#episode 81

Text

I love when I’m listening to Welcome to Night Vale and smack in the middle of Cecil talking about whatever random weird-ass thing is going down that week he drops some shit like “the ground isn’t terrifying until it swallows our bodies when they are no longer ours” and then just moves on like he didn’t just change my fucking worldview

#episode 81#I know I’ve said this before#but damn#the cornerstone of modern philosophy#wtnv#welcome to nightvale#welcome to night vale#cecil gershwin palmer#bubbles listens to night vale#400 notes

418 notes

·

View notes

Text

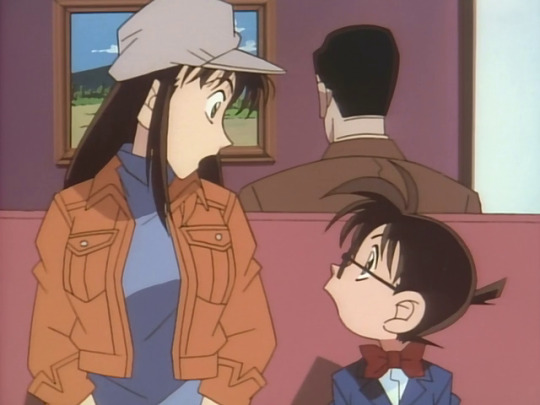

[episode 81 - The Kidnapping of a Popular Artist Case]

#detective conan#episode 81#The Kidnapping of a Popular Artist Case#manga based#edogawa conan#takayama minami#1997#dcmk#1-100#bowtie classic#detco hell original

112 notes

·

View notes

Text

On Heir Awards: Best Bromance

Inspired by the same event, Grace went for Mike Tindall and Princess Anne while Jessica opted for Anne and Prince William

19 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why is it not surprising that Jon was not only bullied as a child but was also deeply annoying when he was a kid.

It just feels so right.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Ty: I’m not the monster you think I am. I’m not trying to torture you.

Michael: Then it must come naturally.

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

Guys I can't...

Hector did NOT just die after a twenty minute graphic description of him being torn apart, before he could even really start loving Jonah for real, right as Jonah becomes full-god-king-thing and needs him most.

And then IMMEDIATELY after I start realizing what happened after the torture of "no more breath returned to [Hector's] blood-filled lungs" and Jonah's vines and crap are LITERALLY embracing Hector's limp body, Nikignik in their interlude is like:

"Are we afraid to lose a loved one, or are we afraid of the moment after?"

Like Nikignik I DON'T CARE, I love you, but I DON'T CARE right now. My gay little couple got ripped apart and I don't have healthy coping mechanisms to grieve properly so I'm just depressed now and there better be some freaking weird End Magic or something that brings Hector back to life because otherwise I don't even know what to do.

And Polly's missing a hand, so things are going downhill :(

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Hang on: are you really tryin' to tell me that no one has bought episode 82 and leaked it???

What am I supposed to do now?!

WAIT???

#jackson’s diary#jacksons diary#webtoon#webcomic#Paola Batalla#Jackson#exer campbell#david miller#Episode 82#Episode 81

43 notes

·

View notes

Text

one piece coming for capitalism/murican bullshit again but this time specifically healthcare.

also the dickhead ruler that made things this way is named wapol, so i guess oda is not only a leftist but also a time traveler and he knew one of the worst examples of capitalism was eventually going to buy the washington post.

oh shit, is oda the doctor. wow like. the "british people's one piece" meme runs deeper than it was intended to.

(for people who dgaf about one piece like, oda is the manga author, not a character)

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

love how anguished charlie is at dugon potentially being gone. after everything he deserves it tbh

#jrwi#episode 81#ambrose reacts#hey besties i am Not holding up well#my voice is hoarse by how loud and how much i screamed#however#i do like hot evil men im not going to lie#niklaus if youre not evil i love you and niklaus if you are evil i love you#both options are good#i like both options#im ignoring how he has all three captains in a deal now#because if i have to think about it more i WILL start crying

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

[Image Description: An edited screenshot of a security camera room in an Ace Attorney game, in which the character Helvetica Orsted has been inserted in the place of Ace Attorney character Larry Butz. Helvetica is a young white man with short, light brown hair with pink ombre tips, and thin rectangle frame-glasses. He wears a beige cardigan and scarf over a white v-neck, and smiles awkwardly. The text-box of the screenshot has been edited to insert Helvetica's name at the top, and reads: "But the thing is. . . I just don't have any interest in men." END ID.]

[Originally posted to Twitter on 05/05/2022]

Evaludate Episode 81: “HIPAA Violation (Helvetica Orsted of Bustafellows, Part 4)”

Summary:

Today on Evaludate: We finally wrap up Helvetica's route, are increasingly shocked by Bustafellows' understanding of medical ethics, get incandescently angry at Helvetica's Side B story, and read some bad poetry.

Content Warnings:

Helvetica's route involves a lot of discussion of drug addiction and human trafficking throughout, please bear this in mind when listening to this episode.

Other content warnings include:

Self-Immolation: (19:58 - 20:17)

Gun Violence: (20:17 - 21:01)

Suicide: (22:56 - 23:13)

Body Horror/Surgical Horror: (34:54 - 35:25)

Medical Abuse: (40:49 - 41:26)

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Transcript Episode 81: The verbs had been being helped by auxiliaries

This is a transcript for Lingthusiasm episode ‘The verbs had been being helped by auxiliaries’. It’s been lightly edited for readability. Listen to the episode here or wherever you get your podcasts. Links to studies mentioned and further reading can be found on the episode show notes page.

[Music]

Lauren: Welcome to Lingthusiasm, a podcast that’s enthusiastic about linguistics! I’m Lauren Gawne.

Gretchen: I’m Gretchen McCulloch. Today, we’re getting enthusiastic about auxiliary verbs. But first, we’re doing a fun experiment. Are there linguistics things in your life that you would like advice about? Whether that’s serious advice or somewhat silly advice, we’re gonna do a special linguistics advice bonus episode for our 7th anniversary coming up in November 2023 with questions from patrons.

Lauren: Ask us your question by following the link in the show notes by September 1st, 2023. We’ll have the episode as our bonus in November 2023. Our most recent bonus episode was a discussion about linguistics and jobs, including a behind-the-scenes on a new academic paper that brings together seven years of interviews with people who have done linguistics and gone on to interesting careers.

Gretchen: You can go to patreon.com/lingthusiasm to get access to these and upcoming bonus episodes and also because our patrons are what lets us make the show. We don’t run advertising. If you like that Lingthusiasm continues to exist, we always appreciate patronage at any level.

[Music]

Lauren: Today, Gretchen, we’re going on an excursion to a farm.

Gretchen: Ooo, what are we gonna see at the farm?

Lauren: We’re gonna see all kinds of animals that we’re gonna use as our example sentences. The first is this horse. The horse is eating grass

Gretchen: Ah, look at the horse! The horse has eaten an apple.

Lauren: Oh, what a nice treat. Both sentences “The horse is eating grass” and “The horse has eaten an apple” are about the verb “eat,” but they’re structured a little differently.

Gretchen: Yeah. They’ve got something in common, which is that they have a main verb “eat” – “is eating grass,” “has eaten an apple” – and also a second helping verb that’s less important when it comes to how we’d draw a nice picture of the scenario but gives us some useful grammatical information.

Lauren: These verbs have their own life as well when they’re not hanging out alongside another verb and helping it. “The horse is eating grass” is the same verb as in “The horse is an animal.” Here “is” is doing the work of painting a picture of what’s happening. The “is” is the whole verb by itself. It doesn’t have any helpers.

Gretchen: The same thing with something like, “The horse has an apple.”

Lauren: Oh, lucky horse.

Gretchen: Lucky horse. We don’t know whether it’s eaten yet, but the “has” there doesn’t have any helpers. It’s not helping. It’s just the only verb. Whereas in “The horse is eating grass,” “The horse has eaten an apple,” you have “eat,” which is your primary verb, star of the show, and then that “is” or “has” that’s helping it out.

Lauren: And those verb-y things that are helping another verb are known as “auxiliary verbs.”

Gretchen: Yeah, “auxiliary” is – the type of terminology, like, “Wow, that’s a long word for such a short verb.”

Lauren: Yes. It’s a very fancy word for when often very short verbs are used to help another verb. It’s because it’s just the very fancy French borrowed word for “help.”

Gretchen: It’s this French word which was borrowed from Latin meaning “helpful” or “aiding.” You do sometimes see an auxiliary, like an “auxiliary armed force” or like a “ladies auxiliary” in a historical military context.

Lauren: True, yes, that is where you may have also encountered the word “auxiliary” outside of linguistics.

Gretchen: I wouldn’t say it’s super common, but there we go. Sometimes, you do see people just refer to them as “helping words” which is also extremely defensible, but the technical, formal word that linguists use is “auxiliary,” which is sometimes shortened nicely to “aux” – just A-U-X.

Lauren: We have auxiliary verbs in English, like the examples we just shared. We can explore how auxiliary verbs work in other languages as well thanks to a very conveniently timed launch of a new database called “Grambank.”

Gretchen: This is very good and coincidental timing. If you’ve listened to previous episodes of Lingthusiasm, you might’ve heard us talk about WALS, which is the World Atlas of Linguistic Structures, which does these cool diagrams of where various linguistic features are found. Grambank is sort of like the new WALS. Let’s talk a little bit about – do you know the history of how these two sites came to be?

Lauren: WALS has been our go-to for almost 20 years. It started out in 2005 as a CD-ROM.

Gretchen: Oh my god, I didn’t realise that it used to be a CD-ROM.

Lauren: Only came online in 2008. The way that WALS works is that an individual researcher would come up with a question, and they would survey as many grammars as they could and then share their results. The way that Grambank works is, instead, they started with almost 200 different features of how the grammar of a language can work, and then they had a massive team – there’s over 100 named authors on the Grambank big, initial publication – and those 100+ authors went through over 2,000 different grammars of different languages looking for each of those 195 different features to put in the database. It’s a very different process.

Gretchen: That’s both more questions than WALS, which has around 90-some questions and also way more languages. Generally, when you see a language map in WALS it’s got maybe about 500 languages, somewhere between 400 and 800 languages, whereas there’s thousands of languages in each of the Grambank databases – not the full, maybe, 7,000 that we think exist, but 2,000-2,500 is certainly a lot closer to having some sense of “What do things like look cross-linguistically?”

Lauren: To pull an example of a grammar completely not at random, one of the coders used my grammar of Lamjung Yolmo. They picked up the grammar, and they opened it up, and they literally went through their list of 195 questions looking for the answers in the grammar and added it to the database.

Gretchen: This is, I think, such a tremendous example of how the work of linguistics involves so many different people because each of the grammars that this database is using as input – and a database like WALS also uses as input – is written by one person or a group of people and can be several hundred pages long and take like 5 or 10 years. Then you have another group of 100+ people spending all this time looking through the grammars and trying to compare them and extract things that make them comparable to each other when grammars are written in different traditions at different times by different people with different interests and try to do something that lets you compare them with respect to each other.

Lauren: One thing that Grambank does really well is that it’s really transparent about the methods it uses. There’s an entire Wiki that goes along with it that explains the process and the methods and what terminology they’re using and why. I think that really helps to make sure that everyone is as much on the same page as possible when it comes to making these decisions.

Gretchen: If you had somebody who’s writing a new grammar, they could look at these 195 questions and say, “I could just provide answers for them in an appendix” or something at the end, so you could just encode them more directly in a future version of Grambank. Are they planning on doing that?

Lauren: This is definitely Version 1.0. There is scope to expand both the number of features they look at the number of grammars that are included in the future, which is also really exciting.

Gretchen: It’s all freely available online, so if you wanna poke around and see what’s in it, that’s a thing that anybody can do.

Lauren: WALS absolutely still has value. I’m sure that we will continue to refer to it when it’s useful, but I’m excited that we’ll also get to use Grambank for future episodes as well.

Gretchen: Yeah. And they ask slightly different sets of questions, so it’s still worth having both sets of resources. But since we have auxiliaries today, and since WALS doesn’t do much with auxiliaries, this is a great time to say, “What does Grambank tell us about auxiliaries in 2000+ languages?”

Lauren: Before we do that, we have to decide what is an auxiliary in any given language. All of those people who wrote those 2,500 references that are included in Grambank, and that means that we have to think about “What are some of the most important features when we’re talking about something as an auxiliary?”

Gretchen: Right. I think a basic working definition of an “auxiliary” is that when you have multiple verbs in the same phrase like “has eaten.” One of them contributes the most to the meaning, and other ones have grammatical function and don’t really have much with their own meaning. In something like, “The horse has an apple,” “has” has a meaning of owning or possession or belonging to, whereas in something like, “The horse has eaten,” it’s not that the horse owns or possesses or belongs to the state of having eaten. It’s an auxiliary in that case where it’s helping out the other verb with grammatical functions.

Lauren: As we’re going through these examples, I think just like we might go for a wander around the hypothetical farm we’re talking about today, we’re also just wandering through these examples and not getting too bogged down on making a complete list. We have that list in the Cambridge Grammar of the English Language. It’s a very big and heavy book.

Gretchen: Speaking of reference works that take multiple people to do, this is also some 2,000+ pages and has 12 co-authors. There’s many people at every level of this process trying to describe what’s going on in a language. This is not an exhaustive tour.

Lauren: In English, we’ve talked about “is” and “has” having auxiliary functions. We also have “do” as in “The horse does eat grass,” which is different to “do” in its main form as “The horse does a dance,” maybe for some dressage.

Gretchen: “The horse does a little dance, does a little jump” – that’s “do” as its canonical, by itself, independent verb form, whereas “The horse does eat grass” is doing a grammatical thing. Similarly, with an example like “The grass was eaten by the horse,” or maybe by a stray goat, the “was” there is doing a grammatical thing and “eaten” is the main verb.

Lauren: “The grass was eaten by the horse” is a really nifty example of how the auxiliary is helping by making the grass the focus and creating this passive structure.

Gretchen: Right. Sometimes, “The horse is eating grass,” or “The horse has eaten grass,” this locates the event of grass-eating in time and the timeline of how this event has happened. Sometimes, it can change how the entities in the sentence relate to each other. There’s lots of different things that auxiliaries can do.

Lauren: Another example of what auxiliaries can do that’s not from my variety of English is “The horse be eating grass” in African American Vernacular English, where instead of the “is” form of the verb, you have the “be” form. That means that it’s being used in a way that means the horse regularly or habitually eats grass.

Gretchen: Which I think is a true thing about horses.

Lauren: I think so. Neither of us are particularly horse experts.

Gretchen: One of the papers that I like to cite about this construction which is called, “Habitual ‘be’,” uses “Cookie Monster be eating cookies” as the example, which is definitely true about cookie monsters. Even if Cookie Monster is not currently eating cookies, this is a thing that is habitually true about Cookie Monster as an entity.

Lauren: That’s a really helpful auxiliary.

Gretchen: It’s interesting how auxiliaries are often drawn from this relatively limited set of words. Here, we’ve seen “be” and “is,” which are part of the same verb, be used in three different ways as slightly different flavours of auxiliary in English because it’s this small set of auxiliaries, and then you can do all these interesting grammatical things with them.

Lauren: There’re all these downstream effects of what happens when you have an auxiliary. Because it’s being used to help in terms of what it’s contributing to the grammar, it means that it’s not coming along with its own meaning as central. Because they no longer bring their own meaning while they’re helping, you get sentences which, if you don’t treat them as an auxiliary, sound a little bit contradictory. So, “I am going to come to the farm,” because “going” is the auxiliary there, you can use it with “come,” which has the opposite meaning if you’re thinking about the meaning of both of these verbs.

Gretchen: Can you say, “I’m coming to go to the farm”?

Lauren: It would be like, “I’m coming to your house, and then we’ll go to the farm together,” so it’s not really an auxiliary.

Gretchen: The one that I really like is – so “have,” which can be an auxiliary or not an auxiliary, is very often pronounced differently in English. It’s spelled the same way, but it’s pronounced differently in English depending on which one it is.

Lauren: Huh.

Gretchen: Let me try this little quiz for you. If I say, “I have two pens” versus “I have to pen up the chickens,” did you notice the difference between how “have” is pronounced there?

Lauren: “I have two pens” and “I have to” – “I hafta,” “I hafta pen up the chicks.” I could make that really short.

Gretchen: One of them is “have” pronounced with the V – “have to” – the other one is “hafta pen” with an F sound, which you could write like “hafta.” It would be sort of weird, I think, to say, “I hafta pens,” to mean “I have two pens.” I don’t think I can do that.

Lauren: “She hasta duck because a chicken is flying over her head” versus “She has two ducks.”

Gretchen: That’s “has” which gets pronounced with a Z when it’s “has two ducks.”

Lauren: When it’s helping, it’s no longer the star of the show. We can smooth down the edges of how we pronounce it.

Gretchen: And make that S or that V more like the T that’s coming after and change the sentence to “She hasta duck.” I think if you say something like, “She has to duck,” it sounds very formal. You can do it, but it sounds very, very formal. [Slowly] “I HAVE to pen up the chickens,” “She HAS to duck” – I just have to say it so slowly in order to not make the “to” into /tə/ and the “have” into /hæf/ and /hæs/.

Lauren: That works for other ones as well. Like, “I’m gonna come to the farm.”

Gretchen: Right. Like, “I’m gonna the farm” – maybe you can say it in some very informal or relaxed varieties.

Lauren: It’s a very informal Australian-sounding pronunciation there.

Gretchen: But like, “I’m gonna milk the cows” or something, like that’s just the one that means future. One that I like is, so, you can say, “I’ve gone away” – you’re reduced that “have,” you know, the auxiliary. It’s shortened from “I have gone away.”

Lauren: “Have” just reduced to /v/ there.

Gretchen: But “I’ve the milk” – do you have that?

Lauren: Now, you sound British in my head.

Gretchen: “I’ve the milk” and “I’ve the eggs.” I think I would have to say, in my Canadian English, “I’ve got the milk” or something like that. I’d have to reinforce the meaning there if I wanna shorten it. I really don’t think I would say, “I’ve to go,” to mean “I have to go.”

Lauren: No. Much harder to shorten a main verb than a helper verb.

Gretchen: I can say, “I gotta go,” “I have to go,” but it’s not quite something I can shorten in that context. Auxiliaries tend to have these sorts of contractions because they’re grammar-y things. They’re very high frequency. Fun fact about high frequency – there’s a very fun study that finds that words that are unexpected in their context or that are less frequent overall in a language tend to be produced over a longer period of time, like slower with longer duration. The example from this that I really like, which is – so there’s a word, “cant,” like a “thieves’ cant” or “the cant of the streets.” You can tell that me saying it with the definition it’s not super common. It’s like an argot. Like, “I heard the cant of the streets going through the night.” This tends to be produced much longer and slower and more precisely than “I can’t” as in “I can’t go,” “I cannot go.”

Lauren: I can’t say “cant” with the same vowel, so it doesn’t work for me, but it does make sense because these auxiliaries are really hard-working helpers. They turn up in sentences so often, and they don’t contribute that meaning. It makes sense that they would be the thing most likely to reduce.

Gretchen: They’re squished down because they’re being grammatical glue between the big meaning-heavy chunks of words. Once we figure out, okay, this counts as an auxiliary, it’s helping the verb in this language, we can then start saying, “What else do auxiliaries do in a particular language that might be of interest when you start zooming in very narrowly on one language?”

Lauren: I know auxiliaries and how we ask questions in English interact in interesting ways.

Gretchen: Right. Let’s look at some examples and questions. We could have “Is the horse eating grass?”, “Has the horse eaten grass?”, “Does the horse eat grass?”

Lauren: In all of these, the auxiliary is at the start – “Is the horse,” “Has the horse,” “Does the horse” – and “eat” is further back.

Gretchen: “Eat” is further back. When those same verbs are used as main verbs rather than auxiliaries, it gets a bit weirder. So, “Eats the horse grass?”

Lauren: Hmm. Hmm. That doesn’t fit with my grammar.

Gretchen: This does exist in the history of English. It’s still something you can say in other Germanic languages, but it’s not something that’s for most present-day English speakers. How do you feel about “Does the horse a dance”?

Lauren: You sound very theatrical, which is usually a way of saying that it is a more archaic form of English.

Gretchen: What about “Has the horse an apple?”

Lauren: Yep, very similar vibes.

Gretchen: I feel like that one sounds a bit British to me also. But “Is the horse an animal?”

Lauren: Yeah, that’s a perfectly normal sentence to my ears. I sometimes have to double check after hearing a bunch of things that I’m questionable about. Be like, “Ah, that is a sentence.”

Gretchen: That’s why I did it in that order just so you could have that happen to you. Yeah! This is a downstream thing that happens with English auxiliaries if you don’t have any auxiliary in the sentence like, “Eats the horse grass?” You have to put one in, “Does the horse eat grass?” or “Can the horse eat grass?” But for some reason, “is” is an exception. I dunno. “Is” is a bit weird. You can check out our copulas episode for more. These are why these aren’t quite used as a diagnostic for auxiliaries, it’s just sort of a thing that happens afterward.

Lauren: Once again, there’s a reason the Cambridge Grammar of the English Language is the size of a relatively healthy cat.

Gretchen: A nice big farm cat.

Lauren: So far, we’ve only had examples of sentences with a single auxiliary, but they are so helpful that they’re willing to stack up and have more than one to help create even more complex meaning in a sentence.

Gretchen: So, if you leave a big barrel of apples on the farm, and there’s a bunch of goats around, by the time you get back into the room, you might see that the apples will have been being eaten by the goats for the whole day.

Lauren: Oh, no. It’s a sad situation but a very exciting use of – was that four? – auxiliaries, “will,” “have,” “been,” “being.”

Gretchen: Yep.

Lauren: And then “eaten.”

Gretchen: Exciting day for the goats. Exciting day for the auxiliaries. Not so exciting for the humans who want to eat the apples. And we still have one main verb, which is “eaten,” because that’s still the action that’s happening, and then all of these other auxiliaries are telling us things about how and when and under what circumstances this event happened.

Lauren: “Do,” “have,” and “be” are doing a lot of heavy lifting in English. We also had a whole episode on modals, which are also like auxiliaries in a lot of ways.

Gretchen: Modals are interesting in English because they don’t act like full verbs, so you can’t just say, “I can the apple,” or “I will the apple,” “I should the apple,” but you can use them in the same auxiliary slot and helping slot as other auxiliaries that are verbs. Sometimes, people talk about auxiliaries as a category that includes verbs that are definitely verb-y, like “be” and “have” and “do,” and other things that are maybe not verb-y, but they’re still doing what seems to be the same helping thing as these helping verbs.

Lauren: Alongside our really common helpers, there are some occasional helpers. “Let” is a really nice example. Something like, “Let’s go.”

Gretchen: “Let’s go.” It’s originally “Let us go,” which sounds very formal to me, and doesn’t quite mean the same thing as “Let my people go,” “Let us go,” it just means, “Shall we go?” or “Let the group of us go” or “Let there be light,” “Let there be peace,” just used as a formal command. “Let” can be an auxiliary because you have these other main verbs like “go” and “be.”

Lauren: That’s a really nice example of how auxiliaries can fork off from their main verb usage and go on their own little adventures. They’re often weird or irregular because they’ll keep this grammatical function that’s separate from their main meaning function.

Gretchen: This grammatical idiosyncrasy of auxiliaries was something that came up a lot when I was learning French. I know you haven’t studied French, but my experience with French was that we spent years and years and years learning this one particular thing about French verbs, which is known as the “passé composé,” which is how to make a certain type of past verb in French, that if you were translating literally, you could translate as something like, “I have eaten,” “I have arrived,” but it’s used to just mean a general past thing. There’s a “have” word there, but it’s used to mean a past thing.

Lauren: It’s nice that it uses “have” as an auxiliary like English does. Big shout out to “have.” I feel like we could have a whole “have” episode.

Gretchen: We really could. In this case, it is “have” most of the time, but sometimes, instead of “have,” it’s “be.”

Lauren: Okay, this is why it took so long to learn.

Gretchen: Yeah. They mean the same thing. There’s just, for a word like “eat,” you use “have,” but for a word like “arrive” or “come” or “descend,” you use “be.” It’s our old friends “have” and “be,” but in this case, it’s like some verbs get “have” and some verbs get “be.” This is actually something that existed historically in English and still exists a little bit in German where you can kind of say in English, “I have come” or “I am arrived.”

Lauren: True. They both work.

Gretchen: In a way that, with other types of verbs, if you say something like, “I am laughed.”

Lauren: Okay, that definitely doesn’t sit well with my intuitions.

Gretchen: No. Or if you say, “I am eaten,” again, well, that means something very different.

Lauren: You’ve got to stay away from those goats. They’re very vicious.

Gretchen: “Help, help, I’m being eaten alive!” Yeah, but you can say, “I am arrived,” in a way that’s a little bit old fashioned, olde-y time-y in English, but doesn’t sound nearly as out there as “I am laughed” for “I have laughed.” But in French, this is obligatory. Some verbs are like, “J'ai mangé,” “I have eaten,” and some verbs are like, “Je suis arrivé,” “I am arrived,” and this is this whole thing that you need to just learn if you’re learning French. It’s also the case in Italian. There’s some stuff in Spanish about which auxiliary verb you need to choose when in these particular grammatical circumstances that is the kind of thing that shows up if you’re learning one of these languages.

Lauren: A good reminder even if two languages use their language’s verb for “have” doesn’t mean they always use them in exactly the same places and in exactly the same ways.

Gretchen: One of my favourite examples of how a word can become grammaticalised and then almost lose it’s original literal meaning comes from Spanish where you have “haber,” which is spelled with an H, and you can see its roots to Latin “habeo,” which is “to have.” This is used for grammatical functions like “El caballo ha comido,” “The horse has eaten,” but it’s no longer really used in most cases for “have” as in “to own” or “to possess.”

Lauren: So, it’s so helpful that it stopped having its own life and now is just helping out.

Gretchen: This is a metaphor, you know, don’t give up on your dreams, “haber”! Now, you have “tener,” which is from Latin and means something like, “to hold” or “to keep.” You can say something like, “El caballo tiene una manzana,” “The horse has an apple,” as like “to have” and “to hold,” which is not the same verb at all that’s used for “has eaten.” But historically, “have” was used for both, and then they were like, “Oh, no, let’s take this other one to mean the more literal meaning of ‘have’.”

Lauren: On the topic of same verb. Latin “habeo” and English “have” – related, not related?

Gretchen: You know, this is the thing that really gets me. They really look like they should be, and they are not.

Lauren: Oh, wow, plot twist.

Gretchen: Plot twist. They are not. You could look this up. We have looked this up. It’s kind of cute. The Wiktionary entry for both “habeo” and for “have” are like, “They’re not related, guys. I’m sorry. We promise. Here’s all the reasons.”

Lauren: Which is why it’s always good to double check these things.

Gretchen: In fact, we don’t think that there was a common Indo-European root for a word meaning “have” because it’s like forked in the descendant languages.

Lauren: Ah, got to save it for the “have” episode.

Gretchen: Oh, yes, sorry. One day we will HAVE an episode about “have.”

Lauren: Acknowledging that auxiliaries can look different in different languages, have slightly different functions, have different downstream effects, let’s return to Grambank and have a look at what they have to say about the spread of auxiliaries across the world’s languages.

Gretchen: Yeah, I wanna find out.

Lauren: The nature of the database means that we can look at the types of questions they have asked, and they’ve asked if auxiliaries are used for a range of different functions across the world’s languages.

Gretchen: One of those functions is, as we’ve seen in English, things like, “is eating,” “has eaten,” things that have to do with when and how and in relation to what an event is taking place.

Lauren: That is the most common use of auxiliary verbs across the world’s languages. It’s way more than 30% of the world’s languages, according to the coding that’s been done, have that kind of auxiliary.

Gretchen: This is formally known as “tense, mood, and aspect.” We’ve done episodes about some of these topics and may do episodes about others of them in the future.

Lauren: The next most common use for auxiliary verbs is to use in negation, which is not quite something we have in English.

Gretchen: In English, you can make a negation by putting “not” after an auxiliary, or depending on how you wanna analyse it, you can add “n’t” to the auxiliary. You can say, “The horse is not eating grass,” which “not” is not acting like a verb there. I can’t say, “The horse not grass.” Or I can say, “The horse isn’t eating grass,” and the “n’t” is attaching to the “is,” which is, again, not a separate auxiliary verb that specifically makes it negation.

Lauren: That’s very different to a language like Irish where the negation changes depending on whether it is happening now or happened in the past. In the present, it is “ní,” and in the past it is “níor.”

Gretchen: Interesting. That’s something that English doesn’t do. What percentage of languages do that auxiliary verb for negation?

Lauren: It’s around 20% of languages in the database have that. The final type of auxiliary use they coded for was, in an English example, “The grass was eaten by the horse” – since the horse didn’t get its grass before, I wanna make sure it has had it now. That passive usage is found in about 10% of languages. The really nice thing about a database like Grambank is that we can click on the map and see that for these passives, there’s this big chain of languages that spread down through the Europe, India, Indo-European area and then down into Southeast Asia. That 10% of languages tend to be focused in that area. There’re large parts of the Pacific and Africa and North and South America where there aren’t as many languages that do this, so we see some kind of common themes among specific languages of certain families or in certain areas that tend to more likely do this. That’s one of the really useful benefits of a big database of features like this.

Gretchen: And one that’s based on a map where you have all of these languages as points on a map.

Lauren: Yeah, totally.

Gretchen: That’s really neat. Seeing languages that are related to each other or just languages that had contact with each other over thousands and thousands of years of history and many people have been bilingual and borrowed things from one language to the next, and you can see these areal groupings of different languages. Auxiliaries are very neat, but clearly, they’re not a thing that all languages necessarily feel the need to use. If a language isn’t using an auxiliary, what are some of the things that they could be doing instead?

Lauren: Grambank tends to code things just on a yes or no basis, so if it doesn’t have it, it’s just coded as a no, but we know there’re some other strategies if you’re not using an auxiliary that you can use to get the same kind of function.

Gretchen: One obvious idea would be to use a suffix or a prefix. If you wanted to say something like, “The grass was eaten,” you could add some sort of ending or some sort of prefix on to “eat” that would make it passive instead of having the “was eaten” part make it passive. This is a strategy that lots of languages do.

Lauren: You might have a prefix for negation instead of some strategy that uses an auxiliary.

Gretchen: You can also use a different type of word. Instead of something being specifically you’re recruiting a helping verb that is verb-y to do your meaning, you could also have a “particle,” which is a glorious linguistic catch-all term for “I dunno. It’s a word doing something.” It’s not obviously a verb. It’s not obviously a noun. It’s just a word that’s there and doesn’t really change its form – like “not,” which I think is a negative particle. Something like “not” is a way of expressing negation rather than changing the end of the word, the beginning of the word, you can have “Let’s just stick in another word.” I don’t think anybody thinks “not” is a verb in English.

Lauren: I don’t know, but different linguists use different criteria for defining what is a verb and what is a particle, so if they have an argument to make for it, then it’d be interesting to hear.

Gretchen: I think in English our standard tests for verb-hood “The horse not the apple” doesn’t seem like it’s acting like a verb there. You could use other words that aren’t necessarily verbs to express negation or passives or any of these complicated tense-y, time-y, timeline-y things.

Lauren: You could say something like, “The horse habitually eats grass.” We have to use “habitually” there or “regularly,” and it makes you realise just how elegant that AAVE construction is using habitual “be” for “The horse be eating grass.”

Gretchen: Or “I eat already” compared to “I have eaten.” The “already” or the “usually” or the “habitually” – adverb-y things – can also sometimes express some of these meanings as well. We’ve given a lot of love to “have” as a very common copula.

Lauren: We have.

Gretchen: We have. But also “be” is a very common copula in a bunch of languages.

Lauren: We are gonna give it some love.

Gretchen: Basque uses “be” as a copula.

Lauren: Ooo, our isolate language of Europe.

Gretchen: Yes. I don’t know enough about the history of Basque to know whether this is related to contact with a bunch of other Indo-European languages in the Spain/France region where Basque is spoken, or whether this is something that is passed down from historical Proto-Basque, but it does use “be” as an auxiliary.

Lauren: Okay. So, still in the European neighbourhood. But we don’t need to stay in that neighbourhood. Palestinian Arabic is another language that has been analysed as using “be” as an auxiliary.

Gretchen: Very nice. We have an example where something like, “She wrote,” is done without an auxiliary, and then something like “She used to write” uses “be” to express that “used to” meaning. “Used to” is another interesting example of an auxiliary in English, actually, now that we’re thinking about it.

Lauren: While we’re collecting them.

Gretchen: Compared to “used two pencils to write.”

Lauren: Hmm, yes.

Gretchen: Also, Kinande, which is a Bantu language, uses “be” as an auxiliary.

Lauren: Excellent.

Gretchen: I have a rather violent example here, which is “We hit (recently, not today),” and “We are hitting,” are both forms of the verb that change based on a prefix. Then “We were (recently, not today) hitting” is a form of the verb that uses “be” to express part of that meaning.

Lauren: So, all using the same “be” verb but in slightly different ways and to achieve different grammatical ends.

Gretchen: Exactly. And showcasing some of the ranges of examples of different types of meanings, whether that’s recent past or “used to” or other types of meanings that can be expressed with an auxiliary just depending on what your language is in to.

Lauren: While they’re not the only verbs that can become auxiliaries, “have” and “be” deserve special shoutouts for being the work horses of auxiliaries across many languages.

Gretchen: We could think of auxiliary verbs as if you are just a person with a shovel, with a rake, trying to plant some seeds, you’re gonna have a bit more difficulty than if you have a plough or you have a horse that can draw it and help you out with your ploughing, so you have the horse helping you out.

Lauren: I think maybe we should think of it as an aux-driven plough instead of an ox-driven plough.

Gretchen: Oh, no, these words sound exactly the same for me. “Ox” as in “oxen,” the animal, and “aux” as in “auxiliary” sound exactly the same for me.

Lauren: This is disappointing where “ox” and “aux” are another thing where I don’t have a merger.

Gretchen: I think actually English might be the only language that has the “ox/aux” merger.

Lauren: Okay.

Gretchen: Because “auxiliary” comes from French, and so French has “auxiliaire” to mean the grammatical thing, but then the animal, like a male cow, is just a “bœuf,” like a “beef.” Whereas German has “Ochs,” as in the cow, but for the grammatical thing it has “Hilfsverb,” which just means “help verb.”

Lauren: Oh, a much more transparent root than English borrowing French auxiliary.

Gretchen: But it does let us make this spectacular joke, which is that you can have an aux-driven verb. There are a few people, including friend of the podcast Kirby Conrod, who sometimes jocularly pluralise “aux,” as in “auxiliary,” as “auxen,” like the cow.

Lauren: Oh, I am definitely gonna start calling them “auxen” from now on. It’s a nice souvenir from our trip to the farm.

[Music]

Gretchen: For more Lingthusiasm and links to all the things mentioned in this episode, go to lingthusiasm.com. You can listen to us on Apple Podcasts, Google Podcasts, Spotify, SoundCloud, YouTube, or wherever else you get your podcasts. You can follow @lingthusiasm on Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, and Tumblr. You can get aesthetic IPA posters, IPA scarves, lots of linguistics t-shirts, and other Lingthusiasm merch at lingthusiasm.com/merch. I can be found as @GretchenAMcC on Twitter, my blog is AllThingsLinguistic.com, and my book about internet language is called Because Internet.

Lauren: I tweet and blog as Superlinguo. Have you listened to all the Lingthusiasm episodes, and you wish there were more? You can get access to an extra Lingthusiasm episode to listen to every month plus our entire archive of bonus episodes to listen to right now at patreon.com/lingthusiasm or follow the links from our website. Have you gotten really into linguistics, and you wish you had more people to talk with about it? Patrons can also get access to our Discord chatroom to talk with other linguistics fans. Plus, all patrons help keep the show ad-free. Recent bonus topics include a liveshow Q&A with Kirby Conrod, our 2022 listener survey responses, and using linguistics in the workplace. If you can’t afford to pledge, that’s okay, too. We also really appreciate it if you can recommend Lingthusiasm to anyone in your life who’s curious about language. And don’t forget to ask us your linguistic advice questions by the 1st of September, 2023.

Gretchen: Lingthusiasm is created and produced by Gretchen McCulloch and Lauren Gawne. Our Senior Producer is Claire Gawne, our Editorial Producer is Sarah Dopierala, and our Production Assistant is Martha Tsutsui-Billins. Our music is “Ancient City” by The Triangles.

Lauren: Stay lingthusiastic!

[Music]

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.

#language#linguistics#lingthusiasm#episode 81#podcasts#transcripts#auxiliary verbs#auxiliaries#verbs#grammar#grambank

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

save him 🙏🙏🙏🙏

[episode 81 - The Kidnapping of a Popular Artist Case]

#detective conan#episode 81#The Kidnapping of a Popular Artist Case#manga based#edogawa conan#takayama minami#yoshida ayumi#tsuburaya mitsuhiko#kojima genta#detective boys#1997#dcmk#this is all faces cone makes in barely first half of that episode...#i cannot even put into words how much i love that case#love love love love 💛💛💛💛#1-100#bowtie classic#detco hell original

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

Join @princesscatherinemiddleton and @duchessofostergotlands as we celebrate our podcast anniversary with our second annual awards ceremony! We look back on the last year and crown the biggest plot twists, the most dramatic glow ups, and the cutest couples.

Episode 81 - “A really middling year” - on Spotify, Apple, Google Podcasts and Amazon!

#on heir#on heir podcast#episode 81#royals#royalty#royal family#british royal family#spanish royal family#dutch royal family#swedish royal family#belgian royal family#jordanian royal family#thai royal family

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Is Jon hiding from the police?

Oh no...

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

this show is so funny because 50% it's their jokes and banter, 50% is the hilarious EDITING

2 notes

·

View notes