#cultural revolution

Text

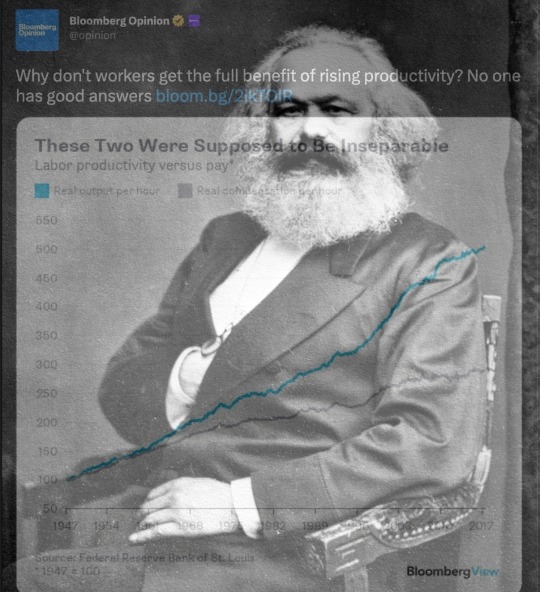

#hail satan#meme#maoism#happy pride 🌈#pride#marxism#socialism#marxism leninism maoism#marxist#capitalist hell#capitalism#communism#leftism#left#support unions#unionstrong#trade unions#cultural revolution#revolución#recession#economy#economics#marxism leninism#mao zedong#karl marx#billionaires#exploiters#transgender#politics#political

535 notes

·

View notes

Text

Small thoughts on the Netflix Three Body Problem adaptation

"We are making it international" they say. They replaced all the international collaboration of world leaders that we see throughout the books with... two British dudes, deciding, alone.

They actually managed to make it less international than the book. They perverted the very themes Liu Cixin brings to his books, about group mentality & collaboration versus the individuals by completely removing all group mentality.

They made Ye Wenjie a unrecognizable shell of herself. Her back is not held up straight. See an old Ye Wenjie cursing, sloushing, moving to England. Is it really Ye Wenjie? It bothers me so much.

They "simplified" the science to a point where nothing is explained, nothing can make it through any kind of analysis of the logic of the things shown & the actions taken.

The futurist headsets we are shown imply that either

1° the Trisolarians are able to send sizable physical objects [which they can't, they can & have sent us two protons].

2° the Trisolarians shared schematics of advanced techs to the ETO for them to develop the headsets, but that's is the one thing they would never do, as their entire plan rely on humans having less advanced tech than they do & not being able to advance it any further.

I thought it was gonna be lesser than the Tencent show. I didn't expect it to be so utterly lacking on all front. "The" boat" scene, the one they spent a 25% of the budget on in the Tencent show, happened in episode 5 & because we know the budget difference between the Netflix show & the Tencent show, we know Netflix didn't use their budget right.

The misguided belief that somehow an American show could show the cultural revolution better to an American audience than a Chinese show can, because of the censorship in China (that though real they clearly do not understand the function & scope of), when they didn't feature a fifth of the storyline the Tencent show did, just in term of the events that took place. What they showed was midly violent & shocking to be sure, but not very accurate to the content of the book. The narration was all wrong. I'll just give small examples:

on the stage when they condemn Ye Wenjie's father (with microphones in front of a huge audience???) they keep saying "lies", which makes no sense, that's not the logic, the charge is propaging western propaganda, upholding Western values, capitalist way of thinking, not lying (I wrote a end of page note to explain that point).

they call Ye Wenjie comrade during her time at the Red Coast (in the book & in the Tencent show her status as a political dissident & therefore NOT a comrade is emphasized).

Ye Wenjie says, "how awesome would it be if China was the first [country to make contact with aliens]" unironically, not in front of the political commissioner asking for something, just enthousiastically. Before she sells out the planets to the Trisolarians.

The inconsistencies are not only baffling deviations from the source materials that display a complete lack of comprehension of Ye Wenjie as a character, as well as an astonishing disregard for the accuracy of the ideology of (Mao-area) communism & the history of Maoist China. They didn't show a lot of content, they could have avoided making such basis mistakes. Given that they kept saying they would not shy away from it, they could have done a better job showing how it was. The Tencent show did a very good job showing how bad it was, in a accurate way. What really pisses me off is that I keep seeing press pieces saying that the Netflix version won't censor "the part of the story taking place during the Cultural Revolution" like the Chinese one like it's such a plus, a reason to watch the American version, by implying to the readers the Tencent version is heavily censored, when in reality the Tencent version spend a lot more than on it than the Netflix one.

Disclaimer, I'm not Chinese, it's not my culture, I don't know the history beyond what a French anarchist who had grounds to dislike French Maoist knows about Maoism, but you don't have to know much to know there is no viewing that time positively, I know how horrrible & damaging the Cultural Revolution was,

And the Tencent show showed that quite well! The political rhetoric fallacies, the bureaucracy, the hypocrisy, how miserable everything is, is shown very well: it's very close to the book.

Censorship does exist & what we know of the shadow-y rules of NRTA is that they wouldn't allow a lot of graphic violence, nudity, sex, ghosts (or BL since 2021...) et caetera, but it's dishonest to pretend that the topic of Cultural Revolution is a taboo that cannot be spoken about, as if the current administration has a positive view on it & would therefore not allow it to be criticized.

The politics of the Cultural Revolution are clearly presented negatively, at length, in the Tencent show, more broadly & accurately than whatever nonsense Netflix did, even if they didn't show one piece of it, a very graphic violent scence which is instead visually & auditorily implied in a short flashback.

NB: "Lies, all lies!". This was so weird to hear for me. Because in French activism we know the ideologies from communism to socialism, going to marxist-leninism & trotskysm to maoism. We still disagree & use the same rhetorics & the same arguments, the culture has changed very little. So my best guess it that "Lying is bad" is a cultural value that the creators cramed it without realizing that it's really not universal, becausee they don't understand communism on any level (they didn't have to make up anything, they just had to keep to the content of the book...)

I don't know if "lying" is a big deal in China, but I know it's not a big deal in my culture & in a Marxist/communist political context, lying is just not "a thing".

They are a lot of charges you can get in a political tribunal (the one I've been party were just verbal affairs). For example, indivualist behavior, liberalism/imperialistic thinking, deceiving the masses with xx propaganda [so they don't revolt when they would if they knew the truth], aspiring to bourgeois comfort [that can mean profiting of other people's labour, not doing enough or not wanting to sacrifice your life for the cause], the worse ones is obviously treason or being counterrevolutionary (working against the revolution). Maoism famously had the three principles one of which being lack of self-criticism (self-reflection so you can do better).

Lying, on this other hand, is not a political charge. It sounds ridiculous.

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

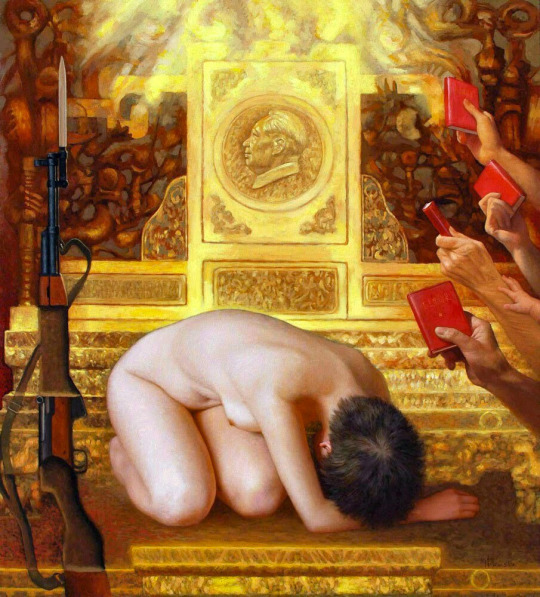

The Little Red Book

546 notes

·

View notes

Text

Writers Yukio Mishima, Kobo Abe, Jun Ishikawa, and Yasunari Kawabata reading the statement "Regarding the Cultural Revolution in China, it is imperative to preserve the self-discipline of learning and art" at a press conference. Photographed at the Hotel Imperial, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo, 28 February 1967.

#yukio mishima#kobo abe#Yasunari Kawabata#Jun Ishikawa#三島由紀夫#安部公房#川端康成#石川淳#cultural revolution#chinese cultural revolution#1967

44 notes

·

View notes

Text

History is repeating itself...

#meme#memes#shitpost#shitposting#humor#funny#lol#satire#funny memes#funny humor#funny meme#dark humor#robert e lee#comedy#china#usa#iraq#cultural revolution#history#history memes#irony#joke#parody

40 notes

·

View notes

Photo

#black power movement#black power#black power button#black america#1960s#60s#cultural revolution#revolution#black people#black culture#retro#vintage#african american#black love#photo#sbrown82

618 notes

·

View notes

Text

I know the Tencent San Ti/ 3 Body show could not include any grand Cultural Revolution scenes because it had to walk a pretty tight line to avoid accusations of engaging in historical nihilism, but to me, episode 11 of the Tencent show is in a way more devastating than the visuals we get in the opening scene of episode 1 of the Netflix show (where we see a full-blown struggle session).

One of the most terrifying abilities that authoritarian states have is to completely isolate a person from all relationships that were ever meaningful to them by forcing people to betray each other. When you've been singled out for criticism and attack, you don't just have to deal with denunciations launched against you by strangers or an anonymous state (which is terrifying enough), you have to listen as your colleagues, your friends, your parents, your children, your spouse, etc. all come forward and denounce you.

What the Tencent show manages to do is quietly build a relationship that provides two characters comfort in an otherwise extremely cold, hostile environment, and then take a hammer and shatter it to pieces. And that is some powerful stuff.

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Dazibaos (big character posters) in the early days of the Cultural Revolution, 1966.

Dazibaos were a means for the masses to bring misdeeds of their bosses or local piliticians to the public attention. Papers would often write pieces based on the dazibaos. This way they could excert pressure on those crititcized, who would then yield and get rid of the problems. In other words, dazibaos were an important means of proletarian democracy.

204 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mao Tsetung says, "Philosophy must liberate itself from the lecture halls. It must enter into each person's life."

Video: Workers of the Shanghai Generator Factory Discuss Marxist Philosophy (1976)

#communism#socialism#maoism#communist#China#maoist#mao tse tung thought#marxism#revolutionary#philosophy#marxism leninism maoism#1970s#70s#life#cultural revolution#GPCR#great proletarian cultural revolution

131 notes

·

View notes

Text

“An eye-opening, heartrending eyewitness account of the atrocities committed against the Mongols by the Communist Party-state. Unforgettable reading and all too pertinent to our times.”

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Almost Nothing Is Worth a War Between the U.S. 🇺🇸 and China 🇨🇳

Americans and Chinese have to rehumanize each other in terms of the way we conceive of our problems and engage.

— By Howard W. French | Foreign Policy | August 21, 2023

A child sitting on a man's shoulder takes a picture as she visits the Bund waterfront area in Shanghai, China, on July 5, 2023. Wang Zhao/AFP Via Getty Images

Midway into my just-completed one-month stay in China, I found myself seated alone in a tasteful restaurant in an upscale shopping mall in Shanghai, where I had gone for dinner.

There, amid dim lighting and soft traditional music, I had a kind of revelation. Bear with me. Against the opposite wall sat a three-generation Chinese family dining together. Two grandparents, slouching a bit, their visages deeply lined, faced in my direction, and seemed to exhibit mild curiosity about what has become a rare sighting recently, even in China’s most cosmopolitan city: a foreigner. They watched closely as I spoke with the waiter in Chinese to complete my order.

Two other people—from all evidence their much taller daughter, who was dressed in the refined way of a well-paid professional, and a small grandchild—sat with their backs to me. I was only able to see their faces when the mother stood up mid-meal to take her girl to the bathroom. In this little glimpse of three generations, an entire world opened up for me, as did a deep sense of alarm over one of the most urgent problems facing all of humanity in these times.

As a former longtime resident of China and someone who has been studying the country since I was a college student many decades ago, I could not prevent myself from trying to imagine the run of experiences the two elders had lived through. I guessed they were roughly my age, meaning in their 60s, but they looked a lot older and more worn than your average well-kept American of similar age.

This meant they would probably have harsh memories of the Cultural Revolution, the decade of political violence and upheaval that began under Mao Zedong in 1966. They or their families may also have suffered even worse tribulations late in the previous decade during the “Great Leap Forward,” when Mao’s crash effort to industrialize resulted in tens of millions of Chinese people starving to death.

Now, the elderly looking man who gazed across the narrow space separating us wore a light blue Gap t-shirt as he picked his way gingerly through a three-course meal, seemingly taking his time to chew. What did he understand of the symbolism of mass consumerism represented in the white logo emblazoned on his shirt? What did he make of the proliferation of this temple of marketing and surplus that is the shopping mall, a cultural phenomenon that contemporary China has made its own? How did he feel about the long curve of his life? Of the grave errors that China had made, but also about where it had ended up, or at least where it stood in this moment? I almost wanted to ask him, but thinking it would have been too much of an intrusion, I restrained myself, with regret.

In those moments, these thoughts impelled me to think about the curve of life in my own country, the United States, too—of how easily one can assume a kind of superior or even triumphalist attitude toward other people in other places. I had just missed being of draft age in the Vietnam War, a senseless tragedy visited upon tens of millions of Southeast Asians, for reasons as specious as many of Mao’s economic and political ideas. I thought of the persistent denial of civil rights for African Americans, which continued in a de jure sense almost into my teenage years. I thought of the devastation to the planet caused by America’s heedless crusade for wealth. Then, based on the evidence, I concluded that bad decisions and human folly are, well, universally human.

The biggest human folly I can presently think of, though, would be something that nowadays seems frighteningly easy to imagine: a war between the United States and China. Until the coronavirus pandemic, I had either lived in or visited China every year since the late 1990s. I plan to write several columns based on my recent return to the country after four years of pandemic-enforced absence. But this is not yet the occasion for a deep exploration for the political, economic, and strategic issues that are pushing to the two countries so far apart and fueling ever greater risk of catastrophe.

I’ll just say here that this is not a situation where, as so many in each country may be inclined to think, if only the other side would stop doing things that threaten or provoke us, the war clouds would dissipate. We have problems together, and if they are to be prevented from causing mass death and destruction, both countries will have to escape the endless loop of reflexively problematizing and sometimes essentializing the other, along with the relentless self-justification.

Many will think me naive, but this has to begin with something all too rare. Americans and Chinese have to rehumanize each other in terms of the way we conceive of our problems and engage. Actually, seeing people in China, like that family across from me at dinner, helped bring this home. But how can this be achieved for the crushing majority of Americans and Chinese who will never visit the other’s country? How can we strip off the layers of surface things that separate us to get in touch with the profound humanity that should unite us? It’s hard work, and the answer is not obvious, but it is urgent.

Since I’m ready to be accused of naivete, I’ll try to start first. There is almost nothing that is worth a war between the United States and China. I’ll come back to the tricky sounding “almost” in a second—it’s actually not as big of an asterisk as some might imagine. Control over Taiwan, which the government of Chinese President Xi Jinping has made into an all-too-public obsession, is not worth the killing that would be unleashed by a Chinese invasion and by any U.S. response in defense of that island. Continued U.S. geopolitical preeminence in the world is also not worth a major armed conflict with China. This is not a call for capitulation, but rather for both countries to find ways to prioritize coexistence and avoid disaster.

As a non-academic historian, I read an inordinate amount about the past, and I have always been struck by the airs of overconfidence and intoxication that have preceded many great past conflicts. On the eve of World War I, for example, elites on both sides—in Germany and Britain—were blithely predicting the troops would be home by Christmas.

Most Americans (and most Chinese) probably spend precious little time thinking about what war would do to their own country. It would be useful to give a wider airing of war game scenarios, such as one carried out recently by the Center for Strategic and International Studies, that make clear just how devastating a conflict could be. In this example, just one of many, Hawaii, Guam, Alaska, and San Diego, California, would all come under withering Chinese attack, up to and potentially including with nuclear weapons. Lest Chinese people think that they would have little to fear by way of direct impact, just for starters, many areas of coastal China, where the country’s population and wealth are heavily concentrated, could face a rain of U.S. missiles.

What are people willing to concede in order to avoid such a fate? In a book I wrote about China’s conception of itself as a great power, I concluded that the United States needed, for starters, to signal a lot more serenity in its competition with China. For at least two decades, my country has behaved as if a bit haunted by the prospect of being overtaken. But for objective reasons—including China’s extraordinarily profound demographic problems, the declining effectiveness of China’s economic policies, and a plethora of domestic challenges in the country—the United States needn’t be. What is more, though, is that the signals of American anxiety, which are rife in the political culture and come through in many U.S. policies, fuel Chinese nervousness, insecurity, and over-assertiveness.

China, for its part, needs to get over its own insecurities. The air of self-confidence it seeks to project is powerfully belied by the constant resort to overt nationalism and to assertions that in its dealings with other countries—or with international bodies like international tribunals governing laws of the sea, for example—only others are capable of incorrect positions. China, by contrast, is not only always right but also righteous.

Beijing is profoundly worried about the staying power of its own political system, but it needn’t obsess, as it claims to, over the supposed efforts of others to undermine it. Whatever threats there are to China’s system of rule come from within China itself. Nobody outside of the country, in other words, is trying to bring down the Communist Party. Only the party itself can achieve this, by failing to reform in step with the desires of the country’s own population.

So how can we restore some confidence on both sides? First the asterisk from above. War should be ruled out except in the case of a direct attack by one side on the other, which means we should rule out attacking each other. China should meanwhile also lower the temperature on Taiwan, in tandem with more reassurances from the United States that Washington does not support the idea of formal independence for the island.

Chinese and American leaders also have to start speaking with each other and meeting much more often face to face. There is really no substitute for this, for as much as what were once called people-to-people exchanges can reinforce a shared sense of humanity, seeing political leaders shake hands and smile and meet across the table to discuss thorny issues separating the two sides can also remind both countries’ public and political classes that there is nothing so hard that it can’t be talked about.

— Howard W. French is a Columnist at Foreign Policy, a Professor at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, and a longtime Foreign Correspondent. His latest book is Born in Blackness: Africa, Africans and the Making of the Modern World, 1471 to the Second World War.

#Foreign Policy#China 🇨🇳 | United States 🇺🇸#Worthless War#Howard W. French#Argument#Cultural Revolution#Vietnam War#Mao’s Economic and Political Ideas#Political | Economic | Strategic Issues#Taiwan 🇹🇼#Hawaii | Guam 🇬🇺 | Alaska | San Diego#Beijing | Washington

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

abolish Israel, free Palestine, Palestinian reunification!

#palestine#death to israel#israel#palestinians#free gaza#gaza strip#gazaunderattack#gaza#revolt#cultural revolution#marxism leninism maoism#mao zedong#maoism#mao#marxist#marxist leninist#marxism#karl marx#marxism leninism#lenin#communist#communism

59 notes

·

View notes

Text

“It is right to rebel”

Mao Zedong

#maoism#communist#communism#marx#lenin#leninism#mao#philosophy#cultural revolution#mao zedong#maoist#leninist#engels#marxism#marxist leninism#marxist leninist

62 notes

·

View notes

Photo

March 19, 1914: Birth of Comrade Jiang Qing, a leader of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution in socialist China.

"When the imperialists and the reactionaries speak of Jiang Qing as the most hated woman in China, they are merely venting their own hatred of a revolutionary. They pour their venom upon her precisely because she was an unflinching and devoted adherent of the cause of revolutionary communism."

- Sam Marcy, "Jiang Qing and the Cultural Revolution"

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Sunday Times Magazine: 'How China Went Red'

26 February 1967

#cultural revolution#chinese cultural revolution#the sunday times magazine#sunday times magazine#chinese communism#china#magazine#Cultural Revolution#文革#中國#文化大革命#1967

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Daily work of the Ministry of Culture

A committee from the Ministry of Culture is currently evaluating all submitted applications. They are looking for a model and actor to correct the film "The Fifth Element". By reshooting some scenes and using AI software, this science fiction classic will be adapted to the androphilic worldview of the Bro Nation. Therefore, the main female character has to be replaced by a very masculine halfman.

6 notes

·

View notes