#forsyth county

Video

Cumming, Forsyth County, GA

Black Americans have had 15 million acres of land stolen through terror, lynchings and genocide down to 1 million.

This is just one of many that deal with the ethnic cleansing of Black Americans by white mobs. You may have heard of Oprah doing an episode in 1987 about that county. (Episode: Oprah Visits a County Where No Black Person Had Lived for 75 Years.) Sundown towns, of course. No longer completely completely white, it is still largely white. Mrs. Elon Osby and every last descendant needs to gather their docs and get every single acre back. Everybody living all comfortably there and shit gotta go. It is what it is. We’ve been needed an Anti-Black Hate Crime bill. But the Democrats, who Black Americans have loyally voted for with no tangibles in return, obviously feel it’s of no concern. The likes of Buffalo, anyone?

Did I mention this town is close by Oscarville, the Black American town under that man-made lake, Lake Lanier? 1912.

Add this onto the reparations claim and charge genocide.

SN: An almost silent shakedown almost went down in the small Black town of Mason, Tennessee not too long by the state’s comptroller. Thank goodness people caught wind outside of that town and seize of control (before a shift) was unsuccessful.

#reparations#reparations now#forsyth county#georgia#lake lanier#oscarville#cumming georgia#black american history#american history

460 notes

·

View notes

Photo

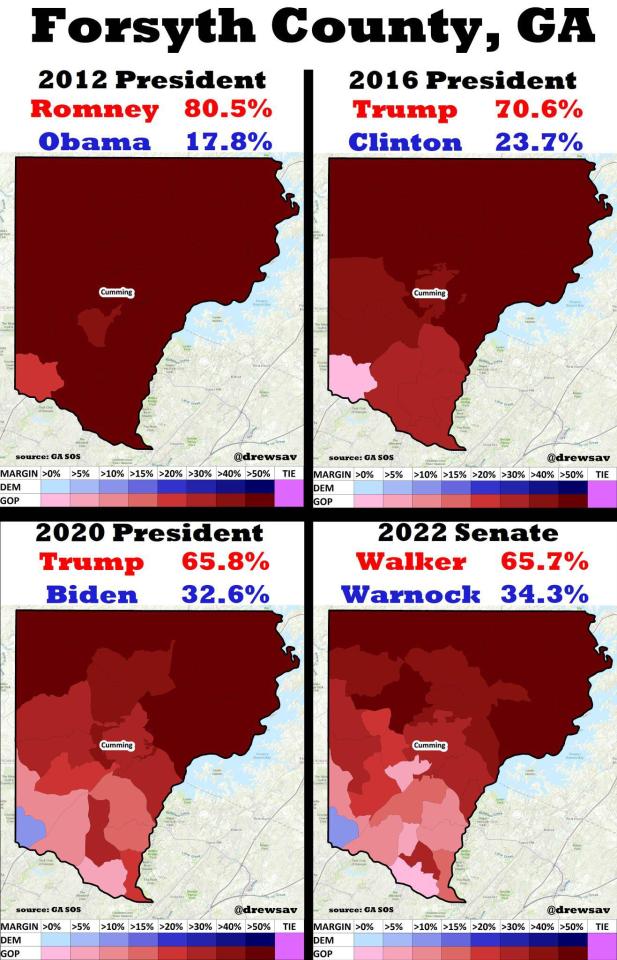

Political shifts in Forsyth County, Georgia, 2012-2022.

115 notes

·

View notes

Text

Once you get past the Batman researcher part it's a good article about censorship in schools and the pushback against gender ideology as led back to don’t say gay.

In this undated photo provided by Rebecca Hale, Marc Tyler Nobleman poses for a portrait. The author's clash with a Georgia school district over a mention of someone's homosexuality in a presentation highlights the reach of conservatives' push for what what they call parents' rights. Nobleman at first complied with a request not to mention that the son of Batman's co-creator was gay but then rebelled. He and LGBTQ+ advocates say the Forsyth County district in suburban Atlanta was wrong. The district says schools shouldn't engage in such discussions without parents knowing in advance. (Rebecca Hale via AP)

ATLANTA (AP) — Marc Tyler Nobleman was supposed to talk to kids about the secret co-creator of Batman, with the aim of inspiring young students in suburban Atlanta's Forsyth County to research and write.

Then the school district told him he had to cut a key point from his presentation — that the artist he helped rescue from obscurity had a gay son. Rather than acquiesce, he canceled the last of his talks.

“We’re long past the point where we should be policing people talking about who they love,” Nobleman said in a telephone interview. “And that’s what I’m hoping will happen in this community.”

State laws restricting talk of sexual orientation and gender identity in schools have proliferated in recent years, but the clash with Nobleman shows schools may be limiting such discussions even in states like Georgia that haven’t officially banned them. Some proponents of broader laws giving parents more control over schools argue they extend to discussion of sex and gender even if the statutes don’t explicitly cover them.

Eleven states ban discussion of LGBTQ+ people in at least some public schools in what are often called “Don’t say gay” laws, according to the Movement Advancement Project, an LGBTQ+ rights think tank. Five additional states require parental consent for discussion, according to the project.

Legislation restricting LGBTQ+ rights gained steam this year, but suppression is not new. A school district in New Jersey, which requires curriculums to be LGBTQ-inclusive, tried to bar a valedictorian from discussing his queer identity during a graduation speech in 2021. That year, a federal judge ordered an Indiana district to give the same privileges to a gay-straight alliance as to other extracurricular groups. Two years later, Indiana passed a law banning discussion of LGBTQ+ people in grades K-3.

Schools nationwide have been challenged on books with LGBTQ+ themes or characters, and many have removed them, including Forsyth County, which has been a battleground in the politics of schooling.

LGBTQ+ advocates say Nobleman bumped up against a moral panic fomented by conservatives seeking to roll back acceptance.

“The idea that these folks are saying that they just don’t want to talk about it at all is very disingenuous,” said Cathryn Oakley, a lawyer for the Human Rights Campaign, a leading advocacy group. “What they mean is they don’t want views other than theirs to be expressed. And they believe that that means everyone should have to hear what they believe.”

Discussion of straight people with traditional gender identities is everywhere, she said, and if all discussion of sexuality is going to be banned, Oakley said, “then you certainly better not be teaching ‘Romeo and Juliet.’"

Nobleman, a self-described “superhero geek" who lives in the suburbs of Washington, D.C., is best known as the author of “Bill the Boy Wonder: The Secret Co-creator of Batman." It lays out the story of Bill Finger, the long-uncredited author who helped create Batman and other comic book characters.

Finger died in obscurity in 1974, with artist Bob Kane credited as Batman’s only creator. Finger’s only child was a son, Fred Finger, who was gay and died in 1992 at age 43 of AIDS complications. Bill Finger was presumed to have no living heirs, meaning there was no one to press DC Comics to acknowledge Finger's work.

But Nobleman discovered Fred Finger had a daughter, Athena Finger. That, he said, is a showcase moment of the presentation he estimates he has given 1,000 times at schools.

“It’s the biggest twist of the story, and it’s usually when I get the most gasps," Nobleman said. “It's just a totally record-scratch moment.”

Nobleman’s research helped push DC Comics into reaching a deal with Athena Finger in 2015 to acknowledge her grandfather and Kane as co-creators. That led to the documentary “Batman & Bill,” featuring Nobleman.

In Forsyth County, the author gave his first presentations at Sharon Elementary on Aug. 21. After Nobleman mentioned in his first talk that Fred Finger was gay, the principal handed him a note during his second talk that said, “Please only share the appropriate parts of the story for our elementary students.”

Forsyth County schools spokesperson Jennifer Caracciolo said that just mentioning Fred Finger was gay isn't the problem. But she said it led to questions from students, meaning Nobleman and students might discuss sexuality without parents being warned.

In the past three years, conservatives in the 54,000-student district have tried to tamp down diversity policies and sexually explicit books they view as immoral.

The district was sued by a conservative group called the Mama Bears after banning a member of that group from reading explicit book excerpts at meetings. A federal judge ruled the policy unconstitutional.

The district was also warned by the U.S. Department of Education after pulling some books from libraries, with federal officials saying the discourse may have created a hostile environment that violated federal laws against race and sex discrimination.

Nobleman’s discussion of sexual orientation has nothing to do with the state English language arts learning standards his presentation was supposed to bolster, Caracciolo said.

“We have a responsibility to parents and to guardians that they will know what students are learning in school,” Caracciolo said.

Nobleman said he was blindsided and agreed to drop the reference to Fred Finger's sexual orientation in remaining presentations that day, as well as in three at another school the next day. But by the morning of the third day, Nobleman started fielding questions from reporters after the principal at Sharon Elementary sent an electronic message to parents apologizing for the mention of Fred Finger's homosexuality.

“This is not subject matter that we were aware that he was including nor content that we have approved for our students," Principal Brian Nelson wrote. “I apologize that this took place. Action was taken to ensure that this was not included in Mr. Nobleman's subsequent speeches and further measures will be taken to prevent situations like this in the future.”

And so, on the third day he was presenting, after a discussion with district officials, Nobleman refused to give the last two of his scheduled presentations if required to omit Finger's sexual orientation.

Many parents have applauded Forsyth County's actions, Caracciolo said. Cindy Martin, chair of the Mama Bears, said Nobleman should be “ashamed of himself."

She argues that a 2022 Georgia law bans discussion of sexuality without parental consent for any minor because it gives parents “the right to direct the upbringing and the moral or religious training” of their children.

“No one has the right to talk to a child about sexuality unless it’s the parent, or the parent has given permission," Martin said. "Mr. Nobleman did not have permission. So he went against Georgia law.”

Matt Maguire, a Sharon Elementary parent who had a daughter who attended one of Nobleman's presentations, said he was disappointed by the message and felt the school district was being bullied by Martin and others into “reactionary” censorship.

The mere mention of the word “gay” didn't merit claims made online by critics that Nobleman was “ grooming or sexualizing children," he said, and it ignored that some Sharon Elementary students have gay parents.

“It didn't sit right with me. It made me feel like certain parts of our community were being kept as a dirty secret,” Maguire said. “I couldn't imagine coming from a family with gay members and reading that apology just for saying the word ‘gay.’”

#Marc Tyler Nobleman#Batman#usa#Georgia#Atlanta#Forsyth County#Bill Finger#Rest In Peace Fred Finger#Batman & Bill#Pushback over gender ideology has led back to don't say gay#Drop the TQ+

8 notes

·

View notes

Text

The cottonfields of Georgia were once worked by the enslaved. REUTERS/Tom Lasseter

WASHINGTON

We sat in the pews of a Methodist church last summer, my family and I, heads bowed as the pastor began with a prayer. Grant us grace, she said, to “make no peace with oppression.”

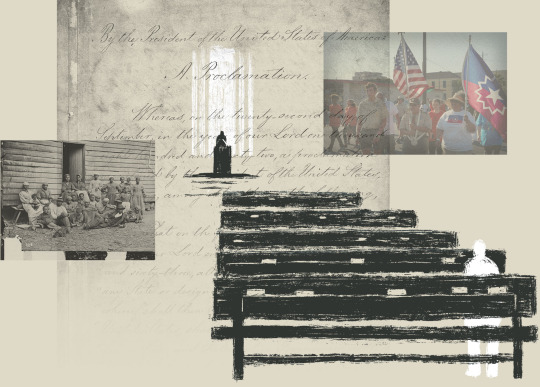

Our church programs noted the date: June 19, or Juneteenth, the day on the federal calendar that celebrates the emancipation of Black Americans from slavery. The morning prayer was a cue.

The kids were ushered from the sanctuary to Sunday school. My sons – one 11, the other 8 at the time – shuffled off to lessons meant for younger ears.

The sermon, delivered by a white pastor to an almost entirely white congregation, was headed toward this country’s hardest history.

“We are a nation birthed in a moment that allowed some people to stand over others,” she said from the pulpit, light flooding through the stained glass behind her. “We’ve all been a part of taking what we wanted. White people, my community, my legacy, my heritage, has this history of taking land that did not belong to us and then forcing people to work that land that would never belong to them.”

The pastor did not know that I was months into a reporting project for Reuters about the legacy of slavery in America. It was an idea that came to me in June 2020, shortly after returning to the United States after almost two decades abroad as a foreign correspondent.

We had moved to Washington just 18 days after George Floyd was killed by a white police officer in Minneapolis, and in our first weeks back, I found myself drawn to the steady TV coverage of protests from coast to coast. I read about the dismantling of Confederate statues on public land – almost a hundred were taken down in 2020 alone. I thought about my own childhood, about growing up in Georgia. And I wondered: Had this country, which I had yet to introduce to my sons, ever truly reckoned with its history of slavery?

REUTERS/Photo illustration REUTERS/Photo illustration

I wondered, too, about our most powerful political leaders. How many had ancestors who enslaved people? Did they even know? I discussed the idea with my editors, who greenlighted a sweeping examination of the political elite’s ancestral ties to slavery. They also raised another question: What might uncovering that part of their family history mean to today’s leaders as they help shape America’s future?

A group of Reuters journalists began tracing the lineages of members of Congress, governors, Supreme Court justices and presidents – a complicated exercise in genealogical research that, given the combustibility of the topic, left no room for error.

Henry Louis Gates Jr, a professor at Harvard University who hosts the popular television genealogy show Finding Your Roots, told me that our effort would be “doing a great service for these individuals.”

“You have to start with the fact that most haven’t done genealogical research, so they honestly don’t know” their own family’s history, Gates said. “And what the service you’re providing is: Here are the facts. Now, how do you feel about those facts?”

And there was more to the project, something I needed to do, if only out of fairness. As a native of Mississippi who grew up in Georgia, I would examine my own family’s history. A passing remark made by my grandfather long ago gave me reason to believe my experience wouldn’t be as joyous as the advertisements I saw for online genealogy websites. Instead of finding serendipitous connections to faraway lands, I suspected I would find slavery on the red clay of Georgia.

But all of that was for work. It wasn’t for Sunday church, I thought, sitting next to my wife. My mind wandering, I looked down at the Rolex on my wrist.

This is the story that I tell myself: Those are things that I earned, paid for with hard work. I am a high school dropout. My mother is a high school dropout. My father is a high school dropout. My sister is a high school dropout. My first home was in a southern Mississippi trailer park. My mother was pregnant with me at the age of 19. My dad left our lives early.

I got my GED. I moved from a community college to the University of Georgia, working as a short-order cook while earning a bachelor’s degree in journalism.

For me, church is a place that offers a soothing sense of order, of ritual. That morning, I didn’t feel comfortable. I resented the pastor. I was there to listen to the choir and contemplate a Bible verse or two, not to be lectured. Especially about a subject I was grappling with personally and professionally.

“We would swear with our last breath that we do not have a racist bone in our bodies,” she continued. “But some of us were born in a lineage of people who take land that is not ours and enslave other people.”

Her words would come close to the facts that my reporting surfaced in the months ahead. Still, on this Juneteenth, I was done listening.

After the service, I walked to the car with my wife and sons. I didn’t talk with them about the sermon as we headed to our home on the outskirts of Washington. Ours is a street of rolling green lawns and shiny Cadillac Escalades. On the edge of the U.S. capital, a city where some 45% of the population is Black, the suburb where we live is about 7% Black. It was an inviting place for a white man to escape the pastor’s message.

That cocoon soon started to unravel. I had begun a journey that would take me back to places I held dear but had not truly known. What I would come to learn in researching my ancestors didn’t tarnish my love for family. At times, though, I did worry that I was betraying them.

It also left me with two questions I have yet to answer. What do I tell my sons about what I found, and what does it say about their country?

Introducing America

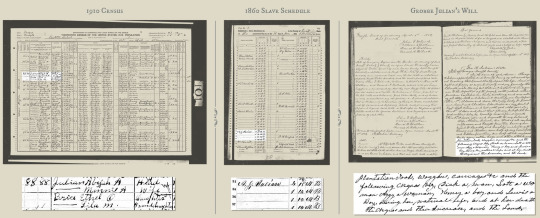

Throughout 2022, our reporting team assembled family trees for Congressional members. We connected one generation to the previous, like puzzle pieces snapping one to another, extending years before the end of the U.S. Civil War in 1865. We learned to decipher census documents written in sometimes bewildering cursive. Enlisting the help of board-certified genealogists, we became comfortable with the types of inconsistencies that surface in the old papers: names slightly misspelled, ages off by a few years, children who disappear from households as they die between censuses or marry young.

For months, my attention was drawn to the complexity of the task, and I scoured websites for documents that went beyond census records: certificates of birth, death and marriage, obituaries, military service forms, family Bibles.

The work was painstaking, and a welcome diversion. Each time I thought about building out my own family history, I winced at the subject coming close. Those were my people, my history.

Eventually, I knew I had to get started.

My wife and I were born in America. Both of us are journalists. We met in Baghdad, there to cover the war in Iraq. We married later while living in Russia, had our first son in China, our next in India. After two years in Singapore, we decided it was time to take the boys home to America, a land they’d visited on summer trips to their grandmothers’ houses in Georgia and Virginia but hardly knew.

Their introduction began less than three weeks after the May 25 death of George Floyd, as soon as we rode in from the airport. As we approached shuttered stores and boarded-up windows in downtown Washington, our younger son looked at the graffiti and banners and asked what the letters BLM stood for. My wife and I spelled it out – Black Lives Matter – and told him about Floyd’s death. Six at the time, he had no idea what we were talking about. His older brother explained the protests were to help Black people. Then he reminded him that their uncle, my sister’s husband, is Black. Our little boy went quiet. In the wake of George Floyd’s killing, protesters took to the streets across America.

REUTERS/Photo illustration In the wake of George Floyd’s killing, protesters took to the streets across America. REUTERS/Photo illustration

Last spring I began to trace my family’s lineage in detail. I had gone through this process for dozens of members of Congress. Now I was looking at my own mom. As I started a family tree, I did not like typing her name – it felt like I was crossing a line. I opened the search page at Ancestry.com and entered the names of her parents, Harriet and Brice.

Brice was 69 or so when he visited us in Atlanta during the summer of 1994. I was a teenager. Joseph Brice James was my grandfather, but we just called him Brice. Like my own father, he hadn’t been part of our life. He lived in Chicago and had worked as a traveling salesman. The trip may have been one last effort by him to connect. He wasn’t well and would die about eight years later.

It would be that visit – really, just one line that Brice muttered – that came back to me in the summer of 2020 and started my own personal reckoning.

My Grandfather’s Words Joseph Brice James. (Courtesy: Tom Lasseter)

Here’s what I remember: Brice wanted to see the farm where his ancestors, our ancestors, lived. My mother drove, and my sister and I sat in the backseat of our family’s aged Toyota Corolla. The address Brice helped direct us to was about an hour out of Atlanta. My mother had been there before, too, but my ancestors had sold it off, parcel by parcel, starting around 1947. We pulled over in front of a clapboard farmhouse.

I wasn’t sure why we were there, or who might have once lived on the farm. Brice, a gaunt figure with closely cropped hair and large glasses, didn’t volunteer much. I walked alongside him in silence, across a field spotted with pine trees, on the edge of a lake. Then Brice paused, flicking his wrist toward an old well and said: “The slaves built that.” A moment passed and he kept walking, offering nothing further.

Those four words stayed with me, though, in the way that happens with some white families from the South: I now knew, if I wanted to, that somewhere in my history there was a connection to slavery. The farmhouse in Georgia, once owned by the ancestors of Reuters journalist Tom Lasseter.

REUTERS/Tom Lasseter

Where to begin? Before prying into Brice’s side, I decided to look somewhere more familiar. The census shows my mother’s maternal grandmother as Cornelia Benson. I grew up calling her Grandma Horseyfeather, a nickname given her by my mother’s generation, the product of a long-ago children’s tale.

Looking at the 1940 census, there was Cornelia Benson of Brooks County, Georgia. I knew Brooks County as a place of Spanish moss, where we caught turtles and lizards in my childhood. I loved Thanksgiving at 618 North Madison Street, where a dirt driveway led to the back stairs and then a kitchen with long rows of casseroles. Grandma Horseyfeather, born in 1898, spoke in a slow, deep drawl. She wore lace to church. I adored her and I adored Brooks County.

At home in Atlanta, I felt lost at times, my single, working-class mom stretching one paycheck to the next. But in Cornelia Benson’s house, I felt at ease. My identity was simple: I was a white kid descended from generations of white people from the deepest of south Georgia.

As a child, I did not ask what it meant to belong to a place like Brooks County. Now I wanted to know. Cornelia Benson with Tom Lasseter as infant (left); Tom Lasseter during a childhood visit to Quitman, Georgia. (Courtesy: Tom Lasseter)

A story came to mind. I was young, and the grownups were visiting at the dining table. Someone started to tell a story about life in Quitman, the town in Brooks County where Grandma Horseyfeather lived. It was about the Ku Klux Klan and its marches.

The Klan would saunter down the street, wearing hoods and sheets, thinking no one knew who they were. The story’s punchline: All the “colored boys” – meaning Black men – knew who was wearing those sheets. They could see the shoes the white men were wearing. And who do you think shined those shoes?

I remember a tittering of laughter ripple around the table.

It was a vignette I sometimes trotted out when discussing the South. I’d shake my head and show a rueful half-frown that communicated disapproval, but not too much. My Brooks County relatives didn’t quite fit the pastor’s words. I knew they had some racist bones in their body. Still, these were my people. They didn’t mean any harm.

Reading back over the story after I wrote it down last year made me wonder what I didn’t know. So I did something that had never before occurred to me: I looked up the history of Brooks County, Georgia. It did not lead anywhere good.

In 1918, at least 13 Black people were killed in a rash of lynchings by mobs in Brooks that cemented its reputation for bloodshed. A flag that hung from the NAACP national headquarters in New York City, 1920-1928 (Source: NAACP via Library of Congress). Lynchings in Brooks County, Georgia, in the early 20th century cemented its reputation for racism and bloodshed.

REUTERS/Photo illustration

“There were more lynchings in Brooks than any county in Georgia” at the time, according to a 2006 paper examining lynchings in southern Georgia. Among the 1918 victims: Near the county line, a pregnant woman was tied to a tree and doused with gasoline before her belly was slit open with a knife and her unborn child tumbled to the dirt. The woman was shot hundreds of times, “until she was barely recognizable as a human being.” And then both her and her fetus’ burial spots were marked by a whiskey bottle with a cigar placed in its neck, according to the paper – “Killing Them by the Wholesale: A Lynching Rampage in South Georgia” – published in The Georgia Historical Quarterly.

I toggled my Internet browser to census records. Cornelia Benson and her husband weren’t yet living in Brooks County as of the 1920 census. They moved there between 1920 and 1930. I felt relieved, clean. I didn’t know any of that history. No one had told me.

But the more I learned, the more I played out the possibilities, the more troubled I felt about the Ku Klux Klan anecdote.

One morning in my home office, I pulled out a cell phone to record my thoughts about those memories. As I did, I heard the wood floorboards creaking. It was one of my sons walking outside the room. I waited for him to go downstairs before starting. When I later listened to my recounting of the Ku Klux Klan story, I noticed I’d used the phrase “Black people” rather than “Colored boys.” Without thinking, I’d cleaned the story up around the edges, making it easier to tell.

‘Mules, Oxen…and The Following Negroes’

Brice died in 2001. I never learned anything else from him about that well on the property our ancestors owned. Having read through the Brooks County material, it was time to see what I might find out about Brice’s side of my family.

I knew my grandfather was born in Canada, but that his side of the family was somehow connected to that land in Georgia. Using Ancestry.com, I found a 1948 border crossing document for him, with the names of his father and mother. I took those names and found his parents’ 1921 marriage license in Fergus County, Montana.

I noticed that his mother’s maiden name was Lila M. Brice, and that her parents were Ethel Julian and Joseph T. Brice. I looked for Ethel Brice. There she was, in the 1910 census. She was living with her daughter Lila in Forsyth County, Georgia, after a divorce – back in the household of her father, a man whose name I had never before heard: Abijah Julian.

The trip to the farm house in 1994 was in Forsyth County. The old clapboard house was built in the 1800s. And the well that Brice mentioned, the one that he said enslaved people built, sat right next to the house.

From one census to the next, I followed Abijah, a name from the Old Testament.

Information about the Julian family wasn’t hard to find once I started looking.

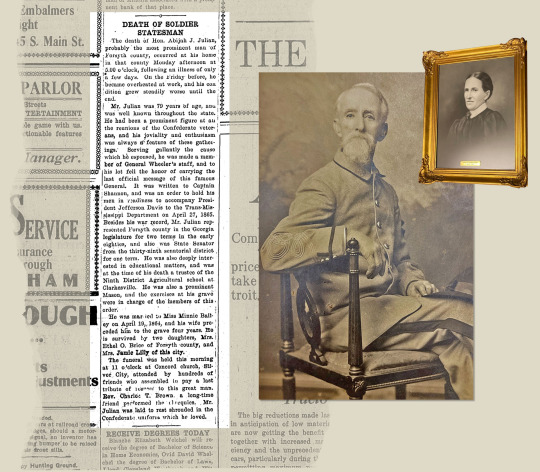

Working my way backwards, I learned Abijah Julian died in 1921. His passing was marked in The Gainesville News by an item headlined “DEATH OF SOLDIER STATESMAN.” Placed high in the article was the fact that Abijah Julian was part of a Confederate cavalry general’s staff during the Civil War, and that in his later years he “had been a prominent figure at all the reunions of the Confederate veterans.” The piece ended with these words: “Mr. Julian was laid to rest shrouded in the Confederate uniform which he loved.” Abijah Julian, seated, was buried in a Confederate uniform. In an account by his wife, Minnie Julian, she described him returning from war “broken in health and spirit. Negroes free, stock stolen and money – Confederate – valueless.” (Sources: Historical Society of Cumming/Forsyth County, Georgia. Newspaper clipping: The Gainesville News, June 1921)

He had served in Georgia’s state legislature for three terms. I looked for more details about him and his ancestors before the Civil War.

Abijah’s father, also a member of the state legislature, died in 1858 at home in Forsyth County, according to press reports. It was just a couple months before Abijah’s 16th birthday.

Some four years later, Abijah went to war against the United States. In 1864, a year before the Civil War ended, he married a woman in Alabama, the daughter of a doctor, who moved to the Julian farm. In an account by his wife, Minnie Julian, she described Abijah returning home after the war, “broken in health and spirit. Negroes free, stock stolen and money – Confederate – valueless.” In the very next sentence, however, she noted they still had 600 acres of land.

Her words signaled that Abijah had enslaved people. But I needed more proof.

In addition to the usual household census forms, in 1850 and 1860 the U.S. government created a second document for the census takers to fill out in counties in states where slavery was legal. It’s referred to as a slave schedule, and it lists by name men and women who enslaved people, under the column “SLAVE OWNERS.” The form gives no names of the human beings they enslaved. Instead, it tabulates what the document refers to as “Slave Inhabitants” only by the person’s age, gender, color (B for Black or M for Mulatto, or mixed race) and whether they were “Deaf & dumb, blind, insane or idiotic.”

After you find a slaveholder on the household census form, matching them to the slave schedule can be complicated. In some counties, multiple men of the same or similar name enslaved people. And of course, not every head of household in a county enslaved people, so fewer names are listed on the slave schedule than on the population census. Fortunately, the households on the two documents are typically listed in the order they were counted by the census-taker – meaning if you see the same residents’ names close by, in the same sequence, you’ve likely found the same person on the two forms.

In 1860, on a slave schedule in Forsyth, I found my ancestor listed on line 34 as A.J. Julian. He was 17-years-old at the time. There were four entries for his “Number of Slaves” column – four males, ages from 10 to 18.

There was more. When Abijah’s father, George Julian, died in 1858, he left a will.

One key to unlocking the identities of those who were enslaved is through the estate records of white families who claimed ownership of them. In many cases, wills give the first names of the Black men, women and children bequeathed from one white family member to another.

In his will, George listed property “with which a kind providence has blessed me.” To wife Adaline, George bequeathed “mules, oxen, cattle, hogs and other stock, and plantation tools, wagons, carriages and the following Negros…”

There were five enslaved people left to George’s wife, the will said, with the provision that “the negros and their increase” – that is, their children – would go to Abijah after his mother’s death. George Julian also left four enslaved children to Abijah, himself a teenager at the time.

And, in a separate item, Julian wrote that an enslaved woman and three children should “be sold” to pay his debts.

The will was difficult reading. Lumped in with oxen and kitchen furniture, plantation tools and wagons, were human beings. And “their increase.”

The will listed names of the enslaved kept by the family: Dick, Lott, Aggy, Henry, Lewis, Ellick, Jim, Josiah and Reuben.

The document was dated 1858 – close enough to emancipation that I might have a chance at tracing some of them forward, especially if they used the last name Julian. Perhaps there would be a chance of finding those same names in Forsyth in the 1870 census, when, finally free, Black people were listed by name and household.

Something kept happening, however, when I looked for those names. I’d see likely matches in one or two censuses, and then they disappeared after the 1910 census in Forsyth.

It took me a few minutes of research to figure out why I was losing track of the descendants of the people George Julian enslaved. It was a history drenched with blood, and it drew much closer to mine than I had realized.

The Search for Descendants of The Enslaved

ATLANTA

In 1912, Virginia native Woodrow Wilson became the first Southerner since the U.S. Civil War to be elected president. And the white residents of a county in Georgia, where my ancestors lived, unleashed a campaign of terror that included lynchings and the dynamiting of houses that drove out all but a few dozen of the more than 1,000 Black people who lived there.

The election was covered in the classrooms of the Georgia schools I attended. If the racial cleansing of Forsyth County was mentioned, I didn’t notice.

That history explains the difficulty I had looking for the descendents of the people enslaved by my ancestor Abijah. By 1920, their families and almost every other Black person had fled the county.

From left: The Forsyth County Courthouse in Cumming, pictured in 1907. Built in 1905, it was destroyed by fire in 1973. (via Digital Library of Georgia). The Atlanta Georgian newspaper reports on the lynching of Rob Edwards, September 10, 1912. (Source: Ancestry.com). U.S. President Woodrow Wilson.

They were forcibly expelled under threat of death after residents blamed a group of young Black men for killing an 18-year-old white woman in September 1912. A frenzied mob of white people pulled one of the accused from jail, a man named Rob Edwards, then brutalized his body and dragged his corpse around the town square in the county seat of Cumming. Two of the accused young Black men, both teenagers, were tried and convicted in a courtroom. They too died in public spectacle, hanged before a crowd that included thousands of white people.

There were also the night riders, white men on horseback who pulled Black people from their homes, leaving families scrambling and their houses aflame. The violence swept across the county, washing across Black enclaves not far from the farm where my ancestor, Abijah, lived at the time.

In 1910, the U.S. Census showed 1,098 Black people living in Forsyth. Ten years later, the 1920 census counted 30.

‘Night Marauders’

Until last year, I had never heard of this history. I had a dim memory of news reports about white residents in Forsyth attacking participants in a peaceful march for racial equality – not during the tumultuous Civil Rights era but in the 1980s. I watched video clips from an early episode of “The Oprah Show” – a telecast from 1987 when talkshow star Oprah Winfrey went to Forsyth to try to make sense of what was happening there. Some locals in the audience were unrepentant. Footage shows that crowds on the street and a man, to Oprah’s face, were not shy about using racial slurs on national television.

I learned about the 1912 violence in Forsyth after a genealogist who worked with Reuters sent me a note pointing out that my ancestor Abijah Julian appeared in Blood at the Root, a 2016 book that chronicled the bloodshed there. I already knew Abijah had enslaved people and adhered to the “Lost Cause” – the view that the South’s role in the Civil War was just and honorable.

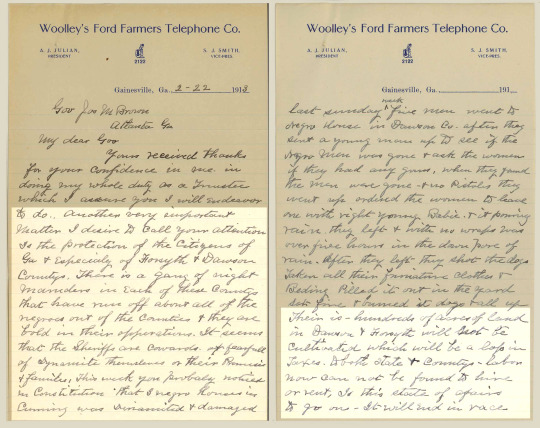

About four months after the terror in Forsyth began, Abijah wrote a letter to the governor of Georgia in February 1913. He was asking for help to quell the chaos unleashed by “night marauders” who had “run off about all of the negroes.” Here’s part of his letter: A letter Abijah Julian wrote to the governor of Georgia.

(Courtesy: Kenan Research Center at the Atlanta History Center.)

During that week alone, Julian wrote, “3 negro houses” in Cumming had been damaged by dynamite. The letter did not suggest any anguish for the Black people who’d been terrorized. What concerned Abijah Julian was his fields and who would farm them.

The Julian land stretched hundreds of acres across Forsyth and neighboring Dawson counties. Abijah told the governor that large swathes of land “will not be cultivated” because “labor now can not be found to hire...”

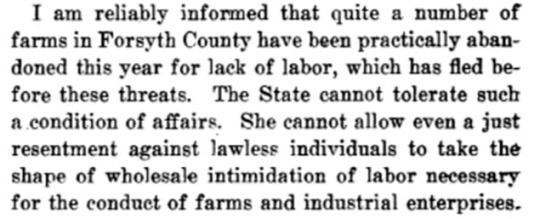

Gov. Joseph Mackey Brown referred to the situation Julian highlighted later in 1913, in a written message to members of the state senate:

After all, the governor continued, “there is no reason why farms should lose their productive power and why the white women of this State should be driven to the cook stoves and wash pots simply because certain people blindly strike down all of one class in retaliation for the nefarious deeds of individuals in that class.”

What happened in Forsyth was not unique. White people across the South had been pushing back against political and economic progress made by Black Americans after the end of slavery and would continue doing so.

In 1906, a white mob stormed downtown Atlanta, killing dozens of Black people and attacking Black businesses and homes. In 1921, a white mob destroyed a Black community in Tulsa, Oklahoma and, according to a government commission report, left nearly “10,000 innocent black citizens” homeless. The death toll was in the hundreds.

Once you begin to look, such violence stretches on and on, decade after decade.

Still hopeful that I might be able to somehow identify and locate living descendants of the people my family enslaved, I flew to Georgia last November.

‘Dick a Man, Lott a Woman’

While I was in Atlanta, I asked my mom and sister if they had time to talk about what I’d found. We sat one evening at the dining room table in my mother’s house, the same table on which we had once shared Thanksgiving dinners with Grandma Horseyfeather.

I had prepared two thick packets of documents that outlined our family tree, each with underlying records, to walk through the lineages of our slave-holding ancestors in three Georgia counties, including Forsyth.

I explained that my search began with a memory of walking with my mother’s father across some land our people used to own in Forsyth; and my grandfather casually remarking of the old well: “The slaves built that.”

“It added up from this one, just sort of little vague memory that I had of Brice gesturing at a well.”

The first question came from my sister, who is married to a Black man. Her voice was stretched thin with emotion. She asked: “Is there any possibility of doing the same for the people that our family enslaved?”

I’d found a man in Grandma Horseyfeather’s lineage who was a slaveholder and likely worked as an overseer in Jefferson County, Georgia. But neither I nor the genealogists we consulted could identify descendants of those he’d enslaved.

“So I’ve – I’ve tried,” I explained. “The issue is that the best details that we have are in Forsyth County, but in Forsyth County they forcibly expelled all of the Black people.”

There were, however, names of enslaved people who were bequeathed in the 1858 will of George Julian, Abijah’s father. At least two seemed to fit with a lineage I could trace.

Listed in the will as “Dick a man” and “Lott a woman,” they looked like a possible match for a couple living three households from Abijah Julian’s uncle in the 1870 census. Their names were listed as Richard Julian and Charlotte Julian. Was Dick short for Richard? And was Lott short for Charlotte?

I noticed that Richard Julian had an “M” in the column for Color. The M stood for Mulatto, someone of mixed race. Charlotte was 32 years old in 1870, an exact match for a 22-year-old enslaved woman listed on the 1860 slave schedule as belonging to George Julian’s widow. Richard was listed as 30 in 1870, which did not line up as neatly with an 18-year-old enslaved man next to Abijah Julian in the 1860 slave schedule.

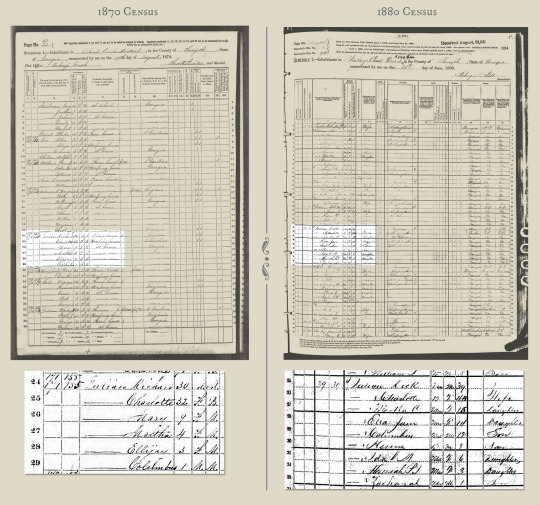

A comparison of the 1870 census and the 1880 census reinforces that Reuters journalist Tom Lasseter is following the same family from one decade to the next. (Source: Ancestry.com)

Still, based on the mention of the names Dick and Lott in George Julian’s will, I followed the Black family’s lineage from one census to the next.

In 1880, Richard was listed as Dick. Lott was there, too, as Charlotte. And their ages were close to what they should have been – about 10 years older than in 1870. The children listed in each census gave me confidence I was following the same family. In 1870, four children were listed. There were three girls and a boy. In 1880, the oldest child was no longer there; she would have been 19 or 20 and may have married. But the boy and the two other girls were there, names and ages matching. The Julians had added four children to the family since the previous census, too, the eldest 8.

My sister’s first question after I traced our family tree that night lingered: “Is there any possibility of doing the same for the people that our family enslaved?”

One of the children in the 1880 census would provide the path.

The Shacks

The day I arrived in Atlanta, November 1, I chatted with my mom about Forsyth and our family’s history there. She’d mentioned something that took me aback.

“When we were talking about the farm, you said there was a slave shack, a slave shed?” I asked her the next day. “What was that?

It turns out my mother had visited the Julian farm when she was a kid. Someone had pointed her to a pair of shacks on the farm and explained that they were where the families of the enslaved used to live.

“It was a structure – by the time we came along it was still on the property but it was, like, a wooden structure that was falling apart.” Her voice became low for a moment. “And that’s what we were told that it was. And I think – I don’t know.” She paused. “I know my grandmother talked about teaching people how to read, or people in her family having taught some of the slaves how to read.”

My mom, a slight woman with a calm voice who works as a nurse with organ transplant patients, was uncertain about the details. “I’m not sure what the – it was just information that she was sharing, maybe to make it feel better that they had slaves. I don’t know.”

I went to dinner with my mom at a Thai restaurant the following evening. I’d been in Forsyth that morning, looking at some documents about the Julian family. She asked me if I learned anything new. I told her about two murders in the family – a pair of sisters slain by the husband of one – that had been covered in the newspapers in the 1880s.

That’s not what she was asking about. My mom looked up from her tofu dish and said, “I am uncomfortable with how little attention was paid to what that was.”

Under her breath, she continued: “The shed.” She meant the slave sheds on the Julian farm.

She said nothing for a few moments. And then she explained, “I was 11.” It was her way of saying she was young at the time. What could she have known about such things? It was the same age as my eldest son.

Why was I putting this at her feet? I thought.

What did she have to do with a white man, dead now for a century, who got rich and enslaved Black people? Where was that money? Not in her pocket. She was working late shifts and driving a beat up Toyota with a side mirror attached to the car by duct tape.

But the feeling of indignation was mine. My mother, a child of the 1960s who took us to downtown Atlanta for parades on Martin Luther King Jr Day, wasn’t being defensive. She was trying to work through what it all meant.

An Unexpected Meeting

Just before Thanksgiving last year, I reached out to a young research assistant at the Atlanta History Center. I’d heard she was tracing descendants of people who fled Forsyth.

Over the phone, I told Sophia Dodd that I was looking for people with the last name Julian. She said she had someone in mind. But first, Dodd would need to check with the person; we arranged to meet in Atlanta later in the month. There was a possibility the person would join us, she said, “but I also know they’re in the midst of traveling so that’s a little up in the air right now.”

I met Dodd at her office a few days before Thanksgiving, ready to ask her questions about Forsyth County.

And then another woman walked into the Atlanta History Center: Elon Osby. She wore a cranberry-colored top and glasses with red cat-eye frames. The 72-year-old Black woman with gray hair shook my hand and said, yes, she would gladly take me up on a cup of coffee.

I hadn’t expected her. I’d not even known her name – Dodd had protected her privacy while Osby decided whether to meet me. But there Osby was, looking at me expectantly. The three of us headed to Dodd’s office.

Without my census forms in hand, I felt exposed. Those family history packets – the ones I shared with my mother and sister – were a way to guide the conversation. And this conversation was with a stranger whose history with my family may have involved slavery. I told Osby that I regretted not having materials to give her.

Osby looked me over. She got to the point. “Is it that you feel that your ancestors were slaveowners of mine?” she asked.

Because I hadn’t done a family tree for her, I explained, I couldn’t be certain. During months of examining the lineages of American politicians, we had held to a firm standard: a slave-owning ancestor needed to be a direct, lineal ancestor – a grandfather or grandmother preceded by a long series of greats, as in great-great-great-grandfather.

As I built my own family lineage, I knew that the Julians were slaveholders. But when I worked with the genealogists on our team to trace the enslaved people named in George Julian’s will, they urged caution. What wasn’t entirely clear: Exactly who had enslaved Richard and Charlotte? Was it George, or was it George’s brother, Bailey?

I offered Osby the abridged version. If she were a direct descendant of Richard and Charlotte Julian, “they were enslaved either by my direct ancestor, George H. Julian” – Abijah’s father – “or his brother.”

As I finished my sentence, I realized the distinction may have been important to the journalist in me. But in this context, it was meaningless. What mattered wasn’t in question: Someone in my family had enslaved hers.

Osby turned to Dodd, the young white woman who’d been helping her research her family.

“First of all, let me ask this.” Osby said. “Do any of these names that he mentioned ring a bell with what you’ve done?”

Dodd answered quickly. “Yes, so I think that it’s definitely very possible that Charlotte and Richard were enslaved by George,” she said.

I asked Dodd if she had an account with Ancestry.com and whether she could print some documents. Together, we navigated to the 1858 will for George H. Julian and the 1870 census forms that showed Richard and Charlotte Julian.

Osby had explained that her grandmother’s name was Ida Julian. And Ida Julian’s parents were Richard and Charlotte Julian of Forsyth County.

Ida. Daughter of Richard and Charlotte. I would see it later. Not in the 1870 census, because Ida hadn’t yet been born. But there she was, listed in the 1880 census. Ida Julian, age 6. Ida Julian, listed in the 1880 census as a young child. (Source: Ancestry.com)

I later found a marriage certificate showing that Ida Julian married a man named WM Bagley in 1889. She was young, perhaps 15. By 1910, the census showed them living in Forsyth County, the parents of three girls and a boy.

The youngest of their children, not yet a year old, was a girl recorded as Willie M. She would go by Willie Mae Bagley, get married, and become Willie Mae Butts – the mother of Elon Butts Osby. The former Ida Julian, now Ida Bagley, in the 1910 census. Her daughter, listed as Willie M., would become Elon Osby’s mother. (Source: Ancestry.com)

After we had worked through the small pile of papers that Dodd had printed, I asked Osby what it meant to see some of those documents.

“It makes people real now. It just makes all of this more real. And it has started a journey for me,” she said, adding that there’s “no telling where it’s going to go.”

I asked her what her family said about Forsyth County when they discussed it with her as a girl. “They didn’t. They didn’t talk about it,” she said.

It wasn’t until around 1980, when Osby was about 30 years old, that she heard her mother tell a reporter the story of her ancestors fleeing the county by wagon because white people were attacking Black families.

“There wasn’t any conversation about it,” Osby said. “But she did talk about her grandfather had this long hair, straight hair, and they would comb it.” That was Richard Julian, Osby’s great-grandfather, the man listed as a “Mulatto” on the 1870 census.

She paused and stared at my face for a moment.

‘I Don’t Think You Can Get Justice’

When Elon Osby’s grandmother, Ida Bagley, and her family fled Forsyth, they left behind at least 60 acres of land, she said.

They made their way to Atlanta after 1912, the year of the carnage. There, in 1929, her grandfather, William Bagley, bought six lots of land in a settlement of formerly enslaved people known as Macedonia Park, according to the local historical society.

It was located in Buckhead, long among the most expensive neighborhoods in Atlanta. The Black residents of Macedonia Park worked as maids and chauffeurs for white families in the area, as golf caddies and gardeners.

Osby’s grandfather made money as a cobbler and local merchant. Her parents opened a store and a rib shack. Her father was also a butler for a wealthy white family, her mother a cook. The area became known as Bagley Park, and her grandfather, according to a historical marker now at the site, was considered the settlement’s unofficial mayor. William Bagley, Elon Osby’s grandfather, was known as the mayor of Bagley Park, a Black enclave in Atlanta that was later razed by the county.

(Courtesy: Elon Osby)

In the late 1930s and early 1940s, nearby white residents – members of a women’s social group – petitioned the county to condemn and raze Bagley Park, ostensibly for sanitary reasons. It had no running water or sewer system. The county, which had not provided those services, agreed, forcing the families to leave. They were compensated for the land, but it’s not clear how much, and in the process they lost real estate in what is a particularly affluent quarter of the city.

Osby’s family had again been pushed off its land. The settlement was demolished and replaced by a park, later named for a local little league umpire. Last November, the city of Atlanta restored the area’s name: Bagley Park.

In thinking about Osby’s family and my family, I found it was impossible not to compare them – and the role slavery played in our respective paths. In 1860, Osby’s ancestors were enslaved and working the fields of Forsyth County. In 1860, my ancestor Adaline Julian, widow of George and mother of Abijah, reported a combined estate value of $19,020. She was among the wealthiest 10% percent of all American households on the census that year. And that wealth didn’t include her son’s holdings. Then just a teenager, Abijah had a personal estate of $4,828, according to census records. That amount lay largely in the value of the enslaved people bequeathed to him by his father.

In 1870, Osby’s ancestor, Richard Julian – free for only about five years – was listed on the census as a farmhand, with no real estate or personal estate to report.

In 1870, Abijah Julian – despite having “lost” those he had enslaved – still had a combined estate of $4,655. That put him in the top 15% of all households in America, census records show.

Osby said her parents used the money they got from the government after being forced out of Bagley Park to buy land in a different part of Atlanta. They continued to work hard. Her father was hired as an electrician by Lockheed, and her mother ran a daycare business.

Osby spent a career working in administration. She said she started as secretary for the manager of the city’s main Tiffany & Co location in 1969, then worked in various city government offices, and now for the Atlanta Housing Authority.

After she’d finished telling me about her family and herself, I asked Osby whether she would mind me recording some video with my cell phone. I asked once again about her family’s reluctance to discuss Forsyth. She repeated that Black parents had long kept such things quiet. I noticed she added the words “rape” and “lynchings.”

But, she said, she has seen considerable progress during her life. Osby, whose family was forced out of Forsyth in 1912, was the keynote speaker in 2021 at a dedication event in downtown Cumming, where a plaque memorializing the bloodshed in Forsyth had been installed. And Osby, whose family was forced with others to leave their neighborhood in Fulton County, is now a member of the Fulton County Reparations Task Force. The group advises the county board and has sponsored research on what happened at Bagley Park, including a report documenting what Osby already knew: that “property owners in Bagley Park were forced to liquidate their real estate, a vital link in the chain of generating generational wealth.”

“There was a time when I didn’t feel that restitution or reparations was necessary” for the land taken from Black families after 1912 in Forsyth, and then what followed in Bagley Park, Osby said.

“I just want somebody to acknowledge it and say, you know, we’re sorry. But I have come to realize, or come to feel, that we do need to receive something in the form of restitution. I think that the main thing is, if you touch people in their purses they’ll think before they let something like that happen again. I think it’s mainly about [how] we can never let this happen.”

As for her enslaved ancestors, Osby had a different outlook on reparations. “I don’t want to think of slaves as property. And if I have to give you a value for a slave person so that you can, you know, give me reparations for that – then that’s making them property. That’s reinforcing that idea that they were a piece of property for somebody to own.”

I asked her what it meant to know that history – to know more about what happened during slavery in such personal terms. To know that my own ancestors enslaved people. Osby puckered her bottom lip, paused for a moment and sighed.

She pointed her left index finger at me and said it was a question for me to answer. How did I feel, she asked, when I found out my ancestors enslaved people?

‘What Does It Mean to Know This?’

I told her the story of the old well and my grandfather. I told her about the reporting project, about finding out that my family enslaved people not only in Forsyth, but at least two other counties as well.

Finally, I stopped talking. In my mind, I had run through the right things to say. In a blur, I wondered: Should I apologize to Osby, to her family on behalf of mine?

Instead, I decided to talk about what made me most comfortable: the journalism itself. “A lot of it has been just establishing, sort of, the facts – figuring out, this is who they were, this is what happened,” I said. “I guess sitting here right now I don’t have an answer for – I don’t have an answer for my question” on the value of discovering more about slavery.

She leaned back and laughed.

At some point, I lowered the camera from chin height to the table. My hands were trembling. I was based in Iraq for three years. I sat with militants in Afghanistan. I know what mortar and machine gun fire sound like, at very close range. But at this little table, before this woman, I felt nervous.

I kept talking. I talked about how we – meaning white people – choose to know but not know. I told her about my mom remembering the decrepit former slave sheds on the Julian farm.

Osby no longer was smiling.

She began to talk about something that circled back to her comments about her great-grandfather’s straight hair, her curiosity about possible Cherokee Indian heritage. And, also, to rape.

“Black people, we’ve always known either through the movies or if you’ve learned it, you know, from your family, about the interracial relationships that happened on these plantations or whatever,” she said. “My grandmother – very, very fair skinned. I have one picture of her where she, you know, looks like she’s white. And so, you know that somebody else was there. You know?”

Somebody else was there. It was a phrase with a passive structure common to the South, a way of not assigning blame to the person sitting across the small table from you in the corner of an office. The meaning nonetheless seemed clear to me: Did my ancestor rape her ancestor?

“I’m curious, and that’s one reason why I was excited about coming to speak with you because I want to find out about the Cherokee part,” she said. “And also, if there was a white person, you know, that was, her – whatever,” she said, cutting the sentence short and fluttering her hands in the air.

I told her that I’d done a DNA test online. She said she was considering taking one as well.

After we spoke, Osby asked me to go with her to the graveyard at Bagley Park. I followed her Mazda. Its license plate read MS ELON. Her grandparents were buried there, she said, but she couldn’t say where. The gravestones had been vandalized over the years, Osby explained, looking at the broken markers.

Panic and Questions

After we parted, I drove to Forsyth County and the Julian farm. I could see across the road to the spot where my mother described the slave shacks having once stood.

The door was locked, the farmhouse empty. I stood outside the white clapboard home and stared. The leaves crunched underfoot, down at the end of Julian Farm Road. I rested my forearms on a dark slat fence and scanned the property, a utility shed to the right and a patio to the left.

I did not see the well.

I walked to the front of the house and looked for it. The well wasn’t there. I went to the back edge of the land, which now sits on the shore of a man-made lake that flooded part of what was once Abijah Julian’s farm. Nothing. The waters of Lake Sidney Lanier near what was once a farm owned by Abijah Julian. The lake, created in the 1950s, flooded parts of that farm. REUTERS/Tom Lasseter

I felt panicky. The well, the totem of my memory and the genesis of this project – “The slaves built that” – was nowhere. Was it possible I had mixed up some other memory, that it was never at the Julian farm?

I walked over to a step behind the house and sat down. My thoughts about the well gave way to replaying parts of my meeting with Elon.

Should I have apologized to her? “I am sorry,” I could’ve said. “I am sorry that my ancestors brutalized your ancestors.” What had stopped me?

The next day, I sent a text message to the man who now owns the Julian property. Did he know anything about an old well? “Yeah, there was a well next to the house that was dried up. We covered it,” he replied. He sent me a photograph of the front of the house from a 2019 real estate listing. And there it was – the well I remembered, at the far right of the picture.

I peered at the photo. I read the listing. The lake that flooded part of the farmland had created 209 feet of waterfront that now featured four boat slips, according to the advertisement for the property. It noted the farmhouse was “originally built in the late 1800’s by the family of State Senator Abijah John Julian” and added another dash of history: the Julian family was “of the Webster line circa 1590 England.” There wasn’t a word about the other side of the Julian family history: slavery.

Instead, under the section for what the seller loved about the home, was this line: “Your own private plantation.”

What Should Be Handed Down?

In the months after my visit to Forsyth, I’ve looked at a video of the church service that I attended last summer on Juneteenth, the national holiday marking the end of slavery. At the time, I had bristled at the pastor’s remarks, which centered on the need for white people to face our history, to atone.

Toward the beginning of the service, the children had been sent to Sunday school. So my sons weren’t sitting next to me when the pastor said, “We’re asked to stay home and to reflect with those who we know and whom we love – we’re asked to … have the difficult conversations about race and status and prestige and wealth.”

There was another detail that I hadn’t associated with that day’s sermon. It wasn’t only Juneteenth; it also was Father’s Day. From a 2019 real estate listing. The well is seen at the far right in this photo of the front of Abijah Julian’s house.

I’ve thought more than once about all that I had missed. About what to tell my children about everything I’ve learned in the past year. About our family’s part in slavery and the descendants of those we enslaved. About my conversation with Elon Osby.

What should be handed down, and what should not?

Getting ready for a reporting trip last year, I was sifting through online documents from an archive in south Georgia.

I came across a photograph from 1930 of white men sitting in front of an American Legion post. They each wore a medal on the left lapels of their suit jackets. I zoomed in and saw what had caught my eye. It was the cross of military service, handed out by the United Daughters of the Confederacy to World War I veterans who were direct descendants of Confederate soldiers.

In a little white box on a shelf in my home office, I have that same cross. It had been given to my great-grandfather, from Brooks County. After my great-grandmother Horseyfeather died, my family gave it to me, the ever-faithful son.

I fished the cross from its box and turned the thing around in my fingers. The cross was decorated with an X formed by two stripes of stars immediately recognizable from the Confederate battle flag. Around the edge, in the background, are a Latin phrase and two dates: Fortes Creantur Fortibus 1861-1865. The years are those of the Civil War. I Googled the phrase. It means the strong are born from the strong.

I’d had that cross for about 25 years and always associated it with my great-grandfather’s service in World War I, its dates marked in the foreground. I had never stopped to look more closely.

Peering down at it now, I realize it also meant something more: a loyalty to the South when it was a land of slavery and secession.

I was holding on to a relic of the Lost Cause, a history of savagery cloaked in nostalgia. I was holding on to something that I needed to explain to my sons, and then to let go. As I type these words, I have yet to have that conversation. The medal remains on my shelf.

Apology and Absolution

I met with Elon Osby once more earlier this month. We walked again through the cemetery at Bagley Park, where somewhere her ancestors are buried, their gravestones long gone. We stopped at a picnic table. I asked her about the last time we met, reading some of our quotes out loud and talking through what each of us had meant.

There was rain coming, with dark clouds, then lightning. I told her that I’d been nervous during our initial conversation. She asked whether I thought the guilt had been passed down: “Most white people do not have ancestors that owned slaves,” she said. I pointed out that I have at least five.

I said that I’d wondered if I should have apologized. “No,” she said, “I don’t transfer the guilt. Or not the guilt, but the responsibility of it. I don’t do that.” I said with a nervous laugh that I wasn’t asking her to absolve me.

The lightning drew closer. It was time to leave. “We’ve probably covered everything,” Osby said, gesturing to get up.

But I wanted to say more. Ignoring the rain, I reached for the words I hadn’t found during our first meeting: “I’m very sorry that it happened. You know, that all of that happened. And I feel that every time I look through those wills and the language that they used. And that 1858 will – listing furniture and livestock and then human beings. You know, I can’t help but be sorry.”

Osby stopped and looked at me. Listening to the recording later, I could hear the wind and the rain in the background. And then her voice. “It doesn’t feel good at all when you see the horses and cows and slaves. You know, it doesn’t feel good at all,” she said. “But at the same time, it happened. It happened to my people. I don’t want to forget about it.”

She pointed at the packet of genealogical material I’d brought along, mapping our families and that terrible history long ago in Georgia. “This is good enough. What you’re doing for me and my family, bringing this information to me.”

She let a moment pass, and then said: “You’re absolved.” She threw her head back and let the laughter roll like thunder. As the rain fell, we walked to the parking lot together. We paused, then hugged before parting.

“The Slaves Built That”’

By Tom Lasseter

#georgia#slavery#slave records#reuters reporter explores his slave owning roots#“The Slaves Built That”#white supremacy#Blacks Enslaved in America#forsyth county#lynching#stolen land#stolen heritage#ancestral dna

5 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Due Date (Todd Phillips, 2010)

Bolling Bridge / Boling Bridge / The Big Green Bridge (Demolished)

Forsyth County, Georgia - Hall County, Georgia (USA)

Bridge over the Chestatee river (Lake Lanier)

Type: truss bridge.

#due date#todd phillips#2010#bolling bridge#boling bridge#the big green bridge#forsyth county#hall county#Georgia#USA#chestatee river#lake lanier#truss bridge#bridge

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Welcoming the new year.

1 note

·

View note

Text

Appeal Property Taxes | Forsyth County

Is your property appraisal higher in Forsyth County? Consider protesting with O'Connor this year. To know more visit https://www.cutmytaxes.com/georgia/forsyth-county-property-tax-reduction/

0 notes

Text

Forsyth County leaders should be ashamed for the taxpayer-friendly changes put into the NHL proposal

Last year, a new developer, Vernon Krause, began openly talking about bringing the NHL back to Atlanta for the third time. In his vision, there would be a new 20,000-seat arena and a $2 billion “mixed-use development featuring hotels, retail, residential components”. The name of this area would be called the “Gathering at South Forsyth”.

After constructing the arena, the following would occur:

1…

View On WordPress

#Atlanta#Atlanta Business Journal#Binding Agreement#Board Of Commissioners#County Commission#Economic Driver#Forsyth County#Gathering at South Forsyth#Georgia#Hotel Tax#Krause Sports and Entertainment#NHL#Property Tax#Real Estate Taxes#Vernon Krause

0 notes

Text

Lilburn, Georgia's Michael Kinser arrested in Forsyth County; Did he repeat his 2014 crimes in Florida?

Michael Peter Kinser, 29, of Lilburn, Gwinnett County, Georgia, United States was required to register as a sex offender in Florida, USA. On January 14, 2014, he was found guilty of traveling to meet a minor for the purpose of sexual conduct in Florida.

Recently, Kinser was arrested during the Operation Masquerade in Forsyth County, Georgia. It was a multiagency probe into internet crimes…

View On WordPress

1 note

·

View note

Text

Batman Researcher Will Say Gay

A Batman researcher was asked not to mention a gay man in a lecture to school children. Instead, he canceled his talks.

Marc Tyler Nobleman is an author who writes fiction and nonfiction mostly for children and teenagers. In 2012, he published a biography called “Bill the Boy Wonder,” about Bill Finger, who was an anonymous co-writer with Bob Kane in the creation of Batman and Gotham City. That…

View On WordPress

#batman#bill finger#don&039;t say gay#forsyth county#georgia#homophobia#marc tyler nobleman#sharon elementary school

0 notes

Text

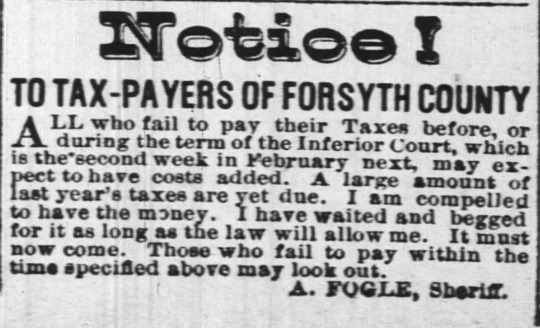

"Notice! To Tax-payers of Forsyth County," The Winston Leader (Winston-Salem, NC), January 31, 1882, accessed July 1, 2022, https://www.newspapers.com/image/67586544.

#taxpayers#forsyth county#historical advertisements#winston-salem#north carolina#nineteenth century#19th century

1 note

·

View note

Text

But one lesser-known fact is the lake sits on top of the Black-town, Oscarville.

Oscarville was burnt down in 1912 and more than a thousand residents were forced to flee following the allegations of rape.

Rob Edwards was arrested in September 1912 along with Earnest Knox and Oscar Daniel, both teenagers, all accused of raping and murdering a young white woman named Mae Crow.

Edwards was dragged out of jail, beaten with a crowbar, and then lynched from a telephone pole.

Daniel and Knox went to trial and were found guilty on the same day. The boys were sentenced to death by hanging.

After the trials and executions, white men, known as Night Riders, forced Black families out of their homes by bringing their land, churches, and schools.

Once Black families fled, Lake Lanier was built on top of what was burned down.

2.Kowaliga (Benson), Alabama

Turns out, Alabama’s Lake Martin is built on the previous majority-Black town of Kowaliga. It is home to the first Black-owned railroad started by William E. Benson and the Black school Kowaligia Academic & Industrial Institute.

William is the son of John Benson, who was enslaved and then freed. He went on a journey to rescue his sister in Florida, who was separated during slavery, and they made their way back to Alabama. John purchased thousands of acres of land sold to Black families, where he formed a community.

William helped his dad expand the family business.

After William’s death and the closing of the school, Kowaligia was destroyed to make room for Lake Martin.

3. Seneca Village In New York City

Seneca Village began in 1825 and, at its peak, spanned from 82nd Street to 89th Street along what is now the western edge of Central Park in New York City.

By the 1840s, half of the African Americans who lived there owned their own property, a rate five times higher than the city average, as reported in Timeline.

In 1857, Seneca Village was torn down for the construction of Central Park. The only thing that remains is a commemorative plaque, dedicated in 2001 to the lost village.

4. Susannah, Alabama

Susannah, or Sousana, was also flooded by Lake Martin.

According to Alabama Living, more than 900 bodies were moved from cemeteries before the land was submerged.

The town once included a gold mine, a school, two mercantile, a grist mill, a flour mill, a sawmill, a blacksmith shop, and a church.

5. Vanport, Oregon

In the 1940s, Vanport was the center of a booming shipyard industry because of World War II and quickly became the second-largest city in the state.

But as World War II saw white males drafted to serve overseas, a labor shortage pulled in a great migration of Blacks from the south.

With soldiers being drafted overseas to fight in the war, Oregon saw a labor shortage. This resulted in a great migration of Black Americans from the south.

These new workers needed places to live, as the Albina neighborhood was the only place where Black people could live legally. It became too small for the growing population of Black Americans, and Vanport was built as a temporary housing solution.

At its peak, 40,000 residents, or 40 percent, were African-American.

But then, in 1948 massive flooding erupted in the neighborhood, and city officials didn’t warn residents of the dangerously high water levels, Many didn’t evacuate in time.

The town was wiped out within a day. 18,500 families were displaced, more than a third Black American.

Today, that area is known as Delta Park.

youtube

#5 Black American Towns Hidden Under Lakes And Ultimately From History Books#Black Towns#Black Towns flooded by white supremacists#Lake Lanier#Lakes over Black Communities#Amber Ruffin#forsyth county georgia#georgia#alabama#Youtube

13 notes

·

View notes

Text

.

#given the opportunity I would go back to school to study black history because holy shit#was looking into some things I've wanted to learn more about and oh boy am I learning#Ota Benga and the Tulsa Massacre and the Tuskegee syphilis experiments#not to mention the shit my family was directly effected by#the racial cleansing of Forsyth County#delete later

30 notes

·

View notes

Text

Monroe County Fire Department, GA

#larry shapiro#larryshapiroblog.com#shapirophotography.net#larryshapiro#larryshapiro.tumblr.com#fire truck#firetruck#fire engine#HME#1871#pumper#Monroe County FD#MonroeCountyFD#Forsythe GA

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Paying Too Much on Property Taxes?

Are you paying too much on Forsyth County property taxes? Wondering how most people overpay property taxes and how to avoid doing so in the future.. O'Connor can help you, reach us at https://www.cutmytaxes.com/georgia/forsyth-county-property-tax-reduction/

0 notes