#environmental history

Text

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

“The extinction of the great auk took place in real time and under the watchful eyes of European naturalists even as the fate of the famous dodo still puzzled them. Gísli Pálsson brilliantly explores the cultural climate in which the idea of human-induced extinction became accepted as scientific fact. Pálsson’s elegantly written historical ethnography tells a story that unites the settled ecological past, the ambivalent present, and the probable future.”

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

“....the expansion of the artificial swimming pool system [occurred] in the context of increasingly polluted waterfronts. The growth of cities could crowd out and damage the spaces in which public swimming took place. One response to the bacteriological revolution - the extension of sewers to remove dangerous germs from all home environments - generated a public health crisis, by transporting bacteria to the places where citizens might swim. Concerns about water quality, and the ability to quantity it, both prompted and complicated efforts to find healthy places to swim in industrial cities.

....the development of Hamilton [Ontario’s] municipal swimming pool system [was situated] in the context of the environmental degradation of the industrial city as its commitment to economic expansion compromised an aspect of public health. Like the construction of the city’s elaborate water supply and purification systems, the building of swimming pools allowed city officials to continue using Hamilton’s bay [on Lake Ontario] as a sink for residential and industrial wastes, and to do so without significant investments in wastewater treatment facilities. Until the Second World War, Hamilton’s city leaders and medical authorities confidently believed that they could identify, delineate, and construct safe swimming areas along the shores of their harbour, and supplement them with a few public swimming pools. After the war, however, they abandoned their efforts altogether. For those who could not flee the city for clearer waters of northern lakes [because they could not afford to], municipal authorities offered artificial swimming pools as the only healthy place to swim locally. ...while swimming pools reflected a number of social and cultural values, they must be recognized chiefly as a technological fix for an urban public health crisis. Artificial pools for swimming allowed Hamilton’s city leaders to abandon the natural waters of the bay and the public beaches frequented by the working class to the effluent left by “the constructive power of the profit motive.””

- Nancy Bouchier and Ken Cruikshank, “Abandoning Nature: Swimming Pools and Clean, Healthy Recreation in Hamilton, Ontario, c. 1930s-1950s,” Canadian Bulletin of Medical History Volume 28:2, 2011: p. 318-319

#hamilton#public swimming pools#public beaches#swimming pool#environmental history#pollution#history of pollution#public health#industrial production#history of health care in canada#parks and recreation#history of recreation in canada#public spaces#academic quote#canadian history#lake ontario#great lakes

215 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Just read this great journal article by Simon Farley about Australian brumbies (’feral’ horses). The way advocacy for them has been intentionally hyper emotional, used by settler people to frame themselves as victims and assert their sense of ownership over land.

#animal history#environmental history#colonialism#this is the first thing i do after getting my new uni email#and getting access to a public library lol#my readings

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Rise of the American Conservation Movement: Power, Privilege, and Environmental Protection

by Dorceta Taylor (2016)

In this sweeping social history Dorceta E. Taylor examines the emergence and rise of the multifaceted U.S. conservation movement from the mid-nineteenth to the early twentieth century. She shows how race, class, and gender influenced every aspect of the movement, including the establishment of parks; campaigns to protect wild game, birds, and fish; forest conservation; outdoor recreation; and the movement's links to nineteenth-century ideologies. Initially led by white urban elites—whose early efforts discriminated against the lower class and were often tied up with slavery and the appropriation of Native lands—the movement benefited from contributions to policy making, knowledge about the environment, and activism by the poor and working class, people of color, women, and Native Americans. Far-ranging and nuanced, The Rise of the American Conservation Movement comprehensively documents the movement's competing motivations, conflicts, problematic practices, and achievements in new ways.

About the second image

I've been listening to a zillion podcasts this year, and heard about the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative. The movement (and legal/political shifts) toward overturning the white supremacist underpinnings of much of North American conservation has been building, which is exciting.

There is a virtual film fest on Fri Nov 24th https://y2y.net/event/y2y-wild-film-fest-creating-connections/

Spanning five American states, two Canadian provinces, two Canadian territories, and at least 75 Indigenous territories, the Yellowstone to Yukon region is unlike any other in the world. This incredible landscape of over half a million square miles — or 1.3M square kilometers — represents the most intact large mountain region in North America.

1 note

·

View note

Link

Silent Spring adeptly critiqued the American chemical industry and federal regulation of toxic chemicals at a time when many people’s faith in them was nearly unshakeable. She did so by placing humans within the web of ecology, rather than outside it.

This move challenged long-held notions that science allowed humans to control—and thereby live apart from—nature. Carson asked readers, “whether any civilization can wage relentless war on life without destroying itself,” because humans were inherently reliant on other organisms for their own survival.

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Worldbuilding: Some Writing References On The Little Ice Age

A reader asked for a list of what I was reading recently for an Idea. Specifically, someone dumped into a fantasy version of the 1600s near Korea. (The poor guy.) So I started pulling it together....

Er. It was a lot longer than I thought.

So. What I’ve read in the past or currently related to this includes....

Ancient Inventions, by Peter James. Ranges across the world and history up to the Middle Ages, never a lot of details but plenty of pics, and there’s bits on acupuncture, how old sewing is, and why before steam engines you wanted a waterwheel near a mine, if you could.

Several books by Conrad Totman: Early Modern Japan. Japan: An Environmental History. The Green Archipelago: Forestry in Preindustrial Japan. These books aim for an environmental slant, but they also end up covering a lot of daily life and political maneuvers because, guess what, what people do that way affects the environment! Also he is an excellent writer, with good flow.

The Culture of Civil War in Kyoto, by Mary Elizabeth Berry. Warning, this one can be a bit dark, a lot of people died in the Warring States Era, and the attitude of survivors of a whole century-plus of constant war was sometimes not healthy.

Samurai William: The Englishman Who Opened Japan, by Giles Milton. Focuses on our sailor, but gets into Japanese politics versus the rest of the world, and how that worked out for the English, Portuguese, and Dutch who wanted to trade. (The Dutch won for a lot of reasons, but mainly because they were smart enough to bring wanted products instead of broadcloth, and kept religion out of it.)

1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created, by Charles C. Mann. Have read from local libraries, sometime want to get a reference copy. Covers the ecological consequences of Columbus and everyone sailing after him, with consequences that rocked around the world as new plants, animals, and diseases spread.

A book on a Japanese diving village which I cannot find the name for, darn it. For all I know it was a very small press thing; it was in an EPA library, of all places. It was black-and-white photography of the people, what they did, and how they lived. Maybe 60-odd pages? If you ever read my fanfic “Shadows in Starlight” and wondered where I got the fishing village that saved Obi-Wan and Kenshin out of a scrape, it’s from this book, as well as the next one.

Fishing Villages in Tokugawa Japan, by Arne Kalland. Unfortunately, this one appears to be out of print. I hope my copy made it through the move. A lot of dry anthropological detail, but it covers how plain old ordinary fisherfolk lived in those times, including their farming and salt-making.

Everyday Life in Joseon Korea. Got this a couple months ago; it’s a translated collection of essays by Korean historians, and is Exactly What It Says On The Tin. It’s got a whole farming calendar, things people ate, how they traded, how they made salt, why you wanted to be a translator if you could, and a bunch of political shenanigans to boot.

Ginseng and Borderland, by Seonmin Kim. Also a recent acquisition. Mostly about the Joseon Dynasty’s interactions with the Qing Empire, and how they leveraged being a dependent kingdom in a kind of political judo to keep Chinese armies off their border. So a little later than I’m aiming, but it does bring up “what the situation was in Ming before things got messy”. And it’s about ginseng, and the lengths people go to get it, and that is just plain interesting.

Side note here: If you study biogeography at all, there is an interesting biological hiccup in what species are where that no one’s quite pinned down the reason for yet. In short: there are a lot of species in Eastern Asia (including Japan) that have related species in the Southeastern U.S. For example, while crocodiles are across the globe, there are only two species of alligators: American and Chinese. There are three species of wisteria; Chinese, Japanese, and American. And depending who you ask, there are only two or three species of ginseng. Native to - have you guessed yet? - East Asia, historically Manchuria/Northern Korea... and the one in the Appalachians (also in Wisconsin). So if you’ve spent time in the Southeast, there’s... how to put it... a baseline familiarity about the environment over there.

Global Crisis: War, Climate Change, & Catastrophe in the Seventeenth Century by Geoffrey Parker. This one I’ve got now, and am making my way through.

Kindle samples I’ve read, and I want the whole book of, include:

Flowering Plums and Curio Cabinets, by Sunglim Kim. From the way the book’s presented on Amazon you’d think it was a dry academic analysis of art styles. For all I know what’s past the sample might have some of that, but the start, at least, has tons of bits of info on who was making art, why, where they lived, and what businesses and people could be found where in Hanseong (modern-day Seoul). So it’s potentially a treasure trove of details. Interesting.

A Global History of Ginseng: Imperialism, Modernity and Orientalism, by Heasim Sul. Again, ginseng and history.

Catholics and Anti-Catholicism in Chosŏn Korea by Don Baker and Franklin Rausch. So far an interesting look on the Confucian mindset, and what problems there were with it; some of which led to conversions to Catholicism in Joseon Korea. Only Confucianism was considered the basis of the state, and things got very messy.

The Gunpowder Age: China, Military Innovation, and the Rise of the West in World History, by Tonio Andrade. Covers gunpowder, how it developed, and why there was eventually a split between Europe and China in tech. The author thinks the main problem may have been the Qing Empire had too few enemies, until it suddenly had too many enemies. And thus lost the institutional military skills and know-how needed to keep militaries innovating.

Bringing Whales Ashore: Oceans and the Environment of Early Modern Japan, by Jakobina K. Arch. Where Conrad Totman covered “The Green Archipelago” of Early Modern Japan, and how it kept pressing against its ecological limits, this book wants to cover the “Aquamarine Archipelago” and explore how Japan exploited marine resources through the Tokugawa age on.

The Great East Asian War and the Birth of the Korean Nation by JaHyun Kim Haboush, William Haboush, and Jisoo Kim. Covers the Imjin War, the surprising amount of ordinary people rising in militias, and how that got people of the Joseon Dynasty to start thinking of themselves as a nation instead of just a kingdom.

And there’s at least a half-dozen more samples on Ming, Qing, and Joseon Korea I haven’t gotten to quite yet....

*Stares at list.*

...You know that face you make when you realize you could drop a thousand on Amazon, easy, and barely make a Wishlist dent? Yeah, I’m making that face.

(Especially if I got some of the DVDs I want for story research. Dr. Jin and Live Up To Your Name, to list two. Timetravel isekai! With doctors!)

So! Hope this might come in handy; either for direct research, or for people trying to get a handle on “what do I look for to research history beyond politics?”

#creative writing#writing reference#little ice age#korean history#chinese history#american history#environmental history#isekai

18 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Changes In The Land. Greenhouse Affect #33. Published in the Boston Compass.

#climate change#global warming#environmentalism#boston#massachussetts#history#18th century#environmental history#changes in the land#william cronon

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

"To this day the descendants of those who escaped the Banda massacre use a word for 'history,' fokorndan, that comes from fokor, which means 'mountain' - or rather 'Banda Mountain,' that is to say Gunung Api. This is a way of thinking about the past in which space and time echo each other, and it is by no means particular to the Bandanese. Indeed, this form of thought may well have found its fullest elaboration on the other side of the planet, among the Indigenous peoples of North America, whose spiritual lives and understanding of history were always tied to specific landscapes." Amitav Ghosh: The Nutmeg's Curse: Parables for a Planet in Crisis (2021).

#ecocriticism#ecology#history#ecological restoration#amitav ghosh#nutmeg#enviromental#environmental history

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

0 notes

Text

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

"A tour de force of global history…Bosma has turned the humble sugar crystal into a mighty prism for understanding aspects of global history and the world in which we live."

8 notes

·

View notes

Photo

When, in 1930, Hamilton hosted the swimming events of the first

British Empire Games in its newly constructed indoor Municipal Pool in

the Scott Park area of the city, it showcased a marvelous new facility

that would have been the envy of many larger, more prosperous cities.19

The building of Hamilton's new pool that was used by-but not created

for-the Games had been preceded by at least a decade of public debate

over the provision of swimming facilities for the growing city. Although

city leaders concurred on the positive moral and physical value of swim-

ming for city dwellers, they disagreed over the safest and most appro-

priate locations for beaches on the harbour. Before and during the con-

struction of its municipal pool, Hamilton's locally based City Council

and Parks Board,21 along with its federally based Harbour Commission22

responsible for port development, had invested in creating beaches in

various areas along the bay and along the city's strip of land that sepa-

rated the warm waters of the bay from the colder waters of Lake

Ontario.23 But industrial pollution and the dangers of heavy port traffic

marred beaches near the city's industrial north end, where most of its

working class population lived. Believing that the currents of the bay

would restrict water pollution from city and industrial sewers to only

the southern shore,24 the city acquired waterfront parkland beyond

its corporate limits across the bay on the north shore in 1912, at a place

that had been for decades a popular private park in a neighbouring

township.25

At Wabasso, by contrast, Hamilton's bay waters warmly invited swimming, but they were deteriorating rapidly. Wabasso could well have used a swimming tank too, but many factors worked against it.

As the editor of the Hamilton Spectator put it bluntly in 1926, prob-

lems plagued the place. "Wabasso is possibly more picturesque than

Toronto's playgrounds," he wrote, "...but it can not be said that it offers

better facilities to recreation seekers...the lake shore...has an appeal to

bathers that Wabasso, on the shore of an unclean bay cannot hope to off-

set." Two engineering reports of the day probed the city's sewage and

water treatment problems, showing the sorry state of the bay's waters

where untreated sewage from city and industrial sewers flowed freely.35

As well, the runoff of oil and gas from automobiles drained from streets

and garages ending up floating freely on the bay's surface. Those taking

a plunge at Wabasso invariably had to wash off the coat of oil that stuck

to their skin when they emerged from the water. Even if one did not

mind swimming in dirty waters-and a number of people we have

interviewed have fondly recalled some fun swimming their way through

"turds" and dead fish that floated by other issues doomed Wabasso as

a viable swimming area.37 Many people found the cost of the trip pro-

hibitive to travel from Hamilton across the bay by ferryboat. One edito-

rialist in the local paper put it bluntly, "John Average Workingman, for

whom the park was purchased and developed, hasn't a motor car" to

get there. In vain the City Council negotiated with steam companies to

ensure that steamers would always be running back and forth, provid-

ing good connections between the city and its new park.39 But the cost

of ferry rides often lay outside the financial reach of the city's working

class families, unless they went on one of the ever-popular and fre-

quent company-sponsored picnics held during the summer months.40

Another critic wrote in a letter to the editor, "Why waste time and

money on it? The bathing there is simply impossible; the water has

always been muddy and dirty, and now a superabundance of oil and

sewage makes the water for bathing a most filthy proposition."41 Many

citizens and politicians considered the place to be a "white elephant," a

place whose fate as a city recreational site would hang in limbo for decades to come.42 With public complaints on the rise, and with ever-larger population numbers seeking clean and healthy recreational spaces in the city, local politicians found themselves hard pressed to do something, as observers of the day noted.43 Beginning in the 1920s, swimming pools emerged locally in the public discourse not as a supplement to public beaches, as they often had been presented by advocates. but as an alternative to them. Many held that swimming pools provided a confined and con- trolled environment that could more readily accommodate concerns about safety and ensure appropriate behaviour and decorum than could public beaches, and could do so without endangering the health of swimmers. Those who supported investments in public beaches chal- lenged this latter point. They warned that the confined and nearly stag- nant waters of a swimming pool could provide a better home for bacte- ria than could the bay, whose winds and currents diffused the dangers of bacteria. They pointed to the writings of recreation professionals, who often emphasized the importance of scientific monitoring of water quality. "The modern swimming pool," one such writer noted, "may be a great blessing or a greater curse; a place where wholesome exercise and recreation may be secured, or one of the most effectual mediums for disseminating the germs of disease."45 Opponents of Hamilton's swim- ming pools offered an additional health-related argument that resonated with those engaged in a larger debate over the city's water supply and sewage systems in the 1920s: they contended that the building of new pools would lead city officials to abandon their commitment to main- taining the water quality of the bay. 46 While advocates of pools and public beaches engaged in a prolonged

debate , residents of the city sought safe, clean, and easily accessible places to swim. One alternative came out of the debate over the city's water supply. A 1923 engineering report condemned the old water- works' filtering basins as useless and dangerous to the water supply.47

The basins, located at the southeastern edge of the bay on the lake side

of the beach strip, originally had provided sand filtration for the city's

drinking water drawn in from Lake Ontario, but had long ceased func-

tioning in that way,48 City residents began to swim in them because they

trapped the relatively clean but cold lake water in warm shallow pools.

The city eventually provided amenities for the popular outdoor swim-

ming site, formally calling it the East End (or Lake) Beach, ensuring that

lifeguards, life-saving devices, and toilets (but no dressing rooms) be

made available to swimmers.

Other alternatives to swimming in the bay resulted from the broader public recreation movement that emerged as Hamilton's boundaries stretched and as new suburban housing developments sprang up in the west and east ends, and southwardly atop the Niagara Escarpment (or "Hamilton mountain").50 In the early 1920s, trained specialists began supervising wading pools in newly created playgrounds found in city and school parks.51 This recreational innovation was cropping up in what recreation historian Elsie McFarland terms some of Canada's most socially progressive cities of the day.52 "When the Playgrounds are open," one Hamilton Magistrate is noted to have remarked, "there is a notice- able falling off in juvenile delinquency."53 The city's Parks Board sup- ported the work of Hamilton's Playgrounds Association, a volunteer organization first created by the Local Council of Women in 1909, just a decade after the Board's own creation.54 Initially funded through private subscription made by local benefactors and later through municipal grants, supporters of the city's playgrounds saw them as places to mold the "citizens of tomorrow."55 Local playgrounds began modestly, but soon took off.

When in 1930 the city formally assumed the responsibility for pro- viding playgrounds for its citizens, and formed the members to the Play- ground and Recreation Commission appointed by city council, Syme hailed the move as capping off a year of great achievements.64 A year later, the new Commission took over the management and control of the city's 17 playgrounds, with Syme at its helm. His new office received a line in the city's budget estimates, providing regular funding for salaries, office equipment and supplies, membership fees to national organiza- tions, and other things needed for a vibrant and growing city depart- ment despite the financially hard times of the Great Depression.65 Syme would have been happy, too, that city councillors and local voters also heeded his pleas for a municipal indoor pool to provide citizens with year-round swimming. This, he argued, would take some of the strain felt by the city's YMCA pools at a time when upwards of 4000 kids from the city's 11 playgrounds attended free summer swimming classes.66 Syme's 1928 Annual Report praised the construction of the new Munici- pal Pool, conveniently located at the centre of the city, noting that its pro- visions for free swimming for kids on certain days was a "boon,' filling a real need in the city."67

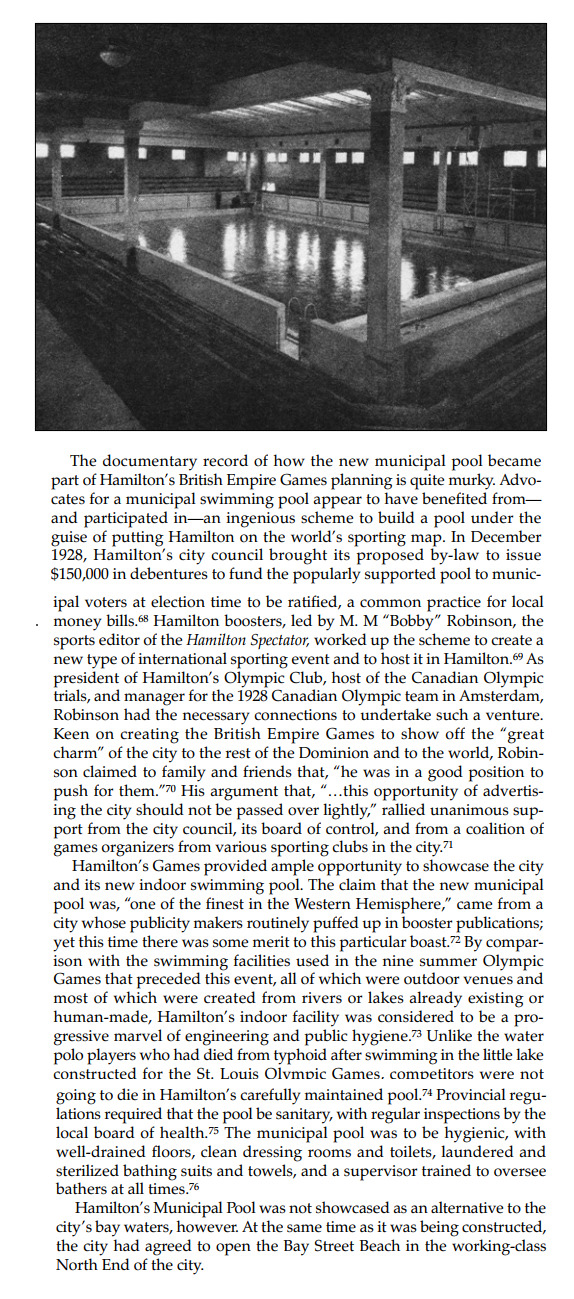

The documentary record of how the new municipal pool became part of Hamilton's British Empire Games planning is quite murky. Advo- cates for a municipal swimming pool appear to have benefited from- and participated in an ingenious scheme to build a pool under the guise of putting Hamilton on the world's sporting map. In December 1928, Hamilton's city council brought its proposed by-law to issue $150,000 in debentures to fund the popularly supported pool to munic-

ipal voters at election time to be ratified, a common practice for local money bills.68 Hamilton boosters, led by M. M "Bobby" Robinson, the sports editor of the Hamilton Spectator, worked up the scheme to create a new type of international sporting event and to host it in Hamilton.69 As president of Hamilton's Olympic Club, host of the Canadian Olympic trials, and manager for the 1928 Canadian Olympic team in Amsterdam, Robinson had the necessary connections to undertake such a venture. Keen on creating the British Empire Games to show off the "great charm" of the city to the rest of the Dominion and to the world, Robin- son claimed to family and friends that, "he was in a good position to push for them."70 His argument that, "...this opportunity of advertis- ing the city should not be passed over lightly," rallied unanimous sup- port from the city council, its board of control, and from a coalition of games organizers from various sporting clubs in the city.71

Hamilton's Games provided ample opportunity to showcase the city and its new indoor swimming pool. The claim that the new municipal pool was, "one of the finest in the Western Hemisphere," came from a city whose publicity makers routinely puffed up in booster publications; yet this time there was some merit to this particular boast.72 By compar- ison with the swimming facilities used in the nine summer Olympic Games that preceded this event, all of which were outdoor venues and most of which were created from rivers or lakes already existing or human-made, Hamilton's indoor facility was considered to be a pro- gressive marvel of engineering and public hygiene. Unlike the water polo players who had died from typhoid after swimming in the little lake constructed for the St. Louis Olympic Games. competitors were not going to die in Hamilton's carefully maintained pool.74 Provincial regu- lations required that the pool be sanitary, with regular inspections by the local board of health.75 The municipal pool was to be hygienic, with well-drained floors, clean dressing rooms and toilets, laundered and

sterilized bathing suits and towels, and a supervisor trained to oversee

bathers at all times.76

Hamilton's Municipal Pool was not showcased as an alternative to the

city's bay waters, however. At the same time as it was being constructed,

the city had agreed to open the Bay Street Beach in the working-class

North End of the city.

While the swimming and water polo events for the Empire Games were held in the new pool, its diving events occurred in the bay, along the revetment wall at Eastwood Park, not far from the new public beach.77 Empire Games organizers thus used both the clean waters of the city's new indoor pool and what they clearly wished to assert were the equally clean waters of the bay. In spite of complaints about oil and gasoline in the water during the 1920s, and although the city invested in a water purification plant in the early 1930s, local officials continued to insist that the bay was safe for swimming. As late as 1939, when Hamilton's Medical Officer of Health investigated the b. coli levels in the water at the Bay Street Beach in the North End, he optimistically concluded that it would be clean for at least 10 more years.7

But he was wrong. Wartime industrial growth accelerated the rate of Hamilton's pollution problem generally and worked to dramatically change perceptions of the bay's water quality. In 1944, the city's Medical Officer of Health closed the popular North End beach and, perhaps unwittingly, helped fuel a debate over the need for clean swimming facilities in Hamilton.79 The debate began with an ingenious scheme to develop postwar public recreation under the guise of a proposed by- law to fund the creation of a memorial to the city's fallen solders.80 Local recreational officials hoped to capitalize on wartime interest in promot- ing physical fitness in the wake of the 1943 National Fitness Act and with the formation of a provisional Wartime Recreational Council to make up for the Great Depression and early war years when city recre- ation had taken, in the words of Syme, "an awful beating." Recre- ational promoters, including the head of Hamilton's Board of Educa- tion, contended that children on the home front were "...becoming one of the serious casualties of the war,"82 so the new Council aimed "...to plan activities to occupy the time and minds of the younger folks during

the summer vacation months."83 The new recreation council was joined by Hamilton's Board of Parks Management, which had aggressively acquired parkland for the city during the interwar years. In 1944, the parks board proposed to help the council by creating more neighbourhood swimming and wading pools, spanning the four corners of the city, and to increase the number of city sports fields through the issue of a half-million dollars in debentures. While this plan raised few eyebrows, it was attached to a much more contentious and expensive idea. The parks board proposed to raise an additional million dollars in order to build a major sports arena as a war memorial. The arena complex was to be developed at Scott Park, near the Municipal Pool, where the stadium had been built and used for the British Empire Games. If successful, such a place could be a financial plum for the parks board, since it received the revenues for places that it controlled. This was not the first ambitious project of its kind; the parks board had championed the creation of the Royal Botanical Gardens at the western end of the harbour in 1941, although the gardens project had not proved to be a moneymaker 85

The proposed by-law for the war memorial scheme became highly

contentious, occupying headlines, editorials and letters to the editor,

and advertisements in the local press. Public debate spilt over into the

airwaves of local radio talk shows,86 Promoters of the by-law sought to

garner support by emphasizing that the new swimming pools would

provide an alternative to swimming in the bay. They portrayed their

opponents as selfish and narrow-minded plutocrats who would con-

demn the inner city children of Hamilton to swimming in the dirty

waters of the bay. "Give Hamilton's Youth the Swimming Pools they

Need!," proclaimed an advertisement put out by the parks board in sup-

port of its venture, "Vote 'FOR' the Parks By-Law!" Calling the parks

board proposal "a refreshing display of sanity," the city's leading news-

paper praised the venture as a sound social investment with something

reaching everyone in the community-"a worthwhile municipal works

program that does not depend on the death of a rich uncle."88

Opponents nevertheless rallied and organized the Hamilton Com- mittee for Continued Sound Administration. They focused on the sports arena, and questioned both the need for such an expensive venture and its appropriateness as a war memorial. They did not question the need for community swimming pools and sports fields, and sought to turn the tables by pointing out that the arena would encourage passive sport spectatorship instead of active physical recreation. Through well-placed advertisements in local papers they asked pointed questions both philo- sophical and practical in nature such as "What is a Fitting War Memor- ial?;" "What Lies Behind the Arena Scheme?," and "Are you being Forced to Vote in order to get Sports and Swimming Facilities in Our Parks?"90 The proposal faced serious opposition of another sort from the mayor, the popular trade unionist Sam Lawrence, and Nora-Frances Henderson, one of the city's most outspoken politicians."1 Both favoured issuing $2 million in debentures for a new city hospital, and contended that the city simply could not bear the financial strain of both projects, no matter how worthwhile.92

Just before the December 1944 vote, the Spectator's city editor wavered in his support for the arena, but warned of the lost opportunity for the development and financing of much-needed community recreation should the by-law be voted down. He forecast the passage of both the war memorial and hospital by-laws." But he was wrong. The parks board strategy of combining community swimming pools and other projects with a commercial entertainment facility did not cut it with Hamilton ratepayers. The debate nevertheless highlighted a growing consensus on swimming pools. Supporters and opponents of the memo- rial arena proposal agreed on the need for community pools, and agreed that they represented a necessary alternative to the city's polluted waters. There were few voices left who believed the waters of the har- bour should or could be kept clean.

By January 1945, just a month after the defeat of the by-law, the wartime recreation council approached the city council to form a civic commission to ensure the development of recreational and leisure opportunities in the city.95 Within a year, the city council passed a new by-law to create the Hamilton Recreation Council, "to assist, encourage, and co-ordinate athletic, sports, recreational and cultural activities...in a local program based on the Ontario provincial plan of fitness and recre- ation." It would involve representatives from the city's various agen- cies, such as the local parks board, playgrounds council, trades and labour congress, local YM and YWCAs, and with representatives from athletic clubs, other social organizations as well as specialists from McMaster University. The Council's activities were subject to the approval of the provincial Ministry of Education, and had to work within the existing frameworks of the Parks Board and the Playgrounds Commission. While it could not "incur any expense or monetary obli- gation" on behalf of the city, it could disburse monies that it received from the city, the province, and other donors.95 It quickly hired a war veteran, A. G. Ley, as the city's new Director of Recreation, giving him office space in city hall. From there, Ley began supervising the train-ng of the city's athletic officials and coaches, helping to determine the

fitness and recreational needs of the city through liaising with neigh-

bourhood recreation councils, and cultivating alliances throughout the

city for times when they needed to lobby for new facilities, like swim-

ming pools.100 Ley moved into action quickly, initially working with

three city neighbourhood councils-one on the Mountain, and the oth-

ers in "two of the better Hamilton residential districts," Westdale and

Normanhurst, 101

Within a year, Hamilton's recreational landscape began to change.

McMaster University hosted the provincial recreation conference to

show off what the city had to offer. Local YMCAs also helped by enlarg-

ing their leadership program offerings to meet local demands for quali-

fied recreational leaders.102 By 1947, the number of neighbourhood coun-

cils quadrupled, rising to 12. Ley noted this feat proudly, proclaiming

that the grassroots model of recreational development worked best and

helped to avoid the problems faced by many other cities, 103 His Council

must have felt some satisfaction when one of the University of Toronto's

social work professors commended Hamilton's "new and different"

approach, noting that "other communities of the province and of Canada

were watching what was going on in Hamilton." The place, he sug-

gested, may provide "a key to the problems of modern life."104 By 1948,

the council got control over the local community centres that had been

established by the provincial and federal governments during the War, 105

also merging with the old Playgrounds Commission to become respon-

sible for all community fitness and recreation programs beyond local

school offerings,106 It did not take long for the city's new recreational bureaucracy to return to an old mantra- that the city needed clean spaces for people to swim owing to the polluted state of the bay. In 1946, the last of the beaches on the harbour, La Salle Park, had been condemned. In the late 1940s, the Recreation Council began to promote the construction of more community swimming pools, forming a special committee on the issue in the early 1950s.107 Without access to well-supervised local swimming pools, observers noted, Hamilton residents were turning to faraway places to swim, like Wasaga Beach along the shore of Georgian Bay, a favourite and relatively affordable summertime haunt for industrial workers and their families. Adopting a well-worn theme, one local

McMaster University professor warned that these were morally dan- gerous places-hangouts for organized gangs from other cities, like "the Toronto Beanery and Junction groups."108 "Persons wanting quiet recre- ation no longer wanted to go to the popular beaches, some of which were vulgar in tone," he noted, and Hamilton, with its neighbourhood councils, was far better off because it provided "healthy recreation for the youth of the district."109

In 1950 the city's Recreational Council began its program of building municipal pools with the Eastwood swimming pool, not far from the location of the old Bay Street Beach. Three years later, the city created three more municipal swimming pools to serve city neighbourhoods, in Inch Park on the Mountain, Coronation Park in Westdale, and Parkdale

in the eastern end of the city. This construction program confirmed that,

in future, swimming would be confined to community parks and would

not take place in the harbour where previous generations of Hamiltoni-

ans had learned to swim. A public health crisis-the loss of swimming as

a healthful recreational activity-had been averted.

Nancy Bouchier and Ken Cruikshank, “Abandoning Nature: Swimming Pools and Clean, Healthy Recreation in Hamilton, Ontario, c. 1930s-1950s,” Canadian Bulletin of Medical History Volume 28:2, 2011: pp. 321, 323-329.

#hamilton#lake ontario#public swimming pools#public beaches#swimming pool#environmental history#pollution#history of pollution#public health#industrial production#history of health care in canada#parks and recreation#history of recreation in canada#youth in history#working class culture#canadian history#academic quote#public spaces#great lakes

1 note

·

View note

Text

I’m on chapter 1 of Sophie Chao’s “In the Shadow of the Palms: More than Human Becomings in West Papua”. In love with how she discusses the way different parts of the environment can mean so many conflicting things. Here, she talks about the Marind’s views on roads.

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Existence Value: Why All of Nature is Important Whether We Can Use it or Not

I spend a lot of time around other nature nerds. We’re a bunch of people from varying backgrounds, places, and generations who all find a deep well of inspiration within the natural world. We’re the sort of people who will happily spend all day outside enjoying seeing wildlife and their habitats without any sort of secondary goal like fishing, foraging, etc. (though some of us engage in those activities, too.) We don’t just fall in love with the places we’ve been, either, but wild locales that we’ve only ever seen in pictures, or heard of from others. We are curators of existence value.

Existence value is exactly what it sounds like–something is considered important and worthwhile simply because it is. It’s at odds with how a lot of folks here in the United States view our “natural resources.” It’s also telling that that is the term most often used to refer collectively to anything that is not a human being, something we have created, or a species we have domesticated, and I have run into many people in my lifetime for whom the only value nature has is what money can be extracted from it. Timber, minerals, water, meat (wild and domestic), mushrooms, and more–for some, these are the sole reasons nature exists, especially if they can be sold for profit. When questioning how deeply imbalanced and harmful our extractive processes have become, I’ve often been told “Well, that’s just the way it is,” as if we shall be forever frozen in the mid-20th century with no opportunity to reimagine industry, technology, or uses thereof.

Moreover, we often assign positive or negative value to a being or place based on whether it directly benefits us or not. Look at how many people want to see deer and elk numbers skyrocket so that they have more to hunt, while advocating for going back to the days when people shot every gray wolf they came across. Barry Holstun Lopez’ classic Of Wolves and Men is just one of several in-depth looks at how deeply ingrained that hatred of the “big bad wolf” is in western mindsets, simply because wolves inconveniently prey on livestock and compete with us for dwindling areas of wild land and the wild game that sustained both species’ ancestors for many millennia. “Good” species are those that give us things; “bad” species are those that refuse to be so complacent.

Even the modern conservation movement often has to appeal to people’s selfishness in order to get us to care about nature. Look at how often we have to argue that a species of rare plant is worth saving because it might have a compound in it we could use for medicine. Think about how we’ve had to explain that we need biodiverse ecosystems, healthy soil, and clean water and air because of the ecosystem services they provide us. We measure the value of trees in dollars based on how they can mitigate air pollution and anthropogenic climate change. It’s frankly depressing how many people won’t understand a problem until we put things in terms of their own self-interest and make it personal. (I see that less as an individual failing, and more our society’s failure to teach empathy and emotional skills in general, but that’s a post for another time.)

Existence value flies in the face of all of those presumptions. It says that a wild animal, or a fungus, or a landscape, is worth preserving simply because it is there, and that is good enough. It argues that the white-tailed deer and the gray wolf are equally valuable regardless of what we think of them or get from them, in part because both are keystone species that have massive positive impacts on the ecosystems they are a part of, and their loss is ecologically devastating.

But even those species whose ecological impact isn’t quite so wide-ranging are still considered to have existence value. And we don’t have to have personally interacted with a place or its natural inhabitants in order to understand their existence value, either. I may never get to visit the Maasai Mara in Kenya, but I wish to see it as protected and cared for as places I visit regularly, like Willapa National Wildlife Refuge. And there are countless other places, whose names I may never know and which may be no larger than a fraction of an acre, that are important in their own right.

I would like more people (in western societies in particular) to be considering this concept of existence value. What happens when we detangle non-human nature from the automatic value judgements we place on it according to our own biases? When we question why we hold certain values, where those values came from, and the motivations of those who handed them to us in the first place, it makes it easier to see the complicated messes beneath the simple, shiny veneer of “Well, that’s just the way it is.”

And then we get to that most dangerous of realizations: it doesn’t have to be this way. It can be different, and better, taking the best of what we’ve accomplished over the years and creating better solutions for the worst of what we’ve done. In the words of Rebecca Buck–aka Tank Girl–“We can be wonderful. We can be magnificent. We can turn this shit around.”

Let’s be clear: rethinking is just the first step. We can’t just uproot ourselves from our current, deeply entrenched technological, social, and environmental situation and instantly create a new way of doing things. Societal change takes time; it takes generations. This is how we got into that situation, and it’s how we’re going to climb out of it and hopefully into something better. Sometimes the best we can do is celebrate small, incremental victories–but that’s better than nothing at all.

Nor can we just ignore the immensely disproportionate impact that has been made on indigenous and other disadvantaged communities by our society (even in some cases where we’ve actually been trying to fix the problems we’ve created.) It does no good to accept nature’s inherent value on its own terms if we do not also extend that acceptance throughout our own society, and to our entire species as a whole.

But I think ruminating on this concept of existence value is a good first step toward breaking ourselves out first and foremost. And then we go from there.

Did you enjoy this post? Consider taking one of my online foraging and natural history classes or hiring me for a guided nature tour, checking out my other articles, or picking up a paperback or ebook I’ve written! You can even buy me a coffee here!

#nature#natural history#ecology#wildlife#animals#environment#environmentalism#conservation#existence value#deep ecology#science#scicomm#environmental philosophy#climate change

556 notes

·

View notes

Text

In February 1959, the threat of inclement weather during the winter months, defined as October through April, led the United States to change the protocol surrounding the arrival of foreign leaders visiting Washington, DC. The Department of State announced that during those months the President would not meet foreign leaders at the airport. During the rest of the year, however, he would.

1 note

·

View note