#esperanto language

Text

Days of the week (Part I)

Days of the week/Wochentage/Jours de la semaine/Tagoj de la semajno

#english learning#german learning#french learning#esperanto learning#vocabulary#learning language#polyglot#english language#german language#french language#esperanto language#languages#esperanto#jk

15 notes

·

View notes

Text

KIO ESTIS LA PLEJ GRANDA MERDO DE LA TERO? 🌎

youtube

Idioma: Esperanto (contém legenda em esperanto, português, italiano e inglês)

› Acompanhe as redes sociais: Telegram / Twitter / Patreon / Instagram / Ko-fi / Spotify

#esperanto#learn esperanto#learning esperanto#esperantolanguage#esperanto language#learn language#language#Kolekto de Herkso#youtube#idiomas#study language#Studyinesperanto#twitter#ko fi#ko fi page#Youtube#patreon#instagram#telegram#new video#polyglot

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Backrooms 🏠

youtube

Lingvo: Esperanto 💚

Twitter / Patreon

#esperanto#learn esperanto#learning esperanto#esperantolanguage#esperanto language#learn language#language#Kolekto de Herkso#youtube#idiomas#study language#Studyinesperanto#twitter#Youtube#patreon#learning#learn languages#patreon artist#the backrooms#creepycore#Backrooms#scary#creepypasta#creepy aesthetic#horror#polyglot#langblr#language learning#linguistic#vocabulary

16 notes

·

View notes

Text

Esperanto - I-verbo

Mi legas PMEG, mi tre ŝatas kompreni la mekanismojn de lingvo per tia klarigado kiun havas la libro. Mi iom post iom legas, ne vere en ordo. Mi ĵus legis pri I-verboj, kaj, malgraŭ ke estas interesaj la uzadoj, mi iom malfeliĉis pro kelkaj neuzendaĵoj de I-verbo.

Mi vidis ke oni uzas I-verbon post rolvortetoj "krom, anstataŭ, por", kio plaĉis al mi ĉar mi neniam certis pri la ĝusteco, kvankam mi tiel uzis.

Ni ĉiuj kunvenis por priparoli tre gravan aferon

Aŭ eĉ, kio surprizis min, ellaseblas "por":

Ŝi invitis lin trinki kafon (Ŝi invitis min por ke mi trinku kafon)

Malgraŭ ke mi ne komprenas kial, uzante "por", oni ŝajne ne diru "Ŝi invitis min por trinki kafon". Kial ĉi tio estus malĝusta? Ĉu "por" sen "ke" montrus ke kaj ŝi kaj mi trinkos kafon, ne nur mi? Ĉi tio sencas laŭ la frazo kun "kunvenis" supre. Ĉi-kaze, "por + I-verbo" tute uzeblas laŭ mi. Bedaŭrinde nenion diras la libro pri tio.

Kun "anstataŭ" kaj "krom":

La patro, anstataŭ afliktiĝi kiel la patrino, ofte ridadis kaj koleradis

Ne ekzistas alia bono por la homo krom manĝi kaj trinki

Kaj ĉi tie komencas aperi strangaĵoj. Unue estas dirite ke "sen + I-verbo" estas, tradicie, rigardata kiel eraro! La libro eĉ mencias ie kie tio estas vidata kiel eraro, la libro Lingvaj Respondoj, verkita de Zamenhof mem! Kial, Zamenhof, kial vi trovus tion malĝusta?

Malgraŭe, PMEG diras ke tia uzado oftiĝis, kaj tial neniigas miskomprenojn, krom "esti tute logika", kun kio mi tute konsentas.

Sen manĝi kaj trinki oni ne povas vivi

Sed jen venas la plej granda strangaĵo: "post + I-verbo" ne estas kiel ĝusta, almenaŭ tion PMEG lasis subkomptenebla. Ĝi diras ke oni uzas E-finaĵan INT-participon aŭ "post kiam" + plenan subfrazon. Do, oni uzus:

Dirinte tiujn vortojn, li foriris / Post kiam li diris tiujn vortojn, li foriris

Oni uzus ĉi du opciojn anstataŭ "Post diri tiujn vortojn, li foriris". Sed kial ĉi-lasta estas malĝusta? La libro ne klarigas. Laŭ mi tute sencas, des pli pro la simila signifo de I-verbo kun ad-verbo: "Post diri tiujn vortojn" estas kiel "Post diro de tiuj vortoj".

Kaj tia afero ne finiĝas. Ŝajne ankaŭ "pro" + I-verbo estas malĝusta. PMEG ne diras kialo, mi vere ŝatus vidi klarigon pri kial tia kombino estus malĝusta, nelogika. Mi tute logikon ĉi tie:

Li ne povis skribi por ne havi inkon.

Estas tiel konfuze.

"Malgraŭ" + I-verbon oni ne uzas, kaj mi konsentas ĉar vere "malgraŭ" iras antaŭ "kontraŭstara ies volo aŭ fizika baro" kiel diras la signifo de PIV. Tamen "malgraŭ (tio) ke" + I-verbo sencas laŭ mi, kondiĉe ke la I-verbo rolas kiel subjekto, ne kiel perverba priskribo aŭ ago de subjekto. PMEG donas frazon:

Malgraŭ ke li falis, li batalis plu.

Kaj sencas laŭ mi ne uzi "Malgraŭ ke fali", ĉar "fali" nur sonas laŭ mi O-vortece. Kvankam la libro ne diris tion, sencas laŭ mi:

Malgraŭ ke malsaniĝi povas igi nin perdi la atentkapablon, li sukcesis tre bone plenumi sian taskon.

Ankaŭ "dum" + I-verbo estas subkompreneble malĝusta, kaj ĉi tia uzado okazu:

Mi rigardis televidilon dum mi manĝis

Ĉi-kaze "Mi rigardis televidilon dum manĝi" sonas strange, kaj mi ne scias kial. Estas interese ke tio okazas, tial ke "dum manĝado" tute sencas, sed "dum manĝi" sonas kvazaŭ io mankas ĉe "manĝi", kvazaŭ Tarzano parolas ĉi tie; sonas logike, sed primitive. Konsiderante la rilaton I-verbo ≈ AD-verbo, "dum" + I-verbo oni povas diri ke ĝustas, sed, ve, ankoraŭ strangas mi ne scias kial. Eble malkutimeco?

Mi pensas ke, same kiel "malgraŭ" + I-verbo, "dum" + I-verbo nur sencas se la I-verbo ne priskribas ies agon, sed estas subjekto. Do havas logikon la frazo:

Dum paroli estas bone, ankaŭ aŭskulti estas

Post ĉio PMEG diras ke kun la ceteraj prepozicioj oni uzas O-vorton anstataŭ I-verbon, interese nedirante ke I-verbo estas eraro, kio, kune kun tio ke ankaŭ antaŭe ĝi ne direkte diris ke I-verbo tie estis eraro, igas min pensi ke vere ne estas nelogika uzi I-verbon tiel, tia uzado eblas.

Mi mem uzos I-verbon tiel se mi emos; ne ĉar io ne estas ofte uzata, tio estas malĝusta. Tia uzado de I-verbo sencas laŭ mi, kaj mi ŝatis tion, do mi uzos.

7 notes

·

View notes

Text

Here is an inevitably surprising Esperanto video

This is definitely one of my favorites among the Esperanto videos on YouTube. It's a science fiction story, and what make it memorable isn't even the sci-fi stuff itself, but the events of the story.

At first it's completely normal, two characters taking to each other, but then, unexpectedly, out of nowhere, one random thing after another starts happening, you're bombarded with surprises that undoubtedly will make you stare, and even laugh.

The title of the video says it all: Plot Twists. It sums up the whole story.

youtube

This is a translation from a Nur Knabo's post; I just translated because his words described so well what I felt watching the video. It's also a great way to learn Esperanto by the way.

#Esperanto#Esperanto language#conlang#conlanging#Constructed language#Learning languages#Sci-fi#english language#learning english#english as a second language#Youtube#Language learning#langblr

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

Im really curious how people know about Esperanto. Since its a relatively recent language (from the 1880s), its obviously not going to be as widely spoken in the world as other languages (altho apparently it is the most widely spoken constructed language). I assume most people are introduced to it later in some way?

If u know what Esperanto is, feel free 2 reblog this and say how you learned about it in the tags.

#esperanto#original nonsense#i think i saw a tumblr post abt it uears ago but i think the first time i really learned what it was was because#i would listen to the night on the galactic railroad ost on youtube and all the titles are in esperanto.#and i found out later that kenji miyazawa was into esperanto and sometimes wrote in it. so i guess the ost was titled in#that language in reference to that? i think its neat ::-)#thank u all for blowing this post up i love seeing what everyone says. and i accidentally taught some people about esperanto's existence!#hall of fame

3K notes

·

View notes

Text

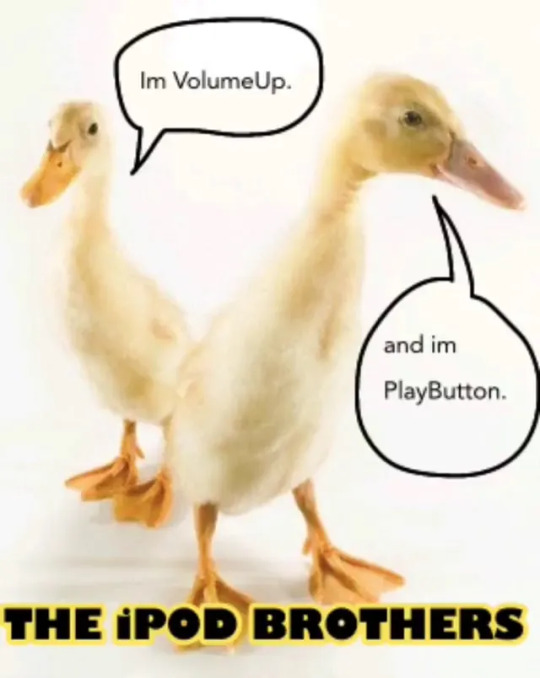

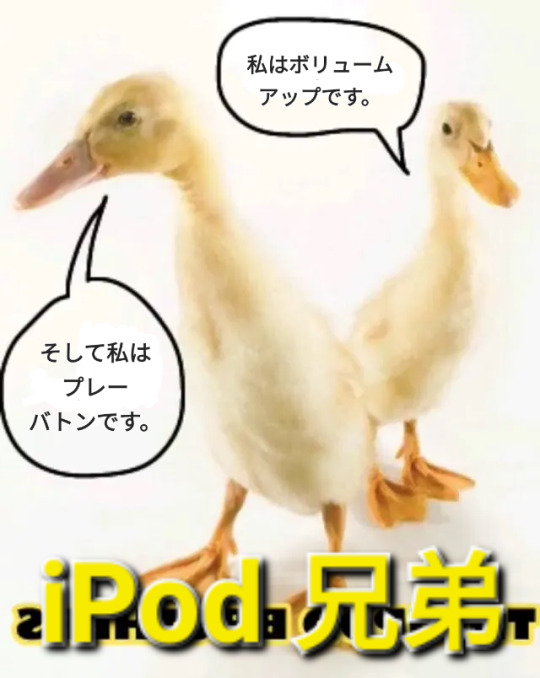

obsessed with the ipod brothers so I made some international versions

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

random thought: what if someone created anti-esperanto? and by that i mean an international language that is designed to be as difficult to learn as possible. if a lot of languages use the same word like for example orange, then it uses something that is completely different and only recognizable to a handful of people. also every single verb must be irregular

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Is there a shared tag for people learning/speaking/enjoying auxiliary languages? I feel like a lot of people who are into esperanto would also be into interlingua/interlingue/interslavic/toki pona or even volapük, and vice versa, but the tags for most of the individual languages are just...absolutely barren. Some unity would do us good for sure

I'd suggest #auxlangblr, to go off the already established term auxlang and connect to the broader #langblr community. I'm open to any other ideas tho :)

Image IDs: the flags of Esperanto, Interlingua and Interslavic, the 3 most widespread constructed auxiliary languages today

#auxlangblr#langblr#esperanto#interlingua#toki pona#interslavic#conlang#auxlang#linguistics#language learning#100

234 notes

·

View notes

Text

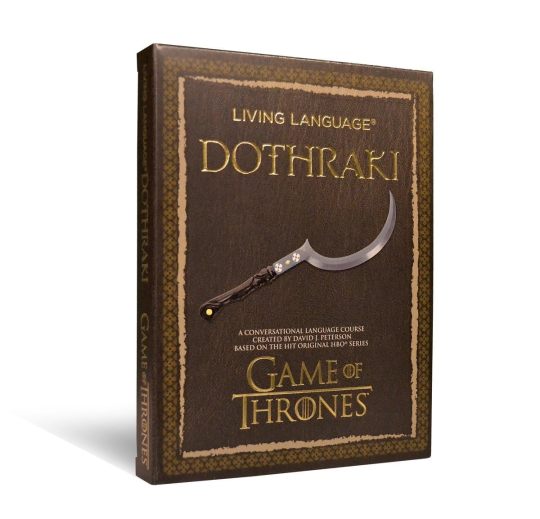

Why I hate conlangs

A conlang (constructed language) is one that was consciously created for some purpose—usually either fiction or global communication—rather than one that developed naturally (Crystal 2008; Wikipedia). Some well-known examples include:

Dothraki, Valyrian (Game of Thrones)

Esperanto

Na’vi (Avatar)

Quenya, Sindarin (Lord of the Rings)

Klingon (Star Trek)

Atlantean (Atlantis: The Lost…

View On WordPress

#American Sign Language#Atlantean#Cantonese#conlangs#Cree#Dothraki#endangered languages#Esperanto#Kikuyu#Klingon#language revitalization#Na&039;vi#Navajo#Nuuchahnulth#Ojibwe#Quechua#Quenya#Sindarin#Star Wars#Valyrian

50 notes

·

View notes

Text

(ID: Spanish Duolingo phrase that reads "Mi gato se llama Señor Pérez. ¡Él está muy feliz y ocupado!" which translates to "My cat is named Mr. Pérez. He's very happy and busy!" The multiple choice translates to "Mr. Pérez: a) is a cat, b) isn't busy, c) is doing badly".)

#duolingo#spanish#please at least provide a translation!#i'm a native spanish speaker so i understood it but if you submit#any other language i may not be able to translate it#(basic esperanto ukrainian german and latin maybe)

63 notes

·

View notes

Text

#language learning#korean language#chinese language#japanese language#esperanto#french language#langblr#polyglot

62 notes

·

View notes

Text

FEK AL ORANĜOJ 🍊

youtube

Idioma: Esperanto (contém legenda em esperanto, português e inglês) 💚

Twitter / Ko-fi ☕

#esperanto#learn esperanto#learning esperanto#esperantolanguage#esperanto language#learn language#language#Kolekto de Herkso#youtube#idiomas#study language#Studyinesperanto#twitter#ko fi#ko fi page#Youtube

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

Akiru la filmojn dublitajn en Esperanto ĉi tie!

Christopher R. Mihm › Instagram

#Filmojn dublitajn#Esperanto#languages#learn languages#language#esperanto language#esperantolanguage#learning#polyglot#Christopher R. Mihm#Mihmiverse

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Demanda pleonasmo en Esperanto

Ĉi tion mi pensis antaŭ kelkaj jaroj jam, kaj eĉ prikomentis en la tiama Tvitero. Je tiu momento, krome, estis kiam mi unuafoje vidis la ĝenan malemon de Esperantistoj al io nova en la lingvo, eĉ se neformale, kiel miakaze.

Nur por certeco ke ni ne miskomprenos: pleonasmo estas frazfiguro kie oni uzas nenecesa(j)n vorto(j)n por specifa celata emfazo, esprimo. Ekzemplo: "Mi vidis per miaj propraj okuloj." La vortoj "per miaj propraj okuloj" estas nenecesaj, tial ke "vidi" jam diras ke per okuloj oni vidis, sed tamen ili funkcias por emfazo.

Mi proponis similan aferon al Esperanto por fari demandojn, per la partikulo "ĉu".

La diferenco inter la anglismo "eĉ"

"Eĉ" estu uzita nur kiam oni volas emfazi la fakton, la realecon de okazaĵo; ekzemple: "Ŝi batis lian kapon tiel forte, ke li eĉ svenis." Skeme ni povas diri ke frazoj kun "eĉ" havas strukturon similan al ĉi tiu: iu ago/okazaĵo estas tia influa, ke tio ĉi okazas.

Tial frazo kiel "Kion vi eĉ volas?" ne sencas, estas laŭ mi klara angla influo el la frazo "What do you even want?" aŭ simila, ĉar "even" tradukeblas al "eĉ", sed ĝi ĉi tie ne havas la sencon de "eĉ", kiu ĉiam emfazas vorton, neniam tutan frazon, aŭ demandon, kiel "even" ĉi-kaze. Kondiĉe ke ĉi tiu specifa nuanco estas aldonita al "eĉ", kaj vi sciu ke Esperantistoj ne multe ŝatas tiaĵon, tia uzado ne sencas. "Kion vi eĉ volas?" nur sencas, se oni faras ĉi tiun demandon post priskribo kiel: "La knabineto iris al ĉiu evento kun la verkisto, spektis ĉiun paroladon lian, aĉetis lian novan libron kaj eĉ volis foton kun li." Do: "Kion ŝi eĉ volis?"

Esperanto, do, ne havas partikulon por ĉi tia emfazo. Mi do elpensis uzi "ĉu" por ĉi tio: "Kion ĉu vi volas?" Kaj ĝi uzeblas kun ajna demandvorto.

Ĉi tio estas nur neformalaĵo al la lingvo, ne ke mi volas aldoni ĉi tion al la Esperanta gramatiko. Ja videblas ke ĉiutaga lingvaĵo diferenciĝas de la norma, oni kreas vortojn kaj esprimojn por interparoli, kaj ĉi tio estas unu el ili. Praktike, tamen, mi scias ke ĉi tia "ĉu" ne venkos, oni nek akceptos nek komprenos ĝin, do, nu, estas nur afero mia.

Per norma Esperanto mem

Aliflanke, mi trovis pli bonan vojon, kiu jam ekzistas en Esperanto kaj evitas malemulojn, kaj kiun mi uzos.

Montriĝas ke la difino de "kiel" ĉe PIV havas la interesan variaĵon "kiele", kun E-finaĵo. PIV diras ke ĝi estas emfazo de "kiel" kiel adverbo, en frazo tia: "Kiel bela estas la ĉielo!" > "Kiele bela estas la ĉielo!" Sed, nu, kial ĝi ne povas esti uzata por la aliaj signifoj de "kiel"? Kompreneble ĝi povas. Aldone, kiale la E-finaĵo ne povus esti tiel uzata ĉe aliaj demandvortoj? Ĉi tio eblas tute.

Fakte, laŭvorte ankaŭ kelkaj minutoj, koincide dum mi ankoraŭ faris ĉi afiŝon, oni demandis ĉe la Diskorda servilo Esperanto pri difino ĉe Tuja Vortaro kie uzatas E-finaĵo ĉe "tiel": "Okazis tiele" Estis interese ekscii ke jam estas almenaŭ iomete da tia uzado en la lingvo, sed neniel surprize ke Esperanto al ni permesas tian grandan fleksiĝon. Ja eblas la E-finaĵo kiel emfazo ĉe ĉiu tabelvorto.

2 notes

·

View notes

Link

Leizer Ludwik Zamenhof (1859–1917) created Esperanto to be a global second language. A Lithuanian Jew, Zamenhof grew up under Russian occupation and amid the tensions between Jews, Catholic Poles, Orthodox Russians, and Protestant Germans. He identified miscommunication as the main cause of this trouble.

First, Zamenhof tried to create a standardized Yiddish to unify Jews across the Russian Empire. In the end, he abandoned it in favor of a universal language, whose name means “the hoping one.”

Underlying this project was Zamenhof’s interna ideo, the belief that the language did not represent an end in itself but a step toward world peace and understanding.

He published his Fundamento de Esperanto in 1905, striving to maximize simplicity, efficiency, and elegance. The grammar has just sixteen rules, the spelling is phonetic, the nouns are genderless, and the verbs are regular and uninflected. He tested and expanded it by translating the Bible, Shakespeare, Moliere, and Goethe.

Esperanto shares some features with Yiddish and Ladino, Jewish lingua francas that had once helped erase borders. Some studies identify a Yiddish influence, though Zamenhof never mentioned one.

Esperanto’s vocabulary poses a problem for twenty-first century internationalists, because it comes solely from European languages. Aficionados have invented other constructed languages (conlangs), like Lingwa de Planeta, that include non-European words, but Esperanto continues to dominate the field.

Other conlangs like Ido, Interlingue, and Interlingua have remained tiny but resilient, but only Esperanto has truly stood the test of time. Today, just under one million people know a little of the language, and ten million have studied it. It has a stable but de-territorialized speech community.

The League of Nations supported the idea of an auxiliary language, and in 1954 UNESCO gave the Universala Esperanto-Asocio (UEA) “consultative status.” Various Protestant and Catholic denominations have tolerated the use of Esperanto as a liturgical language. The founder of the Baha’i Faith supported the idea of a conlang; some of its followers favor Esperanto while others prefer Interlingua.

Critics call Esperanto artificial and acultural. But the distinction between natural and artificial is hard to maintain in the case of languages. Pidgins are also “artificial,” arising at an identifiable time and place, but many evolve into creoles, indisputably natural languages. Many states standardize and legislate their official languages. Language reformers invented much of the phonology, morphology, grammar, and vocabulary of modern Chinese. And writers often shape and reshape their mother tongues, as a glance at Shakespeare’s neologisms — foul-mouthed, swagger, bedazzle — demonstrates. If words adjudged possible can become actual words, possible languages can become actual languages.

Further, Esperanto does not lack culture. Some two thousand denaskuloj, or native speakers, have been raised in it, thus creolizing it. More than one hundred periodicals appear in it, and there are thirty thousand Esperanto books and several full-length feature films.

104 notes

·

View notes