#george more o'ferrall

Text

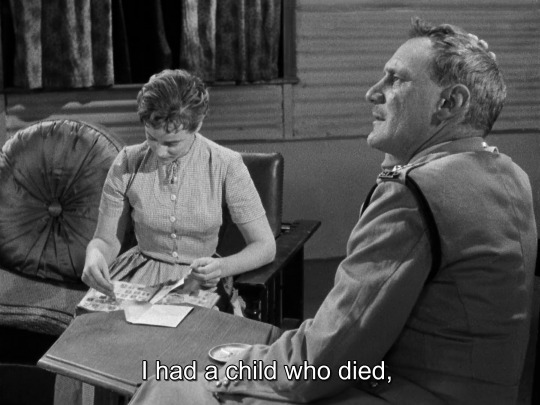

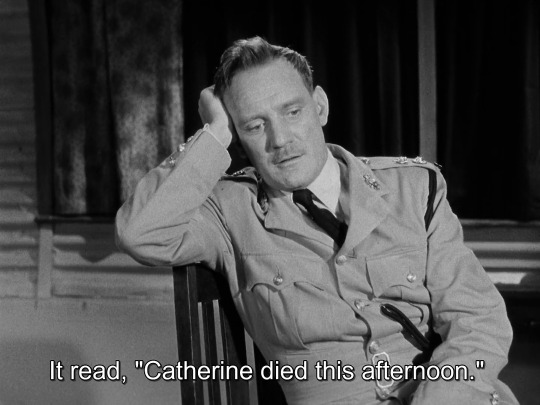

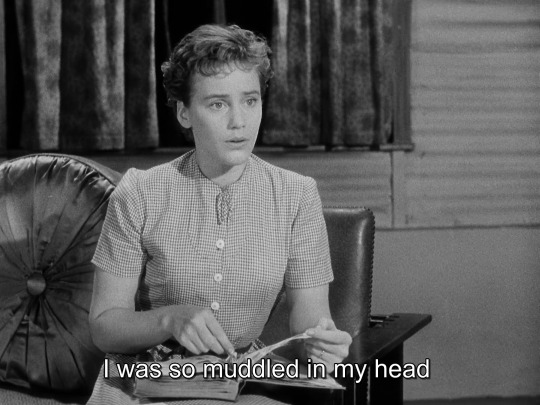

The Heart of the Matter (George More O'Ferrall, 1953).

#the heart of the matter#George More O'Ferrall#trevor howard#maria schell#Jack Hildyard#Sidney Stone#Joseph Bato#Julia Squire

218 notes

·

View notes

Photo

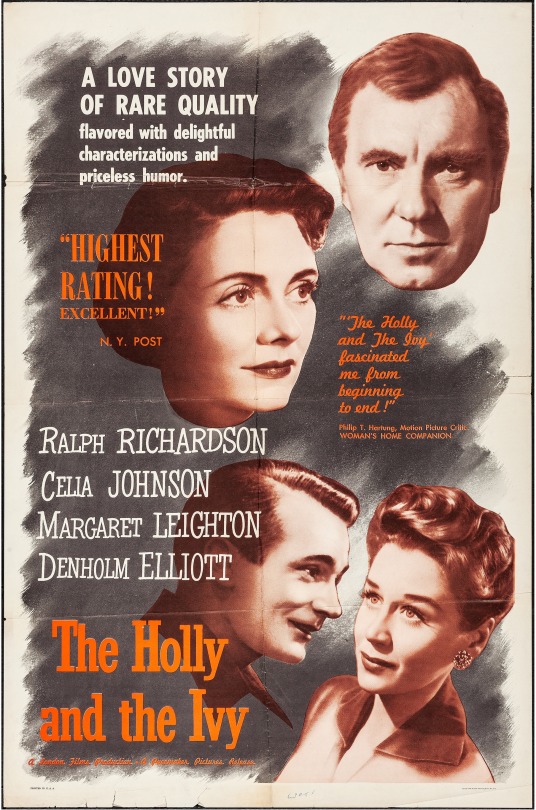

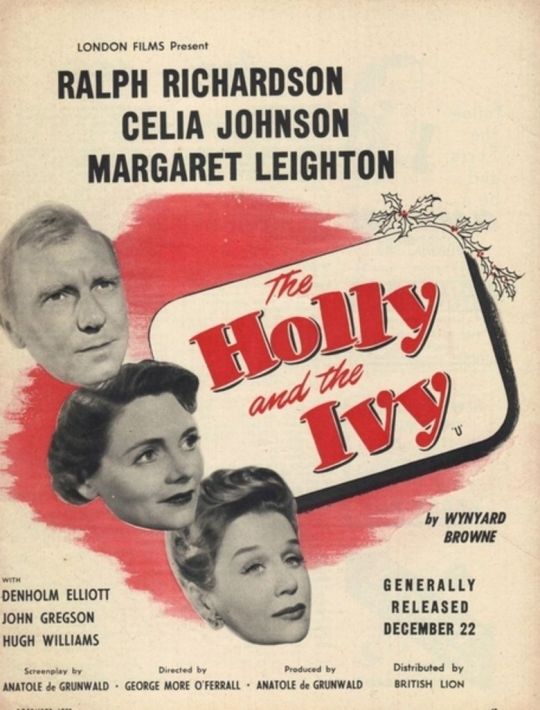

Margaret Halstan, Ralph Richardson & Celia Johnson in “The Holly and the Ivy”, 1952. Dir. George More O'Ferrall.

#The Holly and the Ivy#Christmas#Margaret Halstan#Ralph Richardson#Celia Johnson#Nosso Natal em Família#George More O'Ferrall#1950s#1952#Unforgettable A&A&D#Unforgettable Movies#Nostalgiepourmoi

30 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Holly and the Ivy (1952) George More O’Ferrall

December 17th 2022

#the holly and the ivy#1952#george more o'ferrall#ralph richardson#celia johnson#margaret leighton#john gregson#margaret halstan#maureen delaney#denholm elliott#hugh williams#william hartnell#wynyard browne's the holly and the ivy

10 notes

·

View notes

Text

#The Holly and the Ivy#Ralph Richardson#Celia Johnson#Margaret Leighton#Denholm Elliott#John Gregson#Hugh Williams#George More O'Ferrall#1952

0 notes

Photo

The Holly and the Ivy(1952)

#film#theatre#the holly and the ivy#1952#celia johnson#margaret leighton#george more o'ferrall#wynyard browne#50s#vintage#...

1 note

·

View note

Photo

Three Cases of Murder

directed by David Eady, George More O’Ferrall, Wendy Toye, and Orson Welles, 1955

#Three Cases of Murder#The Picture#You Killed Elizabeth#Lord Montdrago#David Eady#George More O'Ferrall#Wendy Toye#Orson Welles#movie mosaics#Hugh Pryse#Emrys Jones#Eddie Byrne#Alan Badel#Helen Cherry#John Gregson#Elizabeth Sellars

9 notes

·

View notes

Audio

Submitted for your approval are THREE CASES OF MURDER (1955, Toye, Eady, More O'Ferrall, Welles), an anthology film from Britain featuring Alan Badel and Orson Welles. Some segments are better than others, but all are restrained in that British sort of way... are they thrilling enough to be horror?

Context setting 00:00; First segment synopsis 32:04 and discussion 37:45; Second segment synopsis 45:33 and discussion 52:08; Third segment synopsis 1:03:13 and discussion 1:07:42; Ranking 1:14:47

#podcast#horror#david eady#george more o'ferrall#wendy toye#orson welles#sidney carroll#ian dairymple#alexander paal#alan badel#john gregson#elizabeth sellars#emrys jones#hugh pryse#andre morell#wessex film productions#london films#british horror#horror anthology#w somerset maugham#in the picture#you killed elizabeth#lord mountdrago#three cases of murder#film review

6 notes

·

View notes

Text

The Holly And The Ivy (1952)

"Why do you think I became a parson in the first place? Because I saw what life was like, not because I didn't!"

#The holly and the ivy#british cinema#Christmas film#1952#ralph richardson#celia johnson#margaret leighton#denholm elliott#John Gregson#Hugh Williams#Margaret Halstan#Maureen Delaney#william hartnell#Robert flemyng#Roland culver#john barry#Dandy nichols#George More O'Ferrall#Anatole de Grunwald#Wynyard Browne#Play adaptation#Is it too early for Xmas films? Idk. Idc. But actually this isn't a particularly festive Christmas film at all. It's a true melodrama#Full of secrets and lies and histrionics. But it is set at Xmas and in true Christmas fashion everything is sorted and everyone#Relatively happy by the end. It gets a bit heavy in the journey to that happyish ending tho. Stagey and very much a product of its#Time in its attitude to the younger generation and the horror of their waning faith in Christianity but charming enough to sell it#And with a top rate cast for what is essentially a b movie (or a very minor A anyway). Gregson and Elliott are baby faced and fresh with#Long careers ahead of them. Richardson was well established already of course. Hugh Williams is sadly underused in a part#That has promise and could have grown into something much more interesting. And poor lovely celia Johnson is much put upon and#Underappreciated by her family (until the finale of course when she gets her happy ever after. Merry Xmas!!)#films i done watched

11 notes

·

View notes

Photo

The Holly and the Ivy (1952)

While learning about the major religions in middle school, I had acquaintances and friends who were and still are devout Christians. This is a common occurrence in the United States, where evangelical devotion to a Christian God comprises the demographic majority. The way these friends and acquaintances protested my skepticism about Biblical stories and concepts hardened their rhetoric, resulting in a coldness and distance that – in some instances, would never be repaired. Many years removed from those days, I now find myself fascinated by films that remark upon the role of faith in a Christian context without dogmatism. These films can appear in the context of a sprawling Biblical epic like Nicholas Ray’s King of Kings (1961), or maybe in a more intimate drama like One Foot in Heaven (1941) and certainly the subject of this piece, George More O’Ferrall’s The Holly and the Ivy.

The Holly and the Ivy, adapted from the Wynyard Browne play of the same name and released in the United States in 1954, is a yuletide drama set in the English countryside. This film is indicative of what mainstream British cinema looked like in the years following World War II; these homespun post-War dramas that foretold the future social realist films that would start appearing in the late ‘50s. Modestly budgeted and shot in two weeks, The Holly and the Ivy does feel limited by its stageplay origins, but the collective acting and excellent adaptation of the source material override these constraints. The film touches upon Christianity confidently, bereft of the self-righteousness that pervades too many Christian “faith-based” films of the early twenty-first century.

Martin Gregory (Ralph Richardson) is the local parson of the fictional rural town of Wyndenham in Norfolk. He is expecting his younger daughter Margaret (Margaret Leighton), son Michael (Denholm Elliott), and sisters/sisters-in-law Aunt Bridget (Maureen Delany) and Aunt Lydia (Margaret Halstan) to spend Christmas with him at his Wyndenham home. Elder daughter Jenny (Celia Johnson) still lives with Martin, tending to the family home and her father, with her mind wondering about the possibility of life far from Wyndenham. Her loved one, David (John Gregson), is leaving for South America for engineering work, but her dedication to her father makes the possibility of marrying and leaving with David impossible. Because of her father’s commitment to the ministry, Jenny feels she cannot address these concerns with him. So too feel Margaret and Michael, given her struggles with alcoholism and personal secrets and his indignation towards Martin’s concentration on his work at the expense of his family.

In the film’s opening half, we see these withheld tensions seethe in conversations between the Gregory siblings or with their aunts. Years of pent-up disappointment, resentment, and silence threaten to explode in an unseasonal way. The freezing weather, almost entirely confining the Gregory family indoors from the moment they return home, brings about the winter melancholy in some (namely Margaret) more than others. Though The Holly and the Ivy concludes too abruptly with its happy ending (it could use with an additional ten or twenty minutes), this is not the tale of a family enjoying the picturesque postcard Christmas of a Hallmark Channel production. Before some longtime readers start requesting I start reviewing Hallmark Channel Christmas movies (according to the rules of this blog, all films debuting on American television are ineligible), The Holly and the Ivy’s familial drama assumes religious elements and, in one case, trauma that for some viewers may strongly identify with – whether they see themselves or someone close to them. Those are heady concepts not associated with low-budget television movies.

It is apparent that Martin, from the moment he is given an extended intimate scene that does including extending pleasantries, is a parson questioning whether he has impacted the lives of his neighbors. Whether viewing the townspeople from his view at the podium or at home, Martin expresses doubt his actions have been meaningful beyond baptisms, weddings, funerals. Overhearing that Margaret and Michael are off to see a film late on Christmas Eve, Martin observes that, “[the church is] the center of the place architecturally. It should be the center of the place spiritually, too. But it’s not. No. That little tinpot shack of a cinema they’re going to tonight has more influence on the lives of people here than the church.” Martin assumes a facade when Aunt Lydia suggests that he should consider hanging up his collar. Dropping his insecurities, Martin disagrees – Wyndenham needs him, even if his Sunday services are attended dutifully and not enthusiastically.

Martin is in for an unpleasant surprise as the sun rises on Christmas Day, when he learns his children cannot trust their most vulnerable intimations to him, in fear of judgment and the wrath of a servant of God. That which he distresses the most is realized. The walls of his church and his household were not built to keep problems out; his parsonage intending to serve those who suffer, be they righteous or sinful. How Martin works through this familial crisis on Christmas morning is a challenge that he meets with his decades of bringing allegories and parables to those in his flock that might listen. Often, films will depict a religious leader as an unchallenged, immovable figure – set in their ways, unwavering in their faith, unable to see where they are wrong. These cinematic religious leaders – fictitious or otherwise – can be found in hagiographic biopics, farcical comedies, ripped-from-the-headlines dramas based on actual events, original and adapted fictitious dramas. Ralph Richardson, as Martin, is in full command of his part – allowing the audience to see Martin’s anguish as he acknowledges how he has failed his children. Moved by what they say, he knows he must commit to radical personal changes.

Just as importantly, Martin can prevent himself and his children from falling into Christmastide despair through his faith and his experiences with his congregation. The Christian values he preaches and practices has not been a hindrance to loving his children; they have helped him identify immediately where his children are coming from when they address their suffering and inability to trust him with certain topics for the first time. Even if Martin has never encountered a dilemma akin to what his family is going through, he at least has the capacity to ascertain where he has behaved and believed incorrectly. The central conflict in The Holly and the Ivy is distinctly Christian, but is accessible to those of other and no faiths. This is a reflection of how sensitive Wynyard Browne’s original play and Anatole de Grunwald’s adapted screenplay approach these characters: adults, reminiscing about their carefree childhood, only seeing each other around Christmas, noting how the travails and divergences of adulthood have frayed their ties with each other – and their father.

Perhaps the situation in The Holly and the Ivy is not unlike what you experience around the holiday season – the film is extremely British in its occasional use of British and Irish slang (which the captions on the print of the film I saw labeled as “[inaudible]”). Nor will all viewers identify with the religious devotion exemplified in Martin (his children have varying relationships with the church they were raised with) or the family structure depicted within. Where The Holly and the Ivy succeeds in transcending its geographic and religious specificity are the parent-adult child bonds that grow beyond youth – capturing adult suffering and the love of an elder parent. It is where forgiveness and healing begin.

Shot in fourteen days in sequence after three weeks of rehearsal, production on The Holly and the Ivy followed a sequential shooting schedule. This allowed the actors to better inhabit their respective characters’ emotions as the film continues. The decision is a resounding success – the film is better-known in its native Britain than it is in North America (where it seemed to have been respected by critics, but little else). And though The Holly and the Ivy might be too emotionally strenuous for some around years’ end, it is a film deserving to be considered a holiday classic.

My rating: 8/10

^ Based on my personal imdb rating. My interpretation of that ratings system can be found here.

#The Holly and the Ivy#George More O'Ferrall#Ralph Richardson#Celia Johnson#Margaret Leighton#Denholm Elliott#Hugh Williams#John Gregson#Margaret Halstan#Maureen Delany#Wynyard Browne#Anatole de Grunwald#Malcolm Arnold#TCM#My Movie Odyssey

0 notes

Text

THE HOLLY AND THE IVY (Dir: George More O'Ferrall, 1952).

It has now been a few weeks since I watched this movie and I appear to have misplaced my notes. So, please forgive me for a review which is even lighter on insight and heavier on vague observances than usual!

Based on a play by Wynyard Browne, The Holly and the Ivy relates the story of a Christmas family reunion of the Gregory family, the patriarch of which is a seemingly stuck in his ways, traditionalist village pastor (Ralph Richardson); resented by his grown up family, who feel he has neglected them in favour of his parishioners. Tensions rise and family secrets are revealed before the expected reconciliation on Christmas morning.

A Christmas movie that previously flew under the radar, the reputation of The Holly and the Ivy seems to have grown in recent years. With its scintillating scandals and family feuds it is little more than the stuff of soap opera, but it is high class soap opera at that. Director George More O'Ferrall handles the potentially melodramatic subject in a low-key, restrained fashion, eliciting natural, believable performances from his cast.

At age 50, Ralph Richardson is a little too young to fully convince as the aged Reverend Gregory. It is an otherwise great performance, but the role would undoubtedly have benefited from the casting of an actor of more maturity. As his daughters, Celia Johnson and Margaret Leighton are the real standouts. Both convey their individual personal trauma with empathy and sensitivity. In an early appearance for the actor, the great Denholm Elliott also impresses as the alcohol dependent son.

The Holly and the Ivy offers little that hasn't been seen in countless other family dramas; its situations the now familiar tropes of formulaic 'Movie of the Week' features. Yet it is told with a sensitivity generally missing from such made for TV movies. It boasts a superior cast and strong direction from O'Ferrall. It also benefits from a warm nostalgia that tempers the sensationalist aspects of the story. While perhaps not quite a top drawer festive feature, it is a minor Christmas classic nonetheless.

100+ movie reviews now available on my blog JINGLE BONES MOVIE TIME! Link below.

#the holly and the ivy#george more o’ferrall#wynyard browne#ralph richardson#celia johnson#margaret leighton#denholm elliott#classic movies#british film#british cinema#christmas#christmas movies#movies#movie reviews#every movie i watch 2020

1 note

·

View note

Photo

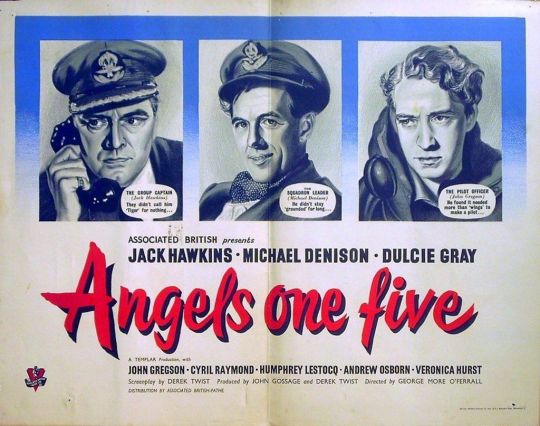

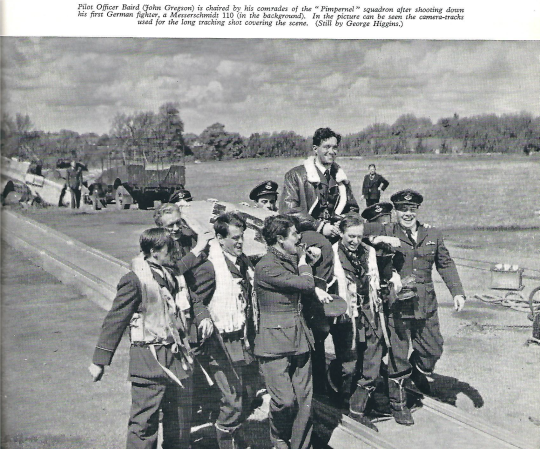

Angels One Five (1952) George More O’Ferrall

August 26th 2022

#angels one five#1952#george more o'ferrall#jack hawkins#john gregson#michael denison#cyril raymond#dulcie gray#humphrey lestocq#veronica hurst#norman pierce#hawks in the sun

0 notes

Photo

25 Old Hollywood Christmas Films (in no particular order) [14/25]

The Holly and the Ivy (1952)

#the holly and the ivy#my edit#25 OH xmas films#george more o'ferrall#celia johnson#denholm elliott#john gregson#i'll get queue my pretty

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

Alice in Wonderland (1946)

Thanks to my friend someperson42 on youtube, we have a little more information on the 1946. As it says "second performance" in the source, this was probably broadcast live and most likely not recorded. George More O'Ferrall did the 1937 television adaptation too.

Alice at 8:30 on December 21 and 24

Some of her adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll.

Dramatised by Clemence Dane, with music by Richard Addinsell

Alice (Vivian Pickles)

White Rabbit (Erik Chitty)

Mad Hatter (Desmond Walter-Ellis)

March Hare (John Baker)

Dormouse (Gwyneth Lewis)

Caterpillar (Dorothy Stuart)

Dodo (John Roderick)

Mouse (Betty Petter)

Mock Turtle (Philip Stainton)

Gryphon (Milary Pritchard)

Ugly Duchess (Madge Brindley)

Cook (Miriam Karlin)

Adapted for television and produced by George More O'Ferrall

Information Sources 1, 2

3 notes

·

View notes