#folkloristic

Text

Innocent college girl was seduced and drilled by elder teacher

Twerking teen fucked on all fours

Kristina Rose Gets A Big Load Shot On Her Hairy Muff

Hot Dominant Babe Laura Crystal Fucks Babetta’s Fat Pussy With a Strapon!

Concupiscent blondie wih tanlines gets her hairless pussy banged

Chubby Tinder Teen Plays With Her Pussy

Gay teacher and boys porn Versatile Latino Gets Covered in Cum

Horny oriental bimbo fondles her wet vagina and gives an oral job

Perfect latin

Jayden Starr gets creampied by white Gloryhole cocks

#proathletic#garookuh#Sardo#uptrill#salopette#Staffordshire#grailing#globo-cumulus#cockstone#ivorine#folkloristic#genasi#inexcitability#bestir#demasculinised#disgenius#pullulate#sultanaship#Oedipus#turnip-sick

1 note

·

View note

Text

Tumblr Grimoire

Here is a comprehensive collection of all of the posts I've done on the occult and the spells I've done and spell resources. This will be added to over the life of the blog as well this way everyone won't have to dig for everything. And you get to learn a bit more about my practice.

Occult & Folklore Lessons

History Of Solomonic Practices

Ars Goetia 72 demons Kings

Ars Goetia 72 Demons Dukes Pt. 1

Petitioning Deities From Around The Globe

Ancient Art of Osteomancy

Curses: A History On The Dark Arts and How to Practice Them

The Enochian Language

Scrying, A History, and Guide

CELTIC FOLKLORE&MYTHOLOGY 101

Realm of Celtic Faeries

Protection From Malignant Spirits

Appalachian Folk Practices 101

Incantation Bowls

Spells and Rituals

Exorcism

Exorcism Charms

Exorcism Powder

Boundary Powder

Everlight Candles

Solarian Oil

Vincula Luna

Igni Bowls

Basic Banishment

Binding A Spirit To An Object

Malignant Spirit Binding Totem

Pseudo Moon Water

Medicinal Herbs & Remedies

Tincture For Sleep

Salve For Minor Injuries

Grimoire Reading List

this is added to periodically it's free pdfs you can download

Informational Joke Posts/Answered Asks

Greek Sacrifice Traditions

Is Mana Real?

Sonneillon The Demon Of Hate

Demonolatry for Lesser Known Demons

Do you have to be born with magic, or can anyone learn it?

Navigating the Divide Between Legitimate Academic Study and Occult Fiction

Can magic heal physical injuries or illnesses, or is that just stuff they show in movies?

Services Offered By WanderingSorcerer

Get Early Access To All Of My Work On Magick and The Occult

Spellwork and Tarot Reading Prices Listed Here

One On One Occult Lessons With WanderingSorcerer

☕If You Love My Blog Consider Buying Me A Ko-Fi☕ 😊

#occult#occultism#occultist#demons#ars goetia#solomonic magick#magick#witchcraft#folklore#folklorist#magi#magus#grimoire#grimoires#witch#witchblr#witches#witchythings#witchlife#pagan witch#WanderingSorcerer#herbalist#plants and herbs#herbology#herbalism

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Misunderstanding Lucifer from the Sandman series and why Gwendoline Christie is the right choice (an art historian and occultist's opinion)

I am writing this post as I'm absolutely baffled by the issues people seem to have with the portrayal of the character of Lucifer in the Sandman series. For some reason people find it problematic that the fallen angel is played by Gwendoline Christie, a powerful and androgynous-looking woman, but there is seemingly no problem with Lucifer being played by a black-haired man in the nightclub business (Tom Ellis in the Netflix series 'Lucifer'). Don't get me wrong, Tom Ellis is entertaining and wonderful to watch, but that particular version of Lucifer is neither canon when it comes to the comics nor does it have anything to do with the actual angel Lucifer.

Angels are genderless beings and they have always been portrayed as androgynous in the history of art. Multiple literary sources, including grimoires (books with supposed instructions on how to summon these beings and many others), state that angelic beings as well as demons are able to change their appearance. Many of those forms they might take aren't even humanoid and they can choose not to show any physical form at all. They aren't corporeal beings, the fact that they do take on any resemblance of a physical form is just so humans can understand them better. That's why we've been painting them as human-like ever since the early times of human civilization. What we make to be similar to us is what makes it comprehensible. Portraying beings from other dimensions/realms as human-like but with androgynous features is a way to show they don't belong in the physical dimension, as gender is likely a non-existent concept in other realms of existence. Androgyny of mythical beings, therefore, emphasizes the fact they are different than physical beings such as humans.

Therefore, when portraying an angelic being in art, or in any type of media, making them androgynous is making way for their essence to come through. In a way, the same applies to the way elves are portrayed as ethereal and androgynous since they don't have to be corporeal beings at all, at least when it comes to folklore. I know this opinion might not be understandable to others or it might sound controversial, but I believe that not portraying an angelic being as androgynous and not showing any signs of their divine origin (these include mannerisms that emphasize their etheriality for example, a cadence in their voice that is different etc.) is a huge missed opportunity that might rob these interesting mythical beings of what they are. Not making angels feel like angels beats the point of having an angel character (in a movie, series or video game for example) in the first place.

This is why Gwendoline Christie is the right choice. At a height of 6′ 3″ (1.91 m), captivatingly pale. androgynous with a powerful specific sort of grace and presence - a perfect 'vessel' for the Morning Star. What's more, she understands the importance, complexity, grandeur and the mythical dimension of the figure of Lucifer, as well as the whole 'spirituality' of the Sandman universe which is rather evident from her approach to this role and the interviews she has given so far. I might go so far to say that, even though the Sandman series isn't even out yet (though there is some footage available already), the casting of Gwendoline as Lucifer feels right just as the casting of Lee Pace as Thranduil in the Hobbit felt right and I consider the character of Thranduil to be the best portrayal of a humanoid mythical being on TV. Lee felt like an elven king, moved like an elven king, spoke like an elven king and radiated an energy of the dimension the elven king might have come from (I'm talking about the folkloric 'Otherworld' where elves supposedly live). I feel the same might apply to Gwendoline and Lucifer.

As an occultist, art historian, anthropologist and someone who is rather fond of the figure of Lucifer, I am looking forward to seeing how Gwendoline interprets him. Finally, we might get something completely different from a frequently portrayed 'demonic' side/version of this important mythical character. We might just see the Light Bringer who has not forgotten his divine origin.

- Heidi (@theatrum-tenebrarum)

Gwendoline Christie as Lucifer (The Sandman series on Netflix, out 5th August 2022)

#lucifer#lucifer morningstar#thesandman#sandman#mythology#arthistory#angels in art#characters#neil gaiman#gwendoline christie#comics#thranduil#elves#folklorist#luciferian#occult#occultism#witch#magick#esoteric#myths#myth#folklore#rant#gender#netflix#netflix series#anthropology#androgyny#theoccultinpopularmedia

6K notes

·

View notes

Text

i need y'all to know how much i love my husband and his definition of a 'joke gift'

he went shopping to pick up a gift for his upcoming staff party, they do yankee swap every year (the game where you unwrap gifts one by one and people trade them in an attempt to get the thing they want)

and he was like "btw i got you a joke gift" so i was expecting something small n' silly to tide me over until actual christmas

Y'ALL WHERE'S THE JOKE-

HE DEADASS JUST BOUGHT ME THE PHYSICAL BOX SET OF ROBERT FAGLES' TRANSLATIONS OF HOMER??? THIS MAN ??? HE KNOWS ME TOO WELL, HE KNOWS WHY THIS IS HILARIOUS BUT I ACTUALLY LOVE IT SO MUCH LMAOO

#everyone say 'thanks anthony'#can i call myself a folklorist now#<<< for legal reasons this is a joke#but fr this is amazing#i just paid off my new PC so i'm waiting for all my files to sync up with the cloud to move them over#so this is gonna make for a good passtime#today's been an awesome fucking day omg#greek myth#greek mythology#the odyssey#the iliad

260 notes

·

View notes

Text

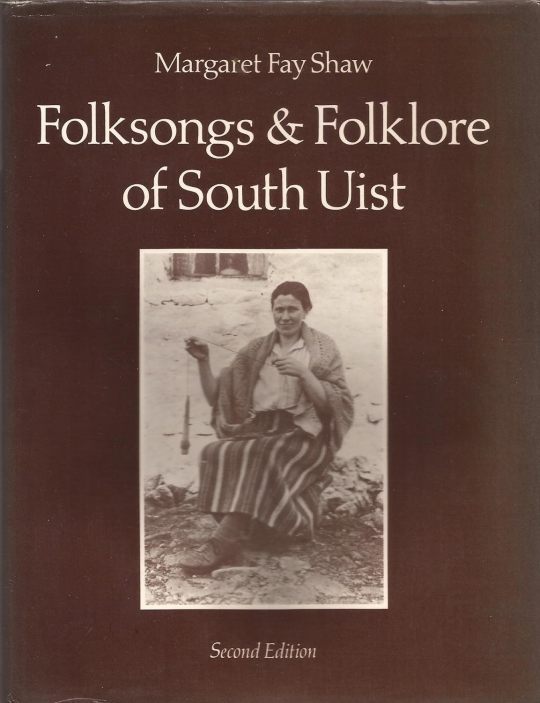

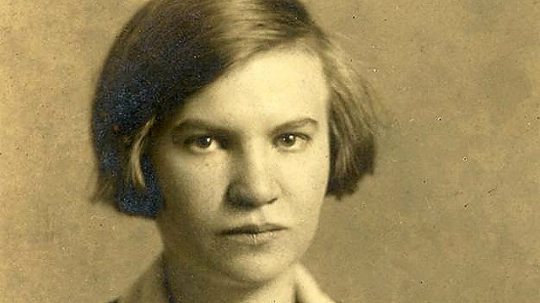

November 9th 1903 saw the birth near Pittsburgh of Margaret Fay Shaw, the American writer who did much to record the music and culture of South Uist.

Margaret Fay Shaw was one of the most notable collectors of authentic Scottish Gaelic song and traditions in the 20th century. The arrival of this young American on the island of South Uist in 1929 was the start of a deep and highly productive love affair with the language and traditions of the Gaels.

Shaw was also an outstanding photographer, and both her still pictures and cinematography contributed to an invaluable archive of island life in the 1930s. She met the folklorist John Lorne Campbell on South Uist in 1934; they married a year later and together helped to rescue vast quantities of oral tradition from oblivion.

She came of Scottish Presbyterian and liberal New England stock. The family owned a steel foundry in Pittsburgh and her parents were cultured people. Margaret was the youngest of five sisters and her early years were idyllic. Her first love was for the piano and she continued to play throughout her life.

By the age of 11, however, she was orphaned and obliged to develop the independence of character which was to lead her into a life's work far removed from her upbringing. At the age of 16, she made her first visit to Scotland at the invitation of a family friend and spent a year at school in Helensburgh, outside Glasgow, where she first heard Gaelic song.

Wanting to hear it in its "pristine" state, in 1924 she crossed the Atlantic again, this time engaging in an epic bicycle journey, which started in Oxford and ended at the Isle of Skye, where she remained for a month. It was during this trip that she began to use photography to earn a living, selling prints to newspapers, and magazines such as the Listener.

But it was not until she arrived on South Uist that she found her spiritual home. She was invited to the "big house" in Lochboisdale for dinner, and two sisters who worked there, Mairi and Peigi Macrae, were brought in to sing for the company. Margaret had never heard singing like it. For the next six years, she became their lodger and dear friend. They shared with her all of their immense stock of oral tradition which she faithfully transcribed, learning Gaelic as the work proceeded.

Her most important published work was Folksongs And Folklore Of South Uist, which has never been out of print since it was first published in full by Routledge and Kegan Paul in 1955. Not only was it a scholarly presentation of the songs and lore which she had written down during her sojourn on the island, but also an invaluable description of life in a small crofting community during the 1930s.

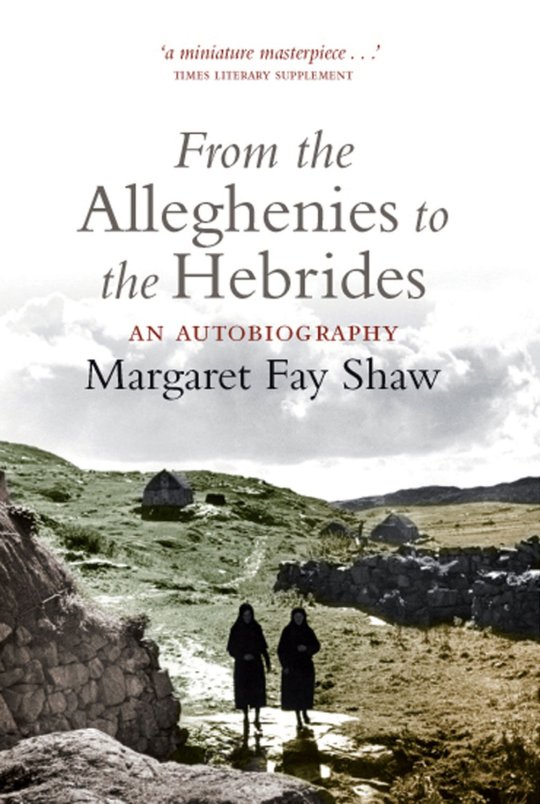

This classic work was undoubtedly the centrepiece of Shaw's career, though she also wrote several other books, including an autobiography, From The Alleghenies To The Hebrides.

On the neighbouring island of Barra in the early 1930s, an extraordinary social set - a kind of Bloomsbury in the Hebrides - had developed around the presence of Compton Mackenzie. One of his closest collaborators was John Lorne Campbell, who came from landed Argyllshire stock and had developed his interest in Gaelic at Oxford.

The two patricians set about producing The Book Of Barra, a collection of the island's history and traditions, to raise funds for an organisation called The Sea League, which they had established to campaign for the exclusion of trawlers from Hebridean waters.

Hearing great reports of an American woman's photography on South Uist, Campbell crossed over by ferry to seek her involvement in illustrating The Book Of Barra. He walked into the Lochboisdale Hotel one rainy evening in 1934 and found Shaw sitting at the piano; a suitably romantic initiation to a relationship which was to last for more than half a century. They married the following year and made their home on Barra until, in 1938, Campbell bought the island of Canna, where they lived for the rest of their scholarly lives. The island was given to the National Trust for Scotland in 1981, and John Lorne Campbell died in 1996.

There was nothing dry or academic, however, about Shaw. She travelled regularly to America until her late 90s. The fearsome ferry journey between Mallaig and Canna was regularly undertaken with equanimity, and she fortified herself to the end with the finest Kentucky bourbon. Her love of the Hebrides was, above all, for the values and lifestyle of the crofting people, and, particularly in South Uist in that 1930s heyday, it was deeply reciprocated. It is there that she will be laid to rest.

During her latter years she stayed at Canna House until her death at the grand old age of 101 in 2004.

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

Sherlock Holmes was an otherworldly creature indeed. I am no man of superstition, although I vaguely remember my grandmother’s tales of daione sìth. Holmes did not distinctly resemble any of the fair folk, these light, ethereally beautiful golden-haired men and women, and yet somehow he gave the same impression. His smooth, almost catlike movements reminded me of cait-sìth and, in all honesty, during investigations he often was the very picture of a predator pursuing the prey or cat playing with mice. I could easily imagine him in the highlands of my homeland, windy and boundless, as to my mind he had the soul of Scottish winds, but I also understood perfectly well that there was no place for him anywhere except in London, hustling and bustling and pulsating with life, crimes and mysteries.

He was not completely detached from the human world, basically having an excellent understanding of human affections, related to the motives of crimes, such as love or envy, though his knowledge clearly came from prolonged observation rather than from personal experience. He was wise enough to seek my aid when something eluded his understanding, which I prefer to consider as a sign of trust on his part.

He was too theatrical or too aloof at times — traits that I mostly attribute to the eccentricity inherent in genius. He also aged much more slowly than me, but this could easily be associated with our slightly spreading ages and his lack of habit of taking anything too personally, which I am often guilty of. Although in the decade we knew each other, I turned almost half gray, and he remained largely the same, except for a couple of new wrinkles and heavier bags under his eyes.

His voice was the voice of a siren or ben-varrey and he had a natural gift of instantly capturing the attention of everyone in the room with the help of said voice and some kind of internal magnetism, which made people instinctively trust him and obey him.

And yet my favourite of his many noble traits I dedicated myself to immortalise was perhaps his benevolence. With such a mind, such power, it would be too easy to use it for evil, something we had unfortunately seen too many times. His gaze on me which I felt quite often was never heavy or insolent and had not ever bothered me. Clients — those at least who seemed nice and did not irritate him immediately — he treated with kind patience, amiable interest and generous if sometimes mannered hospitality, being rude not out of intention to offend, but simply out of his energetic, eccentric nature.

“I am afraid I have accidentally enchanted you, my dear friend", he suddenly said, somewhat sadly and apologetically, one quiet evening on Baker Street. “That kind of devotion that you show to me cannot be expected from any man under normal circumstances.”

“That kind of devotion,” I thought to myself ruefully later that night, “has nothing in common with sidhe’s enchantments.”

This is my first attempt to capture Jeremy Brett's magnificence, and I feel like I haven't done him justice, so there will probably be other takes. Also first attempt in publishing something on Tumblr and nearly first — in writing in English, so feel free to point out any mistakes.

Following a long and good fandom tradition, I consider Watson to be Scottish, hence the writing of almost all the creatures mentioned in Scots.

The cat-sith, whose existence I learned about unacceptably late and did not change anything much, is hunting in the Scottish wastelands. It has an unhealthy addiction to corpses, so it is recommended to distract him with games and riddles, as well as warmth. Doesn't remind you of anyone? However, while writing, I mostly thought about the classic sidhe, adjusted for, uh, almost everything.

I don't know myself whether he is a magical creature, think what you want. To be honest, being portrayed as a magical creature seems unfair to Holmes as a character — part of his charm for me is precisely the fact that he is human, an outstanding human being.

#granada holmes#sherlock holmes#jeremy brett#ficlet#poorly blended fairytales#sorry to all folklorists out there

74 notes

·

View notes

Text

Living my best slavic winter fairytale fantasy. Wearing traditional ukrainian shawl and belt. Skirt is by Son de Flor and blouse from Pavietra.

#winter wonderland#cottagecore aesthetic#folkcore#dark cottagecore#folklore#dark aesthetic#traditional costume#ukrainian folklore#slavic#slavic folklore#fairytale#snow magic#folk goth#folklorist

328 notes

·

View notes

Text

The true danger of the Emily Wilde series btw is it makes me think I could stay in academia

#my spritzing myself with a spray bottle: you HATE hierarchy like that you HATE jumping through hoops and playing very specific games#you doNOT want to do this permanently!!!#also me: oohhoohoo remember how you spent years wanting to be a folklorist

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

A class on fairy tales (1)

As you might know (since I have been telling it for quite some times), I had a class at university which was about fairy tales, their history and evolution. But from a literary point of view - I am doing literary studies at university, it was a class of “Literature and Human sciences”, and this year’s topic was fairy tales, or rather “contes” as we call them in France. It was twelve seances, and I decided, why not share the things I learned and noted down here? (The titles of the different parts of this post are actually from me. The original notes are just a non-stop stream, so I broke them down for an easier read)

I) Book lists

The class relied on a main corpus which consisted of the various fairytales we studied - texts published up to the “first modernity” and through which the literary genre of the fairytale established itself. In chronological order they were: The Metamorphoses of Apuleius, Lo cunto de li cunti by Giambattista Basile, Le Piacevoli Notti by Giovan Francesco Straparola, the various fairytales of Charles Perrault, the fairytales of Marie-Catherine d’Aulnoy, and finally the Kinder-und Hausmärchen of Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. There is also a minor mention for the fables of Faerno, not because they played an important historical role like the others, but due to them being used in comparison to Perrault’s fairytales ; there is also a mention of the fairytales of Leprince de Beaumont if I remember well.

After giving us this main corpus, we were given a second bibliography containing the most famous and the most noteworthy theorical tools when it came to fairytales - the key books that served to theorize the genre itself. The teacher who did this class deliberatly gave us a “mixed list”, with works that went in completely opposite directions when it came to fairytale, to better undersant the various differences among “fairytale critics” - said differences making all the vitality of the genre of the fairytale, and of the thoughts on fairytales. Fairytales are a very complex matter.

For example, to list the English-written works we were given, you find, in chronological order: Bruno Bettelheim’s The Uses of Enchantment ; Jack David Zipes’ Fairy Tales and the Art of Subversion ; Robert Bly’s Iron John: A Book about Men ; Marie-Louise von Franz, Interpretation of Fairy Tales ; Lewis C. Seifert, Fairy Tales, Sexuality and Gender in France (1670-1715) ; and Cristina Bacchilega’s Postmodern Fairy Tales: Gender and Narrative Strategies. If you know the French language, there are two books here: Jacques Barchilon’s Le conte merveilleux français de 1690 à 1790 ; and Jean-Michel Adam and Ute Heidmann’s Textualité et intertextualité des contes. We were also given quite a few German works, such as Märchenforschung und Tiefenpsychologie by Wilhelm Laiblin, Nachwort zu Deutsche Volksmärchen von arm und reich, by Waltraud Woeller ; or Märchen, Träume, Schicksale by Otto Graf Wittgenstein. And of course, the bibliography did not forget the most famous theory-tools for fairytales: Vladimir Propp’s Morfologija skazki + Poetika, Vremennik Otdela Slovesnykh Iskusstv ; as well as the famous Classification of Aarne Anti, Stith Thompson and Hans-Jörg Uther (the Aarne-Thompson-Uther Classification, aka the ATU).

By compiling these works together, one will be able to identify the two main “families” that are rivals, if not enemies, in the world of the fairytale criticism. Today it is considered that, roughly, if we simplify things, there are two families of scholars who work and study the fairy tales. One family take back the thesis and the theories of folklorists - they follow the path of those who, starting in the 19th century, put forward the hypothesis that a “folklore” existed, that is to say a “poetry of the people”, an oral and popular literature. On the other side, you have those that consider that fairytales are inscribed in the history of literature, and that like other objects of literature (be it oral or written), they have intertextual relationships with other texts and other forms of stories. So they hold that fairytales are not “pure, spontaneous emanations”. (And given this is a literary class, given by a literary teacher, to literary students, the teacher did admit their bias for the “literary family” and this was the main focus of the class).

Which notably led us to a third bibliography, this time collecting works that massively changed or influenced the fairytale critics - but this time books that exclusively focused on the works of Perrault and Grimm, and here again we find the same divide folklore VS textuality and intertextuality. It is Marc Soriano’s Les contes de Perrault: culture savante et traditions populaires, it is Ernest Tonnelat’s Les Contes des frères Grimm: étude sur la composition et le style du recueil des Kinder-und-Hausmärchen ; it is Jérémie Benoit’s Les Origines mythologiques des contes de Grimm ; it is Wilhelm Solms’ Die Moral von Grimms Märchen ; it is Dominqiue Leborgne-Peyrache’s Vies et métamorphoses des contes de Grimm ; it is Jens E. Sennewald’ Das Buch, das wir sind: zur Poetik der Kinder und-Hausmärchen ; it is Heinz Rölleke’s Die Märchen der Brüder Grimm: eine Einführung. No English book this time, sorry.

II) The Germans were French, and the French Italians

The actual main topic of this class was to consider the “fairytale” in relationship to the notions of “intertextuality” and “rewrites”. Most notably there was an opening at the very end towards modern rewrites of fairytales, such as Angela Carter’s The Bloody Chamber, “Le petit chaperon vert” (Little Green Riding Hood) or “La princesse qui n’aimait pas les princes” (The princess who didn’t like princes). But the main subject of the class was to see how the “main corpus” of classic fairytales, the Perrault, the Grimm, the Basile and Straparola fairytales, were actually entirely created out of rewrites. Each text was rewriting, or taking back, or answering previous texts - the history of fairytales is one of constant rewrite and intertextuality.

For example, if we take the most major example, the fairytales of the brothers Grimm. What are the sources of the brothers? We could believe, like most people, that they merely collected their tale. This is what they called, especially in the last edition of their book: they claimed to have collected their tales in regions of Germany. It was the intention of the authors, it was their project, and since it was the will and desire of the author, it must be put first. When somebody does a critical edition of a text, one of the main concerns is to find the way the author intended their text to pass on to posterity. So yes, the brothers Grimm claimed that their tales came from the German countryside, and were manifestations of the German folklore.

But... in truth, if we look at the first editions of their book, if we look at the preface of their first editions, we discover very different indications, indications which were checked and studied by several critics, such as Ernest Tomelas. In truth, one of their biggest sources was... Charles Perrault. While today the concept of the “tales of the little peasant house, told by the fireside” is the most prevalent one, in their first edition the brothers Grimm explained that their sources for these tales were not actually old peasant women, far from it: they were ladies, of a certain social standing, they were young women, born of exiled French families (because they were Protestants, and thus after the revocation of the édit de Nantes in France which allowed a peaceful coexistance of Catholics and Protestants, they had to flee to a country more welcoming of their religion, aka Germany). They were young women of the upper society, girls of the nobility, they were educated, they were quite scholarly - in fact, they worked as tutors/teachers and governess/nursemaids for German children. For children of the German nobility to be exact. And these young French women kept alive the memory of the French literature of the previous century - which included the fairytales of Perrault.

So, through these women born of the French emigration, one of the main sources of the Grimm turns out to be Perrault. And in a similar way, Perrault’s fairytales actually have roots and intertextuality with older tales, Italian fairytales. And from these Italian fairytales we can come back to roots into Antiquity itself - we are talking Apuleius, and Virgil before him, and Homer before him, this whole classical, Latin-Greek literature. This entire genealogy has been forgotten for a long time due to the enormous surge, the enormous hype, the enormous fascination for the study of folklore at the end of the 19th century and throughout all of the 20th.

We talk of “types of fairytales”, if we talk of Vladimir Propp, if we talk of Aarne Thompson, we are speaking of the “morphology of fairytales”, a name which comes from the Russian theorician that is Propp. Most people place the beginning of the “structuralism” movement in the 70s, because it is in 1970 that the works of Propp became well-known in France, but again there is a big discrepancy between what people think and what actually is. It is true that starting with the 70s there was a massive wave, during which Germans, Italians and English scholars worked on Propp’s books, but Propp had written his studies much earlier than that, at the beginning of the 20th century. The first edition of his Morphology of fairytales was released in 1928. While it was reprinted and rewriten several times in Russia, it would have to wait for roughly fifty years before actually reaching Western Europe, where it would become the fundamental block of the “structuralist grammar”. This is quite interesting because... when France (and Western Europe as a whole) adopted structuralism, when they started to read fairytales under a morphological and structuralist angle, they had the feeling and belief, they were convinced that they were doing a “modern” criticism of fairytales, a “new” criticism. But in truth... they were just repeating old theories and conceptions, snatched away from the original socio-historical context in which Propp had created them - aka the Soviet Union and a communist regime. People often forget too quickly that contextualizing the texts isn’t only good for the studied works, we must also contextualize the works of critics and the analysis of scholars. Criticism has its own history, and so unlike the common belief, Propp’s Morphology of fairytales isn’t a text of structuralist theoricians from the 70s. It was a text of the Soviet Union, during the Interwar Period.

So the two main questions of this class are. 1) We will do a double exploration to understand the intertextual relationships between fairytales. And 2) We will wonder about the definition of a “fairytale” (or rather of a “conte” as it is called in French) - if the fairytale is indeed a literary genre, then it must have a definition, key elements. And from this poetical point of view, other questions come forward: how does one analyze a fairytale? What does a fairytale mean?

III) Feuding families

Before going further, we will pause to return to a subject talked about above: the great debate among scholars and critics that lasted for decades now, forming the two branches of the fairytale study. One is the “folklorist” branch, the one that most people actually know without realizing it. When one works on fairytale, one does folklorism without knowing it, because we got used to the idea that fairytale are oral products, popular products, that are present everywhere on Earth, we are used to the concept of the universality of motives and structures of fairytales. In the “folklorist” school of thought, there is an universalism, and not only are fairytales present everywhere, but one can identify a common core for them. It can be a categorization of characters, it can be narrative functions, it can be roles in a story, but there is always a structure or a core. As a result, the work of critics who follow this branch is to collect the greatest number of “versions” of a same tale they can find, and compare them to find the smallest common denominator. From this, they will create or reconstruct the “core fairytale”, the “type” or the “source” from which the various variations come from.

Before jumping onto the other family, we will take a brief time to look at the history of the “folklorist branch” of the critic. (Though, to summarize the main differences, the other family of critics basically claims that we do not actually know the origin of these stories, but what we know are rather the texts of these stories, the written archives or the oral records).

So the first family here (that is called “folklorist” for the sake of simplicity, but it is not an official or true appelation) had been extremely influenced by the works of a famous and talented scholar of the early 20th century: Aarne Antti, a scholar of Elsinki who collected a large number of fairytales and produced out of them a classification, a typology based on this theory that there is an “original fairytale type” that existed at the beginning, and from which variants appeared. His work was then continued by two other scholars: Stith Thompson, and Hans-Jörg Uther. This continuation gave birth to the “Aarne-Thompson” classification, a classification and bibliography of folkloric fairytales from around the world, which is very often used in journals and articles studying fairytales. Through them, the idea of “types” of fairytales and “variants” imposed itself in people’s minds, where each tale corresponds to a numbered category, depending on the subjects treated and the ways the story unfolds (for example an entire category of tale collects the “animal-husbands”. This classification imposed itself on the Western way of thinking at the end of the first third of the 20th century.

The next step in the history of this type of fairytale study was Vladimir Propp. With his Morphology of fairytales, we find the same theory, the same principle of classification: one must collect the fairytales from all around the world, and compare them to find the common denominator. Propp thought Aarne-Thompson’s work was interesting, but he did complain about the way their criteria mixed heterogenous elements, or how the duo doubled criterias that could be unified into one. Propp noted that, by the Aarne-Thompson system, a same tale could have two different numbers - he concluded that one shouldn’t classify tales by their subject or motif. He claimed that dividing the fairytales by “types” was actually impossible, that this whole theory was more of a fiction than an actual reality. So, he proposed an alternate way of doing things, by not relying on the motifs of fairytales: Propp rather relied on their structure. Propp doesn’t deny the existence of fairytales, he doesn’t put in question the categorization of fairytales, or the universality of fairytales, on all that he joins Aarne-Thompson. But what he does is change the typology, basing it on “functions”: for him, the constituve parts of fairytales are “functions”, which exist in limited numbers and follow each other per determined orders (even if they are not all “activated”). He identified 31 functions, that can be grouped into three groups forming the canonical schema of the fairytale according to Propp. These three groups are an initial situation with seven functions, followed by a first sequence going from the misdeed (a bad action, a misfortune, a lack) to its reparation, and finally there is a second sequence which goes from the return of the hero to its reward. From these seven “preparatory functions”, forming the initial situation, Propp identified seven character profiles, defined by their functions in the narrative and not by their unique characteristics. These seven profiles are the Aggressor (the villain), the Donor (or provider), the Auxiliary (or adjuvant), the Princess, the Princess’ Father, the Mandator, the Hero, and the False Hero. This system will be taken back and turned into a system by Greimas, with the notion of “actants”: Greimas will create three divisions, between the subject and the object, between the giver and the gifted, and between the adjuvant and the opposant.

With his work, Vladimir Propp had identified the “structure of the tale”, according to his own work, hence the name of the movement that Propp inspired: structuralism. A structure and a morphology - but Propp did mention in his texts that said morphology could only be applied to fairytales taken from the folklore (that is to say, fairytales collected through oral means), and did not work at all for literary fairytales (such as those of Perrault). And indeed, while this method of study is interesting for folkloric fairytales, it becomes disappointing with literary fairytales - and it works even less for novels. Because, trying to find the smallest denominator between works is actually the opposite of literary criticism, where what is interesting is the difference between various authors. It is interesting to note what is common, indeed, but it is even more interesting to note the singularities and differences. Anyway, the apparition of the structuralist study of fairytales caused a true schism among the field of literary critics, between those that believe all tales must be treated on a same way, with the same tools (such as those of Propp), and those that are not satisfied with this “universalisation” that places everything on the same level.

This second branch is the second family we will be talking about: those that are more interested by the singularity of each tale, than by their common denominators and shared structures. This second branch of analysis is mostly illustrated today by the works of Ute Heidmann, a German/Swiss researcher who published alongside Jean Michel Adam (a specialist of linguistic, stylistic and speech-analysis) a fundamental work in French: Textualité et intertextualité des contes: Perrault, Apulée, La Fontaine, Lhéritier... (Textuality and intertextuality of fairytales). A lot of this class was inspired by Heidmann and Adam’s work, which was released in 2010. Now, this book is actually surrounded by various articles posted before and after, and Ute Heidmann also directed a collective about the intertextuality of the brothers Grimm fairytales. Heidmann did not invent on her own the theories of textuality and intertextuality - she relies on older researches, such as those of the Ernest Tonnelat, who in 1912 published a study of the brothers Grimm fairytales focusing on the first edition of their book and its preface. This was where the Grimm named the sources of their fairytales: girls of the upper class, not at all small peasants, descendants of the protestant (huguenots) noblemen of France who fled to Germany. Tonnelat managed to reconstruct, through these sources, the various element that the Grimm took from Perrault’s fairytales. This work actually weakened the folklorist school of thought, because for the “folklorist critics”, when a similarity is noted between two fairytales, it is a proof of “an universal fairytale type”, an original fairytale that must be reconstructed. But what Tonnelat and other “intertextuality critics” pushed forward was rather the idea that “If the story of the Grimm is similar but not identical to the one of Perrault, it is because they heard a modified version of Perrault’s tale, a version modified either by the Grimms or by the woman that told them the tale, who tried to make the story more or less horrible depending on the situation”. This all fragilized the idea of an “original, source-fairytale”, and encouraged other researchers to dig this way.

For example, the case was taken up by Heinz Rölleke, in 1985: he systematized the study of the sources of the Grimm, especially the sources that tied them to the fairytales of Perrault. Now, all the works of this branch of critics does not try to deny or reject the existence of fairytales all over the world. And it does not forget that all over the world, human people are similar and have the same preoccupations (life, love, death, war, peace). So, of course, there is an universality of the themes, of the motives, of the intentions of the texts. Because they are human texts, so there is an universality of human fiction. But there is here the rejection of a topic, a theory, a question that can actually become VERY dangerous. (For example, in post World War II Germany, all researches about fairytales were forbidden, because during their reign the Nazis had turned the fairytales the Grimm into an abject ideological tool). This other family, vein, branch of critics, rather focuses on the specificity of each writing style, of each rewrite of a fairytale, but also on the various receptions and interpretations of fairytales depending on the context of their writing and the context of their reading. So the idea behind this “intertextuality study” is to study the fairytales like the rest of literature, be it oral or written, and to analyze them with the same philological tools used by history studies, by sociology study, by speech analysis and narrative analysis - all of that to understand what were the conditions of creation, of publication, of reading and spreading of these tales, and how they impacted culture.

#fairy tales#fairytales#fairytale#fairy tale#a class on fairytales#brothers grimm#grimm fairytales#charles perrault#perrault fairytales#history of fairytales#vladimir propp#aarne-thompson classification#aarne-thompson#analysis of fairytales#critics of fairytales#book reference#sources#fairytale research#literary vs folklorist#which actually should be more intertextuality vs folklorist

103 notes

·

View notes

Note

I hate the rampant fetishization of Pocahontas so much. Do people not understand that she was a real Native person? The Disney movie was such a disgustingly racist mistake.

I think theres a large variants of how much people know about her. A lot of people know she was a real person, but believe the myth that she and John Smith had a "romance" (which was perpetuated long before Disney, Disney just added gasoline to the flames). Id say a LOT of people probably know the White (& whitewashed) version of her story. A lot of people know she was a real historical figure & that she was an important figure, but not much else. Some people don't know she was real at all & think she was just a cartoon character. Some people know her real history & everything but don't care & continue to fetishize her bc of racism & racial fetishization of Native women.

The people who know the history of what ACTUALLY happened via Powhatan oral history is in the minority, & it's either unknown or overlooked as "inaccurate" because it is oral history (even though we know John Smith was even known for being a liar & used the story of an "exotic" princess in a foreign country falling in love with him & saving him from her father at least THREE other times before Matoaka.) I know there's also misinformation variants going around of the oral history version of tiktok, in which people are saying she married John Smith at age 12, which of course is false: she MET John Smith at age 10-12, and she married John ROLFE after age 17.

I know the Disney company even consulted some Powhatan oral history but they just chose not to use most of it in favor of the myths surrounding her. You can tell because they use the plotlines of her recieving a necklace, associating her with water (which is found in her name), having her mother be dead, and adding Kocoum. It really was a mistake

36 notes

·

View notes

Text

APPALACHIAN FOLKLORE 101

Appalachia has a rich history in the united states, which goes farther back than most tend to give it credit for. The Appalachian mountains are millions of years old, and humans have only lived in the region for 16,000 years or so, which means the mountains are bound to hold some mysteries and legends.

Many of these stories, and folk practices originate from the Native Americans, specifically Cherokee, and are mixed in with the superstitions brought over from the old world specifically English, Irish, and Scottish. As well as the practices brought over from the African Continent During the Slave Trade.

The Native population assisted the early settlers in Appalachia with ways to survive the area, grow food, and even forage for one of Appalachia's staple foods, RAMPS!!!

Let's delve into the history of Appalachian Folklore and the origins of everyone's favorite stories.

Cryptids and Myths

This is one of the most famous aspects of Appalachian folklore and one which outsiders know the most about, Appalachian Myths and their Cryptids that follow. Below I will go over a few of the more famous ones, which many have learned about, either second-hand or through living in the area.

The Moon-Eyed People

There was a group of humanoids called the Moon-Eyed People, who were short, bearded, and had pale skin with large, bright eyes. They were completely nocturnal due to their eyes being extremely sensitive to light. Although not mythical, they were considered a separate race of people by some. The tribes viewed them as a threat and forced them out of their caves on a full moon night. They were said to have scattered to other parts of Appalachia as the moon’s light was too bright for their eyes. There are some early structures that are believed to be related to the Moon-Eyed People, dating back to 400 BCE. Some theories suggest that they were early European settlers who arrived much before Columbus discovered the Americas. Other theories suggest they were people who had Albanism.

Image of The Moon Eyed People Statues in Murphy, North Carolina

Spearfinger

Spearfinger is a Cherokee legend of a shapeshifting, stone-skinned witch with a long knife in place of one of her fingers. She often was described as an old woman, which she would take the form of to convince Cherokee children that she was their grandmother. She would sit with them, brush their hair until they fell asleep, and then kill them with her “spear finger.” She had a love of human livers which she would extract from the bodies of those she killed. It was said she left no visible scars on her victims. She carried her own heart in her hand to protect it, as it was her one weakness. As the legend goes, she was captured and defeated with the help of several birds that carried the information to defeat her. Though she has been destroyed, sometimes you can hear her cackles and songs throughout the mountains.

Image of SpearFinger Cherokee Legend

W*ndigo

This spirit is said to go to where its name is called allowed so since most of us already know the name I won't be writing it out in completion. So out of respect for some of our native readers, it will remain censored

The W*ndigo is a creature, sometimes referred to as an evil spirit, that is said to be 15 feet tall with a body that is thin, with skin pulled so tight that its bones are visible. Many native legends view it as a spirit of greed, gluttony, and insatiable hunger. It is a flesh-eating beast that is considered most active during the colder months, and its presence is easily felt and smelt. It has been described as having a distinct smell of rot and decay due to its skin being ripped and unclean. It produces an overwhelming urge of greed and insatiable want. Most notably, it is not one to chase or seek after its prey; instead, it uses its terrifying mimicry skill. It often mimics human voices, screams, loved ones, or anything that might entice its victim to come to it. In some cases, it is believed the W*ndigo is a spirit that can possess other humans and fill them with greed and selfishness, turning them into W*ndigos as well.

Appalachian Folk Practices

Many of the common Appalachian folk practices stem from things the Native Americans and Enslaved Africans taught them mixed in with cultural practices from Europe. Here I will go over some of the most common practices done by the Appalachian people

Water Dowsing

water dowsing is a practice that has been done for hundreds of years in many different cultures. This practice was brought over by the European settlers and was how many people of the time found where to dig for their water. The practice itself is simple in nature, you take a forked branch from a tree and hold it in both hands and walk around once the stick points down due to the electromagnetic current that's where you dig your well.

this isn't exactly the best way to find water but many people still do it to this day.

Image of Someone Using A Dowsing Rod

Bottle Trees

This practice originated in the Congo area of Africa, in the 9th century A.D. brought to America by the slave trade, in the 17th century. Bottle Trees, were popular in the American South and up into Appalachia, the spirits are said to be attracted to the blue color of the bottles, and captured at night, then when the sun rises it destroys the evil spirits.

This is still practiced in the modern era by many Appalachian Folk Practitioners

Image Of Bottle Trees

SIN EATING

This practice originates from the Ancient Greeks and Egyptians, it branched to many different cultures and has been practiced since antiquity by many Christian and Catholic tribes. And later making its way to America via immigration. The process was once a profession in Appalachia, in which food was placed on or near the deceased and a person dressed in all black would eat the food absolving the dead of all of their earthly sins. This essentially cemented their ability to get into heaven. The practice while sparsely done any more as a profession, it can still be found in many peoples funeral services to this day around the world.

Many cultures still do this practice and the sin eaters usually choose to hide their identity as the practice is seen as taboo to this day.

Popular Herbs To Forage In Appalachia Folk Practices

Wild Leeks or RAMPS!!!

Allium tricoccum, are a species of wild onion native to North America. They are a delicacy, and hold a special place in the hearts of many Appalachians. Native Americans such as the Cherokee ate the plant and used it medicinally for a variety of purposes including as a spring tonic. Early European settlers learned how to Forage from the Indigenous People and continued to eat and use ramps medicinally. Ramps provide many nutrients and minerals and historically have been used to nourish people after harsh winters.

*RAMPS poisoness Look Alike

False hellebore (Veratrum) is a highly poisonous plant that can be mistaken for a prized wild edible, the wild leek, or ramp (Allium tricoccum)

Chicken of the Woods

Laetiporus sulphureus. Chicken of the woods is a sulphur-yellow bracket fungus of trees in woods, parks and gardens. They are delicious and are loved by many foragers, Native Americans, and Appalachians alike. The Native Americans taught the early settlers that these were edible and have been a favorite ever since. Chicken of the Woods is most likely to be found from August through October, but it can be found as early as May and up to December depending on where you live.

*These have a poisoness look alike, Jack O Lantern mushrooms

The Jack-o'-lantern mushroom should not be eaten because it is poisonous to humans. It contains toxic chemicals that can cause severe stomach upset accompanied by vomiting, diarrhea and headache

PawPaws

The Pawpaw Asimina triloba, is well loved by Appalachian locals as a native fruit with a tropical taste. Pawpaw fruit is the largest tree fruit native to the United States, and its custard-like flesh has been said to taste like a combination of banana, pineapple, and Mango. The pawpaw has been used by Native Americans for centuries for both its fruit and its medicinal properties. Many tribes, including the Osage and Sioux, ate the fruit; the Iroquois used the mashed fruit to make small dried cakes to reconstitute later for cooking. PawPaw season is late summer, look for the smell of rotting fruit, eat the ones that are squishy to the touch.

*They resemble mangos on the trees, many options to eat the ones that are on the floor already as they usually have ripened, but you can also ripen them at home.

Appalachia has a rich and beautiful history filled with magic and delicious food. But the only real way to learn about Appalachia is to visit it. Go and speak with locals, learn about the history, their delicious foods, and powerful Grandma magic, and you too will fall in love with Appalachia.

Thank you for sitting down and having Tea with me on the Other side of the Great Divide

#witchcraft#ritual#occultism#esoteric#occult#spirit work#magi#magus#magick#witch#witchy vibes#witches#witch tips#appalachian folk magic#appalachia#appalachain mountains#american folklore#folklore#folklorist#appalachian culture#foraging#WanderingSorcerer

602 notes

·

View notes

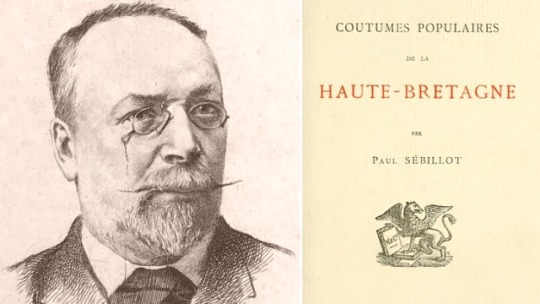

Photo

23 avril 1918 : mort du folkloriste, peintre et écrivain Paul Sébillot ➽ http://bit.ly/Paul-Sebillot Fondateur de la « Société des traditions populaires » et de la « Revue des traditions populaires », il était, de son vivant déjà, considéré comme le premier folkloriste de France, et son oeuvre est empreinte d’une clarté, d’une simplicité, d’une érudition élégamment dissimulée malgré la précision consciencieuse du détail

#CeJourLà#23Avril#Sébillot#folkloriste#folklore#traditions#populaires#érudit#écrivain#biographie#histoire#france#history#passé#past#français#french#news#événement#newsfromthepast

12 notes

·

View notes

Text

As we're moving away from the dark seasons, in the period where spring is only just preparing for its first steps, I created this journal entry on the Krampus and the Perchten, famous Alpine winter spirits.

It's a compilation of text excerpts from scientific articles and printed photos/stickers, arranged in a way that reminds me of zines. I've always wanted to create zines on folklore, cryptozoology, mysteries and similar topics so maybe it does happen someday 😁.

#folklorist#folkhorror#folklore#bujo#bujo spread#commonplace journal#commonplace book#commonplacing#dark#commonplace#journaling#journal#bullet journal#krampus#perchten#winter#bujo community

227 notes

·

View notes

Note

Would you say that RWBY breaks apart the concept of the Hero's Journey?

the monomyth is an ethnocentric horoscope and joseph campbell is a HACK

there is not a single myth in history, from any time or culture prior to the popularization of campbell’s work in the late seventies, that follows his “hero’s journey” and his claim that it is a universal narrative is predicated on the plainly ridiculous assertion that all myths that kinda, sorta, vaguely resemble the model still count even if they don’t actually traverse all or even most of its seventeen stages. and he entirely ignores myth and folklore that do not even notionally resemble his model, of which there is a multitude. typically reductive jungian bullshit.

a story can follow the hero’s journey, certainly. star wars made it wildly popular with the general american public and it has infested writerly circles as one of the ubiquitous narrative structures stories are “”supposed“” to follow so yes there is an abundance of monomythic stories written in the last half a century or so and within that timeframe it is not a wholly worthless analytical device (not because the model is true but because it’s popular)—but i don’t think it’s possible to deconstruct, really, any more than a story with complex characters could be called a deconstruction of astrology or MBTI typing. you could actively set out to write a story of mythic scope that pointedly does not traverse even a single stage of the hero’s journey and people who do jungian analysis would still retrofit it to the monomyth.

fucking alice’s adventures in wonderland has been retrofitted to the monomyth. and i mean, people are fucking weird about alice in wonderland across the board, but when a model that sells itself as The Universal Myth is being applied uncritically to the best-known piece of nonsense literature in the world there’s not really a question of its legitimacy anymore; people who buy into the monomyth will see it in every story. because it is a horoscope.

as far as rwby goes, my sense is that the writing team knows their stuff on actual myth and folklore far too well to inflict the monomyth on any of it: among other things that is what gives ‘the lost fable’ its mythical verisimilitude. atlas is atlantis ruled by a king who sees himself as atlas telamon but is in reality nothing more than a man, doomed by his moral decay, and vale is fucking athens and ozpin is plato holding up his atlantis to illustrate the virtues he wants to teach. the god who made it a paradise departs when its avarice and cruelty becomes intolerable and the city falls into the sea. like. rwby is not shallow in its intertextuality. the ozian allusion is a detailed retelling of ‘the marvelous land of oz.’ the journey through wonderland was specific and meticulous in its use of the carroll books and pop cultural deviations thereof to articulate its own themes. insofar as rwby could be said to deconstruct the monomyth it’s through loving engagement with real myth, both new and old.

41 notes

·

View notes

Text

jstor search filters group folklore journals under anthropology. which makes sense to me but that academic advisor told me folklore isn't anthropology so now as i'm trying to dig up sources abt the link between the two to make my case i'm not able to filter efficiently for "pure" anthropology journals & i am afraid i will get caught in an infinite loop of using articles from folklore journals and being told it's not anthropology

#soapbox#folklorists are usually considered anthropologists too i don't see the issue...#like there are ways you could analyze folklore where it would slot more into literature or art history#but my ideas are much more in the vein of anthropology so#idk i mean i'm arguing with an archaeologist over whether folklore studies count as sociocultural anthropology this may be a lost cause

17 notes

·

View notes