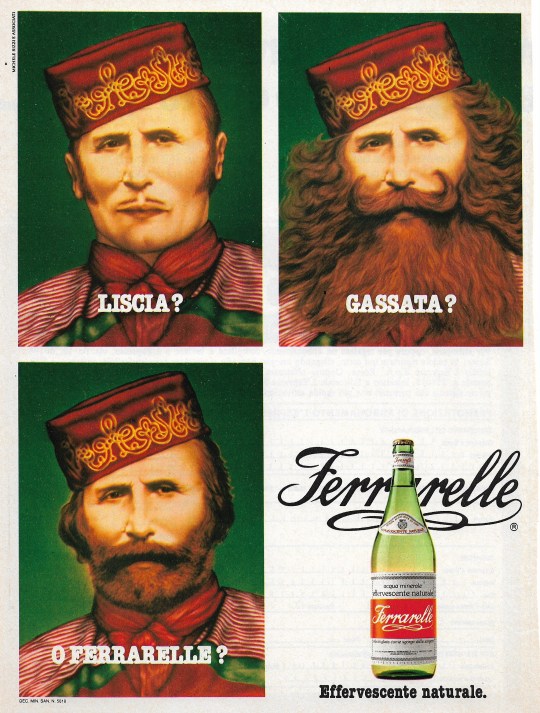

#giuseppe garibaldi

Text

ohisashiburi

#azur lane#all their al girls for valentines!!!!#duca degli abruzzi#abruzzi#giuseppe garibaldi#plymouth#ulrich von hutten#foch#bellona#manjuu#yostar#official art kinda??? idk

46 notes

·

View notes

Text

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

“ Attilio ed Emilio Bandiera erano figlioli di un contrammiraglio della marina austriaca, di cui essi stessi facevano parte, l'uno come alfiere di vascello e l'altro come alfiere di fregata. Non volendo servire l'Austria, dopo aver preso parte ad alcuni moti rivoluzionari, essi si erano ricoverati a Corfù. E in quel contatto con altri esuli in terra straniera; in quel comunicarsi continuo di aspirazioni e di speranze, più rincresceva loro l'inedia che l'esilio. Ond'è che decisero una spedizione arditissima, quasi folle per ardimento. Insieme a Ricciotti, a Moro e a pochi audacissimi, pensarono di compiere uno sbarco sulle coste di Calabria. Ivi avrebbero cercato di far rivoltare le popolazioni calabresi e, se fossero riesciti, di mettere in fiamme tutto il regno di Napoli.

Nel 1844, nella notte dal 12 al 13 giugno, i due fratelli Bandiera partirono per la spiaggia calabrese. Era in essi presentimento di morte. Quasi al momento di partire Nicola Ricciotti ed Emilio Bandiera così scrivevano a Garibaldi: « Se soccomberemo, dite ai nostri concittadini che imitino l'esempio, poiché la vita ci venne data per utilmente impiegarla; e la causa per la quale avremo combattuto e saremo morti, è la più pura, la più santa che mai abbia scaldato i petti degli uomini; essa è quella della libertà, della eguaglianza, della umanità, dell'indipendenza, dell'unità d'Italia ».

Erano buoni e sinceri: aveano soprattutto la giovanile ingenuità senza di che non è possibile compiere né tentare imprese come quella cui essi si avventuravano. La sera del 16 giugno il piccolo drappello sbarcò sulla costa calabrese, alla foce del fiume Nebo. Il luogo dello sbarco era tristissimo: ma la terra d'Italia parve a essi sacra e la baciarono all'arrivo. Il piccolo drappello, mal guidato, inesperto dei luoghi, aveva anche nel suo seno chi dovea tradirlo. Gli esuli speravano di trovare al loro arrivo popolazioni desiderose di rivolte: e trovarono l'ostilità e la indifferenza. Nella valle di San Giovanni in Fiore — paese già sacro alla leggenda religiosa — circuiti da soldati del re, dopo disperata lotta in cui parecchi morirono, dovettero arrendersi. Un mese dopo, i due fratelli Bandiera furono fucilati, il 25 luglio, in quella stessa terra da cui avevano sperato partisse il segnale della rivolta.

Mai nessuna morte fu più compianta della loro. Erano giovani, ricchi, di alto casato: avevano rinunziato con serenità superumana a tutte le gioie della vita. Aveano tutte le qualità per destare negli animi il compianto, e la loro morte fu una delle cose che più nocquero a Ferdinando II. “

---------

Brano tratto dal saggio breve Eroi (1898) raccolto in:

Francesco Saverio Nitti, Eroi e briganti, Edizioni Osanna (collana Biblioteca Federiciana n° 3), Venosa (PZ), 1987¹; pp. 18-19.

#leggere#letture#eroismo#citazioni#saggio storico#Storia#Francesco Saverio Nitti#fratelli Bandiera#Calabria#saggistica#filosofia della Storia#Attilio Bandiera#Emilio Bandiera#utopie#Storia del Risorgimento#patriottismo#regno di Napoli#esilio#Giuseppe Garibaldi#Unità d'Italia#utopismo#utopia#patria#questione meridionale#Italia meridionale#Mezzogiorno d'Italia#San Giovanni in Fiore#meridionalismo#libertà#Cosenza

14 notes

·

View notes

Text

27 notes

·

View notes

Text

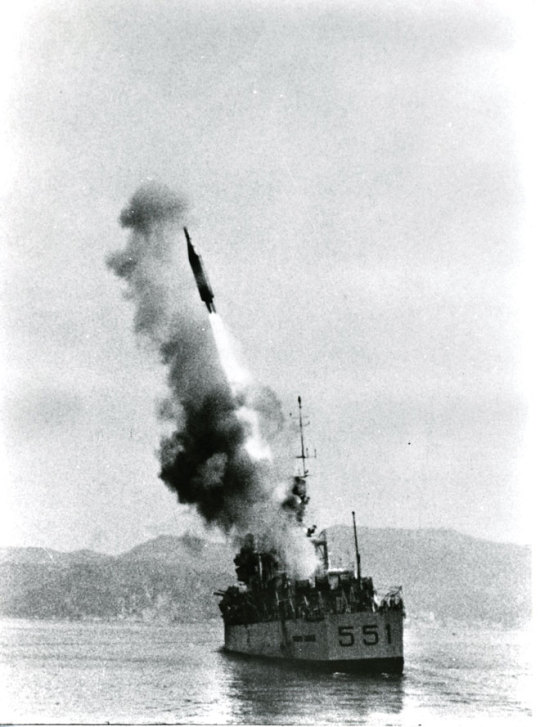

Italian light cruiser Giuseppe Garibaldi. Later conversion to guided missile cruiser included four launch tubes for Polaris ballistic missiles (never deployed in service).

16 notes

·

View notes

Photo

Noble Ivory Plumes

76 notes

·

View notes

Photo

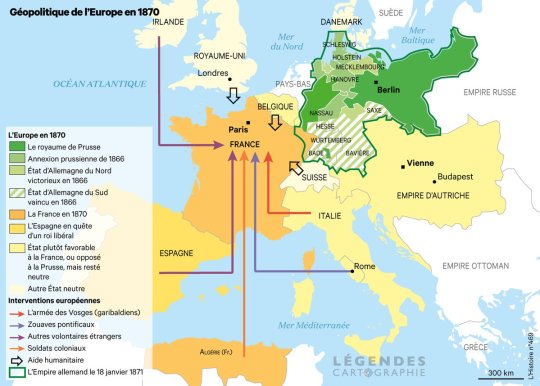

In 1870, Garibaldi aged 63 and accompanied by his two sons, offered his services to the French Republic which was threatened by the Prussian armies. The Battle of Dijon, won by the Garibaldians, is one of the only French victories of this war.

by @LegendesCarto

84 notes

·

View notes

Text

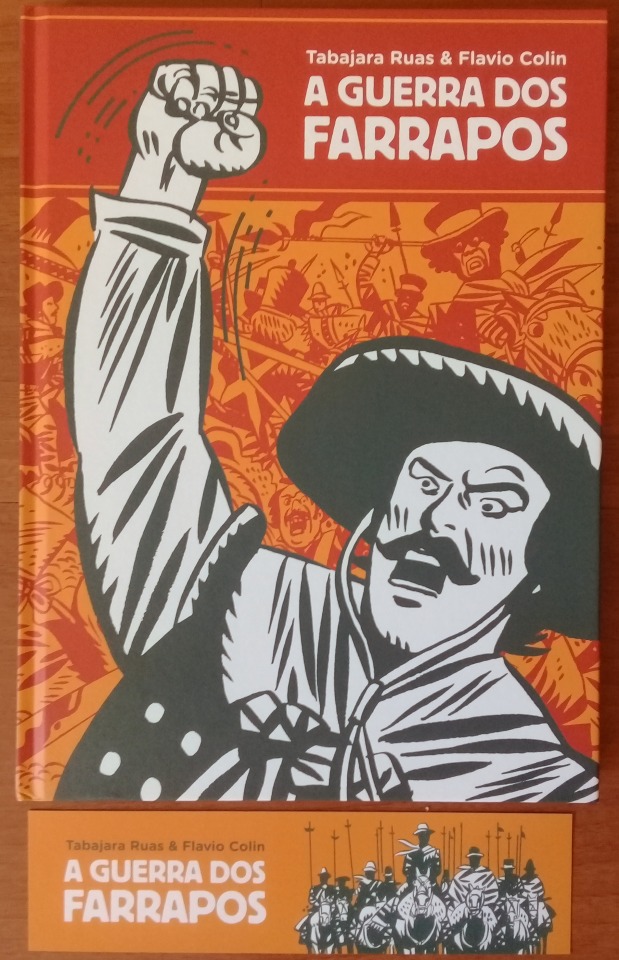

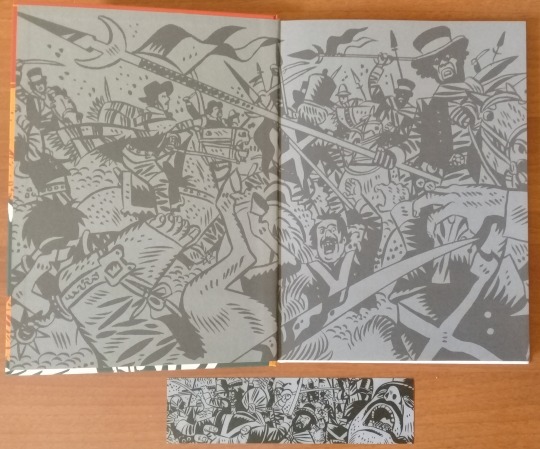

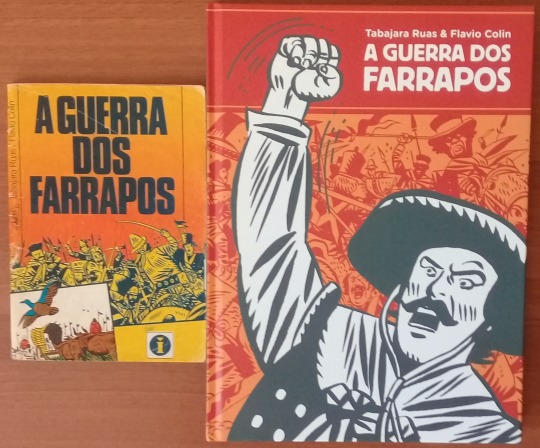

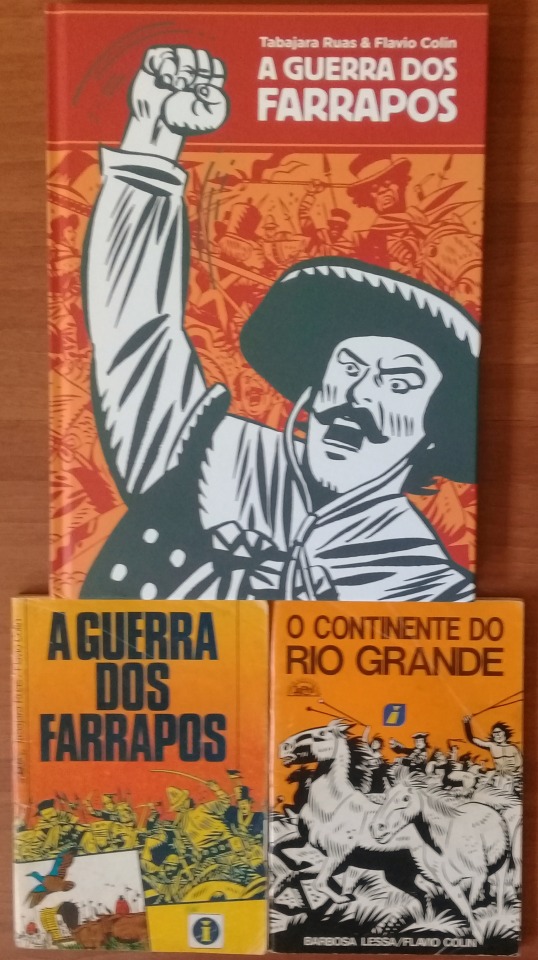

A Guerra dos Farrapos.

Comix Zone - 2022.

#comics#comix zone#guerra dos farrapos#brasil#brazil#rio grande do sul#revolução farroupilha#tabajara ruas#flavio colin#l&pm#ipiranga#bento gonçalves#duque de caxias#david canabarro#giuseppe garibaldi#anita garibaldi

2 notes

·

View notes

Photo

« First [sic] wife of Francesco Crispi. With him, she conspired for the sake of the unity of the Homeland. With him, she took part in the legendary Expedition of the Thousands. Sole woman in the immortal legion, she became its heroine. She enjoyed Mazzini’s trust and Garibaldi’s friendship. An example for Italian women of male patriotic virtues and gentle domestic virtues.»

Epitaph of Rose Montmasson, carved on her tombstone in Verano Cemetery, Rome [my translation]

Rose (also known as Rosalie and, more commonly in Italy, Rosalia) Montmasson was born on January 12th 1823 in Saint-Jorioz, a small village in the Haute-Savoie region, at that time still part of the Kingdom of Sardinia. She was fourth of five children and her parents, Gaspard and Jacqueline Pathoud, were humble farmers. As a child, Rose helped her parents both at home and in the fields, and received a simple education, she learnt to write, read and do maths.

In 1840, the death of her mother, aggravated the already unstable economic conditions of the family, forcing Rose to move to the more economically vibrant Torino in search of a job. Starting 1849, she worked as an ironer and, through her job, she met the Sicilian patriot and lawyer, Francesco Crispi (1818-1901). His first wife, Rosina D’Angelo, had died in 1839 due to complications in childbirth, after two short years of marriage. The baby, Tommaso, died a couple of hours later and, five months later, mother and son were followed by 2-years old Giuseppa, Francesco and Rosina’s first child. Following his wife and children’s deaths, Crispi became romantically involved with a Felicita Vella (called Ciuzza), with whom he fathered a son, Tommaso. Because of his liberal and democratic ideas as well as his active participation in the Sicilian revolution of 1848, Francesco Crispi had been forced to exile and his first destination was Piedmont.

Having met because Rose used to iron Francesco’s shirts, they started living together in 1850. Unfortunately, their cohabitation was soon disturbed when Felicita Vella moved into the same neighbourhood. Indeed, the scorned woman started harassing the couple, arriving to report Rose for mistreating young Tommaso.

Following the failed anti-Austrian uprising of 1853 in Milan, Crispi was once again forced to exile. He reached Genova and, from there, he sailed for Malta, where he was joined by Rose. On December 27th 1854 the two got married. Since, for the nth time, Francesco was compelled to abandon his asylum, they didn’t have enough time to plan the wedding and couldn’t, in that short time, provide the necessary documents. Because of this, no priest was willing to celebrate the wedding, until they convinced (for a fee) a wanderer Jesuit, Luigi Marchetti, to perform the ceremony. Only later, it would turn out Marchetti (who was also a patriot) had been previously interdicted and suspended a divinis, and this would later bear tragic consequences for Rose.

Three days later, Crispi sailed for London, while Rose stayed in La Valletta, waiting for the act of marriage to be registered in the parish of St. Publius and for the notary’s endorsement of the certificate. She then set out to join her husband in England, stopping at Saint-Jorioz to announce to her family she had finally got married (her father and siblings didn’t approve of her living together with a man who wasn’t her husband). At the beginning of 1855, she was finally in London. In the British capital, Rose navigated between befriending many of the fellow Sicilian exiles and patriots (like Giuseppe Mazzini) and taking care of her husband. As Tina Scalia (daughter of a couple of those refugees) would put it: to Rose wifely love consisted in being for Crispi “a cook, a laundress, and an errand girl”. Her devotion for her husband and his cause went beyond her household chores. The brave woman put her own life in danger by acting as a connection between Mazzini and his followers in France and elsewhere. She secretly conveyed his messages, plans and instructions, hiding the papers in haunches of game and smuggling them past customs officers and gendarmes. In 1856 the Crispis moved to Paris, and there Rose devoted herself to the logistical coordination of the Italian clandestine network. She didn’t even neglect to look after Francesco’s recently orphaned nephew, Felice Caratozzolo (son of Anna Serafina Crispi, also called Marianna), who had just reached Paris at the wish of his uncle, who wanted to provide the teen with a better future. Because of Francesco’s frequent trips, Rose found herself often alone. Felice proved to be an unruly kid, with no respect for rules and who didn’t acknowledge his aunt’s authority. At some point he even left the house and came back only when his uncle returned from his trip, and managed to convince his nephew to come back home. Luckily for Rose, her partner took her side when Marianna Crispi (who clearly only got her son’s side of her story) wrote his brother a letter lamenting her son’s mistreatment at the hands of Rose. Francesco answered that his wife took by heart the idea of taking care of Felice as he was her own child, spurring him to study and behave. Moreover, since she loved and feared her husband, she would have never done something which would have enraged him like mistreating Felice. As for Francesco, he regretted never having hit his nephew as it would have done him good.

In 1858, the Crispis, together with young Felice, had to leave France since Francesco had been suspected to be in league with Felice Orsini (the Italian patriot who had tried unsuccessfully to assassinate Napoleon III the year prior). They went back to London where he got again in touch with Mazzini. 1859 marked a turning point in Crispi’s patriotic experience. The Kingdom of Sardinia, together with Napoleon III’s France, had defeated the Austrian Empire. The Austrians had ceded Lombardy to France, whom, in turn, passed it to Sardinia. The year after Sardinia had exploited the situation and annexed the Duchy of Tuscany, the Duchy of Parma, the Duchy of Modena and Reggio, and the Papal Legations. Nice and Savoy were ceded to France as compensation for assisting the Sardinians. The outcome of the Second Italian War of Independence had suggested Crispi that, unlike what Mazzini (and Crispi with him) had advocated, perhaps Italy’s future was monarchic rather than republican.

From London the Crispi couple moved to Torino and Genova. In July 1859, Crispi reached Messina incognito, convinced that he could arrange an anti-Borbonic revolt with the support of the Sicilian mazziniani. The uprising (planned for October 4th) was delayed indefinitely. This convinced Crispi that a future revolt in Sicily needed the support of the population rather than committees and that a military expedition was fundamental to back up the insurrection.

In order to plan this uprising, in March 1860, Rose embarked on a steamboat headed for Messina to get in touch with Sicilian patriots Rosolino Pilo and Giovanni Corrao. She reached Malta to meet with fellow patriots Nicolò Fabrizi and Giorgio Tamajo with whom she exchanged information and letters she took with her when she returned to Genova.

Two months later, Rose embarked on the steamboat Piemonte headed once again for Sicily, the only (official) female member of the Expedition of the Thousand. Her husband had been against her participation, while Garibaldi, despite the initial veto, had given his consent (“Come then, if it pleases you. However bear it in your mind that you’re putting yourself in great risk and peril, and I won’t answer to it”). In Sicily, armed with a gun, she risked her life to fight in Marsala, Calatafimi and Palermo. She also helped tend to the injured soldiers, quickly becoming a familiar and dear figure. The Sicilians quickly renamed her Rosalia, after St. Rosalia, the much beloved saint patron of Palermo, and with this name, she would be remembered.

If Rose thought the desired and fought for the Unification of Italy in 1861 would mark the beginning of a much happier and more secure future, she quickly realized how wrong she was. The only one who benefited from it was her husband. The couple moved back to Torino and then Firenze, where they spent their last period of relative happiness. In 1861 Francesco was elected deputy of the Parliament of the newborn Kingdom of Italy (and would later become one of its Prime Ministers) and quickly turned his back on his republican ideal becoming a staunch monarchist. Rose (as well as many of his old friends) must have seen it as a betrayal and it must have made their relationship even rockier. Crispi didn’t just betray her in terms of shared political ideals, but also in more personal terms. He had various flirts with women much younger than his wife and even fathered illegitimate children with them. He reached his worst in 1878 when, after repudiating Rose (claiming their Maltese marriage was irregular), he married Filomena (Lina) Barbagallo, with whom he had a child five years prior. This caused such an uproar (and the accusation of bigamy) that, during a public event, Queen Margherita refused to shake his hand. As it came to light the fact that brother Luigi Marchetti, who had performed the wedding ceremony, had been interdicted and thus Rose and Francesco’s marriage was null.

The betrayed woman moved to a modest house in Rome, where the couple had previously moved when the city was declared Capital of the Kingdom in 1871, and the whole court had moved there.

Rose spent the last part of her life in financial hardship, economically helped by her friends. Through common friends, Agostino Bertani and Giorgio Tamajo, she reached an agreement with her former husband, who agreed to pay her a life annuity. When Crispi died in 1901, Rose (as a former Garibaldina) was offered a meagre Royal pension, who allowed her to live her last couple years in semi poverty.

Rose Montmasson died in Rome on November 10th 1904 after suffering from a stroke. She was 81. Since she couldn’t afford it, she was buried in a simple grave, freely granted by the Campo Verano Cemetery. According to her wishes, she was dressed up with a red shirt (symbol of the Thousands), and her medals were displayed on a pillow placed before her coffin. Her funeral (a secular ceremony) was attended by many Garibaldini, and people she had personally helped during the Expedition, but no representative (except from Senator Francesco Cucchi, who had personally known her during the Sicilian adventure) of the Nation she had helped made.

Sources

- CASALINI Fabio, Rosalia Montmasson, l’unica donna tra i Mille di Garibaldi

- FERRI Marco, Rosalia Montmasson;

- ODDO Giacomo, I mille di Marsala: scene rivoluzionarie;

- PAGLIUSO Antonio, Rosalia Montmasson: la Storia dell’unica Donna tra i Mille di Garibaldi;

- PALADINO Francesco, Crispi, Francesco;

- PALAMENGHI CRISPI Giulio, Rose Montmasson;

- Rosalia Montmasson;

- Rose Montmasson Crispi;

- ZAZZERI Angelica, Montmasson, Rosalie

#historicwomendaily#women#history#women in history#historical women#rose montmasson#francesco crispi#giuseppe garibaldi#spedizione dei mille#contemporary sicily#people of sicily#women of sicily#myedit#historyedit

11 notes

·

View notes

Text

ITALIA

2 notes

·

View notes

Text

ohisashiburi.

24 notes

·

View notes

Text

3 notes

·

View notes

Text

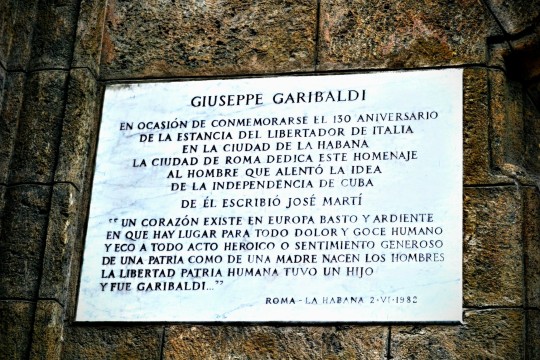

IN EUROPA ESISTE UN CUORE GRANDE E ARDENTE IN CUI C'È SPAZIO PER TUTTO IL DOLORE E IL GODIMENTO UMANO ED ECO PER OGNI ATTO EROICO O SENTIMENTO GENEROSO.

COME DA UNA MADRE NASCONO GLI UOMINI, LIBERTÀ, LA PATRIA UMANA, HA AVUTO UN FIGLIO ED ERA GARIBALDI."

José Martí

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Grande Fratello Mirko Brunetti accusa Giuseppe Garibaldi di incoerenza e di essere un giocatore

#grandefratello. Nuovo anno vecchie accuse al Grande Fratello. Infatti è tornato di nuovo Mirko Brunetti per confrontarsi con Gisueppe Garibaldi, che l'ha accusato di essere incoerente e di essere un giocatore. Inultile dirvi che il calabro l'ha presa ver

E veniamo adesso a parlarvi di Mirko Brunetti che a quanto pare una volta uscito dalla csa del Grande Fratello ha rivisto molte delle sue posizioni in particolare nei confronti di Giuseppe Garibaldi, che dentro la casa era un suo amico…adesso invece pensa che che sia uno stratega, ossia che tutto quello che fa , lo stia facendo con un secondo fine. Già la settimana scorsa gli aveva detto che…

View On WordPress

0 notes