#femicide in my country has made me write this

Text

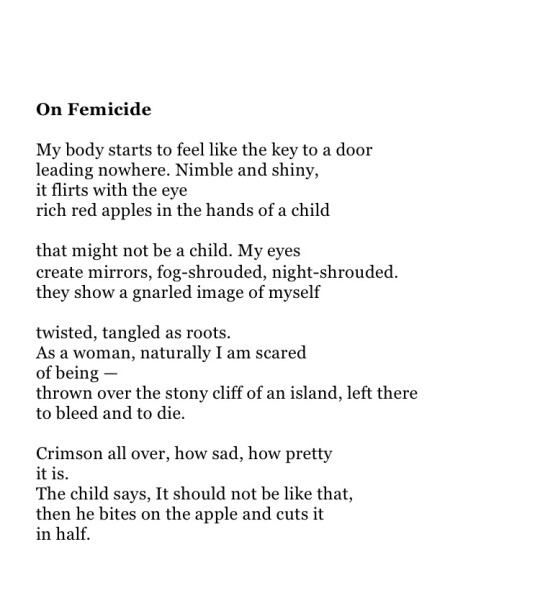

Demi Ev / On Femicide

#My poetry#femicide in my country has made me write this#It is getting out of hand#It’s not a normal thing to happen#to murder a woman because of a ‘bad moment’#just no

241 notes

·

View notes

Text

Fandom bitches are such frail little sluts who seek NOTHING but escapism, instant gratification and uncritical validation. You all can't handle criticism, you can't handle something requiring effort, practice, time, blood, tears and sweat to be good, you can't handle being told NO, or to – literally or metaphorically – go outside.

And don't you bitches try to excuse that last one with bUt EsCaPiSiM iS mY cOpInG mEcHaNiSm!!!!! BeCaUsE [blank].

Bitch, I'm a physically disabled, autistic, psychiatrized, broke, non-white lesbian living in a 3rd world country that's been going through A LOT of shit since last October, a country with tons of femicides and lesbicides, and I carry mountains upon mountains of personal trauma. I KNOW about escapism as a coping mechanism but 1) YOU CAN'T MAKE A COPING MECHANISM YOUR WHOLE LIFE, 2) the concept of coping mechanisms points to the fact that not all of those are good for you.

If anything, the fact you all get to NOT DIE while ignoring what's going on around you tells me you're much more privileged than you think, because I would probably have gotten my head kicked into the sidewalk if I'd kept walking around in public with my double Venus necklace, which I stopped doing after learning about all those lesbicides. I can't escape what's going on here because I won't know what fucked up shit carabineros are doing this time and I could literally lose an eye like so many other Chileans have. I can't ignore if there's any news of monetary state aid BECAUSE I'M BROKE.

What's more, since, while not perfect, I'm not an entirely selfish self-centered little cunt, I do choose to force myself to escape less than I need to for myself, because I live within a community that I care about. So not only are you guys more privileged than you think, you're also selfish individualists and prove yet again that fandom culture as it exists NOW is nothing but a sick expression of capitalist individualism and consumerism so typical of American culture (yes, even if you're not American yourself).

You can't go around demanding to be coddled by strangers and have people act like your fanfics are God's gift to humankind or on the same level as genius traditionally published authors from the past or present.

You can't act like you, utilizing the creative efforts of SOMEONE ELSE (their universe, mythology, symbols, characters, plot, themes and so on) are being a creative genius yourself. You're writing derivative work from someone else's already well formulated efforts. It's like buying a pre-made pizza from the supermarket, putting it into the microwave, and calling yourself a chef for doing that.

This isn't even to say that fanfiction is Bad or inherently stupid. It's to ground you back into the reality that, while fun and a decent creative warm up, it's not high art or some shit. And that's ok! It's a cute hobby. I don't fucking get why so many of you have to make that hobby your whole identity or sense of self-worth to the point that if someone (correctly) says it's not high literature you have a fucking meltdown.

If you're mad because fanfic is all you do with your life so it not being the most vital form of creative work makes you feel like you're doing nothing of value with your life, then maybe work on the root problem of that. The solution to that isn't the general public agreeing that your Avengers coffeeshop AU is at the same level of Dante's Inferno or Paradise Lost.

Or maybe, just maybe, stop being such whiny spoiled coddled arrogant brats. If you want your craft to be considered a serious one, then you have to be able to tolerate criticism, it has to be held to the SAME standards that the craft of traditionally published authors are held to. Learn to tolerate being told no, being told you're not God's gift on Earth, being told your work has flaws. If you can't take that, then accept that writing is just a hobby for you. THAT'S NOT EVEN A BAD THING, FOR FUCK'S SAKE.

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

“All goodness is in jeopardy”: Dead Girls at the End of the Decade

“As another year comes to pass, bringing another decade to pass, we find ourselves awash in the bodies of dead girls and women, fictional and very much real.”

This essay was originally set to be published in December 2019 on Much Ado About Cinema, to coincide with the premiere of Jennifer Reeder’s Knives and Skin.

There is a film that premieres today, the last month of the decade, called Knives and Skin. Directed by Jennifer Reeder, the film depicts the surreal transformation a community undergoes when one of its own, a teenage girl named Carolyn Harper, goes missing and later shows up dead. Knives and Skin may in fact be this decade’s last work of art to employ a narrative device come lately to be known as the “dead girl trope.” This term refers to the use in story of this conceit—a beautiful, young, presumably innocent, usually white girl has gone missing or wound up dead (almost always murdered), plunging the incredulous family/community/town surrounding her into chaos and calling a charismatic detective to chase after answers.

Much lately has been made of the dead girl trope—researching its origins, examining its variations, interrogating its largely uncontested whiteness and cisness. Of course stories of dead and missing women have been around as long as women have died and gone missing, but since the early ‘90s the trope has clogged up the culture, and even moreso in the past decade. Every day we are inundated with stories of women battered, disappeared, manipulated, and killed. We cannot afford to be flip or numb, to treat these stories as just that—fiction, as anything separate from the culture they have a mutually parasitic relationship with. The most important question people have begun to ask of the dead girl trope is whether it has any capacity to attack the misogyny it depicts and uproot the racism and transphobia which support it. Or does recycling the trope again and again, even by creators with the most altruistic intentions, do anything other than entrench the idea that violence is the logical conclusion to the question of a woman?

As the final installment in a decade long saga of women on the verge, how does Knives and Skin measure up? To answer this question we have to do two things. We have to understand the real world stakes, and we have to go back to where this bad dream began.

“When this kind of fire starts, it is very hard to put out.

The tender boughs of innocence burn first,

and the wind rises, and then all goodness is in jeopardy.”

-Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me

As another year comes to pass, bringing another decade to pass, we find ourselves awash in the bodies of dead girls and women, fictional and very much real.

In the world, women are abducted, disappeared, if returned at all returned in bruised condition, mass graves are discovered, long buried reports of abuse are painfully unearthed, and women are killed. In Nigeria, in 2014, 276 schoolgirls abducted from the town of Chibok by Boko Haram and driven hundreds of miles into ungoverned territory. Five years on, 112 are still missing. Bereft parents have died waiting for their daughters to be returned. “Even in a hundred years,” one mother told a reporter from Al Jazeera this year, “we will keep believing that our daughters will return home.”

In Canada, after years of fierce organizing from within indigenous communities, the government finally launched an inquiry into the murder and disappearance of thousands of indigenous women stretching back decades. The National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, as it’s called, attribute it to "state actions and inactions rooted in colonialism and colonial ideologies.” Indigenous leaders name it: genocide.

In our own country, thousands of immigrant women are detained, many having fled their homes due to domestic violence, state-sponsored sexual violence and femicide only to wind up in dehumanizing internment, their children confiscated from them like personal effects. A rising number of mass shooters explicitly name the hatred of women as a call to action, their patterns of domestic abuse (86% of the 22 mass shooters analyzed in a recent Mother Jones report had demonstrable records) shored up too late. Trans women and gender non-conforming afab (assigned female at birth) people face an epidemic of transphobic, misogynistic, often racist violence from intimate partners and total strangers alike. Violence in the street is entrenched by the indifference of the state—of the 22 trans women murdered this year to date, 18 cases remain unsolved.

In the culture, the flood of women’s bodies rises from our ankles to our thighs. Scanning best of the decade lists—it’s easy to see if you’re looking, and even if you’re not, it’s hard to ignore—dead and missing girls are everywhere. Though the carnage is not distributed evenly across formats—there is for example a remarkable lack of dead girl stories in film when compared with the superabundance in television and podcasts—the sheer volume is staggering.

Podcasting emerged as the most exciting new storytelling medium this decade, transforming from local radio curio to culture-spanning phenomenon attracting big tech money and A-list celebrity buy-in. The medium, built on the backs of stories of dead and missing women, has proven unable to go on without them. The show that kickstarted the podcast revolution was Serial, a solemn journalistic inquiry into the unsolved murder of a teenage girl. Serial set off a true crime boom as much as it set a template for much of the medium. Though few shows have applied the same rigor to their dead, damaged, or missing subjects, none have needed to in order to become wildly popular. Simply put, there is no dead woman that eludes the reach of the podcaster, and without dead women, there would be no podcasts as we know them.

Finally, my god, television. It’s not that a number of the best shows of the decade centered on the story of a dead or missing girl; there were in fact so many they constituted a thematic center for the entire medium this decade—The Killing, The Fall, Broadchurch, Pretty Little Liars, How to Get Away With Murder, Making A Murderer, Top of the Lake, True Detective, The Night Of, and The Jinx, to name some of the heavy hitters.

One more show waded into the morass this decade, and most notably—it was the reason for all this mess in the first place.

David Lynch came back to television after 25 years with Twin Peaks: The Return, a third season to his legendary 1990 television series. By all accounts, those original eight episodes launched the beautiful dead girl craze we’re still in the vicious throes of. The entire Twin Peaks universe—Lynch and Mark Frost’s surprise smash first season, the meandering second season in which ABC rescinded creative control from Lynch because he refused to identify the dead girl in question’s killer, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me, Lynch’s controversial 1992 feature prequel which features Laura Palmer, dead girl, as an alive protagonist rather than a silent mystery, the new season, and all the apocryphal literary spinoffs—centers on the beautiful, murdered, porcelain-white body of homecoming queen Laura Palmer, washed up on a riverbank in the pilot episode.

Every piece of writing on the dead girl trope addresses Lynch, if not exclusively, then in a fulsome manner. Alice Bolin, who published a comprehensive book of essays on the trope last year called Dead Girls: Surviving an American Obsession, first engaged with the subject in a 2014 essay on Twin Peaks for the Los Angeles Review of Books. And indeed, nearly every review of Knives and Skin I encountered while researching for this essay references Twin Peaks as an obvious ancestor to Reeder’s film.

Why? The aesthetic comparisons are evident—moody score, weird acting, woodsy small town setting, beautiful missing, and then dead, girl. But the comparison is broader than that. It’s almost compulsory, unavoidable. The impact Twin Peaks had on culture is impossible to understate. But the depth to which the twin images of Laura Palmer’s ghostly, smiling, peroxide and permed homecoming photo and her dead, drowned, blue-faced and plastic-wrapped crime scene photo, which the show flashes to in alternation, have seeped into our core imagining of what women fundamentally are in life and in death has absolutely not been reckoned with.

This Knives and Skin grasps. The film’s Laura Palmer, called Carolyn Harper (Raven Whitley), behaves much in the same way. In her first and only alive scene, she and a boy drive up to the shore of a lake at night. Without knowing anything about the film the first time I watched it, I tensed, anticipating exactly what ended up happening. Carolyn and the boy, Andy (Ty Olwin), walk from the car to the lakeside, silhouetted in the glare of the headlights. Before kissing, the two bicker about Carolyn’s glasses, whether they should stay on or be taken off. Andy says “keep ‘em on, I don’t care.” Carolyn responds: “I do care. I actually don’t want to see what’s about to happen.” The next time anyone in the film sees Carolyn, she’s dead.

If Knives and Skin does anything perfectly it’s this. The Laura Palmers of fiction and the Laura Palmers in fact, all around the world, have fused, like the twin images in Twin Peaks—alive: radiant, dead: serene, and in both cases speechless, compliant. It recalls Maggie Nelson’s question after seeing Hitchcock’s Vertigo: “whether women were somehow always already dead, or, conversely, had somehow not yet begun to exist.”

An avatar of young womanhood as always arcing toward extermination has emerged with a juggernaut’s relentlessness out of the scrum of the past three decades of dead girl TV. The characters in Knives and Skin live in this world. Carolyn Harper knows what happens to Carolyn Harpers. She doesn’t want to see “what’s about to happen” because she’s powerless to prevent it. The tagline of the film, “Have you seen Carolyn Harper?” lands as a joke by the end of the film. Carolyn Harpers are all we ever see.

Knives and Skin doesn’t so much rage with righteous injustice over the unfair and unthinkable death of one young girl as it does turn the palpable, ten-ton heavy despair of unfair and unthinkable death as the condition of young girls back on the viewer. “You guys doing okay,” Carolyn’s mother asks three of her daughters classmates who’ve brought her condolence casseroles. Carolyn’s body has just been discovered. An ice cream cake made for her birthday melts into a pale pool of sludge on the table before her. “Yes,” they say, emotionless. “You lying?” They nod again, “yes.”

Reeder has taken us back to the world of Twin Peaks in a time where dead girls are taken for granted, taken as givens. They still, however, even in this most melancholy meditation, destroy communities and upend lives. I’ve said that Knives and Skin doesn’t rage with injustice over the death of Carolyn Harper. But should it?

The reference point that floated into my head while watching Knives and Skin the first time, that I couldn’t shake the second time was not Twin Peaks, but its much maligned and misunderstood prequel, Fire Walk With Me. Lynch made Fire Walk With Me after Bob Iger and ABC tried to stage manage the surprise success of season 1 by forcing him to reveal Laura’s killer. “‘Who killed Laura Palmer?’ was a question that we did not ever really want to answer,” Lynch later told TV Guide. Season 2, largely without Lynch, was as a result baffling, anticlimactic and sensational in all the wrong places. The show was cancelled less than two years after debuting. Fire Walk With Me was a vengeance quest, Lynch’s intent to bring closure and justice to the story of a Pandora he had never intended to let out of the box.

Fire Walk With Me is brutal. Its examination of trauma is surgical, uncompromising, and to the bone. For the majority of the film the camera is glued to Laura, who walks, talks, dances, laughs, gobbles like a turkey, screams, cries, and eventually dies. As a spectator you are shoved in close proximity to Laura. Unlike the silent, pliant Laura Palmer of Twin Peaks, Sheryl Lee’s Laura in Fire Walk With Me is fully alive, every fantasy concocted about her by the characters in season 1 as well as the fans in the audience is in sharp, contested relief. She feels everything done to her immediately, unbearably, and so do you.

Many critics hated Fire Walk With Me, and it was a commercial flop. The film was booed at Cannes. In the New York Times, Vincent Canby wrote: “Everything about David Lynch’s Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me is a deception. It’s not the worst movie ever made; it just seems to be.” In a discussion on the dead girl trope for The New Republic, Sarah Marshall offered a remark that speaks directly to the film’s icy reception: “a dead woman is utterly incapable of offering up even the most cursory contradiction to the narratives that entomb her as readily as any casket.” Fire Walk With Me was one huge, bleeding contradiction.

The original bad dream, the dead girl’s nightmare we still haven’t woken up from was actually unpacked all those years ago, just months after it all began. Laura’s killer was her father, Leland. Her father had been sexually abusing her since she was a child, her mother knew, and within hours of Laura finally perceiving this fact in its full reality, he killed her. All of the weirdness, the quirkiness, and horror of Twin Peaks, along with the enduring, eroticized, and profitable trope it popularized emanates from this very personal, achingly common story of childhood sexual abuse. Is it any wonder people hated it? Or why the Laura Palmer of the original series is the figure we’ve chosen to preserve, pressed flat into the pages of culture forever?

“All goodness is in jeopardy,” the Log Lady warns Laura before entering the roadhouse where her life will begin to tailspin before its eventual crash. This is the essence and the power of the dead girl story. Though we have erected a world that is impossible for women to navigate unscathed, we continue to vest them with the symbolic responsibility of innocence. As if Laura’s singular life was the first domino in a chain that led to the unraveling of the entire world. But wasn’t it?

Many have pointed out the racial and gender-specific freighting of the dead girl trope. Could Laura Palmer have been Latinx? How would the movie change if Carolyn Harper had been African-American, or trans? The answer on every level, symbolic and real, is drastically. What these depictions unconsciously reflect is the priceless value of white life. Imagine an entire town shutting down operations to mourn and search for a missing black trans woman? We can’t, because when trans women are murdered the only efforts to organize and demonstrations of rage come from within queer communities, often queer communities of color, who have historically adverse relationships with law enforcement. Black women face an escalated threat of violence due to the interlocking forces of white supremacy and misogyny. Yet the disappearance and death of black women and other women of color have historically never been met with the same uproar as with white women who meet the same ends.

It’s not that Knives and Skin is a failure because it seems more interested in the aesthetic allure of a dead girl than in drumming up indignation for the circumstances that configured her death. And it’s not that Twin Peaks was a failure because it prioritized white and cis tragedy over all others. Both Reeder and Lynch have done something profound when it comes to thinking and feeling through trauma, sexual violence, and grief. What remains important is to ask is whether each successive appearance of the dead girl trope is amounting to something, not on the individual but on the collective level. As Bolin has written, “It becomes harder and harder to subvert something that’s been used so many times.”

Have we seemed to make much progress from Fire Walk With Me to Knives and Skin? Honestly, no. But have the horrors real world misogynistic, racist, transphobic violence ceased? Even if rates of violent crime are in fact down in the United States, one disappearance or death like the kinds depicted in Lynch and Reeder’s work would be too many. The most successful iterations of the dead girl trope have grappled with these tough, interceding concerns, like race—consider Top of the Lake and The Night Of. The least successful amount merely to prodding a dead woman’s body with a stick just to see how it feels—consider every episode of My Favorite Murder. The most that I can hope is that future creators considering employing the dead girl trope take the long view of all that came before and ask, is it worth it? Does the dead girl in my story deserve this? What kind of justice, in fact, does she deserve?

copyright © 2019 Ryan Christopher Coleman

#twin peaks#david lynch#laura palmer#sheryl lee#knives and skin#jennifer reeder#fire walk with me#top of the lake#the night of#riverdale#the killing#the falcon x reader#my favorite murder#georgia hardstark#karen kilgariff#alice bolin#dead girls#essay#film criticism#film theory#film essay#how to get away with murder#true detective#true crime#film

45 notes

·

View notes

Text

With the movement that has been going on on Instagram with #challenge accepted I’ve been doing a fair amount of thinking about queer representation and support in the arts and media community.

*Disclaimer- I know the origins of #challengeaccepted and fully support alll of the work being done in Turkey by the brave women who started the movement. Women supporting women is definitelylife or death in that country and femicide is an issue across the globe. Please take the time to research the movement and it’s impact. I support them and I am not trying to take away from that cause with this post. These are just my thoughts and dilemma’s that I have been dealing with that were prompted by seeing those posts*

The #challengeaccepted hashtag has made me think more about support in all of my communities. From the city I love on and support for local businesses to the women I know and my support for their lives and success in this world. It’s made to think most about my place in the queer community and arts community and how best to support my fellow rainbows, especially in the arts and representation.

I have been delving into more and more queer spaces during this pandemic and I have begun seeing a worrying trend when it comes to representation. Of course there are the two sides of the issue in the world at large, one side that wants to see more diverse representation, not only of queer and LGBT+ characters and stories but that of female and BIPOC stories as well; and the side that sees any bit of representation as “shoving it down their throats” and “taking away from the story to push some agenda”.

Now that second side is toxic and dangerous, but I do not, and can not, speak to them or for them about this. They are convinced of their righteousness in the situation and no amount of my reasoning or logic or calm pleading can sway them from their views. They are mad and might boycott some films or tv series but as we have seen with movies like Wonder Woman, Captain Marvel and Black Panther their boycotts and noisy who I propaganda really don’t have much of an impact on the money being made or the widespread marketing of that media.

The group of people I am having a tougher time with are two fold and both the sub groups of group A. The first are the people that are content with the representation we have. Who love seeing queer people and stories and support them but don’t see the lack of diversity in that representation as a problem.

These are the people who say things like “well, I loved pose and Will and Grace is a classic, I just want to see these stories represented for a purpose.” Many of this group are film or media critical people. They argue that their lack of support for more representation comes from a place of “wanting compelling stories” or “not seeing the point of that character being gay, it’s not like he even has a love interest. Why bring it up if it’s not relevant”.

Now this group I can find more ways to reason with. Many of them are close friends of mine, many are queer themselves and have seen themselves represented. They are tired and jaded. They have seen so many “kill your gays” story lines that when a new queer character is announced they make bets as to when they will get the ax.

And I understand that. I can be one of them sometimes. I want deep and complex stories for all of the characters I see. I want a well rounded piece of media that doesn’t use the queerness of the characters as a major plot point and some tragic back story for them, but also allows that character to talk about the boy he likes. There is a balance I want to see in media that I have only found a handful of times before.

But I want more, and convincing them that they do to usually falls down to more rep means more stories which means more good solid stories. There will always be schlock, like river dale, but everyone is schlock on that show.

The second group I have a lot more difficulty with and I still can not find a way to tell them that they are hurting themselves and causing pain and damage to many people in the industry. This group is the extra progressive ones, the ones that say snidely, “I mean it’s great that Killing Eve had a female show runner and head writer each season, but the writers room wasn’t very diverse.” Or “but Glee and Will & Grace and modern family are just characatures of the queer community, stop using queerness as a code for campy.”

Now yes, Glee wasn’t the best with rep and definitely made hundreds of missteps with its characters. But the first true conversation I had with my mother about gay people was started by her telling me Kurt Hummel was her favorite character. Santana Lopez was the first time I ever saw a woman I related to that I could also relate to their dating life. And Will Truman and Grace Adler’s relationship let me feel safe for 30 minutes a week, that I wasn’t alone in my love for Sound of Music and women.

I think it comes from the cancel culture I have had a hard time wrapping my head around. Yes, we can and must do better. We have an obligation to the world and our younger siblings in the community to give them a character or story that gives them hope, that makes them feel seen; and not just as the “campy best friend” or the “victim of homophobia” that so many portrails have given them in the past.

Our history is ever changing and it is changing faster and faster. Each year the bar for representation loves closer to equity and acceptance and genuinely honest portrails. But please don’t bash the studio that took a risk and when the percentage of female head writers in Hollywood was 2% hired a female writer and staffed her writing room with more women than men. Yes, the diversity of race and sexual orientation and background on that room needs to grow. And now they have a chance to do so.

If you are in any of these groups, what are your thoughts? Are we pushing to hard for diversity that we’re sacrificing quality and substance for representation? Are we not pushing hard enough so we are losing the opportunity to hear great stories from more diverse people? Are we great where we are? What needs to change?

1 note

·

View note

Text

Commonplace Book Reflection

Olivia Keider

Dr. Richard

WGS 3298-02

29 July 2020

Studying women’s lives in other cultures inspires a profound appreciation for women (Burn, 3). This is exactly what this “Women Writing Worldwide” class has provided me with at High Point University this summer. I have always had the thought in my head, "I wonder what other women around the world are dealing with and how they are dealing with it." I now can understand the what problems women face in their cultures and change the negative perceptions people have with women’s cultural differences. Tradition is the root of where our beliefs come from and is usually followed for a lifetime. Worldwide, especially in third world countries, women want to have equal rights and opportunities, but they are faced with opposition and discrimination based on sex, culture, and religion. Undoing and fighting preconceived notions and breaking stereotypes of oppression that Western society has placed on their countries is a difficult task. I have chosen to center my individual commonplace book online in traditions of other countries and transnational third world feminisms that they represent.

Tradition, according to the Oxford dictionary, is the transmission of customs or beliefs passed from generation to generation. Unfortunately, these traditions are not only Eastern religious beliefs but are Western stereotypes too. We are taught to believe what our parents teach us, but we should not rely solely on their beliefs and opinions to lead us forward. The world and its beliefs change and evolve, and societies, whether Eastern or Western, should be doing the same simultaneously. In some ways, women all over the world have a lot in common (Burn, 7). This passage specified exactly which countries were fighting for which discriminations. The discriminations, such as veiling in Middle Eastern countries or femicide in other countries, can be used to unite women across the globe to fight for what is right. Women who veil are usually classified by Western societies as oppressed or held down by male-dominant societies. The real issue is that the women choose to veil for themselves, as a symbol of modesty, respect, and protection. In my commonplace book post, I used a few ideas that reflected reasons for veiling and opinions related to the concept. The picture I used shows a wrapped lollipop, representing women who wear hijabs and an unwrapped one with flies on it representing women who do not. A wrapped candy is more protected and desired than one that is not covered but many Western societies do not understand and learn this ideal in their own tradition. Women’s lives in other countries are structured around ending stereotypes and creating their own ways to fight for their own issues, rather than the ones that Western culture creates for them, due to the difference in traditional practices.

Feminism needs to become a global movement. A truly global feminism recognizes the diversity and acknowledges that there are diverse meanings of feminism, each responsive to the needs and issues of women in different regions, societies, and times (Burn, 8). To explain this, I used an analogy with feminism being compared to gender equality like water is H2O. They both represent the same things, although they may look or sound different. Women are not just women…we need to see all of our similarities and differences. Anyone can be called a feminist, whether that be a woman or someone who presents as a woman. The idea is to include all women, from all cultures, all traditions, and all areas of the world along with their unique experiences to fight for equality and equity. Another post that represents the ideas of feminism that I explain in my commonplace book is the photo of Isabel Allende in the Olympics with three other women. They all are the first group of women alone to carry the Olympic flag and represent not only their country but their beliefs and ideals as women. I mentioned in my Perusall annotations of her Ted Talk that Isabel Allende took a risk by talking about controversial topics in front of an audience. She mentioned names and told stories of these other women who were “rule-benders” to convince us of their passion for good change. These women, who are extremely driven, feel the need to bring themselves forward and help other feminists and people make the world a more equitable place.

Third world countries experience the most difficulty in spreading awareness for themselves, due to the lack of resources available to do so. These countries have little to no food and water, housing that is just enough to keep them safe, and are not as updated in medical care usually. Due to these factors, other nations such as the United States, begin to feel empathetic and send help and relief to the countries. These third world countries, while they do need the provisions sent and given to them, the women and children are fighting for more than just nutrients. The women are fighting for their children and their own lives, as I explain in the quote by Mahatma Gandhi: “Any young man, who makes dowry a condition of marriage, discredits his education and his country and dishonors womanhood.” Dowry, especially in societies like these, cause huge financial burdens to the families and leads to crime against the woman who is married, such as abuse, neglect, and potentially death. Due to the large amount of people who want to follow the initial tradition of India’s dowry, even though laws have been passed to make it illegal, still practice it with no consequence. The tradition of dowry leads to women and their families killing off the children they have that are girls, since they are seen as a burden and of no use to the family name. I talk about how Mahatma Gandhi is very influential in India’s community, and seeing a prominent man say this message may change another man’s mind about taking dowry. This could eventually become a large movement to benefit all women and their families in countries such as India. Ultimately, the women and children who need more than just food cannot explain and fight for their other needs, such as safety and security. Western culture and society have been taught that their “major” issues are lack of supplies. The true major issue is the lack of listening and deeper thought from societies that can actually help save lives.

The main post that focuses the most on my topic is the quote “The most dangerous phrase in the language is we’ve always done it this way.” This phrase, as I mention in my caption for the post, is not ideal for society today. We cannot expect to change for the better and modernize if the world fears moving away from tradition or refuses to understand others’ traditions. We have to find a way to be critical of practices that are harmful to women, but understand that the issues of greatest concern to women in our country may not be the major issues of concern to women in other countries (Burn, 9). Another post I made is of women in handcuffs who have statements of their “crimes” behind their back. The women are of all different cultures and religions, and all treated poorly and are unable to stand up for themselves. I state that in the world today, feminism is becoming a movement allowing for many of these women to be able to stand up for themselves and their beliefs within their culture. This modernization and branching from tradition are important for women in third world countries to be able to potentially change their societies’ and other societies’ beliefs on certain ideals.

Overall, the ten individual commonplace book posts I made reflect harsh feelings towards the treatment of women in other countries. This mistreatment has been justified for many years through the use of tradition in many third world countries. Spreading the word about these nations with disparities and inequalities towards their women could be what changes their society forever. I talked about this issue in my Perusall annotations for Chandra Mohanty’s Under Western Eyes article. As soon as I read this, I instantly flashed to Dr. Richard's class lecture about losing the identity between a "woman" and "women." The difference is huge! Comparing an individual in the same way as an entire group can be misleading, cause many misunderstandings, lead to stereotypes, and eventually become oppression. This is exactly what is going on in the United States and other countries for women. Every woman and every countries' situation and experience are unique and different in its own way and should be respected and understood. Not all "women" are in need of the same representation in the same areas. Some need representation politically, others physically or sexually, some mentally and socially, and these differences, are what keep implications of "women" being similar across nations from being assumed. The world needs to look at the intersectional and transnational analysis between "women" to understand what each "woman" traditionally experiences on a daily basis and make a change.

0 notes

Text

How Trump Created a New Global Capital of Exiles

New Post has been published on https://thebiafrastar.com/how-trump-created-a-new-global-capital-of-exiles/

How Trump Created a New Global Capital of Exiles

An asylum-seeker outside El Chaparral port of entry in Tijuana, Mexico, waits for his turn to present to U.S. border authorities to request asylum. | GUILLERMO ARIAS/AFP via Getty Images

Jack Herrera is an independent reporter and photojournalist covering immigration, refugees and human rights. His writing has appeared in Pacific Standard, The Nation, GEN magazine, Columbia Journalism Review, USA Today and other publications.

TIJUANA, Mexico—If you go early in the morning to the plaza in front of El Chaparral, the border crossing where a person can walk from Mexico into the state of California, you’ll hear shouts like “2,578: El Salvador!” and “2,579: Guatemala!”—a number, followed by a place of origin. Every day, groups of families gather around, waiting anxiously underneath the trees at the back of the square. The numbers come fromLa Lista, The List: When a person’s number is called, it’s their turn to ask for asylum in the United States.

These days, the most common place names shouted are Michoacán or Guerrero, Mexican states where intense cartel violence has sent thousands fleeing northward—occasionally, they’ll call Guatemala, El Salvador or Honduras, countries where pervasive poverty, gangs, drugs and femicide have done the same. But every so often, the name of a different, more far-off country is called. In the span of just two weeks late last year, a list-keeper called out a number, in Spanish, followed by “Rusia!” They also called out numbers for people from Armenia, Ghana and Cameroon. Asylum-seekers from the Democratic Republic of the Congo crossed, as well as people from Eritrea. One day, the list-keeper called out “Turquía!” and a Turkish family rushed forward to claim their spot. The family was escorted by Mexican immigration officials over the pedestrian walkway into the United States, where they told Customs and Border Protection agents that they had, like everyone else, left their home country fleeing for their lives.

These people were the lucky ones. They had managed to persist in Tijuana, waiting until the day they finally heard their numbers called. Others haven’t been so fortunate. With The List’s queue regularly stretching longer than six months, many migrants fall victim to predatory robbery, kidnapping or murder before they can find refuge; others find the wait in one of the most dangerous cities in the world simply unendurable.

When Americans think of the people crossing the southern border, they might imagine Mexicans or Central Americans—or, even more generally, Latin Americans. But migration, both legal and illegal, from Mexico into the United States is incredibly international. In the course of 2018, Border Patrol agents apprehended nearly 9,000 Indians, 1,000 Chinese nationals, 250 Romanians, 153 Pakistanis, 159 Vietnamese people and dozens of citizens of over 100 other countries. Fifteen Albanians and seven Italians were stopped trying to cross the southern border, as were four people from Ireland, a single person from Japan, and three people each from Syria and Taiwan. Border Patrol even apprehended two North Koreans on the border in 2018 who were separately attempting to cross into various parts of Texas.

Now,one of the most direct effects of Trump’s border policy is that thousands of foreigners from all over the world have found themselves unexpectedly stuck on the southern border. Since 2017, President Donald Trump has turned the country’s immigration system on its head to deter Central American asylum-seekers. But policies meant to address Guatemalan or Honduran migrants have also affected Jewish people fleeing persecution in Hungary; Syrians escaping civil war in their home country; and LGBTQ people fleeing Vladimir Putin’s homophobic regime in Russia. The effects of U.S. border policy are not confined to northern Mexico. They reverberate around the world.

When I met asylum-seekers at El Chapparal and around Tijuana, most of them told me that they’d been waiting in the city for months. Even though U.S. law says that anyone who claims to be fleeing for their lives should be immediately admitted to a port of entry for vetting, under the Trump administration, Border Patrol has started a controversial policy of “metering.” Now, agents accept only a set number of asylum-seekers each day and send the rest back. In Tijuana, they accept around 20 to 60 people per day, while thousands are left waiting and more are constantly arriving. That’s how The List was born: Migrants themselves began keeping a ledger as an attempt to create a fair waiting system—a virtual line—to get past the manufactured bottleneck.

But that wait may now be for nothing. In July, the Trump administration announced it would no longer accept asylum applications from people who transited through a third country on their way to the U.S. Anyone who traveled through Mexico or another country that wasn’t their place of origin without first applying for asylum there could be returned automatically. (The asylum restriction, immediately challenged in court, has been temporarily upheld by the Supreme Court pending a final decision).

At a time when the total number of refugees around the globe has reached the highest level since World War II, the United States has refashioned the immigration system in a way that forces those fearing for their lives in their home countries to put their lives at further risk on the way to safety. Many potentially legitimate asylum-seekers who once might have found at least temporary refuge in the United States while their applications were being reviewed are now made to undertake a harrowing and dangerous journey across the world, only to be forced to wait in Mexico’s borderlands—and less likely than ever to be allowed in later. Across the border, Mexican cities like Tijuanaare struggling to deal with a shifting crisis of their own, with thousands of desperate people, many stuck in a foreign country they never intended to stay in, struggling to survive in a region afflicted by its own intense violence and poverty.

That’s Daniel’s situation.(Out of an abundance of caution, I’m using pseudonyms in place of current asylum-seekers’ names.) An English teacher from Ghana, Daniel has been waiting in Tijuana since June to cross at El Chaparral. This past October, Daniel told me his number on The List was 4,068. At that time, the numbers being called were in the high 2,000s. By New Year’s Day, the numbers being called on the list were still below 3,800, and Daniel was still waiting to cross.

I met Daniel in the small church shelter where he sleeps in a ramshackle neighborhood built on the steep side of Cerro Colorado, the enormous hill that rises out of the center of Tijuana. As we sat on a bed in the pastor’s room, the 42-year-old spoke openly, though he initially remained vague about the reasons he left Ghana.

“I came here because I had a problem with some people. If I hadn’t left that place, it wouldn’t be good,” he said.

Daniel told me his story is “very sad,” and he didn’t want to burden me with the details, but he had to leave the country very quickly. He spoke in a voice that was soft but gravelly and rough: He said he has throat cancer, and I could hear it was painful for him to speak. But he still had the gentle tone and mannerism of a teacher. When he noticed me misspell his real name in my notebook, he quietly reached over and pointed out where an “e” should have been an “a.”

Mexicans call asylum-seekers like Daniel extracontinentales—a word for immigrants who come from outside the Americas. Daniel has been one of the many extracontinentalesbiding his time in Tijuana, waiting for his turn to cross into the U.S, and he thinks he’s still got months before they call his number on The List.

Life for extracontinentalesin northern Mexico can be tough. While thousands of people from outside the Americas arrive on the border each year, most shelters are equipped to house Latinos. Staff at migrant homes around the city told me they had trouble providing the right food for foreigners, especially those with religious dietary restrictions. There can also be a cultural disconnect. Though Daniel is friendly and approachable, he still has a look of distance to him, a gulf created by language and custom. Each night, he sleeps in a small bunk bed in a room with about two dozen other people, all from Mexico or Central America. No one in the shelter speaks any English besides the church pastor, so Daniel’s evenings are mostly quiet. He smiles when others make eye contact with him, but most people quickly look away. While in the shelter, I heard a Central American man use a demeaning word for black people in Spanish to describe Daniel.

As wait times to cross the border grow longer, many foreigners live in precarious and unstable conditions in Mexico. In many ways, the situation has become a humanitarian crisis.

Many foreigners I met in Tijuana—people from Ghana, Yemen, Jamaica, Cameroon, India—talked about experiencing loneliness, isolation, and racism. They told me Mexicans are generally welcoming, tolerant and respectful, but the country is still a hard place to be for non-Latinos—especially those who do not speak fluent SpanishorEnglish.

Some get by using a phone to translate into Spanish, but most foreigners have trouble integrating, especially when it comes to finding work. Many wind up working long hours in the factories on the outskirts of the city, or in other jobs involving physical labor. At many car washes around the city, it’s become a common sight to see groups of Africans—Ghanaians, Cameroonians, Congolese—cleaning cars, the very same kind of cheap but steady labor that many Mexican migrants resorted to in Southern California in the 1990s and 2000s.

For people like Daniel, the wait might become permanent. In July, the Trump administration announced it would no longer accept asylum claims from anyone who transited through a third country on their way to the United States unless they applied at each country they passed through first, effectively making allextracontinentaleslike Daniel ineligible. Though U.S. officials say asylum-seekers can simply seek refugee status in Mexico, journalists and human rights groups have documented many cases of asylum-seekers facing kidnapping, rape, robbery and murder in that country.

“Mexico is a good country,” Daniel says. But he still wants to make it to the United States, where he hopes he might finally be able to find stability, safety and a community.

Though the experience of being a foreignerin northern Mexico can be isolating, Tijuana is a decidedly international city. Long a transit point, it’s become a milieu of cosmopolitan culture. Russians have been arriving in the city since the late 1940s (many fled the former USSR), and there’s even a popular taco stand called “Tacos El Ruso” with a cartoon on the wall that proclaims, “Que Rico Takoskys.”

This multinational characteristic is particularly vivid in the city’s only mosque, a small, plain building in the city’s west, not far from the Pacific Ocean. During a Friday prayer in October, I watched as the imam began his sermon in Spanish before transitioning to English—though many of the men gathered didn’t speak either language.

“We’ve got people from Egypt, Turkey, Russia, Tajikistan, Pakistan, Afghanistan—I mean, everywhere. You name it, we’ve got it,” Imam Omar Islam, a Mexican-born convert, told me. He says many of the people he meets in the mosque have come fleeing conflict in their home countries, trying to make it to the U.S.

The men mostly arrive in groups with their compatriots (Egyptians with Egyptians, Indians with Indians), but during prayer the group comes together as one, and at the end of the imam’s sermon, they rise to greet one another. There was a young man who escaped civil war in Yemen who shook hands with a group of West Africans, including Emmanuel, a man who fled multiple homophobic attacks in Ghana.

Today—especially as the Trump administration cracks down on the asylum process—many migrants who first intended to go to the U.S. have decided to stay in Mexico. Some seek humanitarian visas, while others try their luck as undocumented immigrants.

Emmanuel told me has no desire to stay in Tijuana. With clear west African features, he stands out, and he says he’s been beaten and robbed multiple times by thieves who target the vulnerable migrant population.

“I can’t stay here. It’s too dangerous,” he said.

In 2018, Tijuana was, by some measures, the murder capital of the world. And, according to reports by U.S.-based advocacy organization Human Rights First, “refugees and migrants face acute risks of kidnapping, disappearance, sexual assault, trafficking, and other grave harms in Mexico.” Besides the inherent vulnerability of being itinerant, asylum-seekingextracontinentalesalso can routinely face racism and anti-LGBTQ violence in Mexico.

Emmanuel plans on crossing the border and asking for asylum in the United States, but his number on The List is weeks, if not months, away. After his last robbery, he says he can’t afford rent. He’s desperate, and unsure what to do. For many of these extracontinentalesstalled in the north of Mexico, the U.S. border is simply the final obstacle at the end of an immense odyssey.

There’s a fairly straightforward reason why so many people from around the world end up in northern Mexico, even though their ultimate destination is the United States: visa restrictions. For many people, it’s impossible to fly straight to the U.S. without a visa, so many asylum-seekers fly into Latin American countries with the plan to travel northward.

For people with stronger passports, like Russian, Indian and Chinese nationals, it’s possible to fly directly into Mexico. Many of theseextracontinentaleshave landed first in Mexico City or Cancún, where they masquerade as tourists before making their way to the border. (The rate of arrival is higher than you might think: On a single Monday when I was in Tijuana, six Russians and two Chinese nationals were detained at the airport on charges of traveling with forged or improper documents; they were promptly returned.)

But many people from African and Middle Eastern countries have trouble securing travel even to Mexico. So, for many forced migrants—like Daniel and Emmanuel—the journey through the Americas begins much further south.

Daniel says he never had any intention of coming to the U.S. originally. He just needed to leave Ghana. In a rush, he flew to one of the few countries on the planet where Ghanaians could travel without a visa: Ecuador. (Daniel arrived in April, three months before Ecuador added Ghana to a very short list of countries whose citizens can no longer arrive without a visa.) He landed in Quito, the country’s high-altitude capital in the Andes, without any plan.

“When I got to Ecuador, communication was a real problem. I speak English, but I have never traveled to the American continent. So when I got there, the language—Spanish—I didn’t understand anything,” Daniel said. “I asked someone, ‘Which country in this area speaks English?’ And they said, “Around here? Nowhere—unless you go to the United States.’”

Daniel says he didn’t know anything about the U.S. “All I knew is that there is a country called United States, and that it’s very good country,” he said. But, after a week in Quito, he made his choice and caught a bus toward Colombia, the first leg in a long journey to Tijuana.

On the buses he took, Daniel spoke to other migrants—many from Venezuela but also others from Cameroon and the Democratic Republic of the Congo—all heading northward. In recent years, thousands of people from around the world have made the same long and arduous journey as Daniel, from a South American country to the U.S.-Mexico border. (Ecuador, which has some of the freest visa requirements of any nation, is perhaps the most popular starting point.) From there, they travel down out of the mountains into Colombia, and then to the border with Panama. At this point, the journey becomes incredibly perilous. Many do not survive.

There is no road between the jungles of northern Colombia through the swamps into central Panama. Traveling on foot, northbound migrants must trek first over cloud forest and then across 50 miles of marshland, through a stretch of sparsely populated wilderness called the Darién Gap. The trip is, by all accounts, brutal. Reporting from northern Mexico in the past year, I’ve spoken with asylum-seekers from Ghana, Cameroon, Venezuela and the Democratic Republic of the Congo who all said they had made this trek. The stories they tell are harrowing: People die from snakebite or from drowning. Many eat nothing but uncooked rice for the week it takes to transit the Gap.

Emmanuel grew silent when we started talking about the journey through the swamps in Panama. He asked to pause the interview and later explained he was overcome with guilt because he didn’t stop to help people he saw dying. He barely had enough strength to carry himself forward.

“I can’t let my mind go back there,” he told me, shaking his head repeatedly.

Along the migration routes, human traffickers, kidnappers and robbers prey on travelers. People get robbed in every country, but every person I spoke with, without exception, said they were robbed at gunpoint by bandits in the jungle in Panama.

Daniel says that if he had known exactly how horrible the journey would be, he might not have made it. But many of the people traveling northward do know how arduous their travel will be and continue anyway. They simply have too much to lose if they turn back.

For Emmanuel, the situation back in Ghana became so severe that he chose to make the journey northward from Ecuador not just once, but twice. After he first fled homophobic violence in Ghana in 2016, Emmanuel made it to the U.S. border and crossed at the official port of entry. As he argued his asylum case in court, he remained in Immigration and Customs Enforcement detention. He says he learned his English while there. After almost two years, Emmanuel was hopeless and depressed. He decided he couldn’t stay locked up anymore and chose to give up on his asylum case. ICE deported him back to Accra.

Once returned to Accra, Emmanuel was attacked again by the men who originally persecuted him. Emmanuel says he’s not gay, but he welcomed LGBTQ patrons into the mechanic shop he ran. Nevertheless, people in his community accused him of being gay and tried to kill him, he says. He showed me huge scars on his belly from stab wounds and a video someone filmed soon after he was returned to Ghana showing him bloody and unconscious in a crowded hospital. Fearing death, Emmanuel escaped again and flew back to Ecuador this past spring.

He says the journey is the hardest thing he’s ever done. But still, he chose to make the trek a second time. He says he had no choice. In Mexico, he showed me that he still gets threatening phone calls and WhatsApp messages from unknown contacts. He is certain he’ll be killed if he ever returns.

The people making the northward journeyto the United States have left behind some of the world’s most severe strife and brutality. In Tijuana during the past year, I’ve met English-speaking Cameroonians who told me how they fled violence at the hands of their country’s Francophone majority (an ongoing campaign of repression that some humanitarian organizationsbelieve amounts to ethnic cleansing). They shared stories of torture and rape used as weapons of war. I met Russians who arrived on the southern border in recent years after escaping the persecution of LGBTQ people under Putin’s regime. People have fled war in Syria, Iraq, Yemen, Afghanistan and Central African Republic. Thousands of Hungarians and Romanians have made their way to the southern border after fleeing increasingly violent anti-Semitism and growing authoritarianism. And in the past four years, the U.S. has seen a fast-growing number of Indian religious minorities cross the border, after leaving behind burgeoning Hindu nationalism in their home country.

At the same time, the Trump administration has claimed that the promise of refugee status has become a “pull factor” that has drawn to the U.S. people from around the world with dubious asylum claims. What the U.S. needs, the administration argues, is a deterrence-first policy. But it’s hard to imagine a deterrent more onerous than the journey from Ecuador to the southern border—a punishing gantlet that some like Emmanuel have been forced to make more than once.

Thanks to the Trump administration’s new “third country” asylum restriction, declaring asylum in the U.S. now comes with a dramatically increased risk of deportation back to one’s home country, a terrifying prospect for so many.

However, new immigration policies have delayed effect, one felt acutely here on the border: Many people trying to reach the U.S. were alreadyen routewhen the newest restriction was announced in July. Emmanuel was making his way through Guatemala; Daniel had been in Tijuana less than two weeks and had already taken a number from The List. Now, both men are stuck in Tijuana with limited choices.

Even if they decide to remain in Mexico, their fates are far from certain. Besides the dangers of robbery and violence, Human Rights First has documented cases of Mexican officials deporting asylum-seekers without due process. And, under pressure from the Trump administration, Mexico has begun dramatically expanding its own deportation machine. Just during a few days I was recently in Tijuana, Mexican officials deported over 300 Indian nationals back to Delhi on a flight from Mexico City.

In October, I visited a Mexican immigration office in southern Tijuana that’s been converted into a makeshift detention center.

“Which countries are detainees inside from?” I asked a janitor on her smoke break.

“Every country,” she told me. “Peru, Haiti …”

“United Nations inside there,” someone else joked.

When I asked the woman what the conditions were like inside, she just shook her head and raised her eyebrows. As she looked over her shoulder nervously, she motioned silently in a clear gesture: “not so good.”

The threat of detention might persuade some foreigners to give up, to leave Mexico. But for many people, like Daniel or Emmanuel, going home is not an option.

The promise of the United States, of freedom from persecution or violence, persuaded the two Ghanaians and thousands like them to travel tens of thousands of miles, across oceans and mountains. But steps away from the southern border, they learned that the door had been slammed shut. Tijuana was never meant to be the final destination for Daniel or Emmanuel or so many other asylum-seekers. Rather, the city is just a place they’ve wound upatrapado—stuck.

Jorge Armando Nieto contributed to this report.

Read More

0 notes

Link

On Tuesday, October 4, DJ and model Ximena Gama posted several graphic pictures on Facebook that soon set Mexico City’s indie music community ablaze. In them, Gama’s face and arms appear bruised and her nose is bandaged. In the post, Gama accuses ex-husband Sabú Avilés of assault. Avilés, a member of garage rock bands Los Explosivos and Los Infierno, took Facebook to deny the accusations, and soon a larger dialogue regarding gender violence and the responsibility of music journalists mushroomed in the Mexican indie community.

According to Gama, on September 3, Avilés hid the household’s phones and computers, locked her in her apartment, and proceeded to assault her for five hours. Her post has since been deleted and Facebook suspended her account for violating guidelines.

Ximena Gama details sexual assault accusations on Facebook (part 1).

Ximena Gama details sexual assault accusations on Facebook (part 2).

Avilés also made a statement on Facebook regarding the accusations. He confirms that “the bomb exploded” on September 3, but said it was “not as bad as they are making it seem.” He states that Gama sued him for child support, which he claims he has not neglected. He suggests Gama’s statements are “beyond exaggerated.” Avilés later deleted his Facebook account.

Sabu Avilés denies accusation on Facebook (part 1).

Sabu Avilés denies sexual assault accusation on Facebook (part 2).

Shortly after, Los Infierno shared a press release distancing themselves from Avilés and reiterating their commitment to fighting gender-based violence. In a separate post, they wrote that Avilés has parted ways with the band. Both Los Infierno and Los Explosivos’ Facebook pages have since been deleted. When Remezcla reached out to Avilés for comment, he declined to address his current involvement with Los Infierno.

Los Infierno press release.

Los Infierno Facebook post.

Avilés responded to Remezcla’s interview request with a statement that he posted on his reactivated Facebook account on Friday, October 7. In it, he denies Gama’s accusation that the attack qualified as sexual abuse in the second degree and denounces her for child neglect. “I bring this to attention due to the defamation expressed a few days ago on social media on behalf of Ximena Alejandra González Gama…who, with photographs that do not correspond to what happened on September 3, 2016…has falsely accused me and characterized me as a violent man, all of this without knowledge of the truth.” According to Avilés, each of the photos Gama posted on Facebook misrepresents her whereabouts and physical condition following the alleged assault.

Exploring the world in which the music is conceived and materialized is one of our most precious jobs.

Gama granted us a brief interview on Monday, October 10. According to her, Avilés “was caught in the act and taken to the Ministerio Público [similar to a district attorney’s office in Mexico]. I pressed charges and now he’s being sued for violence against a family member.” Of Avilés’ statement, Gama said, “I think it’s cowardice and showed a lack of respect. First [he’s] trying to defame me to justify his mental problems. It’s true; I go out because of my project Psych Out, but I have never neglected my daughters.”

Gama addressed some of his accusations in detail. “He also claims that the dates don’t add up because I had my surgery nine days after the events [and that is what is portrayed in the photos]…I looked for him [so we could] come to a settlement for child support, but he told me to ask one of my lovers for money instead…He was not set free; he posted a sort of bail which allows him to continue the legal process [while he isn’t in custody].”

Gama discussed the background of their relationship further. “It was not the first time it happened. I had been in therapy for a month, to empower myself to leave him once and for all…15 days before the events, I asked him to leave home because I had already noticed that he was relapsing into violence; I asked him for an amicable separation for the girls, but he refused to leave.”

Shortly after it emerged, Gama’s story sparked conversation among editors and writers from different Mexican publications, leaving many wondering if music journalists have a responsibility to cover stories of sexual assault and gender-based violence. For example, on October 5, Mexican website Tercera Vía posted an interview with Avilés’ former spouse Gema (who chose not to disclose her surname). In it, Gema alleges that Avilés also assaulted her during their time together, though Avilés did not comment on this case in our correspondence with him. Digger published an article stating that outlets have a responsibility to cover abuse allegations so that fans know what kind of artist they are supporting.

One of the journalists who spoke out is Marvin editor-in-chief Uili Damage, who initially stated that the magazine would not cover the case. Marvin eventually posted a news story about the case, so Remezcla reached out to Damage for comment. “It’s not that the media is afraid [of covering stories involving gender violence], [it’s that] they’re lazy. Anything concerning local musicians doesn’t give you the same cred as writing about Kanye; it’s simply not cool. We don’t have journalistic rigor because the people generating content are mere fans. People in media are amateurs and malinchistas.” As Damage explains, many Mexican media outlets approach music journalism from a lifestyle or fan perspective. Writers may not have the training to know how to responsibly cover reports of gender-based violence in the industry.

And although there are a diversity of outlets in the Mexican media landscape, not many differ in their approach to coverage. Damage spoke about how an editor could break the cycle and approach such a story in the appropriate way. “[News like this] verges on sensationalism. I’d rather leave that for the op-ed section. Speculation is not journalism, it’s gossip. We need journalists [who] put in the work and are truthful.” Later, Damage published an op-ed in which he elaborated on these ideas, and offered some data about violence against women.

Julián Woodside, a cultural critic and scholar specialized in music, has covered much of this conversation throughout the years. In 2015, he penned an op-ed arguing that alternative media outlets in Mexico are more concerned with justifying tastes than covering the actual music produced in the country. Most recently, he wrote an editorial for PICNIC Magazine arguing that music media should inform readers about music culture and social problems at large, rather than simply curating tastes.

“To take a step to denounce something like this implies strong self-criticism.”

Woodside argues that there’s a “lack of interest and initiative” in media. There’s this “idea that people don’t read and prefer photos or graphic content when this is the generation that reads the most in history…There’s also fear at an editorial level, because this subject is very ingrained culturally and it’s difficult to size as a problem within the workforce. It’s a male-dominated environment, so there’s fear that it will open a Pandora’s box. To take a step to denounce something like this implies strong self-criticism.”

About the lack of professionalism, Woodside somewhat disagrees, saying that there are professional journalists, but too many interests exist beyond journalism for those involved in it. “They serve a lot of functions at the same time; they’re musicians but also journalists, promoters, producers, managers, etc. There’s fear that if they write a bad review, then a lot of doors will shut for them in their other function as musicians. It’s easier not to stir the pot…that’s why I think many people condoned [the assault] by saying ‘it’s gossip’ and ‘it only concerns those involved.’ But no, [gender violence] is a public concern and this case involves a public figure. It’s [a] pertinent [case] in the local context.”

Ni Una Menos protest in Buenos Aires

Gama’s story comes at a time when there is increased attention to the conversation on gender-based violence in Mexico. In 2014, the National Women’s Institute reported that 47 percent of Mexican women over the age of 15 have suffered physical, sexual, emotional, and/or economic violence. The National Citizens’ Observatory on Femicide reports that six women are assassinated every day in Mexico, with killings most likely to occur in Estádo de Mexico. On June 3, 2015, the Ni Una Menos movement, which battles violence against women, held its first march in Argentina. Since then, protests have spread to Peru, Brazil, and Mexico.

As these figures attest, it’s difficult to not be startled by the volume of gender-based violence in Mexico. Music doesn’t exist in a realm separate from our sociopolitical reality, and that violence has a longtime presence in the entertainment industry. Some of the finest music journalism and criticism occurs when we ask ourselves about that context as it pertains to a finished work of art – how it reflects or reacts to local circumstances, and how conscious or not the artists are of their surrounding context. Exploring the world in which the music is conceived and materialized is one of our most precious jobs, and that includes reporting on accusations of violence, even if they are not related to the production and consumption of music per se.

As a site that has a long history of covering activism, social justice, and gender-based violence in the music industry, Remezcla finds it paramount to report such cases of sexual assault. Music brings the promise of emotional release and escape, but it has also served as an instrument of change used to denounce and criticize societal ills and create a better world. As writers, we have a responsibility to highlight music’s potential for change, and ensure that music culture does not repeat the negative patterns we find in the world at large.

If you are a victim of violence or know someone who is, seek help from organizations like Cuidarteand Mestizas.

Additional reporting by Rodrigo R. Herrera and Emanuel Rivera. Special thanks to Pablo Dodero.

0 notes