#emily post

Text

LOONEY TUNES BOOKS

11 notes

·

View notes

Quote

The one in greatest danger of making enemies is the man or woman of brilliant wit. If sharp, wit tends to produce a feeling of mistrust even while it stimulates. Furthermore, the applause which follows every witty sally becomes in time breath to the nostrils, and perfectly well-intentioned people, who mean to say nothing unkind, in the flash of a second “see a point,” and in the next second score it with no more power to resist than a drug addict has to refuse a dose put into his hand!

Emily Post, Dangers to Be Avoided, 1945

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, women had to bare their shoulders in order to eat at formal dinners. They also had to put on long gloves, only to remove them before the meal began. Buttoned, elbow-length gloves could be so hard to get off that one could buy a pair with hands that rolled back. The etiquette manuals were never very sure whether they approved of this labour-saving device; Emily Post pronounced it “hideous.”

Gloves, once removed, had to join evening bag, fan, and large damask napkin, all precariously balanced on a slippery, possibly satin-sheathed, lap. Emily Post suggested rather daringly (“ this ought not to be put into a book of etiquette, which should say you must do nothing of the kind”) that one might cover all these objects with the napkin placed cornerwise across the knees “and tuck the two side corners under like a lap robe, with the gloves and the fan tied in place, as it were.”

She went further, since one could no longer count on receiving a very large napkin, and promoted the carrying of paper clips, by gentlemen as well as ladies, to hold the napkin in place. All this assumes that a civilized diner would never require any dabbing at the lips with a napkin during dinner.

Until quite recently women kept their hats on in restaurants and when invited to a formal lunch. Liselotte, a French arbiter of etiquette, says in 1915 that women may keep their hats on even if the lunch is not very ceremonious “so as not to derange the edifice of their hair,” and so that they can leave after the meal without having to recreate their toilette.

But a hostess, who had not had to go out, could remain hatless, even at formal functions. It has usually been the case that hosts, because they are at home and also because they are ritually more powerful, could wear less formal clothes than guests. A hostess never wore gloves or a face veil in her own home, “unless,” Emily Post added jocularly but rather brutally in 1922, “there is something the matter with her face.” Guests wearing face veils were allowed to fasten the lower edge “up over their noses.”

1 note

·

View note

Text

Vintage Living Tip No. 33: Why practice good manners?

#vintage tips#vintage blogger#vintage lifestyle#vintage life#vintage#vintage style#vintage asthetic#vintage advice#emily post#vintage manners#good manners#ladylike#vintage housewife

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

emily gwen, the creator of the sunset lesbian flag that we’ve come to commonly use, still continues to live in poverty.

multi-billion dollar companies have used their design and made profit from it, and yet they have not seen a cent for their creation.

i’ve been friends with emily for years, and i have not once seen them be financially stable the entire time. i’ve seen them homeless, unemployed, starving. right now, they need our help more than ever.

please consider donating to emily’s ko-fi, especially if you’ve used their design to create something and profited from it.

#emily’s finally found housing after couch surfing at friends’ places for months#they’ve got a lot of debt rn on top of bills and rent#rn they don’t have food in the house and they’re starving#they don’t deserve this at all they are so kind and i literally hate to see them suffering#please please pleaaase donate and reblog#they don’t ask for much but they deserve the world#mutual aid#crowdfunding#donation post#belle speaks

29K notes

·

View notes

Text

I've been trying to read about maids (and other servants), both as a personal interest and research for a work of fiction ive been drafting and redrafting for a long time. One of the first things I've read to that end is the original 1922 edition of Emily Post (Etiquette In Society, In Politics, and at Home). I'm not finished reading it, but it's been a very interesting look into 1920's high society- both by what the author puts proudly on paper, and what she suggests as a matter of course. For instance, there is a lot of humor in it where she might say something fairly clever or witty, but you can also tell that half the examples of "what you shouldn't do" are just poorly disguised attacks on people she personally despises in her own life. Also you get to see where the author brazenly exposes her classism/racism/misogyny, and the subtle ways those things are revealed just by nature of the social structure she is prescribing.

Anyway, I thought I'd post my thoughts on the chapter most devoted to a housekeeping staff (which is chapter 12, The Well Appointed House). This is a somewhat long post so more below the cut if you're interested! I'm afraid I'm not much of a historian, so my thoughts are rather brief, but I hope it's interesting anyway.

Every house has an outward appearance to be made as presentable as possible, an interior continually to be set in order, and incessantly to be cleaned. And for those that dwell within it there are meals to be prepared and served; linen to be laundered and mended; personal garments to be brushed and pressed; and perhaps children to be cared for. There is also a door-bell to be answered in which manners as well as appearance come into play.

The personality of a house is indefinable, but there never lived a lady of great cultivation and charm whose home, whether a palace, a farm-cottage or a tiny apartment, did not reflect the charm of its owner. Every visitor feels impelled to linger, and is loath to go. Houses without personality are a series of rooms with furniture in them. Sometimes their lack of charm is baffling; every article is "correct" and beautiful, but one has the feeling that the decorator made chalk-marks indicating the exact spot on which each piece of furniture is to stand. Other houses are filled with things of little intrinsic value, often with much that is shabby, or they are perhaps empty to the point of bareness, and yet they have that "inviting" atmosphere, and air of unmistakable quality which is an unfailing indication of high-bred people.

The subject of furnishings is however the least part of this chapter—appointments meaning decoration being of less importance (since this is not a book on architecture or decoration!), than appointments meaning service.

While the bulk of this chapter is devoted to detailing the structure of a house staff, and how best you (a well bred lady) should manage that staff, the chapter begins with advice on how to furnish your house in good taste. While this didn't immediately occur to me on the first read, I think it says quite a bit about the attitude of the author that "the things in your house" and "the people you employ to maintain those things" are lumped into the same category.

In very "beautifully done" houses (all the dresses of the maids are furnished them), the color of the uniforms is chosen to harmonize with the dining-room. At the Gildings', Jr., for instance, where there are no men servants because Mr. Gilding does not like them, but where the house is as perfect as a picture on the stage, the waitress and parlor-maid wear in the blue and yellow dining-room, dresses of Nattier blue taffeta with aprons and collars and cuffs of plain hemstitched cream-colored organdie, that is as transparent as possible; blue stockings and patent leather slippers with silver buckles, their hair always beautifully smooth. Sometimes they wear caps and sometimes not, depending upon the waitress' appearance. Twenty years ago, every maid in a lady's house wore a cap except the personal maid, who wore (and still does) a velvet bow, or nothing. But when every little slattern in every sloppy household had a small mat of whitish Swiss pinned somewhere on an untidy head, and was decked out in as many yards of embroidery ruffling on her apron and shoulders as her person could carry, fashionable ladies began taking caps and trimmings off, and exacting instead that clothes be good in cut and hair be neatly arranged.

A few ladies of great taste dress their maids according to individual becomingness; some faces look well under a cap, others look the contrary. A maid whose hair is rather fluffy—especially if it is dark—looks pretty in a cap, particularly of the coronet variety. No one looks well in a doily laid flat, but fluffy fair hair with a small mat tilted up against a knot of hair dressed high can look very smart. A young woman whose hair is straight and rebellious to order, can be made to look tidy and even attractive in a headdress that encircles the whole head. A good one for this purpose has a very narrow ruche from 9 to 18 inches long on either side of a long black velvet ribbon. The ruche goes part way, or all the way, around the head, and the velvet ribbon ties, with streamers hanging down the back. On the other hand, many extremely pretty young women with hair worn flat do not look well in caps of any description—except "Dutch" ones which are, in most houses, too suggestive of fancy dress. If no caps are worn the hair must be faultlessly smooth and neat; and of course where two or more maids are seen together, they must be alike. It would not do to have one wear a cap and the other not.

To continue that thought, maids and dolls do have a lot in common, I suppose. As a side note, the author uses pseudonyms for some of her close friends when she is discussing specific examples, I wonder if a contemporary reader would easily be able to determine who she is writing about or not. Anyway, this section particularly sickens me, with reference to Mr. Gilding and his preferences. This detail is thrown in, as an afterthought, but leaves so much misogyny unsaid. Maybe Mr. Gilding doesn't need a valet, and would feel gay having some guy picking out his clothes or whatever. But why should that preference extend to the rest of the staff? Etiquette is full of little surprises like this. To continue with this train of thought of maids as an extension of the self-

The well-bred maid instinctively makes little of a guest's accident, and is as considerate as the hostess herself. Employees instinctively adopt the attitude of their employer.

Regardless,

Are maids allowed to receive men friends? Certainly they are! Whoever in remote ages thought it was better to forbid "followers" the house, and have Mary and Selma slip out of doors to meet them in the dark, had very distorted notions to say the least. And any lady who knows so little of human nature as to make the same rule for her maids to-day is acting in ignorant blindness of her own duties to those who are not only in her employ but also under her protection.

At least Post is not advocating for this kind of control over the lives of her staff, but now we know this happens often enough it needed to be remarked on.

Unless he is an old-time colored servant in the South a butler who wears a "dress suit" in the daytime is either a hired waiter who has come in to serve a meal, or he has never been employed by persons of position; and it is unnecessary to add that none but vulgarians would employ a butler (or any other house servant) who wears a mustache! To have him open the door collarless and in shirt-sleeves is scarcely worse!

I'm not so equipped to dissect this passage, as I'm admittedly not so equipped with the context a contemporary reader would have with how this comparison is meant to come across, but it doesn't feel like its a very flattering one at all. Again, I'm not really well equipped to be doing a deep dive on this. So while the above passages reveal the author's attitude subtly, those below I feel do it directly. I present them without comment.

A rule can't be given because there isn't any. As said in another chapter, a well-bred person always lives within the walls of his personal reserve, a vulgarian has no walls—or at least none that do not collapse at the slightest touch. But those who think they appear superior by being rude to others whom fortune has placed below them, might as well, did they but know it, shout their own unexalted origin to the world at large, since by no other method could it be more widely published.

But before going into the various details of service, it might be a good moment to speak of the unreasoning indignity cast upon the honorable vocation of a servant.

There is an inexplicable tendency, in this country only, for working people in general to look upon domestic service as an unworthy, if not altogether degrading vocation. The cause may perhaps be found in the fact that this same scorning public having for the most part little opportunity to know high-class servants, who are to be found only in high-class families, take it for granted that ignorant "servant girls" and "hired men" are representative of their kind. Therefore they put upper class servants in the same category—regardless of whether they are uncouth and illiterate, or persons of refined appearance and manner who often have considerable cultivation, acquired not so much at school as through the constant contact with ultra refinement of surroundings, and not infrequently through the opportunity for world-wide travel.

And yet so insistently has this obloquy of the word "servant" spread that every one sensitive to the feelings of others avoids using it exactly as one avoids using the word "cripple" when speaking to one who is slightly lame. Yet are not the best of us "servants" in the Church? And the highest of us "servants" of the people and the State?

To be a slattern in a vulgar household is scarcely an elevated employment, but neither is working in a sweat-shop, or belonging to a calling that is really degraded; which is otherwise about all that equal lack of ability would procure. On the other hand, consider the vocation of a lady's maid or "courier" valet and compare the advantages these enjoy (to say nothing of their never having to worry about overhead expenses), with the opportunities of those who have never been out of the "factory" or the "store" or further away than the adjoining town in their lives. As for a nurse, is there any vocation more honorable? No character in E.F. Benson's "Our Family Affairs" is more beautiful or more tenderly drawn than that of "Beth," who was not only nurse to the children of the Archbishop of Canterbury but one of the most dearly beloved of the family's members—her place was absolutely next to their mother's in the very heart of the household always.

Two years ago, Anna, who had for a lifetime been Mrs. Gilding's personal maid, died. Every engagement of that seemingly frivolous family was cancelled, even the invitations for their ball. Not one of the family but mourned for what she truly was, their humble but nearest friend. Would it have been so much better, so much more dignified, for these two women, who lived long useful years in closest association with every cultivating influence of life, to have lived on in their native villages and worked in a factory, or to have had a little store of their own? Does this false idea of dignity—since it is false—go so far as that?

Thank you for reading! There is a lot more one could discuss in that chapter, some of which I initially included but left out. I might return to this, after reading the full text, or if people are curious about it.

Oh, and you can read the full text yourself here on Project Gutenberg!

1 note

·

View note

Text

okay so picture this.

You're a man named Jim Steinman. You are one of the most prolific songwriters of the 80s. In your spirit, output and essence, you are eternally popping a wheelie on a motorcycle while a hot half-naked woman clings to you and bats wheel in the sky above.

You wrote a song in which Meatloaf plays a hideously disfigured hunk who steals a nubile lady back to his crumbling manor and introduces her to the pleasures of magic lesbian group sex.

You wrote a song in which Celine Dion sings as Heathcliff from Wuthering Heights, dancing with Cathy's corpse on a beach in the moonlight; a scene which you, Jim Steinman, believe should have been in the book. (The moors of Wuthering Heights are landlocked, but you, Jim Steinman, are too fucking real to care about that.)

You wrote the song for the opening scene of the movie Streets of Fire, in which evil leatherdaddy Willem Dafoe leads his malefic motorcycle crew into a concert to abduct Diane Lane while she's wearing a skintight satin jumpsuit.

You wrote a song in which Bonnie Tyler wanders a haunted boarding school as literal demon twinks gyrate at her out of the fog.

There is no peak of goth camp that you, Jim Steinman, have not summited, no horny energy you have not tapped. They say that Alexander the Great wept when he saw there were no more worlds to conquer. But you, Jim Steinman, are not Alexander the Great. You, Jim Steinman, are better. You, Jim Steinman, have vision.

You take your most successful song, the song everyone knows, the most big-haired, white dress, gothic arches, doves flying, possessed choir boys chanting, bombastic song you have, and think: what if this, but with vampires.

And so you change the lyrics to be about death and infinity and a powerful bloodsucking lord seducing a girl who is ALL ABOUT IT, and then toss off a whole musical for this song to be the centerpiece to, and the musical is bad but it's also a weird hit that's been staged in fourteen countries and revived seven times, because nothing has ever whipped as campily, as ridiculously, as perfectly as this:

youtube

It never takes off in America. A prophet is without honor in his own land. But that doesn't matter. How could it matter? You are perhaps the most creatively self-actualized man who has ever lived. Look at that vampire. He's coming in hot and a hundred Venetian nuns gave their lives to make his ludicrously capacious lace sleeves. Look at that girl. She was born in a fog machine. She wore her best red velvet cape. She's down bad. She's singing Total Eclipse of the Heart the whole time.

You are Jim Steinman, and you have reached apotheosis.

#reading this post is like doing a line of coke if the line of coke was my entire personality#emily does musicals

10K notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy deathday to Emily Post. And I better get a fucking thank-you note this time!!

0 notes

Text

Not one person has mentioned marcille’s fucking breath hitch/quiver in the dub. Im literally foaming at the mouth.

#EVERYONE SAY THANK YOU EMILY RUDD#i am also upset that the ressurection scene did not live up to our expectations#but for now lets all enjoy the fact that the anime made it obvious that marcille only freaked out bc falin was using her mana#and not bc it was getting gay#farcille#dungeon meshi#delicious in dungeon#dungeon meshi spoilers#marcille donato#falin touden#my posts

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

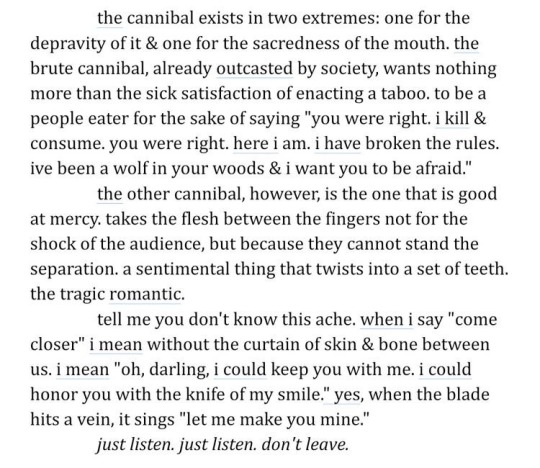

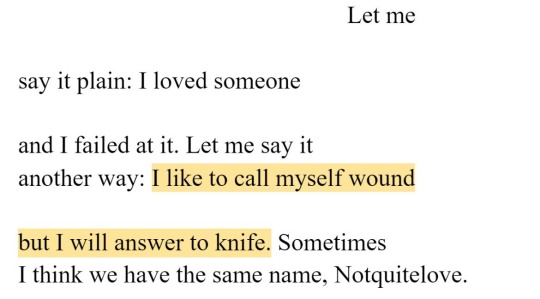

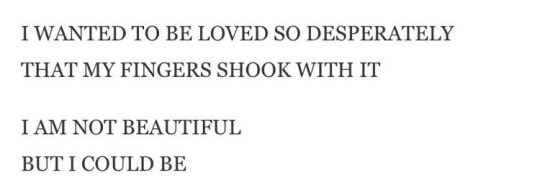

KILL ME IF IT'S WORTH IT; ON FLESH.

silas denver melvin // ethel cain // george bataille // blythe baird // margaret atwood // nicole homer // emily palermo.

#sorry 2 silas denver melvin for having to endure all the posts where he's mentioned </3#on flesh#web weaving#silas denver melvin#ethel cain#george bataille#blythe baird#margaret atwood#nicole homer#emily palermo#writing#poetry#webweaving#quotes

9K notes

·

View notes

Text

genuinely i think it's important for adults, especially in the plague times, to play pretend in our day-to-day lives. when i rub my back down with tiger balm so i can sleep without pain, i imagine i am a valiant knight tending to an old injury i received from a dragon. when i go to the store to pick up eggs and milk, i am a lone cowboy riding into town on a mission. when i turn my collar up against the wind i am a femme fatale who's killed 4 husbands and is scoping out a 5th. when i stomp around in the snow i am a doomed polar explorer. if being a little bit silly about my walk to the pharmacy helps me remember that life can be full of joy and whimsy, then so be it.

#this is a pointless text post#my most embarrassing version of this is that whenever it was foggy at the lighthouse i imagined i was emily bronte#or that i was taking a walk in the fog with my good friend emily bronte :^)#so much of this is also tied into the fact that my body hurts all the goddamn time#i am trying to make my pain something i can live with#is this gonna be how i learn that normal people don't daydream about being In The Past#anyway do u guys imagine these sort of scenarios too or am i just a freak#greatest (s)hits

19K notes

·

View notes

Text

I liked the new episodes.

5K notes

·

View notes

Text

Hey erm.... is Tumblr actually scaling images down in the app now...?

#edit: if ur getting only the first part of this post on ur dash. pls consider that maybe there are other parts to a post with 10k+ notes#woes of emily#i will rb with an experiment

21K notes

·

View notes

Quote

After living for half a century, it would seem only reasonable in all that time to have learned something of life; to have felt some things deeply; to have enjoyed and suffered; to have succeeded in this, failed in that, and – – through darker hours far more likely than through light ones – – to have acquired a depth of sympathetic understanding, as impossible to youth as for fifty to have the skin of fifteen. Why, oh why, then, does “fifty” focus its entire mind on complexion?

Emily Post, 1932

0 notes

Text

It has been the rule until recently in our own culture, and it still is the tendency, to ask an equal number of men and women. The convention itself is fairly recent, because respectable women have tended not to be invited to men’s dinner parties during most of human history.

Hosts have had to keep lists on hand of unattached people who could be invited to fill a gap where somebody, and especially a woman, lacked a “partner.”

The problem was compounded, of course, if a party of fourteen lost a guest: it was imperative that someone be found, to keep thirteen from sitting down to table. An institution called the quatorzièmes (“ fourteenths”) existed in nineteenth-century Paris. These were men who waited at home between 5: 00 and 9: 00 p.m. every night, all dressed up and ready to step into the breach where any dinner party threatened suddenly to number thirteen. You could hire a presentable, experienced “fourteenth” whenever you needed one.

Lady Sybil Colefax, a London hostess famous in the 1920s and 1930s, was capable of writing hundreds of dinner invitations in a month. She wrote them at home, in trains, at every spare moment, just as a different kind of woman would never waste time while she could be knitting.

Colefax invitations would pour in to people whose company was greatly in demand. “Resistance was futile,” Brian Masters writes. “… She simply issued another, and another, she would mount up scores of them if necessary, until the prey eventually succumbed, like a fox pursued by hounds, through sheer weariness.”

Her nearly illegible handwriting was famous. People used to puzzle over their invitations for days, trying to make out when they were supposed to appear for dinner, and who the other guests would be. “One usually placed the card on a mantelpiece and glanced at it from time to time, hoping that its secrets would suddenly be revealed; or threw it on the floor in the hope that the odd angle would make all clear.”

But very soon they would have to reply. The guest’s obligation is in the very first place to reply, as soon as possible. Hosts should be told within days—the Victorians made that twenty-four hours—whether guests will be coming or not, so that substitute invitations can be issued to similarly dazzling people. Once an invitation has been accepted, it must at all costs be honoured. “Nothing,” wrote Emily Post, “but serious illness or death or an utterly unavoidable accident.

#book: the rituals of dinner#Emily Post#culture#upper classes#Lady Sybil Colefax#1930s#1920s#20th century#victorian era

0 notes