#dutch indonesia

Text

#cindy kimberly#cindykimberly#wolfie cindy#wolfiecindy#wolfiecin#ibiza#spain#mexico#tulum#bali#beach#indonesia#italy#beachgirl#latina#spanish#dutch#amsterdam#netherlands#palm trees#palm tree#palmtree

231 notes

·

View notes

Text

Indonesia lore

#hetalia#hws#hws indonesia#hws Japan#hws Netherlands#nedpan#if you squint#tldr Indonesia being taken over by the Dutch until Japan took over during ww2

91 notes

·

View notes

Text

the dutch and their descendants (esp afrikaners) are the most underrated colonizer ethnicity, like the ratio of the devastation wrought by dutch and afrikaner imperialism compared to the general reputation (particularly within the scope of western awareness lol) that the dutch have for their colonialism is 100:1

#what the dutch empire did in indonesia was fucking insane#like when ppl think of european imperialism theres usually several countries they think of before the dutch empire is even mentioned

118 notes

·

View notes

Text

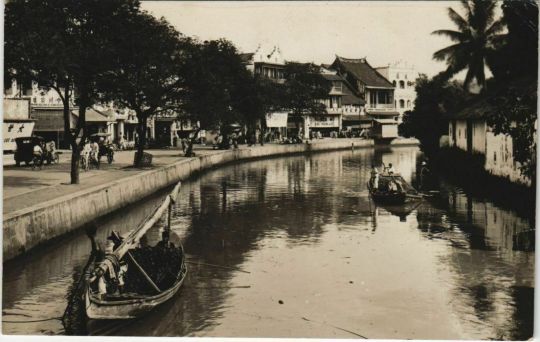

Canal scene in Batavia, modern-day Jakarta, Java, Indonesia

Dutch vintage postcard

#tarjeta#postkaart#indonesia#canal#sepia#dutch#batavia#modern-day#historic#photo#postal#briefkaart#photography#modern#vintage#ephemera#ansichtskarte#old#postcard#day#jakarta#postkarte#scene#carte postale#java

9 notes

·

View notes

Photo

A Market Stall in Batavia, Andries Beeckman (attributed to), Albert Eckhout (rejected attribution), c. 1640 - c. 1666

The Dutch and Malay inscriptions on the piece of paper in the lower right corner identify this as a Dutch painting of subjects studied on the spot. Most of the fruit varieties are found only in Indonesia, the former Dutch East Indies, and were not exported to Europe at the time. The combination of figures from different countries suggests that the setting is most probably the very cosmopolitan Batavia, modern-day Jakarta.8 A Chinese merchant, recognizable as such from his distinctive goatee, moustache and remarkably long fingernails, is counting coins in a fruit stall set off with bamboo partitions. Standing on the left is a woman wearing a typically Javanese sarong and kebaya and holding a small cigar in one hand while placing a durian upright with the other. A second Javanese woman in the middle is lifting a small bundle of leaf wrappers out of a small Japanese lacquered casket, probably betel leaves. A boy behind her is picking a banana from the bunch hanging on the right. A striking salmon-crested cockatoo (Cacatua moluccensis) is perched on the bamboo screen at the back.

Andries Beeckman went to great lengths to depict the huge diversity of tropical fruit as faithfully as possible, but he was clearly not a professional still-life painter. The different varieties are easily distinguished, but their textures are not convincing. Laid out on the table – some with numbers matching the list on the piece of paper (the latter are given between brackets below) – are, on the far left, from top to bottom, rambutans (Nephelium lappaceum, no. 1), langsats (Lansium domesticum, no. 3) and starfruit (Averrhoa carambola, no. 2). Beside them are a partly cut pomelo (Citrus maxima, no. 4) and durians, one of them sliced (Durio, no. 5). The three small pieces of red fruit at bottom left are water or Malay apples (Syzygium aqueum or Syzygium malaccense, no. 6) or Java apples (Syzygium samarangense), and lying to their right are mangoes (Mangifera indica, no. 7) and pineapples (Ananas comosus, no. 8). Below the two pineapples in the centre are jackfruit, one halved (Artocarpus Heteropyllus, no. 9) and several small mangosteens, some opened (Garcinia mangostana, no. 10). On the right are bananas (no. 11), five coconuts and a halved one (Cocos nucifera), and at the very front cashew apples (Anacardium occidentale). The fruit cut in two in the Japanese casket is probably a sort of lime called a Calamondin orange (Citrofortunella microcarpa).

The Rijksmuseum painting is a reduced version of a canvas from an anonymous series of scenes of foreign peoples and produce that decorated the walls of Schloss Pretzsch an der Elbe in Saxony until 1828 (fig. a).9 In the nineteenth century they were removed, first to Berlin and then to Schloss Schwedt an der Oder in Brandenburg.10 They were seen there in the 1930s by Thomsen, who rather hesitantly attributed them to Albert Eckhout and dated them around the middle of the seventeenth century.11 Schwedt was completely destroyed in the closing days of the Second World War, and all that is left of the works of art are pre-war black-and-white photographs making it clear that the attribution to Eckhout is untenable.12

The connection with the canvas from Schloss Pretzsch also led to this Market Stall in Batavia being wrongly attributed to Eckhout or his circle in the past.13 It is woodenly executed, compositionally clumsy, and is not of the kind of Brazilian subject for which Eckhout is known. Minor differences between the two paintings show that they were not copied after each other but seem to share the same or a similar source. The way in which the fruit and cockatoo are depicted displays a clear resemblance to the only known still life by Andries Beeckman (fig. b), and, interestingly, one of the scenes from the series in Pretzsch castle was definitely based on watercolours by him,14 so the present canvas could also be by Beeckman or someone from his circle.

Very little is known about the picture’s provenance, although there are a few early records of an Indonesian fruit market, and since A Market Stall in Batavia is the only surviving work of that nature there is a great temptation to associate it with those early sources. There is, however, nothing that can be said for certain. Around 1660 Jan Vos wrote an ode about paintings in the collection of Joan Huydecooper, among them an ‘East Indies fruit market’: ‘Who has driven me from the north to the east? / I find myself in the market of the East Indies coast. / Here nature displays her fruit as food for life. / The sight makes my mouth desire the beautiful harvest, / Thus is my stomach now sorely overburdened. / Greedy eyes are not soon satiated’.15 It may well be that the poet was referring to the Rijksmuseum canvas.16 There is a second mention of an ‘East Indies fruit market’ a little later in the collection of burgomaster Mattheus van den Broucke of Dordrecht.17 It is far from obvious that it refers to this Market Stall in Batavia. His picture was one of a series of which the others were described as ‘One ditto, with East Indies animals and fruit’, ‘One ditto, being East Indies lodgings, ‘One ditto’, ‘Three ditto, East Indies women’ and ‘A Moorish woman’.18 It is very possible that the Rijksmuseum painting was also part of a larger ensemble of that kind.

Erlend de Groot, 2022

#hanfu#indonesia#art#sarong#Andries Beeckman#kebaya#懒收巾#jingguan#headwear#dutch painting#A Market Stall in Batavia

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

This phenomenon where people who don’t know Indonesian colonial history think Ned is COOL AND CHAD meanwhile people who know Indonesian colonial history:

#hetalia#hws indonesia#aph netherlands#my country oh my country#listen Ned is never cool and chad in my eyes#he’s like#ahahah#pretty pathetic but i say this with part fondness#also he’s not cool because ppl my generation were born with inbuilt knowledge that dutch elders always scolded us

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

We haven't learned. We haven't learned shit at all.

My country's wealth is directly linked to the exploitation and colonization of other peoples. We call the violent acts commited in Indonesia after ww2 "police actions" as if it wasn't horrific crimes against people who were (justifiably) tired of being occupied and abused by foreign invaders and colonizing dickhats.

Sure, we "lost" the Dutch East Indies. We are not actively colonizing anymore. And yet, we still haven't learned a thing. That "VOC mentality" was never gone, it's still there. It's that mentality of thinking business above everything else, money makes right, who cares how horrifically you abuse people, who cares about the massacre of the Banda islands when you now have all the yummy nutmeg to use and sell. It's not something to be admired, it's something we have to address and resolve, but we're not. We're not doing that, but we have to if we ever want justice of any kind.

We're ruled by dickheads who think that saying "from the river to the sea" is a hatecrime that should be condemned. "Yeah sure, you would've probably said the same thing about the utterance of "Republik Indonesia" less than 100 years ago, no?" is what I say to that. We have not successfully freed ourselves of this damn colonizer mindset!

The only reason the Netherlands ever stopped the "police actions" is because we were threatened with sanctions. Post WW2, it was stop the "police actions" (read: many war crimes) or lose the money from the Marshall Plan needed to rebuild your ruined country. The choice was easy enough.

But noooooo, we can't sanction Israel to get them to, ya know, STOP BOMBING HOSPITALS, SCHOOLS AND CIVILIANS IN GENERAL!!! They're our friends! Fuck no. I know why those asshats ain't sanctioning Israel (at least one of the reasons): they'd lose access to fucking Pegasus; spyware surpreme. Wanna spy on some journalists? Perhaps the opposition? Scary activists? Pegasus is THE spyware for you! Infect ppl's phones and suck up All Teh Data wihout them knowing. Suspected detection of the stuff somehow? Self-destruct, boom. Fantastic stuff if you're into violating ppl's privacy. I don't see this talked about a lot, but Israel is Scary in the cyberwarfare department. And they sell this expertise.

I support Palestine. I hope to see it freed someday. Hopefully soon

To Israel(is): decolonize ur shit. I know, it's hard, it's painful, you'll have to question and unlearn a lot of things. Heck, it may give you an existential and/or moral crisis for a bit. I still get one about nutmeg sometimes. But just like desinfecting a wound, it is ultimately beneficial.

PALESTINIAN PEOPLE DESERVE LIFE AS MUCH AS ANY OTHER PEOPLE

#non sims#fire flower speaks#palestine#gaza#free palestine#israel#free gaza#what do you even say when you see such horrific things unfolding almost by the minute#I have been thinking a lot about this ever since our public broadcast shared a video of a literal colonist#she was french and colonizing on the west bank. she was ready to 'shoot the arabs' bc 'they shouldn't be harboring terrorists'#it kinda opened my eyes more to how horrific colonization is#colonization is evil#I cannot do anything about what my country did but I can object to such practices being practiced elsewhere#this is bigger than just palestine#even colonizers have to decolonize themselves#if anyone has any good recommendations on things to watch or read on Dutch colonization of Indonesia please share#or decolonisation in general#I am still learning. Please pardon my ignorance#(and pls send resources so I may work on resolving that)

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

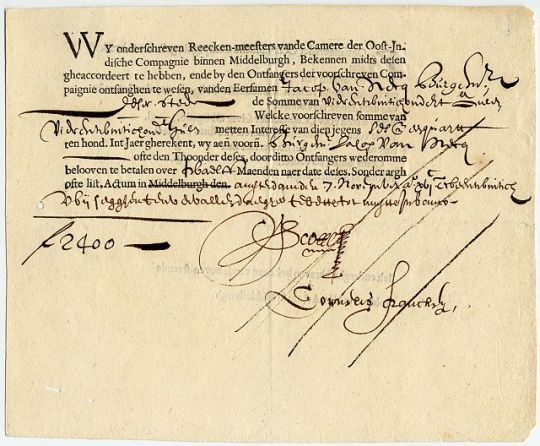

A Dutch East India Company bond, issued to Jacob Van Neck, 1622. Van Neck invested 2,400 guilders and was to be paid back at 6.25% interest over the course of one year. Van Neck was a Dutch ship captain who led a trade expedition to Indonesia in 1599 -- bringing back a million pounds of pepper and cloves -- before retiring to become mayor of Amsterdam. Some great 17th-century signatures at the bottom.

{WHF} {Ko-Fi} {Medium}

83 notes

·

View notes

Text

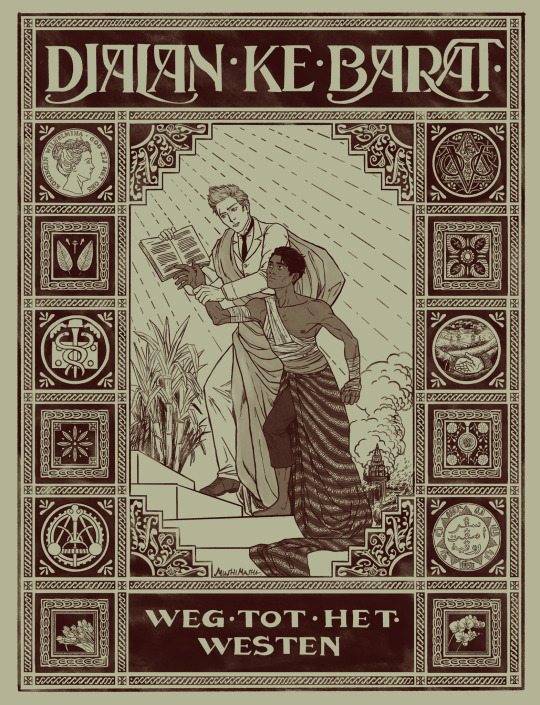

Oops I keep forgetting to post my piece in @hwsrazzledazzle zine… well here it is now!

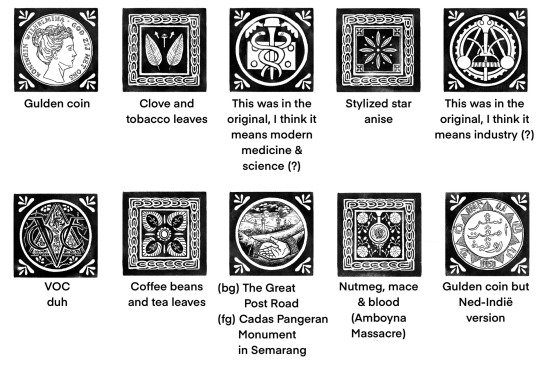

My piece is a redraw of a schoolbook cover specifically made for teaching ‘native’ children of the Dutch East Indies, a product of the efforts under Ethical Policy. The original illustration depicts Ibu Pertiwi shown facing away from the viewer, with the Dutch Maiden kindly guiding her to light. My goal is to subvert that by making Netherlands’ expression less engaged, avoiding eye-contact. He seems to be kind of forcefully pulling Indië (Indonesia) rather than guiding. I’ve also made Indië more confrontational by making him battle-worn and bitter. The decorative illustrations and background are replaced with moments of Dutch conquest and of course, money and spices. The point of this piece here is to show that the start of Ethical Policy was a drastic ‘change of heart’ for the colonial government and quite ironic as during this era it was when Pax Nederlandica was at its peak.

Explanation for the drawings in the background and on the sides, along with the original illustration under the cut!

[The Great Post Road] [Cadas Pangeran] [Amboyna Massacre]

[Puputan Klungkung]

Side-by-side for comparison. This is a schoolbook made specifically made for ‘native’ schools in Ned-Indië, used from the 1920s up until the 50s.

#hetalia#hws indonesia#hws netherlands#hwsrazzledazzle#aph indonesia#aph netherlands#posting both versions because I can’t decide which one I like better#the original idea was to just redraw the little icons on the side but the ref was too low res to make out what it is so i just????#thought it would be cool to get a bit edgy and replace them with some historical points pre-politik etis#and thought that’d be perfect for showing the irony of it all#well stuff that i CAN fit iykwim#and don’t get me wrong i adore the works of og artist c. jetses#but ofc since he worked in a company that publishes schoolbooks for both dutch and indies children#his works reflect the colonial sentiments of that time#what gets me curious is how does he capture not just physical details but social life of indonesians at that time so well#it’s as if he lived there all his life but apparently he never did#i procrastinated too long in posting this#historical hetalia

265 notes

·

View notes

Text

Malaysia that was occupied by Ned for 180 years 🤝 Indonesia that was occupied by Ned for 350 years

#hetalia#hws netherlands#hws malaysia#hws indonesia#technically Indonesia wasnt fully colonised and neither was Malaysia but the Dutch had monopolised the entire trade there#and also acted if they owned the place (with everything included)#also threw portugal out#so you can basically consider it colonised

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Portrait of the painter Raden Syarif Bustaman Saleh, sitting in front of a painting of a seascape with palette, brushes and painter's stick in hand, made c. 1840 and attributed to Friedrich Carl Albert Schreuel. (Rijksmuseum)

A Romantic painter from the Dutch East Indies (as Indonesia was then called), he created this self-portrait in 1841 (Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam):

#Eighteen-Forties Friday#1840s#raden saleh#raden syarif bustaman saleh#indonesia#dutch east indies#romanticism#fashion#historical men's fashion#indonesian artists#art history#early victorian era#victorian

121 notes

·

View notes

Text

TIL:

“Sibori Amsterdam was born around 1654 as the eldest son of Sultan Mandar Syah and his consort Lawa.[1] The Dutch leanings of his father made him name two of his sons after cities in the Netherlands - a junior brother was called Prince Rotterdam.”

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Kartini

Raden Adjeng Kartin (1879-1904) was a prominent Indonesian feminist. Born into an aristocratic Javanese in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia), Kartini valued her own education; it was stopped when she was 12 to begin to prepare for marriage. She began to read and write on the subject of the emancipation of women.

Kartini was married at age 24 to Regent Joyodiningrant of Rembang, where she was his forth wife. She established a women's school in Rembang and died less than a year later, four days after the birth of her only child. After her death, other women's schools (some called 'Kartini's Schools') became more common in Indonesia.

Kartini saw women's emancipation as part of a wider movement for social justice. Though her main focus was women's education, Kartini also valued humanitarians, the Indonesian nationalist movement, self-improvement, and solidarity. She viewed the oppression of Javanese women as by both Dutch colonizers and historically Javanese patriarchy, both of which needed to be overcome.

Kartini is honored in Indonesia on her birthday, April 21st, as Hari Kartini.

#history#solidarity#activisism#feminism#indonesia#indonesian history#kartini#java#dutch colonization

51 notes

·

View notes

Text

Lighthouse of Nusa Kambangan, Java, Indonesia

Dutch vintage postcard

#kambangan#old#postcard#postkaart#indonesia#java#lighthouse of nusa kambangan#lighthouse#vintage#briefkaart#postal#ansichtskarte#ephemera#photography#photo#postkarte#tarjeta#dutch#nusa#historic#sepia#carte postale

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

What are your favorite songs in French, Spanish, Indonesian, Dutch or Chinese? Any recommendations? BTW my taste of music is very eclectic, so any kind of music is welcome as long as it's in the languages above.

#music#music recommendation#foreign languages#language learning#spanish#español#french#français#Nederlands#Dutch#Indonesian#Bahasa Indonesia#Chinese#Duolingo

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Over the week that we spend in Bali, Pak Arwen, the minivan driver, becomes friendly with my father. This happens because they are both Indonesian-Chinese – which is to say that they share a shiver down the spine regarding certain historical dates, political figures and tribalist slurs.

At some point, when it became too difficult to be Chinese in Sumatra, each man's family gambled the present for its future. My father's fled for Singapore and Pak Arwen's for Bali. Decades later, the two men occupy different stations in life: my father plays a tuan to Pak Arwen's supir. But their shared memory of this gamble – and the conditions that forced it – levels the playing field a little.

Both men, being Christian-Chinese, have lived the parable about the pillar of salt. They understand the importance of moving forward, eyes fixed to the line on the horizon.

Is Pak Arwen looking forward or backward when he tells us: This is too much? He says this as we drive past a large banner, stirring in the breeze by the side of the road. The banner is bright red, with a slogan in block capitals: TOLAK REKLAMASI TELUK BENOA. Resist the reclamation of Benoa Bay.

This is one of the first non-English signs that we've seen all day, which makes me think that it's not for tourists. Or perhaps it's for a specific kind of tourist – the kind that's stayed here long enough to perceive that something isn't on offer to them, and want a part in it anyway.

My father asks: What do you mean?

And Pak Arwen responds, one hand circling the steering wheel for eloquence: Nothing is good enough here. Roads, land, water…

The road in front of us is marked by potholes; the banner speaks of land problems. What about water? I sprint through some figures: say there are 5,000 hotels here plus hundreds of unregistered villas, and each one has a pool…

I think about the news stories that I have read, on The Jakarta Post and Al Jazeera. Impossible to describe how much of this island's water goes into making, and maintaining, glamour. Each week, scores of foreign developers reach into Bali's south coast, summoning up yoga studios and restaurants by the dozen. Trump shakes hands with Harry Tanoe and a golfer's empire materialises, sun-bleached and thirsty by the gallon.

But all this diverts water from the poorer North, where most locals live. In this land of glassy infinity pools, more than half the rivers have already run dry. Streams still criss-cross the terraced rice fields of Ubud. But deeper underground, the freshwater banks are pulling back from parched earth. Bali's farmers live the reality that its tourists cannot see – at night, they sleep in their fields with one eye open for irrigation thieves.

Later, I root around online for more stories about Benoa Bay. I learn that Tommy Winata, the Indonesian billionaire, is trying to reclaim land there. He wants to coax hectares of malls, theme parks and an F1 track out of swampland. But this floating world will crush the coral reefs that protect Bali's coastline and keep the sea at bay. Eventually it will flood the island, dragging whole villages into the sea.

In a place like Bali – I tell myself – the supply of pleasure must always meet the demand for it. Even if it costs the future for some people; even if it means death.

After all this is paradise, where nothing ever runs out.

.

Let me tell you another story about Bali that I know. This one is a creation story, concerning the beginnings of paradise.

Imagine that the year is 1906. Bali is an island divided. Dutch forces have occupied the northern territories, leaving three Hindu kingdoms where once there were six. Today, they begin the march south to complete their reign, winding downwards from Tabanan to Badung to the offshore court of Klungkung.

This story is an old one, whose basic tenets are familiar to many people around the world. At heart, it is a story about mismatched means and ends: guns versus kris, ambition versus ancestral claims.

The Dutch troops begin their journey. Quickly, they pass through the city of Kesiman to reach their first stop, Denpasar. At first, the city streets seem too quiet: where is the resistance that they come ready to meet? But as the soldiers advance, they hear something stirring in the distance, from the direction of Denpasar palace: the faint but unmistakable pulse of drums.

And so they go on. As they near the palace, a procession of silent figures files out from its gates. From a distance, they spy the Raja on his palanquin surrounded by courtiers and priests, wives and guards, and children and servants. There are hundreds of people now, robed in white with dusty feet. Flowers laced into their hair.

Both parties, the Dutch and the Balinese, advance. Now there are 200 paces between them; now, 100. The gap between two worlds is narrowing. Then it closes for the century to come, and possibly forever: a puputan commences. The Raja steps down from his palanquin and gives a signal. Instantly someone lunges forward and knifes him in the chest. Motion erupts across the landscape as men force weapons into their children, then stab themselves. Women fling jewels into the air and then topple, wailing, onto their knives.

Dark liquid starts to fill the ground. A metallic scent rises. But Balinese people keep emerging from the palace in a slow, unstoppable stream. When they're within sight of the Dutch troops, they plunge forward onto their daggers, then collapse into the growing snarl of limbs.

Their bodies cover the ground, both protest and decree.

By this point the Dutch soldiers have opened fire, then ceased fire, then opened fire again. They don't know what to do. Several centuries of colonial rule have left them untrained for situations involving consent – and this seems like more than consent, seems close to an invitation. Eventually, they resort to doing what they know best – which is to seize what isn't on offer, looting the corpses for anything that gleams through the sticky mess of fluids.

There will be two more puputans before Bali falls completely, both of them photographed. Eventually, these pictures will cause a kind of moral backlash in Europe, with the thumping of Bibles and pontifical braying. Desperate to hold on to their empire, the Dutch will announce a new resolution: from now on, they will protect Balinese culture and not gun it down. In fact, they resolve to protect Balinese culture so soundly that it never changes from its present state or experiences the advancements of modern life.

Let the world move slowly here, their edicts declare. Progress is not for the pure of heart. Which is what the Balinese people are, presumably – puputans notwithstanding.

For decades to come, Dutch laws will force the Balinese people to wear Baju Endek and not linen pants – to converse in local dialects and not Malay, the regional code of rebellion. All over the island, atap roofs will sprout over modern innovations in galvanised iron. Whole dances will be invented for the Balinese people to perfect, then unleash upon large groups of tourists.

Soon, these tourists will be everywhere, scouring the island with their notepads at the ready – fresh from the war in Europe, and hungry for visions of innocence. Look at this place, they'll say, pointing at random to rice fields and bare-chested women. What authentic culture; what happy natives! So simple and contented with their lot.

They'll forget about the puputans, the cold carpet of bodies.

Bali becomes a paradise on earth.

Island Paradise, Tjoa Shze Hui

19 notes

·

View notes