#food history

Text

How to cook in a medieval setting

Alright. As some of the people, who follow me for a longer while know... I do have opinions about cooking in historical settings. For everyone else a bit of backstory: When I was still LARPing, I would usually come to LARP as a camp cook, making somewhat historically accurate food and selling it for ingame coin. As such I know a bit about how to cook with a historical set up. And given I am getting so much into DnD and DnD stories right now, let me share a bit for those who might be interested (for example for stories and such).

🍲Cooking at Home

First things first: For the longest time in history most people did not have actual kitchens. Because actual kitchens were rather rare. Most people cooked their food over their one fireplace at home, which looked something like what you see above. There was something made of metal hanging over the fireplace. At times this was on hinges and movable, at times it was set in place. You could hang pots and kettles over it. When it came to pans, people either had a mount they would put over the fire or some kind of grid they could easily put into place there with some sourts of mounts (like the two metal thingies you can see above).

If you have a modern kitchen, you are obviously used to cook on several cooktops (for most people it is probably four of them), while in this historical you obviously only had one fire. Of course, as you can also see in the picture above, you could often put two smaller pots over the flames or put in a pan onto the fire additionally. But yes, the way we cook in modern times is very different.

Because of this a lot of people often ate stews and soups of sort. You could make those in just one pot - and often could eat from the same stew for days. In a lot of taverns the people had an "everything stew" going, which worked on the idea that everyone just brought their food leftovers, which were all put into one pot everyone would eat from.

Now, some alert readers might have also noticed something: What about bread and pastries? If you only have one fireplace and no oven, how did people make bread?

Well, there were usually three different methods for this. The most common one was communal ovens. Often people had one communal oven in a neighborhood. Especially in a village there might just be a communal oven everyone would just put their bread in to bake. (Though often this oven would only be fired up once or twice a week.)

The second version to deal with this some people used was a sort of what we today call a dutch oven. A pot made either of metal or clay with a lit you would put into the hot coals and then put bread or pastries into that, baking it like that.

There was also a version where people just baked bread in pans on the fire, rotating the bread during the baking process. At least some written accounts we have seem to imply. (Never tried this method, though. I have no idea how this might work. My camp bread was mostly done in dutch ovens or as stickbread.)

Keep in mind that the fireplace at home was very important for the people in historical times. Because it was their one source of warmth in the house.

🏕️ Cooking at Camp

Technically speaking cooking at camp is not that different - with the exception of course that you have to drag all your supplies along. And while in Baldur's Gate 3 and most other videogames you can carry around several sets of full-plate armor and several pounds of ingredients so that dear Gale can whip something up... In real life as an adventurer running around you need to make decisions on what to take along.

If you have read Lord of the Rings, you might remember how many people have criticized Sam for actually dragging all his cooking supplies along and how sad he was for not being able to cook for most of the time, because they were very limited in taking ingredients along.

So, yes, if you are an adventurer who is camping out in the open, you will probably need to do a lot of hunting and gathering to eat during your travels. You can take food for a couple of days along, but not for a lot.

A special challenge is of course, that while you can cook food for several days when you are at homes, you do not want to drag along a prepared stew for several days. So usually you will cook in smaller batches.

A lot of people who were journeying would often just take along one or two pots along.

So, what would you eat as an adventurer travelling around while trying to save the world from some evil forces? Well, it would depend on the time of the year of course. You would probably hunt yourself some food. For example hares, birds or squirrels. Mostly small things you can eat within one or two days. You do not want to drag along half a dead deer. In the warm months you might also forrage for all sorts of greens. You also can cook with many sorts of roots. Of course you can also always look into berries and other fruits you might find.

Things you might bring with you might be salt and some spices. A good thing to bring along would be herbs for tea, too, because I can tell you from experience that water you might have gotten from a river does not always taste very well - and springs with fresh water are often not accessible.

Now, other than what you can access the basic ideas of camping fires and cooking with them has not changed in the last few thousand years. While modern people camping usually have a car nearby and hence will have access to a lot of ingredients. But the general ideas of how to build a fire and put a pot over it... has not really changed.

So, yeah.

Just keep in mind that for the most part in historical settings until fairly recently, there was not much terms of proper kitchens. People cooked over an open fire and hence had to get at times ingenius about it.

#dungeons & dragons#baldurs gate 3#lord of the rings#medieval europe#medieval#cooking#medieval cooking#food history#historical settings#history#european history#writing#fantasy#writing resources

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Want to see a cool research thing? It's a collection of digitized menus from the 1800/1900s at the New York Public Library.

Perfect for my historical fiction peeps or culinary historians

301 notes

·

View notes

Text

Why We Can't Have Medieval Food

I noted in a previous post that I'd "expand on my thinking on efforts to reproduce period food and how we’re just never going to know if we have it right or not." Well, now I have 2am sleep?-never-heard-of-it insomnia, so let's go.

At the fundamental level, this is the idea that you can't step in the same river twice. You can put your foot down at the same point in space, and it'll go into water, but that's different water, and the bed of the river has inevitably changed, even a little, from the last time you did so.

Our ingredients have changed. This is not just because we can't get the fat from fat-tailed sheep in Ireland, or silphium at all anywhere, although both of those are true. But the aubergine you buy today is markedly different to the aubergine that was available even 40 years ago. You no longer need to salt aubergine slices and draw out the bitter fluids, which was necessary for pretty much all of the thing's existence before (except in those cultures that liked the bitter taste). The bitterness has been bred out of them. And the old bitter aubergine is gone. Possibly there are a few plants of it preserved in some archive garden, or a seed bank, or something, but I can't get to those.

We don't really have a good idea of the plant called worts in medieval English recipes. I mean, we know (or we're fairly sure) it was brassica oleracea. But that one species has cultivars as distinct as cabbage, broccoli, cauliflower, kale, Brussels sprouts, collard greens, Savoy cabbage, kohlrabi, and gai lan (list swiped from Wikipedia). And even within "cabbage" or "kale", you have literally dozens of varieties. If you plant the seeds from a brassica, unless you've been moderately careful with pollination, you won't get the same plant as the seeds are from. You can crossbreed brassicas just by planting them near each other and letting them flower. And of course there is no way to determine what varietal any medieval village had, a very high likelihood that it was different to the village next door, and an exceedingly high chance that that varietal no longer exists. Further, it only ever existed for a few tens of years - before it went on cross-breeding into something different. So our access to medieval worts (or indeed, cabbage, kale, etc) is just non-existant.

Some other species within the brassica genus are as varied. Brassica rapa includes oilseed rape, field mustard, turnip, Chinese cabbage, and pak choi.

We have an off-chance, as it happens, of getting almost the same kind of apple as some medieval varieties, because apples can only be reproduced for orchard use by grafting, which is essentially cloning. Identification through paintings, DNA analysis, and archaeobotany sometimes let us pin down exactly which apple was there. But the conditions under which we grow those apples are probably not the same as the medieval orchard. Were they thinned? When were they harvested? How were they stored? And apples are pretty much the best case.

Medieval wheat was practically a different plant. It was far pickier about where it would grow, and frequently produced 2-4 grains per stalk. A really good year had 6-8. In modern conditions, any wheat variety with less than 30 grains per stalk would be considered a flop.

Meats are worse. Selective breeding in the last century has absolutely and completely changed every single species of livestock, and if you follow that back another five centuries, some of them would be almost unrecognisable. Even our heritage breeds are mostly only about 200 years old.

Cheese, well. Cheese is dependent on very specific bacteria, and there are plenty of conditions where the resulting cheese is different depending on whether it was stored at the back or front of the cave. Yogurts, quarks, skyrs, etc, are also live cultures, and almost certainly vary massively. (I have a theory about British cheese here, too, which I'll expand on in a future post)

So, even before you go near the different cooking conditions (wood, burnables like camel and cow dung, smoke, the material and condition of cooking pots), we just can't say with any reliability that the food we're making now is anything like medieval people produced from the same recipe. We can't even say that with much reliability over a century.

Under very controlled conditions, you could make an argument for very specific dishes. If you track down a wild mountain sheep in Afghanistan, and use water from a local spring, and salt from some local salt mine, then you can make a case that you can produce something fairly close to the original ma wa milh, the water-and-salt stew that forms the most basic dish in Arabic cookery. But once you start introducing domestic livestock, vegetables, or even water from newer wells, you're now adrift.

It is possible that some dishes taste exactly the same, by coincidence. But we can't determine that. We can't compare the taste of a dish from five years ago, let alone five hundred, because we're only just getting to a state where we can "record" a taste accurately. Otherwise it's memory and chance.

We've got to be at peace with this. We can put in the best efforts we can, and produce things that are, in spirit, like the medieval dishes we're reading about. But that's as good as it gets.

#medieval cookery#medieval cooking#food history#historical cookery#historical cuisine#medieval arabic cookery#horticulture#genetics

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

For living ye olde lifestyle: To the King's Taste, Richard II's book of feasts and recipes adapted for modern cooking, Lorna J Sass, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1975. Most recipes are taken from the fourteenth-century Forme of Cury and include "a Brie and egg tart, a fruit and salmon pie, parsnip fritters, an elderflower cheesecake, stuffed loaves, spiced wine, rose hips in wine with almonds."

#cookbook#medieval#Lorna J Sass#food#SCA#food history#Lorna Sass#To the King's Taste#Richard II#14th century#Forme of Cury#medieval literature

201 notes

·

View notes

Text

This makes Tiana the Princess of Creole Cuisine!

🍽️👩🏾🦱👑

#history#princess tiana#disney#princess and the frog#leah chase#animated history#disney princess#new orleans#food#movie#historical figures#creole#american history#united states#disney world#black girl magic#african american women#food history#soft black women#soft girl#women empowerment#black history#girl power#womens history#dooky chase#black femininity#princesscore#historical women#nickys facts

154 notes

·

View notes

Text

My Favorite Historical List

Foodstuffs in American invented to curb sexual desire.

Graham crackers: a cookie to avoid your cookie. Sylvester Graham believed that “carnal desire” caused headaches, epilepsy, and insanity. He invented something very impressively bland and stale, believing the harder your teeth throb the harder other parts of you won’t. Obviously, to this day we eat them in the woods at night to keep Bigfoot away 😏.

Granula/Granola: Originally created by James Caleb Jackson in the ongoing war against the horniest meal of the day, breakfast. Author of other such publications as Dancing: Its Evils and Its Benefits and

American Womanhood: Its Peculiarities and Necessities. Like the others, he was a staunch vegetarian that believed just as dust to dust, consuming meat lead to consuming meat.

Corn Flakes: the classic wet breakfast to get you dry, created by John Harvey Kellogg. You know him, you’re concerned about him, this haunted son of a gun employed a high-powered enema machine daily that could shoot fifteen gallons of water up into his christian hole as God intended. Kellogg also improved upon granula, adding the O in there so he could remove the O in others, amen.

#jokes#lists#history#food history#John Harvey Kellogg is in hell experiencing one of the most interesting damnations probably

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

2024 Reading Log, pt 2

006. Gardening Can Be Murder by Marta McDowell. I honestly thought that this book was going to be about something else. With the subtitle “how poisonous plants, sinister shovels and grim gardens have inspired mystery writers”, I thought it was going to be about, you know, that. True crime themed to gardens, discussions of poisonous plants, that sort of thing. The book is actually about the mystery books that have gardening as a theme. And while the author’s dedication to not spoiling anything (seriously, anything, even 150 year old stories like The Moonstone or “Rappacini’s Daughter”) is admirable in its own way, this leaves the book feeling like endless buildup without any payoff. Big fans of murder mysteries might enjoy this—especially the last chapter, which interviews writers about their gardens—but I found it more boring than anything else, and finished it only because it was very short.

007. Antimony, Gold and Jupiter’s Wolf by Peter Wothers. This book is about how the elements got their names, and most of it deals with the early modern period, as alchemy transitioned to chemistry and then into the 19th century, when chemistry was a real science, but things like atomic theory were not yet understood. The book goes into fascinating detail, and has a lot of quotes from primary sources, as scientists then were just like scientists now, that is, opinionated and bickering with each other over their preferred explanations. And names! Many of the splits between elements and their symbols (like Na for sodium) are due to compromise attempts to appease two different factions with their preferred names. A book covering arcane minutia of history always has the risk of feeling like a slog, but this is a fast and fun read.

008. Doctor Dhrolin’s Dictionary of Dinosaurs by Nathan T Barling and Michael O’Sullivan, illustrations by Mark P Witton. This book is an odd concept, but one that I was immediately on board with—a D&D book written by paleontologists with the intention of bringing accurate and interesting stats for prehistoric reptiles to the game. The fact that it’s mostly illustrated by Mark Witton definitely clinched my backing that Kickstarter. And this book is a lot of fun. So much so, that I read it all in a single sitting. I don’t know how accurate the stats are (like, a Hatzegopteryx has a higher CR than titanosaurs or T. rexes), but they seem like they’d be fun in play, and the writing does a good job of combining fantasy fun with actual education. Even for someone not running a 5e game, the stuff on how to run animals as not killing machines, and the mutation tables, could be useful. There are multiple types of playable dinosaurs, all of which seem like they’d work well at the table and avoid typical stereotypes, and a lot of in-jokes and pop culture references (like the cursed staff of unspared expense, which looks like Hammond’s cane in the Jurassic Park movie).

009. Romaine Wasn’t Built in a Day by Judith Tschann. I’m a sucker for books about etymology. And this one, on food etymology, is a pretty breezy read. I had fun with it, and it even busted some misconceptions that I had, etymologically speaking. Like, there’s no evidence that “bloody” as an explicative originated from “God’s blood”? Wild. Etymology books tend to be written in a sort of stream-of-consciousness style, where talking about one word may lead down a garden path to the next one. The book also has a couple of little matching quizzes, which is something I haven’t seen in a book since like the 90s.

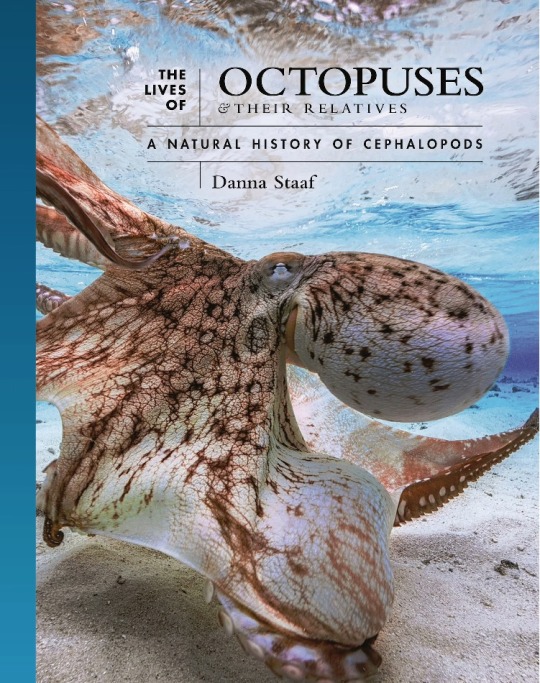

010. The Lives of Octopuses and their Relatives by Danna Staaf. I was previously a little disappointed in The Lives of Beetles, another book in this series, but I knew I liked Staaf, who wrote the excellent book Squid Empire about cephalopod evolution and paleontology. I’m pleased to report that this book is also excellent. Staaf takes the “lives” part seriously, and the book is arranged by ecology, looking at different marine habitats, the challenges that they pose to living things, and the cephalopods that live there. Cuttlefish get slightly short shrift in this book compared to squids and octopuses, but that’s about the biggest complaint I had. I like how the species profiles cover more obscure taxa, and information about the best studied (like Pacific giant octopus and Humboldt squid) is kept to the chapters.

#reading log#marine biology#cephalopods#etymology#food history#tabletop rpgs#dinosaurs#D&D 5e#chemistry#periodic table#history of science#mystery#horticulture

73 notes

·

View notes

Text

Galets are the most typical pasta from Catalonia and the Balearic Islands, together with fideus (short noodles).

Galets can be made in different sizes, from the size of a thumb nail to as big as an open mouth, but the bigger sizes are usually reserved for festivity meals like Christmas soup.

It's unknown when galets were created, but it's known that the profession of pasta maker or noodle maker (fideuer) is centuries-old in Catalonia. In Barcelona, the pasta/noodle makers grouped themselves in a guild in the year 1611.

#menjar#galets#sopa de galets#food#soup#pasta#foodblr#foodie#food photography#food history#history#1600s#eat#savory#savoury#yummy#delicious#meal#cozy#cooking#tasty

96 notes

·

View notes

Text

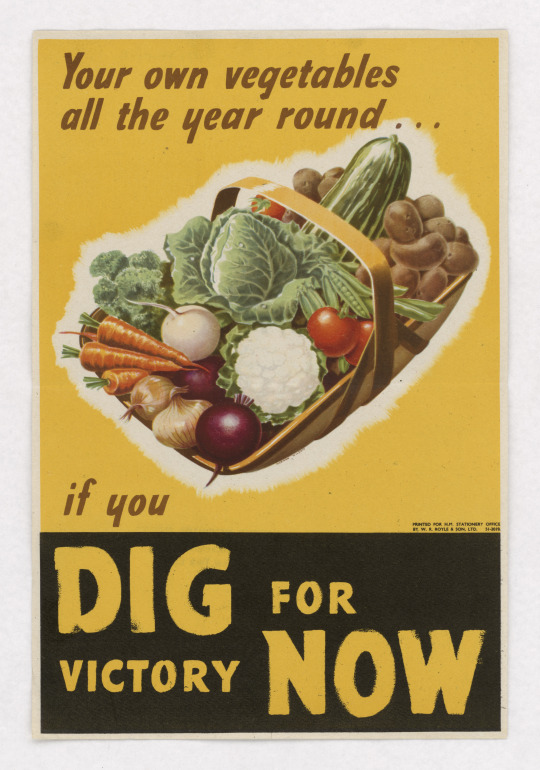

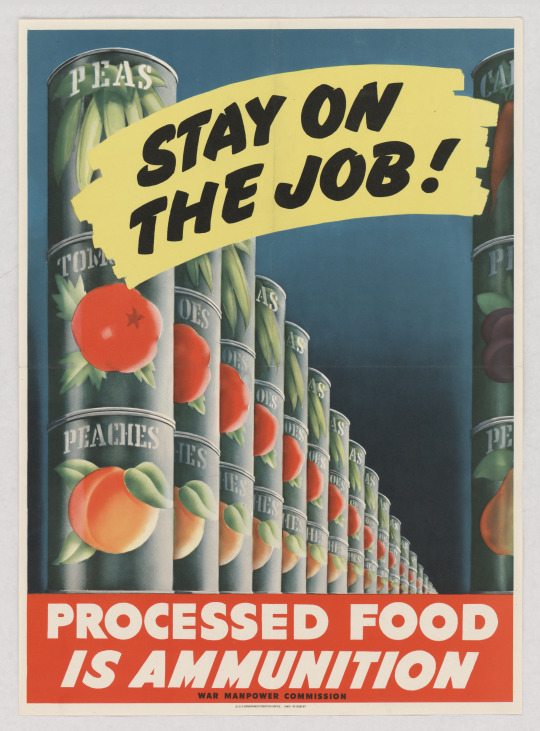

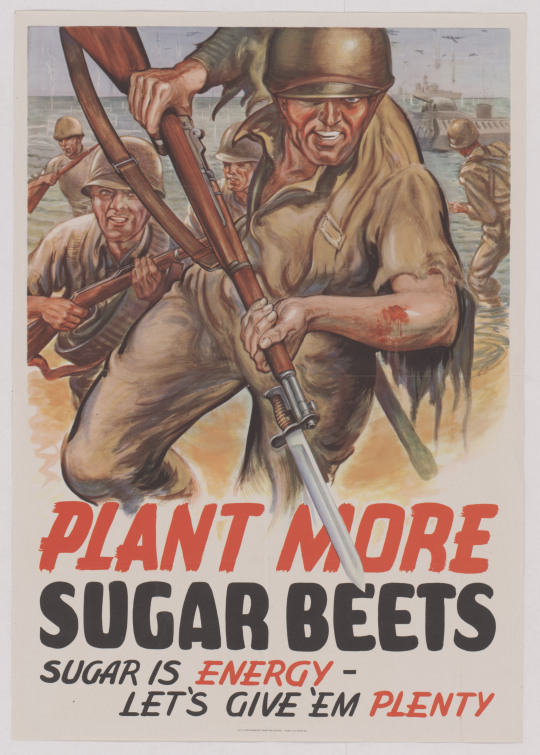

Food Propaganda Posters: From War-Time Rations to Post-War Indulgences 🍔🥩🥧

Food propaganda posters of World Wars I and II rallied the public around wartime efforts, such as home gardening and rationing. But did they shape our post-war diets? Let's explore.

Garden-to-Freezer Revolution 🍡

Victory Gardens, immortalized in posters like these, epitomized wartime self-sufficiency. The advent of post-war technology led to a surge in frozen foods, replacing these gardens with ads for TV dinners.

Meat-Centered Diet 🥩🍖

Wartime posters urged citizens to explore meat alternatives. Post-war advances in farming made meat more accessible and led to a meat-centered diet.

Tin Culture 🍱

Canning, vital during the wars for preserving homegrown produce, transformed into a culture of pre-packaged canned foods.

Sugar Surge 🍨🍭🍬

Rationing sugar was a wartime staple, but in the 1950s, sugary foods and drinks exploded onto the scene, illustrated by soda pop advertisements.

While food propaganda posters influenced wartime diets, the post-war era saw a drastic shift towards convenience and indulgence, as mirrored in the advertising of the time.

What can you discover in our Catalog?

#national archives#history#archives#records#war posters#propaganda#propaganda posters#food#food history#food posters

199 notes

·

View notes

Text

Try to learn about the old foods

I have most recently started to meal prep, with making a lot of foods and putting them in the freezer. This ended up allowing me to buy the foods in bulk from the local market. And, well... This allowed me to eat some of the foods that the supermarket does not have.

We do have a bit of a problem. And that problem mostly is that we got our food kinda messed up. Because people have lost the connection to the food they eat. But also because of colonialism.

The big thing that happened is, that we lost contact with most local foods. No matter where I go in the "first world nations"... The foods offered to me in the supermarkets are the same - and they also look the same.

This means that a lot of people have no real idea, what foods came from where in the world - but also do not know half of the foods that originated with where they are from, because they are not easily available.

Tomatoes are an example. Not only did historical tomatoes look and taste very differently from the tomatoes we eat today, but obviously... they came from the Americas. So they are not a food that originated with Europe and was not widely available in Europe until the 1600s. While, yes, the first tomates came here more than a hundred years earlier... it took a while for them to catch on.

This is parsnip. Another root vegetable that was commonly eaten in Europe for most of history. It has a more intensive taste than the usual carrot - but is also not that different from it, when it comes to consistency and how it is going to cook.

This is fennel. You might know fennel seeds as a spice or something you might drink as a tea. But the rest of the plant is edible, too, and a surprisingly strong flavored vegetable. It also is very crunchy and makes a really great addition to salads. But it is often not really sold in many places.

This is the Jerusalem Artichoke, another vegetable that originates within the Americas. To be exact, this is the root of a kind of sunflower. It got its name for being very similar in taste and tecture to the Artichoke. I honestly do not know, though, why it is called "Jerusalem Artichoke", because it does not have anything to do with Jerusalem.

The Potimarron is a kind of squash that - like basically all other forms of squash - originates in the Americas as well. It has a very nutty flavor. In Europe it was very popular in France for a long while, hence the french name. It has tons of meat and really makes for great stews!

This is a rutabaga, which originates from somewhere in northern Europe. We do not really know from where. All we know is, that it was a Swedish botanist who cultivates the form we still eat to this day in the 1620s. Which is why it is also called the "Swedish turnip". It does taste like a more bitter carrot, but makes really good addition to stews or can be served stamped.

This is the Chinese Artichoke and another root vegetable, that as the name suggest originates from China. It was cultivates in China in the late medieval period and has later made its way to Europe, especially France. It has a really sweet and nutty taste and can be eaten raw or in salads. Though there are dishes mashing the vegetable, too.

These are tigernuts, a vegetable that has been around forever. It originates in southern Europe, southern Asia and northern Africa. It is a dried fruit, with a sweet and earthy taste and it is known a lot in Spanish cuisine, but also in the cuisine of southern Asia.

Yacon is a root vegetable that originates with Peru, where it is still eaten, while the rest of the world mostly forgot about it. Well, except Japan, where it is currently getting more and more popular. It is a vegetable, but it has a very fruity taste.

I could now go on and name more vegetables from all around the world that were once grown and fed people, but got forgotten more and more in favor of the very limited diet made up of potatoes, corn, potatoes, peppers, cucumber, onion and tomatoes, that is basically what you will get to eat in most places.

And... Well, the thing about it is that... It is not really a good thing that we grow the same stuff everywhere. It is not good for us and it is not good for the environment. It is not good for those foods, either.

I really wish people would try and eat more of the stuff that originates with their region. And that they would eat the not-so-perfect looking foods as well. Because it is gonna be more sustainable in the end.

#solarpunk#food#vegetables#fruits#farming#agriculture#history#food history#sustainable living#sustainability#colonialism

325 notes

·

View notes

Text

82 notes

·

View notes

Text

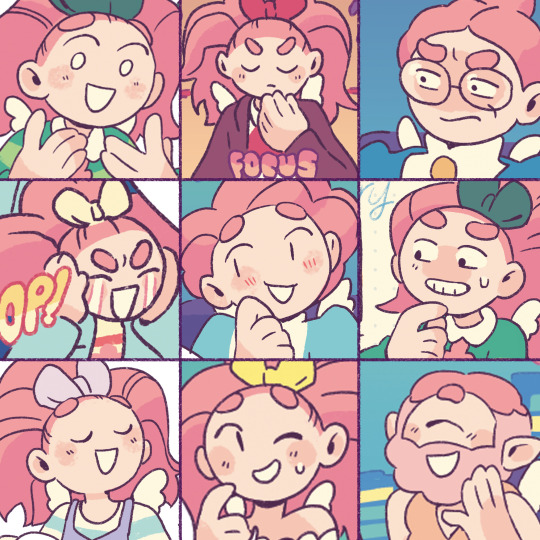

faces from TASTY: A HISTORY OF YUMMY EXPERIMENTS

OUT TODAY!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

#graphic novels#comics#nonfiction#food history#tasty: a history of yummy experiments#WOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOOO

73 notes

·

View notes

Photo

You know, I can and will complain about hygiene in a restaurant if need be but I am grateful we’ve passed the point where the restaurant needs to advertise that they don’t re-cook and re-serve the food scraps of previous diners. ( X )

[ID: A historic bill of fare, in old timey font and sepia-toned, which states “Our motto: Cleanliness, good cooking, and quick service. Only first quality goods are used here. No scraps taken back into the kitchen and cooked over again at this restaurant.”]

1K notes

·

View notes

Text

Happy Pokémon Day! February 27th is the anniversary of the first two Pokémon games’ release in Japan, and it’s a minor holiday in my house, as a fun excuse to make Pokémon inspired food, watch some Pokémon shows or movies (we’re going to watch Netflix’s new Pokémon Concierge this year!), and get excited about upcoming games and releases. This year, we’re making a Pokémon Sword and Shield inspired burger-steak curry and I’m making a dessert from the Pokémon Cookbook by Victoria Rosenthal. It’s one of my favorite fandom cookbooks – all the recipes are vegetarian or vegan, to get around the awkward question of where does the meat in the Pokémon universe come from?

But that’s not all we’re making! Ever since Nicki and Isabel were released, I’ve been dying to do a post about them and Pokémon’s infamous “Jelly Filled Doughnuts”, better – and more accurately! – known as onigiri.

Pokémon was released in the United States in 1998 via two Gameboy games: Pokémon Red and Pokémon Blue. The games quickly caught on to be one of the biggest pop culture phenomenon of the late 90’s and early 00’s, and as a kid at the heart of this explosion, I can’t overstate how much of a big deal it was. One of the great things about Pokémon – and probably why it has such lasting, widespread appeal – is that there are so many ways to interact with the franchise, and the marketing doesn’t skew hugely towards one gender or the other. Cool, tough Pokémon like Charizard got pretty similar billing to cute, pink Pokémon like Jigglypuff, and there were so many options for potential favorites that it was easy for any kid to find some creature to attach themselves to.

One of my petty complaints with Nicki and Isabel’s collection and books is the almost complete lack of mention of Pokémon and other anime that was really popular among kids in 1999. I know AG probably didn’t want to shell out for licensing deals with Nintendo or The Pokémon Company, but their stories just don’t feel accurate without discussing their prized binder of Pokémon cards or begging their parents to take them to see the Pokémon movie in theaters. Maybe the authors were just a little too old to get caught up in Pokémania?

I’ve also always thought its close overlap with the Beanie Babies crazy helped get millennial children like me very into the “gotta catch ‘em all” aspect of the franchise. Is this why I’m such a crazy toy collector as an adult? Who knows.

The Pokémon anime was one of the main ways kids like me got hooked on the franchise, because not everyone was allowed to have a Gameboy of their own (me), and not everyone liked video games, but even if you didn’t like video games, the cartoon might appeal to you. Although it was far from the first Japanese cartoon to air on US television, Pokémon was one of if not the first truly mainstream favorites of the 1990’s. 4Kids, the company in charge of dubbing the show into English, decided that American kids wouldn’t understand or be open to certain aspects of the show that reflected its Japanese roots, and so made a lot of strange choices in rewriting the script. One of the most notorious was deciding Brock’s rice balls were actually jelly filled doughnuts:

Onigiri – also known as omusubi or nigirimeshi – are balls of rice with a variety of fillings inside. They’re often compared to sandwiches, as an easy, quick, cheap meal or snack that combines carbs and other ingredients. While the concept of taking a rice ball and stuffing it full of other tasty treats goes way back to ancient Japan, the triangle shape became popular in the 1980’s thanks to a new machine that automated the filling process. Further developments over the last 40 years have created unique ways to prepackage onigiri without making the nori wrapping sticky. The ones we made were an attempt at recreating the “Hawaiian” (spam and pineapple) rice balls from our favorite food hall back in DC. One of my favorite pandemic indulgences was getting take out from the food hall, which often included a sampler of some of my favorite onigiri, and I haven’t been able to find anything close to similar where we are now. One of the many reasons I’m excited to move!

Even as a kid, I wasn’t convinced the food in the anime was fried dough with fruit jelly inside, because they sure look like rice. I also think 4Kids didn’t anticipate that Pokémon’s widespread popularity would inspire many of its fans – including me – to become absolutely obsessed with Japanese food and culture. I would’ve been more excited if they’d just been straight with me and shown more Japanese food on the show, and then probably begged my parents to make it or take me to a restaurant that made it. While I can’t confidently cite numbers of how many other people were first exposed to Japanese culture and food through Pokémon and franchises like it, I do think it’s a bit of a missed opportunity to highlight how things like this exposed kids like Nicki and Isabel to parts of a culture outside their own!

51 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Osias Beert + banquet still life

#osias beert#art history#still life#banquet#food#art#dutch golden age#baroque#decadence#paintings#hannibalcore#17th century#food history#oysters#hulderposts

2K notes

·

View notes

Text

Oh! the Roast Beef of Old England: Roast Beef, English Nationalism, Effeminacy and Epilepsy (ft. Lord Hervey)

While today if asked what the national dish of England is some might say bangers and mash, Yorkshire pudding or chicken tikka masala in the 18th century the answer was roast beef.

It was roast beef that was the star of the patriotic 18th century song The Roast Beef of Old England. Originally written by Henry Fielding for his play The Grub-Steet Opera (1731) and then reused in Don Quixote in England (1734) the more popular version was written by Richard Leveridge who set it to a catchier tune and added five new stanzas:

When mighty roast Beef was the Englishman's Food,

It ennobled our Veins, and enriched our Blood;

Our Soldiers were brave, and our Courtiers were good.

Oh the roast Beef of old England, and old

English roast Beef.

But since we have learn'd from all-conquering France,

To eat their Ragouts, as well as to dance,

We are fed up with nothing, but vain Complaisance.

Oh the roast Beef, &c.

Our Fathers, of old, were robust, stout, and strong,

And kept open House, with good Chear all Day long,

Which made their plump Tenants rejoice in this Song.

Oh the roast Beef, &c.

But now we are dwindled, to what shall I name,

A sneaking poor Race, half begotten-and tame,

Who sully those Honours, that once shone in Fame.

Oh the roast Beef, &c.

When good Queen Elizabeth sat on the Throne,

E're Coffee, or Tea, and such Slip-Slops were known,

The World was in Terror, if e'er she but frown.

Oh the roast Beef, &c.

In those Days, if Fleets did presume on the Main,

They seldom, or never, return'd back again,

As witness, the vaunting Armada of Spain.

Oh the roast Beef, &c.

Oh then they had Stomachs to eat, and to fight,

And when Wrongs were a cooking, to do themselves right;

But now we're a-I could, but good Night.

Oh the roast Beef, &c.

Leveridge's version espouses the masculine qualities roast beef making Englishmen "brave", "robust," and "strong". Fielding's version from Don Quixote in England contrasts this English masculinity with the non-roast beef eating "effeminate Italy, France, and Spain". (Edgar V. Roberts, Henry Fielding and Richard Leveridge: Authorship of "The Roast Beef of Old England")

[Politeness, print, after 1780, published by Hannah Humphrey, after John Nixon (1779), via The Metropolitan Museum of Art.]

A common element of English nationalist propaganda was to contrast the masculine beef eating Englishman with the effeminate frogs legs eating Frenchman. The satirical print Politeness compares the masculine John Bull to a stereotypical effeminate Frenchman. John Bull is depicted as a plainly dressed man, holding a pint of beer, with a Bulldog at his feet and a cut of beef hanging behind him. The Frenchman in contrast is depicted as foppishly dressed, holding a snuff-box, with an Italian Greyhound at his feet and a bundle of Frogs hanging behind him. John Bull says "You be D_m'd". The Frenchman responds "Vous ete une Bete". The caption narrates:

With Porter Roast Beef & Plumb Pudding well cram'd, Jack English declares that Monsr may be D------d. The Soup Meagre Frenchman such Language dont suit, So he Grins Indignation & calls him a Brute.

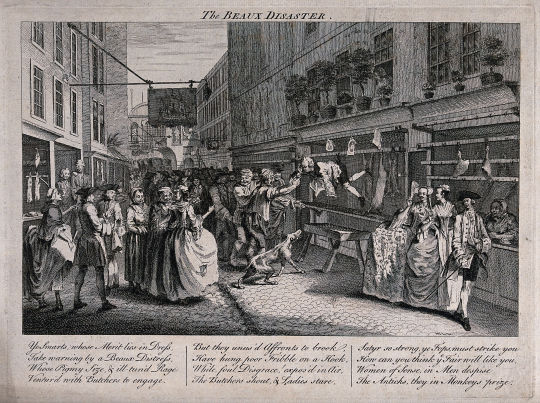

In 18th century English print culture the butcher became somewhat of a stock figure representing English masculinity. There was a series of prints in which a masculine butcher is depicted assaulting a fop. Often with bystanders cheering him on. Some of these prints identified the fop as a Frenchman (such as The Frenchman in London by John Collet and The Frenchman at Market by Adam Smith) but others either don't identify nationality or indicate that the fop is English.

[The Beaux Disaster, print, c. 1747, via The Wellcome Collection.]

The Beaux Disaster depicts the aftermath of an altercation between a butcher and a fop. The butcher has hung the fop up by the back of his breeches on a hook next to cuts of meet. A crowd of passersby point and laugh at the fop, enjoying his misfortune. The caption narrates:

Ye smarts whose merit lies in dress, Take warning by a beaux distress. Whose pigmy size, & ill-tun'd rage Ventured with butchers to engage. But they unus'd affronts to brook Have hung poor Fribble on a hook, While foul disgrace! expos'd in air, The butchers shout and ladies stare. Satyr so strong, ye fops must strike you How can ye think ye fair will like you, Women of sense, in men despise The anticks, they in monkeys prize.

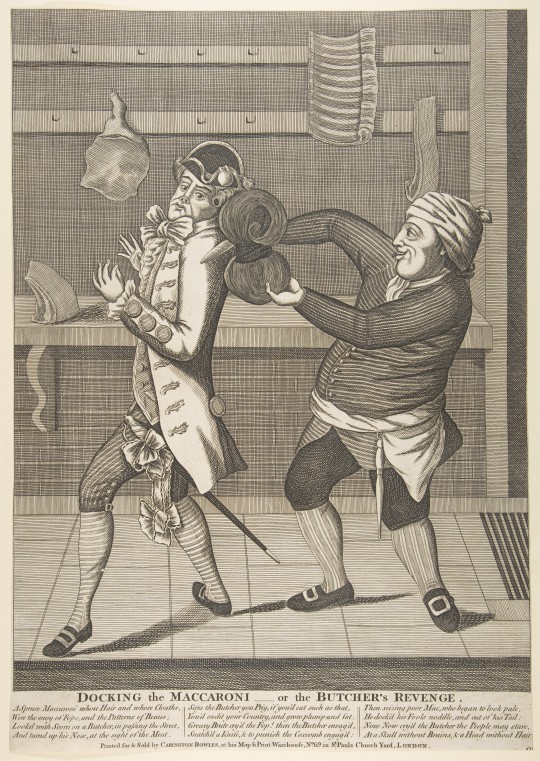

[Docking the Maccaroni–or the Butcher's Revenge, print, c. 1773, published by Carington Bowles, via The Metropolitan Museum of Art.]

Docking the Maccaroni–or the Butcher's Revenge depicts a butcher cutting off a macaroni's queue. Fashionable men in the late 1760s and 1770s would wear elaborate hairstyles sometimes with hair tied back into a 'club'. This hairstyle is a common element of macaroni satire (for a more flattering rendering of the style see George Simon Harcourt by Daniel Gardner). The caption narrates:

A Spruce Maccaroni whose Hair and whose Clothes, Were the envy of Fops, and the Patterns of Beaus; Looked with Scorn on a Butcher; in passing the Street, And turnd up his Nose, at the sight of the Meat. Says the Butcher you Pig, if you'd eat such as that, You'd credit your Country, and grow plump and fat. Greasy Brute cry's the Fop! then the Butcher enrag'd, Snatch'd a Knife, & to punish the Coxcomb engag'd: Then seizing poor Mac, who began to look pale, He docked his Fools noddle, and cut of his Tail: Now Now cry'd the Butcher the People may stare. At a Skull without Brains, & a Head without Hair.

The macaroni was often portrayed as a traitor to English culture not only for his love of french fashion but also his love of Italian pasta. The fabled 'macaroni club' was a reference to Almack's Assembly Rooms at 50 Pall Mall. (see Pretty Gentleman by Peter McNeil p52-55) The Macaroni and Theatrical Magazine (Oct 1772) explains that the origin of the word macaroni comes from:

a compound dish made of vermicelli and other pastes, which unknown in England until then, was imported by our Connoscenti in eating, as an improvement to their subscription at Almack's. In time, the subscribers to those dinners became to be distinguished by the title MACARONIES, and, as the meeting was composed of the younger and gayer part of our nobility and gentry, who, at the same time that they gave into the luxuries of eating, went equally into the extravagancies of dress; the word Macaroni then changed its meaning to that of a person who exceeded the ordinary bounds of fashion; and is now partly used as a term of reproach to all ranks of people, indifferently, who fell into this absurdity.

(Cited in Catalogue of Prints and Drawings in the British Museum edited by Frederic George Stephens and Edward Hawkins, vol.4, p.826)

Foppishly dressed men were blamed not only for the popularisation of pasta in England but also the growing disfavour for roast beef. A letter written to The Connoisseur in 1767 complains:

By Jove it is a shame, a burning shame, to see the honour of England, the glory of our nation, the greatest pillar of like, ROAST BEEF, utterly banished from our tables. This evil, like many others, has been growing upon us by degrees. It was begun by wickedly placing the Beef upon a side-table, and screening it by a parcel of queue-tail'd fellows in laced waistcoats.

(Volume 1, Edition 5)

With both his dress and diet the fop had betrayed English masculinity for French and Italian effeminacy.

Passed down by Lady Louisa Stuart* as an example of the "extreme to which Lord Hervey carried his effeminate nicety", when "asked at dinner whether he would have some beef, he answered, "Beef?— Oh, no!— Faugh! Don't you know I never eat beef, nor horse, nor any of those things?" Stuart was somewhat skeptical of this story wondering "Could any mortal have said this in earnest?"

*anonymously. Stuart wrote the introductory anecdotes included in the 1837 edition of The Letters and Works of Lady Mary Wortley Montagu.

While it's anyone's guess as to whether Hervey said these exact words it is true that he didn't eat beef. Not because he "courted" effeminacy with the "affected and almost finical nicety in his habits and tastes" as John Heneage Jesse suggests (in Memoirs of the Court of England from the Revolution in 1688 to the Death of George the Second) but for his health.

Lord Hailes explained:

Lord Hervey, having felt some attacks of the epilepsy, entered upon and persisted in a very strict regimen, and thus stopt the progress and prevented the effects of that dreadful disease. His daily food was a small quantity of asses milk and a flour biscuit : once a-week he indulged himself with eating an apple : he used emetics daily.

(The Opinions of Sarah Duchess-Dowager of Marlborough edited by Lord Hailes, p43)

Lord Hervey's doctor George Cheyne believed that "a total Milk, and Vegetable Diet, as absolutely necessary for the total Cure of the Epilepsy". (The English Malady, p254)

In An Account of My Own Constitution and Illness Hervey explains that he followed such a diet for three years on Cheyne's prescription eating "neither flesh, fish, nor eggs" but living "entirely upon herbs, roots, pulse, grains, fruits, legumes". (p969) However after three years he reintroduced white meet. He explains his diet in a letter to Cheyne, written on the 9th of December 1732:

To let you know that I continue one of your most pious votaries, and to tell you the method I am in. In the first place, I never take wine nor malt drink, or any liquid but water and milk-tea ; in the next, I eat no meat but the whitest, youngest, and tenderest, nine times in ten nothing but chicken, and never more than the quantity of a small one at a meal. I seldom eat any supper, but if any, nothing absolutely but bread and water ; two days in the week I eat no flesh ; my breakfast is dry biscuit not sweet, and green tea ; I have left off butter as bilious ; I eat no salt, nor any sauce but bread sauce. I take a Scotch pill once a week, and thirty grains of Indian root when my stomach is loaded, my head giddy, and my appetite gone. I have not bragged of the persecutions I suffer in this cause ; but the attacks made upon me by ignorance, impertinence, and gluttony are innumerable and incredible.

Intriguingly in An Account of My Own Constitution and Illness Hervey focuses more attention on colic than epilepsy, dismissing his seizures as rare, but admits he had "two this year". This leads to the impression that his diet was prescribed to treat colic rather than epilepsy and Cheyne did prescribe a milk and vegetable diet in cases of "extreme Nervous Cholicts". (p167) Perhaps it was prescribed to treat both. But why downplay epilepsy in an account of his own illness?

While some enlightenment doctors approached epilepsy with a more scientific approach, superstitions still remained. Some believed epilepsy was a form of lunacy that was controlled by the moon (the word lunatick coming from luna). In An Historical Essay on the State of Physick in the Old and New Testament Dr. Jonathan Harle claimed that "people in this distemper are most afflicted at full or change of the moon." (p124)

Many believed epilepsy was caused by possession and this belief was supported by the bible. Mark 9:17-27, Matthew 17:14-18 and Luke 9:37-43 tell the story of a man who brings his possessed son to Jesus who "rebuked the unclean spirit, and healed the child". The boy's symptoms resemble those of an epileptic seizure and these bible verses are cited by Dr. Jonathan Harle as "an exact description of one that is an epileptick (had the falling sickness) or lunatick". (p124) Harle claimed that was "a truth as plain as words can make it" that some people with epilepsy were "possess'd by the devil". (p22)

Epilepsy was also believed to be caused by sexual depravity. The popular anti-masturbation pamphlet Onania: or, the Heinous Sin of Self-Pollution claimed masturbation caused epilepsy (p23). Onanism: or, a treatise upon the disorders produced by masturbation, or, The dangerous effects of secret and excessive venery claimed that a 14-year-old boy "died of convulsions, and of a kind of epilepsy, the origin of which was solely masturbation". (p19)

With the stigma surrounding epilepsy its no wonder that Hervey kept his seizures secret only telling a select few. One of the people he trusted with this secret was his lover Stephen Fox. Hervey describes having a seizure while at court and keeping it hidden from the Royal Family in a letter to Fox written on the 7th of December 1731:

I have been so very much out of order since I writ last, that going into the Drawing Room before the King, I was taken with one of those disorders with the odious name, that you know happen'd to me once at Lincoln's Inn Fields play-house. I had just warning enough to catch hold of somebody (God knows who) in one side of the lane made for the King to pass through, and stopped till he was gone by. I recovered my senses enough immediately to say, when people came up to me asking what was the matter, that it was a cramp took me suddenly in my leg, and (that cramp excepted) that I was as well as ever I was in my life. I was far from it ; for I saw everything in a mist, was so giddy I could hardly walk, which I said was owing to my cramp not quite gone off. To avoid giving suspicion I stayed and talked with people about ten minutes, and then (the Duke of Grafton being there to light the King) came down to my lodgings, where * * * I am now far from well, but better, and prodigiously pleased, since I was to feel this disorder, that I contrived to do it à l'insu de tout le monde. Mr. Churchill was close by me when it happened, and takes it all for a cramp. The King, Queen, &c. inquired about my cramp this morning, and laughed at it ; I joined in the laugh, said how foolish an accident it was, and so it has passed off ; nobody but Lady Hervey (from whom it was impossible to conceal what followed) knows anything of it.

33 notes

·

View notes