-expression are necessary for social cohesion.

Recent anti-racist mantras like “White silence is violence” reflect this same sentiment: exhibitionist displays of “racist” guilt are viewed as a necessary precursor to racial healing and community building. In this way, today’s attacks on interpersonal color-blindness—and progressives’ growing fixation on implicit bias, public confession, and race-conscious social etiquette—are only the most recent manifestations of the cultural shift Rieff described. Indeed, the seeds of the current backlash against color-blindness began decades ago, with the application of a New Age, therapeutic outlook to race relations: so-called racial-sensitivity training, the forefather of today’s equally spurious DEI programming.

In her 2001 book, Race Experts, the historian Elisabeth Lasch-Quinn painstakingly details how racial-sensitivity training emerged from the 1960s’ human-potential movement and its infamous “encounter groups.” As she explains, what began as a more or less countercultural phenomenon was later corporatized in the form of the anemic, pointless workshops controversially lampooned on The Office. Not surprisingly, this shift reflected the ebb and flow of corporate interests: Whereas early workplace training emphasized compliance with the newly minted Civil Rights Act of 1964, later incarnations would focus on improving employee relations and, later still, leveraging diversity to secure better business outcomes.

If there is something distinctive about the anti-color-blind racial etiquette that has emerged since George Floyd’s death, it is that these sites of encounter have shifted from official institutional spaces to more intimate ones where white people and minorities interact as friends, neighbors, colleagues, and acquaintances. Racial-awareness raising is a dynamic no longer quarantined to formalized, compulsory settings like the boardroom or freshman orientation. Instead, every interracial interaction is a potential scene of (one-way) racial edification and supplication, encounters in which good white liberals are expected to be transparent about their “positionality,” confront their “whiteness,” and—if the situation calls for it—confess their “implicit bias.”

In a vacuum, many of the prescriptions advocated by the anti-color-blind crowd are reasonable: We should all think more about our privileges and our place in the world. An uncomfortable conversation or an honest look in the mirror can be precursors to personal growth. We all carry around harmful, implicit biases and we do need to examine the subconscious assumptions and prejudices that underlie the actions we take and the things we say. My objection is not to these ideas themselves, which are sensible enough. No, my objection is that anti-racism offers little more than a Marie Kondo–ism for the white soul, promising to declutter racial baggage and clear a way to white fulfillment without doing anything meaningful to combat structural racism. As Lasch-Quinn correctly foresaw, “Casting interracial problems as issues of etiquette [puts] a premium on superficial symbols of good intentions and good motivations as well as on style and appearance rather than on the substance of change.”

Yet the problem with the therapeutics of contemporary anti-racism is not just that they are politically sterile. When anti-color-blindness and its ideology of insistent “race consciousness” are translated into the sphere of private life—to the domain of friendships, block parties, and backyard barbecues—they assault the very idea of a multiracial society, producing new forms of racism in the process. The fact that our media environment is inundated with an endless stream of books, articles, and social-media tutorials that promise to teach white people how to simply interact with the Black people in their life is not a sign of anti-racist progress, but of profound regression.

The subtext that undergirds this new anti-racist discourse—that Black-white relationships are inherently fraught and must be navigated with the help of professionals and technical experts—testifies to the impoverishment of our interracial imagination, not to its enrichment. More gravely, anti-color-blind etiquette treats Black Americans as exotic others, permanent strangers whose racial difference is so chasmic that it must be continually managed, whose mode of humanness is so foreign that it requires white people to adopt a special set of manners and “race conscious” ritualistic practices to even have a simple conversation.

If we are going to find a way out of the racial discord that has defined American life post-Trump and post-Charlottesville and post-Floyd, we have to begin with a more sophisticated understanding of color-blindness, one that rejects the bad color-blindness on offer from the Republican Party and its partisans, as well as the anti-color-blindness of the anti-racist consultants. Instead, we should embrace the good color-blindness of not too long ago. At the heart of that color-blindness was a radical claim, one imperfectly realized but perfect as an ideal: that despite the weight of a racist past that isn’t even past, we can imagine a world, or at least an interaction between two people, where racial difference doesn’t make a difference.

[ Via: https://archive.today/8zfvc ]

#Tyler Austin Harper#antiracism#antiracism as religion#neoracism#colorblindness#colorblind#color blindness#color blind#religion is a mental illness

7 notes

·

View notes

Note

"What do you mean his scarf is blue? It's not a dark purple?"

"Its- no? It's clearly blue"

"... either way it doesn't suit you"

"HEY-"

-----

"What do you mean pink? I thought it was dirty blond"

"No, it used to be dirty blond, but jow it's pink. You're telling me you didn't notice the change?"

"No????"

-----

Bonus point if reader is colorblind too. With my family (3 colorblinds for 1 normal person) we often argue about colors that all of us see differently, I can totally see that happen with Twi, Leg and Reader, and then the others being like "bro what"

Ok. This made me laugh.

"Either way it doesn't suit you" I nearly choked. 😆

With Reader color blind as well, I can imagine it just as you said.

"It's pink!"

"No, it's orange."

"Obviously, it's white and gold!"

"Tell me you're joking. It's clearly blue and black."

40 notes

·

View notes

Note

Hi, Can you help find a fic? I only remember Peter talking to Tony about his color blind classmate and how the armor was brown to his eyes. So Tony repaints it and the boy sees it on the news....I think some part of it was from the classmate's pov and his name was James maybe?? Algo maybe it was a 5 + 1 Kindle of fic? Maybe??

Thank you to those who contributed to our Follower Outreach Program for helping to locate this story!

5 times Tony Stark ignored Peter Parker (but not for very long) by umbrafix

In which Peter and Tony get to know each other gradually over a series of incidents, communicate far less awkwardly by message than in person, there are pigs, a field trip with spears, Peter lurks, Tony invents, they worry about each other and everything is sweet and nothing hurts.

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

Exposing the Color Blind Glasses Scam

youtube

Wow this is well worth a watch

Just watched and this guy, who is colorblind, does a thorough investigation and interviews with scientists to expose Enchroma and other color blindess glasses scams

2 notes

·

View notes

Video

🙃This is my life

#video#tiktok#tiktoks#funny#lmao#wtf#story time#colorblind#colourblind#color blind#colour blind#bludreamercosplays0

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

On that note....

#blue black dress#white gold dress#blue dress illusion#2015 is BACK#illusion#illusion dress#blue dress white dress#meme#controversy#WHICH COLOR IS IT?#poll#2015 aesthetic#2015 dress#color theory#color blind

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Joke of the day - Color blind

The optometrist said that I’m colorblind. The news came completely out of the pink.

http://www.pinterest.com

View On WordPress

#clean jokes#color blind#cute cat pics#funny jokes#funny one-liners#good jokes#humor#jokes#optometrist#short jokes

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Color Blind

She yearns to live in the forest.

Surrounded by green.

Her hair is dyed a pale red.

Because it reminds her of the trees.

She loves the color of the sky.

And the man’s hat reminds her of such.

The hat is the shade of violets.

When the police ask her to identify the criminal, she says it isn’t him.

The hat is not the right color. She says.

He is free to roam once more.

His flames light up the night sky.

She thinks a storm must be brewing.

His skin, once paler than ivory,

Before the ink seeped in.

Now his arms are covered in blood.

He can still feel the prickling of the needle.

Under the sketches hide the scars,

Beneath the skin.

The pain helps numb the memory.

He is coughing up blood— She thinks it’s vomit.

The water is stained red as it goes down the drain.

It’s the dye from her hair— She’s washing it.

The priest tells her the fires of hell are burning her alive.

She says she feels nothing.

That doesn’t mean the agony is not there.

The sky is blue. She thinks it’s cloudy.

He lights another match. Old habits die hard.

She is surrounded by flames.

The fire transports her to the forest.

She sees the evergreen trees, towering over her.

Are those screams of joy or pain?

The numbness has disappeared.

#poetry#color blind#literature#writing#writers on tumblr#not based on a real story#if you can actual make out what's happening I applaud you#just something I came out with because I was bored#came out bleaker than expected#what makes a poem a poem#oh well pls enjoy#if you are actually colorblind I apologize

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

I truly wonder what Christmas is like for colourblind people

#colorblindness#colourblindness#colour blind#color blind#red-green colorblindness#red-green colourblindness

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

By: Francesca Block

Published: Jan 15, 2024

In the 1960s, when Clarence Jones was writing speeches for Martin Luther King Jr., he used to joke with the civil rights leader: “You don’t deserve me, man.”

“Why?” King would ask.

“I hear your voice in my head. I hear your voice in perfect pitch,” Jones would respond. “So when I write, I can write words that accurately reflect the way you actually speak.”

King would agree. “Man, you are scary. It’s like you’re right in my head.”

And Jones is still, in his mind, having conversations with his friend, who was assassinated at the age of 39 on a Memphis hotel balcony in 1968. Especially now, as America’s racial climate seems to have worsened, despite the fact that King successfully fought to ensure all Americans are given equal protection under the law, regardless of their skin color. A poll from 2021 shows that 57 percent of U.S. adults view the relations between black and white Americans to be “somewhat” or “very” bad—compared to just 35 percent who felt that way a decade ago.

Jones knows exactly what King would have felt about that. He says it out loud, and directs it to his late mentor: “Martin, I’m pissed off at you. I’m angry at you. We should have been more protective of you. We need you. You wouldn’t permit what’s going on if you were here.

“We are trying to save the soul of America.”

[ Jones, behind Martin Luther King Jr. in 1963, wrote: “I saw history unfold in a way no one else could have. Behind the scenes.” ]

I spoke to Jones, 93, two weeks ago as he sat on a beige couch in the humble second-floor apartment in Palo Alto, California, that he shares with his wife. A black-and-white close-up of King sits directly above his head, almost like a north star.

“Regrettably, some very important parts of his message are not being remembered,” Jones said, referring to King’s belief in “radical nonviolence” and his eagerness to build allies across ethnic lines.

“Put in a more negative way,” he added, King’s messages “have been forgotten.”

Jones was a young, up-and-coming entertainment lawyer when he first met King in February 1960. The preacher had turned up on the doorstep of his California home and tried to convince him to move to Alabama to defend him from a tax evasion case. But Jones wasn’t interested.

“Just because some preacher got his hand caught in the cookie jar stealing, that ain’t my problem,” he said in a talk, years later.

But King wasn’t one to give up easily. He invited Jones to attend his sermon at a nearby Baptist church in a well-to-do black neighborhood of Los Angeles. Standing at the pulpit, King spoke to a congregation of over a thousand people, delivering a message that seemed almost tailor-made for Jones.

Jones remembers King talking about how black professionals needed to help their less fortunate “brothers and sisters” in the struggle for equality. He realized, then and there, what an incredible speaker King was, and felt compelled to join his cause.

“Martin Luther King Jr. was the baddest dude I knew in my lifetime,” Jones says.

Jones moved down to Alabama to join King’s legal team. He helped free King of any charges in Alabama, and quickly became one of the leader’s closest confidants, and ultimately, his key speechwriter.

Jones refers to himself and King as “the odd couple,” because, he says, “we were so different.” King was the son of a preacher from a middle-class family in the South. Jones grew up the son of servants, raised by Catholic nuns in foster care in Philadelphia, who he credits with instilling in him “a foundation of self-confidence that was like a piece of steel in my spine.”

He said this confidence propelled him to graduate as the valedictorian from his mixed-race high school just across the border in New Jersey, and then on to Columbia University, where he earned his bachelor’s degree in 1953. After a brief stint in the army, where he was discharged for refusing to sign a pledge stating that he was not a member of the Communist Party, Jones enrolled at the Boston University School of Law, graduating in 1959.

Though Jones was mainly a background figure in the 1960s civil rights movement, it might not have been possible without him. He fundraised for King’s Southern Christian Leadership Conference so successfully that Vanity Fair later called him “the moneyman of the movement.” In 1963, when King was in prison, Jones helped smuggle out his notes, stuffing the words King scrawled on old newspapers and toilet paper into his pants and walking out.

Later, he helped string those notes together into King’s famous address, “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” which argued the case for civil disobedience, and was eventually published in every major newspaper in the country.

Jones then wooed enough deep-pocketed donors, including New York’s then-governor Nelson Rockefeller, to raise the bail needed to release King and many other young protesters from jail.

Jones also helped write many of King’s most iconic speeches—“not because Dr. King wasn’t capable of doing it,” Jones emphasized—“but he didn’t have the time.” Jones crafted the opening lines of King’s “I Have a Dream” speech from his D.C. hotel room on the eve of the 1963 March on Washington. In his book, Behind the Dream, he recounts how he penned their shared vision for a better nation onto sheets of yellow, lined, legal notepaper, many of which ended up crumpled on the floor.

But he didn’t write the most famous words: “I Have a Dream”—that was all King, his book notes. “I would deliver four strong walls and he would use his God-given abilities to furnish the place so it felt like home,” Jones writes about their speech-writing dynamic.

The day after he wrote that speech, Jones stood just fifty feet behind King as he delivered it to the hundreds of thousands gathered on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial. “I saw history unfold in a way no one else could have,” Jones writes. “Behind the scenes.”

The movement King led with Jones by his side helped achieve school integration, the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

So, when asked if America has made any progress on race, Jones is dumbstruck. “Are you kidding?” he said, with shock in his voice. “Any person who says that to the contrary, any black person who alleges themselves to be a scholar, or any white person who says otherwise, they’re just not telling you the truth.

“Bring back some black person who was alive in 1863, and bring them back today,” he adds. “Have them be a witness.”

But after the death of George Floyd in 2020, 44 percent of black Americans polled said “equality for black people in the U.S. is a little or not at all likely.” And “color blindness”—the once aspirational idea of judging people by their character rather than their skin color, which King famously espoused—has fallen out of fashion. The dominant voices of today’s black rights movement argue that people should be treated differently because of their skin color, to make up for the harms of the past. One of America’s most prominent black thinkers, Ibram X. Kendi, argues that past discrimination can only be remedied by present discrimination.

Jones makes it clear he doesn’t want to live in a society that doesn’t see race. “You don’t want to be blind to color. You want to see color. I want to be very aware of color.”

But, he emphasizes: “I just don’t want to attach any conditions to equality to color.”

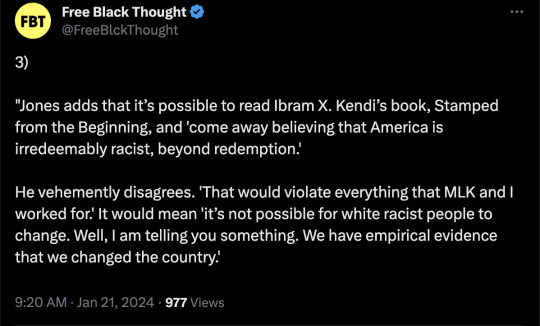

He adds that it’s possible to read Kendi’s prize-winning book, Stamped from the Beginning, and “come away believing that America is irredeemably racist, beyond redemption.”

It’s a theory he vehemently disagrees with. “That would violate everything that Martin King and I worked for,” he said. It would mean “it’s not possible for white racist people to change.”

“Well, I am telling you something,” Jones adds. “We have empirical evidence that we changed the country.”

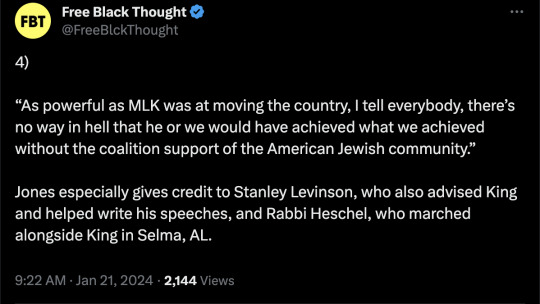

Jones is the first to admit King and his circle didn’t change the country on their own.

“As powerful as he was at moving the country, I tell everybody, there’s no way in hell that he or we would have achieved what we achieved without the coalition support of the American Jewish community.”

Jones especially gives credit to Stanley Levinson, who also advised King and helped write his speeches, and Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel, who marched alongside King in Selma, Alabama. He remembers being on the picket lines and talking to Jewish protesters who told him about their own families’ experiences in the Holocaust.

“There would have been no Civil Rights Act of 1964, no Voting Rights Act of 1965, had it not been for the coalition of blacks and Jews that made it happen,” Jones says.

Now, in the wake of Hamas’s October 7 terrorist attack against Israel, Jones said he fears that relations between the Jewish and the black communities in America are beginning to unravel.

He said he has seen how, days after the attack, college students—many of them black—marched on campus, chanting for the death of Israel.

“It pains me today when I hear so-called radical blacks criticizing Israel for getting rid of Hamas. So I say to them, what do you expect them to do?”

He continues: “A black person being antisemitic is literally shooting themselves in the foot.”

Long before October 7, Jones has proudly shown his allegiance to the Jewish people: a gold mezuzah—the small decorative case, which Jews fix to their door frames to bless their homes—is nailed outside his Palo Alto apartment.

“I’m like an old dog who’s just not amenable to new tricks right now,” Jones says. “I have to go on the tricks that I’ve been taught, that got me where I am at 93 years of age. And those old tricks are: you stay with an alliance with the American Jewish community because it’s that alliance that got us this far.

“I am damn sure, at this time in my life, I’m not going to turn my back. This time is more urgent than ever.”

Meanwhile, Jones worries that some of today’s social justice measures have strayed too far from King’s original message. He points to an ethnic studies curriculum for public schools in California, proposed in 2020, which sought to teach K–12 students about the marginalization of black, Hispanic, Native American, and Asian American peoples.

Jones fiercely opposed the new curriculum recommendations, calling them, in a letter to Governor Gavin Newsom, a “perversion of history” that “will inflict great harm on millions of students in our state.” He wrote that the proposed curriculum excluded “the intellectual and moral basis for radical nonviolence advocated by Dr. King” and his colleagues.

“They were promoting black nationalism,” he told me. “They were promoting blackness over excellence.”

California later passed a watered-down version of the curriculum.

At the same time, Jones feels more conflicted about affirmative action, a policy he believes was grounded in “the most genuine, the most beautiful, the most thoughtful” intentions, and that it helped to “accelerate the timetable. . . to truly give black people equal access.”

Even so, he is pragmatic about the Supreme Court’s decision to strike it down last year. “You had to stop the escalator somewhere.”

[ Jones is still working. He released his autobiography, The Last of the Lions, in August, and is now recording the audiobook. ]

In the immediate years after King’s death in 1968, Jones struggled to find a path forward. He was angry and even considered “taking up arms against the government,” which he blamed for allowing King’s death to happen.

For a while, Jones dabbled in politics—serving as a New York State delegate at the 1968 Democratic Convention—and then in media, purchasing a part of the influential black paper New York Amsterdam News. In 1971, he acted as a negotiator on behalf of some of the inmates behind the Attica prison uprising, unsuccessfully trying to seek a peaceful resolution.

But King’s voice—always in his head—eventually steered him back toward his original purpose.

A father of five, Jones lives with his wife, Lin, just a five-minute walk from the Stanford campus where he maintains an affiliation with the Martin Luther King, Jr. Research and Education Institute. In 2018, Jones co-founded the University of San Francisco’s Institute for Nonviolence and Social Justice to teach the lessons of King and Mahatma Gandhi “in response to the moral emergencies of the twenty-first century.”

He is also the chairman of Spill the Honey, a nonprofit founded in 2012 to honor the legacies of King and Holocaust survivor and Nobel laureate Elie Wiesel. And in August 2023, he released his autobiography, The Last of the Lions, so named because he is possibly the only member of King’s civil rights circle still alive. “There’s an African saying that I often reflect upon when I think about his legacy and my own part in his movement,” Jones writes in his book. “If the surviving lions don’t tell their stories, the hunters will take all the credit.”

Although the eight years he spent with King happened more than half a century ago, Jones told me he now sees his mission as clearly as ever. Asked if he has a message for young black Americans on this Martin Luther King Jr. Day, he doesn’t hesitate.

“Commit yourself irredeemably to the pursuit of personal excellence,” he says emphatically. “Be the very best that you can be. If you do that. . . our color becomes more relevant, because we demonstrate ‘black is beautiful’ not as some slogan, but black is beautiful because of its commitment to personal excellence, which has no color.”

==

What's going on now is what happens when activists and fanatics, such as frauds like Kendi and Nikole Hannah-Jones, construct history curriculum, not actual historians. If they teach the Jewish allyship with the Civil Rights Movements at all, it will be wrapped in conspiracy theory such as "interest convergence."

https://newdiscourses.com/tftw-conspiracy-theory/

This doctrine insists that white people (as the racially privileged group) only take action to expand opportunities for people of color, especially blacks (see also, BIPOC), when it is in their own self-interest to do so, and in which case the result is usually the further entrenchment of racism that is harder to detect and fight. Under interest convergence, every action taken that might ameliorate or lessen racism (see also, antiracism) not only maintains racism, but does so because it was organized in the interests of white people who sought to maintain their power, privilege, and advantage through the intervention.

One of the truly gross and despicable things about frauds like Kendi is that while he pulls every bogus fallacy to assert that nothing has changed - it's a tenet of Critical Race Theory that nothing has changed, racism has only gotten better at hiding itself and becoming more entrenched - his own success blows this conspiracy theory completely out of the water, given how fawning his acolytes are about his wildly overstated wisdom, and the number of white fans he's accumulated who masochistically want to be told how racist they are and how much they hurt black folk every single day.

That's not possible unless racism is both aberrant and socially and culturally unacceptable.

#Clarence B. Jones#Clarence Jones#MLK Day#MLK Jr Day#Martin Luther King Jr#Martin Luther King#Martin Luther King Day#i have a dream#Henry Rogers#Ibram X. Kendi#black nationalism#colorblindness#color blindness#colorblind#color blind#antiracism#antiracism as religion#antisemitism#am yisrael chai#pro palestine#pro hamas#islamic terrorism#israel#palestine#hamas terrorism#hamas war crimes#exterminate hamas#religion is a mental illness

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

So,, I have a pool, right? So my parents like me to check the chemicals pretty often, cuz if you have never had a pool or don't know anyone with one and don't know;

You need to check chlorine, PH, alkalinity etc... But mainly I just check chlorine and ph.

So I check ph by how pink-red the water is in the tube thing.

And chlorine is yellow. The issue? I'm colorblind. Chlorine is always on a scale of water or yellow. Key word, "or".

So I do the test and I walk over to one of my parents and they determine the chlorine level because. It all looks the fuckin same to me lol.

One day, they won't be out there, so I'm gonna have to seek someone out to figure that out. Like a friend or some old dude on the golf course behind my house (I mean behind, like one of the holes is like 5-10 ft from our property line)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

i can very faintly remember what blue and yellow looked like, together they were beautiful despite being polar opposites; even now that i lost the ability to see them, i still love those colours together

#tritanopia#color blindness#colour blindness#color blind#colour blind#colorblindness#colourblindness#colorblind#colourblind#thislilfecker

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

84K notes

·

View notes