#francis parkman

Text

Last spring, 1846, was a busy season in the city of St. Louis. Not only were emigrants from every part of the country preparing for the journey to Oregon and California, but an unusual number of traders were making ready their wagons and outfits for Santa Fe. The hotels were crowded, and the gunsmiths and saddlers were kept constantly at work in providing arms and equipments for the different parties of travellers. Steamboats were leaving the levee and passing up the Missouri, crowded with passengers on their way to the frontier.

Francis Parkman, The Oregon Trail, 1949 edition

0 notes

Text

ROLEPLAY HISTORY!

The rules are simple! Post characters you’d like to roleplay as, have roleplayed as, and might bring back. Then tag ten people to do the same (if you can’t think of ten, just write down however many you can and tag that number of people). Please repost, don’t reblog!

CURRENT MUSE(S): (canon muses)

mat cauthon ( the wheel of time )

quinn blackwood ( the vampire chronicles)

michael curry ( the mayfair witches )

adolin kholin ( stormlight archive )

jasnah kholin ( stormlight archive )

syl ( stormlight archive )

vin venture ( mistborn )

ivar the boneless ( vikings )

bellamy blake ( the 100 )

francis de valois ( reign )

cahir ( the witcher saga )

aviendha ( the wheel of time )

min farshaw ( the wheel of time )

paul atredies ( dune )

alia atredies ( dune )

carl grimes ( the walking dead )

aramis ( the three musketeers )

john silver ( black sails )

seth gecko ( from dusk til dawn : the series )

will graham ( hannibal )

rodrigo borgia ( the borgias )

lucrezia borgia ( the borgias )

michael grey ( peaky blinders )

marcel gerard ( the orignals )

anakin skywalker ( star wars )

louis xiv ( versailles )

moiraine damodred ( the wheel of time )

lan mandragoran ( the wheel of time )

and four ocs !

WANT TO WRITE: (maybe i will write them someday, maybe not)

like idk right now? probably none. i considered adding marius from the vampire chronicles but decided against it lol

HAVE WRITTEN:

peter petrelli ( heroes )

jaime lannister ( asoiaf )

theon greyjoy ( asoiaf )

sam "falcon" wilson ( mcu )

raven / mystique ( mcu )

elijah mikaelson ( the the originals )

caroline forbes ( the vampire diaries )

enzo st. john ( the vampire diaries )

elle bishop ( heroes )

arthur petrelli ( heroes )

genevieve ( the orginals )

aurora ( the originals )

matt parkman ( heroes )

kaz brekker ( six of crows )

the darkling ( shadow and bone )

fergus fraser ( outlander )

sarah manning ( orphan black )

james patrick march ( ahs )

tate langdon ( ahs )

jimmy darling ( ahs )

kit walker ( ahs )

ethan chandler ( penny dreadful )

lazlo kreizler ( the alienist )

marcus isaacson ( the alienist )

lucius vorenus ( rome )

dwight enys ( poldark )

nell crain ( the haunting of hill house )

charles xavier ( mcu )

elizabeth of york

gendry ( asoiaf )

dinah madani ( the punisher )

freya mikaelson ( the originals )

carolina villanueva ( high seas )

nicolas sala ( high seas )

WOULD WRITE AGAIN:

not sure who i would ? write again ? sometimes i'm like hey maybe but then i'm like nah i don't want to lol

Tagged by: @stcrforged

tagging : @caracarnn - @xhideyourfires - @adversitybloomed - @wstfl - @honorhearted - @godresembled - @bas0rexias - @indigodreames and anyone else?

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Devil in New France: Jesuit Demonology, 1611–50

Goddard, Peter A

Ce divin employ de Missionnaire devoit renverser la tyrannie des demons.(f.1)

The Jesuit missionary Paul Le Jeune described New France as the 'Empire of Satan.' His colleague Jean de Brebeuf called the Huron country the 'Devil's kingdom,' while Jerome Lalemant referred to the Huron themselves as 'slaves of the Devil.' The pioneer missionary Pierre Biard suggested that the sauvages of Canada had some idea of God, 'but they are so perverted by false ideas and by custom, that they really worship the Devil.'(f.2) Others speculated that the Devil animated shamanic activity and meddled in dreams, thereby controlling these unfortunate peoples. In Relations addressed to the faithful in France, the Devil appears as the formidable enemy of the French Jesuits' most important seventeenth - century mission.(f.3)

Accepting these declarations, modern scholars attribute to these Jesuits an active diabolism, or belief in the real presence of the Devil among the Algonquian and Iroquoian peoples. Credulity about Jesuit diabolism is upheld by Bruce Trigger, who asserts that 'the Jesuits ardently believed in the power of Satan and his attendant devils.' Karen Anderson argues that 'the Jesuits were convinced that the native people of New France were truly a fertile ground for the Demon.' William Eccles, in a standard textbook account, suggests that 'the Jesuits at first regarded the religious beliefs of all the Indians as the work of Satan, and every setback was attributed to his efforts.' J. Baird Callicott, who gives voice to the opinion that missionary records are 'so hopelessly abject as to be more entertaining than illuminating,' claims also that Europeans believed aboriginal peoples to be 'mindfully servants of Satan.' These modern and postmodern commentators all appear to follow the lead of Francis Parkman, who in The Jesuits in North America (1867) stated that demonic resistance to their mission was 'an unfailing consolation to the priests.'(f.4)

This apparent consensus among historians of early modern Canada should not surprise us. An active diabolism, and its attendant demonology (the study of devilish phenomena), is consistent with the thorough - going religiosity that characterized the missionary mind during that 'golden age of the Devil.'(f.5) In its classic form, which posited the reality of the Devil and diabolical agency in the world, such demonology should have been nowhere more secure than among the Jesuits. After all, their Spiritual Exercises upheld the belief in Satan. The Meditation of the Two Standards asserted that 'the field of battle is that of the kingdom of Christ versus that of the Devil':(f.6) that is what Jesuits would find in New France.

However, historians and anthropologists have been reluctant to probe past the pervasive military metaphor in early modern Jesuit discourse,(f.7) or to engage French Jesuit mentality as it evolved beyond sixteenth - century origins.(f.8) Instead, they have taken the Relations at face value, and have been content to assume that Jesuits were obsessed by the Devil and saw his hand everywhere. For today's scholar, the attribution of a belief in diabolical conspiracy is useful for stereotyping the missionary as a prisoner of mental horizons that left him unable to understand the alterity of native life and isolated from intellectual change in early modern France. It shows the distance, presumably, between the enlightened and secularized outlook we share, and that of the dark days of early colonialism.

The question of Jesuit demonology deserves re - examination in light of recent interest in the history of the concept(f.9) and our growing awareness of the role of the Society of Jesus in intellectual and cultural change in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. This article assesses Jesuit demonology in New France from 1611 to 1650, a time during which Jesuits dominated missionary activity in the fledgling colony. It argues that in contrast to the stereotype upheld by most historians and anthropologists today, early modern Jesuit demonology was characterized by doubt and caution. According to French Jesuits, the Devil occupied a highly circumscribed place in the encounter between native and European. The arch - adversary of Christianity is prominent in some Relations (1632 - 72), where his appearance often helped to explain drastic reverse or tenacious resistance to the missionary program. Representations of the Devil were deployed as part of the early modern pastorale de la peur, or 'pedagogy of fear': diabolical images were invoked to induce salutary fright in the native audience. Occasionally, mysterious phenomena were attributed to diabolical intervention, and a missionary might find himself exorcising demons from an aboriginal host.'(f.10) Yet diabolism was not usually cited as a factor that explained the success or failure of conversion, and the Devil was not held responsible for the spiritual condition of these peoples.

Instead, French Jesuits explained native life and religious experience largely independently of demonology, and without reference to the supernatural. In situations that can be reconstructed on the basis of the Relations and mission correspondence,(f.11) Jesuits tended to refute the claim that the Devil was actually present in native life. In place of the 'positive obsession with the devil's physical presence in the world' that abounded in the seventeenth century,(f.12) French Jesuits, including Paul Le Jeune, Jean de Brebeuf, and Paul Ragueneau, the dominant figures in the Canadian mission up to 1650, developed an analysis of native life which stressed the historical and cultural backwardness of these peoples, and which emphasized the illusory and fraudulent nature of the native claims about the supernatural. Other Jesuits, including Jerome Lalemant in the Huron country in the 1640s, continued to argue that the Devil was directly responsible for native recalcitrance. This opinion was marginalized, however: by 1650, a clearly sceptical viewpoint dominated among the missionaries in New France. Such incredulity, while rooted in scholastic disdain for popular magic, indicates the tilt towards rationalism and relativism, and the Cartesian separation of the material from the spiritual world which is noted among secular elites by the middle of the seventeenth century.(f.13)

What characterized Catholic diabolism in the early modern period? Since the fourteenth century, belief in the real presence of the Devil had been growing in Latin Christendom. Theologians in the late Middle Ages argued that, far from being an orderly place, the universe was characterized by God's arbitrary action and diabolical counteraction.(f.14) The growing rigidity of Western Christianity's moral code, as the decalogue replaced the traditional and more flexible inventory of the seven sins, increased the Devil's sphere of responsibility over individual deviance.(f.15) In place of the optimistic view that pagan belief and folk superstition were simply misguided attempts to invoke supernatural succour, many theologians found idolatry.(f.16) In the sixteenth - century Reformation era, 'superstition,' like witchcraft, graduated from limited maleficence to a more deadly status as literal service to the master of hatred and pollution.

In New Spain, which served as the model and exemplar of missionary enterprise in the early modern world, initial optimism about the prospects for conversion was followed by growing conviction of the magnitude of diabolical resistance to Christianity.(f.17) First - generation Spanish observers as diverse as Hernan Cortez and Bartolome de Las Casas argued that American religion was nothing more than misguided spiritual feeling, and that it would be transformed into Christianity when instruction banished religious ignorance. But as the spiritual conquest of the New World ground to a halt, diabolism, or cultic resistance orchestrated by Satan himself, emerged as an explanation for the lack of progress. The sophisticated institutions of Inca and Aztec religion were reinterpreted as diabolical rites rather than as inefficacious superstition.(f.18) Spanish Franciscans and Jesuits alike regarded native revolts as the work of the Devil.(f.19) Jose de Acosta, writing in 1590, suggested that the Devil had his Rome in Tenochtitlan and his Jerusalem in Cuzco. Acosta spoke of an elaborate system of diabolical observance that encompassed the ritual behaviour of even the most remote Chichimeque or former Incan vassals in the Andean backwaters.(f.20)

This rich demonology had well - known French exponents, including Jean Bodin and Pierre de Lancre.(f.21) De Lancre, the infamous witch hunter of the pays of Labourd in southwestern France in 1609, was particularly influenced by Acosta. According to de Lancre, the Labourd's superabundance of witches was a result of missionary success in the New World and Japan: demons had fled those parts by ship, to take up residence in his own remote region.(f.22) In France, especially in the peripheral regions, contemporaries noted an apparently widespread belief in diabolical witchcraft. This belief was accompanied by panics, trials, and exorcisms at every level of society It is not surprising then, that such beliefs were transported to New France, or were upheld by French Jesuits themselves.

Just as Satan played an important role in historical Christianity, as the embodiment of evil and the adversary who defined the truth,(f.23) so he was integral to early modern Jesuit self - formation. To Ignatius Loyola, he was a hostile and aggressive competitor, ceaselessly testing Christian virtue. In the Ignatian outlook,

the enemy is clearly known and identified. He is the devil, the tempter of men, who uses every device, exploits every weakness, and loses no opportunity to attack and destroy the souls of men. No man is secure from his ambushes. His subtlety and tricker,v are such that he often deceives men into doing evil in the name of good. He is a liar and a murderer, as he has been from the very first. Constant vigilance is mandatory, therefore, along with an unwavering resolution to do the opposite of what the evil one proposes.(f.24)

Missionaries secured their spiritual battle hardiness through contemplation of combat under the the standard of Christ.(f.25) The Devil was a reminder of their superior vocation, and he could be imaginatively evoked in any situation.(f.26) Jesuits in New France carried this personal sense of the Devil as a constant check in all their actions.

Yet, reflecting pre - Reformation piety that had 'humanized' the Devil, and an educated humanism that promoted scepticism towards folk custom and belief, Jesuits often made him a figure of mockery and contempt rather than a terrifying objective enemy or the locus of an opposite, evil religion.(f.27) This Devil was more the symptom than the cause of human disorder. The humanist conception of the Devil was poorly reconcilable with the 'diabolization,' the polarization of religion into Godly and diabolical camps in early modern Catholic theology.(f.28) French Jesuits did not adopt their confrere Jose de Acosta's demonology or repeat Delancre's facile diabolism. Generally, they were wary of enthusiastic expressions of demonology that appeared in the early seventeenth century.

In part, this scepticism reflected the Jesuits' orthodox theology, the via antiqua that had been revived by Francisco Suarez in the later part of the sixteenth century. The neo - scholastic outlook promoted the idea of an orderly natural world with limited scope for the demonic. Following Thomas Aquinas, it suggested that no nature was so forlorn that God was not present.(f.29) At the same time, reflecting the domestic scene in the early seventeenth century, French Jesuits evinced an obsession with sin, a tendency shared with other religious parties including Oratorians and the later Jansenists.(f.30) The preoccupation with the failings of nature and the absolute necessity of grace occluded the Devil as an independent actor of consequence. His agency might animate the resistance of human nature, but in a sin - filled world, sinful nature and not devil worship was the deviance of greatest concern.(f.31) The gloomiest commentators in this seventeenth - century tradition fused diabolism and sin to create 'moral paganism,'(f.32) but for contemporary Jesuit theologians the discussion of sin, its origins and its consequences, was sufficient; there was more than enough to say about human depravity without dragging the Devil into the picture.(f.33)

In France, Jesuit diabolism was further qualified by prudence, political and otherwise. In 1599, during the Society's exile from France, the case in Paris of the 'demonisme pretendu' of Marthe Brossier(f.34) created a scandal. Leaguer rebels used her exorcism to criticize Henri IV by likening him to the Devil. The king subsequently outlawed public exorcisms, as authorities grew alert to the subversive potential of demonism.(f.35) Concerned to demonstrate allegiance to the crown, Jesuits were subsequently reluctant to pronounce on cases of diabolical activity, including witchcraft. The case of alleged diabolism at Loudun in 1643 is often cited to support claims of Jesuit credulity.(f.36) Jean - Joseph Surin exorcized Jeanne des Anges and her sisters, and found that not only were the nuns possessed but so was he! Yet Surin himself was unrepresentative of his order's demonology: his colleagues saw him as 'a genuine case of mental derangement.'(f.37) The less credulous demonology of the German Jesuit Friedrich von Spee,(f.38) which stressed the fraudulent nature of alleged witchcraft and cautioned against the too easy belief in the Devil, better reflects increased scepticism within the Society.(f.39)

By the early seventeenth century, other Catholics may have been growing wary of diabological enthusiasm. Study of the process of saint - making in the early modern Catholic world reveals that authorities elevated the burden of proof in cases of the miraculous: 'the supernatural was defined, graded and labelled with increasing care.'(f.40) Inquiry had to be thorough and resistant to the scepticism of Protestants and libertines, not to mention the derision of their polemics. Emphasis on order in the post - Tridentine Church further militated against the too quick evocation of the Devil. The diabolical retained its place in the hyperbolic sermons of Francois de Toulouse, who described sinners as 'diables incarnez.'(f.41) But one did not hear that kind of talk in elite circles, from which Jesuits were recruited. Nor did it appear in specialized theological treatises. Indeed, the seventeenth - century discourse of Hell, to which the Devil belonged, has been fairly characterized as exoteric: it was meant for public consumption, an aid to the disciplining of the flock, but it was not central to esoteric belief.(f.42) In France, scepticism about diabolism demonstrated, and contributed to, a growing elite condescension of 'la sotte credulite du peuple.'(f.43)

Concern to test claims about the supernatural may also reflect a revival of curiosity about nature, a trend visible on both sides of the confessional divide. The study of natural phenomena became more legitimate in the early modern period, as theological strictures were undermined by a positive valuation of curiosity.(f.44) Strongly Aristotelian in their concern to depict natural laws and natural causation, Jesuits were critical of magic, which invoked angels and demons in explaining natural events.(f.45) With their scholastic training, French Jesuits were able to integrate the rationalism and empiricism of the new learning.(f.46) The early missionaries to New France were not trained in natural philosophy, but they were matter of fact and empirical rather than wonder - struck in their descriptions of the land and its peoples. They preferred the reports of eye - witnesses to hearsay, and questioned their informants intently. Evidence of this shift towards empiricism occurs among Spanish Jesuits as well, as hose de Acosta investigated geoenvironmental influences and launched an inquiry into the sources of aboriginal myth,(f.47) even while he described their religion as Devil worship. A need to investigate natural causes formed a growing part of Jesuit ideology.(f.48)

The position of missionaries in New France itself also contributed to the shift from credulity to scepticism. In New Spain, the church enjoyed a position of great authority. The Conquista involved the clear superimposition of Iberian social hierarchy; the clergy were a 'first estate' in Mexico or Peru as in Castile. Their 'spiritual conquest' entailed privilege as well as responsibility. In contrast, New France supported a modest number of missionaries (three in 1632, only fifty or so by mid - century), tenuous habitation, total absence of conquest, and only a limited superimposition of France on native society. In 1634 Paul Le Jeune wrote wistfully of the 'great show of power' by the Portuguese in the West Indies. This display had so intimidated aboriginal peoples that they 'embraced, without any contradiction, the belief of those whom they admired.'(f.49) In New France, in contrast, missionaries were hostages of the fur trade and of military alliance: they could not assume dominion. Canada was notable for its physical, social, and spiritual isolation, and for the vulnerability of its settlements. Most French people did not want to go there, and government officials did not care.(f.50)

This absence of conquest, and the corresponding lack of leverage over native peoples, forced the Jesuits to more conservative modes of inquiry. With the exception of their extravagant hopes for the mission to the Huron peoples before 1648, Jesuits were not optimistic about the possibilities for conversion, and, in any case, they were nearly always disappointed. They saw Canada as a testing place more than a theatre of spiritual conquest.(f.51) Seventeenth - century missionary accounts contain a wealth of ethnological data, but no sense of an overarching unity that made native society cohere in opposition to Christianity, and few swaggering claims about the epic scale of the missionary project. After the failure of the mission to the Hurons in 1649, New France would become known as a land of martyrdom, rather than a 'Christian republic' like that of the mission reduccions in contemporary Paraguay.(f.52)

At the same time, the void of French civilization offered unprecedented opportunity for contact with untamed human nature. Missionaries were exposed not to an esoteric religion of the natives (as was fed to such acute commentators as Bernardino de Sahagun by willing caciques),(f.53) but to their daily material grind. Missionaries found themselves in physically close, dependent situations, struggling with language and working hard to overcome aesthetic revulsion. The barrier to conversion appeared to be native living habits rather than their religious practices. The great Spanish commentators, members of a ruling class with a Hispanicized, bilingual servant class to succour their needs, never enjoyed this vantage point.

Unlike the Spanish diabolists, then, French Jesuits were less likely to encounter a demonic conspiracy that animated resistance to their project or provided the natives with a rival religion. The Devil, while gracing the printed page as a terrible menace, was in the mission fields a nuisance of a lesser sort. This attenuated demonology appears in the Jesuit Relations and in correspondence available in Monumenta Novae Francia. It can be studied in the references to the diable, the demon, or most often demons, diabolical entities lower on the scale, as well as the occasional mention Df the prominent Manitou, and various other Genii, Aoutem, Oki, and Iroquoian 'False - faces.' Together, the accounts of these phenomena produce a portrait of a Devil who, if not absent, is distinctly less prominent than we might expect. He conforms to a version of the diabolical that features the illusory, the fraudulent, and the error - ridden, and is marginal rather than central in religious life.

In his Relation of 1634, Paul Le Jeune noted among the virtues of the Algonquians their poverty and their material simplicity. Repeating the medieval Christian association of riches and the propensity to evil, he wrote that there was 'not one who gives himself to the Devil to acquire wealth.'(f.54) This he contrasted with the luxury and decadence of France, where contemporary confessional manuals devoted increasing emphasis to greed and avarice.(f.55) The natives were too poor to be tempted in this direction. Just as it would not take many years to learn their arts,(f.56) the Devil would find little opportunity among them. He might, Jesuits allowed, be more active among the Huron: these Iroquoians were a sedentary, agricultural, and relatively prosperous people, some of whose superstitious practices resembled those of rustic Europe itself. Boasting 'neither Temples, nor Priests, nor Feasts, nor any ceremonies,'(f.57) however, Huron possessed few likely structures for the formal worship of the Devil. They were spiritually undeveloped, compared with other peoples.

The missionaries were inclined, through studies of classical literature and shared news of missions to other parts of the world, to cultural relativism, which saw manifestations of the universal in the local. Jesuits, moreover, were committed to an optimistic theology that perceived linkages with pre - existing spirituality in order to expedite conversion. Yet in the early days of New France, the Jesuits resisted the application of this inclusive theory. While they recognized elements of Algonquian or Iroquoian spirituality - the belief in the afterlife or the practice of sacrifice - as steps on the ladder of spiritual evolution, Jesuits interpreted traditional rituals and rites among both peoples as expressions of ignorance and evidence of an enormous cultural chasm. According to Jesuit commentators, native belief was so ill - formed as to be innocuous, in no way a false religion in opposition to Christianity. 'If there are any superstitions or false religions in some places, they are few. The Canadians think only of how to live and to revenge themselves upon their enemies. They are not attached to the worship or any particular divinity.'(f.58) With few exceptions - one of whom was Brebeuf, whose sensitive account of Huron beliefs furnishes the basis of ethnographic understanding - missionaries were unable to credit native myth and rite with spiritual or transcendental purpose. Instead, they labelled it incoherent and misdirected: autochthonous devotions were simply 'ridiculous.'(f.59) At most, said the more sympathetic Brebeuf, their creed was equivalent to superstition, which 'we hope by the grace of God to change into true religion.'(f.60)

Jesuits recognized the central figure of 'Manitou' in most discussions of Algonquian or Iroquoian views of the spiritual. They did not go on to conflate this figure with the Devil, however, except when simultaneously associating the 'good' Manitou with God. While sometimes identified as a spirit, the 'Manitou' was more commonly interpreted as the locus of spiritual feelings, the product of the superstitious tendencies of ignorant minds. 'When the mind has once strayed from the path of truth, it advances far into error.'(f.61)

Jesuits occasionally proposed a much stronger form of diabolism, which suggested that the Devil availed himself of this error. When Brebeuf described Huron religion in the Relation of 1636, he framed it in terms of natural theology. He suggested that the Devil exploited the contradiction between the natural intelligence of the Huron and their lack of religious enlightenment:

These People are not so foolish as not to seek and to acknowledge something above the senses; and since their lewdness and licentiousness hinder them from finding God, it is very easy for the Devil to thrust himself in and to offer them his services in their pressing necessities, causing them to pay him a homage that is not due him, and having intercourse with certain more subtle minds, who extend his influence among these poor people.(f.62)

Sinful habits presented an opportunity for the Devil, who kept the Huron attached to their various feasts 'as a means of rendering them still more brutal, and less capable of supernatural truths.'(f.63) Brebeuf's investigation turned up evidence of 'something darker and more occult,' suggestive of idolatry.(f.64) Even Brebeuf's Devil, though, was more fox than sheepdog or puppet master: Huron fell under his sway through natural inclination, utterly passively, rather than through conviction of diabolical anti - truth.

Occasionally missionaries used language that suggests analogy with diabolism in Europe. They referred to native ceremonies as Sabbats, or witches' Sabbaths, and spoke of witchcraft (sortilege). But this vocabulary reflected linguistic deficiency, not equivalency: 'Not that the Devil communicates with them as obviously as he does with the Sorcerers and Magicians of Europe; but we have no other name to give them, since they even do some of the acts of genuine sorcerers.'(f.65) These actions included killing one another by 'charms, wishes and imprecations, by the abetment of the Manitou, by poisons which they concoct.' Yet such charms and devices were efficacious because people believed in them, not because of the Devil's agency. 'I hardly ever see any of them die who does not think he has been bewitched,' asserted Le Jeune. According to his observations, though, most of the dying were 'etiques,' suggesting the completely natural, or social, pathologies of malnutrition or consumption.(f.66) Claims of diabolical involvement, in short, reflected untrustworthy rumour and delusion:

The Devil, who is visible to the South Americans, and who so beats and torments them that they would like to get rid of such a guest, does not communicate himself visibly and sensibly to our Savages. I know that there are persons of contrary opinion, who believe in the reports of these Barbarians; but, when I urge them, they all admit that they have seen nothing of that which they speak, but that they have only heard it related by others.(f.67)

Their Manitou might seem responsible for unexplained occurrences - sudden manies, acts of physical violence which left no trace, and appearances of blood without injury - as reported by native informants. Yet missionaries found that it was 'only necessary to make strong objections to their fables, to arrest them and cause them to retract.'(f.68) Jesuits were concerned about the reliability of their unlearned and often religiously suspect witnesses to supernatural activity, and would routinely interrogate them. Since missionaries themselves seldom encountered evidence of diabolical activity, at least in forms they would reveal in the Relations or in their personal correspondence, accounts of the Devil's work are rare indeed.

The question of demonic influence arose most often when missionaries discussed the activities of the shamans, whom we recognize as the Jesuits' primary opponents in the religious sphere. The missionaries labelled them variously as sorciers, Magiciens pretendus, charlatans, and jongleurs. They were always alert to the possibility that the Devil might be at work in their midst. But Jesuits were confident they could contain and even benefit from shamanistic resistance. Confrontation offered the opportunity to demonstrate their rationality and their pedagogy, and to expose the imposture and fraud surrounding the diabolical. Jesuits asserted that magical happenings proclaimed by 'sorcerers' were pure invention. If not fraudulent, they were simply the resonance of centuries of myth and fable, and served not a false God but the all - too - human ends of power. 'For my part,' said Le Jeune, 'I suspect that the sorcerer invents every day some new contrivance to keep his people in a state of agitation, and to make himself popular.'(f.69) Le Jeune's nemesis, a Montagnais named Pigarouich who duelled with the missionary over rival forms of magic, 'was neither Sorcerer nor Magician, but would like very much to be one. All that he does ... is nothing but nonsense to amuse the Savages.'(f.70) Despite the convenient use of the language of superstition and false religion, there was no evidence of the actual involvement of Satan: 'The greater part of these consulters of Manitou are nothing but deceivers & charlatans.'(f.71)

The attack on fraudulent sorcery was prominent in mission accounts in the 1630s and 1640S, and is typical of the harsh approach towards superstition that characterized reformed Catholicism in the seventeenth century.(f.72) Charms, spells, rituals, songs, and divinations practised by sorcerers were duly recorded and denounced as misplaced faith; such descriptions and condemnations constituted in a later age the ethnological lode of the Relations. To the missionaries, the pervasiveness of superstition revealed the social power of the sorcier: 'If one of them should tell the Savages that the Manitou wanted them to lie down naked in the snow, or to burn themselves in a certain place, he would be obeyed. And, after all, this Manitou, or Devil, does not talk to them any more than he does to me.'(f.73) In the Huron country, Brebeuf found that certain sorcerers possessed obscure and finally quite innocuous access to the Devil: 'One is unable to accuse them of falsehoods.' But efficacious or not, these sorcerers did nothing 'without generous presents and good pay.'(f.74) Their pretended diabolism was strictly mercenary.

A rudimentary scientific sense could be part of this dismissal of diabolical shamanism and the attack on the credibility of the sorcerer. Paul Le Jeune confounded one shaman by agitating needles with an unseen magnet. Of course, the danger of appearing too much the sorcerer was always present when Jesuits attempted to play the scientific card: Le Jeune had to protest that his trick 'se faisoit naturellement,' not with diabolical participation.(f.75) Usually it was enough to demonstrate the superior power of Jesuit reason over the incoherent and false message of the sorcerer. In contrast to the delusions of the sorcerer, Jesuits presented the Devil as someone they themselves could master and render impotent if he was caught meddling in human affairs. Exposing the 'shaking tent ceremony' as a fraud in 1637, Le Jeune warned the sorcerer Pigarouich that 'the Devil fears us, and, if it is he [who agitates the tent] I shall speak to him severely, - I shall chide him, and shall force him to confess his impotence against those who would believe in God; and I shall make him confess that he is deceiving you.'(f.76)

In order to gain converts as well as to quash shamanic opposition, Jesuits deployed an 'exoteric' demonology, in what Jean Delumeau argues constitues a 'pastorale de la peur.'(f.77) Although images had always served as the 'books of the poor,' renewed stress on pedagogical technique accompanied post - Reformation confessionalism. Fear - raising pictorial instructional aids were standard fare in the missions to the countryside in France itself, especially where linguistic barriers impeded communication.(f.78) In New France, graphic and theatrical techniques were used to teach the alien concepts of the new religion.(f.79) Knowing that 'these sacred pictures are half the instruction that one is able to give the Savages,' Le Jeune was discerning about their content:

I had desired some portrayals of hell and of lost souls; they sent us some on paper, but that is too confused. The devils are so mingled with the men that nothing can be identified therein, unless it is studied closely. If someone would depict three, four, or five demons tormenting one soul with different kinds of tortures, - one applying to it the torch, another serpents, another pinching it with red - hot tongs, another holding it bound with chains, - it would have a good effect, especially if everything were very distinct, and if rage and sadness appeared plainly in the face of the lost soul. Fear is the forerunner of faith in these barbarous minds.(f.80)

Ideally, such images involved demons and flame - vomiting hells, 'which might strike their eyes and ears.'(f.81) The theme of the diabolical was pursued in theatrical presentations as well: a 1639 pageant to honour the recently born dauphin featured the pursuit of an infidel soul by two demons, which ended predictably enough in Hell, engulfed by flames.(f.82) Yet this demonology related to one's fate after death; the Devil was not depicted in real - world situations. Restricted to his waiting place at the gates of Hell, the Devil left the field open to missionary instruction.

The atmosphere of crisis which attended the early mission, as epidemic disease ravaged the native population in the 1630s, lent circumspection to Jesuit claims about the diabolical, especially in the category of the here and now. Jesuits themselves were accused of sorcery as their 'magic' apparently provided immunity, while Algonquian and Huron communities were decimated. Natives perceived that baptism, as administered to the sick and the dying as a precautionary step, was proving fatal in most cases. Unbelievers argued that the figures depicted in instructional engravings of Hell were victims of the missionary sorcerers.(f.83) In this climate, the rhetoric of diabolism was imprudent: it would further inflame a tense situation.

Occasionally, confrontation with unexplainable phenomena revealed the tension between rationalism and more orthodox credulity. By 1637, for instance, Le Jeune began to change his mind about diabolical activity. Earlier, he had wondered why the Devil seemed to exercise active dominion in South America, while leaving the sauvages of New France inviolate and victims only of the easily refutable practice of the sorcerers. As he became more familiar with the Algonquians, and perhaps frustrated by his failure to learn their arts despite years of study, he began to treat their accounts of the supernatural with circumspection. A Christian informant told Le Jeune of apparitions with powers of augury whom he had encountered in a deep forest. He was warned of impending misfortune for his tribe. If this was not fear that had disturbed the imagination of the young man, thought Le Jeune, it was undoubtedly the Devil.(f.84) The earnest accounts of diabolical agency - be it shaking tents, augury, or efficacious spells - from trusted confidants or from his cohort Pigarouich, further revised this missionary's view of the Devil.(f.85) Le Jeune's colleague Paul Pijart had witnessed a shaman holding a red - hot stone in his mouth without injury; Le Jeune sent the toothmarked stone to his Superior in Paris. 'All these arguments show that it is probable that the Devil sometimes has visible communication with these poor Barbarians' - a reappraisal accompanied by renewed appeals for assistance, both temporal and spiritual, 'to draw them out of the slavery which oppresses them.'(f.86)

Such an attitude surfaced especially in the event of resistance to the missionaries. Jerome Lalemant, who served as superior in the Huron country from 1638 to 1645, suggested that the range of ritual behaviour that persisted in the face of missionary efforts was 'taught by the Demons.' Satan was pleased by the dream - inspired feast of the Huron, Lalemant argued, for 'in it all the internal and external faculties apparently strive to render him a sort of homage and acknowledgement.'(f.87) Lalemant invoked the Devil to explain the persistence of Huron 'superstitions'; he, too, called for additional resources to be marshalled against the Satan's stubborn empire.

While Jesuits only infrequently asserted the Devil's physical presence, they viewed him as the master of illusion, who 'filled their understandings with error and their wills with malice.' The dream was prime terrain for this sort of indirect intervention. Dream - guidance, while regarded by Jesuits and seventeenth - century European learned opinion as madness,(f.88) was a primary spiritual resource for both Algonquian and Iroquoian peoples, a font of information about the afterlife as well as advice in the present. Writing to his brother in 1639, Francois du Peron claimed that

All their actions are dictated to them directly by the Devil, who speaks to them, now in the form of a crow or some similar bird, now in the form of a flame or a ghost, and all this in dreams... They consider the dream as the master of their lives, it is the God of the country; it is this which dictates to them their feasts, their hunting, their fishing, their war, their trade with the French, their remedies, their dances, their games, their songs; to see them in these actions, you would think they were lost souls.(f.89)

Jean de Brebeuf likewise postulated that the Devil manipulated the Huron in the specific idea of a parallel world of the soul, wherein the dead speak to the living: 'Thus it is the devil deceives them in their dreams.'(f.90) This Devil worked obliquely, through suggestion, exploiting his capacity to deceive, rather than directly through instruction. The great unconscious, or the realm of sleep, remained resistant to Christian proselytizing - and indeed persists as the site of survival of North American native spirituality.(f.91)

Confident missionaries who had experience in the mission fields were inclined to total scepticism about diabolical presence. Paul Ragueneau, who in 1645 replaced Jerome Lalemant at the helm of the mission to the Huron country, broadly and comprehensively refuted the claims that the Devil was active among these peoples. In a rationalist vein, he cautioned his fellow missionaries to keep their eye on the real concern: sin, not idolatry:

One must be very careful before condemning a thousand things among their customs, which greatly offend minds brought up and nourished in another world. It is easy to call irreligion what is merely stupidity, and to take for diabolical working something that is nothing more than human; and then, one thinks he is obliged to forbid as impious certain things that are done in all innocence, or, at most, are silly, but not criminal customs. These could be abolished more gently, and I may say more efficaciously, by inducing the Savages themselves gradually to find out their absurdity, and to laugh at them, and to abandon them, - not though motives of conscience, as if they were crimes, but through their own judgement and knowledge, as follies.(f.92)

Ragueneau thereby displaced the Devil, even from the terrain of dreams: 'I do not think that the Devil speaks to them, or has any intercourse with them in that way.'(f.93) Those who claimed that spirits spoke through their dreams exhibited herd mentality and suggestibility. The work of sorcerers was another misguided expenditure of social energies, lacking any connection with the supernatural: 'Having carefully examined all that is said about [witchcraft and sorcery] I have not found any sufficiently rational foundation for the belief that there are any here who carry on that hellish trade.'(f.94) Illness said to be caused by spells proved to be 'tres - naturelles & ordinaires'; whim and prejudice motivated destructive accusations and malicious behaviour. In the corpus of traditional belief, Ragueneau found little menace: error and disorder, yes, and certainly sin, but 'in any case the evil is less than we judged at first, and of far less extent that had appeared.'(f.95) Ragueneau's mid - century views mark the crossing of a watershed in missionary demonology: henceforward, mentions of the Devil, in whatever capacity, steadily drop. In France itself, of course, the Parlement of Paris had moved to suppress prosecution for diabolical witchcraft by the 1660s.(f.96)

The most prominent use of demonology in the early missions was the rhetorical, as ringing statements about the 'Empire of Satan' and the 'Devil's kingdom' may suggest. The mention of the Devil was part of an extended military metaphor in Jesuit discourse.(f.97) In accord with the Spiritual Exercises and a century of confessional sparring, Jesuits presented the Devil as master of opposition when they offered overviews of progress in their mission. Thus the 'stratagems of Satan'(f.98) could account for delay, reverse, or failure in the mission, as in the efforts to settle the Montagnais in the mid - 1630s, or the destruction of the Huron mission in the later 1640S. Resistance could be attributed to 'the purpose of the Devil to spite us, and to thwart the affairs of Christianity.'(f.99) Satan's outrageous counter - assaults drew attention to the issue of support for the mission: 'He employs all the resources of his malice to overthrow this holy enterprise.'(f.100) To highlight the Devil in these ways was to remind the readers of the difficulty of the campaign, and to reinforce resolve on both mission field and home front.

The Jesuit strategy towards the Devil in New France may have reflected an oblique, possibly tactical approach, rather than the Devil's actual dismissal from the mission fields. By restricting mention of the Devil to the chorus or coda of the account of their activity, these missionaries were emphasizing the dignity and the power of the sacred. The troubles of this land were inflicted by a terrible but just God, not the Devil. Epidemic disease, notably, was a mystery comprehended as divine justice, or the 'scourge of God.'(f.101) Jesuits would leave diabolism to their opponents, who needed the scapegoat for the failings of converts or the ineffectiveness of their particular program.(f.102)

However, such tactical concerns were overshadowed by the scepticism Jesuits displayed towards the diabolical. In their understanding of the limited scope of the supernatural and the fraudulent nature of most claims about the Devil, they anticipated Spinoza and Leibniz'(f.103) and prepared the way for the ethnological thrust of later Relations and Lettres edifiantes. While he continued to occupy a place in the minds of these men of faith, the Jesuits' Devil did not obtrude in analysis of the problems of mission. He received, if anything, very weak credit for the ignorance and delusion of these peoples, especially their shamans. In place of the Devil, Jesuits focused on the sins of these peoples, their offence to God, and their correctable ignorance.

The implications of this seemingly 'modern' analysis were not necessarily positive for the stated goal of establishing Christianity. Although it could legitimize conquest, as in New Spain, an active demonology might also serve as a bridge between old religion and new. It provided continuity, a way of identifying religious tendencies within a pagan population. Where diabolical religion, or the Devil's church, could not be identified, or was dismissed as fraudulent and delusional, other expedients had to be adopted. These included the impressive but laborious Jesuit educational programs, and chronically underfunded schemes to 'reduce' Algonquians and Iroquoians to civilization. The disappointment engendered by slow progress could not be projected onto the Devil: instead, the native population bore the brunt.

Did Canada's native peoples benefit in any way from attenuated diabolism? The Devil's low profile in New France spared them anything resembling New Spain's seventeenth - century Campaigns of Extirpation, in which backsliding from Christianity was viewed as recapture by the Devil. But it also meant that the same recognition that missionaries in the previous century had accorded native belief in Mexico and Peru would not be forthcoming to the Algonquians and Iroquoians of Canada. The account of their lives would be framed largely in terms of sin, and their practices scorned for vileness and filth, rather than held up as an form of idolatry to be approached with some respect at least for its potency:

Casting our eyes over the customs and practices of these peoples, they had always appeared to us like stagnant, ill - smelling pools; yet we had hardly seen, in the past, more than the surface. But since we have been obliged, on account of our Christians, to search within, and remove this sewer, it cannot be believed what a stench and what a wretchedness we have found there.(f.104)

The damaging stereotype of a depraved native culture would be perpetuated by subsequent generations of missionary observers. Part of an emerging anthropological view of native life that would be established in the next century,(f.105) the dismissal of the Devil implied the primitiveness of aboriginal culture, and, moreover, made the natives somehow responsible for their shortcomings in the eyes of European educators and administrators. The colonial power would tap these representations of cultural underdevelopment for their political element: if the autochthonous did not even revolve around Devil worship, which was at least a form of organized religion and part of, although the inverse of, the Christian sphere, it must be truly primitive, a tabula rasa on which to inscribe a wholly new set of values. French policy would be characterized by attempts to fill what was perceived to be a cultural and spiritual vacuum. In the absence of conquest, the missing Devil, or the religious void, provided justification for the subjugation of these peoples.

Thus, at the brink of the eighteenth - century Enlightenment, the northern peoples of the New World could be represented as 'Barbarian nations who have no notion of religion, true or false, who lack order, laws, God and religious cult, and whose mind is completely enshrouded in matter and incapable of the most common reasoning of Religion and faith.'(f.106) The practice of building the new religion on the remains of the old would not be followed in New France. Instead, Jesuits taught that once free of ignorance and habitual sin, natives would come over to Christianity unencumbered. The Devil was no more than a bystander to this process.

Footnotes:

(f.1) Francois de Toulouse, Jesus Christ ou le parfait missionnaire (Paris 1662), 44

(f.2) R.G. Thwaites, ed., The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents, 73 vols. (1896 - 1901; New York: Pagent Book Company 1959), 2: 77. Additional material from Monumenta Novae Francia, 6 vols. (Montreal and Rome: Editions Bellarmin 1968 -)

(f.3) For the Jesuit mission to New France, see C. Jaenen, Friend and Foe: Aspects of French - Amerindian Cultural Contact in the Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries (Toronto: University of Toronto Press 1976); M. Trudel, Histoire de la Nouvelle France, 3 vols. (Montreal: Fides 1963 -), vols. 2 - 3, or his shorter work The Beginnings of New France, 1542 - 1663, 2 vols. (Toronto: University of Toronto 1973), vol. 1; L. Campeau, La mission des jesuites chez les Hurons, 1634 - 1650 (Montreal and Rome: Editions Bellarmin 1987). For the Montagnais, an Algonquian people with whom French Jesuits became involved from 1626, and the Huron, Iroquoian peoples of the Great Lakes Region, see E. Tooker, An Ethnography of the Huron Indians, 1615 - 1650 (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press 1964), and J. Helm, ed., Handbook of North American Indians, 8 vols. (Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press 1981), vol. 6.

(f.4) B. Trigger, Children of Aataensic: A History of the Huron People to 1660 (Montreal: McGill - Queen's University Press 1976), 503; K. Anderson, Chain Her by One Foot: The Subjugation of Women in Seventeenth - Century New France (New York: Routledge 1991), 17 - 21, 29; W. Eccles, France in America, 2nd ed. (Markham: Fitzhenry and Whiteside 1990), 45; J.B. Callicott, 'Traditional American Indian and Western European Attitudes toward Nature: An Overview,' in M. Oelschlaeger, ed., Postmodern Environmental Ethics (Albany: State University of New York Press 1995), 193 - 219; F. Parkman, France and England in North America, 2 vols. (New York: Literary Classics of the United States 1983), 1: 487

(f.5) R. Muchembled, ed., Magie et sorcellerie en Europe du Moyen Age a nos jours (Paris: Armand Colin 1994), 102

(f.6) Loyola, Spiritual Exercises, ed. L.J. Puhl (Chicago: Loyola University Press 1951), 60 - 2; medititations, 140 - 2

(f.7) M. - C. Pioffet, 'L'arc et l'epee: Les images de la guerre chez le jesuite Paul Le Jeune,' Rhetorique et conquete missionnaire: Le jesuite Paul Lejeune, ed. R. Ouellet (Sillery: Editions Septentrion 1993), 41 - 52; J. Axtell, The Invasion Within: The Contest of Cultures in Colonial North America (New York: Oxford University Press 1985), 91 - 3

(f.8) Sixteenth - century Jesuit worldview is investigated in A.L. Martin, The Jesuit Mind: The Mentality of an Elite in Early Modern France (Ithaca: Cornell University Press 1988) and J.W. O'Malley, The First Jesuits (Cambridge: Harvard University Press 1993).

(f.9) See E. Pagels, The Origin of Satan (Princeton: Princeton University Press 1995); F. Cervantes, The Devil in the New World: The Impact of Diabolism in New Spain (New Haven: Yale University Press 1994). The best survey of early modern diabolism is found in J.B. Russell, Mephistopheles: The Devil in the Modern World (Ithaca: Cornell University Press 1986), 25 - 126. Russell provides useful background in Lucifer: The Devil in the Middle Ages (Ithaca: Cornell University Press 1984).

(f.10) Pierre Berthiaume has recently investigated the missionary Paul Le Jeune's involvement with the Montagnais 'sorcerer' Carigonan in the winter of 1633 - 4. P. Berthiaume, 'Le missionnaire depossede,' paper presented to 'Decentring the Renaissance: Canada and Europe in Multi - Disciplinary Perspective 1530 - 1700,' Victoria University, Toronto, March 1996

(f.11) French Jesuits made little reference to diabolism when they reported the progress of missions to the Provincial in France or the General in Rome; ascertained in a survey of Jesuit Roman Archives (ARSI), Fondo gallia, vols. 109 - 10, and of correspondence, apart from the printed Relations, which Lucien Campeau compiled in the six volumes of Monumenta Novae Francia.

(f.12) J.C. Baroja, 'Witchcraft and Catholic Theology,' in B. Ankarloo and G. Henningsen, eds., Early Modern European Witchcraft (Oxford: Oxford University Press 1990), 38

(f.13) R. Mandrou, Magistrats et sorciers en France au XVIIe siecle (Paris: Seuil 1980); Russell, Mephistopheles, 83

(f.14) Russell, Lucifer, 274 - 86; Mephistopheles, 24 - 50

(f.15) J. Bossy, 'Moral Arithmetic: Seven Sins into Ten Commandments,' in E. Leites, ed., Conscience and Casuistry in Early Modern Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1988), 229 - 34

(f.16) The term 'idolatry' embraces both worship of an intermediary and a wrong idea of God. See M. Halbertal and A. Margalit, Idolatry, trans. N. Goldblum (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press 1992), for an investigation of ideas of idolatry in the Judeo - Christian tradition; F. Cervantes, The Idea of the Devil and the Problem of the Indian: The Case of Mexico in the Sixteenth Century (London: Institute of Latin American Studies 1991), 11 - 19. See also C.M. Eire, The War against the Idols (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1985), 23 - 55.

(f.17) Cervantes, Devil in the New World

(f.18) Fray Andres de Olmos, Tratado de hechicerias y sortilegios, trans. G. Baudot (1553; Mexico City: Mision Arqueologica y Etnologica Francese en Mexico 1979)

(f.19) D.T. Reff, 'The "Predicament of Culture" and Spanish Missionary Accounts of the Tepehuan and Pueblo Revolts,' Ethnohistory 42 (1995): 63 - 90.

(f.20) Acosta, Historia natural y moral de las Indias, ed. E. O'Gorman (1590; Mexico City: Fondo de Cultura Economica 1962). Acosta's demonology is most prominent in Book v, where American idolatry is described as a function of 'la soberbia y invidia del demonio' (217 - 79). First French edition: Histoire naturelle et morale des indes tant orientales qu'occidentales: Traduite en francais par Robert Regnault (Paris 1598). See also C. Bernand and S. Gruzinski, De l'idolatrie: Une archeologie des sciences religieuses (Paris: Seuil 1987), 146 - 94, and Cervantes, Idea of the Devil, 20 - 5.

(f.21) S. Houdard, Les sciences du diable: Quatre discours sur la sorcellerie (XVe - XVIIe siecle) (Paris: Editions du Cerf 1992); Bernard and Gruzinski, De l'idolatrie, 75 - 88. See also J. Delumeau, La peur en Occident (Paris: Fayard 1975), 335 - 42

(f.22) P. de Lancre, Tableau de l'inconstance des mauvais Anges et Demons ou il est amplement traicte des Sorciers & de la Sorcelerie (Paris 1612), 17

(f.23) N. Forsyth, The Old Enemy: Satan and the Combat Myth (Princeton: Princeton University Press 1987), 3 - 18

(f.24) W.W. Meisner, Ignatius of Loyola: The Psychology of a Saint (New Haven: Yale University Press 1992), 100

(f.25) O'Malley, The First Jesuits, 45

(f.26) Loyola, Spiritual Exercises, Point 141, in Puhl, 61: 'Consider how [the Devil] summons innumerable demons, and scatters them, some to one city and some to another, throughout the whole world, so that no province, no place, no state of life is overlooked.'

(f.27) For medieval demonology, see Russell, Lucifer, or N. Cohn, Europe's Inner Demons (St Alban's: Paladin Press 1975), 65 - 76.

(f.28) J.C. Baroja, The World of the Witches (London: Weidenfield and Nicholson 1964), 41 - 4

(f.29) Aquinas disputed the Platonic conception of evil as inherent, and the idea that the Devil could actually cause sin. The Devil was, instead, chief of the party of evil, composed of people who had chosen to sin. Russell, Lucifer, 193 - 203

(f.30) J.H. Elliott, 'Renaissance Europe and America: A Blunted Impact,' in F. Chiapelli, ed., Images of America in Europe, 2 vols. (Berkeley: University of California Press 1976), 1: 16; J. Bossy, Christianity in the West, 1400 - 1700 (Oxford: Oxford University Press 1985), 138 - 9. For seventeenth - century theology, see M. - C. Varichaud, La Conversion au XVIIe siecle (Paris: Hachette 1975).

(f.31) Marie - Christine Varichaud suggests that the seventeenth - century Devil acted as the Pharoah did to the people of Israel when they left Egypt: he menaces the prospective convert with threats that attend conversion, and attempts to stir up human nature against the proposed action. La Conversion au XVIIe siecle, 7

(f.32) J. Deslyons, Traitez singuliers et nouveaux contre le paganisme du Roy - boit (Paris 1670), 218

(f.33) The focus on sin can be found in a wide range of Jesuit authors, particularly the spiritualist school identified by Henri Bremond in Histoire litteraire du sentiment religieux en France, 11 vols. (1923; Paris: Armand Colin 1967), 5: La conquete mystique: L'Ecole du Pere Lallemant et la tradition mystique dans la Compagnie de Jesus. See P. Champion, La vie du pere Jean Rigoleuc de la Compagnie de Jesus: Avec ses traitez de devotion et ses lettres spirituelles (Paris 1686), 305ff, for a description of the 'state of sin and passion.' E. Bauny, Somme des pechez (Paris 1628), contains a 900 - page catalogue.

(f.34) In February 1599 Marthe Brossier was examined for alleged demonic possession at the Abbey of Ste Genevieve in Paris. Despite the lack of convincing symptoms of supernatural turbulence, and evidence that her condition was in fact epilepsy, a team of five Capuchin priests and five medical doctors found her to be possessed by three devils. She duly underwent a highly publicized exorcism. Henri IV was sceptical, however, and demanded that Brossier be examined by royal physicians, who found that her disorders had nothing of the supernatural about them. In calling for an examination by his doctors, Henri antagonized the ultra - Catholic opposition, who used this evidence of the king's disregard for ecclesiastical practice to mobilize resistance to the Edict of Nantes. See M. Marescot, Discours veritable sur le faict de Marthe Brossier de Romorantin, pretendue demoniaque (Paris 1599).

(f.35) C.E. Williams, The French Oratorians and Absolutism, 1611 - 1641 (New York: Lang 1988), 34 - 5; D.P. Walker, Unclean Spirits: Possession and Exorcism in France and England in the Late Sixteenth and Early Seventeenth Centuries (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press 1981), 33 - 42

(f.36) Cervantes, Devil in the New World, 99 - 102. Compare M. Carmona, Les diables de Loudun (Paris: Fayard 1988), 18 - 45.

(f.37) J. de Guibert, The Jesuits: Their Spiritual Doctrine and Practice, trans. W. Young (Chicago: Institute of Jesuit Sources 1964), 360 - 4

(f.38) Von Spee's Cautio criminalis seu de processibus contra sagas liber: Authore incerto theologo orthodoxo (Vienna 1631) was translated into French by F. Bouvet, under the title Advis aux criminalistes sur les abus qui se glissent dans les proces de sorcellerie ... Livre tres necessaire en ce temps icy a tous juges, conseillers, confesseurs (tant des juges que des criminels), inquisiteurs, predicateurs, advocats, et meme aux medecins par le P.N.S.J, theologien romain (Lyons 1660).

(f.39) Compare Mandrou, Magistrats et sorciers, 195 - 363.

(f.40) P. Burke, The Historical Anthropology of Early Modern Italy (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1987), 48 - 62

(f.41) Francois de Toulouse, Le missionaire apostolique ou Sermons utiles a ceux qui s'employent aux missions, pour retirer les hommes du peche & les porter a la penitence, 12 vols. (Paris 1666 - 7), 1: 47 - 87

(f.42) D.P. Walker, The Decline of Hell (Chicago: University of Chicago Press 1964), 4 - 8

(f.43) R. Briggs, Communities of Belief: Social and Cultural Tensions in Early Modern France (Oxford: Oxford University Press 1989), 47 - 53

(f.44) L. Daston, 'Wunder, Naturgesetze und die wissenschaftliche Revolution des 17 Jahrhunderts,' Jahrbuch der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Gottingen (1991): 99 - 122

(f.45) For 'renaissance naturalism,' see W.L. Hine, 'Marin Mersenne: Renaissance Naturalism and Renaissance Magic,' in B. Vickers, ed., Occult and Scientific Mentalities in the Renaissance (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1984), 165 - 76.

(f.46) Francois de Dainville, La geographie des humanistes (Paris: Editions Beauchesne 1940)

(f.47) Acosta, Historia, Libro 1, cap. 16 - 25

(f.48) S.J. Harris, 'Transposing the Merton Thesis: Apostolic Spirituality and the Establishment of the Jesuit Scientific Tradition,' Science in Context 3 (1989): 29 - 65

(f.49) Jesuit Relations, 6: 145

(f.50) As we can see in the trickle of immigration to official destinations, the concentration of exoticism in the Near East and the Orient, and the minor role of New France in emerging 'public' discourse. For the Catholic world's lack of interest in Canada, see L. Codignola, 'The Holy See and the Conversion of the Indians in French and British North America, 1486 - 1760,' in K.O. Kupperman, ed., America in European Consciousness (Durham: University of North Carolina Press 1995), 195 - 242. Jesuits themselves did not make Canada their first choice very often; rather, they were lured by the missions to China and the Indies. See D. Des landres, 'Missions et alterite: Les missionaires francais et la definition de l'"autre" au XVIIe siecle,' Proceedings of the Eighteenth Meeting of the French Colonial Historical Society (1993) 5 - 10.

(f.51) The 'spiritual leader' of the Canada missionary movement, Louis Lallement, believed that the Canadian mission field 'est plus feconde en travauxs & en croix; elle est moins eclatante, & contribue plus que les autres a la sanctification de ces missionnaires.' Lallement, La doctrine spirituelle de Louis Lallement, ed. P. Champion (1685; Avignon 1781), 10

(f.52) See N. Duran, Relations des insignes progrez de la Religion Chrestienne faits au Paraguay ... trans. J. Machaud (Paris 1638).

(f.53) Bernardino de Sahagun, A History of Ancient Mexico, trans. F.R. Bandelier (1547 - 77; Detroit: Blaine Ethridge Publishers 1971), 21 - 4

(f.54) Jesuit Relations, 5: 231

(f.55) Briggs, Communities of Belief, 294 - 302

(f.56) Jesuit Relations, 5: 25

(f.57) Ibid., 8: 117

(f.58) Ibid., 5: 35

(f.59) Ibid., 6: 227

(f.60) Spiritual Exercises, 8: 121

(f.61) Jesuit Relations, 6: 205 - 7

(f.62) Ibid., 10: 193

(f.63) Ibid., 177

(f.64) Ibid., 209

(f.65) Ibid., 12: 7

(f.66) Ibid.

(f.67) Ibid., 6: 201

(f.68) Ibid., 5: 159

(f.69) Ibid., 6: 193

(f.70) Ibid., 199 - 201

(f.71) Ibid., 5: 159

(f.72) Compare J. - B. Thiers, Traite des superstitions, (1689; Paris: Editions le sycomore 1984). Thiers, less a 'homme de terrain' than the Jesuit missionaries, went much further in linking superstitions with diabolism: 'c'est avec grande raison que Dieu a fait defense aux hommes dans le Decalogue de se servir d'aucune Superstition, puisqu'ils ne peuvent en user qu'auparavant ils n'ayent fait un pacte expres, ou du moins tacite, avec le Demon. Car qui dit Superstition, dit de necessite pacte avec le Demon' (56). R.J.W. Evans explains such hostility towards illicit superstition and magic as a corollary to reformed Catholicism's reliance on 'white magic.' The Making of the Habsburg Monarchy, 1550 - 1700 (Oxford: Oxford University Press 1979), 344 - 5

(f.73) Jesuit Relations, 5: 158

(f.74) Ibid., 8: 123

(f.75) Ibid., 11: 260

(f.76) Ibid., 257

(f.77) J. Delumeau, Le peche et la peur (Paris: Fayard 1983), 369 - 530

(f.78) Instructional aids ('Daouzek Taolen') were developed for the Breton missions c. 1650. See M. Le Nobletz and J. Maunoir, Daouzek Taolen Ann Tad Maner (Tours 1887), a collection of the engravings used in the field. Je remercie le Pere Roger Tandonnet, SJ, de la Bibliotheque des Fontaines, Chantilly, pour cette reference.

(f.79) F. - M. Gagnon, La conversion par l'image (Montreal: Editions Bellarmin 1975). For parallels between the missions to New France and the 'missions a l'interieur,' see A. Croix, 'Missions, Hurons et Bas - Bretons au XVIIe siecle,' Annales de Bretagne et des Pays de l'ouest 95 (1988): 487 - 98.

(f.80) Jesuit Relations, 11: 89

(f.81) Ibid., 18: 87

(f.82) Ibid.

(f.83) See ibid., 14: 53, 105, 253.

(f.84) Ibid., 12: 16

(f.85) Ibid., 17 - 23

(f.86) Ibid., 23

(f.87) Lalemant's lengthy description, and condemnation, of Huron ritual practice is found in The Jesuit Relations, 17: 145 - 215. Lalemant, of the Jesuit superieurs perhaps the least of a 'homme de terrain,' resembles the demonologue J. - B. Thiers, whose 1689 Traicte des superstitions deciphered the range of folk traditions as an absolute expression of fealty to the Devil.

(f.88) Missionaries referred to the 'folie' of believing one's dreams (Jesuit Relations, 5: 152); they may have alluded to what M. Foucault describes as the 'unreason of the imagination.' Madness and Civilization, trans. R. Howard (New York: Vintage 1965).

(f.89) Jesuit Relations, 15: 179

(f.90) Ibid., 10: 146 - 8

(f.91) Le Jeune encountered subtle criticism of Christian imperialism when he castigated a neophyte for his attachment to dream augury: 'He replied to me that all nations had something especially their own; that, if our dreams were not true, theirs were.' Jesuit Relations, 5: 159 - 61

(f.92) Ibid., 33: 145

(f.93) Ibid., 197

(f.94) Ibid., 217

(f.95) Ibid., 209

(f.96) A. Soman, 'La decriminalisation de la sorcellerie en France,' Histoire, economie et societe 4 (1985): 179 - 203

(f.97) R. Ferland, Les Relations des jesuites: Un art de la persuasion (Quebec: Editions de la Huit 1992), 103 - 8

(f.98) Jesuit Relations, 10: 77

(f.99) Ibid., 17: 167

(f.100) Ibid., 16: 187

(f.101) Ibid, 39: 141

(f.102) For example, the Recollets (Franciscans) in the Gaspesie in the 1670s stressed diabolism in Indian life. Chrestien LeClerq, Nouvelle relation de la Gaspesie (Paris 1691), 332 - 5. Tension in missionary relations in northern Mexico in the late seventeenth century suggests that Franciscans revived demon - bashing as a way of building their credit; their Jesuit and Carmelite rivals were much more circumspect, accusing the Franciscans of recklessness, if not heresy. See F. Cervantes, 'The Devils of Queretaro,' Past and Present 130 (1992) 51 - 69.

(f.103) S. MacCormack, 'Demons, Imaginations, and the Incas,' Representations 33 (1991): 121 - 46, discusses how 'demons were losing their explanatory usefulness,' exemplified in Spinoza's claim that 'demons were nonexistent because no clear and unequivocal ideas could be formed about them' (141 - 2).

(f.104) Jesuit Relations, 27: 145

(f.105) See M. Duchet, Anthropologie et histoire au siecle des Lumieres (Paris: Flammarion 1977).

(f.106) L. Hennepin, Nouveau voyage d'un Pais plus grande que l'Europe (Utrecht 1698), 383 Earlier versions of this paper were presented in 1994 to the Guelph - Waterloo - Wilfrid Laurier History Conference and to the Erench Colonial Historical society. I would like to thank Michael Ruse for his comments on an early draft, and the anonymous readers for their suggestions.

Word count: 10241

Copyright University of Toronto Press Mar 1997

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

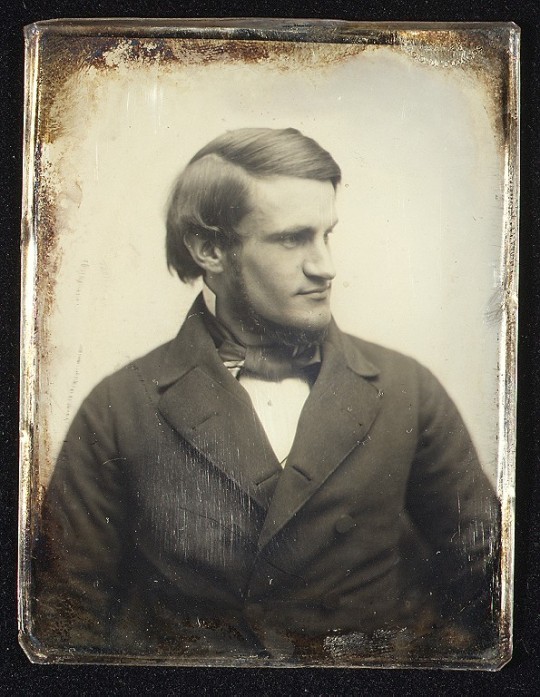

Alredered Remembers American historian Francis Parkman, on his birthday.

"Versailles was a gulf into which the labor of France poured its earnings; and it was never full."

-Francis Parkman

0 notes

Text

What Christians Can Learn from the Devotional Poetry of Hindu South India (webinar)

What Christians Can Learn from the Devotional Poetry of Hindu South India

Free online seminar:

Speaker: Professor Francis Clooney, SJ, FBA, Parkman Professor of Divinity and Comparative Theology, Harvard Divinity School, USA.

Date: 5 December, 2022

Register at https://www.oxfordinterfaithforum.org/programs/thematic-international-interfaith-reading-groups/philosophy-in-interfaith-contexts/what-christians-can-learn-from-the-devotional-poetry-of-hindu-south-india/

As someone connected to the 'Yeshu Bhakti' movement of India and the Diaspora, I'm interested in this topic.

+++

Father Francis Clooney, S.J., is an American Jesuit and the Parkman Professor of Divinity and Professor of Comparative Theology at the Harvard Divinity School. He is also the director of the Center for the Study of World Religions at Harvard and a fellow of the British Academy. His academic work focuses on theological commentarial writings in the Sanskrit and Tamil traditions of Hindu India, as well as the developing field of comparative theology, and he is the author of numerous scholarly books and articles.

He was the first president of the International Society for Hindu-Christian Studies.

He has written 10 major books and many articles. Learn more at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Xavier_Clooney

0 notes

Text

PDF The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York PDF -- Robert A. Caro

Read PDF The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York Ebook Online PDF Download and Download PDF The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York Ebook Online PDF Download.

The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York

By : Robert A. Caro

DOWNLOAD Read Online

DESCRIPTION : One of the most acclaimed books of our time, winner of both the Pulitzer and the Francis Parkman prizes, The Power Broker tells the hidden story behind the shaping (and mis-shaping) of twentieth-century New York (city and state) and makes public what few have known: that Robert Moses was, for almost half a century, the single most powerful man of our time in New York, the shaper not only of the city's politics but of its physical structure and the problems of urban decline that plague us today.In revealing how Moses did it--how he developed his public authorities into a political machine that was virtually a fourth branch of government, one that could bring to their knees Governors and Mayors (from La Guardia to Lindsay) by mobilizing banks, contractors, labor unions, insurance firms, even the press and the Church, into an irresistible economic force--Robert Caro reveals how power works in all the cities of the United States. Moses built an empire and lived like an emperor. He

0 notes

Text

Download PDF The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York PDF -- Robert A. Caro

Read PDF The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York Ebook Online PDF Download and Download PDF The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York Ebook Online PDF Download.

The Power Broker: Robert Moses and the Fall of New York

By : Robert A. Caro

DOWNLOAD Read Online

DESCRIPTION : One of the most acclaimed books of our time, winner of both the Pulitzer and the Francis Parkman prizes, The Power Broker tells the hidden story behind the shaping (and mis-shaping) of twentieth-century New York (city and state) and makes public what few have known: that Robert Moses was, for almost half a century, the single most powerful man of our time in New York, the shaper not only of the city's politics but of its physical structure and the problems of urban decline that plague us today.In revealing how Moses did it--how he developed his public authorities into a political machine that was virtually a fourth branch of government, one that could bring to their knees Governors and Mayors (from La Guardia to Lindsay) by mobilizing banks, contractors, labor unions, insurance firms, even the press and the Church, into an irresistible economic force--Robert Caro reveals how power works in all the cities of the United States. Moses built an empire and lived like an emperor. He

0 notes

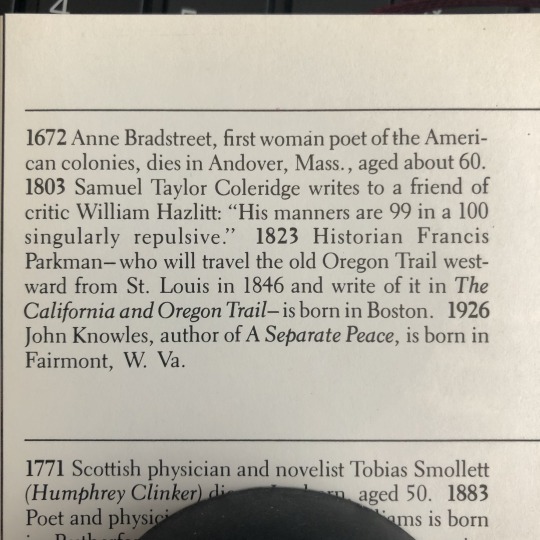

Photo

Literary history that happened on 16 September

#september 16#literary history#literary#history#literature#on this date#john knowles#samuel taylor coleridge's daughter#anne bradstreet#francis parkman

137 notes

·

View notes

Text

It’s possibly not as exciting as it seems hahaha

It’s from Francis Parkman’s The Old Regime in Canada, part 4 of his collection France and England in North America, first published in 1874. In a chapter about the Acadian Civil War, Parkman describes how Charles de la Tour had gone to Boston for reinforcements, and so he’s describing the Boston Common where the militia met:

The stated training-day of the Boston militia fell in the next week, and La Tour asked leave to exercise his soldiers with the rest. This was granted; and, escorted by the Boston trained band, about forty of them marched to the muster-field, which was probably the Common, - a large tract of pastureland in which was a marshy pool, the former home of a colony of frogs, perhaps not quite exterminated by the sticks and stones of Puritan boys. This pool, cleaned, paved, and curbed with granite, preserves to this day the memory of its ancient inhabitants, and is still the Frog Pond, though bereft of frogs. (26)

I thought this was just hilarious for some reason.

I think because Francis Parkman is just so Classical Historian, and it’s just such a funny but still uptight line. “...though bereft of frogs.” If you try to hear it in like Old Man Historian voice it’s just so funny. :D

If anyone has the desire to read this book, there are a bunch of online editions, including on the Internet Archive.

1 note

·

View note

Photo

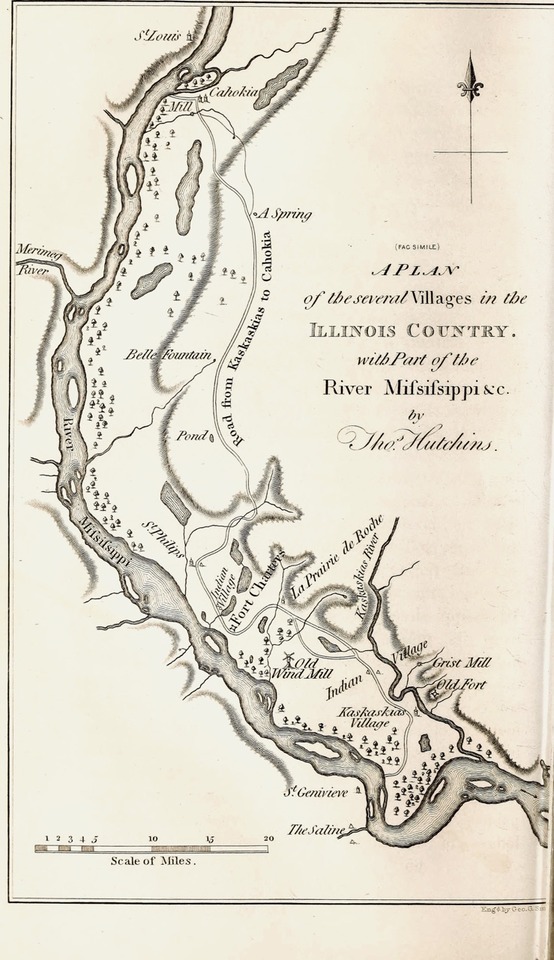

Image from page 553 of “History of the Conspiracy of Pontiac” (1851); book by Francis Parkman

#vintage books#francis parkman#vintage maps#american history#mississippi river#north american history#illinois

24 notes

·

View notes

Quote

Soft-hearted philanthropists may sigh long for their peaceful millennium; for from minnows up to men, life is an incessant battle.

Francis Parkman

#philanthropists#humanitarianism#world peace#peace#quotes#battle#struggle#life struggle#human nature#depressing#francis parkman#gritty

0 notes

Text

Close-up view of an arch detail in the Parkman Branch Library, Detroit Public Library. Typed on back; "Detroit Public Library. Francis Parkman Branch. Detail of arch."

Courtesy of the Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library

#parkman branch library#detroit#parkman#detroit public library#arch#architecture#library#libraries#library buildings#art

49 notes

·

View notes

Text

While French-language scholars of the Jesuit mission in Canada were at

the forefront, there were several English-speaking historians, who form

the third category. Among these historians are William Smith (1769–

1847), John Mercier McMullen (1820–1907), Francis Parkman (1823–

93) and Thomas J. Campbell (1848–1925). Smith and McMullen should

be noted for their ignorance of the Jesuit mission. In writing about the

same seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Canada that French-language

contemporaries dealt with, Smith totally omitted the Jesuit missionary

activity from his account. Born in New York and educated in England,

Smith was an Anglo-Saxon bureaucrat in Lower Canada, home of the

majority of French Canadians. For Smith to keep the peace and to maintain his position as a career civil servant, it was no doubt wise to omit any

negative comments on the Jesuits in Lower Canada, lest he should incur

the wrath of the overwhelming francophone majority.39

Similar omissions can be found in the general history of John M.

McMullen, an Irish Canadian in Canada West, now part of Ontario. As

in the monograph by Smith, the seventeenth-century under the Jesuit

leadership was outside McMullen’s academic concerns. Thus, he merely

touched on the mission and native peoples in one short passage. In his

Anglo-centric version of Canadian history, Canada had progressed by

turning its back on fierce native populations to welcome Anglo-Saxon

immigrants, who became his main focus.40

On the other hand, although he was an Anglophone Protestant, the

American historian Francis Parkman treated the Jesuit mission as the

central subject of study in his classic The Jesuits in North America in

the Seventeenth Century.

41 There are two significant points in Parkman’s

39 William Smith, History of Canada; from Its First Discovery till the Year 1791 (2 vols.

Québec: John Neilson, 1815). The first volume has the title History of Canada; from Its

First Discovery till the Peace of 1763, but it is altered as above in the second volume.

His work did not appear in print immediately and became available as late as 1826. For

Smith’s socially complicated situation, see J. M. Bumsted, ‘William Smith Jr. and The

History of Canada’, in Lawrence H. Leder (ed.), Loyalist Historians, Vol. I of Colonial

Legacy (New York: Harper & Row, 1971), 182–201; and Bumsted, ‘William Smith’,

Vol. VII of Dictionary of Canadian Biography (1988), 816–19. 40 John M’Mullen [McMullen], The History of Canada from Its First Discovery to the

Present (Brockville, C. W.: J. M’Mullen [McMullen], 1855), pp. xiv & 31. The book was