#ezz-thetics

Text

Hans Koch / Paul Lovens — Nephlokokkygia 1992 (ezz-thetics)

Nephlokokkygia 1992 by Hans Koch & Paul Lovens

Rummaging one day through his trove of concert recordings, Paul Lovens came across an unexpected find of tapes from his tour through Bulgaria in 1992 with Swiss reeds player Hans Koch. With some editing and studio polishing, the aural artifacts of this tour now see the light of day as the ezz-thetics CD Nephlokokkygia 1992.

Having previously shared the stage at various times in larger projects, Lovens and Koch were not strangers to each other's playing. But this Bulgarian tour served as their initial foray in a duo formation. Since first taking over the drum chair from Jackie Liebezeit in the late 1960s as part of Alexander Schlippenbach's long-running Globe Unity Orchestra, Lovens has been a permanent fixture and inexhaustibly creative voice on the European free improvisation scene. Though perhaps primarily best known through his work with the Swiss Koch Schütz Studer trio, Hans Koch has performed with many of the leading exponents in the world of free improvisation, including Cecil Taylor, Evan Parker, Fred Frith and Barry Guy.

Still, despite these outwardly contextual similarities Lovens and Koch come from two very different ends of the musical spectrum, with Lovens mainly being a self-taught drummer and Koch having studied classical repertoire at conservatories in Biel and Zürich. Precisely these differences make the Lovens-Koch duo an interesting proposition, if not on paper a baffling one. For at first glance, despite both players' love and dedication to free improvisation, it would seem the middle ground might exceed their grasp. Nephlokokkygia 1992 proves this assumption very wrong.

The CD also provides a glimpse into the world of free improvisation on the cusp of momentous changes in the use of electronics, found sounds and reductionist improvisational strategies, as embodied in the form of self-proclaimed movements like the New London Silence or echtzeitmusik in Berlin. The style of very tactile, expressionistic and dynamically explosive playing found on Nephlokokkygia 1992 would in the course of the 1990s soon be relegated to more of an historical afterthought, as musicians increasingly turned to laminal, if not at times downright static and barely audible, approaches to free improvisation.

But not so on Nephlokokkygia 1992, where Lovens and Koch joyously test the limits of their instruments and approach to form. The four tracks on the CD, each named after the city they were recorded in, follow the chronology of their Bulgarian tour. This allows the listener to hear not only the development of the music within each piece on the CD, but as the overall tour progressed, each concert building on the one before, the initial strategies from the first date at times shattering or coalescing with each successive stop on the tour.

One could argue that Nephlokokkygia 1992 offers a portrait of Lovens and Koch at the proverbial height of their powers, both at the time in their early 40s and each with decades of touring and recording already under their belts. Lovens variously sounds like the percussion section from a Noh theater piece gone slightly awry, someone washing up pots and pans in the kitchen or a fourth-dimensional version of Baby Dodds. One could almost designate Lovens' approach as pointillistic, often concentrating for extended lengths of time on one element of his yard-sale drum set. This could mean bowing a set of crotales, lightly tapping his ride cymbal, pressure-pitching the skin of his snare or interjecting massive bass drum bombs. The jury is still out on Lovens' use of the musical saw, which can sometimes come across as circus sideshow distraction or downright provocation, depending on the musical context or one's disposition.

But where Lovens always shines is in his sense of dynamics and the ability to interject form in the most unlikely of places. He seems to be playing with Koch yet at the same time not bothering to listen all that closely, as if this would defuse the mystery and tension of two contiguous streams of sound happening in the same physical space but in reality belonging to two very different aesthetic and psychological realms. We could sometimes imagine Lovens not caring at all about what he plays, until the realization sneaks up and grabs us from behind, shaking us violently as the music coalesces into yet another direction, another shape and form. It would be no exaggeration to call Lovens' playing something like a force of nature, not just in its strength but in the innately organic flow of his musical gesture.

This all places collaborators in the predicament of how to react — or not react — to Lovens' mercurial presence. To complicate matters, the duo setting leaves virtually nowhere to hide, to step back and take a breather while other members in a larger group constellation could pick up the thread. And in this sense, one would have to grant Koch something like a Medal of Valor for having the tenacity, and humor, to meet Lovens' fleeting nature with something approaching an unblinking eye. To these ends, Koch straddles the field between abstractly sonic playing — implementing extensive overblowing, multiphonics and guttural vocalizations — to an aesthetic more keenly reflecting his conservatory training, speeding through an array of tonal runs, snippets of melody or phrasing that at times evokes jazz or classical music. Koch especially excels in the more extreme nether reaches of his instruments, plumbing the depths of his bass clarinet, or sounding like an oscillator spinning wildly out of control as he tweaks the highest register of his soprano saxophone.

Precisely Lovens' and Koch's two disparate approaches make Nephlokokkygia 1992 a stunning listen. This is music that somehow exists outside conventional notions of musicality, yet hones extraordinarily close to the very essence of what music is all about: the desire to catch a fleeting glimpse of what freedom might mean, if only for the span of an evening's worth of music.

Jason Kahn

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

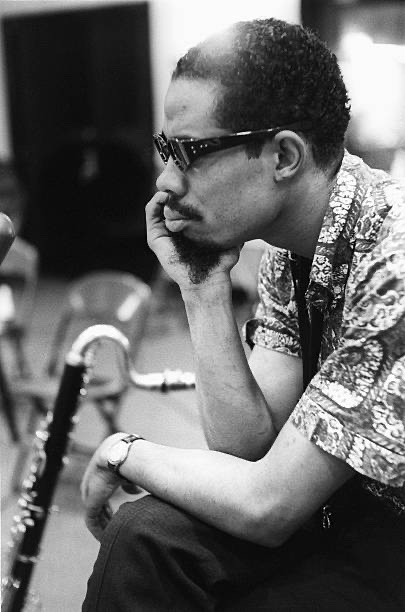

multi-instrumentalist Eric Dolphy during the recording sessions for George Russell's Ezz-thetics album at Riverside Studios, c.1961

photo: Steve Schapiro

via ryujazz on Tumblr

12 notes

·

View notes

Audio

Listen/purchase: Ghosts (Munich Studio Production) by albertayler-ezz-thetics

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

Eric Dolphy, recording sessions for George Russell's Ezz-thetics album at Riverside Studios, ca. 1961

39 notes

·

View notes

Text

youtube

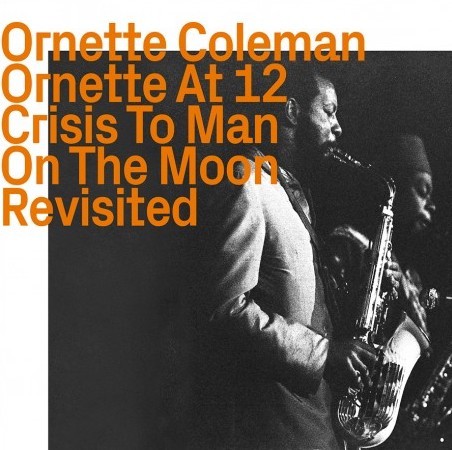

"Ornette At 12, Crisis To Man On The Moon Revisited" (2023, ezz-thetics) reissuses these records on 1 CD. From Crisis, here's my father's tune "Song For Che". w/ Ornette, Charlie, Don Cherry, Dewey Redman, Denardo Coleman.

1 note

·

View note

Text

8/27 おはようございます。 Sarah Vaughan / at Mister Kellys mg20326 等更新完了しました。

Sarah Vaughan / at Mister Kellys mg20326Julie London / Around Midnight Lst7164Sarah Vaughan / After Hours At The London House Mg20383Dizzy Gillespie / World Statesman v8174Jackie McLean / Lights Out prst7757Lee Konitz Miles Davis Teddy Charles Jimmy Raney / Ezz-thetic njlp8295Oscar Peterson / Plays The Cole Porter Songbook mgvs6083Oliver Nelson / Live From Los Angeles as9153Art Blakey / Like…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Co w jazzie piszczy [sezon 1 odcinek 15]

premierowa emisja 2 sierpnia 2023 – 18:00

Graliśmy:

Pierrick Pedron / Gonzalo Rubalcaba “Ezz-Thetic” z albumu “Pedron Rubalcaba” – Gazebo

Freddie Bryant “Columbus, Quiet – Haiku #1” z albumu “Upper West Side Love Story”

Phil Haynes, Drew Gress, David Liebman “To Swing or Not(II)” z albumu “CODA(s): No Fast Food III” – Corner Store Jazz

Marc Ribot’s Ceramic Dog „That’s Entertainment” z albumu…

View On WordPress

#April Records#Ceramic Dog#Chaikin Records#Christian Ramond#Christopher Dell#Co w jazzie piszczy#Corner Store Jazz#Criss Cross Jazz#Damon Locks#Dave Liebman#David Hazeltine#Drew Gress#Emil de Waal#Freddie Bryant#Gazebo#Gondwana Records#Gonzalo Rubalcaba#Gustaf Ljunggren#International Anthem#Ken Vandermark#Klaus Kugel#Knockwurst Records#Lilamors#Madeleine & Salomon#Marc Ribot#MAtt Otto#Nate Wooley#Phi-Psonics#Phil Haynes#Pierrick Pedron

0 notes

Text

今日の昼下がりジャズ「Max Roach +4」'56

1曲目の「Ezz-Thetic」から物凄いインパクト。2曲目でドラムをフィーチャーして、3曲目の超高速「Just One Of…」で再び息をつかせぬスピード感。そしてB面の有名曲2曲を含むバラエティー豊富な内容で最後まで飽きずに楽しめます。

絶好調のロリンズとドーハムをフロントに配した、クリフォードとパウエルが亡くなった直後のグレートなクインテット。ジャケも何だか喪に服してるみたいだけど、ローチはめちゃ笑顔(笑)

何だかんだで、僕のドーハム・コレクションが増えてますが、これってハマってるって事かな?この演奏はめちゃ良いと思います。

円盤組合でこの名盤のUS盤が480円!音は良いしノイズも少ない。良い買い物が出来ました。

1 note

·

View note

Text

Favorites Revisited album review @ All About Jazz

Favorites Revisited album review @ All About Jazz

By Chris May

May 19, 2022

Sign in to view read count

” data-original-title=”” title=””>John Coltrane‘s classic quartet, Favorites Revisited delivers one and a quarter hours of landmark live recordings in state-of-the-art 21st century audio. Professionally recorded, and therefore sounding pretty good even on original release, the material now benefits from remastering by the ezz-thetics label’s…

View On WordPress

0 notes

Text

Edu Haubensak & Thomas Korber, 'Works For Guitar & Percussion: Buck-Wolfarth' CD (ezz-thetics)

Tuesday, December 28, 2021, 6:51pm (full listen)

As much as I like this disc, and will definitely bring it out again after its imminent filing, I have to admit to having it play mostly in the background for this listen. However, this allowed the album to also shine in this particular light, too, with its stark, gently insistent minimalist pieces suiting my other tasks very nicely indeed. This is a type of album that exictes me and makes me want to make music; I also have a friend who I think will be similarly charmed by it, so I know it won't be too long before I hear it again (and in the meantime will keep eyes peeled for more work by all parties involved).

#Edu Haubensak Thomas Korber#minimalism#contemporary composition#ezz-thetics#christian buck#christian wolfarth

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Under the Radar: Jim Marks' Year-end List for 2023

Samuel Leipold, Jürg Bucher, Lucca Lo Bianco

The stream of great new music is constant and impossible to keep up with. Inevitably, some of it goes largely unnoticed. My year-end list consists of releases that I really enjoyed but didn’t get around to writing about and haven’t seen reviewed elsewhere in English. They are presented in no particular order.

Samuel Leipold, Jürg Bucher, Lucca Lo Bianco — Ostro (Ezz-thetics)

This trio of clarinet, double bass, and guitar delivers atmospheric free jazz. Experimental without being confrontational (included is a choice Jimmy Giuffre cover), Ostro offers a rarely heard sound palette and consistently interesting arrangements.

Luis Ribeiro — A Invenção da Ficção (Porta Jazz)

The Porta Jazz label out of Portugal released fewer records than usual this year, perhaps a lagging effect of Covid. One standout is the debut by guitarist and composer Ribeiro, who leads a sextet with tenor and baritone saxophones in the front line. Love the eerie vocalization on the opening track. Space age and swinging.

Adrián Royo Trío — Pangea (Errabal Jazz)

youtube

This Spanish release initially caught my eye in the La Habitacion de Jazz blog because of the involvement of double bassist Manel Fortià. Strong original melodies and tight interplay make for a standout piano trio recording in a great year for piano trios.

Javier Burin — Escenarios (Los Años Luz Discos)

Another excellent but low-profile piano trio release this year. The assuredness and inventiveness of Argentinian Burin’s playing are the more remarkable given that he is only in his early twenties; check out especially the unlikely cover of “Tenor Madness.”

Marcus Eads — Pride of Ostego (self-released)

This Minnesotan has been putting out gentle Takoma-style guitar music for more than a decade. Strongly rooted in the rural midwestern landscape, his playing and homespun compositions call to mind back porches, canoe trips, and sitting by the fireside.

Scott Tuma — Nobody’s Music (Haha)

I was thrilled to stumble across this unheralded release recently by the Souled American alumnus and one of the architects of slowcore. Apparently first appearing last year on cassette, Nobody’s Music, coming six years after No Greener Grass, delivers more ambling and spindly acoustic guitar lines that seem to drip out of the instrument with the occasional accompaniment of what sounds like harmonica or accordion. Enchanting as always.

Mohamed Masmoudi — Villes Éternelles (Centre des Musiciens du Monde)

Canadian oud master Masmoudi creates a compelling blend of Arabic music and jazz in a percussion-less quartet also featuring clarinet, piano, and double bass. With top-notch musicianship and catchy tunes, the group shows how good world music fusion can sound.

Jorge Abadias — Camins (Underpool)

The Underpool label documents the lively Barcelona jazz scene. Its 2023 releases include this quartet date led by guitarist Abadias. His original post-bop (in the broad sense) compositions tend toward slower tempos, and fine soloing abounds.

Jakob Dreyer — Songs, Hymns, and Ballads Vol. 2 (self-released)

Another solid post-bop quartet recording featuring original compositions. Three U.S. musicians fill out German double bassist Dreyer’s quartet, and this second volume nicely complements Vol. 1 released last year.

Various Artists — You Better Mind: Southeastern Songs to Stop Cop City (self-released)

This project, spearheaded by the Magic Tuber String Band (who also released the outstanding Tarantism in 2023), brings together a broad swath of musicians, including Joseph Allred, Shane Parish, Sally Anne Morgan, Nathan Bowles, the Tubers themselves, and some I was unfamiliar with. The music tends toward the rustic; much of it is excellent, and the cause is as noble as they come.

Jim Marks

#dusted magazine#yearend 2023#jim marks#samuel leipold#jürg bucher#lucca lo bianco#luis ribeiro#adrián royo trío#javier burin#marcus eads#scott tuma#mohamed masmoudi#jorge abadias#jakob dreyer#magic tuber string band

6 notes

·

View notes

Photo

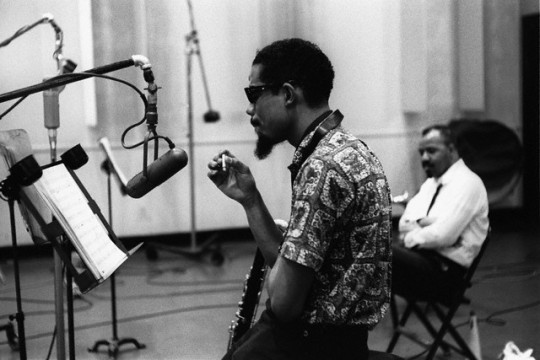

Eric Dolphy during the recording sessions for George Russell's Ezz-thetics album at Riverside Studios. David Baker, trombonist, sits in the background. Steve Schapiro, 1961

Source: Getty Images

107 notes

·

View notes

Video

Miles Davis - Ezz-thetic

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Lee Konitz, jazz alto saxophonist who was a founding influence on the ‘cool school’ of the 1950s died aged 92

The music critic Gary Giddins once likened the alto saxophone playing of Lee Konitz, who has died aged 92 from complications of Covid-19, to the sound of someone “thinking out loud”. In the hothouse of an impulsive, spontaneous music, Konitz sounded like a jazz player from a different habitat entirely – a man immersed in contemplation more than impassioned tumult, a patient explorer of fine-tuned nuances.

Konitz played with a delicate intelligence and meticulous attention to detail, his phrasing impassively steady in its dynamics but bewitching in line. Yet he relished the risks of improvising. He loved long, curling melodies that kept their ultimate destinations hidden, he had a pure tone that eschewed dramatic embellishments, and he seemed to have all the time in the world. “Lee really likes playing with no music there at all,” the trumpeter Kenny Wheeler once told me. “He’ll say ‘You start this tune’ and you’ll say ‘What tune?’ and he’ll say ‘I don’t care, just start.’”

Born in Chicago, the youngest of three sons of immigrant parents – an Austrian father, who ran a laundry business, and a Russian mother, who encouraged his musical interests – Konitz became a founding influence on the 1950s “cool school”, which was, in part, an attempt to get out of the way of the almost unavoidable dominance of Charlie Parker on post-1940s jazz. For all his technical brilliance, Parker was a raw, earthy and impassioned player, and rarely far from the blues. As a child, Konitz studied the clarinet with a member of Chicago Symphony Orchestra and he had a classical player’s silvery purity of tone; he avoided both heart-on-sleeve vibrato and the staccato accents characterising bebop.

However, Konitz and Parker had a mutual admiration for the saxophone sound of Lester Young – much accelerated but still audible in Parker’s phrasing, tonally recognisable in Konitz’s poignant, stately and rather melancholy sound. Konitz switched from clarinet to saxophone in 1942, initially adopting the tenor instrument. He began playing professionally, and encountered Lennie Tristano, the blind, autocratic, musically visionary Chicago pianist who was probably the biggest single influence on the cool movement. Tristano valued an almost mathematically pristine melodic inventiveness over emotional colouration in music, and was obsessive in its pursuit. “He felt and communicated that music was a serious matter,” Konitz said. “It wasn’t a game, or a means of making a living, it was a life force.”

Tristano came close to anticipating free improvisation more than a decade before the notion took wider hold, and his impatience with the dictatorship of popular songs and their inexorable chord patterns – then the underpinnings of virtually all jazz – affected all his disciples. Konitz declared much later that a self-contained, standalone improvised solo with its own inner logic, rather than a string of variations on chords, was always his objective. His pursuit of this dream put pressures on his career that many musicians with less exacting standards were able to avoid.

Konitz switched from tenor to alto saxophone in the 1940s. He worked with the clarinettist Jerry Wald, and by 20 he was in Claude Thornhill’s dance band. This subtle outfit was widely admired for its slow-moving, atmospheric “clouds of sound” arrangements, and its use of what jazz hardliners sometimes dismissed as “front-parlour instruments” – bassoons, French horns, bass clarinets and flutes.

Regular Thornhill arrangers included the saxophonist Gerry Mulligan and the classically influenced pianist Gil Evans. Miles Davis was also drawn into an experimental composing circle that regularly met in Evans’s New York apartment. The result was a series of Thornhill-like pieces arranged for a nine-piece band showcasing Davis’s fragile-sounding trumpet. The 1949 and 1950 sessions became immortalised as the Birth of the Cool recordings, though they then made little impact. Davis was the figurehead, but the playing was ensemble-based and Konitz’s plaintive, breathy alto saxophone already stood out, particularly on such drifting tone-poems as Moon Dreams.

Konitz maintained the relationship with Tristano until 1951, before going his own way with the trombonist Tyree Glenn, and then with the popular, advanced-swing Stan Kenton orchestra. Konitz’s delicacy inevitably toughened in the tumult of the Kenton sound, and the orchestra’s power jolted him out of Tristano’s favourite long, pale, minimally inflected lines into more fragmented, bop-like figures. But the saxophonist really preferred small-group improvisation. He began to lead his own bands, frequently with the pianist Ronnie Ball and the bassist Peter Ind, and sometimes with the guitarist Billy Bauer and the brilliant West Coast tenor saxophonist Warne Marsh.

In 1961 Konitz recorded the album Motion with John Coltrane’s drummer Elvin Jones and the bassist Sonny Dallas. Jones’s intensity and Konitz’s whimsical delicacy unexpectedly turned out to be a perfect match. Konitz also struck up the first of what were to be many significant European connections, touring the continent with the Austrian saxophonist Hans Koller and the Swedish saxophone player Lars Gullin. He drifted between playing and teaching when his studious avoidance of the musically obvious reduced his bookings, but he resumed working with Tristano and Marsh for some live dates in 1964, and played with the equally dedicated and serious Jim Hall, the thinking fan’s guitarist.

Konitz loved the duo format’s opportunities for intimate improvised conversation. Indifferent to commercial niceties, he delivered five versions of Alone Together on the 1967 album The Lee Konitz Duets, first exploring it unaccompanied and then with a variety of other halves including the vibraphonist Karl Berger. The saxophonist Joe Henderson and the trombonist Marshall Brown also found much common ground with Konitz in this setting. Konitz developed the idea on 1970s recordings with the pianist-bassist Red Mitchell and the pianist Hal Galper – fascinating exercises in linear melodic suppleness with the gently unobtrusive Galper; more harmonically taxing and wider-ranging sax adventures against Mitchell’s unbending chord frameworks.

Despite his interest in new departures, Konitz never entirely embraced the experimental avant garde, or rejected the lyrical possibilities of conventional tonality. But he became interested in the music of the pianist Paul Bley and his wife, the composer Carla Bley, and in 1987 participated in surprising experiments in totally free and non jazz-based improvisation with the British guitarist Derek Bailey and others.

Konitz also taught extensively – face to face, and via posted tapes to students around the world. Teaching was his refuge, and he often apparently preferred it to performance. In 1974 Konitz, working with Mitchell and the alto saxophonist Jackie McLean in Denmark, recorded a brilliant standards album, Jazz à Juan, with the pianist Martial Solal, the bassist Niels-Henning Orsted Pedersen and the drummer Daniel Humair. That year, too, Konitz released the captivating, unaccompanied Lone-Lee with its spare and logical improvising, and a fitfully free-funky exploration with Davis’s bass-drums team of Dave Holland and Jack DeJohnette.

In the 1980s, Konitz worked extensively with Solal and the pianist Michel Petrucciani, and made a fascinating album with a Swedish octet led by the pianist Lars Sjösten – in memory of the compositions of Gullin, some of which had originally been dedicated to Konitz from their collaborations in the 1950s. With the pianist Harold Danko, Konitz produced music of remarkable freshness, including the open, unpremeditated Wild As Springtime recorded in Glasgow in 1984. Sometimes performing as a duo, sometimes within quartets and quintets, the Konitz/Danko pairing was to become one of the most productive of Konitz’s musical relationships.

Still tirelessly revealing how much spontaneous material could be spun from the same tunes – Alone Together and George Russell’s Ezz-thetic were among his favourites – by the end of the 1980s Konitz was also broadening his options through the use of the soprano saxophone. His importance to European fans was confirmed in 1992 when he received the Danish Jazzpar prize. He spent the 1990s moving between conventional jazz, open-improvisation and cross-genre explorations, sometimes with chamber groups, string ensembles and full classical orchestras.

On a fine session in 1992 with players including the pianist Kenny Barron, Konitz confirmed how gracefully shapely yet completely free from romantic excess he could be on standards material. He worked with such comparably improv-devoted perfectionists as Paul Motian, Steve Swallow, John Abercrombie, Marc Johnson and Joey Baron late in that decade. In 2000 he showed how open to wider persuasions he remained when he joined the Axis String Quartet on a repertoire devoted to 20th-century French composers including Erik Satie, Claude Debussy and Maurice Ravel.

In 2002 Konitz headlined the London jazz festival, opening the show by inviting the audience to collectively hum a single note while he blew five absorbing minutes of typically airy, variously reluctant and impetuous alto sax variations over it. The early 21st century also heralded a prolific sequence of recordings – including Live at Birdland with the pianist Brad Mehldau and some structurally intricate genre-bending with the saxophonist Ohad Talmor’s unorthodox lineups.

Pianist Richie Beirach’s duet with Konitz - untypically playing the soprano instrument - on the impromptu Universal Lament was a casually exquisite highlight of Knowing Lee (2011), an album that also compellingly contrasted Konitz’s gauzy sax sound with Dave Liebman’s grittier one.

Konitz was co-founder of the leaderless quartet Enfants Terribles (with Baron, the guitarist Bill Frisell and the bassist Gary Peacock) and recorded the standards-morphing album Live at the Blue Note (2012), which included a mischievous fusion of Cole Porter’s What Is This Thing Called Love? and Subconscious-Lee, the famous Konitz original he had composed for the same chord sequence. First Meeting: Live in London Vol 1 (2013) captured Konitz’s improv set in 2010 with the pianist Dan Tepfer, bassist Michael Janisch and drummer Jeff Williams, and at 2015’s Cheltenham Jazz Festival, the old master both played and softly sang in company with an empathic younger pioneer, the trumpeter Dave Douglas. Late that year, the 88-year-old scattered some characteristically pungent sax propositions and a few quirky scat vocals into the path of Barron’s trio on Frescalalto (2017).

Cologne’s accomplished WDR Big Band also invited Konitz (a resident in the German city for some years) to record new arrangements of his and Tristano’s music, and in 2018 his performance with the Brandenburg State Orchestra of Prisma, Gunter Buhles’s concerto for alto saxophone and full orchestra, was released. In senior years as in youth, Konitz kept on confirming Wheeler’s view that he was never happier than when he didn’t know what was coming next.

Konitz was married twice; he is survived by two sons, Josh and Paul, and three daughters, Rebecca, Stephanie and Karen, three grandchildren and a great-grandchild.

• Lee Konitz, musician, born 13 October 1927; died 15 April 2020

Daily inspiration. Discover more photos at http://justforbooks.tumblr.com

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

8/27 おはようございます。Cal Tjader / the Shining Sea cj159 等更新完了しました。

Sarah Vaughan / at Mister Kellys mg20326

Julie London / Around Midnight Lst7164

Sarah Vaughan / After Hours At The London House Mg20383

Dizzy Gillespie / World Statesman v8174

Jackie McLean / Lights Out prst7757

Lee Konitz Miles Davis Teddy Charles Jimmy Raney / Ezz-thetic njlp8295

Oscar Peterson / Plays The Cole Porter Songbook mgvs6083

Oliver Nelson / Live From Los Angeles as9153

Art Blakey / Like Someone in Love Bst84245

Sonny Criss / Crisscraft Mr5068

Freddie Hubbard / Breaking Point bst84172

Freddie Hubbard / Straight Life cti6007

Larry Coryell / Fairyland M51-5000

Sonny Stitt / Mellow MR5067

Cal Tjader / the Shining Sea cj159

John McLaughlin / Devotion sdgl65075

~bamboo music~

530-0028 大阪市北区万歳町3-41 シロノビル104号

06-6363-2700

0 notes