#d a pennebaker

Photo

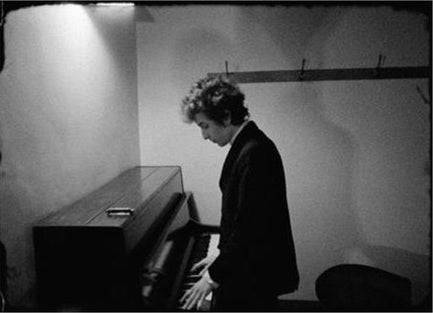

Original Cast Album: Company (1970), dir. D. A. Pennebaker

#steve looks so hot here its insane#original cast album company#stephen sondheim#*#d. a. pennebaker#d a pennebaker#film stills

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

D. A. Pennebaker, July 15, 1925 – August 1, 2019.

7 notes

·

View notes

Video

vimeo

Lecture 6: “Subterranean Homesick Blues” (1965): This tune, from Bob Dylan’s fifth studio album Bringing it All Back Home (1965), was his first Top 40 hit, reaching #39 on the Billboard 100. Dylan drew on influences from Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Chuck Berry, and the beat poet Jack Kerouac when writing “Subterranean Homesick Blues,” a song that alludes to contemporary issues such as the emerging counter-culture and civil rights. The early music video was also innovative, particularly Dylan’s use of giant cue cards. Fun fact: Beat poet and counter-cultural icon Allen Ginsberg (with the beard) can be seen in the background, to the left. This scene is a clip from the late, great D. A. Pennebaker‘s landmark rockumentary, Don’t Look Back (1967).

#Bob Dylan#folk rock#folk music#Subterranean Homesick Blues#1965#Allen Ginsberg#D. A. Pennebaker#Bringing it All Back Home (1965)#Don't Look Back (1967)#rockumentary

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Watched Today: Original Cast Album: Company (1970)

0 notes

Text

Town Bloody Hall (1979) | dir. Chris Hegedus, D. A. Pennebaker.

#1970s#germaine greer#films#*#directed by women#feminism#female directors#feminist movie#documentary film#60s 70s 80s 90s#70s movies#1970s movies#feminist#feminist film#screencaps#documentary#movies#vintage#quote#film quotes#movie quotes#radical feminism#radfem#radical feminist safe#radical feminist community#radical feminst#radblr#radical feminist theory#feminist media#radical feminists do interact

116 notes

·

View notes

Text

JANIS JOPLIN | Monterey Pop (1968) dir. D. A. Pennebaker

#janis joplin#my upload#1960s#60s#usermusic#musicdaily#tusercourtney#tuserchar#vintage#vintageedit#blogmusicdaily#nerd4music

66 notes

·

View notes

Text

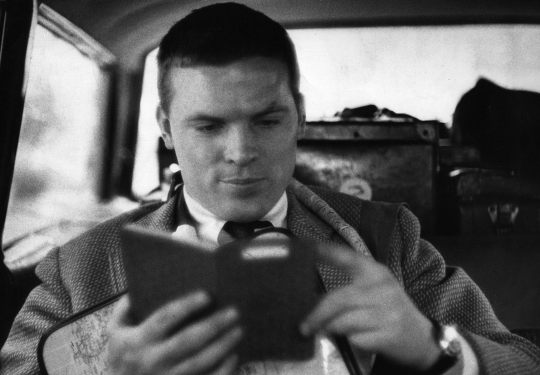

Daily Dylan 2023 - 343

By D A Pennebaker

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

After the Brian Matthew interview at the BBC [on May 2, 1966] Paul and John went to the nightclub Dolly’s at 57–58 Jermyn Street, accompanied by Neil Aspinall and Rolling Stones Keith Richards and Brian Jones. Already at the club was Bob Dylan, who’d arrived that afternoon from Copenhagen for a European tour that would start in Dublin on May 5. Later in the night all six men returned to Dylan’s suite at the Mayfair Hotel, where Paul and Dylan played pressings of their latest songs. The ace in Paul’s pack was “Tomorrow Never Knows,” proof, he thought, that the Beatles were at the experimental cutting edge of pop. Dylan didn’t show any emotion and then turned to him and said, “Oh, I get it. You don’t want to be cute anymore.”

This was a typical Dylan put-down of the period, implying that “cute” was all the Beatles had ever been and suggesting that “Tomorrow Never Knows” was a mere exercise in confounding expectations rather than a substantial change in their art. One of the few people to observe the dynamic in the relationship between the two musicians was director D. A. Pennebaker, who was filming the tour in the same way he’d filmed Dylan’s last UK tour for the documentary Don’t Look Back. In Pennebaker’s view Dylan didn’t really connect with Paul. Even though the two of them were talking in the same room, Dylan’s thoughts were always elsewhere.

[—from Beatles ’66: The Revolutionary Year, Steve Turner]

Dylan on Paul McCartney [interviewed on April 23, 1966]. “Like, man, he’s a great actor, interested in everything. He writes most of the Beatles’ songs.”

[—from “Dylan – man in a mask,” Rosemary Garrette, Canberra Times (May 7, 1966)]

#AAAAAA LOL#can't believe bob dylan just COULDN'T BEAR TO ADMIT TO PAUL'S FACE THAT HE THOUGHT HE WAS COOL#this is So Funny (presses hands to face)#truly australian newspapers are the gift that keeps on giving#bob dylan#paul mccartney#paul and bob dylan#beatles '66: the revolutionary year#steve turner#rosemary garette#the beatles#1966#newspaper

96 notes

·

View notes

Video

youtube

Being Alive - Company OBC, 1970 - Dean Jones

Original Cast Album: Company is a 1970 documentary film by D. A. Pennebaker, observing the marathon recording session to create the original cast album for the Stephen Sondheim musical Company. As Company continued its successful run on Broadway, the film was screened at the New York Film Festival in September 1970, unanimously praised by a crowd that filled the auditorium to capacity.

Filled with behind the scenes footage of the marathon recording process at the Columbia Records studio at East 30th Street and Third Avenue on the first Sunday in May, the film captures both the musical direction and insight of composer Sondheim. Several of Company songs appear in the film, including "Another Hundred People", "Getting Married Today", and "Being Alive"—all recorded with a live orchestra, done in multiple takes, over the course of a lengthy studio session.

After working in film and television, Dean Jones was set to return to Broadway as the star of Stephen Sondheim's musical Company in 1970. Shortly after opening night, he withdrew from the show, due to stress that he was undergoing from ongoing divorce proceedings. Director Harold Prince agreed to replace him with Larry Kert if Jones would open the show and record the cast album. He agreed, and his performance is preserved on the original cast album.

Shown here is Jones’s bravado performance singing the showstopper “Being Alive.”

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

(60)Psychology books

Meditations by Marcus Aurelius ✅

How to Analyze People with Dark Psychology

Reading People by Anne Bogel

How to Read People Like a Book

What Every Body Is Saying

The Secrets of Body Language

How To Analyze People

Read People Like a Book

Mindreader

You are not so smart

From the Diary of a Psychologist by Dr. Asha Dinesh

The Secret Life of Pronouns by James Pennebake

The Happiness Hypothesis by Jonathan Heidt

The Archetypes and The Collective Unconscious by Carl Jung

Sex at Dawn by Christopher Ryan

Man and His Symbols by Carl Jung

Memories, Dream, Reflections by Carl Jung

Wisdom of Psyche by Ginette Paris

Flow by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi

Beyond Good And Evil by Friedrich Nietzsche

Behave by Robert Sapolsky

Thinking Fast & Slow

48 Laws of Power by Robert Greene

The Wellness Sense by Om Swami

The Nocturnal Brain

7.5 lessons about the brain

Range: Why Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World

Man's Search for Meaning by Viktor E. Frankl

The Social Animal by David Brooks

Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion by Robert B. Cialdini

An Unquiet Mind: A Memoir of Moods and Madness by Kay Redfield Jamison

The Road Less Traveled: A New Psychology of Love, Traditional Values, and Spiritual Growth by M. Scott Peck

The Art of Loving by Erich Fromm

The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat and Other Clinical Tales by Oliver Sacks

Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ by Daniel Goleman

The Interpretation of Dreams by Sigmund Freud

Stumbling on Happiness by Daniel Gilbert

Theories of Personality by Calvin S. Hall and Gardner Lindzey

The New Psycho-Cybernetics by Maxwell Maltz

The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life by Richard J. Herrnstein and Charles Murray

The Body Keeps the Score: Brain, Mind, and Body in the Healing of Trauma by Bessel van der Kolk

The Psychopath Test: A Journey Through the Madness Industry by Jon Ronson

The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion by Jonathan Haidt

Maps of Meaning: The Architecture of Belief by Jordan B. Peterson

A First-Rate Madness: Uncovering the Links Between Leadership and Mental Illness by Nassir Ghaemi

The Feeling Good Handbook by David D. Burns

Thinking About Psychology: The Science of Mind and Behavior by Charles T. Blair-Broeker and Randal M. Emst

The Evolution of Cooperation by Robert Axelrod

The Handbook of Psychological Testing by Paul Kline

. The Nature of Prejudice by Gordon W. Allport

The Origins of Totalitarianism by Hannah Arendt

The Psychopathology of Everyday Life by Sigmund Freud

The Structure of Scientific Revolutions by Thomas S. Kuhn

The Principles of Psychology" by William James

An Unquiet Mind: A Memoir of Moods and Madness" by Kay Redfield Jamison

"The Noonday Demon: An Atlas of Depression" by Andrew Solomon

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders" (DSM-5) by the American Psychiatric Association

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

“until all women are lesbians there will be no true political revolution.” / reacting to jill johnston in town bloody hall (c. hegedus, d. a. pennebaker, 1979)

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

D. A. Pennebaker, July 15, 1925 – August 1, 2019.

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mississippi Masala: The Ocean of Comings and Goings

By Bilal Qureshi

MAY 25, 2022

often remark that my Punjabi parents immigrated to the American South woefully unaware that they’d brought us to a place with an incurable preexisting condition. Racism doesn’t belong exclusively to the South—the former Confederacy—but it was implemented at industrial scale across the region’s economic, political, and cultural life. Alongside this landscape’s sublime natural beauty—rivers, fields, and bayous—sits the history of America’s unsparing brutality against its Black citizens. On the other side of the world, in South Asia, as well as among its global diasporas, anti-Blackness is embedded in ideas of colorism and caste, in tribal imaginaries and policed lines of “suitable” marriages.

The possibility to live—and to love—across racial borders is the theme of Mira Nair’s extraordinarily prescient and sexy second feature film, Mississippi Masala (1991). Three decades later, it speaks to a new generation as groundbreaking filmic heritage—but also with an almost eerie, prophetic wisdom for how to live beyond the confinements of identity and color. Even by today’s standards, the film is a radical triumph of cinematic representation, centering as it does Black and Brown filmmaking, acting, and storytelling. It is also a genre-defying outlier that would likely be as difficult to get financed and produced today as it was then. Part comedy, part drama, rooted in memoir and colonial history, the film that Nair imagined was a low-budget independent one with global settings and ambitions. The notion of representation—perhaps more accurately described as a correction of earlier misrepresentations—wasn’t its point or its currency. Race was its very subject. Nair has said she wanted to confront the “hierarchy of color” in America, India, and East Africa with the film—the kinds of limitations that she had experienced firsthand by living, studying (first sociology, then film), and making documentaries in both India and the United States. In a shift that began with her first feature film, Salaam Bombay! (1988), Nair set out to transform those real-world issues into fictionalized worlds, translating her sociological observations into works suffused with beauty, music, and, in the case of Mississippi Masala, humid sensuality.

Nair first engaged with the questions at the heart of the film when she came to the United States from India to study at Harvard in the mid-1970s. As a new arrival to the country’s color line, she has recalled, both its Black and white communities were accessible to her, and yet she belonged to neither. The experience of being outside that specific American binary would be a formative and fertile site of dislocation for the young filmmaker. Nair trained in documentary under the mentorship of D. A. Pennebaker, among others, and her first films were immersive explorations of questions that haunted her own life. The pangs of exile and homesickness for lost motherlands became the foundation of So Far from India (1983), and the boundaries of “respectability” for women in Indian society the subject of India Cabaret (1985). Salaam Bombay!—made in collaboration with her fellow Indian-born classmate, the photographer and screenwriter Sooni Taraporevala—carried her Direct Cinema training to extraordinary new heights. Working, from a script by Taraporevala, with nonactors on location in the streets of Mumbai, Nair found a filmic language that could merge the rigor of realism with the haunting emotion of fiction. It would become the creative model for Nair and Taraporevala’s translation of the real-life phenomenon of Indian-owned motels in the American South into a spicy cinematic blend of migration, rebellion, and romance.

During research trips across Mississippi, Louisiana, and South Carolina that Nair made in 1989, she discovered that many of the Indian motel owners in the South had come to the United States from Uganda following their expulsion by President Idi Amin in 1972. Ten years after the East African country gained its independence from British rule, Amin had blamed his country’s economic woes on its privileged and financially successful South Asian community. In the racial politics of empire, the British had privileged the Indian workers they had imported to East Africa, creating racial hierarchies Amin now wanted to destroy by way of politicizing race anew. In a line that is repeated in the screenplay, the mission was “Africa for Africans,” and for tens of thousands of Asian families, it was an uprooting and dislocation from which some would never recover.

In Mississippi Masala, the classically trained British Indian actor Roshan Seth plays Jay, the immigrant father who is the focal point of the “past” of the film’s dual narrative, which is beautifully balanced in the way that it interweaves the perspectives of two generations. In the film’s harrowing overture, Jay—along with his wife, Kinnu (Sharmila Tagore), and their daughter, Mina (Sarita Choudhury)—is being forced to flee Kampala, and he laments that it will always be the only home he has known. With stoic reserve, holding back tears, Seth conveys the gravity of the loss, as the camera captures the lush beauty of the family’s garden and the faces of those they must leave behind. Throughout the film, as Kinnu, Tagore—an acclaimed Indian film star and frequent Satyajit Ray collaborator—is a composed counterpoint to Seth’s troubled Jay in her character’s strength and resilience. When the film picks up with the family two decades later, Kinnu is shown managing the family’s liquor store, while an aging Jay writes to petition Uganda’s new government to reclaim his lost property. Nair’s camera pans up from his writing desk to reveal through his window the parking lot of a roadside Mississippi motel. This is where Jay works and exists in a permanent state of nostalgia, until he is jolted awake by Mina’s demands for a home and a life of her own.

Even as Jay dreams in sepia-toned memories, the film itself never descends into saccharine longing or scored sentimentality. The rigor of the research and on-location filmmaking in both Mississippi and Kampala is reflected in an unvarnished and immersive visual style. While Nair herself clearly understood the fabric of the lives of the Gujarati Hindu families she was portraying, she has discussed how Denzel Washington became a critical collaborator in ensuring that southern Black life was rendered with equal attention to detail, cultural specificity, and dignity. The result is a film whose homes and communities are etched with a palpable sense of reality.

All of Mississippi Masala’s disparate threads are bound together by a distinctly sultry southern love story, which naturally remains the best-remembered feature of the film. The meet-cute of Mina and Washington’s character, Demetrius, is quite literally a traffic collision, a not-so-subtle suggestion that, without a bit of movie magic and melodrama, these two southerners might never have been maneuvered into the exchanged numbers and glances, and palpable wanting, that still burn the screen today. The film is fueled by the gorgeousness and megawatt charisma of both its stars, the young Washington paired with Choudhury in a prodigious debut as a woman at the edge of adulthood—her mane of wavy hair, their sweaty night of dancing to Keith Sweat, aimless late-night phone calls, dark skin in white bedsheets, secret meetings, consummated desires.

In the background of the R&B song of young, electric love are the film’s quieter, deeper notes on migration. A string leitmotif by the classical Indian violinist L. Subramaniam recurs whenever the vistas of Lake Victoria across the family’s lost garden in Kampala appear on-screen in brief flashbacks. Nair’s mastery with music has only deepened with time, resulting in films that integrate archival and original music with a free-form alertness that is distinctly her own. Both for the African American people living amid strip malls in the dilapidated neighborhoods of a region to which their ancestors were brought by bondage, and for the Indian families forced by Amin to flee their homes, exile is expressed in stereo. As Jay pines for the country he lost, Demetrius’s brother dreams of visiting Africa and saluting Nelson Mandela—disparate but recognizable longings and family histories shared over a southern barbecue, American bridges.

There wouldn’t be racial borders, however, if they weren’t policed, and the policing authorities here come from across the racial spectrum. When Mina and Demetrius’s relationship is discovered by nosy Indian uncles, those boundaries flare up. From the Black ex-girlfriend who asks why the good Black men can’t date Black women, to the Indian uncles who barge into Demetrius and Mina’s hotel room, to the gossiping aunties who during phone calls mock Mina’s rebellious scandal, there is a veritable chorus of condemnation. It is portrayed with great comedic timing and wit, including from Nair herself, who delivers some of the sharpest lines of disapproval in the role of “Gossip 1.” But the implications of those judgments remain unfunny by design. The film’s remarkable achievement is the way it never buckles under the thematic weight of these uncomfortable truths. Nair always delivers her cerebral punches with a lightness and warmth that are precisely calibrated. These are the markers of a filmmaker in full control of the tone, color, production design, and, always, music to accompany the emotional demands of her material, and that facility has only gotten sharper in such masterpieces as Monsoon Wedding (2001).

Mississippi Masala showed at festivals in late 1991 and was released commercially in American cinemas in February 1992, within weeks of Wayne’s World and Basic Instinct. Working outside Hollywood’s conventions, Nair joined an extraordinary flowering in independent filmmaking that continues to be celebrated. The year 1991 had been a landmark one for Black cinema already, with the release of Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust, Mario Van Peebles’s New Jack City, and John Singleton’s Boyz n the Hood. Spike Lee’s opus Malcolm X, with Washington in the title role, would be released in the U.S. in late 1992. Nair’s film was shown at the same 1992 Sundance Film Festival at which a landmark panel about LGBTQ representation heralded a movement, named New Queer Cinema by moderator B. Ruby Rich, devoted to reclaiming stories of love and suffering from Hollywood’s gaze. These were parallel currents that echoed larger shifts and openings happening in global culture. The collapse of the Soviet Union, the end of apartheid in South Africa, India’s economic liberalization, and the rise of a youthful southern Democrat in the U.S. following a decade of Republican rule were stirrings of a new order. The possibilities were being felt all over the world as Nair’s film of southern futures arrived.

Described by the New York Times at the time as “sweetly pungent” and by the Washington Post as a “savory multiracial stew,” Mississippi Masala opened in American cinemas to rave, if exoticizing, reviews, less than a decade after Richard Attenborough’s Gandhi and Steven Spielberg’s portrayal of Indian characters eating monkey brains during a ritual dinner in Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom. Realistic international cinema featuring everyday South Asian life—as opposed to the Indian musical tradition or Hollywood’s tropes about foreignness—had almost no precedents or peers at the time. The depiction of South Asian characters as ordinary working-class Americans navigating questions of family, money, and love remains a radical achievement. Mississippi Masala also manages to decenter whiteness altogether. In a film about racial hierarchies, white characters appear only in the background, as the motel guests, patrons, and shopkeepers of Greenwood society. By design, this is first and foremost a film about Mina and Demetrius, and the families and communities that formed them.

Despite all the extraordinary accomplishments in the streaming age by the current generation of filmmakers of color, Mississippi Masala’s layered portrayal of race and love still feels unparalleled. To hear its characters speak candidly about the real lines that divide them, and reflect on the costs of crossing those lines, is to recognize the rigorous thinking—and living—that informed the screenplay. Even more disappointing than the lack of contemporary equals to the film, perhaps, are the offscreen parallels in South Asian communities like my own, where colorism and anti-Blackness are stubborn traditions yet to be fully dismantled. Stories of interracial love are still rarely told on-screen, and these relationships—the masala mixes—are still not visible enough to become as normalized as they deserve to be.

One of Nair’s first films, So Far from India, was filmed between New York City and Gujarat. It opens with a folk musician in the streets of Ahmedabad, a sequence that serves as a prelude to the film, about an Indian immigrant and the wife he has left behind. Nair, as narrator, translates his singing about the ocean of comings and goings. With Mississippi Masala, Nair positioned herself as both a great chronicler and a great navigator of that vast ocean of comings and goings. America is one of Nair’s homes, and she has made several films about the immigrant experience there, including her adaptations of Jhumpa Lahiri’s The Namesake (2006) and Mohsin Hamid’s The Reluctant Fundamentalist (2012). Each has sought to look at the country through the eyes of those usually on the margins in order to dramatize and problematize the idea of the American dream. It is these poetic and cinematic ruminations on identities in flux that feel like her most enduring, almost personal, gifts to hyphenated viewers like myself.

When I was younger, I thought Mississippi Masala embodied Mina’s rebellion, the promise of independence, and the freedom to choose whom and how to love. But now, twenty years after I first saw the film, at university, Jay’s longing for home and his incurable displacement feel equally, achingly resonant. With the limitations of America laid bare by the gift of adulthood, migration is no longer only a hurtling forward toward the rush of freedoms; it is now also the unknowable costs borne by my parents, the homes and selves they left behind.

The film’s closing credits, braiding Jay’s return to Kampala with glimpses of Mina and Demetrius kissing in the warmth of the southern sun, capture Nair’s exquisite feat of balancing—and blending—in Mississippi Masala. For a film traversing so many geographies and registers, there is finally a seamless harmony between father and daughter, between tradition and future, between here and there. As seen anew in restored colors, Mississippi Masala endures not for its spicy and pungent aromas of cultural specificity or representational breakthrough but for this profound commitment to multiplicity. It is a timeless song for and to those who live—and love—in multitudes.

#Criterion Collection#Mississippi Masala#Mira Nair#Charles S. Dutton#Denzel Washington#Roshan Seth#Sarita Choudhury#Sharmila Tagore#Joe Seneca#Bilal Qureshi

0 notes

Text

-- > Don't Look Back (1967) < --

de D. A. Pennebaker (UK)

Qué onda Dont Look Back?

Retrato de la gira de Bob Dylan por Inglaterra en 1965.

Muchas veces los mejores documentales son simplemente aquellos en los que pones a alguien con una cámara y una buena mirada a capturar momentos.

En esta gira, se nos muestra principalmente a Dylan atendiendo a la prensa, sacándola a pasear por las burradas que tiene que fumarse constantemente...

Lo vas a ver ranchear con sus amistades en los hoteles, en los camarines, siempre tocando, cantando, riendo, bebiendo, fumando y escribiendo. Están Joan Baez, Robbie Robertson, Donovan, el mánager y más...

Pobre Donovan la liga también...

Pasa que desde el vamos, la prensa lo comparaba con Dylan... Y el director decide retratar la enorme distancia de vuelo literario que hay entre ellos...quedando así, pobrecito Donovan, opacado.

Como la temática "Letras" es muy importante en esta película, me tomé el trabajo de traducirlas para ustedes.

*Importante*: todo esto transcurre en un momento crucial en la carrera de Dylan, que es cuando es fuertemente criticado por alejarse de las canciones de protesta, para cantar otro tipo de historias, tocar con banda y guitarra eléctrica...

Si siempre te interesó el universo Dylan pero te dio paja, este documental es para vos.

En lo personal le tengo mucho cariño a esta película, porque fue parte de algo más grande en mi vida con lo que me formé. Espero poder transmitirles algo, aunque sea una pequeña parte de todo eso.

0 notes

Text

Documentary in a shifting landscape

Grace Doyle

Salesman

America was in turmoil entering the 1960s. The threat of nuclear war still loomed large, and there was an overall loss of confidence in social institutions when compared to pre-War American society. The film industry itself was in the process of being dismantled from its then-monopolistic structure. As a result, documentary filmmaking emerged as a response, and a way for filmmakers to target these institutions more intimately. The Maysles Brothers, whose initial claim to fame came from shooting celebrities like the Beatles and Joseph Levine, shifted their attention to a group which was more grounded in reality: thus, Salesman (1969) was created.

Salesman follows the excursions of four door-to-door Bible salesmen in middle class America. The group travels from Boston to Florida as they try to sell their books to lower-income Catholics. Both the merchants and the customers are struggling to make ends meet, which results in low income for the men. Struggling most is Paul, who tries and fails multiple times at a simple sale. However, the majority of the people they interact with are housewives and the elderly, each with their own issues.

The cinema vérité style which is present in the film forces the film to be observational in its depictions of middle-class citizens across America. In my initial viewing, I imagined it would be a commentary on the church and religion as an industry, but as I came to find out, it was more of a critique of capitalism in the 1960s, and how there are no true winners when pursuing the unattainable American Dream.

Dont Look Back

Dont Look Back (1967) follows folk singer Bob Dylan during his U.K. tour in 1965. Dylan’s iconography sometimes precedes him in modern day: either, he is held to the highest regard as a poet and a preacher, or he is mocked for his pretentious nature. This film depicts an accurate portrait of each of those sentiments. Dylan’s obvious social intelligence often conflicts with his ego, and his abrasive nature clouds his often progressive views about social issues and human nature. As described by Richard Porton, “Whether Dylan is mocking the inane questions posed to him by hack journalists, engaging in what Robert Polito terms a ‘venomous pissing contest’ with pop star Donovan, or casually paving the way for a breakup with then-girlfriend Joan Baez, he is never, even though he’s alternatively charming and nasty, anything less than a charismatic presence,” (Porton, 24).

This film, also shot in the cinema vérité style, allows viewers an unobstructed portrayal of the youth’s mindset in the mid-1960s. Dylan and Baez were the faces of the folk-revival movement, and their poetry reflected the turning of the political tides. Followers of the rising counterculture movement, like Dylan, questioned authority and were suspicious of industries like the government and the media. Dylan never wanted to be a savior; yet, voicing his political views with such integrity and determination garnered him a following. Dont Look Back is, at its core, a commentary on the politics of the entertainment industry.

Works Cited

Haleff, Maxine. “The Maysles Brothers and ‘Direct Cinema.’” Film Comment, vol. 2, no. 2, 1964, pp. 19–23. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/43754339. Accessed 4 Dec. 2023.

Pennebaker, D. A., et al. “The View From Backstage: An Interview With D. A. Pennebaker and Chris Hegedus.” Cinéaste, vol. 41, no. 3, 2016, pp. 24–33. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/26356423. Accessed 4 Dec. 2023.

0 notes