#d'var

Text

Thursday Thoughts: Structure, Flexibility, and Torah

(I wrote this d’var for tomorrow’s Shabbat evening services. Turns out I won’t be leading services tomorrow after all - so I’m sharing it here instead!)

I love being a Jew. I see it as an active thing – BEING a Jew. Living a Jewish life, making Jewish choices, taking part in our rich, meaningful traditions and fulfilling the mitzvot of the Torah.

However, if I said that I was living a Jewish life in every possible way – making all Jewish choices, taking part in all our traditions, and fulfilling all mitzvot – that would be a lie.

Those of you who come to Shabbat services regularly on Friday nights know that you will nearly always find me here, now. However, if you also come on Saturday morning, then you know that you will almost never find me there, then. I bake challah, but I do not light Shabbat candles. I take time off from my day job on Jewish holidays when I can, but I’m not always able to. I eat kosher foods, but I do not have kosher dishes, since I share my kitchen with three people who do not keep kosher.

I do what I can. Sometimes, I feel like I’m not doing enough.

It’s easy to imagine that G-d might also think that I’m not doing enough. After all, there are 613 mitzvot in the Torah. If your boss gave you an employee handbook with 613 rules for employee conduct, then you would assume that this is a strict boss with a very structured work environment, someone who wants you to obey their instructions without fail or flexibility.

But this week’s parsha makes it clear that “obey without fail or flexibility” is not an entirely accurate description of G-d’s expectations for Jewish people.

This week we read Parshat Vayikra – the beginning of the book of Leviticus. Incidentally, Leviticus has 243 of the 613 mitzvot – more than any other book in the Torah.

(If you’re curious, second place goes to Deuteronomy at 203 mitzvot, Exodus comes in third at 109, Numbers is fourth at 56, and Genesis has only two.)

So, Leviticus is the Big Book of Rules, right? In Vayikra, the start of this book, there are a lot of rules about making offerings at the temple. These are sin offerings. A person would admit wrongdoing and atone for their sin by making the offering. In Leviticus chapter 5 verse 6, the Torah explains, “he shall bring his guilt offering to the Lord for his sin which he had committed, a female from the flock, either a sheep or a goat, for a sin offering.”

But it doesn’t end there. The next verse, verse 7, reads “But if he cannot afford a sheep, he shall bring as his guilt offering for that [sin] that he had committed, two turtle doves or two young doves before the Lord.”

And then if we jump ahead a couple verses, to verse 11, the Torah reads, “But if he cannot afford two turtle doves or two young doves, then he shall bring as his sacrifice for his sin one tenth of an ephah of fine flour for a sin offering.”

(An ephah is a unit of measurement here, and according to Google, it’s about the size of a bushel. So you would bring a tenth of a bushel of flour. I’m not sure exactly how big that is, but it doesn’t sound like much. Certainly it sounds less than a whole sheep.)

So – the commandment here, the mitzvah, is to make a sin offering. And through the Torah, G-d gives specific instructions about what to bring and what to do with it – you bring a sheep, and this is how you kill it. It’s a structure for atonement. But the Torah also provides exceptions or alternate options for this sin offering. If you can’t bring a sheep, bring two doves, and if you can’t bring two doves, bring some flour. The Torah provides structure, and it also provides different structures depending on your individual means.

In doing so, the Torah takes a behavior that could be very limited – something that only rich people could do, the people who could afford to give up an animal because they had plenty more to eat or breed – and turns it into something that anyone could do, within their means, in the way that works best for them. It’s flexible. It’s also encouraging in a way – having these different options for how to participate in the mitzvah makes the whole idea of making sin offerings feel more accessible for anyone.

And this ties in well with how I see and experience Judaism. It’s accessible for all of us. Yes, there’s structure. Judaism includes instructions for every part of our lives. And like I said before, it’s an active thing. I don’t think that you can really BE a Jew if you aren’t doing ANYTHING that’s Jewish.

But you don’t need to do EVERYTHING.

You don’t need to obey EVERY commandment in exactly the same way as everyone else in order to live a Jewish life, make Jewish choices, and participate in the Jewish community. G-d empowers all of us to show up when we can, and how we can, in the way that works best for us, to create a meaningful life as Jews. For me, tonight, that means standing up here in front of you, delivering this d’var. Last week, it meant sitting in the back row with my friends, and next week, it will mean traveling home to spend Passover with my family. And every week, every day, we get to make those Jewish choices, to create our Jewish life. Shabbat shalom.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

free my girl she's a gorgeously complicated and immensely well written character but people refuse to analyze her beyond 'girlboss lol'

#the imaginary fandom in my head has now created conflict amongst itself#d'var#female characters#fandom culture#why does fandom hate women#oc lore#asta discusses#shitposting

1 note

·

View note

Note

Wait can you tell us about the sea of reeds? That sounds fascinating

Sure!

In this post, I mentioned that the crossing of the Sea of Reeds (Chapter 14 of Exodus/Shemot) evokes birth imagery. Here is an excerpt from Exodus 14:21-14:22: "Thus the waters split. The Children of Israel came through the midst of the sea upon the dry-land, the waters a wall for them on their right and on their left."

In these verses, the people of Israel are specifically called the children of Israel. That word choice, on its own, isn't terribly significant. "Children of Israel" is a common phrase in the Torah. The Israelite people are descended from a man named Israel and therefore are literally children of Israel. The phrase also implicitly casts God as a parent protecting God's own children.

The surrounding context, however, suggests that "children" has an additional meaning here. In Hebrew, Egypt is called Mitzrayim: literally, "the narrow place." Scholars have written hundreds of pages on the meaning of this term, but for now, I want to take it fairly literally. The Children of Israel are moving from a narrow place, through walls of water, into a new life. That sounds an awful lot like an infant moving out of the constriction of the womb, through the breaking "water" of amniotic fluid, and being born.

Even Moses seems to pick up on the metaphor. In Numbers 11:12, he sarcastically asks God, "Did I myself conceive this entire people, or did I myself give birth to it?" God doesn't answer the question directly. Instead, God reminds Moses of his responsibility towards the Israelites and encourages him to seek out people who can help him. The implied answer is "Yes, actually, you and I did birth these people, and we are therefore responsible for taking care of them."

Why would crossing the Sea of Reeds be compared to birth? Well, the podcast Judaism Unbound offers an answer. In the podcast, the hosts describe two systems for thinking about Jewish identity: Genesis Jews and Exodus Jews.

For Genesis Jews, all Jews are members of an extended family united by common ancestry. Their model is Abraham and his descendants in Genesis. Exodus Jews, by contrast, are Jews because of shared experiences. Their model is the exodus from Egypt, through which the Children of Israel and the mixed multitude accompanying them became an entirely new people. They went from being slaves to being an independent, cohesive ethnic group ready to forge a brand new society.

In other words: the moment in which the Children of Israel crossed the Sea of Reeds was the moment in which they were truly born.

Citations: All scriptural quotes come from the Everett Fox translation of the Five Books of Moses. The first four episodes of the podcast Judaism Unbound cover the concepts of Genesis Jews vs. Exodus Jews, although the hosts repeatedly revisit the topic in subsequent episodes.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

I'm so tired but I'm too freaked out to go back to sleep so instead I'm going to get ready and go to synagogue this morning. I can nap after services.

#text post#my post#my anxiety about everything is worst at night and early in the morning#but my meeting with the rabbi was good and services last night were good and services this morning will be good#plus someone's have her bat mitzvah this morning and it's the same parsha from my bat mitzvah 12 years ago#so it'll be fun to hear her d'var torah and think back to mine

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

parshat chayei sarah tells us not to give into despair and to maintain our revolutionary optimism

0 notes

Text

youtube

The Chief Rabbi's D'var Torah for Pekudei.

Chief Rabbi Ephraim Mirvis

16 notes

·

View notes

Note

For bar/bat mitzvahs, do they start at a synagogue and the child reads something from the Torah and then everyone goes to the child’s house afterwards for the birthday party portion? Are outsiders like non Jewish family or friends allowed to attend the religious aspect and sit in on the synagogue reading or is it a more private affair? I guess I have a lot of questions about the religious aspect. I’m trying to include Jewish representation in a story and I don’t want to portray it as just some big birthday when it’s more significant than that. I’ve also heard that sometime instead of reading from the Torah they recite a prayer instead? What are some common prayers or passages from the Torah that are read in your opinion?

I should state I'm not a Rabbi nor a particularly religious person.

If someone is writing a Jewish character or Jewish scene it's first important to understand what kind of Jew are you writing? the mood vibe and style of Orthodox, Conservative and Reform (the big 3) are different and thats before you get into like Hassidic or Reconstructionist. And of course Ashkenazi and Sephardi are different liturgical traditions

So speaking as a not very observant Reformnik, the way it was for me, generally speaking its fine for non-Jewish friends to come to Synagogue, that said it was like, you invited your *real* friends to the service and like all the people you want at your party can come to the party.

any ways yes it generally starts at synagogue, I had to read from the Torah, and then give whats called a D'var Torah, which basically is explaining what it is you read and what it means and you're trying to make an original point (rather hard to do with a 3,000 year old document) and a "lesson" to the congregation. This I believe is usual, but I hear some kids don't have to read from the Torah and only have to do the blessings, lucky them. You don't get to pick, Jews read a Torah portion same day every year, we have a holiday when we've finished (And start again) so the Bar mitzvah kid is assigned that week's reading

oh reading the Torah is called Aliyah, means "going up".

and then yes you go to the party after Synagogue, some kids like have a party RIGHT after, some its like you do the synagogue thing in the morning and the party is at night, you know generally there's not a birthday cake as a rule lol and all the food is kosher

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Another Song (and Some Dark Thoughts)

Dear Future Husband,

My last post was about this song L'man Achai by The Chevra, but that's not the only song that I listened to over Chanukah that ended up as an earworm for me. One of the other songs that's been kicking around my brain, one which wasn't as much on the forefront of my mind as L'man Achai, but which has still bobbed to the top on occasion, is the Six13 acapella version of L'Cha Dodi.

My brain tends to pick certain lines of a song and just repeat those over and over (surprisingly not always the chorus), so I rarely have the whole song on repeat in my head, and instead it's just a few bars.

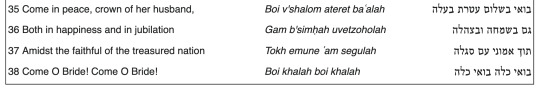

And this time the part on repeat was primarily the end of the zemer:

So the line "Toch emunei am segulah" has been floating around my brain for a couple of weeks. And again, my Hebrew skills aren't that amazing, so I'm pretty bad at knowing the translations of the songs that I sing unless I think reeally hard about them. And I didn't really think too much about what this whole zemer means.

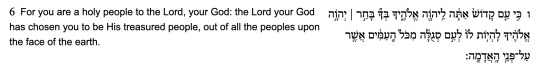

But I was just on a forum reading about the Jews as the "chosen people" and it occurred to me I don't know where that reference actually comes from. So I went to chatgpt and asked for the source (viewable here), which is apparently from Devarim 7:6.

I tried Sefaria, but I think chabad.org has the better translation for this passuk. (Although you can see some consistencies in the various translation options on Sefaria)

The word used for "chosen" appears to be bachor which usually refers to an oldest son who is given the choice portion of an inheritance. Which in this case would refer to the fact that every nation of people on planet earth are God's children and are all loved by Him, regardless of race, gender, religious affiliation, etc, and that the Jewish people are just the "oldest", the ones who are supposed to lead and teach the rest of the world, and with that responsibility comes additional requirements, and thus additional rewards.

I could go into a whole d'var torah about that, but that's not really what interested me...

What interested me, in case you didn't catch it already, is the reference to "Am Segulah" (His "treasured nation") in both places.

We don't really use that term often and it just kind of struck me while reading this passage that this portion that defines the Jews as "chosen" also uses the same term that has been bopping around my head for a couple of weeks.

Off the top of my head I couldn't have told you that segulah meant 'treasure', because we tend to use that term when we refer to a good luck charm (for lack of a better term), which I guess could be equated to a treasure if you think about it like that?

But usually treasure is something unrelated to luck. It's gold and diamonds and anything a dragon would hoard. Or it's sentimental, a memorial to something special with personal significance. To treasure something is to love it and protect it and keep it safe.

According to the wikipedia page for segulah, it's a charm or ritual in kabbalistic practice intended for protection or benevolence. Although over time a lot of kabbalistic practices have kind of become enmeshed with mainstream orthodox Jewish practice, so a lot of these "segulot" are accepted in general orthodox Jewish society without knowledge of their kabbalistic origins. Some refer to these as old wives tales and say to stop attempting these "extra credit projects" and just do the "required assignments" of proper Torah adherence if you want the benefits that are supposedly "guaranteed" by the segulot...

Kabbalah really became a thing during the Middle Ages (aka The Dark Ages), which was fraught with darkness and evil and superstition. Stories like the Grimm Brothers Fairy Tales and our own stories of the Golem originate from these times. It was also an era of mass death, whether inflicted by disease or humans. There was so much hatred and persecution towards various groups, but most especially Jews, who were kicked out of so many countries across Europe, that it makes sense that people would have wanted anything of protection and comfort to hold onto in those dark times.

But most of these modern segulot aren't amulets, they're not technically treasured artifacts, they're more ritualistic. For example:

People pray at the Kotel for 40 consecutive days as a segulah.

People take challah as a segulah.

People drink from the kos shel bracha at a wedding as a segulah.

People recite the entire sefer of tehillem as a segulah.

Etc.

So when I was "translating" the words in my head, trying to figure out what I was singing, "Am Segulah" never translated to 'treasured nation' or 'treasured people,' because that wasn't my association with the word 'segulah.'

And I'm kind of curious if we truly see ourselves as an "Am Segulah".

Do we view ourselves as something to be treasured?

Do we view ourselves as a group that deserves Divine protection and love and care?

I know that I personally don't.

Nothing about my life thus far has even hinted to me that I'm truly loved or cared for or treasured by humans OR God.

And I look around at all the awfulness that has happened to the Jews over the last 3000 years and I wonder how we lose our way so quickly in practically every generation.

Is it a self fulfilling prophesy?

Like in the story of Yoseph haTzaddik that we've been discussing in recent parshios - he told his family his dreams about them all bowing to him and THEY interpreted it as them treating him like a king. If they hadn't interpreted it that way or if he hadn't shared the dreams with them at all, would they have gotten mad at him and tried to get rid of him? Would the famine in Egypt have happened at all? Would Klal Yisrael have ever ended up in slavery in Mitzrayim?

How much of what we go through is predetermined and how much of it is the consequence of our own individual and collective actions?

For the majority of the Shabbossim over the last year I've spent time reading Jewish history books, most of which is stories or overviews of particular Rabbis from various eras, but the rest of it is just one horrid story after another. More in-fighting, more persecution, more exile. It's a never ending cycle that we just can't seem to break.

One story that continuously sticks out in my mind since reading about it earlier this year is the accounts of what happened in Eretz Yisrael globally and Yerushalayim specifically during the Chorban Bayis Sheini. It is absolutely horrific.

In elementary and middle school they dumb stuff down for us, so we end up with the childhood song lyrics that stick with us into adulthood that warp our ideas of the entire situation. Lyrics like:

(TOGETHER BY ABIE ROTENBERG)

I am an ancient wall of stone, atop a hill so high.

And if you listen with your heart, you just may hear my cry.

Where has the Bais Hamikdash gone, I stand here all alone.

How long am I to wait for all my children to come home?

A house of marble and of gold once stood here by my side.

From far and wide all came to see its beauty and its pride.

But Sin’as Chinam brought it down, and with it so much pain.

Now only Ahavas Yisroel can build it once again.

CHORUS 1:

Together, together, you stood by Har Sinai, my daughters and sons.

Forever, forever, you must stand together forever as one.

And with this "romantic" version of the Kotel longing for a Bais Hamikdash we can't relate to, destroyed in a time and controversy we don't understand, we have absolutely no idea how horrific the actual circumstances were because nobody speaks about it.

"But Sinas Chinam brought it down"

Do we even know what that means?

We come up with so many of our own contemporary examples but those are seriously watered down versions of the appalling and gruesome things that were happening that caused the complete destruction of the Bais Hamikdash.

I'm 35 years old. I've been through orthodox Jewish day schools and I've been to seminary.

And never once did I hear anyone discuss it, even when we visited locations like Massada.

Nobody wants to address the harsh realities.

But how are we supposed to recognize the deeply rooted problems in order to fix them if nobody is willing to talk about it?

Rabbi Berel Wein and Rabbi David Fohrman are two of the few Rabbis I've seen discuss any of this darkness.

Rabbi Wein discusses it in his 1990s book trilogy on Jewish history. Most of Jewish history happens against a complex and continuously active and morphing secular political background, but Jews turning against Jews in the streets outside the Bais Hamikdash was OUR fault.

It was US vs US.

The streets of Yerushalayim ran red as Jewish people slaughtered each other in cold blood over disagreements. All while daily karbanos were still being accepted by Hashem in the Bais Hamikdash.

We literally can't wrap our heads around what that means.

We don't understand what it means to truly despise each other that much over nothing.

We've just exited Chanukah and it's a celebration that isn't taught in full context either.

Whenever we discussed Chanukah in grade school and even in seminary, we never went into deep discussions about the war that was being fought by the Macabees. Everything taught about the story of Chanukah was just so superficial, which is crazy because there's so much more context and nuance that lends insight into who we are as a people and what it means to survive, all of which is never really touched on.

Chanukah was not the end of the war. It was a miraculous respite in the form of a won battle and a small jar of oil. But it was not a won war.

The Bais Hamikdash still stood during the Chanukah story, but it doesn't anymore. The end of that story was not a positive one.

We annually celebrate a momentary victory of such "minor" proportions that the holiday wasn't even instituted until a year after it occurred because the leaders of the time weren't even sure what to make of it right away.

But nobody talks about how and why the Hasmonean dynasty (the Macabee family) died out and has no descendants alive today. One of the descendants became the Kohen Gadol and literally imprisoned and murdered his own family members, including his mother. (I highly recommend the Aleph Beta videos for insight into this with a positive conclusion).

We all just want to white wash history into an "everyone hates the Jews, but we didn't do anything wrong" narrative and that's just not true. We are constantly doing wrong. That's why we haven't earned the 3rd and final Bais Hamikdash yet.

And I've been raised by pessimistic people who suffer from anxiety and depression that has been coded into their DNA by previous generations who suffered from anxiety and depression, and so my outlook has always been more negative and I tend to focus on the negative more often than I should.

And this means that when I talk to friends who have experienced something negative in the frum world or I read accounts online, whether it's here on tumblr or in a frum group on facebook, and when I see some of the disgusting comments left by people who don't care that their name and their family members' names will forever be associated with that comment, I immediately think "well, color me unsurprised. it's cuz we're all horrible failures who treat each other like garbage. we are undeserving of anything good. why are we even here?"

So I'm rarely emotionally effected by this stuff because it just seems unfortunately "normal" to me. And reading these historic accounts and seeing how awful we've been to each other for millennia.... I'm just continually unsurprised by the negative things that result here in the modern world.

I think that's one of the reasons I've been so "unaffected" by this war.

Because in my mind it's "of course this is happening. we've grown too comfortable, too complacent. and that complacency leads to us treating each other like trash, which leads to yet another pogrom."

Because "when the yidden don't make kiddush, the goyim make havdalah."

It happened in Mitzrayim.

It happened in Shushan.

It happened in Germany.

We like to say "never again" in reference to the Holocaust, but what are we saying?

It seems like more often than not we're saying "we won't let the goyim kill our people" but we have no control over that.

Hashem does.

The only things we have control over are our own actions. And our own actions, when focused on the things we're supposed to be doing, are what will prevent the goyim from killing us.

But it always starts with us.

And I'm trying, dear Future Husband. I'm really trying.

I know most of what I do is wrong. And I'm trying to correct myself. I'm often so stuck inside my own head that my constant failures are all I can think about and it makes positive change harder than pushing a boulder up a steep hill, but I'm trying.

I visited Israel for a short time earlier this year for the first time since seminary and I got pushback from pretty much everyone I spoke to when I told them that, despite having plans to stay in a city outside of Yerushalayim which I had to catch a bus for, and shlepping huge bags with me, I wanted to visit the Kosel first thing.

"You can do that later in the week when you're settled."

"You'll end up missing your bus if you're shlepping all over Yerushalayim when you get in."

But it was important to me and I couldn't understand how it wasn't important to everyone else.

Upon entering the land that even Moshe Rabbeinu didn't have the privilege to step foot in, how could the Kosel - the location of the greatest tragedies in Jewish history, and the holiest place on earth - not be my first stop??

How could tearing kriyah not be the first thing I do?

In fact, when I told people I needed to go and tear kriyah, some of them even asked "oh, you do that?" as though it's not an accepted thing to tear kriyah at the site of ultimate sadness in Jewish life and history. Some people told me I should wait until rosh chodesh so I wouldn't have to tear, because "loophole!"

To me, not visiting the Kosel first thing would be like being away from your parents' house for decades and then coming to stay in your old bedroom without saying hello to them first. Such a slap in the face. (And this is coming from someone who grew up in a family steeped in dysfunction and doesn't speak to her father...)

But so many people wanted me to push it off because it would be "an inconvenience."

THAT is what I mean when I say we are complacent.

THAT is what I mean when I say we are too comfortable.

I know so many people who live in Yerushalayim and when I was there and asked some of them the last time they visited the Kosel, I got numbers ranging from weeks to months. (A few said days, but not most).

Because "life gets in the way" and "we get busy."

And I know I'm not perfect in any way, shape, or form, but that honestly blew my mind and made me feel differently about everyone, and not in a good way.

Which just reinforces my negativity, which is even more problematic...

But I keep trying anyway.

How I wish Hashem would speak to me more clearly than the cryptic messages He sends me like this odd "coincidence" of the term "Am Segulah". Because I don't know what this message means.

Maybe it's a nod to the idea that we are cherished despite not feeling like we are. Maybe it's a message to tell me that I need to think more positively. Or maybe it's something else that I won't understand until the day that I die. I have no idea.

Regardless, wherever you are, I hope that you are trying too.

Because these are trying times. And all we can do is try.

-LivelyHeart

#jumblr#frumblr#shidduch#frum#jewish dating#orthodox#shadchanim#shidduchim#jewish#shadchan#shidduch dating#dating#jewishdating#i am the shidduch crisis

2 notes

·

View notes

Note

📼

Send 📼 to see an early childhood memory of my muse’s | Accepting

Dad decided Steven needed a break from studying for his bar mitzvah. What better way than to go see 'Empire' in theatres? As if to make up for being away for work, he held up two theatre tickets. He shuts his books and runs over to give him a hug. Dad holds him closer than usual.

(Rand's over at 'Uncle' Bernard's, Dad's best friend and chevruta, house. Mom's been buried for years.)

It's not quite the same as the beloved tapes they have at home. It is the first time he's seen it on the silver screen. Thoughts of summarizing the Song of the Sea for the D'var Torah, pointing out how there's still meaning now, and the trope are set aside when the lights go down, own personal bag of buttered popcorn on his lap.

He makes it a double feature. How did he get away with that?

#asked and answered#headcanons#grant | gentle dr jones#//AKA 'examples Steven knows to be real about his childhood'#//'where's Rand?' was the biggest ??? of the Lemire run

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thursday Thoughts: A Double Portion

[I will be reading this d’var at my synagogue tomorrow night!]

This week’s Torah portion is Chukat-Balak, which is actually two Torah portions. And that’s the first thing that caught my attention this week – some years, we read Chukat one week and Balak the next, and other years, we read them together. Why do we do this?

I did some research, and Chabad.org explains it like this. The Torah is split into 54 portions, or parshiyot. But there are only 50 or 51 Shabbats in a year, depending on if it’s a leap year, and there are also times when Jewish holidays coincide with Shabbat, and these holidays have special readings which replace the regular weekly Torah portion. So in any given year, we only have 48 weeks at the most in which to read 54 parshiyot. So to make sure that we read the entire Torah in a year, sometimes we need to combine Torah portions.

There are 14 parshiyot which can be paired together. Chukat and Balak are two of them. So that explains the technical reason why we read these two parshiyot together. But does this affect the WAY we read Chukat and Balak? Does reading these parshiyot together affect the way we INTERPRET what we read?

I believe it does. A lot happens in Chukat and Balak, and I believe that putting these two portions together encourages us to think about how all of the events fit together. So tonight, I’m not going to focus on one moment in Chukat-Balak. Instead, let’s go over the highlights and see what we discover.

Here are the highlights of Chukat: Miriam dies, Aaron dies, and Moses (after hitting a rock) is told by G-d that he will not lead the Children of Israel into the Promised Land. And then in Balak, a king named Balak summons the prophet Balaam to curse the Children of Israel, but instead, Balaam blesses the Children of Israel three times.

There’s a lot going on here! In Chukat, we see the three leaders of the Children of Israel, the siblings who together freed our ancestors from slavery, brought them out of Egypt, and have taken care of them since then – we lose two of them in quick succession, and we learn that soon the Children of Israel will lose Moses, too. Viewed on its own, Chukat is a sad story. At the end, we’re left wondering, what’s next for the Children of Israel? What will happen to them, without their leaders to protect them?

But then we read Balak, and I should point out that in parshat Balak, Moses is barely even mentioned. The Children of Israel don’t seem to have a leader to guide them. But when Balaam is ordered to curse the Children of Israel, G-d makes sure that Balaam blesses them instead. And this happens three times, and I can’t help but draw a parallel here – three blessings in Balak, for three lost leaders in Chukat.

So when we pair Balak with Chukat and read these parshiyot together, we get the answer to the question. The Children of Israel are losing their leaders, the three pillars of stability who have guided them since the book of Exodus. But G-d is still with them. They still receive blessings. Even without the intervention of the leaders they have relied on, things can still work out – and this is true for us today.

Individual leaders will come and go, and we will depend on each in their time, and we respect and appreciate their guidance. But there are also things that we can ALWAYS rely on – our traditions, the laws of Torah that we follow, the way we stick together as a community. No matter what happens, we can always have faith that we as a people will continue. Chukat-Balak, when read together, shows us a complete picture, where loss in the past cannot destroy our hope in the future. And this is an example we can look back on and find hope in whenever we face moments of change or uncertainty in our own lives.

Shabbat shalom!

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Me after basing all of my characters and their relationships after lord huron songs

#lord huron#oc lore#but here we are#screaming crying throwing up#punch me in the face#d'var is so vide noir coded it hurts#and anne#any avatar of vesper is actually

5 notes

·

View notes

Note

Mazel tov!! Did you get a good Torah portion? Mine was the bit about tzedakah and the gleaning of fields, which was real easy to give a speech about. A friend of mine had to do the rules for determining if a red heifer was red enough for Temple sacrifice, so her speech was basically just “look, there’s a lot of stuff in the Torah and not all of it is super meaningful, so we just have to roll with it sometimes.”

Oh nice! My portion was Num 6:18-27, wrapping up the vow of the Nazarite followed up by the priestly blessing. It's the end of a string of vignettes describing how to handle various situations that all feel really disjointed and unrelated at first, so my D'var Torah was all about finding a common thread between them (which basically boiled down to becoming a k'lei kodesh/vessel of holiness by making things better around you)

25 notes

·

View notes

Note

🌻 If you get this, answer with 3 random facts about yourself and send it to the last 7 blogs in your notifications, anonymously or not! Let's get to know the person behind the blog 🌻

i wrote an essay about why i hate my teacher and was going to put it on his desk but then i forgot to print it out

i have a stuffed animal that's a red and green tofu. i got it from my preschool. i'm also pretty sure i stole it

for my d'var torah speech for my bat mitzvah i shat on the torah (specifically cain and abel) enough to get complimented on it for years after. also my rabbi called me a snarkosaurus at my bat mitzvah and im pretty sure that was a direct response to reading my speech

#if youd like to see some absolute gems from my dvar torah tell me and ill deliver#overdue gets some asks#overjew#ask games#anons !!

9 notes

·

View notes

Text

Me, before beginning this story: This story is actually a d'var torah, so I can't really start it until I know what the parsha is when it takes place.

Me, starting the story without having settled on a parsha: the reason I'm having a hard time is that this is going to be actually a d'var torah, and I need to settle on the parsha.

Me, after settling on the parsha and realizing some things I wrote aren't quite right anymore: Good gracious! It's like I'm writing a whole d'var torah here!

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

A Bar Mitzvah: Embracing Responsibility and Tradition

Introduction

The Bar Mitzvah, a central event in Jewish tradition, marks the transition of a Jewish boy from childhood to adulthood. This significant ceremony is more than just a birthday or a party; it's a celebration of maturity, religious responsibility, and cultural identity. In this essay, we will explore the Bar Mitzvah in-depth, delving into its historical origins, its contemporary practices, and its broader cultural and social significance.

Historical Origins

The term "Bar Mitzvah" translates to "son of the commandment" in Aramaic. Its roots can be traced back to ancient Jewish practices, where boys, upon reaching the age of thirteen, were considered morally and ethically responsible for their own actions and for following Jewish law. This concept developed over time, culminating in the modern Bar Mitzvah ceremony.

The Bar Mitzvah ceremony, as we know it today, has evolved significantly from its historical origins. It has become a public affirmation of a boy's commitment to Judaism and his readiness to fulfill religious obligations.

Modern-Day Bar Mitzvah

The Bar Mitzvah ceremony typically takes place when a Jewish boy turns thirteen, though the exact age may vary among different Jewish denominations. The heart of the Bar Mitzvah is the boy's participation in the Torah reading during a synagogue service. He is called to the Torah for an aliyah, an honor that involves reciting a blessing before and after a section of the Torah. This act symbolizes the boy's transition to adulthood and his acceptance of religious responsibilities.

In addition to Torah reading, the Bar Mitzvah boy may lead prayers and deliver a D'var Torah, a commentary on a Torah portion, demonstrating his knowledge of Jewish teachings and his ability to apply them to everyday life.

The ceremony is often followed by a festive celebration, where family and friends come together to honor the Bar Mitzvah boy. Gifts, including religious items and tokens of encouragement, are often given to commemorate the occasion.

Symbolism and Significance

The Bar Mitzvah holds profound symbolism within Jewish culture. It represents a boy's moral and ethical accountability, his commitment to the Jewish faith, and his ability to take on the responsibilities of an adult member of the Jewish community. It reinforces the importance of education and religious study within Judaism, as the boy typically undergoes years of preparation for this event.

Furthermore, the Bar Mitzvah is a powerful expression of Jewish identity. It connects young Jewish boys to their heritage, fostering a sense of belonging to a larger community and reinforcing their Jewish identity. In an ever-changing world, this ceremony provides a strong foundation in Jewish culture and tradition.

The Bar Mitzvah is not only a personal milestone but also a family affair. Parents, siblings, and grandparents take pride in the Bar Mitzvah boy's accomplishment, and the event serves to strengthen family bonds. It emphasizes the importance of generational continuity within Jewish families, passing down traditions and values from one generation to the next.

Conclusion

The Bar Mitzvah is a celebration that embodies tradition, responsibility, and identity. It has evolved over centuries to become a pivotal moment in the lives of Jewish boys, representing their transition to adulthood and their deep connection to their faith and culture. This ceremony continues to play a vital role in shaping the lives of young Jewish men around the world, providing them with a solid foundation for their journey into adulthood and a lifelong connection to their heritage.

A Bat Mitzvah: A Celebration of Transition and Identity

Introduction

The Bat Mitzvah is a significant rite of passage in the Jewish tradition, marking the transition of a Jewish girl from childhood to adulthood. This ceremony, rich in history and symbolism, not only carries religious significance but also serves as a celebration of identity, community, and family. In this essay, we will explore the Bat Mitzvah in depth, delving into its historical origins, its modern-day practices, and its broader cultural and social implications.

Historical Origins

The concept of a Bat Mitzvah, which literally means "daughter of the commandment" in Aramaic, traces its roots back to ancient Jewish customs. Historically, Jewish girls were not included in many religious rituals or counted in a minyan (a quorum of ten Jewish adults required for certain religious services) as boys were. However, over time, Jewish scholars recognized the need for gender equality in religious education and participation.

The first recorded Bat Mitzvah ceremony took place in the early 20th century in America, where Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan's daughter, Judith, was called to the Torah for an aliyah (the honor of reciting a blessing before and after a section of the Torah) during a public service. This event marked the beginning of the modern Bat Mitzvah tradition, which has since evolved and spread worldwide.

Modern-Day Bat Mitzvah

Today, the Bat Mitzvah typically occurs when a Jewish girl reaches the age of twelve, although the exact age may vary among different Jewish denominations. The heart of the Bat Mitzvah ceremony is the girl's opportunity to participate in the Torah reading, symbolizing her readiness to take on the responsibilities and obligations of Jewish adulthood. She may also lead prayers and deliver a D'var Torah, a commentary on a Torah portion, demonstrating her understanding of Jewish teachings.

The ceremony is often celebrated with a festive reception, similar to a wedding or a significant birthday party. Family and friends gather to honor the Bat Mitzvah girl and offer their blessings. Gifts, often including religious items and jewelry, are given to mark this momentous occasion.

Symbolism and Significance

The Bat Mitzvah holds deep symbolic meaning within Jewish culture. It signifies a girl's emergence into adulthood, her moral and ethical responsibilities within the community, and her commitment to the study and practice of Judaism. It also underscores the importance of education in Judaism, as the girl has typically undergone years of religious instruction to prepare for this day.

Furthermore, the Bat Mitzvah serves as a powerful expression of identity. It allows Jewish girls to connect with their heritage, fostering a sense of belonging to a larger community and reinforcing their Jewish identity. In a world of diverse influences, this ceremony provides a firm foundation in Jewish culture and tradition.

Beyond the individual, the Bat Mitzvah also strengthens family ties. Parents and siblings take pride in their daughter's accomplishment, and grandparents often play a significant role in the celebration. It is a moment of unity and shared values, highlighting the importance of generational continuity in Jewish families.

Conclusion

The Bat Mitzvah is a multifaceted celebration, combining religious significance, personal growth, and communal bonds. It has evolved over the years from a groundbreaking event in the early 20th century to an integral part of Jewish life today. Through its customs, rituals, and symbolism, the Bat Mitzvah exemplifies the beauty of tradition, identity, and the enduring strength of community within Judaism. This celebration of transition and identity continues to shape the lives of Jewish girls around the world, providing a solid foundation for their journey into adulthood and a lifelong connection to their heritage.

0 notes

Photo

Inspired by outgoing @ujafedny CFO Irvin Rosenthal, whose D'var Torah was part text, part personal reflection, and all heart. Bless him for 22 years of true professionalism and sacred stewardship. His eyes were full as he spoke, as were mine. May his retirement be blessed. His legacy on behalf of the Jewish People will surely be an enduring blessing. (at UJA-Federation of New York) https://www.instagram.com/p/ClpChVgLyVv/?igshid=NGJjMDIxMWI=

0 notes