#e2e

Text

Better failure for social media

Content moderation is fundamentally about making social media work better, but there are two other considerations that determine how social media fails: end-to-end (E2E), and freedom of exit. These are much neglected, and that’s a pity, because how a system fails is every bit as important as how it works.

Of course, commercial social media sites don’t want to be good, they want to be profitable. The unique dynamics of social media allow the companies to uncouple quality from profit, and more’s the pity.

Social media grows thanks to network effects — you join Twitter to hang out with the people who are there, and then other people join to hang out with you. The more users Twitter accumulates, the more users it can accumulate. But social media sites stay big thanks to high switching costs: the more you have to give up to leave a social media site, the harder it is to go:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2021/08/facebooks-secret-war-switching-costs

Nature bequeaths some in-built switching costs on social media, primarily the coordination problem of reaching consensus on where you and the people in your community should go next. The more friends you share a social media platform with, the higher these costs are. If you’ve ever tried to get ten friends to agree on where to go for dinner, you know how this works. Now imagine trying to get all your friends to agree on where to go for dinner, for the rest of their lives!

But these costs aren’t insurmountable. Network effects, after all, are a double-edged sword. Some users are above-average draws for others, and if a critical mass of these important nodes in the network map depart for a new service — like, say, Mastodon — that service becomes the presumptive successor to the existing giants.

When that happens — when Mastodon becomes “the place we’ll all go when Twitter finally becomes unbearable” — the downsides of network effects kick in and the double-edged sword begins to carve away at a service’s user-base. It’s one thing to argue about which restaurant we should go to tonight, it’s another to ask whether we should join our friends at the new restaurant where they’re already eating.

Social media sites who want to keep their users’ business walk a fine line: they can simply treat those users well, showing them the things they ask to see, not spying on them, paying to police their service to reduce harassment, etc. But these are costly choices: if you show users the things they ask to see, you can’t charge businesses to show them things they don’t want to see. If you don’t spy on users, you can’t sell targeting services to people who want to force them to look at things they’re uninterested in. Every moderator you pay to reduce harassment draws a salary at the expense of your shareholders, and every catastrophe that moderator prevents is a catastrophe you can’t turn into monetizable attention as gawking users flock to it.

So social media sites are always trying to optimize their mistreatment of users, mistreating them (and thus profiting from them) right up to the point where they are ready to switch, but without actually pushing them over the edge.

One way to keep dissatisfied users from leaving is by extracting a penalty from them for their disloyalty. You can lock in their data, their social relationships, or, if they’re “creators” (and disproportionately likely to be key network nodes whose defection to a rival triggers mass departures from their fans), you can take their audiences hostage.

The dominant social media firms all practice a low-grade, tacit form of hostage-taking. Facebook downranks content that links to other sites on the internet. Instagram prohibits links in posts, limiting creators to “Links in bio.” Tiktok doesn’t even allow links. All of this serves as a brake on high-follower users who seek to migrate their audiences to better platforms.

But these strategies are unstable. When a platform becomes worse for users (say, because it mandates nonconsensual surveillance and ramps up advertising), they may actively seek out other places on which to follow each other, and the creators they enjoy. When a rival platform emerges as the presumptive successor to an incumbent, users no longer face the friction of knowing which rival they should resettle to.

When platforms’ enshittification strategies overshoot this way, users flee in droves, and then it’s time for the desperate platform managers to abandon the pretense of providing a public square. Yesterday, Elon Musk’s Twitter rolled out a policy prohibiting users from posting links to rival platforms:

https://web.archive.org/web/20221218173806/https://help.twitter.com/en/rules-and-policies/social-platforms-policy

This policy was explicitly aimed at preventing users from telling each other where they could be found after they leave Twitter:

https://web.archive.org/web/20221219015355/https://twitter.com/TwitterSupport/status/1604531261791522817

This, in turn, was a response to many users posting regular messages explaining why they were leaving Twitter and how they could be found on other platforms. In particular, Twitter management was concerned with departures by high-follower users like Taylor Lorenz, who was retroactively punished for violating the policy, though it didn’t exist when she violated it:

https://deadline.com/2022/12/washington-post-journalist-taylor-lorenz-suspended-twitter-1235202034/

As Elon Musk wrote last spring: “The acid test for two competing socioeconomic systems is which side needs to build a wall to keep people from escaping? That’s the bad one!”

https://twitter.com/elonmusk/status/1533616384747442176

This isn’t particularly insightful. It’s obvious that any system that requires high walls and punishments to stay in business isn’t serving its users, whose presence is attributable to coercion, not fulfillment. Of course, the people who operate these systems have all manner of rationalizations for them.

The Berlin Wall, we were told, wasn’t there to keep East Germans in — rather, it was there to keep the teeming hordes clamoring to live in the workers’ paradise out. In the same way, platforms will claim that they’re not blocking outlinks or sideloading because they want to prevent users from defecting to a competitor, but rather, to protect those users from external threats.

This rationalization quickly wears thin, and then new ones step in. For example, you might claim that telling your friends that you’re leaving and asking them to meet you elsewhere is like “giv[ing] a talk for a corporation [and] promot[ing] other corporations”:

https://mobile.twitter.com/mayemusk/status/1604550452447690752

Or you might claim that it’s like “running Wendy’s ads [on] McDonalds property,” rather than turning to your friends and saying, “The food at McDonalds sucks, let’s go eat at Wendy’s instead”:

https://twitter.com/doctorow/status/1604559316237037568

The truth is that any service that won’t let you leave isn’t in the business of serving you, it’s in the business of harming you. The only reason to build a wall around your service — to impose any switching costs on users- is so that you can fuck them over without risking their departure.

The platforms want to be Anatevka, and we the villagers of Fiddler On the Roof, stuck plodding the muddy, Cossack-haunted roads by the threat of losing all our friends if we try to leave:

https://doctorow.medium.com/how-to-leave-dying-social-media-platforms-9fc550fe5abf

That’s where freedom of exit comes in. The public should have the right to leave, and companies should not be permitted to make that departure burdensome. Any burdens we permit companies to impose is an invitation to abuse of their users.

This is why governments are handing down new interoperability mandates: the EU’s Digital Markets Act forces the largest companies to offer APIs so that smaller rivals can plug into them and let users walkaway from Big Tech into new kinds of platforms — small businesses, co-ops, nonprofits, hobby sites — that treat them better. These small players are overwhelmingly part of the fediverse: the federated social media sites that allow users to connect to one another irrespective of which server or service they use.

The creators of these platforms have pledged themselves to freedom of exit. Mastodon ships with a “Move Followers” and “Move Following” feature that lets you quit one server and set up shop on another, without losing any of the accounts you follow or the accounts that follow you:

https://codingitwrong.com/2022/10/10/migrating-a-mastodon-account.html

This feature is as yet obscure, because the exodus to Mastodon is still young. Users who flocked to servers without knowing much about their managers have, by and large, not yet run into problems with the site operators. The early trickle of horror stories about petty authoritarianism from Mastodon sysops conspicuously fail to mention that if the management of a particular instance turns tyrant, you can click two links, export your whole social graph, sign up for a rival, click two more links and be back at it.

This feature will become more prominent, because there is nothing about running a Mastodon server that means that you are good at running a Mastodon server. Elon Musk isn’t an evil genius — he’s an ordinary mediocrity who lucked into a lot of power and very little accountability. Some Mastodon operators will have Musk-like tendencies that they will unleash on their users, and the difference will be that those users can click two links and move elsewhere. Bye-eee!

Freedom of exit isn’t just a matter of the human right of movement, it’s also a labor issue. Online creators constitute a serious draw for social media services. All things being equal, these services would rather coerce creators’ participation — by holding their audiences hostage — than persuade creators to remain by offering them an honest chance to ply their trade.

Platforms have a variety of strategies for chaining creators to their services: in addition to making it harder for creators to coordinate with their audiences in a mass departure, platforms can use DRM, as Audible does, to prevent creators’ customers from moving the media they purchase to a rival’s app or player.

Then there’s “freedom of reach”: platforms routinely and deceptively conflate recommending a creator’s work with showing that creator’s work to the people who explicitly asked to see it.

https://pluralistic.net/2022/12/10/e2e/#the-censors-pen

When you follow or subscribe to a feed, that is not a “signal” to be mixed into the recommendation system. It’s an order: “Show me this.” Not “Show me things like this.”

Show.

Me.

This.

But there’s no money in showing people the things they tell you they want to see. If Amazon showed shoppers the products they searched for, they couldn’t earn $31b/year on an “ad business” that fills the first six screens of results with rival products who’ve paid to be displayed over the product you’re seeking:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/11/28/enshittification/#relentless-payola

If Spotify played you the albums you searched for, it couldn’t redirect you to playlists artists have to shell out payola to be included on:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/09/12/streaming-doesnt-pay/#stunt-publishing

And if you only see what you ask for, then product managers whose KPI is whether they entice you to “discover” something else won’t get a bonus every time you fatfinger a part of your screen that navigates you away from the thing you specifically requested:

https://doctorow.medium.com/the-fatfinger-economy-7c7b3b54925c

Musk, meanwhile, has announced that you won’t see messages from the people you follow unless they pay for Twitter Blue:

https://www.wired.com/story/what-is-twitter-blue/

And also that you will be nonconsensually opted into seeing more “recommended” content from people you don’t follow (but who can be extorted out of payola for the privilege):

https://www.socialmediatoday.com/news/Twitter-Expands-Content-Recommendations/637697/

Musk sees Twitter as a publisher, not a social media site:

https://twitter.com/elonmusk/status/1604588904828600320

Which is why he’s so indifferent to the collateral damage from this payola/hostage scam. Yes, Twitter is a place where famous and semi-famous people talk to their audiences, but it is primarily a place where those audiences talk to each other — that is, a public square.

This is the Facebook death-spiral: charging to people to follow to reach you, and burying the things they say in a torrent of payola-funded spam. It’s the vision of someone who thinks of other people as things to use — to pump up your share price or market your goods to — not worthy of consideration.

As Terry Pratchett’s Granny Weatherwax put it: “Sin is when you treat people like things. Including yourself. That’s what sin is.”

Mastodon isn’t perfect, but its flaws are neither fatal nor permanent. The idea that centralized media is “easier” surely reflects the hundreds of billions of dollars that have been pumped into refining social media Roach Motels (“users check in, but they don’t check out”).

Until a comparable sum has been spent refining decentralized, federated services, any claims about the impossibility of making the fediverse work for mass audiences should be treated as unfalsifiable, motivated reasoning.

Meanwhile, Mastodon has gotten two things right that no other social media giant has even seriously attempted:

I. If you follow someone on Mastodon, you’ll see everything they post; and

II. If you leave a Mastodon server, you can take both your followers and the people you follow with you.

The most common criticism of Mastodon is that you must rely on individual moderators who may be underresourced, incompetent on malicious. This is indeed a serious problem, but it isn’t the same serious problem that Twitter has. When Twitter is incompetent, malicious, or underresourced, your departure comes at a dear price.

On Mastodon, your choice is: tolerate bad moderation, or click two links and move somewhere else.

On Twitter, your choice is: tolerate moderation, or lose contact with all the people you care about and all the people who care about you.

The interoperability mandates in the Digital Markets Act (and in the US ACCESS Act, which seems unlikely to get a vote in this session of Congress) only force the largest platforms to open up, but Mastodon shows us the utility of interop for smaller services, too.

There are lots of domains in which “dominance” shouldn’t be the sole criteria for whether you are expected to treat your customers fairly.

A doctor with a small practice who leaks all ten patients’ data harms those patients as surely as a hospital system with a million patients would have. A small-time wedding photographer who refuses to turn over your pictures unless you pay a surprise bill is every bit as harmful to you as a giant chain that has the same practice.

As we move into the realm of smalltime, community-oriented social media servers, we should be looking to avoid the pitfalls of the social media bubble that’s bursting around us. No matter what the size of the service, let’s ensure that it lets us leave, and respects the end-to-end principle, that any two people who want to talk to each other should be allowed to do so, without interference from the people who operate their communications infrastructure.

Image:

Cryteria (modified)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:HAL9000.svg

CC BY 3.0

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en

Heisenberg Media (modified)

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Elon_Musk_-_The_Summit_2013.jpg

CC BY 2.0

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/deed.en

[Image ID: Moses confronting the Pharaoh, demanding that he release the Hebrews. Pharaoh’s face has been replaced with Elon Musk’s. Moses holds a Twitter logo in his outstretched hand. The faces embossed in the columns of Pharaoh’s audience hall have been replaced with the menacing red eye of HAL9000 from 2001: A Space Odyssey. The wall over Pharaoh’s head has been replaced with a Matrix ‘code waterfall’ effect. Moses’s head has been replaced with that of the Mastodon mascot.]

#pluralistic#e2e#end-to-end#freedom of reach#mastodon#interoperability#social media#twitter#economy#creator economy#artists rights#content moderation#como#right of exodus#let my tweeters go#exodus#right of exit#technological self-determination

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

adrenaline rush ❄️💙

more fanart i did for @lsoer ‘s BTVS au fic - chapter 23 held me hostage and made me go insane

#gustholomule#the owl house#gus porter#matt tholomule#toh fanart#toh au#e2e#augustus porter#toh mattholomule#TWO MEN KISSINK……..#i’m so fucking crazy about them losing my mind#can’t wait for eli to fucking destroy me with more angst but the fluff has been nice#me posting all of my e2e fanart in one day cause i couldn’t wait#steph draws#x

105 notes

·

View notes

Link

Chapters: 1/1

Fandom: The Owl House (Cartoon)

Rating: Teen And Up Audiences

Warnings: No Archive Warnings Apply

Relationships: Mattholomule/Gus Porter

Characters: Gus Porter, Mattholomule (The Owl House)

Additional Tags: Gustholomule Week 2024, Gustholomule, e2e, bvts au, Vampire Slaying, Fluff

Series: Part 7 of Gustholomule Week 2023, Part 2 of e2e-verse

Summary:

Gustholomule Week 2024 day 2: Vampires

e2e-inspired drabble about Gus and Matt's (almost?) perfect date night.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

E2E does a lot of things that I'm not a massive fan of, but making one of the crafting recipes literally just 10,000 minecraft pistons is extremely fucking funny

10 notes

·

View notes

Video

Life in kalash

مسکرائیے!

دنیا کے سارے غم آپ کی ملکیت تھوڑی ہیں..😂

Contact us Right Now for checking such amazing point and explore the globe with 𝐄𝟐𝐄 𝐓𝐫𝐚𝐯𝐞𝐥 𝐀𝐧𝐝 𝐓𝐨𝐮𝐫.

#e2e#e2e travel and tour#e2etravel#e2e travel & tour#explore globe with e2e travel#e2e travel#e2e travel tour#kalash#kalash valley#kalash life#life in kalash

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

looking for friends to play tech modded mc i want to share my interests with other people!!

#mineblr#minecraft#minecraft mods#gtnh#e2e#allthemods#gregtech#nomifactory#anything techy goes honestly#even some skyblock i just want to share my passion for block machines!!!#create even if you're into that#magic mods are also kinda enjoyable doesn't have to be 100% tech

0 notes

Text

Online Safety Bill verabschiedet

GB einen Schritt näher am Abgrund

Konnten wir vor wenigen Tagen noch erleichtert sein, dass die Abstimmung zur EU Chatkontrolle von der Tagesordnung genommen wurde, so ist Großbritannien schon "einen Schritt weiter". Das britische Parlament hat das Gesetz zur Online-Sicherheit (Online Safety Bill - OSB) verabschiedet, das das Vereinigte Königreich zum "sichersten Ort" der Welt machen soll.

Das Gegenteil ist nun der Fall. In Wirklichkeit wird das OSB zu einem viel stärker zensierten, abgeschotteten Internet für britische Nutzer führen. Der Gesetzentwurf könnte die Regierung ermächtigen, nicht nur die Privatsphäre und die Sicherheit der Einwohner Großbritanniens, sondern der Internetnutzer weltweit zu untergraben.

Eine Hintertür, die die Verschlüsselung untergräbt

Die Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF) beschreibt dies so: Das Gesetz erlaubt es Ofcom, der britischen Telekom-Regulierungsbehörde, eine Mitteilung zu verschicken, die Tech-Unternehmen dazu verpflichtet, ihre Nutzer - und zwar alle - auf Inhalte mit Kindesmissbrauch zu scannen. Dies würde sogar Nachrichten und Dateien betreffen, die zum Schutz der Privatsphäre der Nutzer Ende-zu-Ende verschlüsselt sind. Das OSB erlaubt es der Regierung, Unternehmen zu zwingen, Technologien zu entwickeln, die unabhängig von der Verschlüsselung scannen können - mit anderen Worten, eine Hintertür zu bauen.

Damit wird die Privatsphäre und die Sicherheit aller Menschen weltweit untergraben. Paradoxerweise hat der britische Gesetzgeber dieses neue Gesetz im Namen der Online-Sicherheit geschaffen.

Das OSB wird - wie auch bei der EU Chatkontrolle - zu schädlichen Altersverifikationssystemen führen. Dies verstößt gegen grundlegende Prinzipien des anonymen und einfachen Zugangs, die seit den Anfängen des Internets gelten. Man sollte seinen Ausweis nicht vorzeigen müssen, um online zu gehen. Alterskontrollsysteme, die Kinder ausschließen sollen, führen unweigerlich dazu, dass Erwachsene ihr Recht auf private und anonyme Meinungsäußerung verlieren, welches manchmal notwendig sein kann.

Mehr dazu bei https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2023/09/today-uk-parliament-undermined-privacy-security-and-freedom-all-internet-users

und alle Artikel zur EU-Chatkontrolle https://www.aktion-freiheitstattangst.org/cgi-bin/searchart.pl?suche=chatkontrolle&sel=meta

Kategorie[21]: Unsere Themen in der Presse Short-Link dieser Seite: a-fsa.de/d/3wo

Link zu dieser Seite: https://www.aktion-freiheitstattangst.org/de/articles/8533-20230924-online-safety-bill-verabschiedet.htm

#GB#Großbritannien#EU#Chatkontrolle#Buschmann#E2E#scannen#mitlesen#Inhaltskontrolle#Ausweiskontrolle#Lauschangriff#Überwachung#Vorratsdatenspeicherung#Videoüberwachung#Rasterfahndung#Freizügigkeit#Unschuldsvermutung#Verhaltensänderung#Smartphone#Handy#Grundrechtecharta#Erstellt: 2023-09-24 08:30:58#Kommentar abgeben#Kommentar#wie Session#Bitmessage#o.ä. anzugeben.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Điều kiện du học Canada cập nhật mới 2023

Điều kiện du học Canada năm 2023 bạn cần điểm trung bình bao nhiêu? Điểm IELTS/TOEFL thế nào? Du học canada cần gì cần tài chính ra sao? Đó là những câu hỏi gần đây chúng tôi nhận được rất nhiều từ các bạn học sinh, sinh viên và các bậc phụ huynh.

0 notes

Text

Google #Autenticator carece de cifrado de extremo a extremo en su backup en la nube

Esta semana les conté el podcast que la App Google Autenticator, anunciaba el sistema de backup en la nube. Con lo cual podes instalarlo en varios equipos y ademas moverlo de uno hacia otro sin tener que escanear los códigos de doble factor de autenticación de forma manual.Hoy les cuento que le esta faltando una función muy importante, y la misma es que no tiene hasta el momento cifrado de…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

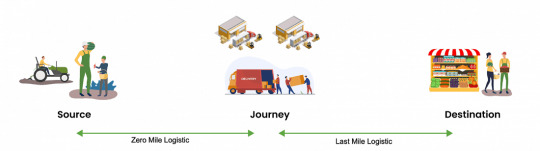

Supply Chain Management — To Build or To Buy?

An end-to-end (E2E) Supply Chain has many nodes based on the scale of operations involved. A journey that starts with a Source Market and traverses through multiple miles until it reaches the Destination Market.

The journey has multiple challenges that change based on multiple factors like the kind of SKUs involved, sourcing personas, target audience personas, the scale of the business, coverage of the business, geographic location of the business and many more. The dynamic nature of the challenges makes it very difficult to standardize the solution.

Problems in Building an Agri Supply Chain

The problems faced by Agritech companies building a supply chain are almost the same regardless of the country:

Demand v/s Supply dilemma

Pricing

Margins

Fraud

Inventory Management

The Ninjacart Supply Chain Management Solution

So, should you build a Supply Chain Management Solution-from scratch-based on your needs and challenges to provide you with a pinpointed solution?

Arranging for funds to build your own system is the least of your worries. The main challenge is the time-taking process and the long learning curve. It will take years to build an entire E2E Supply Chain Management System based on your needs, and then additional years to stabilize the same.

You should instead partner with similar players in the field who have built and fine-tuned the solution for years.

Ninjacart, while starting its journey in an untapped area of F&V, didn’t have a choice to buy or even partner with one who has the experience, So we built.

The best way is to try and use the Supply Chain Management Platform build over the years and stabilized based on practical on-ground experience. Though at Ninjacart we have taken the second option to build the platform by ourselves, and it took us all these years to reach a level where our SCM platform delivers us what is exactly needed in our ecosystem.

We at Ninjacart didn’t have a choice to pick a solution which has been developed and stabilize over the years, but you have the opportunity.

Ninjacart is calling out startups to join hands with our Tech.

0 notes

Text

Nothing would thrill Hannibal more than seeing this roof collapse.

#minegifs#hannibal gifs#hannibal#nbc hannibal#hannibal lecter#will graham#mads mikkelsen#hugh dancy#hannibalgifs#hannigram#hannibal s3 e2#primavera

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Saving the news from Big Tech with end-to-end social media

Big Tech steals from the news, but it doesn’t steal *content* — it steals *money*. In “Saving the News From Big Tech,” a series for EFF, I’ve documented how tech monopolies in ad-tech and app stores result in vast cash transfers from the news to tech, starving newsrooms and gutting reporting:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2023/04/saving-news-big-tech

Now we’ve published the final part, describing how social media platforms hold audiences hostage, charging media companies to reach the subscribers who asked to see what they have to say. And, as with the previous installments, we set out a proposal for forcing tech companies to end this practice, putting more money in the pockets of news producers:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2023/06/save-news-we-need-end-end-web

The issue here is final stage of the enshittification cycle: first, platforms offer good deals and even subsidies to lure in end users. Then, once the users are locked in, platforms offer similarly good deals to business users (in this case, publishers, but see also Uber drivers, Amazon sellers, YouTube performers, etc) to lure them in. Once *they’re* locked in, the platform flips the script: it withdraws subsidies from both end users and business customers (e.g. news readers and news publishers) and forces both groups to pay to continue to transact with each other.

In the case of the news and Big Tech, that process goes like this. First a platform like Facebook offers users a surveillance-free alternative to MySpace, where the deal is simple: tell us who matters to you on this site, and we’ll show you what they post:

https://lawcat.berkeley.edu/record/1128876?ln=en

Users pile in and lock themselves in, through the “collective action problem” — the difficulty of convincing all your friends to leave, and to agree on where to go:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2021/08/facebooks-secret-war-switching-costs

Then Facebook turns on the surveillance they promised they’d never engage in, and also begins to promise media companies that it will nonsensually cram their posts down readers’ eyeballs, luring in both advertisers and publishers. Users don’t like their diluted feeds, or the surveillance, or the ads, but they like each other, and the collective action problem keeps them from leaving.

As publishers and advertisers grow increasingly dependent on Facebook, Facebook makes the deal worse for both. Ad prices go up, as does ad-fraud, meaning advertisers pay ever more for ads that are ever less likely to be shown to a user.

Publishers’ “reach” is curtailed unless they put ever-larger excerpts onto Facebook, until they eventually must publish whole articles verbatim on the platform, making it a substitute for their web presence, rather than a funnel to drive traffic to their own sites. Facebook caps this off by downranking any post that includes a link to the public web, forcing publishers into the conspiracy to make “Facebook” synonymous with “the internet.”

Then, in end-stage enshittification, publishers’ reach is curtailed altogether. They are told — either explicitly or implicitly — that they have to pay to “boost” their material to reach the subscribers who asked to see it.

With social media ransom, tech finds a way to steal money from publishers no matter how they make that money. Tech monopolists command 51% of ever ad dollar. Tech monopolists rake off 30% of every in-app subscription dollar. And social media companies demand danegeld (“verification,” “boosting,” etc) from publishers who want to reach the audiences that asked to see their materials.

This isn’t just bad for publishers, it’s also bad for audiences. You joined the platform to see the feeds you subscribed to, but the platform gradually replaces more and more of your feed with ads and content from randos who pay to “boost” into your field of vision, at the expense of the friends, communities and publishers you asked to see:

https://pluralistic.net/2022/12/10/e2e/#the-censors-pen

What can we do about this? The answer lies in the founding ethic of the internet itself: the end-to-end principle.

Before the internet, telecommunications were controlled by centralized phone companies. If you wanted to reach someone else, you needed to connect to a centralized switching center, which decided whether to connect you, and if so, what to charge you.

The internet, by contrast, operates on the “end-to-end principle”: the job of the network is to transmit data from willing senders to willing receivers, as efficiently and reliably as possible. One expression of end-to-end is Network Neutrality, the idea that carriers shouldn’t be allowed to slow down the data you request unless the service you’re trying to use pays for “premium carriage.”

Social media has run the internet transitions in reverse. They started off as end-to-end, neutral platforms. You created an account, told them which data you wanted, and they put it in a feed for you. Then, as they enshittified, they turned into miniature Ma Bells. You don’t get the data you requested, you get the data that someone is willing to pay to show you.

This means that publishers — including news publisher — have to pay ever-larger shares of their revenues to reach the people who asked to hear from them, and those people see an ever smaller proportion of the things they asked to see in their feeds.

The solution to this is to enshrine “end-to-end” delivery for social media: to make social media platforms’ first duty to deliver data from willing senders to willing recipients, as efficiently and reliably as possible:

https://locusmag.com/2023/03/commentary-cory-doctorow-end-to-end/

As a policy, end-to-end has a lot going for it. First, it is easy to administer. If you want to find out if a company is reliably delivering posts from willing senders to willing receivers, you can easily verify it by creating accounts and performing experiments. Compare this to more complicated policies, like “platforms must not permit harassment on their services.” To administer that policy, you need to agree on a definition of harassment, agree on whether a specific user’s conduct rises to the level of harassment, then investigate whether the platform took reasonable steps to prevent it.

These fact-intensive questions are the enemy of effective enforcement. Bad actors can (and do) exploit definitional ambiguity to engage in conduct that *almost* rises to the level of harassment, and which is *experienced* as harassment, but which doesn’t qualify as harassment:

https://doctorow.medium.com/como-is-infosec-307f87004563

Then there’s the problem of figuring out whether platforms’ failures to block harassment are reasonable or negligent, a question that can literally take *years* to resolve, and then only by deposing the engineers who build and maintain the systems involved.

By contrast, detecting end-to-end violations is simple and clean, and has an easy remedy in the event that violations are detected: if a company doesn’t deliver the messages it is supposed to deliver, a regulator or court can order it to do so.

Another important advantage of end-to-end: it is a *cheap* policy to comply with. Complicated platform regulations can have the perverse effect of being so expensive to comply with that only the largest — and worst, and most harmful — platforms can afford to follow the rule. That means that smaller platforms — including nonprofits, co-ops, and small businesses — are snuffed out by compliance costs, trapping users and business customers in giant, abusive walled gardens, forever:

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2023/04/platforms-decay-lets-put-users-first

Imposing an end-to-end requirement on platforms would kill the practice of holding news publishers’ audiences for ransom. What’s more, it’s a policy that would benefit both large and small publishers — unlike, say, a profit-sharing arrangement between Big Tech and the news, which delivers disproportionate benefits to the largest publishers, whose owners are typically either billionaire dilettantes or private equity looters. And, unlike profit-sharing arrangements, end-to-end continues to provide value for publishers even if the tech companies crash and burn, or get broken up by regulators. We want our news to be adversaries and watchdogs for Big Tech, not its partners, with a shared stake in Big Tech’s growth and profits.

Now that the EFF “Saving the News” series is done, we’re rounding up the whole thing into a PDF “white paper,” suitable for emailing to your friends, elected representatives, and fellow news junkies. That’ll be up in a day or two, and I’ll post here when it is. In the meantime, here are the five parts:

Saving the News From Big Tech https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2023/04/saving-news-big-tech

To Save the News, We Must Shatter Ad-Tech https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2023/05/save-news-we-must-shatter-ad-tech

To Save the News, We Must Ban Surveillance Advertising https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2023/05/save-news-we-must-ban-surveillance-advertising

To Save the News, We Must Open Up App Store https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2023/06/save-news-we-must-open-app-stores

To Save the News, We Need an End-to-End Web https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2023/06/save-news-we-need-end-end-web

If you’d like an essay-formatted version of this post to read or share, here’s a link to it on pluralistic.net, my surveillance-free, ad-free, tracker-free blog:

https://pluralistic.net/2023/06/13/certified-organic-reach/#e2e

[Image ID: EFF's banner for the save news series; the word 'NEWS' appears in pixelated, gothic script in the style of a newspaper masthead. Beneath it in four entwined circles are logos for breaking up ad-tech, ending surveillance ads, opening app stores, and end-to-end delivery. All the icons except for 'end-to-end delivery' are greyed out.]

Image:

EFF

https://www.eff.org/deeplinks/2023/06/save-news-we-need-end-end-web

CC BY 3.0

https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/deed.en

#pluralistic#boosting#end to end#social media#saving the news from big tech#news#copyfight#eff#e2e#net neutrality#administratability#compliance costs#monopoly#trustbusting#media#antitrust

195 notes

·

View notes

Text

finally getting around to posting my art for eyeballs to entrails, the buffy the vampire slayer gustholomule AU by @lsoer 🫶 highly recommend this fic!!

obsessed with this specific scene from chapter 10 - snippet under the cut

#the owl house#gustholomule#gus porter#matt tholomule#toh fanart#toh au#e2e#augustus porter#toh mattholomule#gus the vampire slayer my favorite thing ever…#had plans to clean these up but decided to just color my sketches instead. got lazy LMAO#eli’s matt curly hair agenda must be spread#matt shoving a waffle in his mouth without using utensils is something that can be so personal#steph draws#x

125 notes

·

View notes

Text

StoP the scene where he is waiting by himself during capture the flag and just enjoying nature and bonding with the wildlife SCREAMS Percy. What if I was sobbing

#my sweet sweet child#pjo#percy jackson#percy jackson and the olympians#pjo disney#pjo disney+#pjo s1 e2#clarisse la rue#annabeth chase#grover underwood#sally jackson#pjo spoilers#spoilers#percy jackson spoilers

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

They mirrored the Job story

I don’t know if this has been said yet, but during the Job episode I was extremely preoccupied with the “sounds lonely” arc, preoccupied with Aziraphale changing, but I noticed something else.

There is something about that scene in the villa, where Aziraphale asks Crowley not to destroy Job’s children. Now, we know Crowley never had any plans to do this, so why would he lie to Aziraphale instead of just admitting it? Does he actually want to seem that demonic to him, does he want him to think he’s evil?

I don’t think so. At least, that isn’t the way I interpreted it.

I think Crowley was testing Aziraphale’s faith in him. He looks him in the eyes, he tells him he’s going to go through with it, and he watches his reaction. Aziraphale is on the verge of tears when he walks away, and when Crowley goes the opposite direction, you can see he looks a little disappointed.

Then Aziraphale finds out he didn’t kill the goats. And like that, his faith in him is restored.

So what does Crowley do? Just like God with Job, he escalates. He raises the stakes.

Next time, it’s the fire. The “are you sure, angel?” gets me every single time. He is looking Aziraphale in the eyes and asking for his faith, and Aziraphale looks back at him and this time, he gives it resolutely, firmly. Quite sure. And after that, Crowley doesn’t test him again.

It’s just so interesting to think about the state of their relationship at this point—the fact that Crowley is, relative to the rest of their existence, newly fallen. They’re treading this new ground, and Crowley doesn’t know where he stands in Aziraphale’s eyes. So in his own weird, definitely-not-trauma-fueled way, he decided to find out.

#good omens#ineffable husbands#crowley#aziraphale#aziracrow#good omens season 2#go2 spoilers#analysis#good omens 2#john finnemore#neil gaiman#good omens meta#s2 e2

943 notes

·

View notes

Text

aabria, having just described that the parasitically-piloted actively-collapsing dead bear body the party is CURRENTLY STANDING INSIDE OF as a "deflated basketball", dismayed her party does not seem thrilled by this analogy: Ball is life!! >:(

#and shes right. ball is LIFE. even when the ball is dead and also collapsing and also. again. SO dead.#burrows end#burrows end e2#burrows end spoilers#d20 cast#aabria iyengar#shitpost#im slowly but surely making my way thru the second half. im trying so hard.#not cr#dropout#dimension 20

2K notes

·

View notes