#global superpower status

Text

World map of Mareinia, with all the meganations labeled. Meganations are a relatively recent invention, and although these are the official borders, there are plenty of independent regions that reject the meganations' claimed sovereignty over them.

#mareinia#planet#culture#the arudeb regions are a good example of what the political landscape looked like before ~100 years ago#anyway mesna mas is stast's greatest threat to their status as a global superpower so they hate them real bad

4 notes

·

View notes

Text

Thursday, December 7.

There are apples, and then there are apples.

And this would be the latter. In fact, apples really don't come much bigger. If this particularly large apple were a nation-state, it would have the tenth-largest economy in the world. Which is pretty good, for an apple.

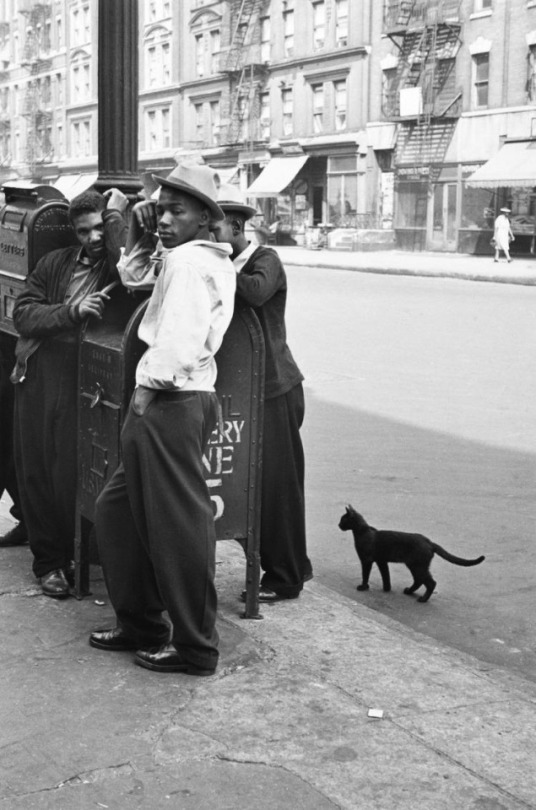

But this is New York City, after all, and its reputation precedes it. Sometimes described as the world's most important city, sometimes as the capital of the world, it truly is all things at once. It is defined by its fevered, electric pace of life. A global city in which 800 languages are spoken, it is a cultural, historical, sporting, and political superpower. It is, famously, The City That Never Sleeps. Better still, it enforces a right-to-shelter law ensuring, in the legislature, a bed and roof for anyone who needs one, regardless of immigration status.

Today it transpires that #new york is trending. A lot is going on, so take your time. Enjoy it.

@semioticapocalypse

#today on tumblr#new york#new york city#nyc#nyc aesthetic#nyc subway#nyc street photography#manhattan#brooklyn#nyc girl#new york city subways#nyclife#travel#travel destinations#explore#city life#culture

512 notes

·

View notes

Text

The biggest threat to the United States is not China or Russia or other "external threats," said Max Boot. It's "our own political dysfunction." The U.S. remains fundamentally strong, with the world's biggest and most resilient economy, the most powerful military, and 50 allies, compared with a handful for China and Russia. China's once-booming economy has stagnated, due to poor central planning and an aging and shrinking population. We remain the world's only true superpower and an "indispensable nation," keeping rogue actors like Vladimir Putin and Iran in check. But extreme partisan warfare and a growing isolationist movement have put us on the road to abdicating that critical role. A divided Congress cannot even pass a budget, or agree on military aid to embattled allies Israel and Ukraine. If Donald Trump and his "American First" brigade regains the White House, he'll likely abandon Ukraine, pull the U.S. out of NATO, alienate allies, and cripple our nation's global power. A host of enemies, including Nazi Germany, al Qaida, the Soviet Union, Russia, and China have been unable to cripple the U.S. and demote us to second-class status. But Americans may succeed where "others have failed."

THE WEEK November 24, 2023

287 notes

·

View notes

Text

BERLIN – Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine on Feb. 24, 2022, changed everything for Ukraine, for Europe, and for global politics. The world entered a new era of great-power rivalry in which war could no longer be excluded. Apart from the immediate victims, Russia’s aggression most concerned Europe. A great power seeking to extinguish an independent smaller country by force challenges the core principles upon which the European order of states has organized itself for decades.

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s war stands in stark contrast to the self-dissolution of the Warsaw Pact and the Soviet Union, which occurred in a largely non-violent manner. Since the “Gorbachev miracle” – when the Soviet Union started pursuing liberalizing reforms in the 1980s – Europeans had begun to imagine that Immanuel Kant’s vision of perpetual peace on the continent might be possible. It was not.

The problem was that many Russian elites’ interpretation of the globally significant events of the late 1980s could not be more opposed to Kant’s idea. They saw the demise of the great Russian empire (which the Soviets had recreated) as a devastating defeat. Though they had no choice but to accept the humiliation, they told themselves they would do so only temporarily until the balance of power had changed. Then the great historical revision could begin.

Thus, the 2022 attack on Ukraine should be viewed as merely the most ambitious of the revisionist wars Russia has waged since Putin came to power. We can expect many more, especially if Donald Trump returns to the White House and effectively withdraws the United States from NATO.

But Putin’s latest war not only changed the rules of co-existence on the European continent; it also changed the global order. By triggering a sweeping re-militarization of foreign policy, the war has seemingly returned us to a time, deep in the twentieth century, when wars of conquest were a staple of the great-power toolkit. Now, like then, might makes right.

Even during the decades-long Cold War, there was no risk of a “new Sarajevo” – the political fuse that detonated the first World War – because the standoff between two nuclear superpowers subordinated all other interests, ideologies, and political conflicts. What mattered were the superpowers’ own claims to power and stability within the territories they controlled. The risk of another world war had been replaced by the risk of mutual assured destruction, which functioned as an automatic stabilizer within the bipolar system of the Cold War.

Behind Putin’s war on Ukraine is the neo-imperial goal that many Russian elites share: to make Russia great again by reversing the results of the collapse of the Soviet Union. On December 8, 1991, the presidents of Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine met in Białowieża National Park and agreed to dissolve the Soviet Union, reducing a “superpower” to a regional (albeit still nuclear-armed) power in the form of the Russian Federation.

No, Putin does not want to revive the communist Soviet Union. Today’s Russian elite knows that the Soviet system could not be sustained. Putin has embraced autocracy, oligarchy, and empire to restore Russia’s status as a global power, but he also knows that Russia lacks the economic and technological prerequisites to achieve this on its own.

For its part, Ukraine wants to join the West – meaning the European Union and the transatlantic security community of NATO. Should it succeed, it would probably be lost to Russia for good, and its own embrace of Western values would pose a grave danger to Putin’s regime. Ukraine’s modernization would lead Russians to ask why their political system has consistently failed to achieve similar results. From a “Great Russia” perspective, it would compound the disaster of 1991. That is why the stakes in Ukraine are so high, and why it is so hard to imagine the conflict ending through compromise.

Even in the case of an armistice along the frozen front line, neither Russia nor Ukraine will distance themselves politically from their true war aims. The Kremlin will not give up on the complete conquest and subjugation (if not annexation) of Ukraine, and Ukraine will not abandon its goal of liberating all its territory (including Crimea) and joining the EU and NATO. An armistice thus would be a volatile interim solution involving the defense of a highly dangerous “line of control” on which Ukraine’s freedom and Europe’s security depend.

Since Russia no longer has the economic, military, and technological capabilities to compete for the top spot on the world stage, its only option is to become a permanent junior partner to China, implying quasi-voluntary submission under a kind of second Mongol vassalage. Let us not forget: Russia survived two attacks from the West in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries – by Napoleon and Hitler, respectively. The only invaders who have conquered it were the Mongols in the winter of 1237-38. Throughout Russia’s history, its vulnerability in the east has had far-reaching consequences.

The main geopolitical divide of the twenty-first century will center on the Sino-American rivalry. Though Russia will hold a junior position, it nonetheless will play an important role as a supplier of raw materials and – owing to its dreams of empire – as a permanent security risk. Whether this will be enough to satisfy Russian elites’ self-image is an open question.

21 notes

·

View notes

Text

one of the biggest reasons why alfred is so smiley, goofy, happy-go-lucky, devil-may-care during the 19th through 21st centuries, (besides deciding since before 1776 that he was going to be completely contrarian to arthur in his outlooks) is that he’s been through the wringer for the past hundred years already. give the guy a break!

spending your formative years (or the country equivalent of a ‘childhood’, anyway) educating yourself deeply on politics, fighting for independence, then fighting again to keep your nation together, and then trying to expand throughout the rest of the continent, while dealing with crazy winters and starvation and swathes of diseases… well.

alfred grew up with the expectation of perfection under england, and even after becoming free he still had to raise himself by the bootstraps. help create a government with his people, for his people, and hope and pray to whatever deity was out there that america could survive. and those first 100 years certainly were not sunshine and rainbows — pictures of alfred’s youth show everything except smiles. he wears melancholy expressions that don’t suit his face.

battling for your place on the world stage is hard enough, but to become a self-made, global superpower on top of it? alfred grows in spades, and by the time the industrial revolution comes around, and his house is the most bustling on the entire planet, and the gold rush comes and goes— that constant work and isolationism has paid off. he loosens up a little. he can smile now. relax a little! eat in excess knowing there will always be food on the table.

that’s when he finally gets to live out the years of childlike ease he never truly got to indulge in: to laugh and be merry without a care in the world. momentary ill spell during the great depression aside, the great wars later only solidify america’s place as the strongest in the world. the other countries wouldn’t dare admit it, but alfred’s self-proclaimed epithet of ‘hero’ is not without cause and reason, and not without hard proof. (and besides, he deserves a little gloating after all this time, doesn’t he?)

ivan had threatened his status in the hierarchy for a while there, and 45 years of foolhardy, workaholic america stepped out of the shadows again. but again, alfred surpasses the literal and proverbial soviet wall. and this time it isn’t just the world he has in his palms, but outer space, too — he has the moon and the stars and a damn space station.

finally, on top— finally, he doesn’t have to battle tooth and nail just to survive. instead, maybe he’ll set a whoopie cushion on françois’ chair at the next meeting, or order everything off the mcdonald’s menu tonight just ‘cause he can, or maybe even get matt to film him doing some outrageously ridiculous parkour—

that’s the beauty of it: it’s enjoyable to let go, act as immature and carefree as you want, knowing you’re at the top of the food chain. the others have gotten used to boy scout america, to the silly superhero alfred — they’ve definitely forgotten how scary and smart and cutthroat and frankly bloodthirsty he is when he gets serious. the america that lies asleep beneath the surface, the sleeping dog that you’d better hope you don’t wake up.

and, hell— his people chose him. his people left the other nations for him. left their homelands to stay at his house. that’s a testament to the unshakeable empire he’s built up, right? the others should be following his lead.

so he’ll act as he pleases, screw all the manners and customs and old-world european way of doing things — the freedom-loving rebel bastard that he still is, deep down.

al’s earned it, after all!

#UP LATE AT NIGHT DOING ALFRED CHARACTER STUDIES#bunnie's coffeehouse#hetalia#alfred f jones#aph america#hws america#/ long post#RAMBLE INCOMING#really i think alfred had a huge come-to moment during the 1800s-2000s#as we kind of see in the industrial age arc…#and some of the america and canada stories in world stars too you can just totally see in his early years how dead serious he was !!#yearning for greatness and the stability and renown that comes with that. unable to have more of a 'childhood' like canada.#soon enough he realizes he’s become number 1 in like everything. but at the cost of being deeply entrenched in his work#he hasnt had time to do much else. and thats when he knows he can /rest/ and i imagine that’s when he truly indulges in his childlike wonde#like we SEE how hard of a worker he is… how many fucked up odds he’s overcome. America has conquered them all#he is truly the epitome of veni vidi vici#veni vidi vici & THEN HE SCREWS AROUND MANUFACTURING MEMES & CHUGGING COLA FOR THE BETTER PART OF A CENTURY. GOOD FOR YOU AL YOU DESERVE IT#god i love him

33 notes

·

View notes

Text

If you had to capture Silicon Valley’s dominant ideology in a single anecdote, you might look first to Mark Zuckerberg, sitting in the blue glow of his computer some 20 years ago, chatting with a friend about how his new website, TheFacebook, had given him access to reams of personal information about his fellow students:

Zuckerberg: Yeah so if you ever need info about anyone at Harvard

Zuckerberg: Just ask.

Zuckerberg: I have over 4,000 emails, pictures, addresses, SNS

Friend: What? How’d you manage that one?

Zuckerberg: People just submitted it.

Zuckerberg: I don’t know why.

Zuckerberg: They “trust me”

Zuckerberg: Dumb fucks.

That conversation—later revealed through leaked chat records—was soon followed by another that was just as telling, if better mannered. At a now-famous Christmas party in 2007, Zuckerberg first met Sheryl Sandberg, his eventual chief operating officer, who with Zuckerberg would transform the platform into a digital imperialist superpower. There, Zuckerberg, who in Facebook’s early days had adopted the mantra “Company over country,” explained to Sandberg that he wanted every American with an internet connection to have a Facebook account. For Sandberg, who once told a colleague that she’d been “put on this planet to scale organizations,” that turned out to be the perfect mission.

Facebook (now Meta) has become an avatar of all that is wrong with Silicon Valley. Its self-interested role in spreading global disinformation is an ongoing crisis. Recall, too, the company’s secret mood-manipulation experiment in 2012, which deliberately tinkered with what users saw in their News Feed in order to measure how Facebook could influence people’s emotional states without their knowledge. Or its participation in inciting genocide in Myanmar in 2017. Or its use as a clubhouse for planning and executing the January 6, 2021, insurrection. (In Facebook’s early days, Zuckerberg listed “revolutions” among his interests. This was around the time that he had a business card printed with I’M CEO, BITCH.)

And yet, to a remarkable degree, Facebook’s way of doing business remains the norm for the tech industry as a whole, even as other social platforms (TikTok) and technological developments (artificial intelligence) eclipse Facebook in cultural relevance.

To worship at the altar of mega-scale and to convince yourself that you should be the one making world-historic decisions on behalf of a global citizenry that did not elect you and may not share your values or lack thereof, you have to dispense with numerous inconveniences—humility and nuance among them. Many titans of Silicon Valley have made these trade-offs repeatedly. YouTube (owned by Google), Instagram (owned by Meta), and Twitter (which Elon Musk insists on calling X) have been as damaging to individual rights, civil society, and global democracy as Facebook was and is. Considering the way that generative AI is now being developed throughout Silicon Valley, we should brace for that damage to be multiplied many times over in the years ahead.

The behavior of these companies and the people who run them is often hypocritical, greedy, and status-obsessed. But underlying these venalities is something more dangerous, a clear and coherent ideology that is seldom called out for what it is: authoritarian technocracy. As the most powerful companies in Silicon Valley have matured, this ideology has only grown stronger, more self-righteous, more delusional, and—in the face of rising criticism—more aggrieved.

The new technocrats are ostentatious in their use of language that appeals to Enlightenment values—reason, progress, freedom—but in fact they are leading an antidemocratic, illiberal movement. Many of them profess unconditional support for free speech, but are vindictive toward those who say things that do not flatter them. They tend to hold eccentric beliefs: that technological progress of any kind is unreservedly and inherently good; that you should always build it, simply because you can; that frictionless information flow is the highest value regardless of the information’s quality; that privacy is an archaic concept; that we should welcome the day when machine intelligence surpasses our own. And above all, that their power should be unconstrained. The systems they’ve built or are building—to rewire communications, remake human social networks, insinuate artificial intelligence into daily life, and more—impose these beliefs on the population, which is neither consulted nor, usually, meaningfully informed. All this, and they still attempt to perpetuate the absurd myth that they are the swashbuckling underdogs.

Comparisons between Silicon Valley and Wall Street or Washington, D.C., are commonplace, and you can see why—all are power centers, and all are magnets for people whose ambition too often outstrips their humanity. But Silicon Valley’s influence easily exceeds that of Wall Street and Washington. It is reengineering society more profoundly than any other power center in any other era since perhaps the days of the New Deal. Many Americans fret—rightfully—about the rising authoritarianism among MAGA Republicans, but they risk ignoring another ascendant force for illiberalism: the tantrum-prone and immensely powerful kings of tech.

The Shakespearean drama that unfolded late last year at OpenAI underscores the extent to which the worst of Facebook’s “move fast and break things” mentality has been internalized and celebrated in Silicon Valley. OpenAI was founded, in 2015, as a nonprofit dedicated to bringing artificial general intelligence into the world in a way that would serve the public good. Underlying its formation was the belief that the technology was too powerful and too dangerous to be developed with commercial motives alone.

But in 2019, as the technology began to startle even the people who were working on it with the speed at which it was advancing, the company added a for-profit arm to raise more capital. Microsoft invested $1 billion at first, then many billions of dollars more. Then, this past fall, the company’s CEO, Sam Altman, was fired then quickly rehired, in a whiplash spectacle that signaled a demolition of OpenAI’s previously established safeguards against putting company over country. Those who wanted Altman out reportedly believed that he was too heavily prioritizing the pace of development over safety. But Microsoft’s response—an offer to bring on Altman and anyone else from OpenAI to re-create his team there—started a game of chicken that led to Altman’s reinstatement. The whole incident was messy, and Altman may well be the right person for the job, but the message was clear: The pursuit of scale and profit won decisively over safety concerns and public accountability.

Silicon Valley still attracts many immensely talented people who strive to do good, and who are working to realize the best possible version of a more connected, data-rich global society. Even the most deleterious companies have built some wonderful tools. But these tools, at scale, are also systems of manipulation and control. They promise community but sow division; claim to champion truth but spread lies; wrap themselves in concepts such as empowerment and liberty but surveil us relentlessly. The values that win out tend to be the ones that rob us of agency and keep us addicted to our feeds.

The theoretical promise of AI is as hopeful as the promise of social media once was, and as dazzling as its most partisan architects project. AI really could cure numerous diseases. It really could transform scholarship and unearth lost knowledge. Except that Silicon Valley, under the sway of its worst technocratic impulses, is following the playbook established in the mass scaling and monopolization of the social web. OpenAI, Microsoft, Google, and other corporations leading the way in AI development are not focusing on the areas of greatest public or epistemological need, and they are certainly not operating with any degree of transparency or caution. Instead they are engaged in a race to build faster and maximize profit.

None of this happens without the underlying technocratic philosophy of inevitability—that is, the idea that if you can build something new, you must. “In a properly functioning world, I think this should be a project of governments,” Altman told my colleague Ross Andersen last year, referring to OpenAI’s attempts to develop artificial general intelligence. But Altman was going to keep building it himself anyway. Or, as Zuckerberg put it to The New Yorker many years ago: “Isn’t it, like, inevitable that there would be a huge social network of people? … If we didn’t do this someone else would have done it.”

Technocracy first blossomed as a political ideology after World War I, among a small group of scientists and engineers in New York City who wanted a new social structure to replace representative democracy, putting the technological elite in charge. Though their movement floundered politically—people ended up liking President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal better—it had more success intellectually, entering the zeitgeist alongside modernism in art and literature, which shared some of its values. The American poet Ezra Pound’s modernist slogan “Make it new” easily could have doubled as a mantra for the technocrats. A parallel movement was that of the Italian futurists, led by figures such as the poet F. T. Marinetti, who used maxims like “March, don’t molder” and “Creation, not contemplation.”

The ethos for technocrats and futurists alike was action for its own sake. “We are not satisfied to roam in a garden closed in by dark cypresses, bending over ruins and mossy antiques,” Marinetti said in a 1929 speech. “We believe that Italy’s only worthy tradition is never to have had a tradition.” Prominent futurists took their zeal for technology, action, and speed and eventually transformed it into fascism. Marinetti followed his Manifesto of Futurism (1909) with his Fascist Manifesto (1919). His friend Pound was infatuated with Benito Mussolini and collaborated with his regime to host a radio show in which the poet promoted fascism, gushed over Mein Kampf, and praised both Mussolini and Adolf Hitler. The evolution of futurism into fascism wasn’t inevitable—many of Pound’s friends grew to fear him, or thought he had lost his mind—but it does show how, during a time of social unrest, a cultural movement based on the radical rejection of tradition and history, and tinged with aggrievement, can become a political ideology.

In October, the venture capitalist and technocrat Marc Andreessen published on his firm’s website a stream-of-consciousness document he called “The Techno-Optimist Manifesto,” a 5,000-word ideological cocktail that eerily recalls, and specifically credits, Italian futurists such as Marinetti. Andreessen is, in addition to being one of Silicon Valley’s most influential billionaire investors, notorious for being thin-skinned and obstreperous, and despite the invocation of optimism in the title, the essay seems driven in part by his sense of resentment that the technologies he and his predecessors have advanced are no longer “properly glorified.” It is a revealing document, representative of the worldview that he and his fellow technocrats are advancing.

Andreessen writes that there is “no material problem,” including those caused by technology, that “cannot be solved with more technology.” He writes that technology should not merely be always advancing, but always accelerating in its advancement “to ensure the techno-capital upward spiral continues forever.” And he excoriates what he calls campaigns against technology, under names such as “tech ethics” and “existential risk.”

Or take what might be considered the Apostles’ Creed of his emerging political movement:

We believe we should place intelligence and energy in a positive feedback loop, and drive them both to infinity …

We believe in adventure. Undertaking the Hero’s Journey, rebelling against the status quo, mapping uncharted territory, conquering dragons, and bringing home the spoils for our community …

We believe in nature, but we also believe in overcoming nature. We are not primitives, cowering in fear of the lightning bolt. We are the apex predator; the lightning works for us.

Andreessen identifies several “patron saints” of his movement, Marinetti among them. He quotes from the Manifesto of Futurism, swapping out Marinetti’s “poetry” for “technology”:

Beauty exists only in struggle. There is no masterpiece that has not an aggressive character. Technology must be a violent assault on the forces of the unknown, to force them to bow before man.

To be clear, the Andreessen manifesto is not a fascist document, but it is an extremist one. He takes a reasonable position—that technology, on the whole, has dramatically improved human life—and warps it to reach the absurd conclusion that any attempt to restrain technological development under any circumstances is despicable. This position, if viewed uncynically, makes sense only as a religious conviction, and in practice it serves only to absolve him and the other Silicon Valley giants of any moral or civic duty to do anything but make new things that will enrich them, without consideration of the social costs, or of history. Andreessen also identifies a list of enemies and “zombie ideas” that he calls upon his followers to defeat, among them “institutions” and “tradition.”

“Our enemy,” Andreessen writes, is “the know-it-all credentialed expert worldview, indulging in abstract theories, luxury beliefs, social engineering, disconnected from the real world, delusional, unelected, and unaccountable—playing God with everyone else’s lives, with total insulation from the consequences.”

The irony is that this description very closely fits Andreessen and other Silicon Valley elites. The world that they have brought into being over the past two decades is unquestionably a world of reckless social engineering, without consequence for its architects, who foist their own abstract theories and luxury beliefs on all of us.

Some of the individual principles Andreessen advances in his manifesto are anodyne. But its overarching radicalism, given his standing and power, should make you sit up straight. Key figures in Silicon Valley, including Musk, have clearly warmed to illiberal ideas in recent years. In 2020, Donald Trump’s vote share in Silicon Valley was 23 percent—small, but higher than the 20 percent he received in 2016.

The main dangers of authoritarian technocracy are not at this point political, at least not in the traditional sense. Still, a select few already have authoritarian control, more or less, to establish the digital world’s rules and cultural norms, which can be as potent as political power.

In 1961, in his farewell address, President Dwight Eisenhower warned the nation about the dangers of a coming technocracy. “In holding scientific research and discovery in respect, as we should,” he said, “we must also be alert to the equal and opposite danger that public policy could itself become the captive of a scientific-technological elite. It is the task of statesmanship to mold, to balance, and to integrate these and other forces, new and old, within the principles of our democratic system—ever aiming toward the supreme goals of our free society.”

Eight years later, the country’s first computers were connected to ARPANET, a precursor to the World Wide Web, which became broadly available in 1993. Back then, Silicon Valley was regarded as a utopia for ambitious capitalists and optimistic inventors with original ideas who wanted to change the world, unencumbered by bureaucracy or tradition, working at the speed of the internet (14.4 kilobits per second in those days). This culture had its flaws even at the start, but it was also imaginative in a distinctly American way, and it led to the creation of transformative, sometimes even dumbfoundingly beautiful hardware and software.

For a long time, I tended to be more on Andreessen’s end of the spectrum regarding tech regulation. I believed that the social web could still be a net good and that, given enough time, the values that best served the public interest would naturally win out. I resisted the notion that regulating the social web was necessary at all, in part because I was not (and am still not) convinced that the government can do so without itself causing harm (the European model of regulation, including laws such as the so-called right to be forgotten, is deeply inconsistent with free-press protections in America, and poses dangers to the public’s right to know). I’d much prefer to see market competition as a force for technological improvement and the betterment of society.

But in recent years, it has become clear that regulation is needed, not least because the rise of technocracy proves that Silicon Valley’s leaders simply will not act in the public’s best interest. Much should be done to protect children from the hazards of social media, and to break up monopolies and oligopolies that damage society, and more. At the same time, I believe that regulation alone will not be enough to meaningfully address the cultural rot that the new technocrats are spreading.

Universities should reclaim their proper standing as leaders in developing world-changing technologies for the good of humankind. (Harvard, Stanford, and MIT could invest in creating a consortium for such an effort—their endowments are worth roughly $110 billion combined.)

Individuals will have to lead the way, too. You may not be able to entirely give up social media, or reject your workplace’s surveillance software—you may not even want to opt out of these things. But there is extraordinary power in defining ideals, and we can all begin to do that—for ourselves; for our networks of actual, real-life friends; for our schools; for our places of worship. We would be wise to develop more sophisticated shared norms for debating and deciding how we use invasive technology interpersonally and within our communities. That should include challenging existing norms about the use of apps and YouTube in classrooms, the ubiquity of smartphones in adolescent hands, and widespread disregard for individual privacy. People who believe that we all deserve better will need to step up to lead such efforts.

Our children are not data sets waiting to be quantified, tracked, and sold. Our intellectual output is not a mere training manual for the AI that will be used to mimic and plagiarize us. Our lives are meant not to be optimized through a screen, but to be lived—in all of our messy, tree-climbing, night-swimming, adventuresome glory. We are all better versions of ourselves when we are not tweeting or clicking “Like” or scrolling, scrolling, scrolling.

Technocrats are right that technology is a key to making the world better. But first we must describe the world as we wish it to be—the problems we wish to solve in the public interest, and in accordance with the values and rights that advance human dignity, equality, freedom, privacy, health, and happiness. And we must insist that the leaders of institutions that represent us—large and small—use technology in ways that reflect what is good for individuals and society, and not just what enriches technocrats.

We do not have to live in the world the new technocrats are designing for us. We do not have to acquiesce to their growing project of dehumanization and data mining. Each of us has agency.

No more “build it because we can.” No more algorithmic feedbags. No more infrastructure designed to make the people less powerful and the powerful more controlling. Every day we vote with our attention; it is precious, and desperately wanted by those who will use it against us for their own profit and political goals. Don’t let them.

23 notes

·

View notes

Text

The other night I had drinks with coworkers. I increasingly dislike all of them. The topic of the Coronation came up, unsurprisingly. One of my colleagues said ‘we should have done what the French did’, and me and one other kinda went ‘haha yeah!’ and I thought for a moment that maybe I wouldn’t be in the political minority, even if these people will never be dedicated to the pursuit of global communism. My boss said, unironically, ‘what did the French do?’

Now I knew this was a bad sign, but me and person who initially referenced the French Revolution tried to sort of extol a few key details of the abolition of monarchy and formation of the First Republic, with probably disproportionate attention on the Terror. But anyway, my boss said something like ‘my knowledge of history isn’t great before the war’, and I asked genuinely ‘which war?’, which was interpreted as a sarcastic joke.

Anyway, this led to talking about WWII. Someone said something like ‘well the Second World War was unique among wars because it was essentially good versus evil’, to which I interjected ‘well kinda more like evil versus evil, right’. The response to this, from all three of my colleagues in the conversation, was ‘oh right, the Soviets’. I think if you follow this blog (or especially my politcal sideblog) you may have encountered my generalised view of the Soviet Union. Keeping in mind that it was Gevurah ShebeHod (since most of my personal posts seem to mark some significant point on the Hebrew calendar), I tried to rein in my response, and just said ‘interesting that when I mention the evil superpowers of the Allies in WWII you say the Soviets but not Britain or America.’ So the following dialogue came out of this:

Colleague (with history degree): Well I don’t know much about Roosevelt’s policy or ideological allignment...

Me: Well he kinda committed genocide against the Navajo.

C(whd): ...Churchill may have been a shitty guy...

Me: Well he kinda committed genocide against India and Palestine.

C(whd): ...But Britain essentially had to go to war with the Nazis.

Me: To safeguard their material interests though, right, not for the altruism of saving the brutalised people of Europe.

C(whd): Well Britain didn’t have any interests in Poland.

Me: Well I think upholding a status quo is a very strong material interest for imperial Europe, but I was really talking about North Africa and the Middle East.

C(whd): But those regions weren’t threatened by Germany, but by Italy.

Me: Do you honestly think Churchill or whoever was thinking in such a two-dimensional way as to see these powers in a vacuum? [I wish I’d said ‘I think they were pretty threatened by Britain too, and remain so.’]

Colleague who’d followed silently: Well every government has done horrible things at some point.

Me: And yet when I mentioned evil versus evil, you all glanced right past the genocidal empires of Britain and America to look at the Soviets.

Boss (unironically): I didn’t think when I mentioned the war that we’d be talking so much about genocide.

Now I wanna leave this on a couple crucial points. One is that I am very overt about being Jewish. I mention observing religious festivals; I use lots of Yiddish and occasionally Hebrew phrases; I have a hamsa and a Star of David badge on my backpack, as well as on the jacket I was wearing that night (I also have a Lenin badge on the jacket). The idea that these three white English men entered this conversation about WWII with a Jew and then were surprised (it was very clear they were all surprised and uncomfortable) at the mention of genocide is baffling to me, but I think all too common. I didn’t even mention the Shoah (although I think I did eventually say something like ‘I don’t think invading other countries is the greatest evil for which Nazi Germany is remembered’).

At some point later in the conversation I said something like ‘for all the negative views abounding on the Soviet Union, speaking as a queer Jew, I think I’d have preferred to live there than in Britain at the time’, to which my colleague with the history degree replied ‘well I obviously can’t speak to that’. It was very clear that he meant he can’t speak to Jewish and I guess queer identity. Now this is not the first time I’ve encountered this, but I think it’s an important phenomenon to observe. I once said to another colleague ‘well, there are lots of people in this country who want me dead because I’m Jewish or nonbinary’, and she said ‘well I can’t even imagine what that’s like’.

What I want to rhetorically ask is: why can’t you imagine it? Why do you imagine you’re safe from these same people? First they came for the communists, then they came for the Jews, then they came for that guy who wrote the poem! Eventually they’ll come for you too, when they drum up some new group to hate and mobilise against. If you can’t imagine what it’s like for fascists to want you dead, maybe you should try?

104 notes

·

View notes

Text

SHANGHAI — Over the past generation, China’s most important relationships were with the more developed world, the one that used to be called the “first world.” Mao Zedong proclaimed China to be the leader of a “third” (non-aligned) world back in the 1970s, and the term later came to be a byword for deprivation. The notion of China as a developing country continues to this day, even as it has become a superpower; as the tech analyst Dan Wang has joked, China will always remain developing — once you’re developed, you’re done.

Fueled by exports to the first world, China became something different — something not of any of the three worlds. We’re still trying to figure out what that new China is and how it now relates to the world of deprivation — what is now called the Global South, where the majority of human beings alive today reside. But amid that uncertainty, Chinese exports to the Global South now exceed those to the Global North considerably — and they’re growing.

The International Monetary Fund expects Asian countries to account for 70% of growth globally this year. China must “shape a new international system that is conducive to hedging against the negative impacts of the West’s decoupling,” the scholar and former People’s Liberation Army theorist Cheng Yawen wrote recently. That plan starts with Southeast Asia and extends throughout the Global South, a terrain that many Chinese intellectuals see as being on their side in the widening divide between the West and the rest.

“The idea is that what China is today, fast-growing countries from Bangladesh to Brazil could be tomorrow.”

China isn’t exporting plastic trinkets to these places but rather the infrastructure for telecommunications, transportation and digitally driven “smart cities.” In other words, China is selling the developmental model that raised its people out of obscurity and poverty to developed global superpower status in a few short decades to countries with people who have decided that they want that too.

The world China is reorienting itself to is a world that, in many respects, looks like China did a generation ago. On offer are the basics of development — education, health care, clean drinking water, housing. But also more than that — technology, communication and transportation.

Back in April, on the eve of a trip to China, Brazilian President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva sat down for an interview with Reuters. “I am going to invite Xi Jinping to come to Brazil,” he said, “to get to know Brazil, to show him the projects that we have of interest for Chinese investment. … What we want is for the Chinese to make investments to generate new jobs and generate new productive assets in Brazil.” After Lula and Xi had met, the Brazilian finance minister proclaimed that “President Lula wants a policy of reindustrialization. This visit starts a new challenge for Brazil: bringing direct investments from China.” Three months later, the battery and electric vehicle giant BYD announced a $624 million investment to build a factory in Brazil, its first outside Asia.

Across the Global South, fast-growing countries from Bangladesh to Brazil can send raw materials to China and get technological devices in exchange. The idea is that what China is today, they could be tomorrow.

At The Kunming Institute of Botany

In April, I went to Kunming to visit one of China’s most important environmental conservation outfits — the Kunming Institute of Botany. Like the British Museum’s antiquities collected from everywhere that the empire once extended, the seed bank here (China’s largest) aspires to acquire thousands of samples of various plant species and become a regional hub for future biotech research.

From the Kunming train station, you can travel by Chinese high-speed rail to Vientiane; if all goes according to plan, the line will soon be extended to Bangkok. At Yunnan University across town, the economics department researches “frontier economics” with an eye to Southeast Asian neighboring states, while the international relations department focuses on trade pacts within the region and a community of anthropologists tries to figure out what it all means.

Kunming is a bland, air-conditioned provincial capital in a province of startling ethnic and geographic diversity. In this respect, it is a template for Chinese development around Southeast Asia. Perhaps in the future, Dhaka, Naypyidaw and Phnom Penh will provide the reassuring boredom of a Kunming afternoon.

Imagine you work at the consulate of Bangladesh in Kunming. Why are you in Kunming? What does Kunming have that you want?

The Bengali poet Rabindranath Tagore lyrically described Asia’s communities as organic and spiritual in contrast with the materialism of the West. As Tagore spoke of the liberatory powers of art, his Chinese listeners scoffed. The Chinese poet Wen Yiduo, who moved to Kunming during World War II and is commemorated with a statue at Yunnan Normal University in Kunming, wrote that Tagore’s work had no form: “The greatest fault in Tagore’s art is that he has no grasp of reality. Literature is an expression of life and even metaphysical poetry cannot be an exception. Everyday life is the basic stuff of literature, and the experiences of life are universal things.”

“Xi Jinping famously said that China doesn’t export revolution. But what else do you call train lines, 5G connectivity and scientific research centers appearing in places that previously had none of these things?”

If Tagore’s Bengali modernism championed a spiritual lens for life rather than the materiality of Western colonialists, Chinese modernists decided that only by being more materialist than Westerners could they regain sovereignty. Mao had said rural deprivation was “一穷二白” — poor and empty; Wen accused Tagore’s poetry of being formless. Hegel sneered that Asia had no history, since the same phenomena simply repeated themselves again and again — the cycle of planting and harvest in agricultural societies.

For modernists, such societies were devoid of historical meaning in addition to being poor and readily exploited. The amorphous realm of the spirit was for losers, the Chinese May 4th generation decided. Railroads, shipyards and electrification offered salvation.

Today, as Chinese roads, telecoms and entrepreneurs transform Bangladesh and its peers in the developing world, you could say that the argument has been won by the Chinese. Chinese infrastructure creates a new sort of blank generic urban template, one seen first in Shenzhen, then in Kunming and lately in Vientiane, Dhaka or Indonesian mining towns.

The sleepy backwaters of Southeast Asia have seen previous waves of Chinese pollinators. Low Lan Pak, a tin miner from Guangdong, established a revolutionary state in Indonesia in the 18th century. Li Mi, a Kuomintang general, set up an independent republic in what is now northern Myanmar after World War II.

New sorts of communities might walk on the new roads and make calls on the new telecom networks and find work in the new factories that have been built with Chinese technology and funded by Chinese money across Southeast Asia. One Bangladeshi investor told me that his government prefers direct investment to aid — aid organizations are incentivized to portray Bangladesh as eternally poor, while Huawei and Chinese investors play up the country’s development prospects and bright future. In the latter, Bangladeshis tend to agree.

“Is China a place, or is it a recipe for social structure that can be implemented generically anywhere?”

The majority of human beings alive today live in a world of not enough: not enough food; not enough security; not enough housing, education, health care; not enough rights for women; not enough potable water. They are desperate to get out of there, as China has. They might or might not like Chinese government policies or the transactional attitudes of Chinese entrepreneurs, but such concerns are usually of little importance to countries struggling to bootstrap their way out of poverty.

The first world tends to see the third as a rebuke and a threat. Most Southeast Asian countries have historically borne abuse in relationship to these American fears. Most American companies don’t tend to see Pakistan or Bangladesh or Sumatra as places they’d like invest money in. But opportunity beckons for Chinese companies seeking markets outside their nation’s borders and finding countries with rapidly growing populations and GDPs. Imagine a Huawei engineer in a rural Bangladeshi village, eating a bad lunch with the mayor, surrounded by rice paddies — he might remember the Hunan of his childhood.

Xi Jinping famously said that China doesn’t export revolution. But what else do you call train lines, 5G connectivity and scientific research centers appearing in places that previously had none of these things?

Across the vastness of a world that most first-worlders would not wish to visit, Chinese entrepreneurs are setting up electric vehicle and battery companies, installing broadband and building trains. The world that is looming into view on Huawei’s 2022 business report is one in which Asia is the center of the global economy and China sits at its core, the hub from which sophisticated and carbon-neutral technologies are distributed. Down the spokes the other way come soybeans, jute and nickel. Lenin’s term for this kind of political economy was imperialism.

If the Chinese economy is the set of processes that created and create China, then its exports today are China — technologies, knowledge, communication networks, forms of organization. But is China a place, or is it a recipe for social structure that can be implemented generically anywhere?

Huawei Station

Huawei’s connections to the Chinese Communist Party remain unclear, but there is certainly a case of elective affinities. Huawei’s descriptions of selfless, nameless engineers working to bring telecoms to the countryside of Bangladesh is reminiscent of Party propaganda and “socialist realist” art. As a young man, Ren Zhengfei, Huawei’s CEO, spent time in the Chongqing of Mao’s “third front,” where resources were redistributed to develop new urban centers; the logic of starting in rural areas and working your way to the center, using infrastructure to rappel your way up, is embedded within the Maoist ideas that he studied at the time. Today, it underpins Huawei’s business development throughout the Global South.

I stopped by the Huawei Analyst Summit in April to see if I could connect the company’s history to today. The Bildungsroman of Huawei’s corporate development includes battles against entrenched state-owned monopolies in the more developed parts of the country. The story goes that Huawei couldn’t make inroads in established markets against state-owned competitors, so got started in benighted rural areas where the original leaders had to brainstorm what to do if rats ate the cables or rainstorms swept power stations away; this story is mobilized today to explain their work overseas.

Perhaps at one point, Huawei could have been just another boring corporation selling plastic objects to consumers across the developed world, but that time ended definitively with Western sanctions in 2019, effectively banning the company from doing business in the U.S. The sanctions didn’t kill Huawei, obviously, and they may have made it stronger. They certainly made it weirder, more militant and more focused on the markets largely scorned by the Ericssons and Nokias of the world. Huawei retrenched to its core strength: providing rural and remote areas with access to connectivity across difficult terrain with the intention that these networks will fuel telehealth and digital education and rapidly scale the heights of development.

Huawei used to do this with dial-up modems in China, but now it is building 5G networks across the Global South. The Chinese government is supportive of these efforts; Huawei’s HQ has a subway station named for the company, and in 2022 the government offered the company massive subsidies.

“For many countries in the Global South, the model of development exemplified by Shenzhen seems plausible and attainable.”

For years, the notion of an ideological struggle between the U.S. and China was dismissed; China is capitalist, they said. Just look at the Louis Vuitton bags. This misses a central truth of the economy of the 21st century. The means of production now are internet servers, which are used for digital communication, for data farms and blockchain, for AI and telehealth. Capitalists control the means of production in the United States, but the state controls the means of production in China. In the U.S. and countries that implicitly accept its tech dominance, private businesspeople dictate the rules of the internet, often to the displeasure of elected politicians who accuse them of rigging elections, fueling inequality or colluding with communists. The difference with China, in which the state has maintained clear regulatory control over the internet since the early days, couldn’t be clearer.

The capitalist system pursues frontier technologies and profits, but companies like Huawei pursue scalability to the forgotten people of the world. For better or worse, it’s San Francisco or Shenzhen. For many countries in the Global South, the model of development exemplified by Shenzhen seems more plausible and attainable. Nobody thinks they can replicate Silicon Valley, but many seem to think they can replicate Chinese infrastructure-driven middle-class consumerism.

As Deng Xiaoping said, it doesn’t matter if it is a black cat or a white cat, just get a cat that catches mice. Today, leaders of Global South countries complain about the ideological components of American aid; they just want a cat that can catch their mice. Chinese investment is blank — no ideological strings attached. But this begs the question: If China builds the future of Bangladesh, Indonesia, Pakistan and Laos, then is their future Chinese?

Telecommunications and 5G is at the heart of this because connectivity can enable rapid upgrades in health and education via digital technology such as telehealth, whereby people in remote villages are able to consult with doctors and hospitals in more developed regions. For example, Huawei has retrofitted Thailand’s biggest and oldest hospital with 5G to communicate with villages in Thailand’s poor interior — the sort of places a new Chinese high-speed train line could potentially provide links with the outside world — offering Thai villagers without the ability to travel into town the opportunity to get medical treatments and consultations remotely.

The IMF has proposed that Asia’s developing belt “should prioritize reforms that boost innovation and digitalization while accelerating the green energy transition,” but there is little detail about who exactly ought to be doing all of that building and connecting. In many cases and places, it’s Chinese infrastructure and companies like Huawei that are enabling Thai villagers to live as they do in Guizhou.

Chinese Style Modernization?

The People’s Republic of China is “infinitely stronger than the Soviet Union ever was,” the U.S. ambassador to China, Nicholas Burns, told Politico in April. This prowess “is based on the extraordinary strength of the Chinese economy — its science and technology research base, its innovative capacity and its ambitions in the Indo-Pacific to be the dominant power in the future.” This increasingly feels more like the official position of the U.S. government than a random comment.

Ten years ago, Xi Jinping proposed the notion of a “maritime Silk Road” to the Indonesian Parliament. Today, Indonesia is building an entirely new capital — Nusantara — for which China is providing “smart city” technologies. Indonesia has a complex history with ethnic Chinese merchants, who played an intermediary role between Indigenous people and Western colonists in the 19th century and have been seen as CCP proxies for the past half century or so. But the country is nevertheless moving decisively towards China’s pole, adopting Chinese developmental rhythms and using Chinese technology and infrastructure to unlock the door to the future. “The internet, roads, ports, logistics — most of these were built by Chinese companies,” observed a local scholar.

The months since the 20th Communist Party Congress have seen the introduction of what Chinese diplomats call “Chinese-style modernization,” a clunky slogan that can evoke the worst and most boring agitprop of the Soviet era. But the concept just means exporting Chinese bones to other social bodies around the world.

If every apartment decorated with IKEA furniture looks the same, prepare for every city in booming Asia to start looking like Shenzhen. If you like clean streets, bullet trains, public safety and fast Wi-Fi, this may not be a bad thing.

Chinese trade with Southeast Asia is roughly double that between China and the U.S., and Chinese technology infrastructure is spreading out from places like the “Huawei University” at Indonesia’s Bandung Institute of Technology, which plans to train 100,000 telecom engineers in the next five years. We’re about to see a generation of “barefoot doctors” throughout Southeast Asia traveling by moped across landscapes of underdevelopment connected to hubs of medical data built by Chinese companies with Chinese technology.

In 1955, the year of the Bandung Conference in Indonesia, the non-aligned world was almost entirely poor, cut off from the means of production in a world where nearly 50% of GDP globally was in the U.S. Today, the logic of that landmark conference is alive today in Chinese informal networks across the Global South, with the key difference that China can now offer these countries the possibility of building their own future without talking to anyone from the Global North.

Welcome to the Sinosphere, where the tides of Chinese development lap over its borders into the remote forests of tropical Asia, and beyond.

60 notes

·

View notes

Text

Credit and Blame

There's an interesting philosophical question that is touched upon in Kim Possible, more specifically in S02E04: The Ron Factor and it has to do with how we award credit or blame based on perceived skill. The show is aware that, on its face, Kim often seems to be succeeding in spite of Ron's contributions. So, we get this episode to subvert that expectation.

Both Kim and Ron have good intentions in trying to save the world. Kim attributes her aptitude to her excellent genetics while Global Justice is operating under the belief that Ron's intangibles just sort of "cosmically" bring them success. We know that there's truth to both theories because Sitch in Time confirms that the two need to be a team to work (if you take Shego's word for it anyway).

Thus, I have arrived at the point. I want to push back on the idea that Ron's contributions to the fight against evil aren't as valuable as Kim's. I get the reasoning behind the thought -- Mr. Dumb Skill often seems to solve problems without even fully being aware that they exist. The whole opening of Rappin' Drakken is a good illustration of this, where Ron both accidentally finds Drakken's lair and breaks his drone.

That doesn't change the fact that he's there; he's trying. It certainly didn't appear like Kim was going to stop that thing before it did whatever it was going to do in the upper atmosphere. Neither method of world saving in more inherently valuable than the other if they both get the job done. Kim picked her genetics just as much as Ron picked how chaos theory chooses to apply his intangibles to the universe.

Alas, the point is moot. The episode returns to the status quo notion that your world-savior is mostly Kim with a little help from Ron. No need to reassess when you can just give him monkey superpowers later.

54 notes

·

View notes

Text

Mutually Assured Destruction (Yandere! America vs. Yandere! China x Microstate! Reader)

Warnings: Yandere character, yandere behavior, manipulation, implied kidnapping and choking.

Anonymous Request: I want to see some Yandere struggle. Can I get Yandere USA and Yandere China both falling for a Microstate?

.

.

.

Microstates weren’t supposed to be all that important in the grand scheme of things. Sure, being a Microstate, or any sort of state at all, was enough to warrant some sort of recognition, but that was mostly relegated to the citizens of said state. For the most part, Microstates were left to their own devices. Often, they had to rely on the economic and political structure of Nations that were far more powerful than them to keep their citizens safe and to survive into the next century. The tricky thing about relying on other Nations was that Microstates were at their mercy, no matter how much they liked to tell themselves that they could be as self-sufficient and be as formidable as any other Nation.

In short, Microstates were usually held at the bottom of the food chain due to their lack of importance while global superpowers were the apex predators because their actions could impact the global environment for years to come.

As a Microstate, you weren’t supposed to garner the attention of Nations who held a higher status than you. Even some of your citizens, few as they were, didn’t seem to recognize you. Despite that, however, you were content to live life as quietly as possible. It was inevitable that you would soon one day disappear, either by getting dissolved by one of your powerful neighbors or being inevitably forgotten by your people. It was with that way of thinking, that you found yourself quite dumbfounded by a few events that followed due to a series of ill timed positions.

One, you found yourself invited to a meeting that included all the Microstates—courtesy of Sealand and Molossia.

Two, you were tasked with retrieving some snacks from a popular cafe that Wy had researched when everyone began to complain that they were hungry.

Three, you happened to bump into two of the world’s most powerful global superpowers.

Normally, this wouldn’t have fazed you. You have seen the G8 in action before, but not in such close proximity. As China made a jab about America and his policies concerning foreign relations, you tried to shrink into yourself, appearing much smaller than you were as you browsed through the cafe’s dessert options that were mounted on the wall behind the cashier. As you pondered the pros and cons of getting everyone the same pastry for a discount or getting an assortment, you were halted in your thoughts when you became aware that the fighting had become somewhat louder.

And that they were behind you.

Not wanting to attract too much attention, you tried to subtly signal to the cashier that you wanted an assortment that you could take back to the meeting. As the employee rifled through a stack of flat cardboard boxes to assemble, the bickering duo finally took notice of you.

Again, you were not a powerful Nation. You weren’t powerful enough to land yourself on the radar of your closest neighbors, much less gain the attention of America and China. Yet, just as you were about to fish out enough money to pay for the goods, you felt a hand grab your wrist and a voice in your ear. It was warm, husky, and with an undertone of dominance hiding beneath a veneer of kindness.

“Hi, there! You’re one of the Micronations gathered today, right?” At your curious nod, America nodded confidently. “Here, let me help pay for your food.”

At your confused expression, he elaborated, almost a little too smugly, “It’s not every day that I get to hang out with Microstates like you. Aren’t I generous for noticing you?”

Before you could say anything, China piped up, “Generosity does not always mean you can flaunt your money around, America.” He fumed a little, his dark eyes fiery with simmering anger. When he turned to you, though, he had softened and nodded to you in acknowledgement. “Don’t ally yourself with this one, Microstate, he’ll just use you to get more money for himself because he still owes me.”

“Whatever you say, old man.”

“I’ll be sure to take you advice, Mr. China.” You bowed your head a little before smiling at the blond global superpower. “But don’t worry, Mr. America, I already have this covered.”

And after that, you left.

Were this any other situation, you would have banished that interaction into the furthest corners of your mind. You were a small speck on the map and they commanded the respect and attention of the world. Yet, you began to feel that something had shifted shortly after the meeting with your fellow Micronations.

For instance, America would follow you around everywhere. He had claimed that you were fun, but that didn’t make sense. You had only known him through his reputation as a larger Nation and that brief conversation at the cafe. How could he have known that you were fun from how brief those interactions were? Much to your displeasure, America waved away your concerns and said that he just liked making new friends. That wasn’t a problem, was it?

Reluctant, but not wanting to make things harder for yourself, you allowed him to hang around. At first, his presence was somewhat enjoyable. He would crack jokes, take you out to fancy restaurants after meetings, and get lost with you in foreign capitals.

What made you uneasy was that this man never let you say no. He never wanted you to pay for the nice things he bought you. He never wanted you to go back and see your friends, stating that you would see them again anyway. You’re his new friend and it only makes sense that you spend more time with him!

So you had no choice, but to endure the American’s overbearing advances.

And then, there was China.

Whereas America was more overt in his friendship with you and made you feel uneasy, it was China who terrified you.

Somehow, the Chinese Nation had found out your email and your personal phone number. You reasoned that maybe he had taken your contact information from a public directory or had asked one of your close friends, but upon further investigation, you found out that none of your close friends or any of the other Micronations had interacted with the Eastern global superpower.

It was benign, though, so you let it pass.

With China, you would never see his face. Whenever possible, China would pepper your phone with seemingly curious texts. He would wish you good mornings, inquiries into your day, and what your h to ought were concerning politics and philosophy. You thought about asking why he was so interested in you, but since you were usually hanging out with America and didn’t want to cause more controversy between these two men, you refrained.

Instead, you replied to China.

You will not lie; talking to China was actually relaxing. While America was overbearing and his temper fluctuated like the ups and downs of a roller coaster, China’s long winded and consistently well worded paragraphs made you laugh. His refusal to admit that he was too old for technology made this seemingly ancient Nation somewhat adorable and to a certain extent, relatable.

You considered China to be a penpal.

On the other hand, America was a nuisance who had no idea what personal boundaries were.

One day, China messaged you. You waited a second to make sure that American wasn’t paying attention to you, and then you sent an enthusiastic reply. Just as quick as you (which was surprising given his age), China suggested that you attend a dinner with him. Apparently, he wanted to get you know better and he was feeling the effects of stress and the boredom of attending too many meetings.

Without thinking about it, you agreed.

The instant you did so, you saw the shadow of someone standing so close to behind you, a warm breath caressing the back of your neck.

“Who were you talking to right now?”

You turned around and found yourself face to face with America. Like many other Nations, you were aware of the raw power that America often hid behind a childish complexion and lackadaisical demeanor. However, it was at that moment that you became aware of how domineering and terrifying America could be if you let him near enough.

And you were stupid enough to turn your back on him.

Never a good move.

His cold blue eyes stared you down, icy fire roaring to life as he advanced upon you. Backing away was your only way out, but before you could make a run for it and ask for help, one of his hands reached out and too you by the shoulder.

Another thing you knew about America from secondhand retellings, but had never experienced until now: he was freakishly strong.

“I asked you a question.” His knuckles whitened as his grip tightened. “Answer me.”

“C-China!”

“So the old man wants to play, huh? Okay then, let’s play..” His other hand crawled up the side of your arm before slithering toward your neck. For a second, it almost felt like a lover’s caress. Too soon, though, he began squeezing you and didn’t stop despite your frantic protests.

“Don’t worry, little Microstate, I’ll take good care of you.”

Dimly, you could hear the light buzzing from your phone as China continued to message you the address and time for your scheduled rendezvous.

.

.

.

DISCLAIMER: I do not condone yandere behavior outside of fictional settings. Please don’t mistake the actions of fictional characters displayed in works of fiction to be considered harmless in real life.

If you want to donate a Ko-Fi, feel free https://ko-fi.com/devintrinidad.

HETALIA AXIS POWERS/WORLD SERIES MASTERLIST

#hetalia#hetalia axis powers#hetalia world series#hws#aph#hetalia china#hetalia america#aph china#hws china#aph america#hws america#yandere hetalia#yandere aph#yandere hws#yandere china#yandere america#yandere x reader#yandere#yandere character#yandere behavior#darestones#devintrinidad

133 notes

·

View notes

Text

"Today’s diplomatic complicity in the catastrophic human rights and humanitarian crisis in Gaza is the culmination of years of erosion of the international rule of law and global human rights system. Such disintegration began in earnest after 9/11, when the United States embarked on its “war on terror,” a campaign that normalized the idea that everything is permissible in the pursuit of “terrorists.” To prosecute its war in Gaza, Israel borrows ethos, strategy, and tactics from that framework, doing so with the support of the United States.

It is as if the grave moral lessons of the Holocaust, of World War II, have been all but forgotten, and with them, the very core of the decades-old “Never Again” principle: its absolute universality, the notion that it protects us all or none of us. This disintegration, so apparent in the destruction of Gaza and the West’s response to it, signals the end of the rules-based order and the start of a new era.

...

A critic of this system might argue that states have only ever paid lip service to universality. The twentieth century abounds with examples of failures to uphold the equal dignity of all: the violence used against those advocating for decolonization, the Vietnam War, the genocides in Cambodia and Rwanda, the wars that followed the breakup of Yugoslavia, and many more. These events all testify to an international system rooted more in systemic inequality and discrimination than in universality. With good reason, one could contend that universality was never applied to Palestinians, who, as the Palestinian American scholar Edward Said expressed it, have been, instead, since 1948, “the victims of the victims, the refugees of the refugees.”

...

Within days of the ICJ ruling and its calls for provisional measures to prevent genocide in Gaza, the United States and a number of other Western governments canceled funding to the UN Relief and Works Agency, which provides a lifeline to people in Gaza. That decision does not just ignore the evident risks of genocide; it serves to amplify and accelerate them. The United States’ superpower status and its influence over Israel means Washington is uniquely positioned to change the reality on the ground in Gaza. More than any other country, the United States can prevent its close ally from continuing to commit atrocities. But thus far, it has chosen not to.

This pattern of conduct comes at a huge cost. As one G-7 diplomat has put it, “We have definitely lost the battle in the Global South. All the work we have done with the Global South (over Ukraine) has been lost. ... Forget about rules, forget about world order. They won’t ever listen to us again.”

5 notes

·

View notes

Text

wip intro: Shattered Earth

On an alternate Earth full of strange and bizarre horrors, nothing is as it seems. An enemy might be a friend and that stranger with amnesia might be someone you knew all along...

taglist: @impaledlotus @thelittlestspider

The current date is February 8th 2005; a not so distant past split off from our reality, where the effects of an anomalous comet, superpowered beings, a brief nuclear exchange, a supervolcano eruption, and an alien invasion have the world in a constant state of uncertainty that its only now starting to adjust to. The entire American midwest is a desolate nuclear wasteland. Europe was annihilated and is now completely abandoned. Corporations control every aspect of people’s lives. Global weather systems have been destroyed and the aftermath has left earth in a new ice age. Entire continents have been infected with invasive, man-eating alien wildlife. Humanity is still in the process of recovering from these events, with the help of some not-so-truly empathetic Martian peacekeepers.

Now is a time of monsters.

So what is SE truly about? SE is, ultimately, a sci-fi fantasy, dark comedy, horror action story about killing the monsters. More importantly however, SE is a story about two teenagers having to grow up way too fast in a world that stubbornly refuses to end, in order to survive everything it throws at them.

Status: Almost entirely planned (Arc 1 is at least); Outlining, scripting

POV: OmniscientTM. we have 80+ characters in this story babaaaay

Format: I’m planning for SE to be a webcomic, so I’ll mostly be posting scripts, sketches, and from time to time some practice comic pages :3

Tropes / Vibes / Themes: friendship, love, queer youth, eugenics, found family, crime lordism/gang warfare, intersolar espionage, weird space magic, loss of innocence when forced to grow up, trauma and healing from it, the human condition, devotion that corrupts, politics and the wasteland it creates, extreme dystopian levels of capitalism, feeling valid in reasons to hate and how first impressions are often times misleading, learning to be selfish...im sure theres more haha vv’

Content Warnings: Offensive/Derogatory/Explicit Language/Slurs**, Explicit Violence/Gore/Body Horror, Nudity, Mature Sexual Themes/Discussions, Drug Use/Abuse, Emotional Mental and Physical Abuse/Manipulation, In*est Mention, Suicide Related Topics, Self Harm, Mass Death/Corpses, Genocide, etc

And now onto our two protagonists :3

NAME: Desmond Oswald Arkady

DOB: November 30th, 1991; 14 years of age

HISTORY: Son of rancher Sloane Arkady and medical nurse Ed Arkady, and unknowing grandnephew of the famous superscientist Lupe Altena. Has two older siblings and one younger sister. Throughout grade school Desmond was noted for having poor social skills and having a severe temper; he was bullied and very much alone during this time. His mother was emotionally and physically absent while his father became emotionally and verbally abusive as he grew older. Eventually his parents split, Ed taking Desmond and his brother Jerome, with Sloane (under legal definition) ‘kidnapping’ their younger sister Zuri. Oldest sibling “Happy”’s whereabouts are unknown. In 2003 abnormal brain wave activity was reported, benign; his temper somewhat subsided. The remnants of the family moved to the NEC in late 2004.

Desmond’s above-average school grades have currently led to him attending the Promethean School of Science under the tutelage of one infamous Dr. Maya Fontaine. He seems to have an interest in all things biomedical and mechanical.

OCCUPATION: Officially listed as a part-time bowling alley attendant at Crimson Head Lanes. Unofficially: errand boy and lookout for the criminal body behind the bowling alley.

ORIGIN: A small black earth town in former Kentucky known only as “Carbonville” that no longer exists.

Last Known Whereabouts: Lives in NEC, DUSA.

Identifying Characteristics: African-American, mole on left cheekbone, shaved dark brown hair, late bloomer in terms of height at just 5 feet tall, noticeably overweight and stocky. Known to almost constantly fiddle with his hands due to reported hypersensitive dermis and nerve damage stemming from contact with a wildfire some years before.

PSYCH: Annoyingly positive attitude that hides a deep, festering rage. An overbearing people pleaser almost to the point of submission. Desperate for validation and a sense of belonging. Chronically low self-esteem. Extreme levels of anxiety. Is repressing serious anger issues to the point of migraines and blackouts. Possible case of undiagnosed autism. Easy to intimidate and manipulate.

NAME: Francis T. Mueller

DOB: August 1990; 15 years of age

History: One of the many thousands of Chimera children of the Martian King Azelfafage, Francis was raised by her human mother Roxanne Mueller. Her mother being a drug addict and abusive, Francis from an early age found herself doing any odd job she could to simply feed herself, which soon escalated to working for the assassins guild, Antumbra for a short time at the young age of 10, and working as a bodyguard and gunner for various drug dealers up until the age of 12.

At 9 years old she experienced a medical “accident” that resulted in a severe case of dissociative amnesia.

Police records in 2003 indicate that after her release from brief juvenile custody, Francis worked her way up from petty thug to where she is now working for Crimson Head Lanes. Conflicting reports state that Francis was “handed over” to CHL and is working for them unwillingly by use of either force or threat.

Occupation: Officially listed as a bowling alley attendant at Crimson Head Lanes. Unofficially: hitman thought to be employed by CHL owner Carmine Keller, as well as gunner, enforcer, and more recently the bodyguard of fellow coworker Desmond Arkady.

Origin: NEC, DUSA.

Last Known Whereabouts: NEC, DUSA.

Identifying Characteristics: Curly red hair and freckled dark brown skin like all Chimera. Crimson red teeth. Androgynous/masculine facial and body structure, usually mistaken for a male. Magenta eyes on yellow that in a highly unusual case shift to white on black in low-light settings, a possible case of intersexism or a mutation. Identifies as a transgender female. Over 6 feet tall and malnourished for a half-alien child.

Psych: Mentally and emotionally unstable, a possible case of borderline personality disorder and even sociopathy. Possibly suffers from a panic or anxiety disorder as well. A loner, dangerous, known for violent mood swings and outbursts. Suffers from dissociative amnesia, PTSD, and alcoholism.

—

**Unfortunately, in the world this comic’s set in (the world ‘ended’ in the 1960s), people aren’t very accepting or understanding of different sexual orientations. Actually, peeps aren’t very accepting in general. It’s a distrust of foreign cultures and ideas, mostly, mixed with good old fashioned repressed victorian standards and ideals.

The only worse thing worse for your career/life in this universe is to be labelled a stinkin’ commie.

57 notes

·

View notes

Text

Soon come... “King Killmonger: The Golden Jaguar”

Summary: