#cycloneuralia

Photo

Cambrian Explosion #36: Phylum Loricifera

Even more obscure and poorly-understood than the mud dragons, loriciferans weren't even discovered until the 1970s. Over 40 living species of these tiny meiofaunal animals are currently known, but much like the kinorhynchs there are probably many more still to be described.

Less than 1mm long (0.04"), their most distinctive feature is the "lorica", a stiff corset-like casing surrounding their body. They're also the first multicellular organisms discovered able to live completely without oxygen in a deep basin in the Mediterranean Sea.

Traditionally loriciferans have been considered to be part of the scalidophorans, closely related to priapulids and kinorhynchs, but genetic studies have suggested they may actually be much closer related to nematoids and early panarthropods instead.

(The nematoids – nematode worms and horsehair worms – don't have a definite fossil record until the Devonian, and won't be making an appearance in this series. There's one possible larval form from Australia, but with all the disagreements about the mess of early ecdysozoan relationships it's unclear where exactly it actually fits in.)

Loriciferans have a very sparse fossil record – like the kinorhynchs and other meiofauna they're basically "paleontologically invisible" – but there are a few known Cambrian fossils of the group. The minute Eolorica from the late Cambrian of Canada (~497-485 million years ago) is incredibly similar in size and appearance to modern loriciferans, showing that by that time these animals had already taken up the same sort of ecological role as they have today.

But further back in the Cambrian there was something that may actually represent a very early or "stem" loriciferan.

Sirilorica carlsbergi is known from the Sirius Passet fossil deposits in Greenland (~518 million years ago). It was a worm-like animal with a tube of loricate plates around its body and spines around its head, and it was much bigger than modern species, up to about 8cm long (~3").

It suggests that modern-style loriciferans are actually highly miniaturized and neotenous, evolving to retain a tiny larva-like body plan and exploit a fully meiofaunal lifestyle, and lost their original larger worm-like adult forms in the process.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#cambrian explosion#cambrian explosion 2021#rise of the arthropods#sirilorica#loricifera#scalidophora#cycloneuralia#nematoida#ecdysozoa#protostome#bilateria#eumetazoa#animalia#art

187 notes

·

View notes

Audio

[[EDIT] Bioloucos houve um probleminha no nosso áudio e só percebemos agora, acabamos de coloca-lo completo nesse link aqui embaixo. Pedimos desculpas pelo transtorno!!

https://drive.google.com/open?id=1ojXkZdQhzjC3BquGoPtezKbRyRaJR-ja

Olha ai galerinha, o podcast de hoje prontinho pra vocês. Esperamos que gostem!!!!

Aaaah e não esqueçam de acompanhar com as imagens conforme for falado. Ta tudo postado no blog na ordem certinha em que citamos durante o podcast.

Sa, Sté e Tay

0 notes

Photo

Another gastrotrich, this time a macrodasyid, Pseudostomella etrusca. The little tubes along the sides and in the rear secrete an adhesive substance. :3

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cambrian Explosion #34: Phylum Priapulida

Named for their resemblance to human penises, priapulids (or "penis worms") are marine scalidophoran worms that live on or in muddy seafloor sediment, with some species having a surprisingly high tolerance for oxygen-poor environments and toxic levels of hydrogen sulfide. Despite being a rather low-diversity phylum with only around 20 living species, they're widespread and sometimes very numerous, with over 80 adult individuals per square meter (~10ft²) recorded in some locations.

The earliest definite modern-style priapulid in the fossil record comes from the late Carboniferous (~308 million years ago), but their ancestry was probably somewhere in the early Cambrian among the taxonomic mess of palaeoscoloecids and archaeopriapulids.

Xiaoheiqingella peculiaris was a very priapulid-like scalidophoran known from the Chinese Chengjiang fossil deposits (~518 million years ago). Around 1cm long (0.4") it had a ringed spiny body with a swollen proboscis region at the front and a bulbous rear end with a pair of long tail-like appendages.

It's generally considered to be a close relative or early representative of the modern priapulid family Priapulidae, but some analyses have instead suggested it was part of a "stem" priapulid lineage of much earlier forms.

Living alongside it in the Chengijiang region was another potential early priapulid, Paratubiluchus bicaudatus. Also about 1cm long (0.4"), this species was chunkier with a spiny proboscis, a bumpy body lacking rings, and two short rear appendages, and its overall proportions were very similar to the larvae of some modern priapulids.

It may have been closely related to the modern tubiluchid priapulids, but some studies disagree – one analysis even places it as much closer to kinorhynchs and loriciferans than to priapulids!

Both of these species were fairly rare elements of their ecosystem, and seem to have had very similar ecologies to each other. They would have been burrowing carnivores using their retractable proboscises to grab small invertebrate prey, sometimes also feeding detritivorously on decaying organic matter in the mud around them.

Their anatomical and ecological similarities to modern priapulids suggest that the group as a whole rapidly developed in the early Cambrian and then just… didn't ever really need to change their body plan or lifestyle much for the next half a billion years.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#cambrian explosion#cambrian explosion 2021#rise of the arthropods#priapulid#penis worm#xiaoheiqingella#paratubiluchus#scalidophora#cycloneuralia#ecdysozoa#protostome#bilateria#eumetazoa#animalia#art#penis mention#tumblr is going to flag this post so fast

104 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cambrian Explosion #35: Phylum Kinorhyncha

After the slightly unfortunately-shaped priapulids, let's move on to something much safer-for-work: dragons!

More accurately, kinorhynchs, tiny spiky scalidophoran worms with the delightful common name of "mud dragons". These animals weren't even discovered until the mid-1800s and are so small – less than 1mm (0.04") in size – that they're considered to be "meiofauna", wriggling around between grains of sediment using the spines on their heads to pull themselves along.

They're a widespread and abundant phylum with around 300 known living species, but they're also a very understudied group. Only a handful of scientists specialize in them worldwide and most research on them has been done in just the last 60 years, and so there are thought to be many many more species still out there to be discovered.

While these little dragons must have diverged from other scalidophorans at least as far back as the early Cambrian, they have basically no fossil record at all. A ghost lineage of over half a billion years.

Currently the only known exceptions to this are a few incredibly rare fossils from the early Cambrian of China. The recently-discovered Qingjiang fossil deposits (~518 million years ago) include some currently-undescribed specimens up to 4cm long (~1.5"), and if these do turn out to be kinorhynchs they indicate that modern forms may be highly miniaturized versions of much larger ancestors.

And some slightly older fossils from Sichuan, dating to about 535 million years ago, give us another possible ancient mud dragon: Eokinorhynchus rarus.

This species was much smaller than the Qingjiang forms but still twice as big as modern kinorhynchs at around 2mm long (0.8"). It had more body segments than living mud dragons, and a different pattern of spiny armor, suggesting it was probably part of an early stem-kinorhynch lineage rather than a true member of the group.

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#cambrian explosion#cambrian explosion 2021#rise of the arthropods#eokinorhynchus#kinorhyncha#mud dragons#scalidophora#cycloneuralia#ecdysozoa#protostome#bilateria#eumetazoa#animalia#art#cambrian dragons

92 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Cambrian Explosion #33: Early Scalidophora

The earliest branches of the ecdysozoan evolutionary tree are made up of the scalidophorans – animals with spiny retractable proboscises, represented today by the worm-like priapulids and kinorhynchs, and (sometimes*) the weird little loriciferans.

The first definite scalidophoran fossil is the tiny priapulid-like Eopriapulites from the early Cambrian about 535 million years ago, suggesting that the group probably originated from Acosmia-like ancestors not long before that point.

By the mid-Cambrian the most abundant early scalidophorans were the worm-like palaeoscolecids, and archaeopriapulids, with some species known from hundreds or even thousands of specimens. These groups don't seem to have really been distinct lineages but were instead probably more like paraphyletic or "wastebasket" collections of similar-looking early wormy forms, with varying evolutionary relationships to each other and to other scalidophorans and cycloneuralians.

But whatever they were, some of these worms were also fairly successful during their time, with palaeoscolecids lasting for around 100 million years well past the Cambrian and up until the end of the Silurian.

Found in the Chinese Chengjiang fossil deposits (~518 million years ago), Cricocosmia jinningensis was a common palaeoscolecid which grew up to about 7cm long (2.75"). Like other palaeoscolecids it had a long ringed body covered in armor plates, a retractable spiny proboscis, and hooks on its rear end, and it generally lived in burrows in the seafloor.

A row of large spines running along each side of its body may have been used for traction, helping it crawl along the surface of the sediment when out hunting or disturbed from its burrow, and it was occasionally a host for the weird little bowling-pin shaped gnathiferan Inquicus.

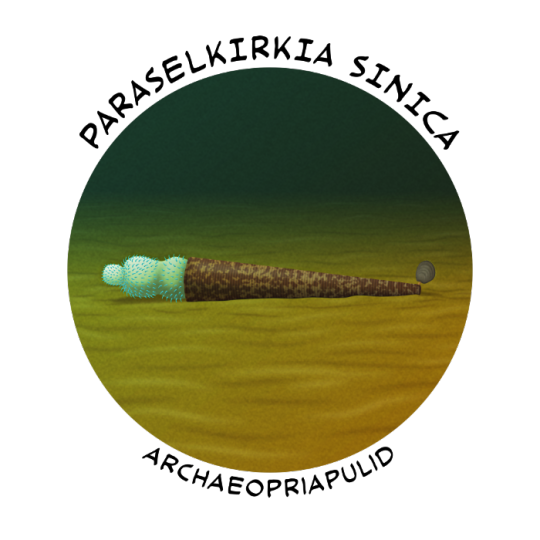

Paraselkirkia sinica was an archaeopriapulid, known from both Chengjiang (~518 million years ago) and the Xiaoshiba Lagerstätte (~514 million years ago). About 2cm long (~0.75"), it was another common element of the Chinese Cambrian ecosystem, often found in dense clusters of individuals.

While most of its anatomy was very similar to modern priapulids, with a retractable spiny proboscis, it's distinctive for having its body enclosed inside a conical organic-walled tube, similar to its close relative Selkirkia from the younger Canadian Burgess Shale.

Traditionally it's been interpreted as living vertically embedded in the seafloor, but the presence of juvenile brachiopods attached to the rear end of some tubes suggests that it actually spent most of its time laying on the sediment surface, probably able to move itself around to some degree and only shallowly burrow.

Some specimens of Paraselkirkia have also been found with clusters of eggs preserved inside their bodies, with a reproductive system that looks almost identical to that of modern priapulids.

( * Morphological and molecular studies still don't agree if loriciferans are closer related to scalidophorans, nematoids, or panarthropods. It's also not entirely clear whether scalidophorans themselves are even a distinct lineage or are more of an "evolutionary grade" of early ecdysozoans. Sometimes scalidophorans and nematoids are also considered to be part of a larger grouping called cycloneuralians, but this might also be more of a "grade" than a distinct lineage.

Basically there's a lot of disagreement in early ecdysozoan relationships and it's only going to get worse once we get to the actual arthropods.)

———

Nix Illustration | Tumblr | Twitter | Patreon

#science illustration#paleontology#paleoart#palaeoblr#cambrian explosion#cambrian explosion 2021#rise of the arthropods#cricocosmia#palaeoscolecida#paraselkirkia#archaeopriapulida#scalidophora#cycloneuralia#ecdysozoa#protostome#bilateria#eumetazoa#animalia#art

109 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Hey galera, tudo bem com vocês?

No podcast de hoje falamos sobre o grupo Cycloneuralia, que é muito interessante! Temos representantes que são velhos conhecidos nossos, como as Lombrigas que fazem parte do Filo Nematoda, como os que a gente quase não ouve falar (cof cof Loricifera). Vimos que eles são muito importantes e que a extinção levaria a um grave desequilíbrio ecológico.

Nessa imagem, podemos observar um cladograma que são classificados esses filos, de acordo com as sinapomorfias (características que são próprias de um filo/classe/ordem/etc e são utilizadas para diferenciar das demais ordens/classes/filos/etc) que os unem, espero que tenha ajudado a visualizar melhor.

Bom, nós do bioinvertidos pensamos que muitas pessoas acham a biologia desinteressante pelo modo que alguns foram apresentados a essa matéria. Queremos mostrar para vocês que não é sobre decorar nomes de estruturas e espécies, mas sim, sobre aprender a respeito da vida, de como ela funciona e como podemos conviver em harmonia com a natureza e as outras formas de vida que não estamos acostumados. E como pretendemos fazer isso? Relacionando essa parte mais abstrata do assunto com o cotidiano, incluindo curiosidades e tentando mostrar um pouquinho da mágica da biologia.

É isso aí pessoal, espero que tenham gostado! Ouçam nosso podcast quantas vezes quiserem, envie-nos suas perguntas por meio de nossas redes sociais, assim como sugestões de temas,

Até a próxima!

0 notes