#ecosystem restoration

Text

In the Willamette Valley of Oregon, the long study of a butterfly once thought extinct has led to a chain reaction of conservation in a long-cultivated region.

The conservation work, along with helping other species, has been so successful that the Fender’s blue butterfly is slated to be downlisted from Endangered to Threatened on the Endangered Species List—only the second time an insect has made such a recovery.

[Note: "the second time" is as of the article publication in November 2022.]

To live out its nectar-drinking existence in the upland prairie ecosystem in northwest Oregon, Fender’s blue relies on the help of other species, including humans, but also ants, and a particular species of lupine.

After Fender’s blue was rediscovered in the 1980s, 50 years after being declared extinct, scientists realized that the net had to be cast wide to ensure its continued survival; work which is now restoring these upland ecosystems to their pre-colonial state, welcoming indigenous knowledge back onto the land, and spreading the Kincaid lupine around the Willamette Valley.

First collected in 1929 [more like "first formally documented by Western scientists"], Fender’s blue disappeared for decades. By the time it was rediscovered only 3,400 or so were estimated to exist, while much of the Willamette Valley that was its home had been turned over to farming on the lowland prairie, and grazing on the slopes and buttes.

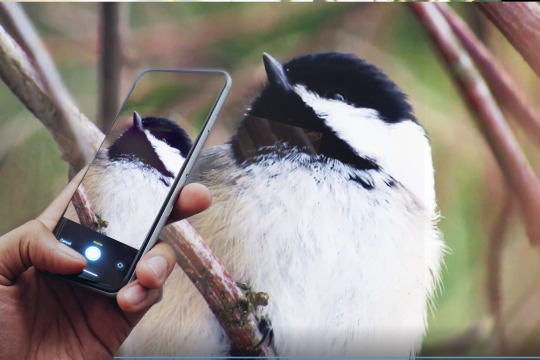

Pictured: Female and male Fender’s blue butterflies.

Now its numbers have quadrupled, largely due to a recovery plan enacted by the Fish and Wildlife Service that targeted the revival at scale of Kincaid’s lupine, a perennial flower of equal rarity. Grown en-masse by inmates of correctional facility programs that teach green-thumb skills for when they rejoin society, these finicky flowers have also exploded in numbers.

[Note: Okay, I looked it up, and this is NOT a new kind of shitty greenwashing prison labor. This is in partnership with the Sustainability in Prisons Project, which honestly sounds like pretty good/genuine organization/program to me. These programs specifically offer incarcerated people college credits and professional training/certifications, and many of the courses are written and/or taught by incarcerated individuals, in addition to the substantial mental health benefits (see x, x, x) associated with contact with nature.]

The lupines needed the kind of upland prairie that’s now hard to find in the valley where they once flourished because of the native Kalapuya people’s regular cultural burning of the meadows.

While it sounds counterintuitive to burn a meadow to increase numbers of flowers and butterflies, grasses and forbs [a.k.a. herbs] become too dense in the absence of such disturbances, while their fine soil building eventually creates ideal terrain for woody shrubs, trees, and thus the end of the grassland altogether.

Fender’s blue caterpillars produce a little bit of nectar, which nearby ants eat. This has led over evolutionary time to a co-dependent relationship, where the ants actively protect the caterpillars. High grasses and woody shrubs however prevent the ants from finding the caterpillars, who are then preyed on by other insects.

Now the Confederated Tribes of Grand Ronde are being welcomed back onto these prairie landscapes to apply their [traditional burning practices], after the FWS discovered that actively managing the grasslands by removing invasive species and keeping the grass short allowed the lupines to flourish.

By restoring the lupines with sweat and fire, the butterflies have returned. There are now more than 10,000 found on the buttes of the Willamette Valley."

-via Good News Network, November 28, 2022

#butterflies#butterfly#endangered species#conservation#ecosystem restoration#ecosystem#ecology#environment#older news but still v relevant!#fire#fire ecology#indigenous#traditional knowledge#indigenous knowledge#lupine#wild flowers#plants#botany#lepidoptera#lepidopterology#entomology#insects#good news#hope

4K notes

·

View notes

Text

On the Sioux Valley Dakota Nation west of Brandon, Man., schoolchildren are throwing pumpkins into a bison pen, a ceremony and sign of respect to an animal that has deep spiritual significance for Indigenous culture and identity.

Community leaders are also educating a new generation about how the bison, known in these parts as buffalo, has important implications for the future of the Prairies – rehabilitating natural grasslands and conserving water in a time of climate change.

"The significance of the buffalo goes back hundreds of years. These animals have saved our lives," said Anthony Tacan, a band councillor whose family is the keeper of this herd.

"They provided food and weapons out of the bones, tools, the hides for clothing, the teepees. It did everything for us. So going forward, we decided it's our turn to give back. It's our turn to look after them."

Continue Reading

#cdnpoli#canadian politics#canada#canadian news#sioux valley dakota nation#first nations#indigenous#american buffalo#american bison#bison#ecology#ecosystem restoration#manitoba

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

North America once housed more beavers than humans — by a lot. Even before Europeans showed up and built an entire extractive economy on beaver pelts, estimates put the number in the hundreds of millions (during the Pleistocene, there were even giant species of beaver, as large as bears). The North American fur trade, which lasted for centuries, nearly wiped beavers off the continent — and, unknown to trappers, vastly changed its ecosystems from sea to sea.

“There is evidence that riverscapes across the West were much more complex and ‘anastomosed’ prior to European colonization,” says Nicholas Kolarik, a Ph.D. student working with Brandt, who is focusing on mapping data sets of wetlands. Anastomosis denotes branches connecting two things, like organs in the body, but in this case, he means streams, since waterways in the U.S. West used to be much more interconnected.

Today, they’re “starved of wood,” he says, but by adding wood into streams and rivers, especially by building dams, beavers slow water down significantly.

“In doing so, sediment is stored, water infiltrates into the aquifers, riparian vegetation establishes, habitat is created, and carbon is stored,” Kolarik says.

[...]

“Beavers maintain healthy riverscapes which store carbon and water. Consistent access to water is key to mitigating the effects of climate disturbances like drought.”

Beavers’ role as firefighters has already been documented in Idaho. A 2018 technical report by Anabranch Solutions, a river restoration company, found that beavers were a major factor in decreasing burn intensity along Baugh Creek during that year’s Sharps Fire.

“Where active beaver dams were present, native riparian vegetation persisted, unburnt,” the authors wrote. In our hotter and fierier world, beavers are a buffer.

435 notes

·

View notes

Text

Solarpunk Sunday Suggestion:

Educate yourself about the importance of peatland and mangrove ecosystems

#solarpunk#hopepunk#environmentalism#cottagepunk#social justice#community#optimism#bright future#climate justice#tidalpunk#lunarpunk#turbinepunk#ecosystem restoration#carbon sinks#mangroves#peat#wetlands#bog#coast#solarpunksundays

69 notes

·

View notes

Text

Romanticise ecosystem restoration

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

Beaver dam on an abandoned road, NJ/NY Border - March 8 2024

#love how beavers can restore ecosystems by just placing logs everywhere#even though its a road theres still salamanders#which means that its a clean waterway#photographers on tumblr#nature#original photography#forest#ecosystem restoration#njlocal#new jersey#winter#destroyed and abandoned

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

Saving Brazil's golden monkey, one green corridor at a time

20 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Urgency of National Wildlife Week: A Call to Action for Biodiversity Preservation

View On WordPress

#advocacy#afforestation#afforestation areas#biodiversity#Buddy System#Citizen Science#citizen scientists#City Nature Challenge Events#Climate Action#climate change#Community Empowerment#Community Engagement#conservation#conservation awareness#Conservation Efforts#conservation initiatives#Eco-Quest Projects#ecological balance#Ecological preservation#Ecological Restoration#ecosystem health#Ecosystem Restoration#endangered species#Energy Use#environmental awareness#environmental challenges#environmental conservation#Environmental Education#environmental impact#Environmental Management

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Forests do more for the climate than store and sequester carbon.

For example, they:

regulate rainfall

provide cooling benefits

protect coastal areas

provide forest products for local communities facing climatic threats

#Adaptation services from forests#Adaptation and resilience from forests#ecosystem restoration#biodiversity conservation#integrated risk mamagement#water regulation#livelihood diversification#urban climate benefits#Protection from hazards#fao forestry#FAO CLIMATE#sdg15

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Klamath River’s salmon population has declined due to myriad factors, but the biggest culprit is believed to be a series of dams built along the river from 1918 to 1962, cutting off fish migration routes.

Now, after decades of Indigenous advocacy, four of the structures are being demolished as part of the largest dam removal project in United States history. In November, crews finished removing the first of the four dams as part of a push to restore 644 kilometres (400 miles) of fish habitat.

“Dam removal is the largest single step that we can take to restore the Klamath River ecosystem,” [Barry McCovey, a member of the Yurok Tribe and director of tribal fisheries,] told Al Jazeera. “We’re going to see benefits to the ecosystem and then, in turn, to the fishery for decades and decades to come.” ...

A ‘watershed moment’

Four years later, [after a catastrophic fish die-off in 2002,] in 2006, the licence for the hydroelectric dams expired. That created an opportunity, according to Mark Bransom, CEO of the Klamath River Renewal Corporation (KRRC), a nonprofit founded to oversee the dam removals.

Standards for protecting fisheries had increased since the initial license was issued, and the utility company responsible for the dams faced a choice. It could either upgrade the dams at an economic loss or enter into a settlement agreement that would allow it to operate the dams until they could be demolished.

“A big driver was the economics — knowing that they would have to modify these facilities to bring them up to modern environmental standards,” Bransom explained. “And the economics just didn’t pencil out.”

The utility company chose the settlement. In 2016, the KRRC was created to work with the state governments of California and Oregon to demolish the dams.

Final approval for the deal came in 2022, in what Bransom remembers as a “watershed moment”.

Regulators at the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) voted unanimously to tear down the dams, citing the benefit to the environment as well as to Indigenous tribes...

Tears of joy

Destruction of the first dam — the smallest, known as Copco 2 — began in June, with heavy machinery like excavators tearing down its concrete walls.

[Amy Cordalis, a Yurok Tribe member, fisherwoman and lawyer for the tribe,] was present for the start of the destruction. Bransom had invited her and fellow KRRC board members to visit the bend in the Klamath River where Copco 2 was being removed. She remembers taking his hand as they walked along a gravel ridge towards the water, a vein of blue nestled amid rolling hills.

“And then, there it was,” Cordalis said. “Or there it wasn’t. The dam was gone.”

For the first time in a century, water flowed freely through that area of the river. Cordalis felt like she was seeing her homelands restored.

Tears of joy began to roll down her cheeks. “I just cried so hard because it was so beautiful.”

The experience was also “profound” for Bransom. “It really was literally a jolt of energy that flowed through us,” he said, calling the visit “perhaps one of the most touching, most moving moments in my entire life”.

Demolition on Copco 2 was completed in November, with work starting on the other three dams. The entire project is scheduled to wrap in late 2024.

[A resilient river]

But experts like McCovey say major hurdles remain to restoring the river’s historic salmon population.

Climate change is warming the water. Wildfires and flash floods are contaminating the river with debris. And tiny particles from rubber vehicle tires are washing off roadways and into waterways, where their chemicals can kill fish within hours.

McCovey, however, is optimistic that the dam demolitions will help the river become more resilient.

“Dam removal is one of the best things we can do to help the Klamath basin be ready to handle climate change,” McCovey explained. He added that the river’s uninterrupted flow will also help flush out sediment and improve water quality.

The removal project is not the solution to all the river’s woes, but McCovey believes it’s a start — a step towards rebuilding the reciprocal relationship between the waterway and the Indigenous people who rely on it.

“We do a little bit of work, and then we start to see more salmon, and then maybe we get to eat more salmon, and that starts to help our people heal a little bit,” McCovey said. “And once we start healing, then we’re in a place where we can start to help the ecosystem a little bit more.”"

-via Al Jazeera, December 4, 2023

#indigenous#river#riverine#ecosystem#ecosystem restoration#klamath#klamath river#oregon#california#yurok#fishing#fisheries#nature is healing#literally this time lol#united states#dam removal#climate change#conservation#sustainability#salmon#salmon run#water quality#good news#hope#rewilding#ecology#environment

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

I may be an overly ambitious undergrad, but I feel like I just had an actual eureaka moment for rehabilitating the local river, one of the most polluted in the nation. Who knows if it'll actually go anywhere, but if it does, I'd make me feel a lot better about how my direct ancestors fucked up the local ecosystem 100 years ago. Call it white-guilt, but I genuinely am doing this particular pathway to palaeontology; via communication, ecology and enviro science, so I have at least SOMETHING substantial to give back to my homeland before I move on to my dream job. I hope this works.

4 notes

·

View notes

Link

When bison were allowed to graze through patches of tallgrass prairie, they boosted native plant species richness by a whopping 86 percent over the past three decades, according to a study published August 29 in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Areas grazed by cattle also benefited native species, though they increased by just 30 percent. American bison, also called buffalo, provided nearly three times the environmental benefit as cows, and researchers aren’t yet sure why.

“We’re still kind of surprised at just how large of an effect bison had,” says study leader Zak Ratajczak, an ecologist at Kansas State University. “I don’t think anyone would have predicted this ahead of time.”

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

About the Carpathian Mountains Initiative which provide a regional approach to protect wilderness, and maintain the connectivity of crucial habitats.

Spanning the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia and Ukraine, the Carpathian Mountains represent one of the last great wilderness areas in Europe. The Carpathian Mountains Initiative, under the Carpathian Convention, works with communities and local and national authorities to provide a regional approach to protect this wilderness, and maintaining the connectivity of crucial habitats for some of Europe’s largest mammals, including the brown bear, the bison, the wolf and lynx. It also acts to protect old growth forest, of which the region hosts some of the last remaining examples, and to support the economic activities of the mountain ecosystems so that they can develop in a sustainable way. The project has so far seen important reductions in bear and wolf road deaths, saved 6,500 hectares of old growth forests in the Slovak Carpathians and seen tourism grow in rewilding areas.

#trees and forests#degraded forests#environment#natural habitats#carpathianconvention#ecosystem restoration#restoring ecosystems#initiatives#carpathians#rewilding areas#Czech Republic#Hungary#Poland#Romania#Serbia#Slovakia#ukraine#Carpathian Mountains

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

Americans, let's get on it. It's easy, I promise.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Riparian Restoration at New Bolton - November 19th 2023

6 notes

·

View notes