#devil didn’t intend for this to happen but the fact that alchemist is there changes everything. she HATES them. they LOVE annoying her.

Text

Fenrir and Greyback: a liiiiiiitle digression about werewolves - part 3: Middle Ages in Central Europe

The Middle Ages in Central Europe are also called Dark Ages in some chronicles or texts from the Renaissance. And that’s not totally without foundation. While many countries in the Middle East and Far East were buzzing with scientific discoveries and progress in science and medicine, the greatest part of what is commonly called the Middle Ages in Central Europe (ca 476-1492 - yet in literature and arts we can date the end around 1300) was dominated by the thought that the Bible was the Law and that anything different was evil. Of course, chemistry developed and some knowledge passed via the Crusades and the spreading of the Muslim Empire, as well as arrived to Europe via travellers, mainly to the Far East. I’m not saying we were ignorant in Europe… but it would take pages to get things totally straight and it’s not the point here. So… that’s a very simplistic summary, but it will have to do for now since I’m not writing philosophy here (not that I wouldn’t like to, mind).

The medieval times were interested in the supernatural. Hugely interested: I mean come on, the basis of the occidental society was belief in God and his miracles. Add to this all the belief in witches (of course, we’re talking here of the times before the witch hunts started, meaning it’s a totally different way of relating to the supernatural). Plus, have a look at all the beasts that are sculpted on church pillars or painted in books: basilisks (see picture), manticores, sirens, etc…. and the medieval scholars were keen on discussing therianthropy, but that was apparently merely to prove that it couldn’t occur because it wasn’t in God’s plans -sighs- or, that it’s a mere vision, like St Augustine thought.

Before the ‘official’ start of Middle Ages, St Augustine mentions the stories about Lycaon and the Lupercalia and the living nine years among wolves (see part 2) in his City of God, book XVIII, chapters 17-18. He is, I think, one of the first writers to state therianthropy is evil and the deed of demons. However, according to St Augustine the transformation doesn’t really affect the mind or body of humans, but he thinks that it’s a sort of vision put into people’s heads by demons. That might have been one of the foundations of the idea that werewolves were actually called by clergy and lords to get the people back to faith if they were ever trying to escape the Claws of the Church.

Wolves

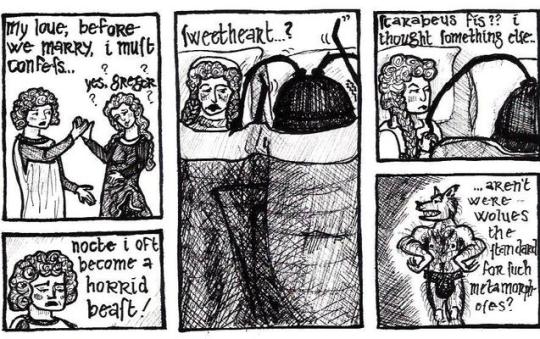

The list of beasts in medieval bestiaries is very very long, yet there are no werewolves. That might be because scholars weren’t interested in the horror part we know since the Renaissance. Besides, the medieval werewolf was a bit different from the one we know today. While retaining the characteristics of a beast, it was merely hiding the human behind. However, wolves existed and so much so that at some points they were a real threat, like during those horrid winters when temperatures went way below freezing point and wolves were entering villages and cities (in the middle of the 15th century in Paris, for instance). They were also pictured as evil animals in the Bible, which meant that they were to be feared and hated: ‘Beware of the false prophets, who come to you in sheep's clothing, but inwardly are ravenous wolves.’ (Matt. 7:15) They were considered stupid and menacing, inedible, useless, and dangerous to people because they could sometimes attack cattle (who would go hunt when food is ready and not struggling too much on the farm?). Wolves aren’t more dangerous than any other wild animal, nor are they useless. About inedible I wouldn’t dare give an opinion. Never tried wolf so far, and don’t intend to.

However, wolves were also honoured in many cultures, like Germanic ones. Many names are derived from Wulf or Wolf or Ulf, for instance, with very positive meanings like ‘friend of the wolf’ (Wolftrud) or Atawulfus (wolf-father). And, ô divine irony, three French patron saints in the catholic church are called ‘Loup (French for wolf), Lubin and Lupicin’ (-can hardly refrain from laughing - can’t. -dies of laughter-). OH MY GOD Lupicin du Jura was one guy who was wearing animal skin instead of clothes! and St Loup is the patron of … sit down and breathe, sip some good Scotch Single Malt … of SHEPHERDS! So yeh… I wonder what the Church makes of that. Her own patron saints being labelled by her as evil. What an oxymoron.

Wolves are also a symbol of power and strength in many northern pagan cultures, like the norse one or the Sami one. We’ll discuss that a bit later…

The thing I think that we must remember from this bit is that wolves are a paradox in our society. Both respected and hated for different reasons. A bit like Lupin, after all.

Werewolves

The werewolves weren’t liked either, because the wolf wasn’t, even if werewolves were hardly ever mentioned. However, the word appears in places I wouldn’t have expected, like King Knut’s law codes (1018-1021, Oxford, Winchester) in which the word refers to an outlaw, that is, someone who is beyond the community’s responsibility because they can’t abide to the law. There’s also a quote from those laws I found in French, that I’ll translate here as well as I can: ‘There’s no more damageable being than the Devil himself … shepherds must be on their guard … so that hungry werewolves don’t strangle and bite members of their spiritual flock’ (Knut the Great, Laws, I § 26, in Lecouteux, 2008 - I tried to find something online but meh).

Middle Ages was also the period of our History when Alchemy was developed. The Grand Oeuvre included of course the making of the Elixir of Life and the Philosopher’s Stone, and alchemists used the werewolf to symbolise the transformation of vile metals into gold… because the werewolf, besides his devilish reputation spread by the Church, had a noble descent in the wolf, who was, in spite of everything, honoured and considered noble. The grey wolf itself was an important symbol in Alchemy: Antimony (chemical symbol Sb; the wolf is also called Lupus metallorum). The whole of this is, of course, no paradox :P.

The Middle Ages also tried to explain the werewolf, and discussed if they could breed and what would become of them. Well, Rowling says the cub of a werewolf wouldn’t be one, and the cub of a werewolf couple would be a wolf. Sort of makes sense. Being a werewolf isn’t genetic, since only the blood is infected, but again, there can be contact between the blood of the mother and that of the cub, and that of both parents with each other’s...

Some sources in the late Middle Ages (Evangile des Quenouilles, in Lecouteux, 2008), says that ‘if a man has as a destiny to become a werewolf, it’s rare that his son wouldn’t be one’. Another tale, this one from Masuria in Poland, tells the story of a boy who had inherited the ability to transform from his father. In this tale there’s nothing linking the transformation with full moon, though. The boy has to flip jump over a stump, though, to transform.

I actually found an even earlier text (10th century) from Ireland that says that some men can change shape at will from generation to generation. The only condition is that when they transform, their body shouldn’t be moved in any way, because otherwise they couldn’t return to their human shape. If the wolf happens to be wounded during its wanderings, then the wound would appear on the man’s body at exactly the same place.

When it comes to explanations, scholars said that full moon was a psychological shock, and that it could be one of the reasons explaining the phenomenon. From the late 12th century, being ‘possessed’ is a very good reason for being a werewolf, and of course this leads to links with devilish practices and witchcraft; the werewolf is a sorcerer who transforms into a beast to do as much harm as possible to his fellow humans. Naturally, this suspicion of witchcraft or any form of magic leads to the idea that balms are used to transform, which is something very frequent. Even men on trial would confess using some kind of magical ointment. The link with witch-hunts is easily made...

Something is a bit odd in all this, though: the fact that some think that actually the body is not transforming, but that it’s the soul that leaves the body and wanders alone in the shape of a wolf. This is something I didn’t expect to find in Central Europe. In my mind it refers more to northern American, European or Siberian native shamanic cultures.

Punished by God

Many medieval texts relate the fact of becoming werewolves as a godly punishment. One of them is about St Patrick. When the priest undertook to convert Ireland to Christianity, there was one tribe that opposed more fiercely than others, and they howled like wolves to Patrick. Patrick then prayed to God that he would punish these people for their blasphemies and their ill-will at receiving the truth of his god, and God decided to punish the tribe by changing them into wolves for a set period of time (either a winter every seventh winter or seven years, depending on the tale). These wolves were told to be more dangerous than natural wolves, because besides their ability to kill, they retained their human brain and could act wild and clever against both cattle and men.

This story goes against the idea that werewolves lose their human part when transforming. There’s a similar story in Norway, also involving St Patrick.

Werewolves ‘by birth’: the Lays and other stories

However, in medieval stories like the Lays by Marie de France and other similar ones, the werewolf is not The Beast, as it is now. The actual bestial aspects are mostly being downplayed. The stories retain more of the human part of the werewolf, as if the beastification couldn’t be complete. Meaning that the werewolf still can reason and judge, and that’s seen mostly when the werewolf attacks, because he never attacks without purpose: usually revenge or the aim to unveil a culprit or identify it. I think the main cause of this is that being a werewolf in those stories is not exactly a curse. You need not have been bitten to be one - or let’s say that nothing is told about that. There’s no dark magic at work. It’s more like a condition you can’t escape and we don’t know where it stems from.

Medieval werewolves were usually male. There is, however, a tale concerning a she-werewolf in Ireland. It is found in Geraldus Cambrensis’s account of the voyages of Prince John to the Green Island. It is a tale that usually goes by the name of the Werewolves of Ossory. Here’s the tale:

In Ireland, there is a strong werewolf-related mythology. According to Geraldus Cambrensis, there are stories about werewolves living in packs in deep forests, sometimes asked for help by local kings in their internal wars. But there’s also this tale about a dying she-werewolf in Ossory.

It all starts with a priest travelling down from Ulster to Meath. He stopped in a forest near Ossory to set up his camp for the night with the clerc boy who travelled with him. The darkness fell and suddenly a voice came from among the trees, calling: ‘Father!’ several times. The priest asked who it was. ‘It is a penitent sinner who seeks only your blessing,’ said the voice. The priest asked the voice to step out into the firelight if they were indeed a repentant sinner. At first the voice refused, pretexting that they were so ugly the priest would run away. A long dialog ensued, where the priest repeatedly asked the voice to come closer and the voice continuously told him he’d be disgusted, whatever the priest would say. Then he added ‘it is not for I that I seek absolution but for she who cannot come.’ Then the priest asked if he was diseased in some way. ‘In a fashion,’ replied the voice. The priest still tried to convince the voice to come forward, and in the end a wolf stepped out into the light and went on speaking with the same voice and polite tone as before.

The priest was shocked and choking with fear, whatever he had told the voice before. The wolf explained: ‘I am under a terrible curse. I must wear this form for seven years before getting back to look like you. Yet in my heart I am still a Christian, and in need of your help and blessing.’ The priest was aghast. ‘Can you vouch for this with all your heart?’ he asked the wolf. ‘Aye, I can. Although we wear this form we are human and in the same need of salvation as any other. I am a member of Clan Allta. It is a tribe of this region. Like you, Father, we believe in God. We were cursed a long time ago for an old sin by the abbot Natalis.’ This was a known name to the priest, who then listened to the wolf more willingly. The wolf went on: ‘My wife and I were chosen to bear the curse over six years ago, but now my wife is dying, hurt by an arrow. She lies in a place not far from here. I beg you, come and minister to her.’

The priest was upset, and the wolf was polite and pleeding. He followed him to his lair. There was a she-wolf, badly wounded. She asked the priest to hear her confession and give her the holy viatic. She had to talk to the priest a long while until he was finally convinced that it wasn’t a trick of the Evil One to lure him out of the paths of God. To be really sure, he said: ‘if only I could see the human in you’. At these words the she-wolf started gnawing at her forepaw and while blood spurted around, the priest saw human fingers appear under the wolf-skin. Then she proceeded to remove more of her wolf-skin. The head appeared and finally the priest believed her and gave her what she had been asking for.

On his way back from Meath, over a year later, the priest stopped in the same woods and went to look for the wolf, but never found a trace of him.

During trials in France, of which there are about 250 accounts (between the years 1423 and 1720), a third of the accused were women, but the charge of their being wereshewolves was generally changed into their being witches, hence the idea that there were no female werewolves I suppose.

So basically, during the Central European Middle Ages, the werewolf was considered the anti-man, the bad and evil side of us, mainly due to the influence of the Church, because according to them, Man is the image of God, and the werewolf, being the deed of a demon, can’t be the image of the revered deity.

I’m going to tell you the well-known story of Bisclavret, because it’s the most popular. If I find more tales worth telling (that is, adding something to what has already been said here) I’ll edit the text.

Bisclavret, Sir Marrok and Tiodel’s Saga

European Middles ages aren’t very prolific in werewolf stories until the 14th century. Before that, we have about four French stories, among which one that has been mentioned and adapted in England and Iceland.

The story is about a werewolf, but apparently not a bad one. Nothing is told about what happens while he transforms. Bisclavret was written by Marie de France in the 12th century, based, according to her, on a story she heard in French Brittany. It’s one of her twelve Lais, a monument in French literature.

Bisclavret means werewolf in Breton language. However, there’s another word for it too, and Marie makes a distinction when she uses them. Apparently ‘Bisclavret’ is used only for that knight in the story, whereas the other word, ‘garwaf’, is used to refer to the more common understanding of the word. To the tale, then.

Bisclavret was a Breton knight, well loved by the king. The tale goes he disappeared every week for three days (notice it’s got nothing to do with full moon). Nobody knew where he went, not even his wife. One day, his wife begs him (probably for the umpteenth time) to tell her what happens. He does oblige, and goes unfortunately as far as to reveal the fact that he must lay his clothes in a particular place to get them back on the third morning, otherwise he can’t go back to human form. You can imagine the lady’s state of mind. She is not only upset, but also angry, and shocked. She tries to find any way to get rid of this man, and comes up with stealing his clothes. She sends a knight whom she knows is in love with her to do the deed. When he comes back with the clothing, she marries him.

A year later, the king goes hunting and his dogs corner Bisclavret. The wolf has a really strange behaviour: it comes to the king, begging him for mercy, kissing his feet. The king decides to be generous and takes Bisclavret to his castle to live with him.

On two different occasions did Bisclavret attack people. When he saw the knight who had married his wife, and when the king took him to visit his former wife, who got her nose torn off. Both the knight and the wife were punished.

The king, who was told by his advisers who the two attacked people were, makes the wife confess the whole business. Thus can Bisclavret get his clothing back, change and return to human form, to the great happiness of the king.

It is said that all the offspring of the wife were born without nose from that day.

The tale of Bisclavret is mentioned twice and very briefly, without mentioning names, in Thomas Malory’s Le Morte d’Arthur, written in the 15th century (published 1485) and has been translated and then adapted in Old Norse under the title Tiodel’s Saga. The werewolf in Le Morte d’Arthur is sometimes called Sir Marrok in other works, and particularly since Allen French made the two sentences in Malory’s tale into a 300-page book in 1902 (for the link to the full text, see sources).

Melion

We don’t know who wrote the lay of Melion. He’s described as a word-player, inferior in quality to Marie de France, who wrote Bisclavret. It was written probably between 1190 and 1204, reset in the Arthurian world. Like in Bisclavret, the werewolf is presented like a sympathetic bloke who has been wronged by his wife and is later ‘saved’ by a king. Here’s a summary of the story:

Melion was a knight at King Arthur’s court. He vows never to marry a woman who has loved before or who has spoken of another man. As a consequence he’s ostracised by all the ladies at Arthur’s court. To comfort him, Arthur gives him land and Melion goes hunting there and soon gets cheerful again.

One day, during his hunt, he meets a lady riding in the forest who claims to be the daughter of the king of Ireland, and of having never spoken of a man before, nor loved one, but Melion. All besotted, Melion marries the lady and they have two children over three happy years.

During one of their hunts, with one of their squires, Melion and his wife see a magnificent stag. The wife gets into a tantrum and swears she will die if she doesn’t eat the meat of that stag. Melion, distressed, promises to get the stag, if he transforms into a wolf, using a ring with two magical stones on it. Melion undresses and asks his wife to keep his clothes and ring safe after he’s transformed so that he can get back to his human form. Then he asks her to touch his head with one of the stones. There goes Melion in a wolf-form behind the stag, a wolf with a human mind.

At once the wife rides to the harbour and to Ireland with the squire. When Melion comes back, he can’t find his wife. He follows her, knowing she would go to her home country. There he starts killing cattle and sheep, so much so that peasants go to the king to complain. The king kills the wolves, but not Melion. The latter is despairing because he can’t get revenge.

One day, though, his hopes rise: there’s a ship approaching the coast: it’s Arthur, who sets camp on the coast. Melion enters Arthur’s tent and lies down at his feet. Melion refuses to be separated from the king. The day after, Arthur and his court, including the wolf, go pay a visit to the king of Ireland. At court, Melion spots the squire whom his wife had run away with, and attacks him. Of course, Melion is threatened, but some say wait, because there must be a reason for such an attack by such a tame wolf. The squire is forced to confess. The ring is brought back to Melion, who can transform to his human self, and returns with Arthur to Britain, without his wife.

The same sort of comments can be made about this text and Bisclavret. After all, they are rather similar, and the scholars say they stem from the same source. Moreover, there is a lot of writings about those lays, the misogyny is debated as well as the knighthood. Sometimes the wife is described as the human counterpart of the werewolf… but that is another story.

And Greyback and Lupin?

In these tales, the werewolf is not bad per se. Only does he seek revenge from those who mistreated him. So nothing in here links the werewolf with either Fenrir or Greyback, apart maybe the idea of revenge, which is nothing particular to werewolves. Yet Greyback started to attack out of spite and for revenge against mankind, and Fenrir was to kill Odin at Ragnarok because of the treatment the gods had been inflicting him. So yeh… some sort of revenge against injustice or an unfavourable fate… Of the two, though, Fenrir is the closest to both Melion and Bisclavret, because he goes for only the one responsible for his fate. Greyback, on the other hand, develops a hatred against mankind so deep he can’t stop himself and actually grows unnaturally into liking his condition. Dumbledore asks him, on the top of the Astronomy Tower, Half-Blood Prince: ‘This is most unusual… You have developed a taste for human flesh that can’t be satisfied once a month?’ and Greyback answers: ‘That’s right. Shocks you, does it? Frightens you?’. Dumbledore is disgusted, as would anybody, I reckon.

Besides, we don’t know what makes the man change into a wolf. The only two things that seem to be important are exiling oneself to the deep of the woods and getting naked. This is in complete contradiction with Greyback, for instance, who positioned himself next to his coming victims to transform and be sure of getting to bite them. Lupin, while at Hogwarts as a student, was led to the Shrieking Shack by Madam Pomfrey, but that was only because the transformation could be scheduled since it was directly linked to the phases of the moon. The nakedness isn’t important in the Harry Potter books either. Lupin transforms without removing his clothes because he hasn’t time to do so in Prisoner of Azkaban. Again, I think this is related to the fact that in the Harry Potter books there’s no ‘magic’ to transform (whereas Melion needs the ring), apart from the power of the moon and the curse in the blood. No somersaults, no running in circles, no peeing, no spells.

Sources for part 3

Page 394

French, Allen, The Tale of Sir Marrok, 1902:

https://ia802305.us.archive.org/14/items/sirmarroktale00frenrich/sirmarroktale00frenrich.pdf

Hopkins, Amanda, Melion and Bisclarel, Two Old French Werwolf lays, Liverpool online series, University of Liverpool, 2005

https://www.liverpool.ac.uk/media/livacuk/modern-languages-and-cultures/liverpoolonline/Werwolf.pdf

Lecouteux Claude, Elle courait le garou - Lycanthropes, hommes-ours, hommes-tigres, une anthologie, José Corti, Paris, 2008

Pottermore, Remus Lupin: https://www.pottermore.com/writing-by-jk-rowling/remus-lupin

Pottermore, Werewolves: https://www.pottermore.com/writing-by-jk-rowling/werewolves

Rowling, Joanne K., Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, Bloomsbury, London, 1999

Rowling, Joanne K., Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince, Bloomsbury, London, 2005

St Augustine, City of God, 426 A.D.:

http://www.unilibrary.com/ebooks/Saint%20Augustine%20-%20City%20of%20God.pdf

The Bible.

The Medieval Werewolf: https://www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/ren/news_and_events/researchblog/werewolf/

The Werewolves of Ossory:

http://www.irelandseye.com/aarticles/culture/talk/banshees/werewolf.shtm

Wikipedia, Bisclavret: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bisclavret

#Louhi#Harry Potter#Werewolves#Middle Ages#Ireland#France#Marie de France#Lais#Mellion#Bisclavret#Ossory#Greyback#Lupin#J.K. Rowling

0 notes